1 INTRODUCTION

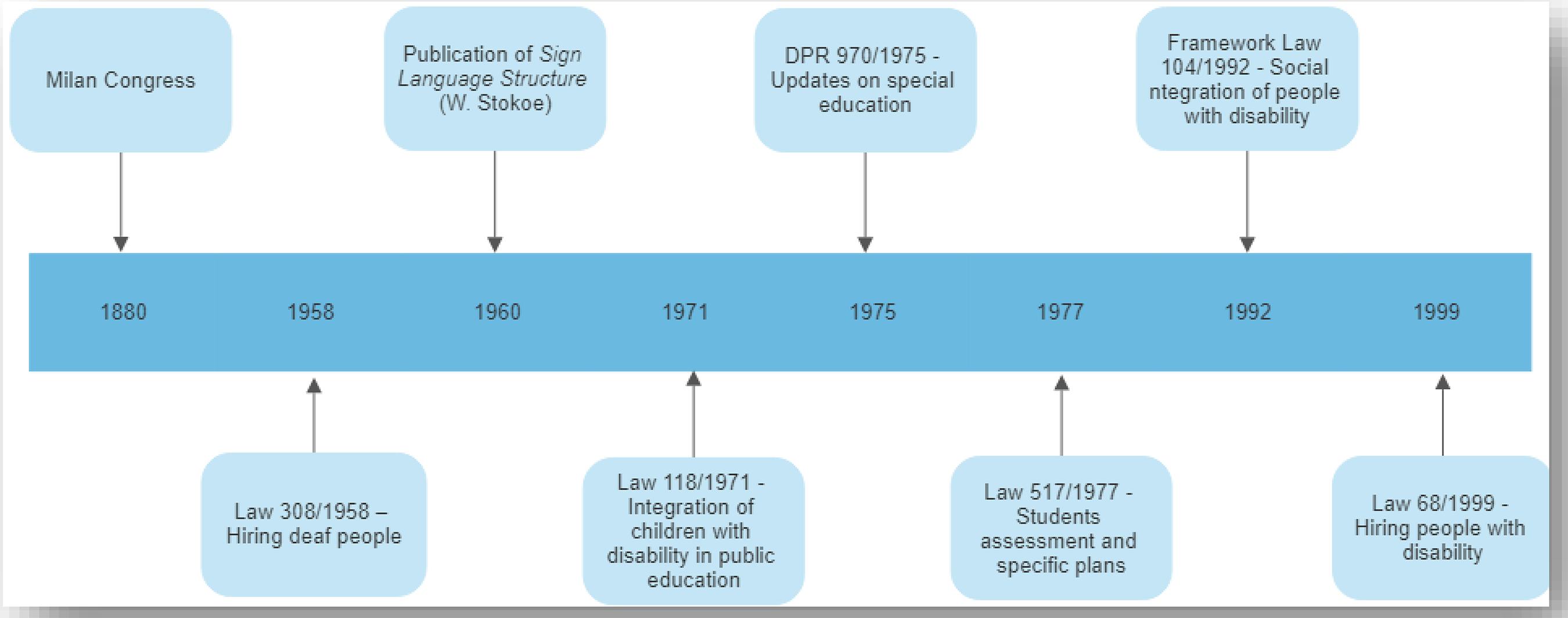

Deaf education in spoken language has changed a lot in the past 60 years (LEESON, 2006; RINALDI, DI MASCIO, et al., 2015). Should we consider the publication of Stokoe’s “Sign language structure” (1993 (1960)) as a turning point in deaf education and in sign language’s linguistic recognition, a timeline can be set on the way deaf people are educated. In Italy, where the Milan Congress has meant a switch from bimodal to oral education in most of the exhisting special schools for the deaf, the return to the use of sign language (SL) in the education of deaf children has been slow and difficult. In 1971, the law n°118 allowed the integration of children with disabilities in public education; all children where equally welcomed, and any specific educational or professional path was designed for any of their peers, not specifically for them. As I will further discuss in §2, it was the beginning of a deep change in the way children with disabilities were perceived and educated, and the baseline for the creation of new professional profiles dedicated to assisting them in their scholastic carreer. These professionals were gradually included in public education and trained to a greater awareness of the peculiarities coming from specific disabilities. Although great attention has been put on the way in which deaf children should be taught and included in the social setting, very little is known about the deaf adults and the way in which they can keep growing, socially and professionally.

