Introduction

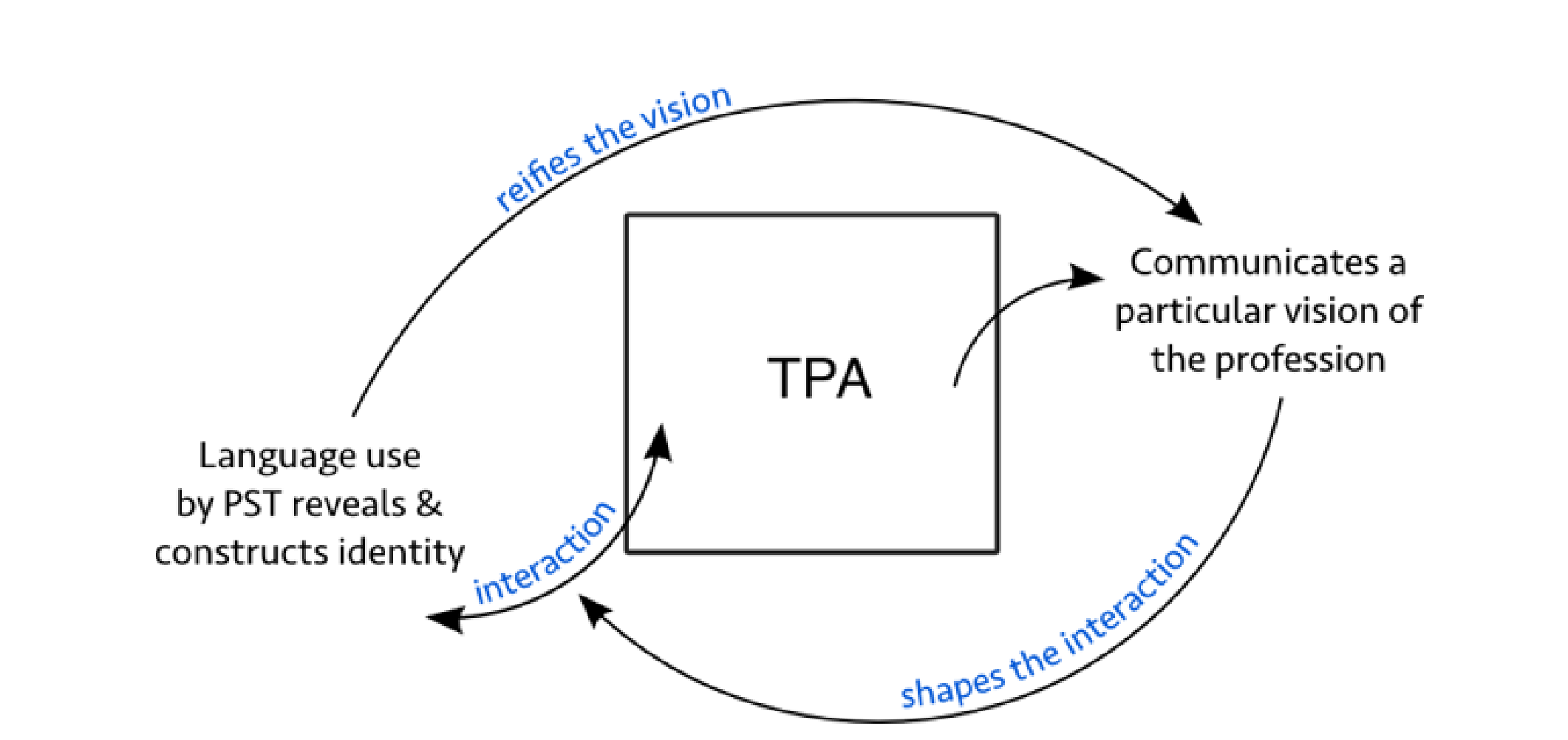

Teacher performance assessments (TPAs) sit at the intersection of teacher education reform, the professionalization of teaching, and the high stakes assessment climate. TPAs offer a way to evaluate pre-service teacher (PST) learning and ability as they engage in authentic teaching tasks – (e.g. planning, instructing, assessing, and reflecting). When completing a TPA, PSTs typically write a detailed account of this process, and it is assessed alongside a video or observation of the instruction described in the assessment. While performance assessments can take multiple forms and be used for multiple purposes (and in multiple stages) in a teacher preparation program, they have recently become a popular form of high-stakes assessment in teacher education. High stakes TPAs are used as gatekeepers – ostensibly allowing only capable candidates into the profession; consequently, serving as a professionalizing tool. A completed TPA reveals how a PST uses language to position themselves within the realm of what it means to be a teacher. In this paper, I use discourse analysis to investigate this complex positioning process paying particular attention how the assessment communicates a particular vision of the profession to novices.

