Introduction

The term academic integrity can be defined as “Compliance with ethical and professional principles, standards, practices and consistent system of values, that serves as guidance for making decisions and taking actions in education, research and scholarship” (European Network for Academic Integrity, 2018). Despite the fact that research on this topic among university students has become widespread worldwide and the number of publications and studies on the subject has increased dramatically in the last two decades as it has been revealed in several literature reviews (Ali et al., 2021; Holden et al., 2021; Macfarlane et al., 2014), a notorious deficit of approximations and empirical evidence focused on academic integrity among graduate students still prevails, as evidenced by Gilmore et al. (2010). This fact may be due to multiple reasons, among them, the presumption of innocence that draws an image of the students who access the postgraduate level as a group with an acceptable degree of knowledge, skills and competences related to the principles and values of academic integrity (Chanock, 2008; Gilmore et al., 2010); however, the scarce existing research shows that this rather idealized vision of graduate students does not fit the reality (Schifter Caravello, 2008).

Universities have undergone important changes in recent decades, approximately since the last third of the 20th century, which have caused, among others, a significant increase in the number of university students in a context of decreasing funding for higher education, both in general terms and taking into account the expenditure per student (Fernández, 2018). This has led universities to try to capture the maximum possible income through postgraduate programs (where the percentage of public funding is lower than the level of undergraduate studies and the benefit of student enrollment for the institution is greater), thus turning the offer of postgraduate degrees into an international battlefield where universities try to reach a high market level (Altbach et al., 2009). At the same time, students reaching postgraduate stages are increasingly diverse and tend to view higher education as a means to improve professional opportunities (Bretag, 2013). In this context, understanding the dishonest behaviors of graduate students and calibrating their prevalence becomes a first-order tool to regulate and weigh the quality of the educational offer at this level.

In research work on academic integrity among students, four main areas or themes of study can be identified (Comas, 2009): the prevalence of dishonest behaviors, their severity, their causes and the potential solutions or corrective measures. This work focuses on the first two, which are normally investigated by (Comas, 2009): a) directly asking students, through qualitative or quantitative studies, what are the sources of social desirability problems in the responses and biases of the results associated with this phenomenon (Bernardi et al., 2012); b) collecting and analyzing data from plagiarism detection systems or data from third-party sources, which can generate other types of biases and problems in the validity of the findings (Foltynek et al., 2020); or finally, c) asking teachers or staff in educational institutions. The present study is based on this last sample typology, with the exception that we ask highly qualified informants who occupy positions of academic responsibility and management of postgraduate studies at Spanish universities (i.e. directors of postgraduate and doctoral offices, vice-rectors in charge of postgraduate studies, heads of postgraduate schools, etc.) and with the added value of also analyzing the perceived evolution of dishonest behavior over the past five years.

Among the existing literature on this subject, some contributions are highlighted, such as that of Ismail et al. (2011), who show that graduate students are often not prepared for the pressures and the degree of excellence that is demanded of them at this level of study and this can lead to malpractice in their training. Other works emphasize that graduate students are surrounded by numerous situational factors that can motivate them to commit dishonest actions during their studies, such as the pressure to publish large workloads in very short periods of time and a high expectation of autonomy and performance by supervisors or those responsible for their activities (Schmitt, 2011). The writing of graduate academic papers (essentially the Master’s Thesis and Doctoral Thesis) is one of the most demanding forms of academic communication and, at times, students face serious challenges to successfully complete these assignments, and in the face of these they engage in dishonorable practices that contravene the principles of academic honesty and probity. The main difficulties usually result from deficits in skills related to the writing process (Cahusac de Caux et al., 2017) or certain personal circumstances such as family and work commitments (Castelló et al., 2017).

Other factors that often cross the path of graduate students and that explain, in part, their dishonest practices are the feeling of loneliness and the lack of quality guidance and support from their thesis supervisors (Gardner & Doore, 2020; Pretorius et al., 2019). Another element that has an impact is the students’ perceived self-efficacy. Since these are highly autonomous learning processes, students who show low levels of perceived skills to complete the task tend to be more likely to seek shortcuts and unethical ways to fulfil their academic commitments (Huerta et al., 2017). Finally, a new possibility raised by studies such as Cutri et al. (2021) considers dishonest behavior among graduate students as a partial consequence of the impostor syndrome, in which some students perceive themselves as unworthy of their own achievements, despite there being objective evidence of the opposite (Clance & Imes, 1978).

This article aims to enrich and add to the existing body of evidence about academic dishonesty in graduate students, based on the opinions of a sample of academic heads of postgraduate studies from Spanish universities. To this end, the following research questions (RQ) are raised: RQ1) What are the most prevalent dishonest behaviors currently according to the postgraduate academic heads of Spanish universities? RQ2) What are the dishonest behaviors that have increased and decreased the most in recent years according to the academic heads of postgraduate studies in Spanish universities? RQ3) What are the most serious dishonest behaviors according to the academic heads of postgraduate studies in Spanish universities? RQ4) What level of agreement exists between the academic heads of postgraduate studies in Spanish universities regarding these issues?