According to the World Health Organization webpages on Deafness and hearing loss, “by 2050 nearly 2.5 billion people are projected to have some degree of hearing loss and at least 700 million – one in every ten people - will require hearing rehabilitation” (2021). When focusing on the European Union, the report published for Hear-it AISBL (2019) counts up to 34.4 million adults having a disabling hearing loss (35 dB or greater). As I will discuss in §5, despite of these numbers and of the improvement showed by vocational training since the early 2000s, very little is done to improve a valid methodology for their vocational training.

As research has shown, subtitling contents is not enough to provide efficient access for most deaf people; accessibility, content structures and the educational background of the target needs to be considered (§§3-4).

The goal of this contribution is thus to provide an overview of the educational needs of deaf adults and to draft a methodology for the design of efficient training courses, taking their age and educational background in consideration, as an essential part of the design of the educational content. In my discussion, I will also address the case of foreign deaf learners (§4), who present unique sociolinguistic profiles and learning needs, when compaired to their “local” peers.

2 DEAF EDUCATION IN ITALY, AN OVERVIEW

As already mentioned in De Monte (in press), in the years between 1784 and 1971, special schools for the education of the deaf and hard-of-hearing were the norm for children with deafness, in Italy. Children would attend to private boarding schools, mostly run by religious orders, to learn how to read, write, do math, speak, use their residual hearing and practice craftsmanship, normally tailoring, embroidering, bindery, carpentry, etc. Young deaf adults would exit special education knowing how to read and write, at an elementary level, and how to work in the craftsmanship of their choice. It was considered useful to allow people with disability to learn a profession where they could excel, and self-sustain themselves in their adult lives. They would normally be hired by companies searching for their abilities and rarely change job unless the company would fire them or they’d be hired in any public administration position2.

When the law 118/1971 begun to inform about how to provide public education to children with disabilities, families would gradually choose to enroll their children in schools that would be nearer to their homes. At the time, one of the critical issues was the lack of professional profiles who were trained to treat children with disabilities. Actually, the law informed about the right for children with disabilities to enroll in public education and their right to be assisted by a specialised teacher (Personale ed educatori specializzati) trained by universities and other higher education bodies. However, it is only in 1975 that a presidential decree (Decreto Presidente Repubblica 31 ottobre 1975, n. 970) explains how these specialised teacher can actually access public education. Thus, it is reasonable to suppose that these children were mostly left to the good intentions and capabilities of their teachers up until 1977, when the Italian legislation on the education of children with disabilities was enriched with more details on how to design specific educational plans and how to assess them (law 517/1977).

It is important to note that, despite of the matter being formally under the spotlight since 1971, at the time when things started to clear out for public education (1977) courses training specialized teachers were very few and mostly based on the experience of educators coming from the above-mentioned special schools. In fact, it is only in the early eighties that research on deafness and sign language begins to formalise in Italy (VOLTERRA, ROCCAFORTE, et al., 2019, p. 21-22). In such an experimental phase of the inclusion of deaf children in public education, it is reasonable to expect a very high variability in their preparation, mostly related to the contemporary exhistence of children attending to public schools (not always prepared for them) and children enrolled in special boarding schools for the deaf.

In 1992, the framework law n° 104 (GIACOBINI, 2022), creates a new professional profile trained to assist children with special needs related to communication disabilities: the communication assistant (Assistente all’autonomia e alla comunicazione). The role of this new professional is to support the child during the learning process using a set of strategies to adapt the contents provided by teachers during their classes. Since 1992, main changes have concerned the lenght of compulsory education, now lasting at least 10 years, counting from the enrollment in elementary school and up until the 16th year of age, and the introduction of an educational operator (Operatore Educativo per l’Autonomia e la Comunicazione) to ease the socialization of children with communication disabilities.

Figure 1 summarises the evolution of the laws on special education and work integration for people with disability as discussed in this paragraph.

