Introduction

Non-biomedical research, especially that using methodologies typical of the humanities and social sciences (HSS), has been chiefly grounded on the epistemological pillars of qualitative research. As described by Diniz and Guerriero (2008, sup. 79), this type of research involves “(...) participant observation, ordinary observation, open or closed interviews, ethnography, self-ethnography and focus groups” and other methodologies. In the field of research involving human beings, the differentiation between biomedical and non-biomedical research occurs even in the definition of terms-research “inhuman beings” in biomedical areas, designating research that may be more invasive (although not always), and research “onhuman beings,” which has a more social character (De Oliveira, 2004).

Exploring the nature of these different approaches to research involving humans, we note that they reflect distinct scientific cultures and readings of ethical research, including readings and application of documents supporting the mainstream ethics regulation of human-subject research such as the Nuremberg Code (1947), the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), in its versions endorsed in Brazil, and the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2004) (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, 2013). For Guerriero (2016), the approach in the biomedical field is supported by practices and methods aligned with these guidelines and regulatory standards for research in humans in Brazil, based on the Resolutions of the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde - CNS), such as Resolution CNS 466/2012 (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, 2013). Thus, the norms resulting from this regulatory framework have a solid biomedical nature and are aligned with the particularities and research practices in this field of knowledge.

Regarding the ethical regulation of studies in non-biomedical fields that adopt methods typical of those in HSS, it is grounded on Resolution CNS 510/2016 (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, 2016). It assumes that “...the researcher-participant relationship is continuously built up in the process of the research, and can be redefined at any time in the dialog between subjectivities, implying reflexivity and the construction of non-hierarchical relationships...”, highlighting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the Inter-American Declaration of Human Rights and Duties as pillars that support the dignity, freedom, and autonomy of humans (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, 2016).

These distinct perspectives on the ethical regulation of research involving humans configure different research cultures with peculiarities in the epistemological and scientific domains. For “research culture” we mean “… the behaviours, values, expectations, attitudes and norms of our research communities. It influences researchers’ career paths and determines the way that research is conducted and communicated.” (The Royal Society, 2018).

In the context of research involving humans, there are cultural and epistemic “clashes” in the ethics review and research practices between biomedical and non-biomedical fields (Minayo, 2015), especially those associated with HSS. This conflictual situation reminds us of Charles Snow (1905-1980)’s “Two Cultures” (Snow, 1959), which has been applied to different epistemological and disciplinary battlefields.

The clash of two cultures in the conduct of human-subject research in Brazil

In “The Two Cultures”, Snow (1959) demonstrated the misunderstanding between two large groups, the literati and the scientists. As a physicist and a writer, he traversed these two environments and noted how different the ways of thinking were among the two groups; he even stated that they almost did not communicate at all, although he noted no significant differences among them regarding factors such as social origin or economic status (Snow, 1959). Regarding the distorted image of one group concerning the other, Snow (1959, p.4) describes the following scenario:

Literary intellectuals at one pole-at the other scientists, and as the most representative, the physical scientists. Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension-sometimes (particularly among the young) hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding. They have a curious distorted image of each other. Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can't find much common ground.

The appropriation of the “two cultures” embedded in Snow’s view (Snow, 1959) has been made in different academic contexts (Ciulla, 2019; Reynolds & Blackmore, 2013). In human-subject research, this perception of conflict is also evident when comparing research involving humans in the biomedical sciences and non-biomedical sciences, especially in HSS. Udo Krautwurst, in his “Culturing Bioscience; A Case Study in the Anthropology of Science” (2014), discusses the assumptions that inform the ethics review processes in the biosciences. The author (Krautwurst, 2014, p. 147) argues that there is a tacit assumption that “there is only one way to be ethical”, and that as “subjects of research”, humans are “equally powerless over what the researcher says or does. It is presumed that the research is necessarily on people rather than about people...”.