Method

Sample

The study sample is constituted of 102 academic heads of postgraduate studies from 42 Spanish universities: 72.5% work in public universities and 27.5% work in private ones; 82.4% belong to traditional universities and 17.6% are employed in online teaching universities; 38.2% of those surveyed are women and 61.8% are men; the mean age of the sample is 51.5 years; 89.2% have a stable professional category (Full Professors and Associate Professors); 34.3% are from Social Sciences, 17.6% from Art and Humanities, 16.7% from Health Sciences, 15.7% from Sciences, and 15.7% from Engineering and Architecture. Regarding the years of postgraduate teaching experience, 8.8% have between one and three years, 21.6% have between four and ten years and 69.6% have more than ten years; further, 36.3% have between one and three years of experience in the position of academic head in postgraduate studies, 43.1% have between four and ten years, and 20.6% have more than ten years of experience.

The process to recruit the study participants was as follows: a) The names and contact information (email) of postgraduate programs academic heads were looked up on the websites of all Spanish universities (74) listed on the website of the Conference of Rectors of Spanish Universities (https://www.crue.org/universidades/); it was established that as a requirement to be considered academic head for postgraduate studies, the person had to occupy any of these positions: director or deputy director of schools/postgraduate centers, director or deputy director of schools/doctoral centers, vice-chancellor for postgraduate studies, and postgraduate academic secretaries. b) An initial list of 308 postgraduate academic heads was obtained. c) Each one was sent an email in November 2021 inviting them to answer the online questionnaire as well as an informed consent form that they had to fill out and sign before participating in the study. Up to three reminder emails were sent before closing the questionnaire application in February 2022. d) The response rate was 33.1%, which is a very significant percentage when compared with the reference indices of Kittleson (1997) and Sheehan and Hoy (1997).

Instrument and measurement

The questionnaire used was designed ad hoc for this research and contemplated 24 fraudulent/dishonest practices that graduate students may commit. These were compiled based on: a) the questionnaires used in previous studies by Henning et al. (2020) and Sureda-Negre et al. (2020); b) the validation of the questionnaire through the judgment of ten national experts in studies on academic integrity and social research methodology carried out during the months of September to October 2020; and c) a pilot test of the questionnaire administered to 12 former academic heads from three Spanish universities. The 24 dishonest practices that the study deals with are classified into: 1) practices related to exams and written tests (six items); 2) practices related to assignments (eight items); 3) fraudulent practices in general (six items); and 4) research-related practices (four items).

The questionnaire consisted of three blocks of questions on the prevalence, evolution, and severity of the 24 fraudulent/dishonest practices:

Prevalence: For each of the 24 practices, a response was required on a frequency scale, where: 1= Never/Infrequent; 2=Often; 3= Fairly/Very frequent.

Evolution: For each of the 24 practices, a response was required on a scale of evolution during the last five years, where: 1= It has reduced; 2= It has not changed; 3=It has increased.

Severity: For each of the 24 practices, a response was required on a severity scale, where: 1= No Serious/Little Serious; 2= Moderately serious; 3= 3 = Fairly/Very Serious.

Analysis

In the first place, the frequency tables of all the questions referring to the 24 fraudulent/dishonest behaviors (Prevalence, Evolution, and Severity) were analyzed in order to observe the distributions of the variables as well as the response category with the highest percentage for each of the 24 actions. Through this procedure it was possible to answer the questions: RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3.

Second, to answer RQ4, the percentage of agreement in each of the questions and the free-marginal Multirater Kappa of each action were calculated as a measure of the strength of agreement between those academic heads (Randolph, 2008; Warrens, 2010). The most frequent interpretations of the Kappa index are those of Fleiss (1981) (regular agreement between 0.40-0.60; good between 0.61-0.75; and excellent for values above 0.75) and Altman’s (1991) (poor agreement <0.20; weak between 0.21-0.40; moderate between 0.41-0.60; good between 0.61-0.80; and very good for values above 0.81). In this study, those with a Fleiss Kappa index greater than 0.40 were considered to be an acceptable consensus, which coincides with the Fleiss “regular” and Altman “moderate” categories. For data processing and analysis, the SPSS v.24 statistical software package was used.

