Introduction

This is the third introduction I have written for this paper. It seems to be writing itself backward. With each iteration I get to a point where I realize the frame has shifted and that a new context, or opening, is required. The shift of frame this time has arisen from my long teaching of an undergraduate world history course with a focus on Global Citizenship. The pedagogy for this course is enquiry based. In it questions are much more important than answers. The overall arc of the course is evolutionary. The key argument of the course is that there is a rich and deep Cosmic Story to be told! We humans have a part, but only a part, to play in this story which reaches back in time to the ‘Big Bang’ and will continue long after we have left the stage. This story is characterized by ‘stages of complexity’ (Chaisson, 2006). Each stage with characteristics unique to itself, and each stage informing following stages and the whole process offering maps that make sense of this process (Christian, 2004). As this course has unfolded over the years it has become increasingly clear that these maps are constantly being revised with new elements being added, other elements being adjusted or even discounted. Maps are living things. Offering narrative insights into the processes we human beings are embedded in.

This is where Neohumanism comes in. Just as Humanism offered a narrative map to explain and guide aspects of human social and intellectual development so too does Neohumanism. Both are propelled by the same logic of Relationship, of belonging to something greater than one’s self. There is one Human family, says Humanism. There is one Cosmic family, says Neohumanism. The difference is one of scale. What I am seeing today is that many voices, both activist, academic, spiritual, ecological and visionary, are converging around the insight that humanity is part of a living breathing system. That our Being, is premised on the Being of all around us. This is both exciting and mind boggling.

From an evolutionary point of view, we do not need to know where we are in this mix. But we do need ‘stories’ to help us manage the uncertainty that arises as this process accelerates. These stories are proliferating. There is an amazing Chorus of voices acting and speaking on behalf of the future. Activists are declaring that ‘we are nature defending itself’ (Fremeaux, 2021; Machado de Oliveira, 2021), academics are finding ways to make systems thinking and other processes of integration intelligible (and useful) (Bateson, 2016; Christian, 2018; Ison, 2017; Latour, 2017; Zaki, 2019), spiritual pragmatists are continuing the long tradition of challenging assumptions about reality and meaning (M. Bussey, and Mozzini-Alister, Camila, 2020; Giri, 2021), ecologists are pointing with insistence towards the natural intelligence all around us (Gagliano, 2018; Kimmerer, 2013; Simard, 2021), and visionaries are exploring through a wide range of media the possibilities available to - in fact contributing to - the futures before us (Hanh, 2021; Harjo, 2019; Morton, 2013; Neale, 2020; Salami, 2020; Yunkaporta, 2019). All is not doom and gloom here. We are being swept up in what the Indian visionary and coiner of the term ‘Neohumanism’, Prabhat Rainjan Sarkar decades ago called ‘an ideological tidal wave’ and such a wave affects ‘every dimension… every level’ of existence (1993b, p. 136). This is why, back in 2006 I made the somewhat audacious claim that we are at a Neohumanist Moment:

The conditions of late modernity have resulted in a convergence in history, environmental violence, economic injustice, political bankruptcy, resurgent religious fundamentalism, technological change and philosophical confusion. This moment places before us two possible routes into the future. The individual, every one of us, is faced with the choice between loss and alienation on the one hand (the future is an intensified and colonized extension of the present malaise) or a reclamation of self and spirit on the other (the future is an open and creative counter to present hubris). This convergence has created the conditions for the emergence of a neohumanist sensibility; we live at a moment in time that not just necessitates a deepening of human awareness but also validates it. (2006, pp. 39-40).

From a human perspective, the moment is arduous and agonizingly long, but from an historical perspective, a ‘moment’ can be measured in decades, centuries, even millennia. Moments are always potentially futures focused: they posit the question “What next?” This is no idle question. This is a challenge to contest dominant ‘business as usual’ narratives and explore alternatives. To broaden the question, we can ask: “What next for Humanity?” or even better, “What next for the Planet?” This is both a moment of opportunity and terror. Opportunity because the groundswell of possibilities has never been more sustaining; terror because the responsibility for wholesome, plausible and preferrable futures rests squarely with us.