Performance Assessments for Teaching

Teacher licensing has long required assessments of teacher capacity. While these requirements vary based on state credentialing policies, traditionally, teacher capacity was evaluated via paper-and-pencil tests that assessed content knowledge of subject areas in which prospective teachers hope to become licensed. These assessments prioritized mastery of content knowledge over pedagogy or pedagogical content knowledge. While there are a few pencil and paper tests that do seek to address pedagogical skills through scenarios, these are inauthentic (i.e. not based in actual practice), and limited in their capacity to mimic the interconnected and multifaceted nature of real-time teacher decision-making (Darling-Hammond, Wise, & Klein, 1995).

TPAs grew in popularity and use in teacher education and professional development during the 1990s and 2000s for two reasons. The first is that they were developed as authentic measures of teacher learning and quality that foreground the complex nature of the work of teaching. TPAs are argued to be more robust measures of teacher development because they assess an authentic, in-context process of teaching and learning (Wei & Pecheone, 2010). The second was that as accountability demands for teacher preparation were mandated (as a result of politicians and educational reformers questioning the effectiveness of traditional teacher preparation), performance assessments offered a measure that teacher education programs could use as justification of their utility.

Pact

In 1998, the state of California enacted a law requiring that all new teachers, regardless of their pathway into the profession (alternative pathway or traditional teacher education) pass a performance assessment linked to professional standards. The Performance Assessment for California Teachers (PACT) was developed by a consortium of university programs to serve as an alternative to the TPAs that were commissioned by the CCTE (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing) and developed by Educational Testing Services (ETS). PACT was designed to assess PST performance during a specific teaching event of between three and five lessons. The assessment sought to integrate and assess four different parts of what is typically thought of as a lesson cycle – planning, instruction, assessment, and reflection. Teacher candidates were expected to design their teaching event around content area and academic language goals for their students. PACT assessments were subjectspecific and are scored on a rubric that addresses all four teaching tasks. Scorers had expertise in the content area or grade-level described and have received training on how to score PACT tasks. PACT was used broadly in California until the development of edTPA, which is explored below.

National Landscape of Teacher Performance Assessments

A decade after the development of PACT, SCALE (the Stanford, Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity) engaged in a national campaign with AACTE (American Association for Colleges of Teacher Education) and Pearson, Inc. to develop a national performance assessment for teaching. The outcome was edTPA, a national teacher performance assessment aligned to the Common Core State Standards. edTPA is being used across 41 states, in over 800 teacher education programs. 17 states have adopted statelevel licensing policies requiring performance assessments for licensing and have adopted edTPA as at least one option for meeting this requirement (edTPA, 2019), and supporters hope that edTPA will become part of a national licensure process (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

TPAs are used as tool for education reform. As a component of teacher licensing, performance assessments are part of a professionalizing agenda in teacher education (Darling-Hammond & Hyler, 2013; Sato, 2014). TPAs act as a gatekeeper to the profession, and demand that new teachers demonstrate a mastery of the complex nature of teaching. Rigorous gateway assessments are a facet of established professions, like medicine, law, and accounting (Darling-Hammond et al., 1995). Efforts at professionalization often involve finding ways to emulate professions, like these, that have higher societal status. The fundamental premise of high-stakes professional entry assessments is that if professional ability can be accurately measured, the result will be a more capable and qualified cadre of teachers, as inept prospects will be denied access. This elimination process would, therefore, contribute to developing a profession deserving of higher societal status, because it is solely comprised of members who have proven themselves capable. The most recent data on edTPA indicates that 75% of PSTs pass the exam (edTPA, 2018), although pass rates are much higher at some institutions (Ledwell & Oyler, 2016).