3 BEING A DEAF ADULT IN ITALY

Given the educational and legislation framework provided in the previous paragraph, it is reasonable to group Italian deaf adults in their working age (16-67 years old) in the following subgroups:

The generation of deaf who were educated in special boarding schools (until 1971-1977), now aged mostly above fifty years. They have learned to use sign language in private communication and to avoid its use in public. Their competence in spoken/written Italian is most likely at an elementary level;

The generation of deaf who attended public schools in the years of the transition from special to public schools (1971 – 1977), now aged between thirty-five and fifty years. Their knowledge of sign language can be scattered and incomplete, given the absence of a context of use in early childhood. Their linguistic skills in the spoken language can also be incomplete, due to the lack or incomplete specialised support while learning at school. Unless they have had the opportunity to catch up their delays in one or the other language, they may suffer of incomplete competence in both Italian and Italian Sign Language.

Deaf adults who attended school after the law 104/1992 has passed and who are now under forty years old. This group of deaf people were exposed to both special teachers and communication assistants and lived through the age of sign language “empowerment”. Therefore, they received more support at school and they are not ashamed to use sign language in public. They may show more confidence when compared to their older peers. Their competence in Italian may vary, but it is normally higher than the previous generations (DE MONTE, 2017). This group can also be sub-divided into a fourth group, characterized by the introduction and diffusion of communication technologies, thus

Deaf adults who are digital natives, thus falling into the broader definition of “millennials” and any following generation who have always had access to communication technologies and the Internet. In the case of the deaf, accessing online communication technologies has marked the end of isolation and the opening of a number of social opportunities as never before. It has also meant an increased possibility to use sign language in online contexts and to use written language in online settings. Thus, their exposure to languages is at the highest available level.

While the above-mentioned “groups” can be selected for their educational background and training to Italian, exposure to Italian sign language (LIS) is normally informal and casual. Only in the case in which a signer decides to become a sign language teacher, will s/he attend formal education to sign language (more in §5).

4 FOREIGN DEAF LEARNERS

Italian schools and universities have experienced an increase in the number of foreign deaf students applying for their courses. Special attention to this group of people was given by the State Institute for the Deaf help desk on deafness (Sportello sulla sordità) since its foundation in 2003 (MARZIALE BENEDETTA, 2009). In the case of public education, the rise is normally justified by an increased number of families of immigrants who happen to have deaf children. In some cases, the migration itself is justified by the disability of the child. In the case of universities, the rise in the level of D/deaf people’s education, natural curiosity and the search for better working positions has led them to travel more and wish to learn more languages. From another standpoint, the growing number of asylum seekers and migrants escaping from difficult situations, such as war or persecution in their own countries3, has brought deaf adults to arrive to Italy in extremely difficult conditions. They often wait a long time for their legal documents and are thus limited in their freedom to engage in activities that could promote their economic and personal growth. Regardless of the circumstances of their arrival, these people have normally had the opportunity to receive special education and to become proficient in at least one spoken language and/or SL.

As reported by the web pages of the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Disability section (2022),

Although the international normative framework has broadly recognized the importance of addressing the needs of persons with disabilities in the fields of human rights and development, it has historically overlooked the subgroups within the disabled people in the context of migration, including migrant workers with disabilities and refugees with disabilities.

The phenomenon is so neglected that World and European reports on migration don’t even consider disability in their data (see data from the European Commission (2022) and the International Organization for Migration report on World Migration (2019)). Therefore, there are very few data on the real numbers regarding the migration of deaf adults. What we know comes from information collected from consultancy offices such as the already mentioned help desk in the State Institute for the Deaf in Rome, or projects specifically dedicated to the education of deaf foreigners, normally conducted in a jeopardized way in different parts of Italy (some examples are reported in (DE MONTE, 2017; BONANNO, DELLIRI, et al., 2013).

When profoundly deaf people arrives to Italy, they normally find that universities and schools are poorly prepared and not always capable of receiving them in an inclusive way. Desk keepers who may have hard time in communicating with deaf people feel even more powerless when facing foreign deaf people. Sign language interpreters are not always ready for interactions in international signs so, in many cases, they refer to the national association of the deaf (Ente Nazionale Sordi) to receive basic information on how to begin their lives in Italy and get access to the basic provisions that are available for them. This is also where they start to socialize, meeting other deaf people from the host country, learning their sign language and where and how to improve their new spoken/written language.

