Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Práxis Educativa

versão impressa ISSN 1809-4031versão On-line ISSN 1809-4309

Práxis Educativa vol.16 Ponta Grossa 2021 Epub 20-Out-2021

https://doi.org/10.5212/praxeduc.v.16.17204.010

Entrevista - Dossiê Paulo Freire (1921-2021): 100 anos de história e esperança

Interview with Peter McLaren Radical and hopefull discussions about times of brutal conservatism - paths of fight and transformation in the light of Paulo Freire*

*PhD in Education. Adjunct Professor of the Department of Pedagogy and Professor of the Graduate Program in Education at the State University of Ponta Grossa (UEPG), Paraná, Brazil. Coordinator of the Study and Research Group on Education in School and Non-School Spaces (GEPEDUC). E-mail: <lucrispaula@gmail.com>

**Teaching degree in Language and Literature from the State University of Ponta Grossa. She is currently a Master’s student in the Graduate Program in Language Studies, at the State University of Ponta Grossa. The journal Práxis Educativa thanks her for her collaboration. E-mail: >bhiancamoro@hotmail.com>

In a letter written in February 1994, Paulo Freire lovingly referred to the “intellectual kinship” between people who are strangers from the blood point of view, but who reveal similarities in the way of appreciating the facts, understanding them, valuing them. This kinship is described by the wonderful feeling that invades us when we meet a person and we feel that we are connected to them by an old friendship. It is as if the meeting, in person, was a long-awaited reunion, in which the intercommunication takes place easily and the topics covered are apprehended through similar experiences of epistemological approach to them. Great friendships take root and thrive in this “intellectual relationship”, they cross time and resist possible changes. In that letter, Paulo Freire referred to Peter McLaren, an “intellectual relative” who discovered and by whom he was discovered. After all, as Freire (2005) points put, “no one becomes someone’s relative if the other does not recognize the one as a relative” (p. 247).

Freire had already read McLaren before meeting him in person and soon discovered that they belonged to the same intellectual “family”. However, he made clear that this did not mean reducing each other, as the autonomy of both is what marks the true kinship.

When received the invitation to give this interview, Professor Peter McLaren quickly sent an affirmative answer, showing us great interest in discussing Paulo Freire’s legacy in such difficult times for Brazil and the USA. Peter McLaren, one of the main representatives of Critical Pedagogy, was a professor at the University of California (1985-2013) and currently works at the College of Educational Studies, Chapman University. He works as director of the Democratic Project Paulo Freire and International Ambassador in Global Ethics and Social Justice and he is an expert in the following topics: Liberation Theology and Education in Catholic Social Justice, Revolutionary Critical Pedagogy, Philosophy of Education, Sociology of Education, Marxist Theory and Criticism Theory. He is the author and editor of nearly 50 books and his writings have been translated into more than 25 languages. Professor Peter McLaren is a scholar and activist whose educational work seeks to reflect objectives and practices developed by Paulo Freire.

In this interview he tells us about his life and professional trajectory, how he met Paulo Freire and explains his “intellectual kinship” with him, he brings deep discussions about the moment of extreme and violent neoconservatism that we are experiencing and about his Critical Pedagogy. He ends this interview by pointing out paths of resistance that we need to take as educators and researchers to fight oppression, overcome inequalities, democratizing the university space.

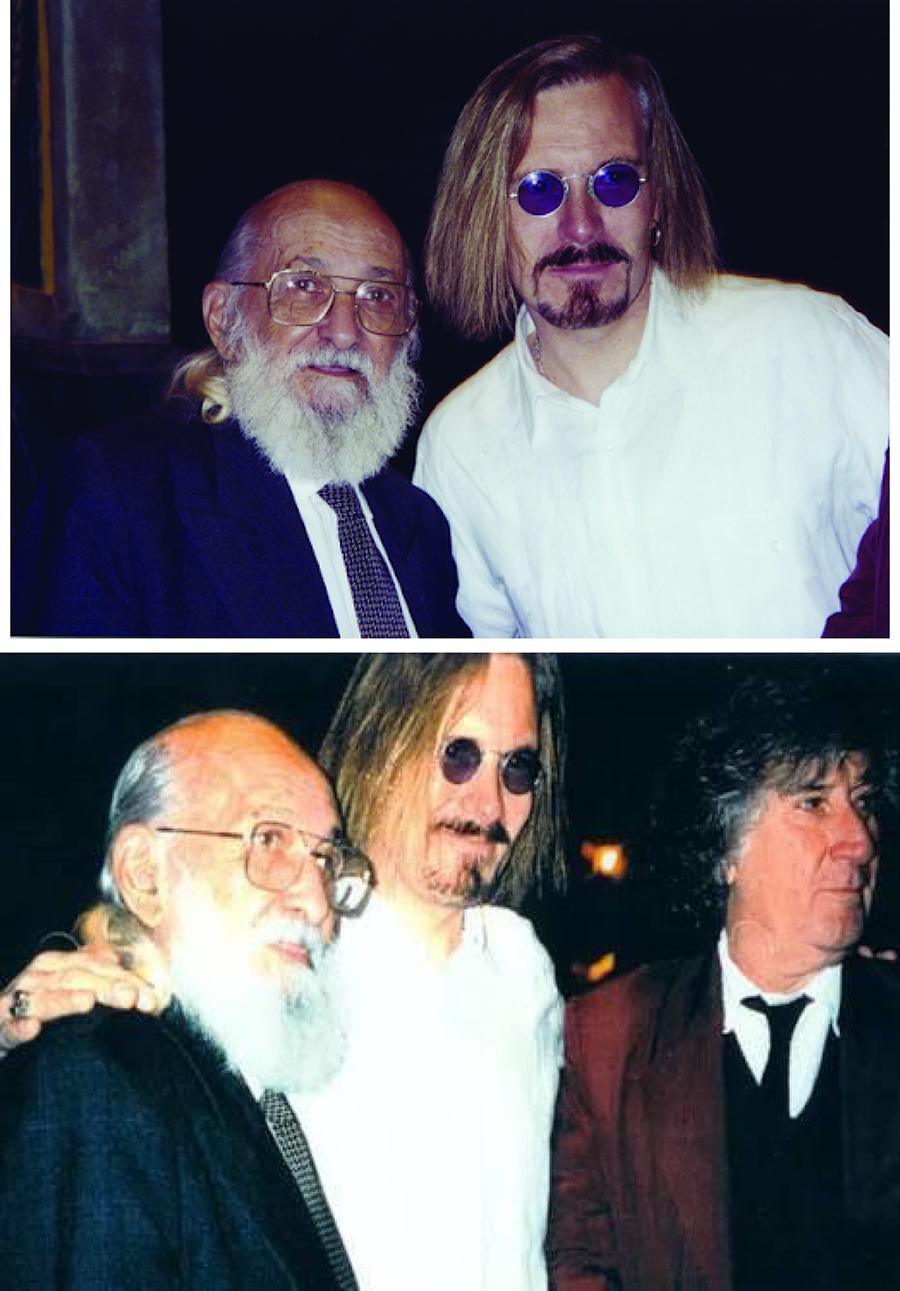

It is an honor for us to count on Professor McLaren (Figures 1 and 2) in this dossier on Paulo Freire’s centenary of birth. We appreciate his special contributions!

Figure 1 Left: Paulo Freire and Peter McLaren at the Rose Theater in Omaha, Nebraska, 1996/Right: Paulo Freire, Peter McLaren and Augusto Boal in dialogue at the Rose Theater in Omaha, Nebraska, 1996 at the Pedagogy of the Oppressed ConferenceSource: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