PACT and edTPA are part of a long-term professionalization agenda in teacher education. TPAs are an attempt to locate the gatekeeping mechanism for entry into teaching in the hands of the profession, instead of simply in the hands of the state (which manages methods of and pathways to certification). Required performance assessments also serve as an accountability measure for teacher education programs. The proliferation of edTPA may be currently apropos as national leaders are calling for greater accountability of teacher preparation (Greenberg, McKee, & Walsh 2014; White House Press Secretary, 2014). If an accepted version does not emanate from the profession, one will likely be forced upon teacher preparation from outside sources. External versions would likely focus on quantitative measures (e.g. valueadded measures) that reduce teaching and learning to what can easily be measured on standardized assessments, removing a great deal of the complexity from the assessment of teaching and further limiting the kinds of pedagogical approaches that new teachers might pursue.

Performance assessments are not without critique, most significantly from within the field of teacher education. There is concern about mandated for-profit, corporate involvement (via Pearson) in teacher preparation (Madeloni, 2014; Tuck & Gorlewski, 2016). High-stakes professional entry assessments also have a tendency (often by design) to shape the content of the professional preparation programs. Since the nationwide implementation of edTPA, teacher educators have raised concerns about how the high stakes assessment constrains the program’s curriculum, reducing the attention that can be paid to aspects of teaching and learning that aren’t assessed by the TPA (Dover & Schultz, 2016). This in turn may limit the relational, emotional, and critical aspects of teacher preparation (Madeloni & Gorlewski, 2013). This practice also downplays the importance of relationships within teacher preparation by outsourcing evaluation of new and prospective teachers to external scorers and reducing PSTs and their learning to a numerical score (NAME, 2014). There is also concern that high stakes external assessments are in tension with efforts to diversify the workforce, because they create increased barriers for historically marginalized populations, such as PSTs of color (Petchauer, Bowe, & Wilson, 2018).

Discourse Analysis of Performance Assessments

TPAs have emerged as an important component of teacher preparation and licensing reform at the national level. They serve as a mechanism of teacher education program accountability, a tool for measuring teacher capacity, and as a document that communicates professional expectations. All of these functions are carried out through the use of language. PSTs reveal their understandings of their role through the detailed description of the practice. The performance assessment conveys the essential areas of practice through its structure, consequently communicating to new teachers what the most important aspects of teaching are.

Analyzing the language used and purposes for language inside of a teacher performance assessment is a valuable analytical tool for investigating new teacher development and how a common conception of professional is constructed and communicated through language. One level of this analysis focuses on how PSTs construct their professional selves for evaluation. Discourse analysis provides a window into teacher development as it allows the researcher to probe deeply into teacher knowledge, identity, and thinking processes. New teacher development is an ongoing process that begins long before a prospective teacher enters a pre-service preparation program and is affected by a multitude of factors and relationships both inside and outside of formal teacher education (Olsen, 2008). A performance assessment serves as an avenue for investigating this development process because a close analysis of language use can reveal a PST’s current position in this developmental process as he/she is exiting pre-service education and preparing to enter his/her own classroom as the teacher of record. For example, a close analysis of a multiplesubject literacy performance assessment can provide evidence of how a new teacher defines literacy, constructs a literacy teaching practice, and what he/she believes the appropriate roles for student and teacher are. The process of constructing a professional self for evaluation purposes is a negotiation between the demands of the performance assessment and the identity of the PST. PSTs position themselves within the particular language used in the assessment and simultaneously within the larger discourses of education and teaching. However not all kinds of teachers and teaching methods are positioned equally in a performance assessment response. This connects with the second level of analysis, which examines how the language in performance assessment questions reveals a preference for a particular form of teaching. Discourse analyses of performance assessments not only illuminate aspects individual teacher development, but also open up pathways for investigation of the particular demands of the assessment tool. Analyzing the particular demands of the assessment leads to a deeper understanding of how and why novice teachers construct particular responses. It also provides insight into how a high-stakes entry assessment constructs a particular form of the teaching profession.

This analysis combines sociolinguistic approaches in order to better understand the individual development and sense-making of novice teachers. Critical discourse analysis is also utilized to uncover the ideological assumptions at play in the assessment structure, and describe how those structures contribute to a certain construction of the teaching profession.