Results

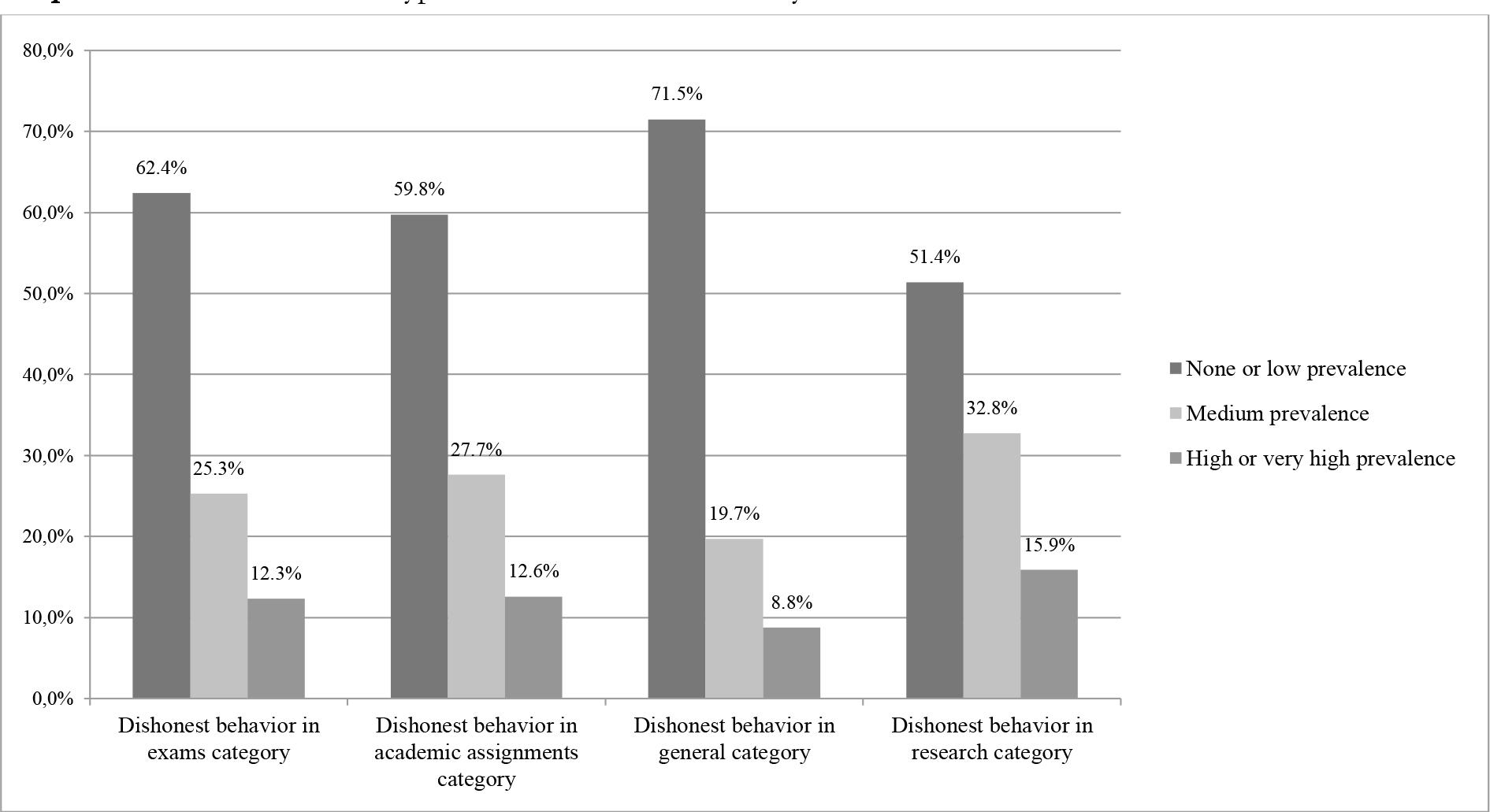

The study participants considered that the majority of dishonest actions they were asked about either do not occur or, if they do, are rare (see Table I). Regarding dishonest actions related to exams, those with the highest prevalence, in the opinion of the sample consulted, are: the use of technological devices to cheat, copying from a classmate, and allowing another student to copy. Among the dishonest actions related to the preparation and submission of academic works, the following stand out: plagiarism, presenting works downloaded from academic work exchange websites, and the inclusion of a student as an author in a work in which they have not really participated. In terms of dishonest actions of a general nature, the two that present higher levels of perceived prevalence are: using false excuses to justify a delay in a submission, attendance, or fulfillment of an academic obligation, and not reporting known cases of fraud committed by other students in evaluation processes. Finally, the dishonest actions related to research that present the highest prevalence are: the practice of salami slicing and the deliberate use of statistical procedures or data analysis that show more favorable results despite not being the most rigorous or suitable for the study conducted. When analyzing the data by blocks, the fact that three of the four dimensions provide very similar results stands out; thus, the block of improper conducts related to research is the one with the highest perceived prevalence (average 15.8% perceived fair or very frequent prevalence), followed by dishonest practices in the preparation of assignments (12.6%), and improper behaviors during exams (12.3%). Finally, dishonest behaviors of a general nature are those with the lowest perceived prevalence (8.7%).

The range obtained by the Kappa indices ranged between 0.01 and 0.91. In nine actions (37.5% of the total), an acceptable degree of agreement was reached among those responsible for the graduate schools who assessed the prevalence of dishonest actions. The highest degree of agreement was reached in the assessment of the prevalence of the following actions: “Impersonate the identity of another person in an evaluation test”, “Subtract/obtain the questions of an evaluation test before its application” and “Falsify official documents (language level certificates, grade certificates, diplomas, etc.) that allow the validation of an evaluation test”. The highest disagreement indices were reached in the assessment of the prevalence of the following actions: “Copying an assignment online using technological devices”, “Deliberately applying statistical analyses or data processing that show more favorable results for the investigation, despite these not being the most rigorous or adequate”, “Presenting an assignment work downloaded from an internet work repository”, “Copying an assignment from another student” and “Producing fragmented publications of the same work/study (salami slicing)”. By blocks, the average consensus index is higher in the dimension referring to dishonest behaviors of a general nature (66% consensus), with those related to the submission of academic papers and conduct during exams presenting levels of agreement of 54.1% and 52.1% respectively whilst research-related practices presented the lowest level of consensus (43.6%).