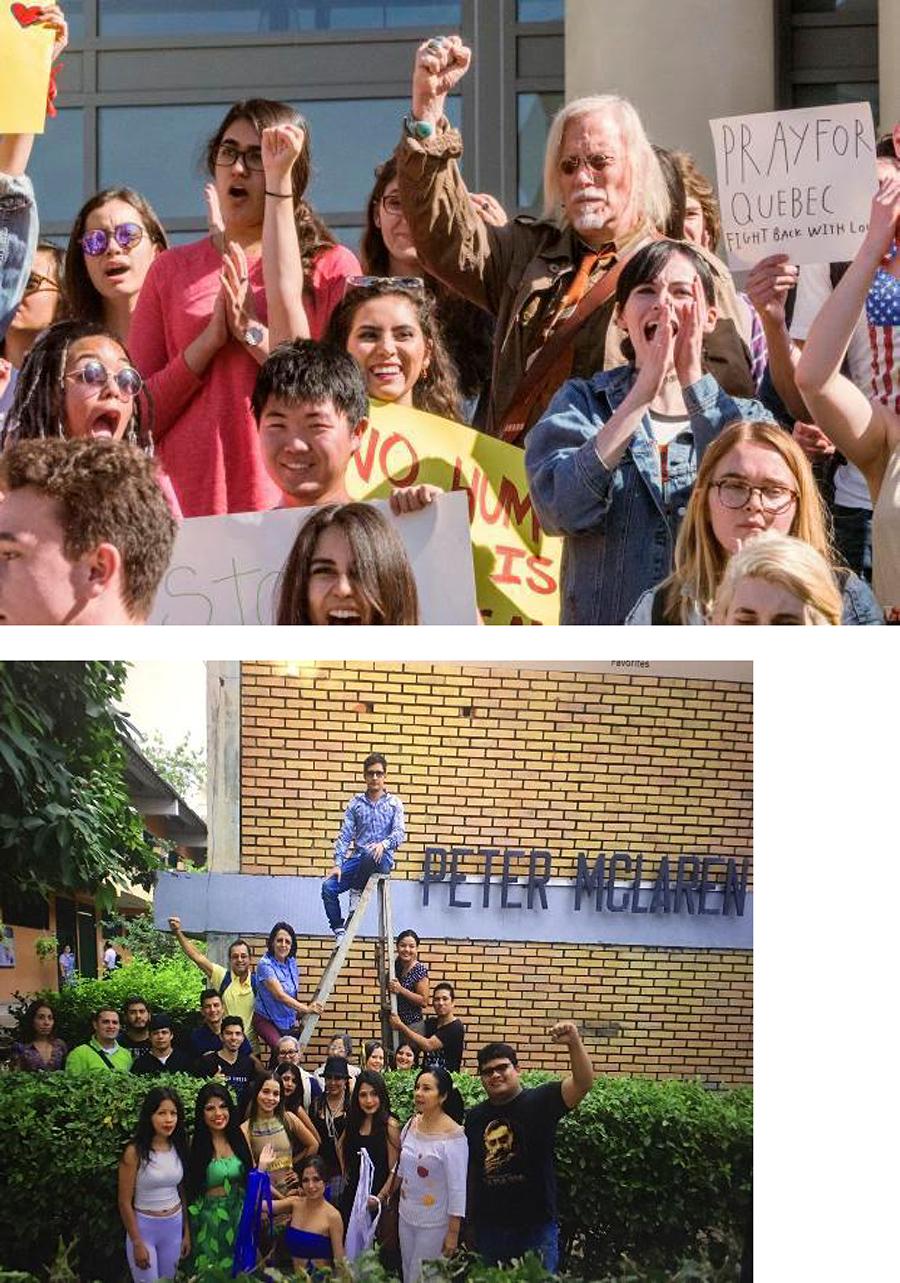

Figure 2 Left: Peter McLaren and students at Chapman University/Right: A school building (in La Escuela Normal Superior de Neiva) named after Peter McLaren in Neiva, ColombiaSource: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

Interviewers (I): Dear Professor Peter McLaren. It is with immense joy that we received your acceptance to grant this interview about Paulo Freire to our journal. We are grateful for your availability and generosity in sharing your experiences with Freire and his relationships with Critical Pedagogy in the United States.

To start this interview, we would like you to tell us a little about your life and education, as well as how you met Paulo Freire.

Peter McLaren: I grew up in a working-class family in Toronto, Canada. My mother had some medical problems and had to have a hysterectomy when I was young, and so I was the only child. I did not enjoy school and in fact I barely remember much of my life in school until I went to college. I think I must have repressed much of this part of my life for reasons that I am unable to fully fathom. My mother was a wonderful woman, very kind and generous and my father was a gentle and kind giant at 6 feet 3. He didn’t talk much about his 6 years in Europe fighting the Nazis but I am sure many of his experiences during WWII traumatized him. My uncle was a war hero with the Royal Navy, helping to sink the German battleship, Bismarck. The dominant adult males in my life were very conservative politically.

In the 1960s everything changed, and I became a hippie. At 19, I hitchhiked to the US, to Los Angeles and San Francisco and participated in protests against the Vietnam war. I read my poetry in coffee shops and met some cultural icons at that time such as Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. I met some Black Panthers in Oakland and took part in some political demonstrations. When I returned to Canada, I studied English literature at the University of Toronto, majoring in Old English (Beowulf) and Middle English (Chaucer) and then went to Waterloo University to study Elizabethan Drama (Shakespeare). But during these years I kept up with what was happening politically, and some of my professors were American draft resisters who had left the United States for Canada to escape the Vietnam War. Many of my friends were taking drugs. My two best friends committed suicide.

Upon graduation, I took a job teaching grades 7 and 8 in a wealthy village. After one year I came to the conclusion that these young people from wealthy families were going to get into college and university despite whether or not they had good teachers, simply due to their class background. I went looking for another challenge. I took a job in an area of Toronto known as the Jane-Finch Corridor. It had a reputation as a dangerous neighborhood. A cluster of government subsidized high rises flanked the school. Teachers did not last long in this school. But I loved the students and the principal was amazing. He took a sledgehammer to the wall of his office, and smashed it into pieces so his office could be easily accessible to all students. He replaced his steel desk with a small wooden table and replaced his chair with a rocking chair. All day long students came to see him for a hug. He was known as the hugging principal. I followed his lead and threw out all of the desks and chairs in my classroom and filled the room with pillows and comfortable furniture. I found a pair of drums and for a month the students and I took turns drumming. Test scores went up. I wrote a book about my experiences, many of the pages documented violence and despair among the students. The book became a Canadian best seller. However, I made the mistake of not analyzing my experiences in the book. Later, after getting my Masters degree in Education at night, I was accepted to the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto for a PhD. That is when I learned about Paulo Freire.

I had heard that Paulo had visited the university but I had missed his talk. And yet there was no mention of Freire’s work in the official curricula for the courses that I was taking. Nor was their official mention of other critical scholars. I found out who they were by talking to students in other programs, and studied their works on my own. I finally was able to get a videotape of Paulo being interviewed. The year was 1980.

I met Paulo in person in 1985 at an annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. He had filled an auditorium with 500 people. Clearly, North American educators were discovering who he was. I was close friends with Henry Giroux and Donaldo Macedo who were close to Paulo. I was surprised to learn from Paulo that he knew my work and spoke highly of it. I had no idea that he was familiar with my work. In fact, he wrote a Preface to two of my books. In one of the Preface’s he described me as his “intellectual cousin.” That revealed to me the generosity of his spirit. He invited me to Cuba for a conference but when I arrived in Havana he had already left, but I was to meet many educators from Brasil, Mexico and other Latin American countries, who invited me to give talks in their home countries.

Paulo invited me to his home in Brasil and even helped to translate one of my talks in São Paulo. Other educators invited me numerous times to Brasil, to Porto Alegre, to Florianópolis, Santos, Rio de Janeiro, Santa Clara, Santa Maria (Rio Grande do Sul), Uberlandia, to Salvador in Bahia, and Cachoeira. I attended Umbanda and Candomblé ceremonies, thanks to Afro-Brazilian members of the Workers Party, and was able to visit many different favelas, and was even presented with a plaque for helping to defend Afro-Brazilian religion. I even watched a live football game between Brasil and Argentina. Brasil had captured my heart early on. Paulo had opened the door and made all of this possible.

I: In your narrative you seem to indicate that you got close to Freire since the time you worked at the Jane-Finch Corridor school. Your political and loving commitment to the transformation of students at this school already announced your “intellectual kinship” with Freire, as he himself states in the preface to the book you wrote: Critical Pedagogy and Predatory Culture. How do you explain this “kinship” and what has changed in your pedagogy, your intellectual production and your struggles since you got close to Paulo Freire?

Peter McLaren: Yes, correct. I left teaching in the Jane Finch Corridor school in 1979. I first heard about Paulo in 1980. I eventually met Paulo five years later, in 1985. Yes, I did share some ideas about pedagogy and certain values about emancipation, freedom and the politics of liberation prior to reading Paulo’s work. And yes, I would agree that I had a natural affinity towards Paulo’s work. When I started to engage Paulo’s work, I was determined to understand his ideas as best I could. Paulo brought a whole new range of meanings for me to consider, he opened doors to my understanding of politics and pedagogy in ways I had never managed.

I: What I meant is that your affinity with him was natural and existed even before you two met. It was already expressed through emancipatory work and the ideal values you had. Your convictions brought you two closer, even before getting to know Freire. I have your book Critical Pedagogy and Predatory Culture translated into Portuguese and in its preface Paulo Freire mentions the “intellectual kinship” he felt for you. Thank you for the explanation you sent anyways! It enriched your narrative for me!

