Four years ago, 2-year-old Joaquín’s mother carried him for the long walk to the bus stop, on the bus, and from the bus to Teletón. Teletón is a rehabilitation center in Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. At the center, Joaquín and his mother waited until their appointment time, when a physical therapist greeted them and took Joaquín to the therapy room. There, she manipulated his joints, working on contraction and extension, and she again held him in standing to see if he could take his first step with her assistance. After 40 minutes, if he lasted that long before crying, the therapist returned him to his mother. The therapist sometimes had a suggestion for her to try at home. Joaquín’s mother checked with the receptionist about the appointment for the following week and she began the long trek home.

Today, Joaquín and his mother still come to Teletón. He now walks with arm crutches, with a slow and awkward gait. At therapy time, both he and his mother go to the therapy room with the physical therapist, who makes sure he has access to toys and books. Most of the session involves Joaquín’s mother and the therapist talking. They discuss the mother’s success with the interventions she said, at the previous session, she wanted to try through the week. They discuss how different times of the day are going, with respect to Joaquin’s engagement, independence, and social relationships. They discuss progress the mother has been making on finding a car she can afford. They look at the ecomap the two of them had made some months earlier, to see if someone in the family’s informal support network might help. When talking about outings, Joaquín’s mother says she is worried Joaquín will fall going up or down a curb; she still has to lift him almost. The therapist asks if she’d be interested in figuring out a better way to help him. When the mother says yes, they take Joaquín for a walk. They go to a curb on to the parking lot of Teletón. The therapist observes how mother and son negotiate the curb and asks if she can try. She tells the mother what she is going to do, to support him on his hips, instead of under his arms. She demonstrates, telling Joaquín to step up and then down, while supporting him at his hips. She asks the mother if she would like to try. She does, and the therapist coaches her through the process. Before they leave, the therapist writes short notes about what they did on the visit, asks the mother what she will do between now and the next visit, and asks the mother what she would like the next visit to focus on.

These two visits are different, not because Joaquín is now six years old instead of two. They are different because Teletón is implementing a completely different way of doing their work. This article describes and briefly analyzes the implementation of this innovative model.

An Organization With High Ideals

The Teletón context is important for understanding the strengths and challenges involved in making this change. We describe here what they thought needed to change and how they arrived at those conclusions.

Structure

Teletón is organized in four rehabilitation centers distributed in four locations in Paraguay: Asunción, Coronel Oviedo, Paraguarí, and Alto Paraná. These locations make it more possible for families from around the country, including rural areas to have access to services. In these centers, beyond rehabilitation, Teletón attends to family needs from a comprehensive and holistic perspective. As we will see, the philosophy of the current leaders was family centered even before implementation of the model. The difference now is that they have a path to follow.

The four sites differ in physical size, in the number of professionals, and in the context of each center’s region. The contexts are mostly determined by the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of families, their ability to get to the center, and language. Paraguay’s regions differ by language: in some places, mostly Guaraní, the indigenous language, is spoken. In others, mostly Spanish is spoken. In yet others, Portuguese is the most prevalent language. The one way in which the sites do not differ is the children’s diagnoses.

Purpose

Teletón (meaning telethon) serves children with physical disabilities. It is part of a larger network of Teletón rehabilitation centers throughout Latin America. The term rehabilitation has always been linked to Teletón. Each center is called a Teletón Integral Rehabilitation Center (Centro de Rehabilitación Integral Teletón--CRIT). The organization has always had a clinical purpose but also a goal of inclusion: If we provide children with effective therapy, they will be better able to be included in society. Today, the goal is more advanced than having inclusion as an outcome only. The manner of doing business itself is now more inclusive. The staff point to the fact that they have dropped clinical language that medicalizes consumers. They used to refer to them as patients or individual users. Now, they refer to them as children and families. Teletón’s leaders say their purpose now is to improve children’s quality of life (QoL) and family quality of life (FQoL).