Table 1 Prevalence of the 24 dishonest/fraudulent behaviors

| BEHAVIORS | Nothing/ Infrequent | Often | Fairly/ Very frequent |

Overall agreement | Free-marginal kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREVALENCE of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to EXAMS | |||||

| 1. Using cheat sheets prepared ad hoc in exams. | 81.6% | 15.3% | 3.1% | 68.76% | 0.53 |

| 2. Copying assessable activities from unauthorized notes, books, or other material. | 57.7% | 28.9% | 13.4% | 42.87% | 0.14 |

| 3. Copying an assessable activity from another student. | 44.9% | 38.8% | 16.3% | 37.22% | 0.06 |

| 4. Students copying assessable activities among themselves. | 52.6% | 33.7% | 13.7% | 40.29% | 0.10 |

| 5. Copying an assignment online using technological devices. | 42.9% | 31.9% | 25.3% | 34.19% | 0.01 |

| 6. Subtracting/obtaining the questions of an evaluation test before its application. | 94.7% | 3.2% | 2.1% | 89.79% | 0.85 |

| PREVALENCE of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to ASSIGNMENTS | |||||

| 7. Presenting an assignment with verbatim copy of texts without citing their origin or with indirect citations (paraphrasing) without citing the sources. | 13% | 44.0% | 43% | 38.93% | 0.08 |

| 8. Excluding the name of a partner from an assignment they have, in fact, participated. | 91.6% | 6.3% | 2.1% | 84.14% | 0.76 |

| 9. Including the name of a partner in an assignment in which, in reality, they have not participated. | 43.2% | 43.2% | 13.7% | 38.48% | 0.08 |

| 10. Presenting an assignment that has already been evaluated in another subject or in another course. | 59.1% | 31.2% | 9.7% | 45.04% | 0.18 |

| 11. Presenting an assignment already carried out and submitted by another student. | 64.2% | 30.5% | 5.3% | 50.30% | 0.25 |

| 12. Presenting an assignment downloaded from an internet assignments repository (El Rincón del Vago, Monografias, etc.). | 41.9% | 41.9% | 16.1% | 37.10% | 0.06 |

| 13. Paying to have assignments made (Master’s Thesis / Doctoral Thesis). | 82.1% | 13.1% | 4.8% | 69.05% | 0.54 |

| 14. Producing assignments (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis) for another student and charging for it. | 82.9% | 11.0% | 6.1% | 69.98% | 0.55 |

| PREVALENCE of fraudulent/dishonest actions IN GENERAL. | |||||

| 15. Impersonating someone else on an assessment test. | 96.8% | 3.2% | 0% | 93.75% | 0.91 |

| 16. Presenting as your own an assignment produced by another person. | 71.7% | 18.5% | 9.8% | 55.35% | 0.33 |

| 17. Obtaining favorable treatment from administrative or academic staff to attain some personal benefit (for example: obtaining a research grant. better internships. etc.). | 86.5% | 11.2% | 2.2% | 75.89% | 0.64 |

| 18. Falsifying official documents (language level certificates. transcripts. diplomas. etc.) that allow validating an evaluation test. | 94.2% | 3.5% | 2.3% | 88.76% | 0.83 |

| 19. Not reporting to the lecturers or academic authorities known cases of fraud committed by other students in evaluation processes. | 48.5% | 39.2% | 12.4% | 41.09% | 0.12 |

| 20. Making excuses or finding false alibis to justify a delay in a submission, attendance or fulfillment of an academic obligation. | 31.3% | 42.7% | 26% | 41.67% | 0.13 |

| PREVALENCE of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to RESEARCH. | |||||

| 21. Duplicating publications or self-plagiarism in scientific publications. | 48.5% | 39.2% | 12.4% | 39.73% | 0.10 |

| 22. Producing fragmented publications of the same work/study (salami slicing). | 31% | 42.7% | 26,3% | 34.10% | 0.01 |

| 23. "Fabricating" or "making up" data in an investigation. | 78.7% | 14.6% | 6.7% | 64.04% | 0.46 |

| 24. Deliberately applying statistical analyses or data processing that show more favorable results for the investigation, despite these not being the most rigorous or adequate. | 47.1% | 34.5% | 18.4% | 36.75% | 0.05 |