My Compass

This special issue is an invitation to explore such questions. To scratch the surface of ‘What next?” I am attached to the term Neohumanism because it is part of my own intellectual and spiritual journey. It sits at the heart of my teaching and living. So it informs my own approach to the teaching of Global Citizenship. But is it a useful term? Or is it a single strand in the amazing chorus emerging at the moment? I think it is both useful and also just one strand amongst many. What is clear is that the Chorus is emphasizing the need for a human reorientation towards relational thinking, based on a love and respect for all life and for all that sustains life. So, I have acknowledged my own attachment to the term Neohumanism and also the deep connection I feel with the chorus of voices developing the field of innovative alternative narratives to a story of ‘decline and fall’.

In this paper I intend to situate my journey with Neohumanism as both one of becoming and also as an act of intellectual and spiritual inquiry. In doing so, as I note above, I situate Neohumanism within my own story as a teacher of global citizenship. I also situate this more broadly within my intellectual journey with Humanism. What emerges is that Neohumanism is a hybrid of East and West, the result of the intercultural encounters generated by global processes of integration (see, M. Bussey, 2018). The universalist aspirations of Humanism find their fulfilment within Neohumanism. And, furthermore, we find the critical richness of Humanism also extended through the relational logic of Neohumanism as we encounter the world directly through what can be termed: critical spirituality. Finally, I address the ‘cosmic agenda’ of Neohumanism suggesting that we need to rethink timing as the ‘human clock’ is limited. The ‘cosmic clock’ of evolution can allow us to rethink human action on behalf of the future. Roman Krznaric (2020) suggests we need to adopt ‘cathedral thinking’ as a part of the tool kit of good ancestry. I agree. Urgency is needed but paradoxically so is timelessness. Now I return to the story of how I was prepared for a Neohumanist adventure.

Roots and Routes

I have roots and have followed routes in this Neohumanist journey. My engagement with Neohumanism began with my work on the liberatory power of Humanism. I did my Honors thesis in 1980 exploring the thinking of Sebastian Castellio (1515-1563) who argued, against the dominant logic of the day, that doubt was an acceptable - in fact necessary - condition of intellectual and spiritual speculation. For Castellio “the better a man knows the truth, the less he is inclined to condemn”. And for Castellio this ‘truth’ was love. Love was the foundational principle of unity of the Church and characteristic of the true Christian. As a young student I found this insight compelling. Castellio linked love with reason and in this way prepared me for explorations in critical theory, Marxism more broadly, continental philosophy and education. When I discovered the work of Prabhat Rainjan Sarkar (1922-1990) with his focus on universalism and Neohumanism I was ready to ‘join the dots’.

What I recognised in Humanism was its profound ability to disrupt. Humanism was dangerous as it was a critical intellectual activity that contained the logic of relationship when assessing the value of human action. All humans where ultimately to be embraced as we shared the same humanity! From the 16th Century, humanist scholars were pushing the boundaries of European exceptionalism, with the Venetian Tommaso Giunti noting in 1563 that:

[…] it is clearly able to be understood that this entire earthly globe is marvelously inhabited, nor is there any part of it empty, neither by heat nor by cold deprived of inhabitants” (Headley, 1997, p. 3).

It took centuries, but the slow work of humanist reason would not allow for one category of human to exclude another. Thus planting the seeds of the human rights movements and ultimately leading to what Lynn Hunt (2007) has called a ‘rights cascade’. Castellio’s love was relational, humanist thinking saw humanity all over the globe and though much of it was not Christian, it was undeniably rich in the arts, technology, philosophy and more (see Graeber and Wengrow, 2021). The relational possibilities of humanism ultimately found its limit point in the human condition, the non-human or more-than-human was still excluded and subservient to the human project. And therefore, open to ruthless exploitation.

Intercultural Dialogue

Modernity brought with it waves of globalization. Culture shifted accordingly. Thinkers found much to fascinate them in the thinking of others. Graeber and Wengrow (2021) illustrate this beautifully in their description of European engagements with the indigenous philosophers of North America. This form of interaction went both ways. Human life is dialogical, or perhaps to avoid confusion it might be better to say ‘polylogical’. Elements of conversation, interaction, experience and ideation (the thinking that sustains us in our stories) are fractal. So it is that across the planet there is wave after wave of intercultural engagement. Thus we find in the work of the African American scholar bell hooks (2001) (lower case is intentional) a deep engagement between her birth faith of Christianity, with the critical force of Buddhism and the emancipatory power of critical theory. She makes a powerful case for ‘love’ in action and scholarship. Similarly, the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Han (2021) exemplifies the interaction between his Eastern roots and his route through Western thought, science and politics. For him thought and action are inseparable. “When we produce a thought, it is energy, it is action, and it can change us and change the world […]” (2021, p.40).