This paper demonstrates how discourse analysis tools can be applied to a performance assessment, using a PACT assessment completed by a PST (who will be referred to as Jordan) as part of a graduate level credential program at a university in California. The written portion of the assessment (PACT also contains a video component that was not analyzed) was randomly selected by a program employee and contained no identifying information. Jordan was a multiple-subject credential candidate, and therefore the PACT focuses on an elementary literacy lesson sequence. The teacher education program Jordan attended has a social justice focus and emphasizes sociocultural approaches to teaching and learning.

Sociolinguistics

Sociolinguistics represents a broad group of functionalist linguistic approaches that examine language in use (Lakoff, 2000). This paper uses one sociolinguistics approach, pragmatics, to better understand the interaction between the PST and the performance assessment and investigate new teacher development through her communicative intent in interaction with the assessment. The following section presents how a particular sociolinguistic analytic illuminates Jordan’s emerging teacher identity. Identity is used here as an amalgamation of beliefs, understandings, and current conceptions. Understanding teacher learning as identity development emphasizes that an identity is constantly in process, however most attempts to analyze identity render static something that is ongoing. Identity is also a combination of narrativized aspects – or stories teachers create about themselves, as well as positioned aspects – labels and categories applied to teachers from the outside (Holland, Lachiotte, Skinner, & Cain, 1998). These two categories are precisely what this discourse analysis attends to – a combination of the ways that teachers present themselves as well the positions made available in the structure of TPA.

Pragmatics Analysis

Pragmatics is a branch of sociolinguistics focused on speaker meaning. Pragmatics focuses on the individual meaning that each speaker (in this case, author) intends to communicate with listeners (readers). A central concept in Gricean Pragmatics is the notion of implicature, which is “an inference about speaker intention that arises from a recipient’s use of both semantic meanings and logical principles” (Schiffrin, 1994, p. 193). Thus, pragmatics directs attention on the inferential relationships that are created between speakers. These inferences are based on general assumptions that the speaker and hearer bring to the conversation. The verbs that a PST uses to describe her work and that of her students provide insight into how the teacher understands her role and the role of students during a lesson. Using pragmatics, descriptive snippets of student teacher interactions during a lesson can be analyzed linguistically in order to develop a deeper understanding of PST identity development. Whether or not the description of the instructional event is an accurate depiction of what occurred is less important than the way the PST chooses to present it. Through her description, the PST is providing a particular kleipresentation that may be more valuable for understanding the PST’s current conception of her role than an observation (or video recording), because it provides a sort of commentary - both in the explanations for why she engaged in certain activities but also through the particular words she used to describe the interactions.

One way to linguistically analyze a TPA for speaker meaning is to examine the verbs used by the PST in the assessment. Task 3 of PACT is an instruction commentary where PSTs describe what happened during the focus lesson that was video-recorded and submitted along with the written portion of the assessment. A closer look at the verbs that Jordan used to describe her actions and those of her students can help illuminate how she understands her role as a teacher. Simply counting the action verbs [1] used in the section to describe what the teacher does and what the students do is revelatory. Jordan uses 35% more teacher action verbs than student action verbs. 98 verbs were used in describing teacher actions versus 65 verbs used to describe student actions (including both student actions that actually occurred and those that were just expected or desired by the teacher). The focus of her commentary emphasizes the teacher’s role in the instructional activity rather than the student one. This is partly due to the way PACT frames the questions throughout the task – they ask her to focus on her own actions. For example, prompt four asks:

In the instruction seen in the clip(s), how did you further the students’ knowledge and skills and engage them intellectually in comprehending and/or composing text?

Only one of the five prompts in this section requires the PST to describe student actions. This focus on teacher actions may be logical; this is, after all, a teacher assessment (not a student one). However, this sort of framing can reinforce a teacher-centered notion of instruction. The kinds of frames presented shape the way that Jordan understands her role and the instructional activity, which meant the emphasis of her commentary (and therefore the available depiction of her lesson) was not on how students made sense of the characters in the text.