It is interesting to note how most foreign deaf people, if signers, would attempt to learn the local sign language before they attempt to learn the spoken one. Not only does sign language provide a first access to the local deaf culture but also to the interpreting services eventually made available to them by their hosting university. However, formal training of sign language interpreters does not include the interaction with foreign people, who often code-switch between the sign languages of their competence. Sometimes D/deaf people learn the language of the host country thanks to a speech therapist, who help them to learn basic words of the spoken language, perhaps with the support of SL. In other cases, this target group is addressed by non-academic institutions providing lessons of Italian in classes or individually. In other cases, they would try to attend regular second language classes, with the possibilities and the limits offered by their educational background.

The increase in the arrival of foreign deaf people to Italy, mostly as refugees or tourists, has raised the question around the best way to train them to spoken/written Italian. Informal observation on a group of foreign deaf people arriving to Italy has shown that much depend of the level of education of the deaf person, before their arrival. Usually, deaf people with academic training have more strategies to access a second language. As for any other signer, they would try to learn Italian Sign language as a first communication tool. Then, they would use their new skill to attend to classes of Italian, with the support of a sign language interpreter.

As we know from existing researches on the linguistic competences of deaf people, children who are born deaf or become deaf before the third year of age tend to experience serious challenges in the acquisition of the national spoken language, not only in the vocal and hearing rehabilitation (through the use of hearing support), but also in the mastery of written language (see the edited volumes of Marschark and Spencer (MARSCHARK, SPENCER e NATHAN, 2010; MARSCHARK, SPENCER e NATHAN, 2010; LEESON, 2006).Thus, when designing educational solutions for foreign deaf adults, the main goal that should be addressed is second language education.

5 VOCATIONAL TRAINING EXPERIENCES FOR DEAF ADULTS

Years of discussions around the importance of lifelong learning in adult people, mostly motivated by the need to keep up with the speed of technological advancements and the growth of information made available for everyone, justifies the creation of hundreds of vocational training classes in any possible topic. The growth of any online content experienced during the pandemic has pushed this tendency even further, with universities offering online contents together with classroom-based education. As with any other training product, these classes are normally targeted for specific publics. When coming to adult deaf learners, there are only few courses that were expressly designed for deaf learners. Most courses designed for the deaf are promoted by the National Association for the Deaf, and mostly covers vocational training for future sign language teachers (§5.1). Despite of lifelong learning being mentioned in the law 118/1971 (§2), specifically to provide professional training to people with disability and to fight illiteracy and illiteracy returns, there are actually very few courses addressing these topics (§5.2). In other areas, most of the courses keep their structure close to the one designed for hearing learners, adding subtitles for accessibility (§5.3). However, as I will discuss here, this structure is not always successful for training deaf people.

5.1 Vocational training in sign language education

Native deaf signers also see an opportunity of professional carreer in becoming teachers in their native/local sign language. In the case of LIS, candidate teachers would follow training classes mainly based on Metodo Vista, where they would learn how to identify the grammatical aspects of LIS and, most of all, learn and practice how to teach to a hearing audience. The National Association for the Deaf or other Deaf associations of SL teachers cover most of this kind of training, in Italy. In many cases, theoretical teachers in these associations are invited from local research centers on sign language.

In order to access these courses, it is required for candidates to be over 18 years-old, to have a native-level knowledge of LIS and to complete the schooling cycle with an upper secondary degree (that is, having competed the 10 years cycle and the additional 2-3 years required to achieve the full degree - §2). The programs presented by the most famous courses in Italy for LIS teachers’ training - National association of the Deaf (Ente Nazionale Sordi – ENS) and gruppo SILIS, Rome - report a total training time of 275-295 hours and include training in the following topics:

deaf anthropology

history of the Italian deaf community

linguistics of SL

how to teach SL (glottology and sign language education)

observation methodologies and exercises

professional deontology of LIS teachers

leadership in the educational context

Italian-LIS comparison and internship training

Some courses would also add extra hours to train about the use of Sign Writing as an opportunity to write SL. Once they have completed their training and internship, teachers of SL can apply to have their names added to the national record of LIS teachers (Registro Nazionale Docenti_01) and, eventually, train to become specialists in complementary topics (Registro Nazionale Docenti_02) or coordinators of LIS courses (Registro Nazionale Coordinatori). All records are held by the National Association of the Deaf (ENS).