In Paraguay, a national effort is under way to improve the QoL and social inclusion of people with disabilities, and Teletón is part of that effort. Because Teletón is just one agency and does not have all the resources that might be needed to achieve this goal, it generates alliances and works in networks consisting of agencies from the public and the private sectors. In addition, Teletón is active in communicating support for principles of inclusion and QoL, creating social awareness so the community and society generate the optimum conditions for people with disabilities to participate in society. Beyond what happens in the CRIT, a whole network of volunteers and collaborators contribute to the mission and work of Teletón. Collaborators include schools, universities, students, agencies, mayors’ offices, health centers, and municipalities. Support and volunteering is frequent, helping put into effect the organization’s commitment to human rights.

Teletón, true to its name, raises 70% of its funds through an annual 27-hour, uninterrupted program telling stories of children and families helped by the organization. Most donations are from individuals, rather than companies. They also host a large solidarity meal, which raises considerable funds, and conduct a few other fundraisers. No money comes from the government. A national law has reduced the amount of funding allocated to nongovernmental organizations. In any case, state-funded services for people in need are grossly inadequate. A National Disability Secretariat exists, but its coverage is sparse, with most people with disabilities not receiving services. In 2012, the national census revealed that 11.4% of the population had a disability. In response to the plight of unmet needs, the national House of Representatives declared a state of emergency, which led to agencies’ submitting reports on their activities with people with disabilities. Now, the government has more control, and professionals hope for agencies to be more coordinated.

Currently, the features of Teletón they mention when seeking funding, donations, or referrals is being transformed. The staff feel everything is changing. Still, the prominent messaging is about services families receive in the CRITs-the therapy sessions. The flag-bearers for change want to alter this messaging so consumers will not think going to the CRIT will produce a miracle.

When Teletón was formed, in 1979, its approach was rehabilitative. In 2010, with a change in leadership, it turned its attention to human rights. The organization articulated three principles: human rights, inclusion, and holism (attending to the whole person, taking into account mental and social factors, rather than only the physical symptoms of a disability). Services were expected to honor all three principles.

In 2015, leaders in Teletón recognized that, not only in Paraguay, but also in neighboring countries, services were not attending to these principles. Teletón staff reported that what they were offering families was far different from what they imagined they should be, following principles of human rights, inclusion, and holism, but they had no beacon to lead them to compatible practices. This lack of guidance produced discomfort, which, in turn, led the staff to look for suitable approaches.

Teletón leaders knew that other Teletones and Argentina were using highly clinical, traditional rehabilitation approaches to serving children with physical disabilities. During that time of “helplessness,” as they called it, the International Federation of Catholic Universities announced a master’s program at the Catholic University of Valencia (Universidad Católica de Valencia-UCV) on Holistic Services for People with Disabilities (Máster de Atención Integral a Personas con Discapacidad). UCV contacted the Catholic University of Asunción, looking for students to enroll.

Some staff members at Teletón enrolled in the master’s degree program, where they learned about the Routines-Based Model of Early Intervention for children birth-6 years of age with disabilities and their families13. This model (a) promoted the concept of child competence, which was aligned with the principle of human rights; (b) actively supported family decision making, which was also aligned with human rights; (c) advanced the importance of children’s participating fully in naturally occurring routines at home, school, and community, which was aligned with inclusion; and (d) assessed needs and planned interventions for the whole child and family, which was aligned with the principle of holism. Teletón leaders realized this model could be the route to reaching their idealized destination. In 2015, the organization began a pilot project to learn about and implement the model, with 7 professionals and 25 families.

In 2014, two of the three service directors at Teletón enrolled in the first cohort for the master’s degree program at UCV. The staff say these two pioneers “got hooked on family-centered practices.” When they returned to Paraguay, they found that their third colleague resisted the information.

This director, however, enrolled in the master’s program and visited Valencia and other early intervention centers in Spain that were implementing the RBM. Her interest in the model led her to return to Spain another three times. On one of those visits she met Robin McWilliam, the purveyor of the RBM4, and arranged for him to visit Paraguay.