Some of the verbs were repeated; for example, Jordan used ‘asked’ to describe her actions five different times. By eliminating repetitions, the list was reduced to 51 unique teacher action verbs and 35 unique student action verbs. Additionally, some of the verbs were synonyms that described very similar actions. For example, Jordan also used ‘posed a question’ six times to illustrate the same (or a very similar action) to ‘ask’. Accounting for these close similarities, reduced the count to 42 unique teacher action verbs and 30 unique student action verbs. A comparison of the type of verbs used to describe actions the teacher took versus actions the students took demonstrates the kinds of interactions that this teacher believes should take place in a classroom. For example, Jordan uses a version of the action ‘ask’ 16 times during the instruction commentary to describe a teacher action. (This includes permutations of ‘pose’ and ‘call on’). Sixteen percent of the teacher actions fall into this group, more than any other category of teacher actions. Conversely, only 7% of the teacher’s actions fall into the listening category (a broad group of terms including: analyzing, checking, seeing, informally assessing, and monitoring). Finally, none of the student verbs involved asking, while 25% of student actions consisted only of the verbs respond (n=10) and answer (n=5). This begins to paint an image of a teacher who understands a primary part of her role as one who poses questions to students, and their role is to respond. But students do not ask questions of her (or of each other), or if they do, this isn’t the primary work of learning literacy. A traditional instructional pattern begins to emerge from this verb analysis, where the teacher, as the bearer of knowledge, directs the lesson, and students provide answers to questions when prompted.

There are dangers in removing too much of this discourse analysis from the actual content of the text. Therefore, analyzing brief scenes of the lesson in context can paint a more cohesive picture of the kinds of roles made available for the teacher and students by the design of this lesson. In this scene, Jordan describes how she “further[ed] students’ knowledge of the text” during a read aloud activity. In it, she emphasizes the academic language focus of her lesson. The verbs used in this scene demonstrate several kinds of activities that she engaged in during this lesson segment. They are bolded in the version below.

Table 1 Verbs in Context

| 1. During the first part of the lesson, I provided definitions and examples for any vocabulary words or concepts that were new or unfamiliar. |

|---|

| 2. For example, when the word “ostracized” comes up in the text, I allowed students to talk to their partners and see if they could come up with the definition (which we had discussed in a previous lesson). |

| 3. When I called on an individual that had raised his hand to respond, he stated. “It means that they go to the very end of town.” I clarify by saying, “yes, they were kicked out of the town and they had to live on the very edge of town away from their community.” |

| 4. Similarly, I provided an example of a “possession,” when that key word came up in the story. |

| 5. When a student pointed out that a woman from the story “is saving a baby sheep” in the illustration, I took the opportunity to use that as an example of a possession by stating that it is something that is important to her that she owns, her possession. |

In turn 1, 4, and 5, Jordan understands her role in supporting student learning to be providing information to students. One of the key pieces of information seems to be examples, so that they can grasp the meanings of particular vocabulary words. In turn 2, Jordan uses the verb ‘allow’, which carries in it a great deal of teacher authority. This student-to-student talk would not have been permitted without the express consent of the teacher. This almost seems to indicate that the student-to-student talk was extraneous or at least of questionable worth, as though the primary work of learning happens when the teacher provides information, not when students talk with their partners. Implicit in turn 2 is a question that the teacher likely raised concerning the definition of the word ostracized. She follows up her question by calling on a student to define the vocabulary word ostracize. The student’s response is a factual account of what occurred in the story, but lacks the nuance added by this particular word. Jordan ‘clarifies’ the meaning. The use of clarifying here is of note. She could have stated that she ‘expanded’ the student’s response, or that she ‘corrected’ it. Clarified is somewhere in between. With the use of the word clarify, Jordan demonstrates that she recognized the value of the student’s initial response, but that the definition the student presented did not match the understanding of the word that she hoped her students would gain from the lesson. In turn 5, Jordan depicts a moment where she takes advantage of what is commonly called a ‘teachable moment’, an unplanned instance where a teacher can offer insight or instruction. Jordan uses the observation of a student to reinforce her learning goals and provide another example of one of the focal vocabulary words.

