Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Práxis Educativa

Print version ISSN 1809-4031On-line version ISSN 1809-4309

Práxis Educativa vol.18 Ponta Grossa 2023 Epub Feb 16, 2023

https://doi.org/10.5212/praxeduc.v.18.20929.007

Thematic Section: Psychosocial perspectives on education in the pandemic period

The construction of the social thinking of teachers and pedagogical coordinators about the COVID-19 pandemic: a study in social representations*

**Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP).

***Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR).

****Univesidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

In this article, it was aimed to understand the social thinking in the face of the pandemic, formed by groups of female Education professionals - teachers and pedagogical coordinators - to understand their social representations about the COVID-19 pandemic process. Initially, it is reflected on the perspective of social representations and architecture of social thinking to address this topic. Subsequently, in a qualitative approach research, a Free Word Association Test on the word “pandemic” was applied, and it was asked to describe “how their experience with the pandemic was in their professional life. The data produced in 2020/2021 with 58 women, after being processed by the IRaMuTeQ software, allowed the Prototypical, Similitude and Descending Hierarchical Classification analyses, which triangulated to a traditional qualitative microanalysis complemented by thematic analysis, with theoretical support from the Theory of Social Representations and of Education Policies at that time, in Brazil, made it possible to apprehend their representations in the pandemic spatial-temporal context experienced.

Keywords: Social representations; Female Education professionals; Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Neste artigo, objetivou-se compreender o pensamento social frente à pandemia, formado por grupos de mulheres profissionais da Educação - professoras e coordenadoras pedagógicas -, para assimilar suas representações sociais sobre o processo da pandemia da covid-19. Inicialmente, reflete-se sobre a perspectiva das representações sociais e sobre a arquitetura do pensamento social para abordar esse tema. Na sequência, em pesquisa de abordagem qualitativa, aplicou-se um Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras, com a palavra “pandemia”, e solicitou-se que descrevessem “como estava sendo sua vivência com a pandemia na sua vida profissional”. Os dados produzidos, em 2020/2021 com 58 mulheres, após processados pelo software IRaMuTeQ, permitiram as análises Prototípica, de Similitude e Classificação Hierárquica Descendente, as quais, trianguladas a uma microanálise qualitativa tradicional complementada por análise temática, com aporte teórico da Teoria das Representações Sociais e das Políticas Educativas nesse momento no Brasil, possibilitaram apreender suas representações no contexto do tempo/espaço pandêmico experienciado.

Palavras-chave: Representações sociais; Mulheres profissionais da Educação; Impacto da pandemia da covid-19.

En este artículo se tuvo como objetivo comprender el pensamiento social frente a la pandemia, formado por grupos de mujeres profesionales de la Educación - docentes y coordinadoras pedagógicas -, para asimilar sus representaciones sociales sobre el proceso de la pandemia de la covid-19. Inicialmente, se reflexiona sobre la perspectiva de las representaciones sociales y sobre la arquitectura del pensamiento social para abordar este tema. En la secuencia, en enfoque de investigación cualitativa, se aplicó un Test de Asociación Libre de Palabras, con la palabra “pandemia” y se solicitó que describieran “cómo estaba siendo su vivencia con la pandemia en su vida profesional”. Los datos producidos en 2020/2021 con 58 mujeres, luego de ser procesados por el software IRaMuTeQ, permitieron los análisis Prototípico, de Similitud y Clasificación Jerárquica Descendiente, los cuales, triangulados a un microanálisis cualitativo tradicional complementado con análisis temático, con aporte teórico de la Teoría de la las Representaciones Sociales y de las Políticas Educativas en ese momento en Brasil, permitieron aprehender sus representaciones en el contexto del tiempo/espacio pandémico experienciado.

Palabras clave: Representaciones sociales; Mujeres Profesionales de la Educación; Impacto de la Pandemia de la covid-19.

Introduction

In this text, we report on the research conducted with the purpose of understanding the social thinking about the pandemic in a group of female professionals in Education - teachers and pedagogical coordinators - based on the understanding of their social representations about the process of the covid-19 pandemic.

In the last 50 years, Social Psychology has sought to develop studies that allow the understanding of the social thinking of groups or even populations of a nation. Moscovici (1961, 1984) was one of the authors who, when pointing out the inseparability of the individual and society, pointed out that: "It comes to be a banality to recognize that there is only one individual trapped in a social network, and that there are only societies teeming with diverse individuals, like pieces of matter formed of atoms" (Moscovici, 1984, p. 5). The author also points out that in each individual there is a society with its dreamed characters, its heroes, friends and enemies, parents, and siblings, with which each one maintains a permanent dialogue. This perspective allows us to understand that "[...] social psychology is a science of the conflict between the individual and society: [...] of the society outside and the society inside" (Moscovici, 1996, p. 6).

Social psychology thus conceived comprises social thinking, that which develops in everyday life, which formulates common sense and guides conduct. The social thought that manifests itself in the collective and is structured by opinions, attitudes, social representations, and ideology, as Rouquette (1996) points out, obeys a logical hierarchy among these elements: attitudes allow us to account for opinions; social representations, the founders of a culture, account for attitudes; however, it is the ideological components that allow us to produce representations (general beliefs, values, epistemic models).

In this sense, social representations, as founders of cultures, can be considered as a social environment, as a social atmosphere (Moscovici, 2003), which, thus, conventionalize objects, people, events and make it possible to share meanings in a collectivity that allows communication, besides making it possible to see only what the conventions allow us to see. The author also points out that, in this movement, representations are prescriptive. We are born immersed in a field of meanings and prescriptions that influence us in such a way that, when we build representations, we start to rethink these meanings and (re)present them in our daily relationships.

All classification systems, all images and all descriptions within a society, even scientific descriptions, imply a linking of previous systems and images, a layering in collective memory and a reproduction in language that invariably reflects previous knowledge and breaks the bonds of present information. (Moscovici, 2003, p. 37).

In this research, as we seek to understand the representations in the face of the covid-19 pandemic, we are also moving towards understanding the structure and process that constitute the social thinking of education professionals. The pandemic object of covid-19, a new object, started to demand from everyone the construction of representations that could account for the understanding of this strange object, which would allow communication and interaction among people, favoring the sharing of knowledge among peers or in the group.

What we are suggesting, then, is that people and groups, far from being passive receivers, think for themselves, produce, and ceaselessly communicate their own specific representations and solutions to the questions they themselves pose. [...] they formulate unofficial, "spontaneous philosophies" that have a decisive impact on their social relations, their choices, the way they educate their children, how they plan their future, etc. Events, sciences, and ideologies only provide them with "food for thought". (Moscovici, 2003, p. 45, emphasis added).