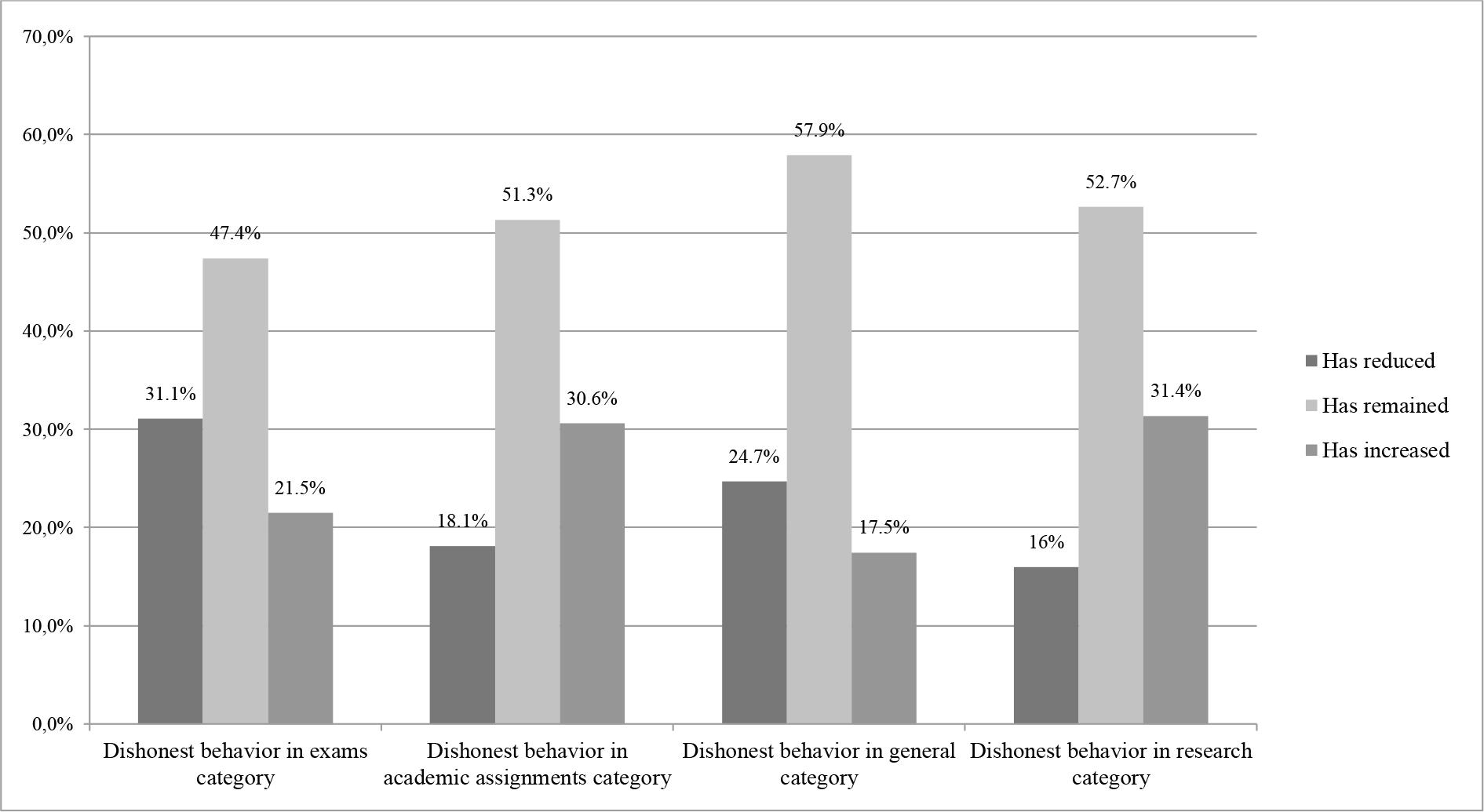

Regarding the second dimension of our study, the perceived evolution (reduction, stabilization or increase), there is the perception that in recent years, the dishonest behaviors of graduate students subjected to evaluation by the participants, has not changed substantially (see Table II). In the opinion of the academic heads of Spanish universities, in the last five years, only the frequency with which one of the considered dishonest practices occurs (using cheat sheets in exams) has reduced, while the frequency of another five would have increased (in decreasing order): copying by means of technological devices, plagiarism, presenting work downloaded from an internet repository, paying to have assignments made (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis), and producing assignments (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis) for another student and charging for it. Most of the dishonest actions that have increased in frequency in recent years, according to the evaluations carried out, are related to the submission of assignments.

If an analysis is performed by thematic blocks or dimensions (see graph 2), the perception of the participants is that behaviors related to dishonesty in research and in the preparation and submission of academic papers are the ones that have increased the most in the past five years (averages of 31.3% and 30.6%, respectively); the category that groups dishonest behaviors related to exams presents an average of 21.5 %, and the last position is occupied by the perception of increase in dishonest behaviors of a general nature (17.4%).

Finally, only in two of the dishonest behaviors studied (copying by means of technological devices and not reporting cases of academic dishonesty by graduate students) there was an acceptable level of agreement among the study participants. The Kappa indices obtained ranged between 0.04 and 0.50. With the exception of the agreement indices of the aforementioned behaviors, the consensus indices of the rest of the actions were not acceptable. When analyzing the data by blocks, two cases (dishonest behaviors of a general nature and dishonest behaviors on exams) showed consensus levels slightly above 50%, while the other two categories remained below this average.

Table 2 Evolution of the 24 fraudulent/dishonest behaviors

| BEHAVIORS | Nothing/ Infrequent |

Often | Fairly/ Very frequent |

Overall agreement | Free-marginal kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVOLUTION of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to EXAMS | |||||

| 1. Using cheat sheets prepared ad hoc in exams. | 55.8% | 40.7% | 3.5% | 47.22% | 0.21 |

| 2. Copying assessable activities from unauthorized notes, books, or other material. | 30.7% | 48.9% | 20.5% | 36.76% | 0.05 |

| 3. Copying an assessable activity from another student. | 25.8% | 65.2% | 9% | 49.39% | 0.24 |

| 4. Students copying assessable activities among themselves. | 25.3% | 70.1% | 4.6% | 55.25% | 0.33 |

| 5. Copying an assignment online using technological devices. | 9.8% | 11.0% | 79.3% | 64.56% | 0.47 |

| 6. Subtracting/obtaining the questions of an evaluation test before its application. | 39.2% | 48.6% | 12.2% | 53.50% | 0.30 |

| EVOLUTION of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to ASSIGNMENTS | |||||

| 7. Presenting an assignment with verbatim copy of texts without citing their origin or with indirect citations (paraphrasing) without citing the sources. | 11.2% | 33.7% | 55.1% | 42.37% | 0.14 |

| 8. Excluding the name of a partner from an assignment they have, in fact, participated. | 26% | 72.7% | 1.3% | 59.13% | 0.39 |