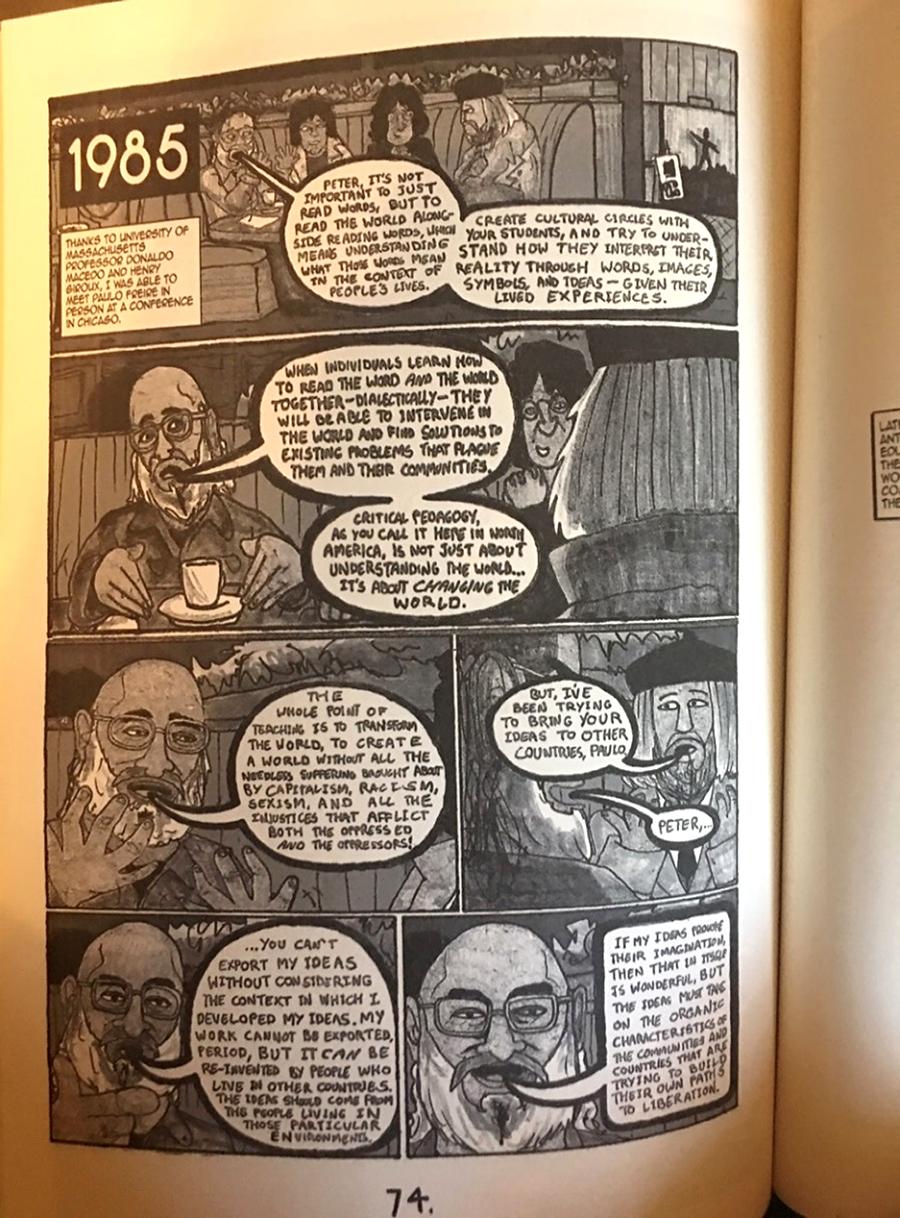

Peter McLaren: I felt a close affinity with Paulo, and was struck by his humility and his kindness. His was the most brilliant mind I had ever encountered and the tenderest of hearts. And the spirit of a warrior! When I first met him in one of the big hotels in Chicago during a conference, he was surrounded by dozens of admirers. When he entered a room, people stood up from their seats and there was loud applause. This happened everywhere he went. I think Paulo was surprised by the attention he received, and he always responded with patience, courtesy and humility. He would sometimes approach me in a fatherly fashion and offer me advice. Once I told him that I was discussing his work in talks I was giving in various countries in Latin America. In a friendly fashion, he cautioned me not to “deposit” or “import” his ideas across national borders but to invite teachers and activists from other countries to translate his ideas in the context of their own specific struggles [Figure 3].

Figure 3 From the book Breaking Free: The Life and Times of Peter McLaren1 Source: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

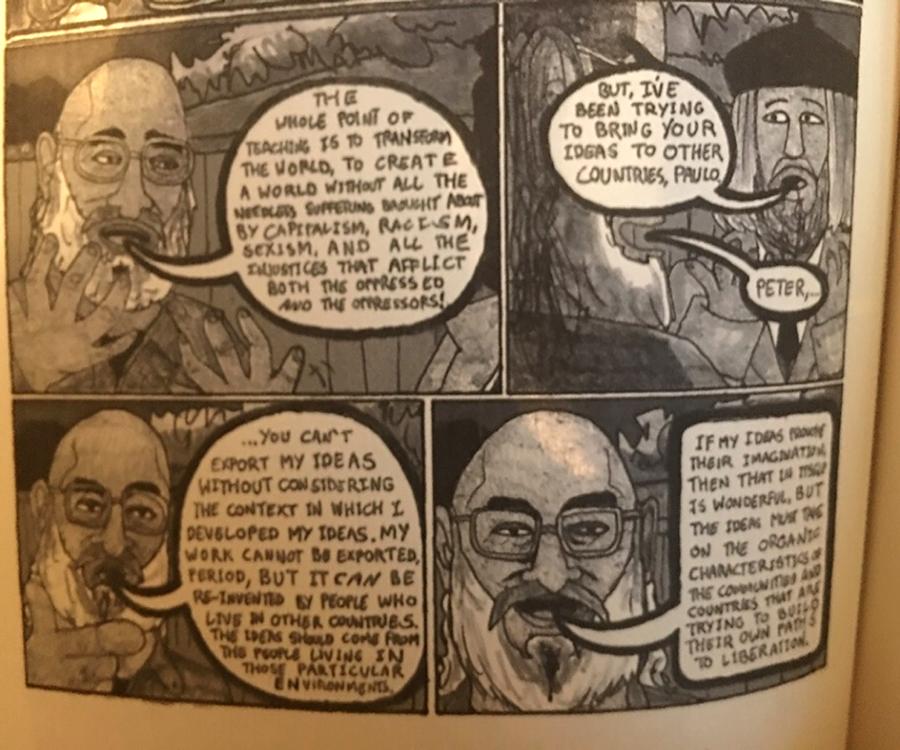

President Chavez appreciated those of us who were working in Venezuela with Freire’s ideas and once he emphasized to me that any critical pedagogy that would emerge from the struggle of Venezuelan communities would be Venezuelan. Chavez was an admirer of Freire and he knew enough about Paulo’s ideas to understand the importance of what happens to theories when they “travel” from one country to another. Paulo would always remind me that he saw the world through Brazilian eyes, and that the complex web of reality made it impossible to “export” his work into other countries without considering the contextual specificity of the communities involved—he understood that people would take up his work in different ways and recreate and reinvent his ideas according to their own cultures and histories—including their myths, and those forces that mediate their lifeworlds. He would always say, “Peter, don’t export me, but encourage my ideas to be reinvented” [Figure 4]. He knew how important it was for struggling communities to navigate the contradictions inherent in asymmetrical political systems of power and privilege sustained by a patriarchal and colonial capitalist system. He exhorted those who took up his ideas to re-read and re-write him in their own ways, that is, in the ways in which they have come to read the word and the world. Freire did not want his work to be imposed on various groups through mechanistic, technocratic, or instrumentalized methodologies. When I gave talks about Paulo’s work, I would restrict myself to discussing how Paulo’s work influenced me in my North American contexts—how Paulo’s ideas helped me to re-read the word and the world in ways in which I had never considered. Likewise other communities would judge the relevance of Paulo’s work in relation to their own specific struggles.

Figure 4 From the book Breaking Free: The Life and Times of Peter McLaren2 Source: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

Paulo’s emphasis on praxis meant that such struggles could lead to outcomes that were achievable or potentially feasible. Paulo’s work became a baseline for my work although I could never live up to the demands his work placed on me—such as Paulo’s notion of unfinishedness and transcending our limit situations and transforming them into untested feasibilities as part of our ontological vocation to become more fully human and to create spaces where justice can be affirmed. Paulo’s teachings sent me on a voyage of utopian dreaming for a socialist future, and I always tried to keep in mind Ernst Bloch’s distinction between concrete and abstract utopias and the importance of an educated hope emerging through the praxis of revolutionary movements, among grassroots organizations. Paulo taught me to focus on concrete utopian thinking rather than abstract utopias which are often blueprints envisioned by bourgeois intellectuals to be put into effect at some distant point in the future. Abstract utopian thinking is often disconnected from the struggles of the immiserated, the impoverished, the disinherited.

Around 1995, I began to revisit Marx’s writings and this helped to deepen my critique of political economy. We are all unfinished beings — and our purpose is not a Faustian bargain with the guardians of capital but rather humanization, which brings us closer to our goal of liberation. Revolutionary change means shifting the tectonic plates of unreason by dialectical thinking thus moving the geography of reason towards those precincts more hospitable to Marx. An historical materialist approach to understanding the role that capital plays in our social universe provides a crucial basis for overthrowing the present and inaugurating a new world, for issuing forth a novel present in which are planted the seeds of revolutionary socialism.

As Freire made abundantly clear, we need to transcend our limit situations, because beyond them is what Freire called untested feasibility, ways of being and becoming more human, where the words that we speak can hear themselves spoken. This helped me to focus on forms of human social reproduction that transcended value augmentation, the value form of labor, forms of existence that moved beyond forces and relations of capitalist commodification. Over time I became convinced that what we need is a robust transition to a new ecosocialist civilization. I began to consider the work of Marx and Freire in light of putting an end to the planetary destruction by the capitalist mode of production.