When it comes to research involving humans it is usually assumed that there is a power imbalance between the researcher and the participants, i.e., as the researcher would hold a position of power in this relationship, ethical concerns over this asymmetry becomes a sensitive issue (Råheim, 2016). Addressing this power dynamic is among the elements underpinning the work of research ethics committees, which are usually expected to protect the rights and dignity of research participants. Yet, some controversy over this role exists, and this idea of protection of research participants is another issue that Krautwurst (2014) explores. In ethnographic studies, for example, the assumption that research participants necessarily need to be protected by research ethics committees is among the sources of conflict (Krautwurst, 2014). Despite the lack of mutual understanding over the ethics of human-subject research in biomedical and non-biomedical fields, discussions on criteria for ethics review of HSS research protocols have put research ethics in the spotlight in Brazil.

Bridging “two cultures” of research on humans through a heated debate on ethics review

Notwithstanding the conflicts underlying the ethics review of human-subject research in biomedical and non-biomedical sciences (Mainardes, 2014; Duarte, 2017; Alves & Teixeira, 2020), these two cultures somewhat mingle in the CEP/CONEP System. Since its inception, this regulatory system has the premise of encompassing all areas of research involving humans - whether biomedical or non-biomedical. In the HSS academic community, researchers and scholars in education have been among the most sensitive to the issue of ethics in human-subject research (Brooks, Te Riele, Maguire, 2014; Mainardes, 2017). Mainardes (2017, p.167) writes that “in addition to concerns with the ethics review standards and procedures, it is considered essential to conceive research ethics as a training issue, which involves the study and discussion of research ethics at undergraduate and graduate levels…”. We believe the perceived importance that the role of ethics in research plays in the educational context has contributed to reflexive stances such as that by Mainardes (2017). The launch of a document entitled “Ethics and Research in Education: Subsidies Volume 1” by the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Education (ANPED) (Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação, 2019) reflects the attention on the big picture of research ethics. In this document, ANPED “reaffirms its commitment to the constant improvement of research in education and to the issue of research ethics” (Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação, 2019, p. 7), with contributions by various relevant authors addressing risks, consent, confidentiality, vulnerability, plagiarism, research with vulnerable populations, etc.

Guilhem & Novaes (2010) observe that notwithstanding the differences between the fields of social and biomedical research, there are similarities; for example, respect for the autonomy and dignity of people is a common central issue. Participants' free and informed consent is essential for research in both domains, differing only in the form of registration and, in some cases, time of obtaining consent.

Aligned with this observation, the view that research ethics is not and should not be restricted to concerns in the regulatory field echoes several authors. Grisotti (2015) cites the limitations of establishing this ethical debate based on submitting projects to the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) and thus reducing it to filling out forms on Plataforma Brasil. In fact, there needs to be more than this process to ensure responsible conduct in research. This thought is corroborated by authors such as Sobottka (2015), who argues that the type of social control laid out by the resolutions is that mediated by the CEPs. "As anex anteprocedural control (only projects and themselves are evaluated from the perspective of procedures), it is limited in its scope and, above all, in its reach" (Sobottka, 2015, p. 59). Brooks, Te Riele, & Maguire (2014), in "Ethics and Education Research", point to the relevance of ethical discussions in education based on real situations experienced by researchers.

Despite this sensitivity in the field of education, a study by Nunes (2017) has revealed the limited inclusion of research ethics in graduate programs in Brazil. This study analyzed 8,892 subjects in 37 education programs and found that only 0.78% (n=69) of them include research ethics in their course syllabus. Nunes (2017, p. 183) points to "the urgent need to guarantee disciplinary training and systematic on the topic of research ethics in graduate programs in Education". Mainardes (2017) highlights this gap as he emphasizes the need for more studies in the field of research ethics, an increase in the number of publications on procedures related to research ethics in HSS, translations of texts in foreign languages, and the need for a document with general guidelines on research ethics in conduct of research in education.

Given this context, the goal of this study was to shed light on perceptions of coordinators of graduate programs in HSS on the ethics review of human-subject research in Brazil. Specifically, we investigated perceptions about the ethics regulation of research involving humans through a survey instrument sent to 148 coordinators of graduate programs in HSS in public universities. We sought to explore the relationship they had established with the Brazilian national CEP/CONEP system, which has been implementing changes in recent years, impacting research in these areas. As part of a previous study (Rocha, 2020), the main hypothesis was that research practices for the ethical conduct of human-subject research in the biosciences in Brazil have established conversations with those in HSS studies. By engaging in the heated debate over ethics review, researchers in HSS have facilitated a reduction in the gap between these two cultures of conducting research involving humans.