Based on this perspective, we analyze how the phenomenon of representations has generated, from the identity positions, the belonging, the values, the norms of the education system, the media communications, the educational context, in short, a common thought about the pandemic of covid-19, among women educators. Of the studies aimed at understanding this period in Education, we highlight the work of Saraiva, Travesini, and Lockmann (2020) who sought to examine remote teaching and teacher burnout. Although most of the research participants were elementary school teachers, there was no perspective by the authors to analyze women, whose focus was the interest in our research.

In the gender perspective, we highlight the study by Useche Aguirre et al. (2022), which sought to analyze the relationships between society and the covid-19 environment. These are studies of great interest, but they were not studies in social representations, they were not studies that analyzed the woman educator; thus, they did not have as an objective the understanding about the professionals who work in Education. In these terms, we believe that the research conducted offers the pedagogical possibility for the reader to reflect on the experience of teachers and pedagogical coordinators in the pandemic and to understand their actions in the school routine.

The research

The study was conducted with professors and pedagogical coordinators of the master’s course in a university in the city of São Paulo. In the methodological plan elaborated to give an understanding of the social representations of these professionals regarding the pandemic, we initially used the Free Word Association Technique, in which we asked them what words came to mind when the word "pandemic" was mentioned, and then how they justified them. The analysis of the evoked words and their justifications allows us to capture the "[...] discursive content that are expressed by a group in relation to a given object" (Moliner & Guimelli, 2015, p. 38.), in our case, the pandemic. Next, the participants were asked to describe "how was their experience with the pandemic in their professional life". The data production was done in two moments: in the beginning of 2020 and in the beginning of 2021, with 58 women1.

Regarding the ethical procedures related to the study, we emphasize that the Research Project and the documents necessary for the research were submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP)/National Research Ethics Commission (Conep) system. As Mainardes and Cury (2019) justify, it is necessary that

[...] all research involving human subjects must have as its founding principle the dignity of the human person [as well as] respect for participants, consent, careful assessment of potential risks to participants, commitment to the individual, social and collective benefit of research [...]. (Mainardes & Cury, 2019, p. 43).

Therefore, in the present research, we were careful with the "[...] respect for human rights and autonomy of will [...]", in addition to the commitment to the "[...] high standards of research, integrity, honesty, transparency and truth, [...] defense of democratic values, justice and equity [and the] social responsibility" (Mainardes & Cury, 2019, p. 43). Thus, with this ethical perspective, we obtained the consent and acceptance of the professionals in order to respect their integrity, so as not to generate any discomfort or social and emotional risk to the participants. In addition, the students were aware that neither their names nor the names of their institutions would be revealed in the study, thus making them comfortable to address problems that occurred there, without fear of reprisal2. With this ethical procedure, the research was conducted from the project to the interpretation, analysis, and dissemination of the results.

The data generated in both moments, by the Free Word Association Technique, were processed by the software Iramuteq3 (Ratinaud, 2009) and allowed the prototypical and similarity4 analysis. The processing of the initial data showed no differences between the two moments, which led us to gather them in a joint analysis. Complementing these analyses, we used the elaboration of context categories, which made it possible to reveal aspects of the situated experience of professional women in Education, through thematic analysis, of the microanalysis type (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

The data obtained from the participants' answers about "how was your experience with the pandemic in your professional life" were processed by the software Iramuteq (Ratinaud, 2009) and generated the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC), which allows "[...] a lexical analysis of the textual material, [and] offers contexts (lexical classes), characterized by a specific vocabulary and the segments of texts that share this vocabulary" (Camargo, & Justo, 2013, p. 515).

In the research process in which we turn to the analyses of social representations and teacher policies, these contribute to make more understandable the complex dynamics of the school in which processes of ruptures and expectations occur in relation to the definition of school practices that define the relationships in the classroom or outside it. They are, therefore, tensions between change and conservation, experienced by the school, by its actors, anchored in a network of representations of the past, present, and future (Ens, 2021).

First results

The initial analysis was performed based on data from the Free Word Association Technique (Table 1). By reading Table 1, we noticed that the words that make up the possible central nucleus5 and those of the first and second periphery are mostly of an affective nature. Although the central nucleus6 presents the word "tired", which indicates, in fact, symptoms of disease, we also find the words "concern", "family" and "sadness". The word "fear" draws attention because of the number of indications, although it appears in the first periphery, for not having been chosen as the most significant.

Table 1 Prototypical analysis based on the answers of the professionals participating in the research by using the Free Word Association Technique (2020, 2021)

| Elements of the Proble Core | Elements of the First Periphery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evoked Words | F ≥ 4,71 | OM < 2,95 | Evoked Words | F ≥ 4,71 | OM ≥ 2,95 |

| Tiredness | 10 | 2,5 | Fear | 31 | 3 |

| Sadness | 7 | 2,7 | Isolation | 17 | 3,2 |

| Family | 6 | 1,3 | Death | 14 | 3,1 |

| Worry | 6 | 2,8 | Insecurity | 8 | 3 |

| Illness | 8 | 3,2 | |||

| Overcoming | 6 | 3,2 | |||

| Longing | 5 | 4,2 | |||

| Contrast Zone Elements | Elements of the Second Perphery | ||||

| Evoked Words | F < 4,71 | OM < 2,95 | Evoked Words | F < 4,71 | OM ≥ 2,95 |

| Adaptation | 4 | 2 | Loneliness | 4 | 4,5 |

| Distance | 4 | 2,2 | Suffering | 3 | 3,7 |

| Health | 4 | 2,5 | Uncertainty | 3 | 3,7 |

| Uncertainty | 4 | 2,8 | Exhaustion | 3 | 4 |

| Vaccine | 4 | 1,2 | Virus | 3 | 4,3 |

| Challenge | 3 | 2,3 | Restriction | 2 | 4 |

| Reinvention | 3 | 1,7 | Agony | 2 | 4 |

| Life | 2 | 1,5 | Science | 2 | 3 |

| Carelessness | 2 | 1,5 | Crisis | 2 | 4,5 |

| Care | 2 | 1,5 | Anxiety | 2 | 3 |

| Stress | 2 | 2 | Challenge | 2 | 3 |

| Losses | 2 | 1,5 | Cleaning | 2 | 3,5 |

| Learning | 2 | 2,5 | Computer | 2 | 4 |

| Remote Learning | 2 | 4,5 | |||

| Resilience | 2 | 3,5 | |||

| Prison | 2 | 3,5 | |||

| Distance | 2 | 3,5 | |||

| Mask | 2 | 3 | |||

Source: The authors based on the processing of the answers of the women professionals, performed by the Iramuteq software (2021).