We live in theCapitaloceneand under the influence of the negative consequences of the post-digital revolution, sometimes called the Fourth Industrial Revolution. How can we create an alternative to capitalism, combining the insights of eco-feminism and eco-socialism—this is still one of the major directions of my work. I became very interested in Raya Dunayevskaya’s work, especially her notion of absolute negativity, the negation of the negation, and the positivity that can be extracted by the negation of the negation. But I don’t want to get too theoretical here. I really do think we need to think of Marxism less as a mechanical approach that moves through prescribed stages, and more as a guiding myth, as the great Peruvian Marxist, Mariátegui, understood the meaning of the term. We need to feel we are part of a grand movement of change that is made more feasible in our daily efforts in challenging the system—such as in the recent protests we have seen in the United States and throughout the world after the murder of George Floyd by a Minnesota policeman.

Yet the pain and suffering that the immiserated, impoverished and disinherited strew throughout their personal narratives at this historical inflection point do contain instances of hope that a new day will be born. Consider the fact that these protests have been liberated from geographic rootedness: the demonstrations that broke out over the police murder of George Floyd sparked multiracial events in 2,000 U.S. cities, where 26 million people participated. But the protests against police abuse, racism and social inequality also broke out at the same time in 4 dozen European and Latin American countries, including several African countries. This has been unprecedented. The protests became more differentiated and at the same time more collective, calling for prison reform, defunding the police, justice for transgender peoples, an end to sexual violence as well as to systematic racism, sexism and the school-to-prison pipeline.

It is gratifying to see such large multi-racial groups rise up and protest the horrors of the growing slide into fascism that we are witnessing around the world at the moment, headlined by Trump, and Bolsonaro, who is sometimes called the Trump of the Tropics. I think we should take Trump and Bolsonaro in aterreirode candombléand feed them each a bowl of Ayahuasca, and let Exú take them on a journey, similar to that of Dicken’sA Christmas Carol, where they could both revisit their past, glimpse the future of the planet and be converted from fascist-loving tyrants into champions of democracy in the present. Having witnessed a devastated planet that has resulted from their shameful environmental policies and their inaction on climate change, they would witness generations of young people living disposable lives without futures, and they would undergo a personal commitment to an ecosocialist future. Yes, it is nice to live in a fantasy sometimes, to take away for a brief moment the sting of the present. But it is time that we wake up and realize that the only way to rid ourselves of these brutes is for the people to rise up and throw them out of office.

I: Professor Peter, your explanations made me think about various topics for us to talk about. But, as I need to choose one of them to go deeper, what really got me thinking was you said that Paulo Freire always told you: “Peter, don’t export me, but encourage my ideas to be reinvented.” And then you also said: “When I gave talks about Paulo’s work, I would restrict myself to discussing how Paulo’s work influenced me in my North American contexts — how Paulo’s ideas helped me to re-read the word and the world in ways in which I had never considered”. These specific parts of the answer brought me two big curiosities:

First, in what aspects did Paulo Freire influence your reading of the world and your reading of the word in the North American context? Second, what reading do you take of the world today, a world in which we see people like Trump and Bolsonaro come to power, and how to reinvent Freire’s legacy as educators to seek the transformation of this world, helping to build less unjust and more respectful human relationships as he defended?

Peter McLaren: Paulo taught me to get in touch with my working class roots, that go back to Ireland and Scotland. He turned my life as a teacher upside down. He helped me to understand my own racial privilege in a multiracial and multicultural society. He inspired me to visit Latin America, and to take lessons I learned there to the streets the United States—and this helped me to understand the systemic racism, sexism and class exploitation that was at the heart of the United States – the genocide of indigenous populations, the brutal and inhumane slavery that was embedded in the plantation economy, the ideological systems embedded in the mass media, the imperialist wars, the role of the CIA throughout the world, the hypocrisy braided into the concepts of American exceptionalism and the American Dream, the oppressive role played by the evangelical Christians who practice the “prosperity gospel” that equates salvation which material riches. Paulo taught me how being a teacher means becoming involved in a path that requires a life devoted to an unrelenting pursuit of justice, despite the fact that the goal can never be fully foreknown or finally attained.

Paulo taught me to read history, the best I could, from the persepective of the victims, from the perspective of the people. I became an admirer of Howard Zinn’sA People’s History of the United States. Paulo taught me to replace instrumental reason with critical, dialectical rationality, in order to enter a dialogical relationship with the oppressed and non-oppressed, and to foster popular dissent in the interests of building a society where oppression can be rooted out, and this required that I better understand the importance of workers and communal councils and community decision-making structures. Paulo risked his life to help those who suffered as a result of being disproportionately affected by the cruelty of capitalism’s social relations of exploitation. Paulo taught me that education entails praxis, beginning with ethical action, not with correct doctrine.

This action is premised on a belief in the capacity for human goodness and begins with acting ethically. Human beings revise their thinking given various changes in their circumstances, and educators must themselves be willing to be educated. Revolutionary practice, or praxis, has to do with what Marx referred to as “the coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-change.” That became clearer as I began to understand Paulo’s work. Protagonistic or revolutionary agents are not born, they are produced by circumstances. To revolutionize thought it is necessary to revolutionize society. All human development (including thought and speech) is social activity and this has its roots in collective labor. Paulo sent me on a journey, and I am not finished yet.

I have not always been able to be a Freirean because Paulo set the standards so high. But Paulo’s life and work helped me late in life to connect with the spirituality that informs all of our lives, whether we recognize it or not. Nita Freire also helped to inspire me. For me, it meant reconnecting with my Catholic faith and liberation theology, It has made me feel a deep sadness and anger at what Brasil’s fascist president, Jair Bolsonaro, is doing to Brasil. He is a “macho” man who is at war with the educational left of his country, whom he decries as “cultural Marxists,” and is playing the political fiddle as his country’s Amazon rainforest goes up in flames. This is the same man who is trying to replace Paulo Freire as the Patron of Brazilian Education with a 16th century Spanish Jesuit missionary, Saint Joseph of Anchieta, and who, armed with the logic of instrumental reason and the mental acuity of someone afflicted by an after-lunch stupor, has refused $20 million in aid money offered by G-7 nations to battle the fires that are wreaking havoc on one of the world’s greatest sources of biodiversity, a refusal promoted by a slight on Bolsonaro by French President Emmanuel Macron.

Even the spirit of Chico Xavier, summoned from the dead by the followers of Allen Kardec, cannot halt the forces of deforestation any more than he can dampen the government’s enthusiasm for the illegal “sweetheart deals” it has struck with the Brazilian mining and logging industries. So Bolsonaro doesn’t seem to care about fighting “anthropogenic extinction” or ecological collapse or climate change. How can we escape the probability of extinction, especially as it is aided and abetted by policies of the “new barbarians” headed by Bolsonaro and Trump, policies designed to reduce environmental protections and to allow the destruction of four million hectares of forest in South America every year?

I am tired of Trump’s juvenile theatrics and those of Bolsonaro. He can now boast he has survived Covid-19 because of his past as an athlete. So he goes on trips to supermarkets and bakeries and shakes hands and takes selfies without gloves or a mask while Trump ridicules Joe Biden for wearing a mask. Trump has also survived Covid-19 and brags about how he was only sick for a few days because of his excellent genes. Bolsonaro has threatened to rid Brazil’s education system of all “Marxist rubbish” and to use a political “flamethrower” to erase the historical memory of Paulo Freire throughout Brasil. Trump is now saying that education designed to help students understand white privilege and racism is un-American. He doesn’t want white people to feel uncomfortable for their complicity in slavery, for systemic racism, for a capitalist system driven by racism. Create a safe space for the white people, for their complicity in racialized social relations! Here Trump is pandering to his “base” of supporters and enabling more racism to occur. He is “normalizing” racism. He is “weaponizing” white supremacy, and white militia movements armed with automatic rifles are growing under his leadership. They love Trump for making “racism” permissible again. Let’s keep the Blacks and Latino/as from the suburbs! Make the suburbs great again for White people!

Both Trump and Bolsonaro need to take a seminar with Leonardo Boff. Maybe Boff can visit them and give them a tutorial on the life of Saint Francis when these leaders are both in prison.

What do you do when your pai-de-santo, your babalorishá, manifests Exú when you know Exú can be capricious as well as kind and loving? Once a lawyer from Brazil’s Partido dos Trabalhadores told me that members of an Umbanda group where we once celebrated together a feast of Pomba Gira saved her daughter’s life through a spiritual intervention when her daughter was undergoing a tonsillectomy.

These are questions I’ve tried to answer since my participation in Umbanda ceremonies decades ago. Does a scientific explanation really matter to those historically oppressed Brazilians who, during celebrations in their terreiros, are possessed by their orishas? I have never witnessed anything hateful at the heart of this religious practice. It is filled with outpourings of love and dedication to helping others. Umbandistas also worship Jesus. Yet they are constantly coming under attack, being falsely accused of practicing black magic. I would rather be in their company than with those prosperity-gospel, praise-the-Lord, fire-and-brimstone preaching protestant evangelicals who receive financial support from the U.S. government to broadcast their missions throughout Latin America. Both the Brazilian and US governments are worried about liberation theology taking root again within the Catholic Church so they are happy to support fundamentalist evangelical protestants who preach patriotism, nationalism, and are pro-capitalist. The government of Bolsonaro, I am sure, does not want liberation theology to take further root in Brasil.