| 9. Including the name of a partner in an assignment in which, in reality, they have not participated. | 16.5% | 71.8% | 11.8% | 55.07% | 0.33 |

| 10. Presenting an assignment that has already been evaluated in another subject or in another course. | 22.2% | 63% | 14.8% | 46.11% | 0.19 |

| 11. Presenting an assignment already carried out and submitted by another student. | 21.0% | 61.7% | 17.3% | 44.81% | 0.17 |

| 12. Presenting an assignment downloaded from an internet assignments repository (El Rincón del Vago, Monografias, etc.). | 17.1% | 34.1% | 48.8% | 37.61% | 0.06 |

| 13. Paying to have assignments made (Master’s Thesis / Doctoral Thesis). | 16.4% | 32.9% | 50.7% | 38.36% | 0.08 |

| 14. Producing assignments (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis) for another student and charging for it. | 14.5% | 40.6% | 44.9% | 37.85% | 0.07 |

| EVOLUTION of fraudulent/dishonest actions IN GENERAL. | |||||

| 15. Impersonating someone else on an assessment test. | 39.2% | 48.6% | 12.2% | 39.69% | 0.10 |

| 16. Presenting as your own an assignment produced by another person. | 19.5% | 56.1% | 24.4% | 40.50% | 0.11 |

| 17. Obtaining favorable treatment from administrative or academic staff to attain some personal benefit (for example: obtaining a research grant. better internships. etc.). | 35.6% | 64.4% | 0% | 54.33% | 0.31 |

| 18. Falsifying official documents (language level certificates. transcripts. diplomas. etc.) that allow validating an evaluation test. | 11.2% | 33.7% | 55.1% | 54.12% | 0.31 |

| 19. Not reporting to the lecturers or academic authorities known cases of fraud committed by other students in evaluation processes. | 26.0% | 72.7% | 1.3% | 66.47% | 0.50 |

| 20. Making excuses or finding false alibis to justify a delay in a submission, attendance or fulfilment of an academic obligation. | 16.5% | 71.8% | 11.8% | 53.81% | 0.31 |

| PREVALENCE of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to RESEARCH. | |||||

| 21. Duplicating publications or self-plagiarism in scientific publications. | 21.7% | 46.7% | 31.5% | 35.81% | 0.04 |

| 22. Producing fragmented publications of the same work/study (salami slicing). | 13.5% | 44.9% | 41.6% | 38.61% | 0.08 |

| 23. "Fabricating" or "making up" data in an investigation. | 20% | 56.0% | 24% | 40.32% | 0.10 |

| 24. Deliberately applying statistical analyses or data processing that show more favorable results for the investigation, despite these not being the most rigorous or adequate. | 8.6% | 63% | 28.4% | 47.81% | 0.22 |