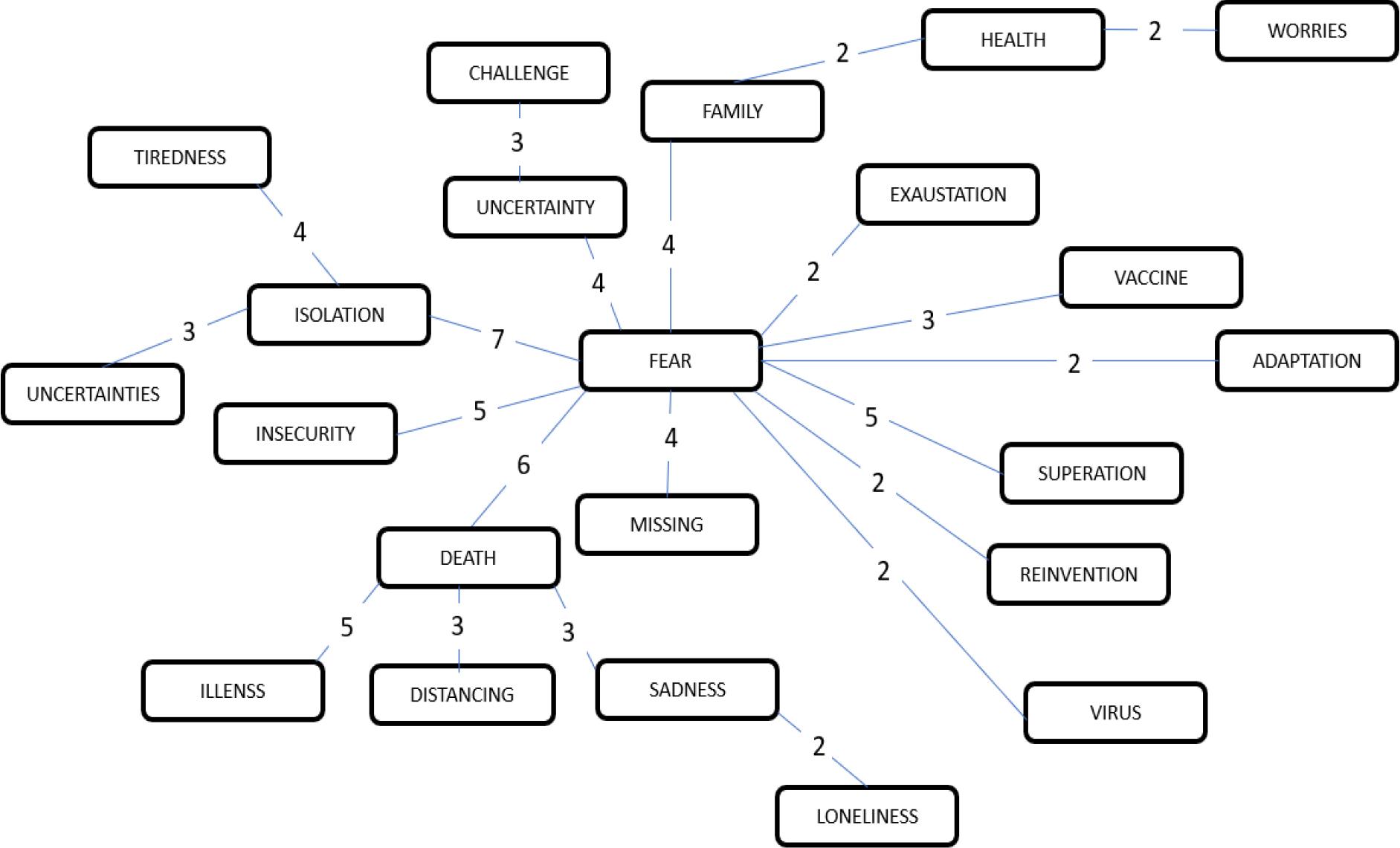

In this sense, as we can see in Figure 1, the similarity7 analysis puts as central the word "fear", which leads us to see that such word, in the year 2020, was more related to "isolation", "uncertainties", "tiredness" and "worries". However, the word "fear" in 2021 brings a deeper component, relating it to the word’s "death", "sadness", and "loneliness". Based on the concept of similarity analysis and on the thematic analysis of the content of the justifications of the choice of words, we deduce the arguments employed by the research participants.

Source: The authors based on the processing of the answers of the women professionals, performed by the Iramuteq software (2021).

Figure 1 Similarity analysis of the research participants' answers by using the Free Word Association Technique (2020, 2021)

About "fear", we deduce from Jodelet (2017), supported by the German philosopher Kurt Riezler (1944) - one of the first to approach fear based on a psychosociological point of view - that, in moments of crisis, "[...] a specific fear takes hold of individuals, 'the fear of the unknown' [as well as] the relationship between 'fear' and 'knowledge' at individual and collective levels" (Jodelet, 2017, p. 453). We corroborate with Jodelet (2017) that "fear," which almost completely took over the group of female teachers participating in this research, was "[...] situated between anxiety, fear, and dread" (Jodelet, 2017, p. 454).

Between social representations, experience with the pandemic and policies....

The choice of conducting an analysis through the CHD of the narratives of education professionals about their experience in the pandemic period, 2020 and 2021, is in line with the participants' discourse about the work process in this period. As this period of professional life was established by policies that regulated the attributions of Education professionals, we deduce, as Ball, Maguire and Braun (2016, p. 14, emphasis added), "[...] that policy 'formulation' is a process of understanding and translation [...]. However, policymaking, or rather acting, is much more subtle and sometimes more incipient than the pure binary of decoding and recoding indicates."