Because one of the foundational positions of liberation theology is that the exploitation and alienation of human beings from their own ‘species being’ results from the sin of greed, and the social relations and forces of capitalist production. Governments that pay total allegiance to the god of capitalism, whose leaders benefit from neoliberal capitalism, and that are led by fascists and authoritarian populists don’t want the ‘personal’ Jesus of their citizens to meet Karl Marx. They must be kept wide apart for ideological reasons. Liberation theology emphasizes action over doctrine—what those of us in the critical pedagogy movement refer to as ‘praxis’—and this term is very closely aligned with the revolutionary praxis of Marx and Freire.

I learned this from visiting the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil, and from witnessing community initiatives throughout North and South America that have been influenced by the teachings of Paulo Freire. A Black Theology of Liberation has now a strong presence in African American communities, and there exists strong proponents of feminist theology, postcolonial theology, reconciliation theology. With Paulo Freire no longer in this earthly dimension of existence we must rely on those whose spirit and intellect have been touched by Freire – and I find this in the work of those teachers, community activists and priests who are living out Freire’s pedagogical praxis in their barrios, favelas, communities and also in universities and theological seminaries.

They are helping us through their lived experiences and examples to better understand Freire’s life and mission. In this way, Freire lives! The fascists can try to ignore Freire or attack Freire, but they will never kill Freire’s spirit. Paulo Freire lives! Long after Bolsonaro and Trump are forgotten, Freire's spirit will be remembered and revered for his gift to humanity – a pedagogy of love!

According to Paulo, we become conscious of and transcend the limits in which we can make ourselves through externalizing, historicizing and concretizing our vision of liberation, as we challenge the psychopathology of everyday life incarnated in capitalism’s social division of labor. Paulo advises us to refrain from separating the production of knowledge from praxis, from reading the word and the world dialectically. This taught me that praxis serves as the ultimate ground for advancing and verifying theories as well as for providing warrants for knowledge claims. These warrants are not connected to some fixed principles that exist outside of the knowledge claims themselves but are derived by identifying and laying bare the ideological and ethical potentialities of a given theory as a form of practice. This is Paulo’s pedagogy of the concrete, his dialectics of the concrete.

We take our everyday social relationships and practices and try to examine their contradictions when seen in relation to the totality of social relations in which those particular relations and practices unfold. Thus, we have a backdrop against which we can read the word and the world historically. This enables us to live in the historical moment as a subject of history and, like Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, to see that human “progress” has left a world devastated by violence and destruction. We link our own history to the struggles of oppressed groups. This process is not simply an effect of language but pays attention to extra-linguistic forms of knowing, forms of corporeal and praxiological meanings that are all bound up with the production of ideology.

Meaningful knowledge is not solely nor mainly the property of the formal properties of language but is enfleshed – it is sentient, it is lived in and through our bodies, the material aspects of our being. It is neither ultra-cognitivist nor traditionally intellectualist. Knowledge, in other words, is embodied in the way we read the world and the word simultaneously in our actions with, against and alongside other human beings. We can’t transform history solely in our heads! But language is at the same time important. As Freire notes, “Within the word we find two dimensions, reflection and action, in such radical interaction that if one is sacrificed – even in part – the other immediately suffers. There is no true word that is not at the same time a praxis. Thus, to speak a true word is to transform the world”. True words require actions.

The world in which we speak our words must be changed in order for those words to be true. Words can only come to life when we use them to effect change. Do our words encourage dialogue and engagement with others? The words of Trump bring fear and hatred and division. His words are not true, they are shallow, they are hollow. The same with Bolsonaro. Freire teaches us to name our world and to humanize it. The words of Bolsonaro are spoken from above, from the precincts of power, they are dominative, not dialogical. They do not encourage reflection but only obedience. It is the same with Trump.

Paulo did not wish simply to organize political power in order to transform the world; he wished to reinvent power as power with the people, not power over the people. Political power, of course, is based on economic power. Freire believed that resources for a dignified survival should be socially available and not individually owned. The history of the rich is immortalized because their words are used to defend the interests and privilege of the ruling class. It is a fatalistic way of thinking about the poor that rationalizes poverty as a constituent condition of living in a class-divided society. Such a fatalism also leads to political immobilization as teachers focus on “techniques, on psychological, behavioral explanations, instead of trying or acting, of doing something, of understanding the situation globally, of thinking dialectically, dynamically”.

Very often the rich are culturally progressive but economically reactionary. Freire taught me that dialectical inquiry should be at the heart of “the act of knowing” which is fundamentally an act of transformation that goes well beyond the epistemological domain. It must reach into the real world of others. Dialogic education is, for Paulo, a path of providing opportunities for students to recognize the unspoken ideological dimension of their everyday understanding and to encourage themselves to become part of the political process of transformation of structures of oppression to pathways to emancipation – that is, to pathways to freedom. We cannot escape history. That is a powerful lesson that I learned from Paulo. Paulo wrote: “You must discover that you cannot stop history. You have to know that your country (the U.S.) is one of the greatest problems for the world. You have to discover that you have all these things because of the rest of the world. You must think of these things”.

I once wrote this description of Paulo for a book edited by Tom Wilson, Peter Park and Anaida Colón-Muñiz calledMemories of Paulo:

He was a picaresque pedagogical wanderer, a timeless vagabond linked symbolically to Coal Yard Alley, to Rio’s City of God, to the projects of Detroit and any and every neighborhood where working men and women have toiled throughout the centuries, a flaneur of the boulevards littered with fruiterers and fish vendors and tobacco and candy stalls, the hardscrabble causeways packed with migrant workers and the steampunk alleys of dystopian dreams.

This man of the people was as much at home in the favelas as he was in the mango groves, a maestro who would cobble together the word and the world from the debris of everyday life, from its fury of dislocation, from the hoary senselessness of its cruelty, from its beautiful and frozen emptiness and the wrathfulness of its violence. And in the midst of all of this he was able to fashion revolutionary hope from the tatters of humanity’s fallen grace. This was Paulo Freire.

Paulo Freire, he has found a place in our hearts, and as a fighter he has found a place in our protagostic struggle to build a better world.

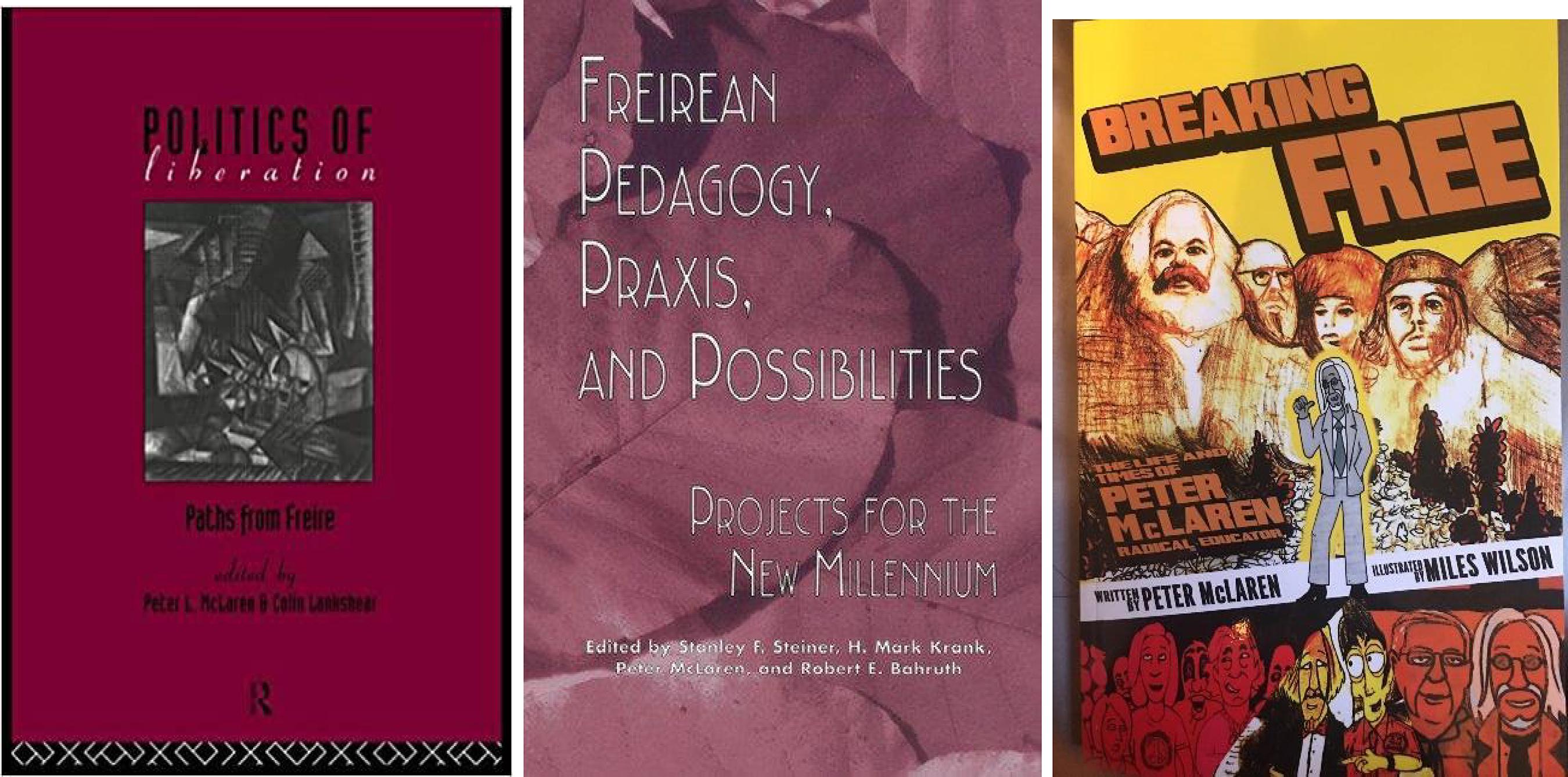

I: Your answer makes explicit the profound influence of Paulo Freire in your Critical Pedagogy, the critical, revolutionary, radical pedagogy of Peter McLaren. So I would like you to tell us about it (Figure 5).