Methods

Our research was based on a survey instrument sent to the coordinators of 148 graduate programs in HSS (n = 148). They were distributed among six universities - among the top 20 public universities in the national ranking (De Albuquerque Rocha & Vasconcelos, 2019) - in southeast Brazil, the region with the highest share of research funding and graduate programs in the country (Da Silva, Azevedo Filho & Da Hora, 2019): Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) (n = 32), Fluminense Federal University (UFF) (n = 21), State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) (n = 22), University of São Paulo (USP) (n = 50), State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) (n = 19), and Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) (n = 4). The protocol associated with this step was approved by the CEP at the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital (Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho - HUCFF), UFRJ - CAAE (Certificate of Ethics Review) 93926818.6.0000.5257.

The sampling was intentional and non-probabilistic. This type of sampling seeks to collect information from a particular group, intentionally selected and of vital importance to the research, with the potential of understanding the problem. Drawing upon previous studies (Bernard, 2001; Spradley, 1979; Cresswell & Plano Clark, 2011), Palinkas et al (2015, p.2) describe that purposeful sampling involves the identification and selection of people “especially knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest” and the importance to have “the ability to communicate experiences and opinions in an articulate, expressive, and reflective manner”.

The survey instrument, consisting of a demographic section with five questions and a content section with four questions, was prepared on the SurveyMonkey platform (https://pt.surveymonkey.com/) and then sent to the e-mail of the invited participants. The survey began on December 3, 2018, and the last response was received on January 7, 2019.

Among the issues of interest in this study were those exploring how the relationship with the CEP/CONEP System had occurred during the transition process, still underway, regarding Resolution CNS 510/2016. After the independent analysis of the corpus compiling the content of the responses, we drafted thematic categories, which we then refined in an iterative analytical process that led to our defining of four categories. As described by Duarte (2004, p. 222), thematic categories are “articulated to the central objectives of the research” as well as “to the theoretical/conceptual references that guide the view of the researcher”.

Results and Discussion

The survey of coordinators of graduate programs in HSS about the CEP/CONEP System explored their perceptions on aspects of the submission of research protocols for ethics review in their fields. With this survey, we also sought to understand the relationship of Resolution CNS 510/2016 with the setting investigated among participants.

Quantitative findings from the survey across HSS fields - interacting with and reading the CEP/CONEP System

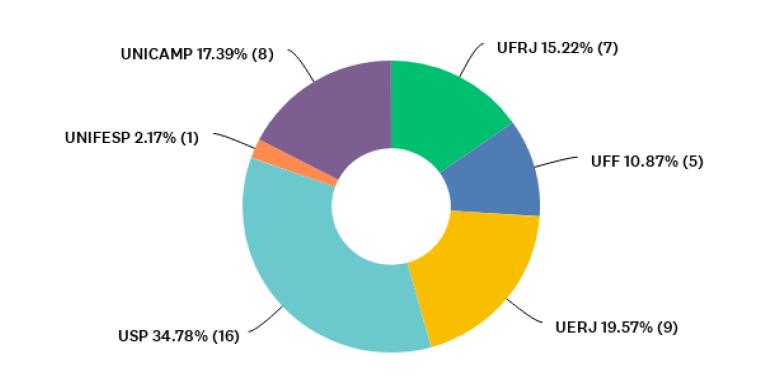

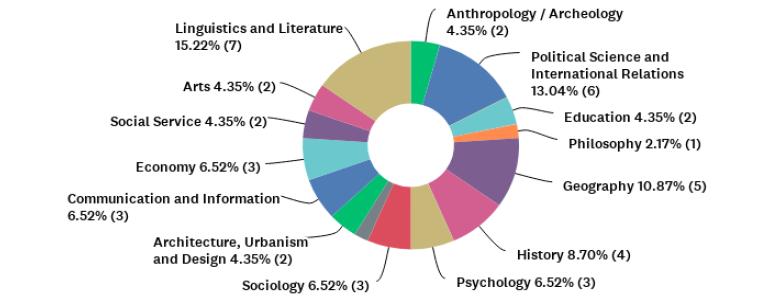

For an overview of participants’ institutions represented through their graduate programs, Figure 1 shows the percentages for each university, and Figure 2 shows the distribution of graduate programs’ main fields represented by the coordinators (n= 46), according to the assessment areas of CAPES. Most coordinators who participated in our research were serving their programs in this capacity for one to five years (n=31; 67%). Half of respondents declared that they had already served as coordinators or vice-coordinators before taking that position at the time of the survey.