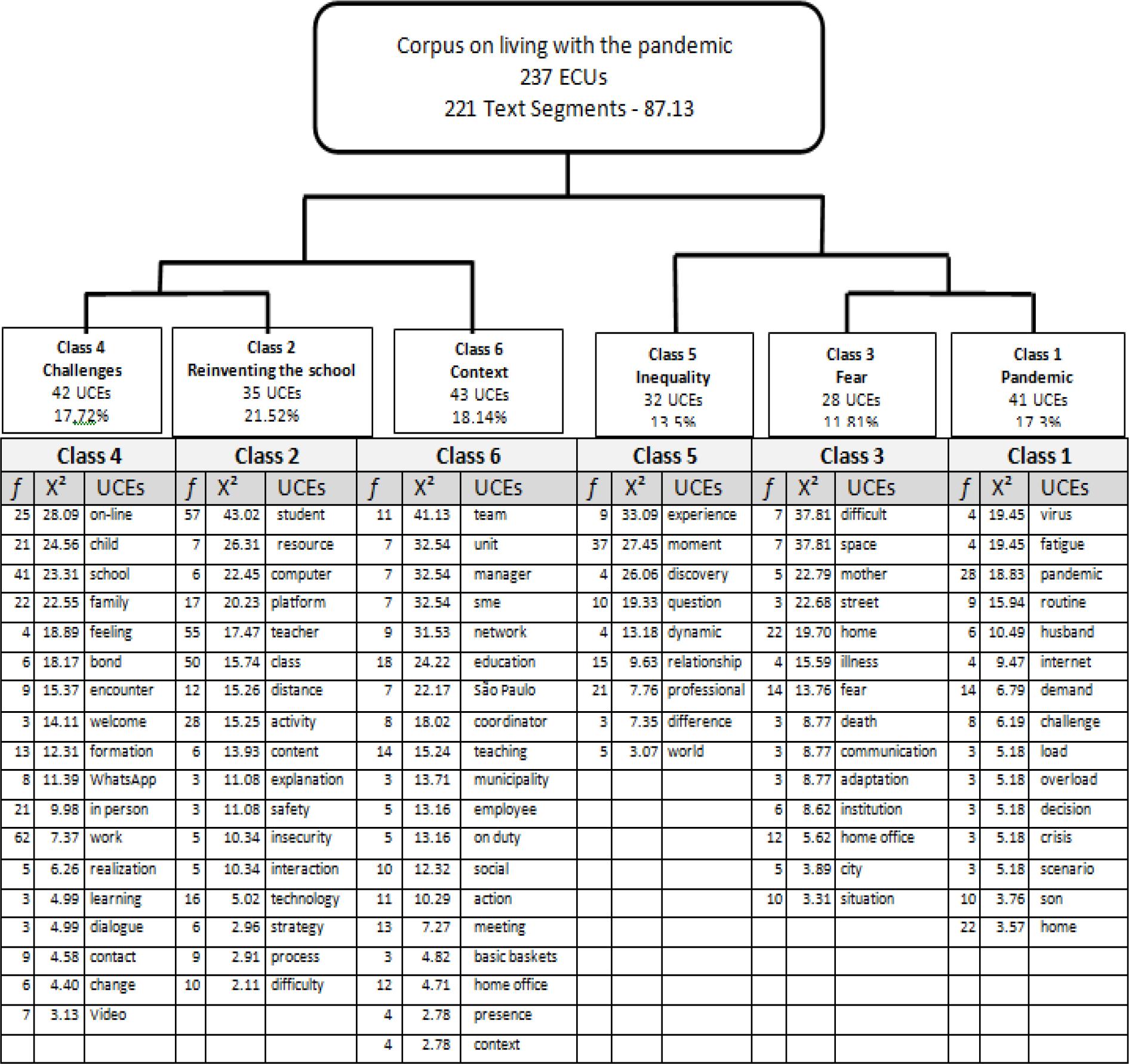

For this analysis, we chose to work with the different work spaces and the context in which the professionals were inserted, with the CHD8 , which resulted in the corpus, formed by the Initial Context Units (ICUs - 58 narratives of professional women), divided into 237 Text Units/Elementary Context Units (ECUs), of which 221 units of text segments were used for the construction of six thematic classes, which formed two groups of meaning (A and B). Thus, we can observe that there was a high utilization (87.13% of the ECUs), which denotes an acceptable percentage, since only 12.87% of the ECUs differed from the other classifications (Figure 2).

From the dendrogram (Figure 2), we identify that the hierarchical structure of the thematic classes (defined by the six classes) is grouped into two nuclei of meaning (A and B). Core A, called "fear", gathers the lexicons of Class 5 (Inequality), and covers the lexicons related to Class 1 (Pandemic) and Class 3 (Fear). The core of meaning B, called "context", incorporates the lexicons of Class 6 (Context), and covers the lexicons of Class 2 (Reinventing the School) and Class 4 (Challenges).

Regarding the utilization of ECUs segments, Classes 2 (21.32%), 4 (17.72%) and 6 (18.14%) account for 57.78% of the analyzed corpus, a total of 113 (42 + 35 + 43) of the 221 segments of the texts classified by the software. The presence of a greater number of segments related to the narratives, which use the classes as agglutinating lexicons referring to the use of the objects of study on "Reinventing the School", namely those selected for the analyses of the research object "Context", "Reinventing the School" and "Challenges", denotes the decision of the professionals in defining "Context" as one of the elements that transversalizes their narratives in this pandemic moment, as indicated in Figure 2.

Block A consists of the aspects that show the emotional process that dominated the professionals participating in the research. According to their narratives, the moment demanded physical as well as psychological, pedagogical, and economic requirements, as we highlight below:

[...] at first, I confess it was a moment full of uncertainties; however, it was also and has been a period of great discoveries and learning, whether in the use of new technological tools, or in the way of planning meetings with teachers [on] virtual platforms. (P22).

[...] since March 19th, the institution where I work has organized itself so that the employees could do their work at home office. [...] at first, we were informed that the work would be done remotely. (P2).

[...] I cannot say that the pandemic proved to be a great hindrance to my work, but I am aware that my reality is quite different from that of other teaching colleagues (P8).

[...] in my professional life, I had to adapt to working at home and review my routine. (P9).

[...] I had to increase the speed of the Internet, because, as I was not at home much (before), it was not so necessary. (P10).

[I am a teacher coordinator of the pedagogical core of a board of education belonging to the Secretary of Education of the State of São Paulo, I follow the work and I am a trainer of 34 teacher coordinators of the initial years. [since the beginning of the pandemic, we have been teleworking following the resolutions, innovations, and transformations that public education in the state of São Paulo has been going through, and we could clearly see the social inequality of students and teachers. (P20).

[...] with the pandemic, I saw my professional and student life totally disorganized in less than a month. Specifically in my life as a teacher at elementary school initial series, with fifth grade students, I was challenged to reinvent myself. (P26).

Source: The authors based on the processing of the responses of the female professionals, performed by the Iramuteq software (2020-2021).

Note: For illustration purposes, the nouns with the strongest significant association for each class measured by chi-square (x2) were retained in the dendrogram.

Figure 2 Dendrogram - CHD with the respective nuclei of meaning formed by the thematic classes

In this sense, the policy regulated that schools and their professionals needed to develop their activities to meet the different contexts in which they operated, and with social skill, since they were in different groups that make up the school community. When analyzing Block B (Figure 2), we deduce that the policy was interpreted according to the context in which it needed to be put into practice, because "[...] policy is not 'made' at one point in time; [...] it is always a process of 'becoming', changing from outside in and inside out" (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, 2016, p. 15, emphasis added). In this way, it influences the construction of the professionals' representations about the experience of the pandemic moment. The influence of the context on social representations through the ideological field, according to Moscovici (2003, p. 380), makes the narratives of the professionals about the pandemic moment "[be], themselves, a critique of existing theories and practices."

However, there is a need to understand the relationships that exist between the conceptions about challenges in the school space for these professionals who have as regulator the educational policies for the pandemic moment. The performance of these professionals, in different contexts, is intertwined with the public policy for the moment, since, according to Moscovici (2003, p. 334), "[...] there are three elements - context, norms and purposes - that regulate the choice we make of one way of thinking in preference to another", as shown in the excerpts that follow:

[...] the beginning was overly complicated; I had the feeling of having lost my daily references. The change of routine in such an abrupt and unusual way made me lost in the first weeks of social isolation. (P11).