We started this interview in order to learn about Peter McLaren's personal and professional trajectory, we talked about Paulo Freire and found out what Peter learned from Paulo. Now we return to Peter and his work in the second decade of the 21st century. So, tell us a little bit about how you put your critical pedagogy into practice at university and elsewhere in the USA. What results have you achieved with your work so far? Could you please send us photographs of you with Paulo Freire and also of your work to integrate and enrich the interview?

Figure 5 Left: Books about Paulo Freire/Right: Graphic Novel about Peter McLarenSource: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

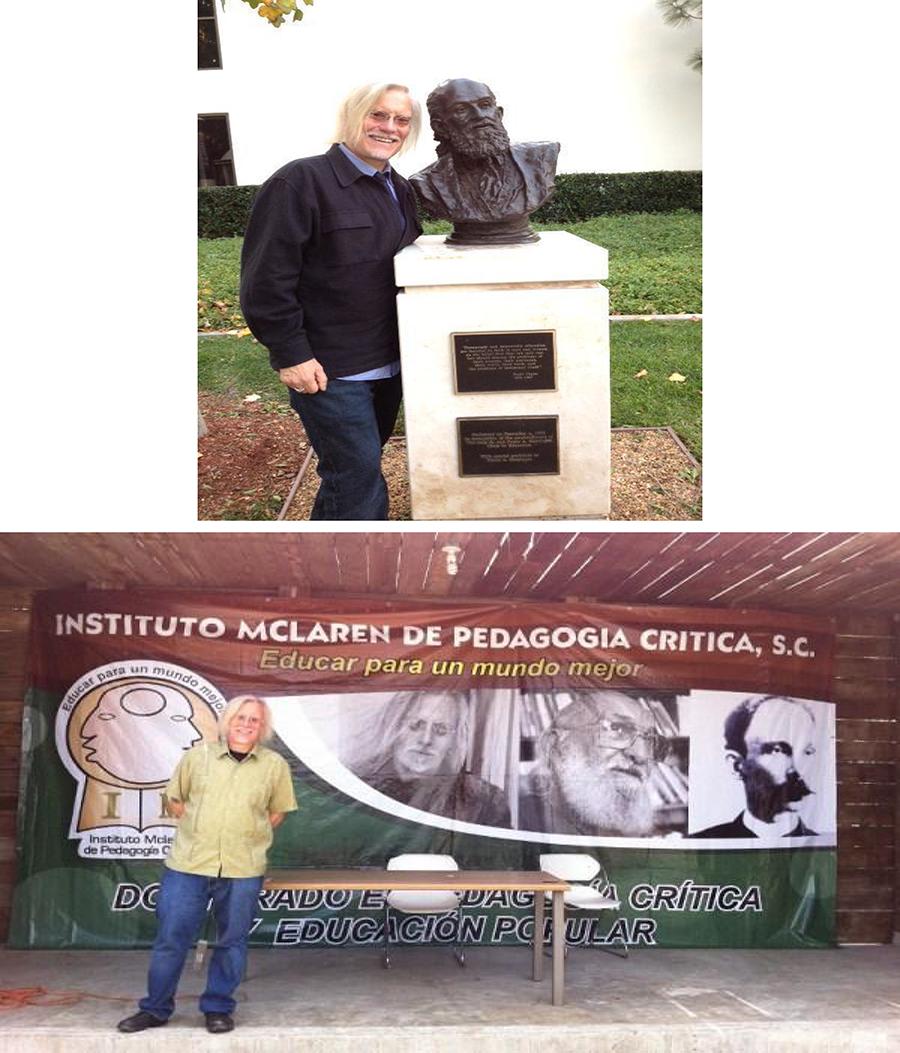

Peter McLaren: In 1995 my work became fundamentally Marxist humanist in orientation, and pedagogically I have always been a student of Freire. And I am a great admirer of Nita Freire, whose work has been helpful to many and to many of us in critical pedagogy. Donaldo Macedo’s work with Freire has been very important in my understanding and appreciation of Paulo’s work. I was very lucky to have joined The Paulo Freire Democratic Project at Chapman University [Figure 6] after being a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. The professors who belong to the Paulo Freire Democratic Project are wonderful colleagues who have taught me how to engage with communities surrounding the university – Lilia Monzo, Suzanne SooHoo, Anaida Colon-Muniz, Jorge Rodriguez, Catherey Yeh, Kevin Stockbridge, Gregory Warren and Gerri McNenny. We believe critical pedagogy has the potential to rehumanize our future if we can challenge our dehumanized material (commodity) culture by a praxis-oriented pedagogy and are able to revolutionize the political and economic institutions in the public interest rather than for private gain. That means building for a socialist future. All education today needs to focus on building for a socialist future. Our planet is burning! We need to reclaim our humanity and the power of critique. Some are looking to communism as a new frontier, rethinking many of its major concepts, others are employing a socialist strategic offensive.

Figure 6 Left: Peter McLaren beside the sculpture of Paulo Freire at Chapman University, California, USA/Right: Peter McLaren at Instituto McLaren in Ensenada, MexicoSource: Peter McLaren’s personal file.

Now when you ask me what progress I have made, it’s difficult to evaluate, because it is very difficult to make progress when you are a revolutionary Marxist and Catholic social justice worker who follows the path of liberation theology and is a major critic of the conservative wing of the Catholic Church – and live in the United States! My work appears to be more engaged outside of the United States. Here, in my adopted country, my ideas are seen by the majority of the population as radically extreme. That is because anti-communism and socialism have been weaponized by Republicans and many Democrats as the greatest threat to democracy. In fact, socialism in reality is the only hope for democracy to prevail. I am not the person to ask how successful I have been. That is a task for others to judge.

I have worked as part of a larger community of critical educators and together we have helped to build the field of critical pedagogy – there are courses in critical pedagogy in education, in the field of law, in psychology, in sociology, in English composition. Paulo’s work has been engaged in all of these fields. He paved the way for all of us. Of course, in the academic field, critical pedagogy has been successful since the topic of “social justice education” is now very common in teacher education and graduate classes in education. But there is still only a very few Marxists in the graduate schools of education and across other fields as well. Marxism and socialism continue to be attacked continually in the mainstream media.

I was accused of being “the most dangerous professor in UCLA” back in 2005-2006 because of my support for Cuba and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, and this attack on me and other professors at UCLA became an international story. And now it is worse in this country as we witness militarized forces attacking U.S. civilians. Donald Trump is psychotic, clearly. Recently, he has criticized the important and illuminating revolutionary historian Howard Zinn and he has attacked critical race theorists and he has described Black Lives Matter protestors as “terrorists.” In this respect Trump is as despicable as Bolsonaro, although Trump has the power to bring the world to ruins. Almost half the country supports a president who is racist, sexist, a misogynist, who is a white nationalist and white supremacist and who has turned the country into a pariah state. He is a malignant narcissist, is infected with misology, is a serial liar, and who lacks empathy for the poor. All of his decisions are predicated on what will get him reelected. He is basically a mafia leader, a criminal, a man-child who has divided the country to the point of almost tearing it apart. He has fired numerous inspectors general when they were beginning to investigate him. Then the federal attorney for the Southern District of New York, t started looking into Trump’s activities and Trump fired him. Trump’s climate and nuclear policies could virtually doom the planet. He has abandoned arms control, and the arms industry is very pleased with Trump.

Trump has just mentioned that he will create a commission on educational patriotism, and insists that teachers must teach the greatness of the United States. I have been calling for a “critical patriotism” which insists that the United States must recognize its many crimes as a country, through both its foreign and domestic policies. We do this through an historical materialist approach to understanding and interpreting historical events, through a dialectical engagement with what has transpired as a result of our activities in dealing with other countries. Of course we can celebrate the good things about this country – I’m not against that – but not at the expense of recognizing its historical crimes which the country has too often carried on the back of a settler colonialism, a military nationalism, the notion of American exceptionalism and the belief that God has ordained the United States to exercise its power in whatever way it pleases in order to protect its material prosperity and its way of life.