Similarly, Sarkar explicitly wove together an indigenous Indian Tantra with the Western tradition of Humanism. From the mid-1950s he began synthesizing elements of Indian Tantric philosophy with the European tradition of Humanism, at first in the form of Universalism, but he did not exclude the non-human from his thinking (M. Bussey, 1998). Tantra has deep roots in the Indian subcontinent. In Sarkar’s hands it offers a philosophy of mind that is layered (physical. Intellectual, subtle and spiritual) with a commitment to action that transforms the socio-economic foundations of society (M. Bussey, 2010; Hatley & Studies, 2016; Sarkar, 1993a, 1993b). Humanism, as an historical intellectual movement, had reached a limit in its anthropocentricism. The logic of Humanism was sound, but the focus needed renewing, expanding. He argued that universalism, seeing the entire Cosmos as an expression of numinous consciousness, challenged humanism to open its heart to the more-than-human. This idea crystallized in 1982 in Sarkar’s formulation of Neohumanism as a philosophy of relationship that could deal with issues of social and environmental justice (Sarkar, 1982). The logic at work in this reformulation assessed human activity according to whether it is ‘conducive to human welfare, [and] for the benefit of all beings, for the spiritual well-being of all” (Sarkar, 1982, pp. 74-75).

Universalism

It is revolutionary to bring in the spiritual, as a necessary aspect of Universalism. In Neohumanism the principle of ‘love’ takes on a Cosmic dimension, in which love is both beginning and end of the cosmological process. Love is relational, it offers us a spiritual pragmatics in which, as noted in the previous quotation, the benefit of the greatest number of beings is the metric for assessing its relational value. The ground swell of a spiritual pragmatism is an emergent element of current social and environmental justice, it is also decidedly post-colonial and inter-civilizational (M. Bussey, 2021). One element of this shift is a move away from the material as the ultimate ground upon which we stand. The material is always read through culture and consciousness. Neohumanist consciousness understands reality as a co-created open-ended process of becoming. Human culture plays a large part in determining this (from our perspective) but it is not the only, nor necessarily the most important, player in this process. Much of what we take as ‘reality’ is mysterious. And this is the way it should be. It is mystery that makes life so interesting (M. Bussey, and Sannum, Miriam, 2017).

Sarkar’s inter-civilizational approach makes him a creative traditionalist, reworking ancient Tantric philosophy for his generation. Creative traditionalism means we bring into the present elements of the past that allow us to navigate the present in a way that supports specific goals and values. There is ancient wisdom in the past. But there are also a lot of errors. Take caste for instance. This is harmful to humanity. Can we do better? I believe so. So creative traditionalism needs a compass, a value system and a set of tools that enables us to work from the past into the future in a way that enables optimal expression of people and also of the world (ie the non-human) we live in. To enable this Sarkar offered Neohumanism, stressing love, ethics and reason. He also taught meditation as a way to foster these. Neohumanism emerged from this mix as a powerful concept that bridged past and future by making the present both unique and also open to the loving intentions of us all (see Sarkar, 1997, p. 53). The futures before humanity become much richer in nature and cease to be closed or coopted by vested interests. This is exciting and it means we can critically engage the dominant assumptions of our day through a mix of benevolent mind and spiritual practice.

Critical Spirituality

In my own journey I found in Neohumanism a tool for spiritualizing what I found most rewarding in the project of critical theory and critical pedagogy. I found it to be a powerful form of critical spirituality (M. Bussey, 2000). In short Neohumanism augmented the critical engagement with our world. Neohumanism freed us a little more from the ordered and conditioned assumptions of reality and this, as Foucault reminds us, is the whole point of critique (Foucault, 2002). This freedom of course is always conditional. We cannot escape from the bounds of time, place and person. But critique can at least loosen the hold of context and make space for alternatives. Yuval Noah Harari (2015) describes reality as an ‘imagined order’. This concept captures the dimension of reality that is co-created by human interactions with the physical world along with the technologies and ideologies that we generate to help us navigate the present.