Figure 1 Distribution of public (federal and state) universities represented by participants who responded to question P2 [The university of affiliation] (n= 46).

Figure 2 Distribution of graduate programs’ main fields represented by participants who responded to question P4 [CAPES Assessment Area of the graduate program of the coordinator] (n= 46), according to the assessment areas of CAPES.

Among respondents to question P7 [whether he/she or his/her supervisee had already had a research protocol submitted to the CEP/CONEP System] (n=46), 67% did not have submitted their research for ethics review by the national regulatory system. One speculation could be that neither these participants nor their supervisees conducted human-subject research. In our sample, only one coordinator alleged that no member of the graduate program had conducted human-subject research up to the time of the survey. Yet, it is unlikely that it was the case for most HSS programs in our study, given the nature of most research in HSS studies, which encompass human behavior, agency, mindsets, social and cultural processes, among other phenomena. Instead, this result is aligned with the status of human-subject research in HSS in Brazil, in which the ethical framework has not been traditionally relying on the ethics review by the CEP/CONEP System (Mainardes, 2014; Duarte, 2015; Alves & Teixeira, 2020).

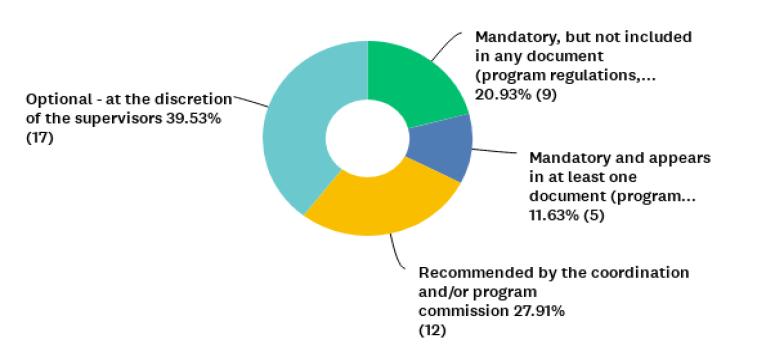

This observation echoes results shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Distribution of 43 graduate programs in humanities and social sciences represented by participants who responded to question P8 (n= 43), on the kind of normative guidance (if any) or recommendation they had for submission of research projects involving humans to the CEP/CONEP System.

When asked about the submission to the CEP/CONEP System of research projects involving humans in their graduate programs, including those using interviews and/or questionnaires (question P8), only 32% (n=14) declared that it was mandatory. However, 21% (n=9) of the respondents indicated “Mandatory, but not included in any document (program regulations, selection notice, defense requirements or others) of the graduate program”. Based on the self-reports of the coordinators surveyed, the absence of normative guidance in almost 90% of these HSS programs is prevalent. Despite this lack, it is interesting to note that 60% of coordinators indicate existing recommendations or requests in their Programs for submission to the System (Figure 3), which gives insight into the changes in the landscape for ethics in human-subject research in Brazil.

Qualitative findings from self-reports of participants

The qualitative results from the textual corpus based on the self-reports collected from the survey were organized into four thematic categories, as described in the Methods section:(1) aspects related to the Plataforma Brasil and bureaucracy; (2) view of the CEP/CONEP System; (3) familiarity with and/or position regarding the ethical regulation of HSS; and (4) regulatory aspects of the graduate programs.