[...] just as I imagine that school will not be in my last book either, I found myself with the challenge of writing about this new hybrid and undefined language while I was submerged by this intense transformation, it was an incredibly special process. (P54).

[...] I didn't even know how to manage this tool, but the desire to see them and talk to them was greater. After this kickoff, we decided to start [and] continue with the classes through activities and even video classes, to try to guarantee the learning of our students. (P15).

[...] having to convince teachers who have worked for more than 20 years at the school that something that I didn't even know would work was going to work, it was tense every minute. (P16).

Based on the studies of the Theory of Social Representations, through the analysis of psychosocial processes, we perceived the main trends that guide the social life of professional women in education who participated in this research. We verified that its scope tangents new possibilities to apprehend "[...] what societies think of their ways of life, the meanings they give to their institutions and the images they share" (Moscovici, 2003, p. 173).

Through the tension between change and conservation, which (re)establishes looks about the past, present, and future, we have that the policies aimed at the pandemic period experienced by professionals result from "[...] a complex interweaving of multiple influences" (Tello, & Mainardes, 2015, p. 44), because they were built by various actors and interests, which express power struggles.

Based on this understanding, we found that the professionals' social representations take the teacher policies as one of the macro-regulators of their tensions in this pandemic period, an aspect that allows them to give meaning, significance, and resignification to this moment by indicating their ideas and representations according to the historical, political, and economic period in which their institutions and actors are inserted.

Thematic content analysis of the justifications and arguments of the participants

We understand that it is also necessary to understand how this group of women teachers responded to the feminine perspective according to the context to which they were submitted. In the perspective of social representations, especially from a Latin American approach, there is a political commitment to social transformation and, also, from the logic of everyday life, with the lives of people and social groups (Sousa, & Serrano, 2021). Therefore, we thought it useful to complement the analysis with the elaboration of context categories, revealing aspects of the situated experience of professional women in Education.

Methodologically, this required complementing the study with a thematic analysis. To this end, we worked directly with the material produced by the questionnaire, used in the first phase of the study, when they were asked to say what came to mind when the word pandemic was mentioned and how they justified them. The procedures consisted of performing a "line by line" analysis of the microanalysis type (Strauss, & Corbin, 1998), which was complemented by the systematization in a code matrix (Coding Chart) from which thematic areas of context were defined, according to the systematic proposed by Serrano (2010).

Through this procedure, eight context categories were found around the situated experience of these women professionals in Education when they answered the question related to the covid-19 pandemic, responses detailed in Figure 3.

Source: The authors based on the processing of the traditional thematic analysis of the responses of the female professionals (2020, 2021).

Figure 3 Analysis of context categories of the answers of the professional participants of the research by using the Traditional and Thematic Analysis Technique (2020, 2021)

The observation of the categories indicates that the reports show a general uncertainty that runs through daily life, which the pandemic, among its negative effects, makes unpredictable. These are routine aspects that, before, were taken for granted. Doubt becomes known certainty, and the difficulties go through personal, bodily, relational, family, work, and social aspects. There are intersectional and intercultural differences. The forms of relationship with the body, with the family, at work, and with communities have changed. It is debated whether scientific knowledge, which has been the pillar of certainties of modernity, has lost its validity here. The stances are polarized. There are those who believe that scientific knowledge (medical, epidemiological, virological, etc.) was not enough, while other positions point out that it was precisely scientific knowledge that allowed us information and timely tools to deal with the pandemic.

Fear goes hand in hand with doubt, uncertainty, and death, but there are many elements of meaning and experience in the data that point to a complementary yet separate category. It is also multiple and recurring fear, which is experienced individually, but elaborated socially, for the life and health of oneself and others, such as family members, colleagues, and compatriots. There is a manifest awareness on the part of the group of experiencing a situation of vulnerability, who fear the lack of structural conditions to develop life, but also fear for the lack of freedom. The mass media are pointed out as great propagators of fear and misinformation; and they are said to spread messages of "terror" (Jodelet, 2017).

Among education professionals, a generalized fear is formed regarding professional actions, of not teaching with quality in the new formats, of not being able to migrate to the online, hybrid model or even return to the classroom without health guidelines, in addition to losing their jobs or for their working conditions (low wages, loss of benefits, precariousness). Fear is linked to the institution, because, as it was narrated, it mobilizes discrimination, distancing, violence, and disrespect, but it is also from fear that people find the courage to follow and build alternatives for themselves and for others.

In relation to death, there is both fear for one's own death, but the death of someone from family and friends. They also comment on the importance of becoming aware and preparing for their own death and the death of others, because "[...] we are not prepared to deal with Death" (P70), although they delve into the contents that this category involves, such as sadness, for example. Sadness is reported for the experience of loss, grief and grieving processes, accumulation of losses together, and there is a component of indignation linked to the government's public handling of the pandemic, which will be presented in a separate category. "Death was what scared me the most during the whole pandemic, in seeing so many people dying, it made me very sad, disgusted, indignant in the most varied ways" (P21).

All participants speak of tiredness, exhaustion, tension, stress, overwork, and days that do not end (in three shifts and weekends), of incessant demands that are also accompanied by a fatigue that is physical, mental, and emotional. They comment that "[...] the teacher's work during the pandemic has been very stressful and sometimes cruel" (P51). They mention that the workday has tripled (between 12 and 17 hours a day), that they have never worked so hard, having to keep up to date, with too many online meetings (Zoomburnout) and technology platforms, having to change planning without guidance or resources. At the same time that the boundaries between home and office have been erased; it is difficult for them to establish boundaries between work and rest, as they cannot reconcile personal, family, and work schedules. They feel exploited and self-exploited, watched (the demands of management, administration, and bureaucratization of educational processes are increased with "forms and more forms"), vulnerable, alone, desperate, unmotivated, and unrecognized. Apparently, they accept these conditions because they are afraid of losing their jobs, or some have already lost them, because they have relatives and spouses unemployed, they have lost income, relationships, routines, certainties; there are colleagues on leave, sick and dead. They say that there is too much stimulus and little contact, too many exchanges and little communication, technological proximity but emotional distance at the same time, all connected but lonely, with few peers to talk to, no organization, having to be careful that what they say is not misunderstood. Mediating communications, supporting social and structural issues seems to have become more relevant than education itself. There is nostalgia in the classroom. All this involves physical symptoms, for example, when anxiety attacks, depression, tinnitus, insomnia, or asthma, a respiratory disease linked not to the SARS-CoV2 virus, but to the fact that the pandemic doesn't allow one to breathe, because it doesn't give one a moment's rest.

In the institutional and governmental spheres, there is strong criticism. There is talk of neglect, of failed public policies, of the importance of the school, and of powerlessness in the face of governmental actions and implemented public policies. There is a perception of institutional devaluation of the teacher, who is considered so little that he/she seems disposable and can be used as a "cannon fodder", as is the case of "[...] educational managers [for the fact that they were] forced to be on duty in the unit to take care of the patrimony. I felt disrespected and terrorized" (P7).