In 2021, the long awaited law recognizing LIS as the language of the deaf community also delegated universities to train interpreters in both LIS and tactile sign language. Consequently, in the moment when universities were formally called to present proposals for training in LIS (April 2022) the scarcity of deaf sign language teachers holding an academic degree and trained to become teachers became evident. This is even more so for sign language training following the CEFR.

In fact, although the evidence of the importance to adequate sign language training to the CEFR became evident already in 2014. At the time, there were already a few attempts to adapt LIS education to the CEFR. One of such attempts was Metodo c’è; developed and presented by Cooperativa Alba in 2010, it also experimented a new way to teach LIS, which was not exclusively classroom-based, as the totality of the courses existing at the time, but gave students the opportunity to excercise their skills at home, through the use of carefully designed CDs, and then discuss their progress in classroom-based lessons with deaf teachers. In the years between 2011 and 2014, the SignLEF4 project, Funded by the European Commission Lifelong Learning Program, was the first to directly address the matter at an European level. Shortly after, in 2012, the activities of the ProSign project, funded by the European Center for Modern Languages (ECML), opened the discussion to a wider perspective, leading, in 2018, to the publication of the Companion Volume to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, in 2018 (2018). ProSign involved many European countries and institutions for the Deaf, thus reaching a larger public for greater application.

Back to the Italian setting, the goal of the SignLEF project was to test CEFR’s suitability as a standard for SL education and to design and produce materials for classroom-based settings. The team working towards this goal consisted of hearing and deaf professionals: the project manager, administration and one researcher were hearing, skilled in SL; the hearing researcher teamed with three deaf researchers and four professional Deaf teachers of SL, with varying degrees of competence. The team was completed with two video and graphic technicians, both Deaf, who occasionally participated in the discussions with their experience in SL. Using an approach inspired by Action Research (LEWIN, 1946), the team would meet weekly for four hours during the lifetime of the project (36 months). During the meetings, notes and short videos were taken to keep track of the project’s development progress. Moreover, training needs were satisfied when appearing through the information exchange among the team members themselves and/or through the organisation of seminars open to SL teachers.

Since the CEFR was largely unknown for its application to SL education, a lot of time in the project was dedicated to training the deaf colleagues to the way it worked for spoken language, so that it would be easier to think about how to use it as a standard for sign language. In this period, the project collaborators also worked in training candidate Deaf teachers about the CEFR and its characteristics. Training while learning more about the CEFR was an excellent way to feed brainstorming and to collect feedback on a possibly high-impact project, which was immediately used within the project. As the ECML ProSign5 project started to produce its outcomes, findings were compared and integrated to the ones of SignLEF in a virtuous cycle of sharing knowledge and methodology.

5.2 Fighting Illiteracy returns

As most researchers and professionals dealing with deafness and deaf education know, profoundly deaf people who have lost their hearing before the third year of age are at risk of developing low level of literacy in the spoken language of their country. Given the importance of a full competence in the local language for inclusion, the topic has become the center of most developmental studies on deafness. Less is known about how deaf people keep their competence in their adult life. What we know is that, when tested, they often show signs of low literacy, illiteracy return or code-switching with sign language (DE MONTE, 2015). Thus, the deaf person will need to actively practice the language, in order not to lose the acquired competence (GROVES, DE MONTE e ORLETTI, 2013).

That of illiteracy returns and general illiteracy has been a topic for discussion already in the seventies. In fact, given the high number of illiterate people in the years following the end of World War two (WW2), their education is mentioned in the law 118/1971, for the “schools of the people” (Scuole Popolari) were supposed to offer specific courses of Italian for illiterate people. Actually, these courses are mainly dedicated to immigrants, while there are no such courses designed for deaf Italians. All we know is about the existence of a few experiences of Italian classes for deaf adults, normally isolated and unrelated from other courses destinated to the deaf.

In 2012, a study published by Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, provided a first overall picture of the state of the art in the literacy competence of the average Italian speaker, in relation to the evolution of public education in Italy since the end of WW2 and based on the results of the OECD Skill Strategy Diagnostic Reports (2012). Surprisingly, in 2012, 98,6% of the Italian population was literate, but almost 30% of the adults aged between 25 and 65 years old would have limits in comprehension, reading and calculation. This phenomenon is defined as “return illiteracy” and it’s defined by the loss of basic skills of reading and writing, due to the lack of practice after school. Thus, the return illiterates forget what they have learned, losing the ability to use spoken or written language to create or understand messages and, more extensively, to communicate with other people and the surrounding world.