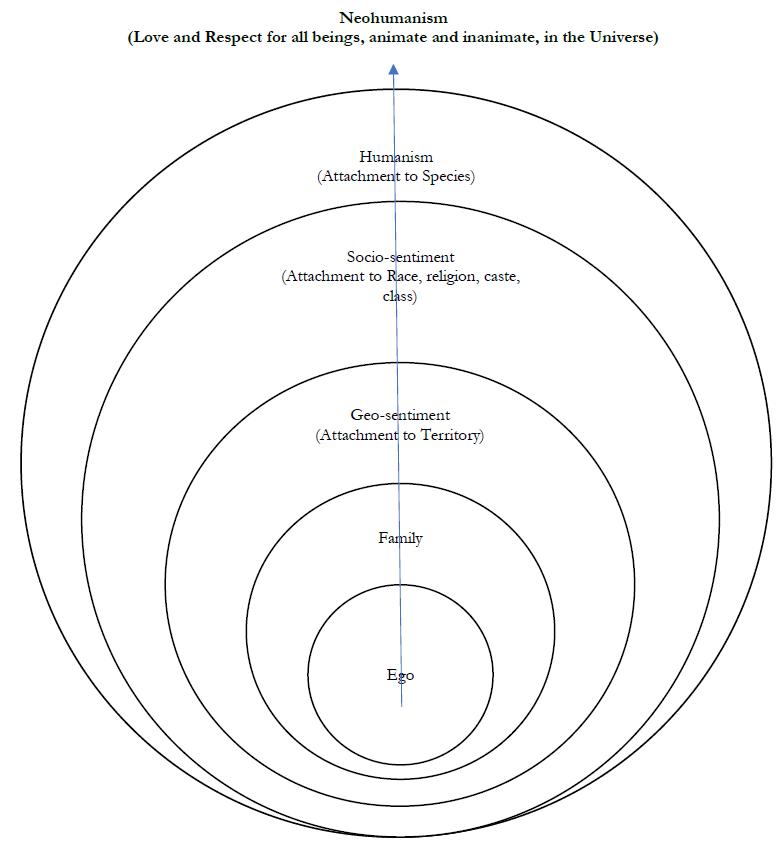

In Sarkar’s parlance, he would make a similar point calling reality an ‘ideological flow’ (Sarkar, 1997) in which human beings give form and force to their yearning for a return to the ‘Great’ (ibid, p.72ff). For Sarkar this is a spiritual yearning. But the yearning takes many forms: a yearning for power, or wealth, or meaning, or love. It is yearning which has spawned the worlds problems. It is also what will help us transcend these problems. The yearning itself is always there. It is what makes human beings restless. It also has a biological or evolutionary force what drives the creativity of the Universe. This yearning is futures focused and can be considered a futures sense (M. Bussey, 2017a). It is what drives us all ‘forward’, on to the next horizon. It takes the form of a creative restlessness of spirit. It is also what leads Neohumanism to challenge the limits of humanism. It is as if the Cosmos is asking of us: “Why limit the struggle for realization to the human?” And this brings us to the work of expanding human consciousness, ‘liberating’ it from conditioned reality. Neohumanism offers a ‘map’ for moving towards greater freedom. It helps us realize that we are part of an extraordinary process of escaping the trap of ‘culture’, as a human artifice that separates us from ‘nature’. Thus, when describing Neohumanism, Sarkar stated that as humanity moves from limited love to expanded love we move through attachment to ego, family, place, society, and species, and ultimately on to a sense of the Cosmic, or universal as the site in which we find the greatest freedom, meaning and purpose.