The teacher role depicted here is one that provides information, poses questions, calls on students, and clarifies student responses for accuracy. Students respond to questions raised by the teacher, talk to each other when directed, raise their hand to be called on, and occasionally make other observations about the text. In this exchange, we see the traditional IRE pattern of classroom discourse (Cazden, 1989). The teacher initiates, a student responds, and the teacher evaluates. Wells (1993) expanded the IRE pattern to include an IRE/F, where the teacher often provides feedback instead of or in addition to an evaluation. Jordan provides feedback when she clarifies the student’s definition of ostracized. The evaluation is implicit, because the clarification indicated that the student was not (entirely) correct in his/her response. The actions depicted by the teacher in her description of this scene demonstrate a traditional role of student and teacher. This PST is constructing an understanding of her role as someone who presents, asks, and evaluates student responses. She furthers student learning by serving as the impetus to move along the lesson and the director of linguistic interactions. Jordan does the majority of the talking and students listen attentively (at least ideally) in order to develop understanding of word meaning. Her conception of the role of the teacher is an integral part of her identity development process. She is not only constructing an image of a teacher, but also a professional sense of self, which she will in enact in her future classroom. It ceases to be a generic or general role, and becomes a very personally one as Jordan integrates it into her own teacher identity. In the next section on critical discourse analysis, this discussion of teacher and student roles will be expanded to discuss how and why these roles operate as dominant subject positions that are both commonplace and constraining.

Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is an approach to understanding and analyzing language and its connection to larger power structures in society. It has roots in Neo-Marxism and poststructuralism and connections to critical theories in a range of disciplines, however, its uniqueness lies in the connection of discourse analytic techniques to theories of social reality (van Dijk, 2001). CDA understands texts as both representative of ideologies and - through language in use - a process that constructs social reality often reproducing those same ideologies.

The goal of critical discourse analysis is to unmask the ideologies that are often taken for granted in everyday language use. Texts are created out of available “orders of discourse” (Fairclough, 1999, p. 184). Discourse analysis “draws attention to the dependence of texts upon society and history in the form of the resources made available within the order of discourse” (Fairclough, p. 184). Ideology isn’t necessarily translated whole into new settings, but rather interacts with other influences to apply a normalizing force to new teachers. This normalization communicates messages regarding what ‘counts’ as quality teaching in the professional field: what quality teachers should look like and do. The traditional model of teacher-directed instruction likely matches a PST’s own schooling experiences and fits well within the current climate of basic skills teaching, standards and standardized assessment, and measuring the quantifiable value that teachers add to students through their actions in classrooms. This combination of influences and relationships interact to shape the way that new teachers construct their professional selves. TPAs operate as one thread in this larger web of discourse relationships that (re)constitutes the professional field of teaching through practice.

The following section uses CDA to investigate of the text structure in the assessment in order investigates the demands PACT places on PSTs by unpacking the content of a PACT prompt. Both of these analyses demonstrate how micro analytic techniques can be linked to larger explanations of how ideology, discourse, and power work to maintain the status quo in education.

Analyzing PACT Demands

The demands of a performance assessment are located in the prompts, which communicate more than just a traditional view of teacher and student subject positions. These demands have important effects at multiple levels. First, they demand certain actions of teachers in training. These new teachers then carry out these demands (or some facsimile thereof) in real practice. This attempt to meet these demands, and then provide a thorough account and reflection of their actions is part of their self-construction process as new teachers. While it is likely that PSTs are (to varying degrees) aware of the intentional demands of this assessment and how this process may or may not be shaping their process of self-formation, PACT is the arbiter of a state sanctioned and required professional standard. In this role as arbiter - it constructs a particular vision of the teaching profession. And the demands of the assessment sit at the intersection of shaping individual new teachers and constructing a profession (and doing so by shaping new teachers to meet this professional model). Discourse analysis of these demands uncovers how this cycle may occur in practice.

PSTs are required to provide a contextual background of the school, their placement classroom (where they are placed as student teachers), and the students in the class. They are asked to describe students’ academic, language, and social development as well as local family and community contexts. They are later required to explain how they will directly build upon their knowledge of students to develop their academic skills as well as design their lesson.