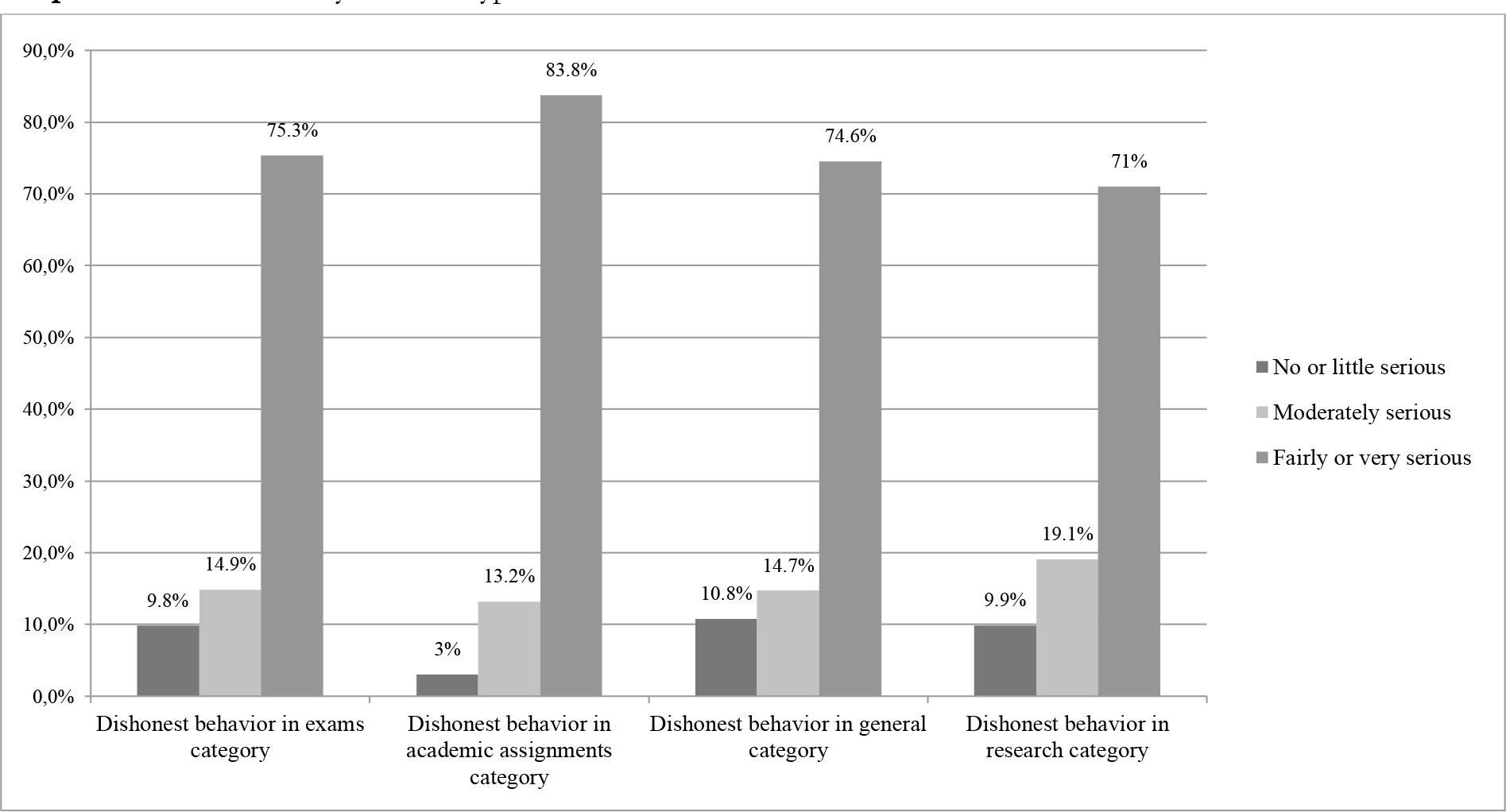

Regarding the assessment of the severity of the dishonest behaviors (Table III), practically all of them were considered serious or very serious. In this sense, “Falsifying official documents (language level certificates, transcripts, diplomas, etc.) that allow validating an evaluation test” and “Fabricating or making up data in an investigation” were the dishonest actions considered most serious by those academic heads who participated in the study.

None of the participants considered the following four actions as not serious or not very serious: “Producing assignments (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis) for another student and charging for it”, “Falsifying official documents (language level certificates, transcripts, diplomas, etc.)”,“Fabricating or making up data in an investigation” and “Deliberately applying statistical analyses or data processing that show more favorable results for the investigation, despite these not being the most rigorous or adequate”.

In the opinion of the participants, the less serious behaviors are (in descending order): making excuses or finding false alibis to justify a delay in a submission, attendance, or fulfillment of an academic obligation; allowing others to copy during an exam; and salami slicing. Analyzing by blocks of items, the highest perceived severity is related to dishonest behavior in the preparation of academic papers, followed by fraudulent actions in exams, and dishonest behaviors of a general nature; and lastly, research-related dishonest actions.

The degree of agreement between the study participants was acceptable in 15 of the 24 actions evaluated (62.5% of the total actions). The actions in which the lowest degrees of agreement were obtained were those considered serious or very serious by a smaller percentage of graduate school heads. The actions in which there was a greater degree of agreement in the evaluations made by the participants are also those that were considered as serious or very serious by most of them.

Analyzing by blocks, the highest degree of agreement is found in the perceived severity of the dishonest behaviors related to the preparation of academic papers (74% consensus), followed by dishonest behaviors of a general type (71% consensus) and finally, the others two dimensions show levels of agreement 10 points lower (62% of agreement).

Table 3 Severity of the 24 fraudulent/dishonest actions

| BEHAVIORS | Nothing/ Infrequent |

Often | Fairly/ Very frequent |

Overall agreement | Free-marginal kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEVERITY of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to EXAMS | |||||

| 1. Using cheat sheets prepared ad hoc in exams. | 11.5% | 17.7% | 70.8% | 54.14% | 0.31 |

| 2. Copying assessable activities from unauthorized notes, books, or other material. | 8.3% | 15.6% | 76% | 60.55% | 0.41 |

| 3. Copying an assessable activity from another student. | 6.2% | 22.7% | 71.1% | 55.67% | 0.34 |

| 4. Students copying assessable activities among themselves. | 29.5% | 22.1% | 48.4% | 36.35% | 0.05 |

| 5. Copying an assignment online using technological devices. | 2.2% | 11.1% | 86.7% | 76.13% | 0.64 |

| 6. Subtracting/obtaining the questions of an evaluation test before its application. | 1.1% | 0% | 98.9% | 91.50% | 0.87 |

| SEVERITY of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to ASSIGNMENTS | |||||

| 7. Presenting an assignment with verbatim copy of texts without citing their origin or with indirect citations (paraphrasing) without citing the sources. | 5.1% | 15.3% | 79.6% | 65.60% | 0.48 |

| 8. Excluding the name of a partner from an assignment they have, in fact, participated. | 1.1% | 13.2% | 85.7% | 74.95% | 0.62 |

| 9. Including the name of a partner in an assignment in which, in reality, they have not participated. | 5.3% | 28.4% | 66.3% | 51.83% | 0.28 |

| 10. Presenting an assignment that has already been evaluated in another subject or in another course. | 8.4% | 28.4% | 63.2% | 48.13% | 0.22 |

| 11. Presenting an assignment already carried out and submitted by another student. | 1.1% | 7.4% | 91.5% | 84.10% | 0.76 |

| 12. Presenting an assignment downloaded from an internet assignments repository (El Rincón del Vago, Monografias, etc.). | 2.1% | 8.5% | 89.4% | 80.42% | 0.71 |

| 13. Paying to have assignments made (Master’s Thesis / Doctoral Thesis). | 1.1% | 1.1% | 97.8% | 95.72% | 0.94 |