They reflect on the risks to the quality of education in terms of learning during the school year, age inequality profiles due to curriculum and teaching strategies (e.g., among young children), as well as differences among students, especially around equipment and access to the Internet and virtual classrooms. They discuss exclusion and dropout, the abandonment of children who no longer have school resources as an option, as the economic crisis has caused families to move in vicarious cycles of multiple vulnerabilities, and there is also a lack of resources to effectively exercise rights to access technologies and the internet network, which has hurt students.

There is a strong distinction between resources in private and public schools, with students who suffered multiple losses and those less affected, elements that indicate the need for and importance of further research on the impact of the pandemic on Education, over time and upon return to the classroom. As P48 explained:

Disappointing because in public schools we feel the bitter taste of exclusion and abandonment by the government; we feel impotent in the face of the impossibility of maintaining contact with economically less favored students who have many difficulties in online access, in addition to family situations such as unemployment, which is forcing many families to move to more peripheral neighborhoods, more distant from our reach. This situation will generate an immeasurable prejudice in an educational process that we do not know for sure if it will be possible to reverse it.

By reading the justifications and the moment experienced, we can see that the subjects made several critical comments made by the President of the Republic, which influenced the representations of the professionals, since he not only minimizes the pandemic, but also has no empathy with people's pain and satirizes the pain and loss from the height of his position of privilege, as stated by P30:

[...] what makes me most anxious is to see such a dictator president in our country, who ignores protective measures to fight the coronavirus, who produces fake news about the virus, who discredits science, who sets bad examples in the face of a global crisis due to the pandemic, who cares little about human life and who satirizes women. (P30).

Despite criticism of the government's handling of the pandemic, it is precisely impotence and anger that allow us to speak of resistance, since the "[...] pandemic accompanied by the extreme right of this Brazil that evaluates our aptitude for survival" (P25). For this, structural dismantling and genocide were faced as a form of resistance, since the "[...] vaccine is the way out to resume our lives a little, without the fear of dealing with death daily in view of a pandemic" (P58).

In the face of multiple challenges, there are varied learnings. The pandemic brought sudden changes, built a permanent learning curve, and also meant a valuable opportunity in the search for new strategies and resources. It brought changes in roles and responsibilities, in contexts, as well as new ways of appropriating Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), of educating and understanding teaching-learning, of generating dialogues that strengthen and feedback, of coordinating groups, of accompanying students, parents and teaching groups, of developing in teams, of inventing and learning. They reported that at least twice, at the beginning of the pandemic, there was a more surprising and chaotic moment, followed by a time when resources were being applied in pedagogical strategies. They also commented that they were managing to transform the methodology and the school learning experience beyond a multitude of disconnected activities that were prevalent in the beginning.

Hand in hand with learning, beyond fear and challenges, they talked about resilience, which they understood as a capacity to reinvent oneself, rebuild oneself, overcome oneself, revise oneself, start over, adapt oneself personally, in the family, at school, collectively, even on a planetary level. Thus, they become possibilities of "[...] overcoming and connecting with myself, with the group, and with the work" (P38). These alternatives were raised in the personal and professional, individual and group spheres, from a meta reflexive, systemic and playful dimension.

The pandemic made it possible to reconfigure personal and family projects, because "[...] we had to reinvent everything: home, work, study, relationships, distance, learning, pain, loss, death, joy, beauty, everything. And we keep on reinventing to deal with reality" (P54). In a collaborative and dialogical key, "[...] I cannot reinvent myself without counting on someone's collaboration" (P15). There are testimonies of participants who reevaluated their family and their life, recovered projects, got a master's degree, recalled their forgotten dreams, contributed to their multiple environments. Contact, exchanges, networking, problem solving were reevaluated and reconfigured, they spoke of having courage and strengthening hope in terms of life. "[...] after seven months of living with a pandemic I chose the word 'reinvention' because that is what I had to learn to do. To reinvent myself as a teacher, to adapt to new ways of communication and interaction to see life" (P26).

They emphasized that they encountered ethics of care in a cross-cutting way. However, they had somewhat polarized readings that were tied to the division of public-private spaces typical of early patriarchal modernity (Pateman, 1991). On the one hand, we find the traditional female care ethic, in which it is assumed that the core of women's lives is emotional, that their profession is secondary to their "domesticity," and that women are for others first (Lagarde, 1991), to which she becomes the sole and primary caregiver for others (children, spouse, elderly, relatives, parents) to the detriment of her health, her time, and her profession. "The most important thing is and certainly always will be my son and the fear of dying and not being able to see him grow up" (P26); "I am quite worried about this whole situation with the very high number of deaths. I fear for my family and friends" (P45); "My family is the word chosen as the most important, in time of pandemic, very afraid of my family members being affected by covid-19" (S2); "[...] my husband is out of work since the pandemic started" (P45). The problem was not the logic of care, they said, but that it was at their expense since the pandemic invaded their daily lives in a major way. However, because of the problems they faced on a daily basis, the women were the first to quit the online classrooms, unfortunately. They were not supported by colleagues or even family, as P32 explains: "[...] my family members don't see me as a professional, they interrupt me all the time, so family tasks, being a mother, consume me, delay the work, and compromise the quality. Fortunately, on the other hand, an alternative ethic of care has also been documented, which includes the logic and chains of mutual care and includes the ethic of male care. This is also part of the transformative potential documented in the pandemic. The logic of care, as distinct from the chains of care, are interdependent, collective, and not exclusively based on an overall excess burden of work - paid and domestic - on women.

The paradox of the pandemic is that, in order to survive individually, they had to take care of each other, which is why it becomes clear to these professional women

i) "being cared for" by family and friends, as participants 36 and 6 state "[...] at this time of the pandemic, even if we didn't even leave the house the friendship relationships became fundamental" (P36); "In this bad period, the closeness with the nuclear family was very important to sustain the other feelings" (P6);

ii) collective care, a care explained by P23: "[...] care, which was the first word that came to mind as soon as I finished reading the question. We experienced moments of care, care for the other, care for our elders, care for our children and for ourselves, in the face of this virus;

iii) male care and care of spouses and offspring, as alluded to by P45, P11 and P49: "[...] I had my son at home who demanded attention and the fact that my husband was not working helped at this moment, because he assumed most of the responsibility for taking care of the house and the son (P45)"; "[... ] the incorporation of household chores by all who live with me, children and husband, brought something very good, we spent more time together, we laughed, talked and complained" (P11); "[...] the pandemic caused the suspension of my work contract [...] the lack of income burdened my husband who needed to take sole responsibility for household bills" (P49);

iv) caring for life on a daily basis, as alluded to by participant P25: "All the feelings mentioned invade me, but sadness takes over my body and mind. Besides losing people, we passively watch misery take over our daily lives. I live in a house, and I have never seen so many beggars at my door as I see now.