Critical pedagogy has always been an outlier as far as education goes. It’s been an oppositional “way of life” that challenges the anti-Kingdom of those who worship money and who follow the God of profit. It does this from the perspective of the most vulnerable, the poor, the powerless, whom Frantz Fanon referred to as “the wretched of the earth.” I have tried to work with many others as an internationalist educator in order to build alliances around the world, wherever it was possible. In my younger days I was able to visit numerous countries and I was able to see how capital dominates labor so powerfully. I think the recent protests in the US give us a powerful opportunity to make changes. Bernie Sanders, a socialist, was a highly popular politician before he was betrayed by the Democratic National Committee and I believe that we are closer to educating US citizens about socialism, although we have a long way to go. The social division of labor, or the realm of necessity, must be decommodified, and free of exploitation. We are a little closer to developing a counter-consciousness at one end, yet at the other end we face a growth in hate of the other.

I have been absolutely overwhelmed at and sickened by the pervasive and toxic racism that exists in the United States and how such large sectors of the population have fallen prey to neo-Nazi and white supremacist ideology. The Republican Party is the most dangerous political party in the world at this moment. The people have fallen victim to a dictator whom they actually believe cares for them. This to me is a stunning revelation. Herbert Marcuse asked whether the corporate state can be prevented from becoming a fascist state. With Trump, it is clear that no, it is not possible to prevent tyranny. In fact, it has happened in many aspects. We have capitalist overaccumulation and a failure of a reproduction of our labor force – so yes, capitalism is failing, it has failed! Our democracy has only a faint heartbeat, it is barely breathing. We need to resuscitate it through education – through revolutionary critical pedagogy. Through a critical pedagogy that benefits from the insights of Marx and Freire.

And of course Enrique Dussel argues that the modern violence of colonialism is legitimized by European, ego-centered philosophy. Which is why we must understand reality not from the center of the European socio-economic-political-ethno-militaristic worldview but from the exteriority of the margins, of the oppressed, the periphery that is demanded of revolutionary praxis. Only through conscientization, denaturalization, de-ideologization, de-alienation can we appreciate the praxis of the oppressed, of peoples of the periphery, as they reveal themselves to us through a self-unfolding epiphanic experience that includes a relativization of self and other. Reflecting upon the peripheral otherness of the poor, of the “wretched of the earth” relativizes the coloniality of power (Quijano) exercised by those who benefit most from the culture of domination, and reveals such a culture to be contingent and susceptible to change through the outlaw praxis of the marginalized, the oppressed.

Freire locates himself as allied with such decolonial logics and outlaw praxis which takes place, in theological terms, on the ground under the cross. Here, the question of “proximity” (Dussel) becomes important. Here the ethical question takes precedence over the epistemological. When a voice cries out for help from the wilderness, the question “where are you, where do you stand?” takes precedence over the epistemological question, “who am I?”. Do you stand in solidarity with the oppressed? Do you have respect for their life-worlds? Or do you regard the “other” as just as extension of yourself and your own Cartesion ego? Clearly the ethical question for Freire is the central one. European settler colonialism justifies its genocide, its ecocide, its epistemicide on the grounds of its superior role in God's providential plan for civilizing the world. And now its nuclear policy could take us on a path towards omnicide. While I can never fully know the experience of the other, I can stand in solidarity and commit myself to struggling to create the conditions of possibility for a social universe in which humanization for liberation is possible.

We are now confronting our Golgotha moment when we are about to re-crucify Jesus with teflon nails, transferring his salvific grace to Lady Luck’s slot machines, all lined up like tin soldiers in some shiny Vegas casino. We have acquiesced to a neoliberal business model to manage our schools of education. Universities should be sites where we can actualize our potential as protagonistic agents of self and social change. Capitalism has become a deeply inculcated ideological belief around which we have organized our lives. Trump is demanding we sacrifice our lives by opening up schools and businesses without providing the necessary resources to protect students and teachers from the coronavirus. Some politicians have spouted social Darwinist remarks arguing that the virus is clearing out the dead wood from the forest, meaning that elderly people must be made expendable so Trump can recover the economy before the election. The increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of global elites is ingrained into the system and should not surprise anyone who has been studying the co-optation of government by business interests and austerity measures. What should concern us is the massive increase in the panoptic surveillance of private citizens under the guise of terrorist threats, and what Trump calls "anarchy zones" in some cities such as Portland and Seattle. We cannot go backwards to neo-Keynesianism but must move forward to socialism. This means negating the barriers to socialism.

Self-movement is made possible through the act of negation by negating the barriers to self-development. But negation, is always dependent on the object of its critique. Whatever you negate still bears the stamp of what has been negated – that is, it still bears the imprint of the object of negation. We have seen, for instance, in the past, that oppressive forms which one has attempted to negate still impact the ideas we have of liberation. That is why Hegel argued that we need a self-referential negation – a negation of the negation. By means of a negation of the negation, negation establishes a relation with itself, freeing itself from the external object it is attempting to negate. Because it exists without a relationship to another outside of itself, it is considered to be absolute – it is freed from dependency on the other. It negates its dependency through a self-referential act of negation.

For example, the abolition of private property and its replacement with collective property does not ensure liberation; it is only an abstract negation which must be negated in order to reach liberation. It is still infected with its opposite, which focuses exclusively on property. It simply replaces private property with collective property and is still impacted by the idea of ownership or having something.

Of course, Marx thinks that it is necessary to negate private property. But this negation, he insists, must itself be negated. Only then can thetruly positive – a totally new society –emerge. However, as Peter Hudis argues, in order to abolish capital, the negation of private property must itself be negated, which would be the achievement of a positivity – a positive humanism – beginning with itself. While it is necessary to negate private property, that negation must itself be negated. If you stop before this second negation then you are presupposing that having is more important than being.

Saying “no” to capital, for instance, constitutes a first negation. When the subject becomes self-conscious regarding this negation – that is, when the subject understanding the meaning of this negation recognizes the positive content of this negation – then she has arrived at the negation of the negation. As Anne Fairchild Pomeroy notes, when a subject comes to recognize that she is the source of the negative, this becomes a second negation, a reaching of class consciousness. When a subject recognizes the positivity of the act of negation itself as negativity, then she knows herself as a source of the movement of the real. This occurs when human beings, as agents of self-determination, hear themselves speak, and are able both to denounce oppression and the evils of the world and to announce, in Freire’s terms, a liberating alternative.

Freire was deeply religious. Freire was highly critical of the role of theologians and the church – its formalism, supposed neutrality, and captivity in a complex web of bureaucratic rites that pretends to serve the oppressed but actually supports the power elite – from the perspective of the philosophy of praxis that he developed throughout his life. For Freire, critical consciousness (conscientization) cannot be separated from Christian consciousness. To speak a true word, according to Freire, is to transform the world. The ruling class, from Freire’s perspective, views consciousness as something that can be transformed by “lessons, lectures and eloquent sermons. But this form of consciousness must be rejected because it is essentially static, necrophilic (deathloving) as distinct from biophilic (life-loving), and turns people into sycophants of the ruling elite. It is empty of praxis. In other words, there is no dialectic, as conscientization is drained of its dialectical content. Freire calls for a type of class suicide in which the bourgeoisie takes on a new apprenticeship of dying to their own class interests and experiencing their own Easter moment through a form of mutual understanding and transcendence.

Freire argues that the theologians of Latin America must move forward and transform the dominant class interests in the interests of the suffering poor “if they are to experience ‘death’ as an oppressed class and be born again to liberation”. Freire borrowed the concept of class suicide from Amilcar Cabral, the Guinea-Bissauan and Cape Verdean revolutionary and political leader who was assassinated in 1973.

For Freire, insight into the conditions of social injustice of this world stipulates that the privileged must commit a type of class suicide where they self-consciously attempt to divest themselves of their power and privilege and willingly commit themselves to unlearning their attachment to their own self-interest. Essentially, this was a type of Easter experience in which a person willingly sacrifices his or her middle or ruling class interests in order to be reborn through a personal commitment to suffering alongside the poor.

This means examining poverty as a social sin. This means examining how the capitalist system has failed the poor and not how the poor have failed the capitalist system. If a person truly commits to helping the poor and the oppressed then that is equivalent to taking down all victims from the cross.

I: Your discussions bring up complex issues of our time, which lead us to countless reflections on how we reached this political, economic and social context that we live in Brazil and the USA, marked by the rise to power of inhuman, necrophilic, authoritarian, insensitive and violent people in several countries. One of the consequences of this context in Brazil is the dismantling and depreciation of public universities, both by the federal and by state governments, which aim the privatization of these universities.

So, now I ask you: what paths can be taken so that we can resist as educators and researchers, fighting oppression and acting to overcome inequalities by democratizing the university space?

Freire, among other announcements, indicated the path of unity in diversity - the union of the different in the fight against the antagonistic, which is not an easy task, but it is possible.

Peter McLaren: This is an important question. We need to know where our leaders stand today, how they manufacture reality, and how they incentivize the public into seeing the world as they do. Even without Trump and Bolsonaro, the public universities were under assault by university administrators and boards of governors in the thrall of neoliberal business models. Almost the entire lifeworld of the planet has been colonized be neoliberal capitalism. Bolsonaro and Trump don’t want public universities to succeed since they can better maintain control of the universities and the production of knowledge if the universities are private and for-profit institutions run by wealthy entrepreneurs who seek the stability of the market economy and private links to the ruling political party. But first we need to understand the political shifts in the larger political arena.