| 14. Producing assignments (Master’s Thesis/Doctoral Thesis) for another student and charging for it. | 0% | 3.2% | 96.8% | 93.69% | 0.91 |

| SEVERITY of fraudulent/dishonest actions IN GENERAL. | |||||

| 15. Impersonating someone else on an assessment test. | 1.1% | 0% | 98.9% | 97.78% | 0.97 |

| 16. Presenting as your own an assignment produced by another person. | 1.1% | 3.2% | 95.7% | 91.61% | 0.87 |

| 17. Obtaining favorable treatment from administrative or academic staff to attain some personal benefit (for example: obtaining a research grant. better internships. etc.). | 4.3% | 14.9% | 80.9% | 67.42% | 0.51 |

| 18. Falsifying official documents (language level certificates. transcripts. diplomas. etc.) that allow validating an evaluation test. | 0% | 0% | 100.0% | 100% | 1.00 |

| 19. Not reporting to the lecturers or academic authorities known cases of fraud committed by other students in evaluation processes. | 18.7% | 30.8% | 50.5% | 37.83% | 0.07 |

| 20. Making excuses or finding false alibis to justify a delay in a submission, attendance or fulfilment of an academic obligation. | 39.4% | 39.4% | 21.3% | 34.82% | 0.02 |

| SEVERITY of fraudulent/dishonest actions related to RESEARCH. | |||||

| 21. Duplicating publications or self-plagiarism in scientific publications. | 13.5% | 22.9% | 63.5% | 46.91% | 0.20 |

| 22. Producing fragmented publications of the same work/study (salami slicing). | 26% | 35.4% | 38.5% | 33.49% | 0.00 |

| 23. "Fabricating" or "making up" data in an investigation. | 0% | 2.1% | 97.9% | 95.79% | 0.94 |

| 24. Deliberately applying statistical analyses or data processing that show more favorable results for the investigation, despite these not being the most rigorous or adequate. | 0% | 16% | 84% | 72.89% | 0.59 |

Conclusions and discussion

The evidence provided by this study sheds light on the perception about academic integrity in postgraduate studies among the academic heads in Spanish universities, a “target group” that to date has not been used as a regular source of information in the studies on this subject. The vision and perception of this group is of utmost importance since, normally, their roles put them in a privileged position to design and implement corrective measures against dishonest behavior by students. Graduate students, researchers that are starting their career, play a crucial role in shaping future research and knowledge production environments and in fostering the credibility of science. The work, effort, and investment in the education and training of researchers from the beginning of their careers are essential means to promote and safeguard the integrity of future research (Fanelli et al., 2015; Krstić, 2015).

From the responses issued by the study participants, it can be inferred that the highest perceived prevalence of dishonest behavior among graduate students occurs in activities related to research and the preparation and submission of academic papers; both categories of dishonest actions are also the ones that have increased the most over the last five years in the opinion of those surveyed. Among the practices that the respondents perceive to have increased recently, special mention is made of payment to third parties for the production of academic papers or contract cheating, a practice that, according to numerous studies, is booming internationally (Newton, 2018). In general terms, the opposite occurs with dishonest actions related to exams, which have a lower perceived frequency and, at the same time, have decreased over the last few years; although in this category it should be remembered that there is one practice that has recently increased the most in the opinion of the study participants: the use of technological devices to cheat during exams. We understand this fact to be closely and logically related to the methodological and evaluation changes that have been introduced in the Spanish university system in order to homogenize it with the rest of the countries that share the European Higher Education Area. Among others, the implementation of the Bologna Process seeks to change master and directive teaching into a primarily practical and autonomous learning that manages to reduce the dependence of students on teachers. This aim is to be achieved through the development and promotion of learning strategies based on the organization, understanding, and synthesis of content; collaborative work; and the creation of reports, tasks, papers, and oral presentations of academic products as usual work tools for students and, at the same time, by reducing the weight of exams (López et al., 2010). In the specific case of the perceived increase in the use of technological devices to cheat in exams, we venture that it may be due, in part, to the time the questionnaire was administered, a period marked by COVID-19, and the implications of adapting the university systems to an online training and assessment model may have led to an increase in dishonest practices by students (Amzalag et al., 2021).

Regarding the question of the assessment of the severity made by the participants of the dishonest actions studied, generally, the seriousness they confer on most practices stands out, highlighting, above all, those related to the preparation of academic papers.

Finally, the results of this study allow us to develop a ranking of those practices that should be a priority for universities when undertaking corrective and preventive actions that guide institutional strategies and policies against academic dishonesty in postgraduate studies, if we attend to the opinion of academic heads. In order to establish this priority ranking, the response percentages of the most extreme categories of each block of questions (prevalence, evolution and severity) have been used, with the first five positions being, in decreasing order: the use of technological devices to cheat, plagiarism, the purchase of academic papers and theses, the falsification of official documents and the fabrication or falsification of data in research.

The results of this work can be used to address fraud and dishonesty in graduate degrees based on normative, awareness-raising, and training devices. We understand that it is necessary to introduce the issue of academic integrity on the agenda of Spanish universities in order to generate critical mass from which to design strategies, plans, and action measures. In our opinion, administrators and academic heads should be encouraged to examine their own institutional practices for factors that may contribute to student malpractice in an effort to develop training, awareness standards, and strategies to help prevent misconduct, which undermines integrity and the basic values of academic institutions.

text in

text in