All these aspects that transform the care for the respect and maintenance of life in the most important space/time of our daily lives.

v) care for the planet as humanity, stated P31, P55 and P40: "Because it is through contamination that all other situations occur" (P31); "[...] the rethinking of individual actions to rethink the collectivity and preservation of the species, besides giving a new meaning to daily life" (P55); "[...] all this situation that we are living at the moment must lead to a reflection on our way of life. It is the choices of meaning that humanity has been making that need to be rethought" (P40).

We deduce from the analysis of the eight context categories around the experience of these women professionals in Education, which denoted uncertainty, fear, death, government, resilience, learning, fatigue, and ethics of care, reveal, as Jodelet (2017, p. 470) states, "[...] the reactivity, reflexivity, and the capacities of invention to cope with transformations," of the world lived in the pandemic space/time.

Final Reflections

This text aimed to understand the social thinking before the pandemic, formed by groups of professional women in Education from the understanding of their social representations. Moreover, the study also allows us to state that the "[...] Theory of Social Representations develops at the crossroads of the scientific relevance of research and its social utility" (ROUQUETTE, 2010, p. 138), seeking to contribute both to the understanding of the world and the response to social demands in a context of widespread crisis.

It becomes visible, in this pandemic process, the interrelation of individual and collective dimensions in the elaboration of a social object, determined by social factors, as part of the architecture and functioning of social thought. As a result of the pandemic and despite being in "physical isolation", social exchanges shaped knowledge and practices and disseminated them in a more or less homogeneous way, as we observed in the case of Education professionals (Gruev-Vintila, & Rouquette, 2007).

Likewise, the role of affective experience and emotions in collective behavior was privileged, a domain less explored in the field of social representations (Campos, & Rouquette, 2003). In this, it is interesting and innovative to appreciate the process of evolution and deepening of the components associated with fear as part of social representations at the beginning of the pandemic and one year later. This responds to the practical experience with the pandemic that feedbacks knowledge and guides actions.

Covid-19 has become a "privileged setting", a "living social laboratory" to investigate social representations as processes. We distinguish the study of the emergence and change of social representations and the study of social representations made in this case of the pandemic by its enormous impact that everyday life allows. At the same time, we agree with Apostolidis, Santos, and Kalampalikis (2020) that the social representations perspective offers a unique paradigm to investigate covid-19 and that

[...] our reactions to the virus not only inform us of the risk of the virus, but also are a mirror of our systems of thought, our relationships, values, theories of the common world, and the principles that organize our social functioning. In this sense, covid-19 is a powerful revealer of individual and social realities. (p. 3.1).

Methodologically, it seems important to us to highlight the usefulness of triangulation in this case of a qualitative perspective in situated contexts, because making visible the interdependence between the individual and the collective, the dialectic between social life and action, in the fabric of individual, group and societal alternatives, allows us to recover the power of transformative action at the core of the Theory of Social Representations and its potential for micro empowerment, even in hegemonic situations. From the analysis of social representations, keys are found to reorient public policies and sustain structural change, since the theoretical perspective reinforces the importance of insisting on a broad understanding of the political, the polis, and the public space that necessarily recovers the agency of the individual and collective subjects to deal with social and civilizational crises.

1About the sample used, in the analysis of evocations for social representations, or prototypical analysis, according to Wachelke, Wolter and Matos (2016, p. 157), the "[...] results indicate that there is a considerable difference in the pattern of classification of elements as probably central or peripheral according to the sample size of the database associated with the prototypical analysis". In view of these considerations, the authors caution against performing prototypical analyses with small sample sizes. However, Wachelke, Wolter, and Matos (2016, p. 159) clarify: "Prototypical analysis should not be thought of as an inferential statistical analysis technique that needs a minimum sample size for its effective realization, but rather as a strategy that can be used to organize data more or less successfully, depending on its purpose," since this analysis "[...] is an exploratory technique used with convenience samples, but that allows for some diversity" (Wachelke, Wolter, & Matos, 2016, p. 159).

2The research is linked to a group of projects developed by master's students, doctoral students, and professors, focused on the study of the social representations of teachers from the theme "pandemic", submitted and approved by the CEP of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP).

3About the Iramuteq software, Salviati (2017, p. 4) highlights that "[...] it is a free open-source software, licensed by GNU GPL (v2), which uses the statistical environment of the R software. Like other open-source software, it can be changed and expanded using the Python language." Available at: www.python.org. Accessed on: 20 Sep. 2022.

4According to Camargo and Justo (2013, p. 516), this analysis "[...] is based on graph theory, makes it possible to identify the co-occurrences between words and its result brings indications of the connectedness between words, helping in the identification of the structure of a text corpus, also distinguishing the common parts and the specificities according to the illustrative (descriptive) variables identified in the analysis [...]".

5The peripheral elements, still based on Mazzatti's research (2002), are elements that make up the operative part of the representation. Their importance is given by the dialectical relationship between peripheral elements and the central nucleus. The contrast zone, on the other hand, shelters elements readily evoked by a minority subgroup, with high symbolic value, and for being in a process of transformation. In the future, it may come to constitute the possible central core or corroborate with the central core in the sense of complementing it (OLIVEIRA et al., 2005).

6 Mazzotti (2002, p. 20), based on the studies of Abric, states that "[...] every representation is organized around a central core that determines, at the same time, its meaning and its internal organization. This core is, in turn, determined by the nature of the represented object, by the type of relations that the group maintains with the object and by the system of values and social norms that constitute the ideological context of the group.

7It is a type of analysis, according to Flament (1981), that allows us to identify the co-occurrences between words, and, as a result, we have indications of the connectedness between words, which helped us to identify the common parts and the specifics from word matrices, organized in spreadsheets, as was the database built from the free word association test in this research.

8The CHD or Reinert method (1990) seeks to obtain text segments (ST), in which the results present vocabulary similar to each other and vocabulary different from the segments of the other classes. In the case of this research, by processing a group of texts about a particular theme (text corpus) gathered in a single text file that, from the processing by the Iramuteq software, of the ST and chi-square tests (x2) regroups the texts according to the similarity between them, partitioning the corpus into organized classes, in the form of a dendrogram that presents the relationships between the classes (Camargo, & Justo, 2018).