In the case of deaf people, illiteracy return could also be accelerated by the lack of exposure to spoken language through hearing, and the difficulties given by reading long and complex texts. In a research conducted in 2015, I noticed how the group of senior writers in posts hosted in online settings were most likely written in broken I talian or with high occurrencies of code mixing, especially on the structure level. The mixing would appear using reparing strategies that are also typical of low literacy Italian writers.

5.3 Refresher courses and online training

Refresher courses refer to those courses that can be offered to deaf people either to train them on specific topics (security and safety on the workplace, GDPR, new technologies) or as professional updates required in their workplace. In many cases, companies do not provide sign language interpreters or subtitling to their deaf workers. Only recently, companies would offer deaf people the possibility to receive a printed copy of the training materials, which, in all cases, is not enough to grant a full accessibility to its contents. Other cases include subtitling contents. Although this is generally considered as an efficient way to provide accessibility to spoken contents, also supported by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines6 (WCAG) it is not the case. Given the difficulties with spoken language as described in §5.2, it is evident how relying only on written text for full accessibility will not always be enough. In many cases, lifelong learning classes designed for the deaf are planned without considering the costs of having an interpreter or, in the best cases, without considering the specific timing and/or needs of deaf adults who are learning (limited visual resources, need to switch from speaking to writing to signing, etc), which also create the ground for limited accessibility.

Recently, the raising interest by private companies towards sign language and other opportunities for inclusion, increased the rate of fundings for projects aimed at training deaf people to specific contents, through sign language. A few example of these kind of projects are the Signed Safety at Work project (SSaW)7 and the Signs for Work Inclusion Gain project (SWING)8. Both projects had the aim to develop a glossary in sign language destinated to train deaf people to specific signs in use on the workplace. While SSaW was focused on the development of a glossary for Health and Safety on the Workplace, to face immediate emergency situations, SWING is focused on isolating words and signs that are specific of workplaces with a high rate of interactions with the public. Although it is interesting how both projects are intended to improve inclusion on the workplace with deaf signers, providing a signed glossary benefits the hearing population, rather than the deaf workers, who may already know how to sign certain things. The real added value of these projects come from the training that hearing people receive when they learn about how to interact with deaf people and perform some basic signs to get their message out to their interlocutor and, in a way, break the ice that often creates when a hearing person meets a deaf one.

In some cases, glossaries and dictionaries produced by these projects were also reported as being useful as tools of reference for people not being able to sign but wanting to create a bridge for communication with their deaf interlocutor. In a case reported in the news, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, a doctor wanting to communicate with a deaf patient used an online signed glossary to help himself in easing the feelings of his patient and work through difficult moments9. Thus, it appears that the end users are hearing people, despite of these projects being designed for deaf inclusion.

A different approach is the one upholding the Free Technology Signs project10, aimed at “developing accessible and bilingual digital resources (in sign and written language) to enable deaf job seekers to learn independently and acquire knowledge of transferable digital skills” (from the project homepage, “about”). In projects like this one, where the consortium counts a good number of deaf associations and professionals and the final goal is the design of signed contents for accessibility, the target is clearly defined, as well as the goal, around the group of deaf population and their improvement.

6 CONCLUSIONS

When addressing lifelong learning in deaf adults, there are a few conditions that must be taken into consideration. As I discussed here, it is easy to confuse the need of senior deaf people with that of younger generations, or to confuse the need of the deaf workers with that of their hearing colleagues. Thus, when designing lifelong learning solutions for the deaf, the target of users should be clearly defined, also considering:

Age of the target group;

Literacy skills in the target, both in spoken and signed languages;

Educational/rehabilitation program followed by the group, not all deaf people sign and orally educated deaf people might have different needs than signers;

local/national educational policies;

When designing the specific product, engaging with the deaf community from the design to the implementation of the project and planning regular communications in sign/plain language, can help to reach out to the deaf population so that they are informed about products that are designed for them and could potentially of their interest. Contents should be highly visual and any text should be simplified to reach that part having literacy problems. Last, but not least, deaf training is best when there’s a peer to train them. This means involving more deaf people into training or other responsibility roles, helping them to gain more confidence and grow, as any professional should do.