Given the description of students that you provided in Task 1.1: Context for Learning, how do your choices of instructional strategies, materials, technology, and the sequence of learning tasks reflect your students’ backgrounds, interests, and needs? Be specific about how your knowledge of your students informed the lesson plans, such as the choice of text or materials used in lessons, how groups were formed or structured, using student learning or experiences (in or out of school) as a resource, or structuring new or deeper learning to take advantage of specific student strengths (emphasis in original).

This is a broad demand, which allows PSTs to interpret it in a variety of ways. It provides the opportunity for new teachers to take a culturally responsive approach to design instruction that reflects and engages students’ backgrounds and interests (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Villegas & Lucas, 2002). It even suggests that students’ learning experiences outside of school can be used as a resource for school-based practices (Moll, Amanti, Neff & Gonzalez, 1992). However, these are inferences made by someone (me) who knows these approaches and is committed to them. PACT may leave the door open for PSTs to engage culturally-responsive pedagogies, but it is never explicitly stated, and certainly not required. This sends a message that those tools are extraneous, not central to the work of teaching; they are extra not obligatory or essential. New teachers with minimal training may be unlikely to engage in this kind of demanding and time-consuming work (even if they are committed to the ideals) when they already have many, overwhelming demands on their hands. Since culturally responsive approaches are subtly deemed as supplementary, these pedagogies may be less likely to become part of their new professional identity.

Attention to what is in the demands also requires analysis of what isn’t present in PACT (Luke, 2002). PACT does not require PSTs to gather knowledge of students outside of school. They aren’t expected to develop an understanding of the kinds of literacy practices that children or their families engage in at home or in their communities. This would be a taxing request to put on PSTs, but if teachers conceive of literacy as a social practice, understanding these practices and using them in the classroom as valuable instructional resources is not just an added-benefit for making teaching relevant, but actually imperative for developing and investigating literacy. This continues to position culturally relevant approaches to teaching that centralize community funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992) as complementary and not central to literacy instruction.

In the response to the prompt above, Jordan speaks in vague and general terms about her knowledge of the students in the class. She states that they “have a large range of literacy abilities” and “learn best through experience”. No particular interests or strengths are discussed and there is no mention of any resources outside of school that she draws from in her lesson design. Jordan’s perspective on what resources children have to bring to the literacy learning process (cognitive or other) is corroborated by her approach to the reading lesson. Students are prompted to make quite specific meaning of a read aloud story; they are not asked to bring their own knowledge to bear on the story in order to make connections or interpret the meaning. “Students will work in pairs and generate ideas of connections made between characters and events that they are assigned from the story” (emphasis added). Jordan determined what was important from the story and what interpretive activities were needed in order to understand what was important. Students were not asked to bring in their own knowledge or experience to the text to make sense of it.

There are several possible explanations that contribute to Jordan’s construction of this lesson. She could be engaging in a version of close reading. Close reading is a strategy being supported by new Common Core ELA developers (Pearson, 2013; Coleman & Pimental, 2011). Some approaches to close reading emphasize constructing understanding solely from the information in the text, and minimally engaging in analysis, interpretation, comparison, or connection (or at least not until thorough literal comprehension of the text has been demonstrated) (Pearson, In Press). This may also be a product of Jordan planning a lesson that is closely wedded to the standards. The lesson is designed around Common Core ELA standard 3 for Kindergarten:

With prompting and support, describe the connection between two individuals, events, ideas, or pieces of information in a text.

The essential question that Jordan developed for the lesson is simply the standard reworded: “How are the characters connected to each other and events in the story?” Jordan understands this to be a foundational skill that is “representative of a skill that will be present throughout their studies with literature in school.” It is likely that there are multiple factors that contribute to this particular instructional decision, but what is of interest here is how PACT makes multicultural and culturally responsive approaches to teaching supplementary. This may designate those approaches as a dispreferred move for new teachers and puts them outside the demands of a professional teacher. The dispreferred move is a sociolinguistics term regarding interactional speech patterns. In a conversational exchange not all responses are equally positioned. For example, if someone asks “How are you?”, the preferred response is some version of “Fine.” If the interlocutor deviates from the preferred response, an account or justification must be made for that deviation. Rarely does one respond to the question “How are you?” with a simple “Not good.” Normally, “not good” would be followed by a justification, such as “Not good, my dog just died.” Where the preferred response does not require a mitigation or justification, the social practices that guide interaction indicate that a dispreferred response does. This is a sort of unwritten rule of (at least Western) conversation that most Westerners abide by, and when someone deviates from the norm, it is a noticeable aberration. In much the same way, if PSTs abide the traditional, teacher-centered, a-cultural practices implicit in PACT, they are engaging in the preferred move. It doesn’t mean a different approach isn’t feasible; simply that it isn’t encouraged (and that it isn’t the norm). It may also require a kind of explanation and justification that isn’t otherwise necessary.