Trump’s tabloid presidency may seem comical to some of its critics who often compare it to a circus clown act, but a closer reading should give any student of fascism serious pause. We need to turn the spotlight on Trump’s fascination with being the übermensch, the strongman, a Nietzschean will-to-power demagogue, the Master of Chaos. Trump has purged his White House administration of non-loyalists, he has placed family members in positions of importance, drawing upon an us-against-them mentality; he has created an alternative reality in which the United States is under siege by Antifa and anarchists bent on death and destruction; he has lumped peaceful protesters with violent protestors, labeling them terrorists; he has used his political position to amass personal financial gain; he has withdrawn from international treaties and engaged in an isolationist politics; he brutally intimidates his political opponents; he has attacked the educational system for indoctrinating students with hateful leftist propaganda; he defines the nation around race, faith, and white ethno-nationalism as distinct from a humanitarian nation defined by rights and collective responsibilities; he has supported confederate statues and military bases named after confederate leaders.

Reaching a consensus with the left is deemed weak while the politics of brutality, force and the language of violence is championed. The theme of “law and order” is frequently invoked as a means of quelling feelings of mass insecurity during times of economic or political crisis. Fascist leaders are adept at creating imagined communities of friends and enemies. Journalists are described as “enemies of the people” and leftist intellectuals are declaimed as traitors, sabotaging the country. Fascists like to paint the country as targets of humiliation by other countries, enhancing the idea of the country being victimized by others, both by internal and external enemies. Fascists routinely discredit the election system and find ways to win the vote fraudulently.

In this climate, Freire’s message of unity in diversity appears to the fascist leader as a politics of appeasement to the left. Fascists have no use for appeasement or diversity, they want racial unity, unity of white European blood. Hence, they often warn that the white race is being taken over in numbers by non-white races, which they argue will bring about the decline of civilization. Fascist leaders take a masculinist approach to politics, often borrowing from ancient archetypes of the hero, the father figure, the knight in shining armor, the protector of the people (meaning white people). Trump is all about atmospherics—his presidency is about hectoring, pugnacious energy, barbaric energy, demagogic energy, incendiary rhetoric, propagandistic energy, shambolic energy. This all suits Trump’s logorrhea.

Trump has refused to denounce white supremacy in clear terms. Trump and Bolsonaro are social arsonists-they shatter and splinter the social cohesiveness necessary for any functioning democracy. Democracy is their enemy. This is why the Trump, the Racist-in-Chief, is attacking peaceful protestors and calling them terrorists. There have been more than 7,750 Black Lives Matter demonstrations held across the country in the last several months. Of those demonstrations 93 percent have been peaceful, according to numerous reports from Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative published in September. Trumpet-tongued Trump, the Imp of the Perverse, peers from the darkness of an Edgar Allan Poe nightmare, delighting in the deliciousness of the destruction. Trump is the Lord of Chaos, reveling in the death he has incurred, slurp-lipped at the thought of bodies writhing in pools of bloody devastation. He has fulminated against common sense, creating a world-wrenching apocalyptic narrative that he is protecting the United States from the evils of immigration and socialism.

Our universities have been colonized by the logic of neoliberal capitalism. To a large extent, the experience of the pandemic has derailed the academy’s quest for certainty. Right now uncertainty and its twin – fear of the unknown – dominates the popular narrative. Our entire way of being-in-the-world has shifted dramatically. We have been made more vulnerable to the cajoling of rightwing demagogues to continue to define our very being through the prism of homo economicus, the predominance of linear succession, of technocratic rationality. Our ideas of teaching are shifting as we are faced with working solely through our computers. True, there are some advantages to digitally mediated schooling, once we are able to overcome the digital divide and provide high quality broadband to all students around the world. But digitalizing pedagogy is also like hanging the sword of Damocles over your head. Will it turn out to be the pedagogy of choice for many students after the pandemic, for those students who travel long distances to campus? Is the future of teaching hyper-flex models that are partially online and partially in person classes?

We need to be critical in how we understand the relationship between epistemology and ethics. We need to prepare for more chaotic disruptions, to anticipate them, and to study ways of preventing them. There will be more crises. There will be more economic disasters. There will be rising food prices and more famines in parts of the world, there will be geopolitical fights over water. There will be military invasions. There will be existential issues that demand answers. Universities need to begin to focus their curricula on trying to anticipate what these crises will be, address these issues using the best information and analyses possible, in order to prevent more crises. Fortunately we have many strong Freireans working in our struggle to help defend democracy and socialism such as Juha Suoranta, Peter Mayo, Antonia Darder, James Kirylo, Henry Giroux, Donaldo Macedo, Petar Jandric, Ana Cruz, Sheila Macrine, Sonia Nieto, members of the Paulo Freire Democratic Project—and many others too numerous to mention.

Thus we need to rethink the epistemological and ethical underpinnings of education. We need to rethink how we utilize the resources of the planet and support public health, how we can seriously address climate change. The purpose of education must be refashioned towards addressing these issues. Can we envision a social universe outside of capital’s value form which is value augmentation or profit-creation? Can we take advantage of the new abnormal? How can we undress the machinations of a capitalism that has absolutely failed humanity in this time of the pandemic? Can we move away from our laser-focus on postdigital technocracy, commercial interests and measurement and accountability schemes and place more value on dialectical reasoning, Freirean dialogue and revolutionary praxis? Can we shift away from the competitive branding and marketing of our universities to the pursuit of both truth and justice? Can we take seriously Freire’s call for making education our ontological vocation for becoming more fully human? Can digitalization bring us closer together to becoming global citizens, and if so, at what cost? What does performing to standard mean with respect to online classes? Can it have a democratizing effect? Or can the rules and the interactive digital platforms that have been established favor the oppressor over the oppressed?

As a graduate student I took one class with Michel Foucault. It was the interactions I had with him when I took him to visit various Toronto bookstores that I valued more than the actual classes. For me, it was the cold breeze of walking the streets, watching Foucault’s scarf billow in the wind, the comments he made about the city, and his sense of humor that would have been lost had the class been an online experience. It was the smell of peach brandy tobacco smoke that wafted through the office during my discussions with another professor that made the most impression on me. In fact, I became a collector of pipes after the class was over. Being in the physical presence of Paulo was an experience to which online communication could not have done justice. Teaching in real time and space is important. Meeting in cyberspace only allows for a small range of communication cues. But for those who do not have the opportunity of having an in-person mentor, online classes are often the only option. Debates will continue over whether embodied knowledge is ultimately more preferable than virtually mediated spaces and cultures of reasoning over long periods of time.

What Needs to be Done

Let’s look at the curriculum. First, education must be focused on understanding the political economy of capitalism—from post-feudal times to present instantiations of financialization. Society, culture and social relations of production must be seen as interconnected. Systemic racism must be understood as inextricably linked to the legal system and the criminal justice system. Capital-perpetuated settler colonialism, sexism, racism, homophobia, and misogyny, misanthropy and misology must be examined for their interrelatedness, including the historically generated myths that have served to legitimize them. Classes must deal with the issue of climate change and scarcity, and technology-enabled extraction of natural resources.

I could continue but the point I want to make is that the main issue that drives the curriculum for liberation should focus on the various systems of mediation that have produced us as 21stcentury compliant and self-censoring human beings who appear defenseless in the face of nationalist calls for war, for ethnic chauvinism, for narratives championing imperialism and the coloniality of power. There should be a study of revolutionary social movements that have challenged these systems of mediation, and why some groups succeeded and why many of them failed.

I have only scratched the surface here. Clearly we need an education system that can move groups from a class-in-itself to a class-for-itself—that is, to a class that actively pursues its own interests. Certainly we need a mass movement from below to counter the much more advanced digitalisation of today’s entire global economy and society which has utilized the application of fourth industrial revolution technologies led by artificial intelligence (AI) and the analysis of ‘big data’, machine learning, automation and robotics, nano- and bio-technology, quantum and cloud computing, 3D printing, virtual reality, new forms of energy storage, etc.). But that will not be an easy task. But it is a necessary one, since we will be struggling against the formation of a global police state.

The sociologist William Robinson has warned that in the time of the pandemic we are able to see the acceleration of digital restructuring “which can be expected to result in a vast expansion of reduced-labor or laborless digital services, including all sorts of new telework arrangements, drone delivery, cash-free commerce, fintech (digitalised finance), tracking and other forms of surveillance, automated medical and legal services, and remote teaching involving pre-recorded instruction.” Hence, the giant tech companies and their political agents are able to convert great swaths of the economy into these new digital realms.

Robinson also notes that the “post-pandemic global economy will involve now a more rapid and expansive application of digitalisation to every aspect of global society, including war and repression.” We have an enormous task ahead of us. If we can make postdigital science work in the interests of the oppressed, rather the corporate elite, then we would be foolish not to try to strengthen our communal immune system. We have Paulo's legacy that will give us strength, both moral strength and intellectual strength. The strength needed to fight against repression in this time of fascist restoration.

Notes

REFERENCES

BENJAMIN, W. Sobre o Conceito de História. In: BENJAMIN, W.Obras Escolhidas. v. I. Magia e técnica, arte e política. Tradução Sérgio Paulo Rouanet. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1987. p. 222-232. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Parentesco intelectual. In: FREIRE, A. M. A. (org.). Pedagogia da tolerância. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2005. p. 245-247. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em