A Neohumanist Trajectory

Yearning to transcend, in response to a ‘longing for the Great’, drives the evolutionary trajectory of Neohumanism. Sarkar makes this point very clear, asserting “Each and every living being has got the longing for the Great” (1997, p. 72). This longing, as noted above, can take many forms from the material through to the spiritual. I read this as the need to challenge limits (M. Bussey, 2013). It is a critical project in which loving relationship acts as fuel and also Ananta Kumar Giri suggests the same. The critical project is an endless struggle for freedom from conditioning, from the oppression of any given present. And this struggle is at work across all fields of human existence: physical, economic, social, cultural, ecological and spiritual. Giri notes:

Life means multiple webs of relationships and criticism is an enquiry into the quality of these relationships. Criticism also seeks to understand whether the modes of togetherness suggested in life’s architecture of relationships genuinely holds together or not. Criticism begins with a description of the dynamics of relationships in life; observes and describes both coherence and incoherence, harmonies and contradictions at work in life; and seeks to move from incoherence to coherence, darkness to light, and from light to more light. An eternal desire to move from one summit of perfection to another is the objective of criticism, which is not a specialized attribute of life; it is life itself (2006, p. 2).

It is yearning, the ‘eternal desire’, that drives this quest. This can be understood, as in Image 1, as a Neohumanist arrow moving each of us from the entrapment of ego, through a range of sentiments for family, territory and social group to attachment to species and then into the Neohumanist realm of expanded being.

From Sarkar’s perspective the struggle to achieve the Neohumanist goal is eternal. It is part of the Cosmos’ own journey to return to a state of balance in which all elements of ‘being’ cease to cause the friction we associate with living. Life becomes as Giri notes, the critical project in itself. This struggle is the hallmark of life (Sarkar, 1993a, p. 32). It also offers us a teleology of sorts. As the physicist Michio Kaku notes, “the universe does have a point: to produce sentient creatures like us who can observe it so that it exists” (2005, p. 351). So at a meta level life has a point, well human life in the context Kaku is describing. We validate the universe through observing it. Yet all observation is partial. Think of the old Sufi story of the blind men and the elephants. As all culture is historical in nature, an accumulation of ingredients, the human ability to critique, to story, to imagine and act is always bounded. Those limits that I keep mentioning are always at work trying to tie us down whilst we keep trying to escape. What a paradox! The response Sarkar offers is the cultivation of benevolence through spiritual practice. Spiritual practice, properly understood as a combination of meditation with service and critique, ultimately yields ‘benevolence’ based on devotion to the Cosmos (1997, p. 96).

Humanism and Beyond

Let’s return to the Neohumanist Moment. From my perspective there is a ‘wave’, perhaps even a ‘tidal wave’, of activity pointing to humanity re-inventing itself. Has the energy of Humanism been spent? No, there is still much to be done to level the playing field for human beings. Intercultural action is feeding new and much more inclusive stories, yet the economics of distribution and extraction are still firmly maintaining disparity. Humanism is still a captive of its Eurocentric origins. In my teaching, I focus on the ‘global citizen’. Yet I spend much time on redefining the term ‘citizen’ (M. Bussey, 2015). I work to extricate it from association with the nation state. The nation state is the Humanist solution to the endemic wars of the 16th and 17th century in Europe. It was ratified in 1648 at the Treaty of Westphalia which essentially reified the state as an individual. It ended the thrust of European struggles to reunify Europe’s peoples under a single hegemonic state and religious system.

Nearly 400 years on we find the nation state struggling in the face of globalization. It is also struggling with ecological crisis. Both globalization and the environment have little regard for borders. Yet we see new Humanist strategies creating new pathways into the future by granting to natural systems such as the Ganges River, human rights. I love the idea that the Earth and its systems can be acknowledged as deserving of human rights. But there is a problem in that Earth systems are being addressed within a legal and cultural system that is deeply wounded. We can see indigenous people having sovereignty acknowledge yet the dominant logic of capitalism still marginalizes such peoples. The Chorus is however there and pushing for an expanded consciousness. And Neohumanism offers a solid and historically intelligible extension in the struggle to achieve a more just world.

We need to move beyond the Humanist agenda. Despite the immense vulnerability of billions of human beings, we cannot separate the fate of people from the fate of the natural world we inhabit. This is the Humanist dilemma. By privileging humanity as planetary stakeholder number one, we forever marginalize all other planetary stakeholders. Neohumanism ultimately offers a Cosmic agenda, one that potentially redresses the power and relational imbalances to which Humanism is blind. So to summarize some of this thinking around Neohumanism as it has evolved through a dialectic process with my teaching I offer the following thoughts.