Conclusion: The (Re)Construction of a Profession

The structure of a TPA doesn’t necessarily foreclose other pedagogical approaches (i.e. ones that are more critical or constructivist); it is simply inclined towards more traditional ones. PSTs could successfully complete the PACT using those approaches (Sato, 2014). But because they are not central to completion of the TPA, those other approaches are extraneous, extra, or additional, not central to the act of teaching. These implicit messages not only designate appropriate pedagogical tools and strategies, but also define what the foremost goal of the act of teaching should be. Teaching may always have multiple goals - helping students learn to read, inspiring future biologists, teaching them how to interact with others, or creating good citizens. The primary purpose communicated through the TPA is to teach students content. The substance of the content is predetermined in standards. The approaches to teaching content may vary, but the goal is content learning. Conversely, other approaches to teaching might foreground raising a critical consciousness (Freire, 1970), teaching towards democracy (Sleeter, 2013), learning as engaging in inquiry (Klein et al., 2013), or creating a more equitable society through education. Critical approaches to teaching and learning don’t eschew content learning and skill development, but do so through the means of consciousness raising (Freire, 1970) or at least simultaneously. Perhaps the most successful efforts have been those that make the critical part of the content (The New London Group, 1996). But this is not what is centralized in PACT. Again, teachers may be able to use critical or inquiry centered approaches, but they would likely have to justify them, connect them to content standards, and put in additional effort to clearly communicate things that may be accepted and implied in more teacher-centric lessons.

High stakes assessments (whether they are performance based or take traditional forms) reinforce standardized notions of knowledge and instructional practice, which some argue is always an oppressive act, as the favored forms of knowing and being (and in this case, teaching) tend to recreate established power relations in society by privileging the dominant white, middle-class, male, heterosexual norms (Madeloni & Nygreen, 2014). PSTs may be discouraged from attempting pedagogies that may not score well on the performance assessment rubric and/or from experimenting with collaborative or social-justice oriented lessons that may be more challenging than traditional, didactic instruction (Madeloni & Gorlewski, 2013). TPAs can control and quantify teacher education by codifying what teaching should look like, which tends to emphasize traditional didactic approaches over student-centered, progressive, multicultural, or critical approaches to teaching (Reagan, Schram, McCurdy, Chang, & Evans, 2016).

Given that critical approaches to teaching and learning literacy have never been mainstream - it is not surprising that they didn’t make into PACT. TPAs might incur a great deal of outside criticism (as “soft pedagogy”) and be even less likely to be accepted (and approved as a legitimate version of new teacher and teacher prep accountability) if it included direct or specific connections to multicultural, critical, or sociocultural approaches to teaching and learning. When combined with the sociolinguistic analysis of Jordan’s instruction, a pattern of traditional, didactic instruction begins to emerge. Through the process of utilizing the traditional discourse types, Jordan reifies these social patterns of interaction. While Jordan is developing her own professional disposition, constructing a role that feels comfortable for her. She is becoming a particular kind of teacher. This does not assume that she will continue to teach in teacher-centered ways forever, but the traditional subject positions of teacher and student are easy to inhabit, because they are comfortable, recognizable. They are a part of normalizing forces of the institution of school (Foucault, 1977). In much the same way that Jordan is recreating this structure with her kindergarten students, the assessment serves a similar purpose with her. By demonstrating what is the standard, acceptable, approved, and professionally sanctioned role of a teacher in a classroom, PACT teaches Jordan to align with its implicit teacher-centric professional vision. While TPAs may have shielded teacher education from more reductive and draconian forms of PST assessment, the resulting performance assessment may contribute to another generation of didactic, teacher-centered instructors.