REFERENCES

ALVES-MAZZOTTI, A. J. A. A abordagem estrutural das representações sociais. Psicologia da Educação, São Paulo, n. 14-15, p. 17-38, 2002. [ Links ]

APOSTOLIDIS, T.; SANTOS, F.; KALAMPALIKIS, N. Society against COVID-19: challenges for the socio-genetic point of view of social representations. Papers on Social Representations, [s. l.], v. 29, n. 2, p. 3.1-3.14, 2020. [ Links ]

BALL, S. J.; MAGUIRE, M.; BRAUN, A. Como as escolas fazem as políticas: atuação em escolas secundárias. Tradução Janete Brindon. Ponta Grossa: Editora da UEPG, 2016. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, B. V.; JUSTO, A. M. IRAMUTEQ: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, Ribeirão Preto, v. 21, n. 2, p. 513-518, dez. 2013. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2013.2-16 [ Links ]

CAMARGO, B. V.; JUSTO, A. M. Tutorial para uso do software Iramuteq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires). Laboratório de Psicologia Social da Comunicação e Cognição. Florianópolis: UFSC, 21 nov. 2018. Disponível em: http://iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/tutoriel-portugais-22-11-2018. Acesso em: 5 out. 2022. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, P. H.; ROUQUETTE, M. L. Abordagem estrutural e componente afetivo das representações sociais. Psicologia: Reflexão e crítica, Porto Alegre, v. 13, n. 3, p. 435-445, 2003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722003000300003 [ Links ]

ENS, R. T. Possible dialogues between social representations and educational policies: the dilemma of data analysis. In: SOUSA, C. P. de; SERRANO, P. E. (ed.). Social Representations for the Anthropocene: Latin American Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021. p. 311-323. [ Links ]

FLAMENT, C. L’analyse de similitude: une technique pour les recherches sur les representations sociales. Cahiers de Psychologie Cognitive, [s. l.], n. 1, p. 375-395, 1981. [ Links ]

GRUEV-VINTILA, A.; ROUQUETTE, M. L. Social thinking about collective risk: How do risk-related practice and personal involvement impact its social representations? Journal of Risk Research, [s. l.], v. 10, n. 4, p. 555-581, 2007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870701338064 [ Links ]

JODELET, D. Representações Sociais e mundos de vida. Tradução Lilian Ulup. Curitiba: PUCPRess, 2017. [ Links ]

LAGARDE, M. Los cautiverios de las mujeres. Ciudad de México: UNAM, 1991. [ Links ]

MAINARDES, J.; CURY, C. R. J. Ética na pesquisa: princípios gerais. In: ANPED. Associação Nacional de Pesquisa em Pós-Graduação. (ed.). Ética e pesquisa em educação: subsídios. Rio de Janeiro: ANPED, 2019. p. 23-29. [ Links ]

MARCHAND, P.; RATINAUD, P. L’analyse de similitude appliqueé aux corpus textueles: les primaires socialistes pour l’election présidentielle française (septembre-octobre 2011). Actes des 11eme Journées internationales d’Analyse statistique des Données Textuelles - JADT, Liège, p. 687-699, 2012. Disponível em: http://lexicometrica.univ-paris3.fr/jadt/jadt2012/Communications/Marchand,%20Pascal%20et%20al.%20-%20L%27analyse%20de%20similitude%20appliquee%20aux%20corpus%20textuels.pdf. Acesso em: 27 set. 2022. [ Links ]

MOLINER, P.; GUIMELLI, C. Les représentations sociales: fondements historiques et développements récents. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 2015. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, S. La psychanalyse, son image et son public. Paris: PUF, 1961. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, S. (ed.). Psychologie sociale. Paris: PUF, 1984. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, S. Communications et représentations sociales paradoxales. In: ABRIC, J. C. (ed.). Exclusion sociale, insertion et prévention. Saint-Agne: Erès, 1996. p. 19-22. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, S. Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social. Tradução Pedrinho A. Guareschi. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2003. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, D. C. et al. Análise das evocações livres: uma técnica de análise estrutural das representações sociais. In: MOREIRA, A. S. P. et al. (ed.). Perspectivas teórico-metodológicas em representações sociais. João Pessoa: UFPB Editora Universitária, 2005. p. 573-603. [ Links ]

PATEMAN, C. The sexual contract. London: Polity Press, 1991. [ Links ]

RATINAUD, P. Uma evidência experimental do conceito de representação profissional através do estudo da representação do grupo ideal. Nuances: estudos sobre Educação, São Paulo, v. 16, n. 17, p. 135-150, jan./dez. 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14572/nuances.v16i17.325 [ Links ]

REINERT, M. ALCESTE, une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurélia de G. de Nerval. Bulletin de méthodologie sociologique, [s. l.], v. 26, p. 24-54, 1990. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/075910639002600103 [ Links ]

RIEZLER, K. The social psychologyof fear. The American Journal of Sociology, [s. l.], v. 49, n. 6, p. 489-498, 1944. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/219471 [ Links ]

ROUQUETTE, M. L. Représentations et idéologie. In: DESCHAMPS, J. C.; BEAUVOIS, J. L. (ed.). Des attitudes aux attributions. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 1996. p. 163-173. [ Links ]

ROUQUETTE, M. L. La teoría de las representaciones sociales hoy: esperanzas e impases en el último cuarto de siglo (1985-2009). Traducción Juana Juárez Romero. Polis: Investigación y Análisis Sociopolítico y Psicosocial, Ciudad de México, v. 6, n. 1, p. 133-140, 2010. [ Links ]

SALVIATI, M. E. Manual do Aplicativo Iramuteq (versão 0.7 Alpha 2 e R Versão 3.2.3). Planaltina, 2017. Disponível em: http://iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/anexo-manual-do-aplicativo-iramuteq-parmaria-elisabeth-salviati. Acesso em: 21 maio 2020. [ Links ]

SARAIVA, K.; TRAVERSINI, C.; LOCKMANN, K. A educação em tempos de COVID-19: ensino remoto e exaustão docente. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 15, p. 1-24, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.15.16289.094 [ Links ]

SERRANO, P. E. La construcción social y cultural de la maternidad en San Martin Tilcajete. Ciudad de México: UNAM, 2010. [ Links ]

SOUSA, C. P.; SERRANO, P. E. (ed.). Social representations for the anthropocene: Latin American Perspectives. Heidelberg: Springer, 2021. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, A.; CORBIN, J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1998. [ Links ]

TELLO, C.; MAINARDES, J. Políticas docentes na América Latina: entre o neoliberalismo e o pós-neoliberalismo. In: ENS, R. T.; VILLAS BÔAS, L.; BEHRENS, M. A. (org.). Espaços educacionais: das políticas docentes à profissionalização. Curitiba: PUCPRess, 2015. p. 31-62. [ Links ]

USECHE AGUIRRE, M. C. et al. Vinculación con la sociedad desde la perspectiva de género: un estudio en la universidad ecuatoriana. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 17, p. 1-21, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.17.19241.043 [ Links ]

WACHELKE, J.; WOLTER, R.; MATOS, F. R. Efeito do tamanho da amostra na análise de evocações para representações sociais. Liberabit, Lima, v. 22, n. 2, p. 153-160, 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2016.v22n2.03 [ Links ]

Received: August 21, 2022; Revised: September 26, 2022; Accepted: September 28, 2022; Published: October 10, 2022

text in

text in