On (1) aspects related to the Plataforma Brasil and bureaucracy, the bureaucratic nature of the process of ethics review is an issue in many countries (Martyn, 2003; McNeill, 2002; Bell & Wynn, 2020; Allen, 2023). In Brazil, researchers submitting research protocols to the CEP/CONEP System are also voices of complaints over the long material and/ or time involved in the submission process. In fact, such criticism is a common topic in biomedical and non-biomedical fields (Gusman, Rodrigues, Villela, 2016; Mainardes, 2017; Batista, 2017; Aliança Pesquisa Clínica Brasil, 2020).

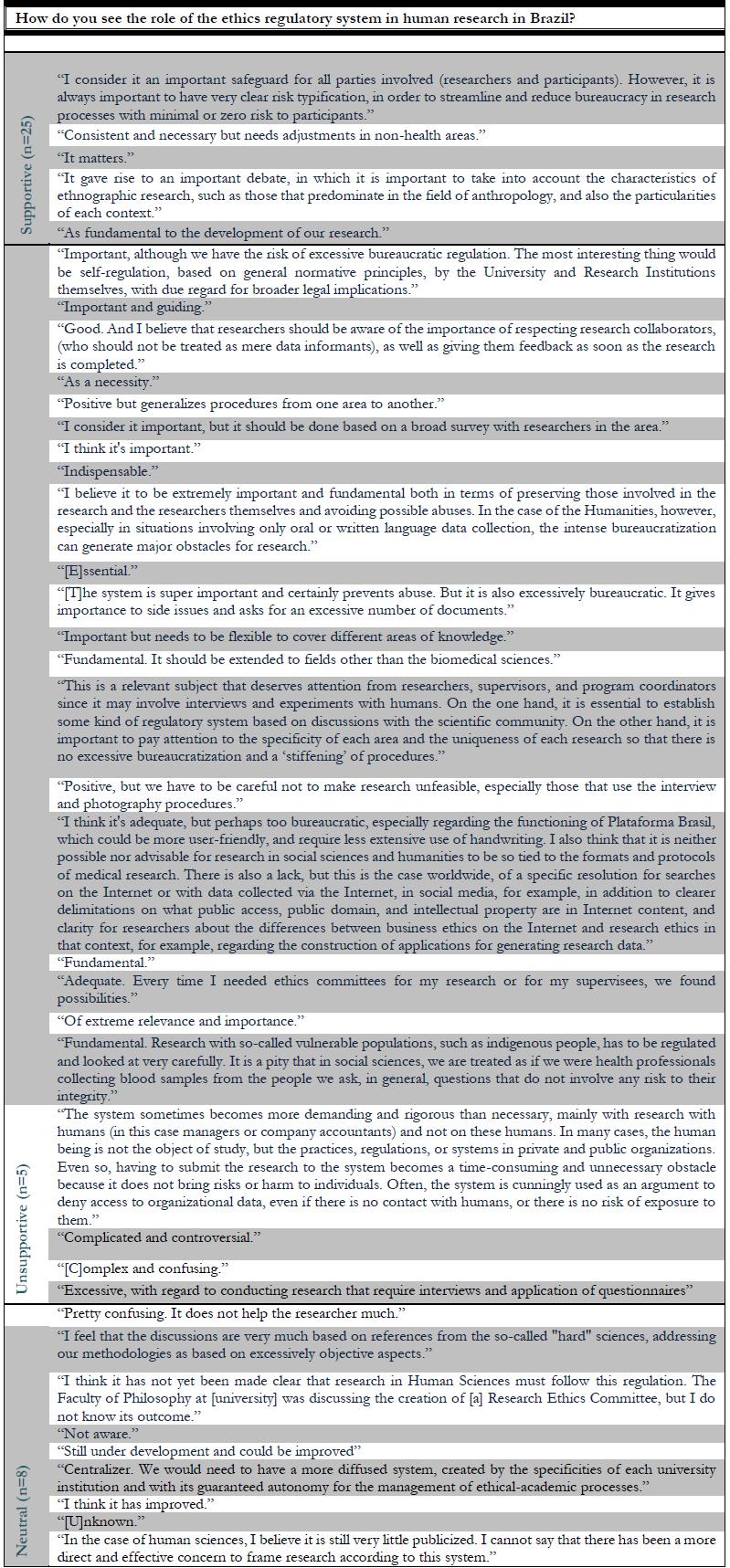

Among our respondents, excessive bureaucracy was mentioned by six coordinators (13% of the sample). One comment that illustrates this concern is from Respondent #21: “[T]he system is super important and certainly prevents abuse. But it is also excessively bureaucratic. It gives importance to side issues and asks for an excessive number of documents”. Overall, however, despite their criticism of several aspects, and based on their final comments (Box 1), the coordinators surveyed seemed to be more supportive of the System than unsupportive.