Cosmic Agenda

Neohumanism has a Cosmic agenda. It is a philosophy that challenges the borders and distinctions that have characterized modernity by offering integrated diversity as a basis for identity and critical spirituality as the basis for analysis of assumptions and practices sustaining the status quo. This means that categories such as internationalization and interculturality are understood as historical, becoming transitional lenses through which to approach transformative futures. These categories are processes that gesture towards futures beyond the nation state and identity. In the academic sphere, inter and trans-disciplinarity similarly points to a world in which the disciplinary boundaries that often inhibit deeper scholarship and pragmatic engagements with our world, break down.

Once we understand that Neohumanism has a cosmic agenda then we can stop worrying about the clock. The clock brings a sense of urgency to the present. Can you hear it ticking like a time bomb? We have a sense that the Anthropocene is an end of times. Urgency can promote action, but it also reduces our ability to operate across the many pasts, presents and futures that intersect in our present. Neohumanism has a Cosmic clock, one that offers us an evolutionary perspective (M. Bussey, 2017b). Our human agency shifts gear with such a clock. It offers us open futures that are not corralled into a doomsday present such as that offered by a category like the ‘Anthropocene’. Remember, categories are historical. The Anthropocene is a category developed by well-meaning scientists who are deeply concerned about the impact of human activity on the planet (Crutzen, 2016; Steffen, Crutzen, & McNeill, 2007). But, is it an enabling concept? I feel it has utility value, but I am not inclined to rely too heavily on it because it offers us a diminished future. It is not psychologically nurturing. Put another way, we could say it is diagnostic but not curative.

Furthermore, Neohumanism is a benevolent philosophy. Whilst the term ‘Anthropocene’ is a noun (or a pronoun), Neohumanism has an actional, verbal orientation. It speaks directly to an approach to life and its many futures that is relational. It validates as essential ingredients in optimal futures both spirituality and love. Sarkar describes this actional quality as ‘Mission’ (1982, p. 99ff). Meditation, more broadly spiritual practice, is life and world affirming. It is practiced to enable us to better serve this world. It is not an escape from the world. The philosophical lens of Neohumanism in turn places humanity in a Cosmic story that makes sense of struggle as a tool for the evolution of consciousness. Yearning is the driver in this process. Benevolence, is the compass and critique the tool for loosening the ties to elements of the past-present in culture that warp our ability to discriminate between self-interest and subservience to toxic assumptions about reality, essentially diminishing our personal and collective agency.

Conclusion

Today we do not find either spirituality or love on the agendas of scientists or politicians. We live in a cynical age. Such an age promotes consumption in an attempt to fill the void within ourselves and our cultures. Like Humanism, Neohumanism is optimistic, seeing the best in humanity without glossing our shortcomings. Like humanism it puts its hopes in an educational project designed to liberate human consciousness, from the bonds of the petty and the mundane (M. Bussey, 1998; Sarkar, 1998). Humanism, that great intellectual project of the late European Middle Ages and Renaissance was optimistic but blind to its own Eurocentrism and complicity in colonialism and imperialism. Neohumanism is an engagement with the Humanist spirit but hybridised with non-Western Tantric models of what it is to be ‘human’.

To be a ‘global citizen’ today reaches new heights and depths when understood through a Neohumanist lens. Just as Humanism promoted the vision of a human family, so now we need an expanded vision to help us understand and act with responsibility towards out Cosmic family. I understand Neohumanism as a Cosmic Story with evolutionary potential (2009). It places humanity in relation to all that is beyond us. It allows us to experience mystery and awe when facing the Cosmos and our place within it. As a living map Neohumanism responds to the possibilities and terror of our time of transition. This is not an easy or simple thing. The complexities and uncertainties that shape our current context are beyond us. We need to work on ourselves as consciously becoming beings with big hearts and open minds. We need to think collectively and work to address the injustices and violence of the present. We need to work as servants to the future, understanding that this moment is one of open-ended time. Perhaps the clock is ticking too loudly? For me each breath is a miracle and when I am teaching, to share in this amazing unfolding is certainly enough.