Box 1 ** Final comments of 38 respondents [coordinators of graduate programs in humanities and social sciences in Brazil] on the role of national regulatory system in Brazil for human-subject research.

Note that while bureaucracy is an issue raised by several coordinators, Respondent #47 reasoned that: [ethics review by the System is] “… an important safeguard for all parties involved (researchers and participants). However, it is always important to have very clear risk typification, in order to streamline and reduce bureaucracy in research processes with minimal or zero risk to participants.”

One factor that is consistent with a relatively new ethics regulatory framework for research involving humans in HSS in Brazil is that the (2) views of the CEP/CONEP System among the coordinators surveyed are not mature. Some of these respondents demonstrate that learning about the ethics review System is a gap to be filled. Respondent #39 states that “I think it has not yet been made clear that research in Human Sciences must follow this regulation. The Faculty of [field omitted] was discussing the creation of a Research Ethics Committee, but I don’t know about the outcome.”. This self-report is aligned with that from Respondent #2: “… Research with so-called vulnerable populations, such as indigenous people, has to be regulated and looked at very carefully. It is a pity that in social sciences, we are treated as if we were health professionals collecting blood samples from the people we ask, in general, questions that do not involve any risk to their integrity.”.

Accordingly, only some of the coordinators surveyed showed complete familiarity with or expressed a clear position on the CEP/CONEP System. Of the 14 respondents with comments associated withthematic category 3,“familiarity with and/or position regarding the ethical regulation of HSS”, eight indicated that they had begun to approach the CEP/CONEP System. This observation is demonstrated in the following statement byRespondent #38: “Although I was aware of the Resolution through indirect references, I had never read its content carefully, given the specificities of research in History. However, in practical terms, there was always a concern of the supervisors of the area with the ethical values in research involving living human beings or with direct descendants up to the third generation, such as Oral History (living deponents and informants) and research involving written documents or audiovisual records under public protection about recent History. However, as a program coordinator, this research caught my attention [motivating me] to more clearly formalize and standardize the specific issues in the field of History in terms of Research Ethics with and in humans. Thank you.”.

This recent encounter is also shown when, for example, it is declared that the CEP/CONEP System, though not unknown to researchers in HSS, is still distant from the reality of the research culture in their areas, as indicated by Respondent #19: “I’ve already heard of it, but I never studied it in depth”. In fact, approximately 30% of the respondents were unaware of Resolution CNS 510/16, suggesting that despite Resolution CNS 510/16 putting “the ethical debate on another level”, it takes time to consolidate a new resolution (Sarti, Pereira & Meinerz, 2017, p. 9). Other coordinators alleged that although the regulation was known in HSS, the research they developed had not approached “(...) more burning issues to be governed by the Resolution”, as Respondent #14 comments. For Respondent #10, knowledge of Resolution CNS 510 was eventually gained, once the coordinator became a member of the CEP. Otherwise, “(...) I would not have known, nor would I have sought to know.” For other coordinators, their knowledge of Resolution CNS 510/16 is “[o]nly in general terms” (Respondent #25); this lack of specific knowledge is also reflected in the comment of Respondent #39: “I was aware of the one [Resolution] for health research. I didn’t know about the [normative] demand for the humanities”. Respondent #42 wrote that “[o]nly now, in 2018/19, we will have the first research project submitted to the Ethics Committee in Human Sciences.”. These comments echo the results in Figure 3.

Previous data have shown a timid number of graduate programs in HSS recommending or requiring submission of research protocols to the ethics review by the CEP/CONEP System (De Albuquerque Rocha & Vasconcelos, 2019). The changing landscape, with growing awareness of the ethics review system among HSS researchers, may be understood in light of an analysis by Diniz & Guerriero (2008). The authors reasoned that “the imposition of the review system through research funding agencies, health institutions where data is collected or journals at the interface between biomedicine and the humanities…” motivated social researchers to “seriously address” research ethics (Diniz & Guerriero, 2008, sup. 80).

Finally, on the (4) regulatory aspects of the graduate programs, consistent with Figure 3, there were different situations about the submission of research protocols to the CEP/CONEP System. Some of the coordinators reported at the time of the survey that their universities were implementing requirements or beginning to consider developing them. Respondent #8 claimed that “We haven't included it as part of some normative guidance, but we consider this inclusion a mandatory step”. When it comes to normative guidance, Respondent #16 wrote that “[t]he rules at the university are changing and [submission to the System] will become mandatory and documented”. In line with these times of transition, Respondent #22 explained that when students enrolled in their graduate program, they had to acknowledge awareness of the obligation to submit human-subject research to ethics review, by signing a specific document.

Other coordinators reported that there was no recommendation, as can be seen in Figure 3. Respondent #26 is among the 21% (n=9) of respondents reporting that submission to the System was “Mandatory, but not included in any document (program regulations, selection notice, defense requirements or others) of the graduate program”, as also shown in Figure 3. This respondent reported that the program he/she coordinated did not deem it necessary to make such a recommendation in any specific document, as it was assumed that researchers were expected to follow the principles of the national regulatory framework [CEP/CONEP System] for the ethical conduct of human-subject research.

Overall, as can be seen in Box 1, a considerable number of respondents seem to be willing to get acquainted with, explore the possibilities of, and discuss research ethics in light of the ethics review process underway in Brazil. Whereas the challenges to address specificities and demands related to the ethics review of research involving humans in HSS remain, these coordinators surveyed suggest there is a promising space in HSS graduate programs to strengthen the role of research ethics in the design and conduct of research relying on human participation.

Final considerations

Our results indicate that some reluctance to interact with the Brazilian national regulatory framework for the ethics review of human-subject research in HSS is noted as a factor in our dataset. Nevertheless, according to our results, the majority of the HSS coordinators of the graduate programs surveyed is willing either to get acquainted with this regulatory system and/or exploring the ethics of conducting human-subject research in HSS. This finding comes from both the quantitative and qualitative data collected.

Whether this finding has been influenced by the affiliation of these HSS coordinators, with public universities in southeast Brazil, which accounts for the highest share of research ethics committees is an open question. Irrespective of this possible source of bias, the data suggests that these coordinators, representatives of their programs, seem to appreciate this regulatory framework at the reflexive and normative levels. Although bureaucracy is an issue that may discourage interaction with the CEP/CONEP System, most of the comments in the corpus pointed to willingness to take a step further and address the growing demand for addressing the ethics regulation of human-subject research in HSS fields. Yet, these are the views of coordinators and do not necessarily reflect those from the faculty members in their graduate programs.

Notwithstanding this caveat, according to these results, it seems reasonable to suggest that “two cultures” with their own scientific practices shaping research involving humans have been bridged by an ongoing debate over research ethics, which goes beyond the normative aspects of ethics review (Barros & Marcondes, 2019; Brooks, Riele, & Maguire, 2014). We believe the perceptions of these coordinators in HSS reinforce the need for broadening the look at the role of research ethics in conducting human-subject studies in the humanities and social sciences.

Limitations

This study is not immune to different kinds of biases, including social desirability bias, which is “the tendency to underreport socially undesirable attitudes and behaviors and to over report more desirable attributes” (Latkin et al, 2017, p. 2), leading to the possibility of inaccurate self-reports and thus unreliable conclusions in survey-based research. Looking “ethical” in research is scientifically and socially desirable, which makes investigations on perceptions of the ethics review challenging, irrespective of being related to human-subject research. Additionally, the hierarchical position of these coordinators in their graduate programs and burden of responsibility to take a position toward a highly sensitive issue in the HSS community might have led to more conservative responses. However, we sought to minimize these potential biases by the type of survey questions, more related to factual information than behavior, organized into a semi-structured instrument that offered space for participants to elaborate on their responses.