In the meantime, another ambassador of the model, Margarita Cañadas, the leader of the UCV master’s program and an acolyte of McWilliam’s had visited Teletón Paraguay to provide training and technical assistance. She was surprised at the lack of space and facilities for families. Cañadas ran a model demonstration early intervention program at UCV called L’Alquería, which had impressed Sofia Barranco, the now-enthusiastic supporter of the RBM. She saw inclusive classrooms at L’Alquería, integrated therapy (i.e., therapists working with teachers, rather than pulling children out), and working with families on home visits. She also saw the L’Alquería early interventionists facing some of the same challenges Teletón professionals faced. According to the Teletón leaders, an important resource for Teletón was having McWilliam and Cañadas as mentors in the process, answering questions and providing guidance: “They respected all our personal processes, questions, and insecurities.”{McWilliam, 2016 #2394}{McWilliam, 2016 #2394}{McWilliam, 2016 #2394}{McWilliam, 2016 #2394}

Teletón invited McWilliam twice-once for a conference they hosted and once to work with the staff and visit the CRITs. At the conference, they became convinced that the model would address their priorities of inclusion, comprehensive family support (i.e., holism), and human rights. Cañadas was also a speaker at this conference, and she persuaded Teletón of the alignment of their priorities with the RBM. One leader said, “The model found us through Marga.” The second visit launched implementation of the model.

The live visit (as opposed to online video meetings) was designed to learn from him how to effect the different practices and also to have him provide guidance on how to move forward into implementation. He discussed various options, based on their priorities and resources and focused on the four stages of implementation articulated by the National Implementation Research Network3,4: exploration, installation, initial implementation, and full implementation.

It was also important to Teletón that McWilliam and colleagues actually saw the conditions they were working with, from the impressive CRITs in Asunción, Coronel Oviedo, and Alto Paraná to the heartbreakingly impoverished homes of some rural families they served. One of the leaders said, “There is no better way for you to understand us, than coming and seeing this.” On one home visit, McWilliam ended up helping a young mother adapt a chair for her son with cerebral palsy, so, for the first time, the boy could look out at the world and is mother did not have to carry him all day long.

The Teletón staff felt the visit made a scientific and technical contribution to their knowledge and optimism about the feasibility of implementation. In particular, McWilliam provided encouragement to the flag bearers-the 12 people who participated in intensive workshops with him. Barranco was surprised at McWilliam’s “empathy”; she repeatedly said, “He knows so much and has heard the same question a thousand times… and he always answers it with great patience and seeks creative solutions to help you solve problems, sometimes peculiar ones, due to our particular system.”

Teletón had the advantage of having moved towards interdisciplinary teams some years earlier. This meant that professionals worked in teams, as opposed to working in isolation, and they communicated with each other. This helped make the RBM, which focuses on the primary-service-provider teaming approach, feasible. As one leader said, “We were ready for change, and we were looking for this important role of families.”

Routines-Based Model

The model Teletón chose, the Routines-Based Model, has evolved over the past 17 years but with roots going back to 1985, when McWilliam and colleagues began research on child engagement17. Space precludes a detailed description of the model here, where we concentrate more on the case study of implementation by Teletón, but we do highlight six features of the model. Significantly, the RBM places a priority on the functioning of children in their daily routines and the support to regular caregivers to be children’s primary teachers or interventionists, in their roles as parents or classroom teachers.

Needs Assessment of Children and Families

To determine what to work on-what should be on the intervention plan-we conduct a Routines-Based Interview (RBI), which is an in-depth, semi-structured interview about the child’s engagement, independence, and social relationships in naturally occurring activities and events15. In addition to information about child functioning, the interview elicits family-level information, such as who their informal supports are, what they worry about, and what they would like to change in their lives. This needs assessment is different from professionals’ deciding on goals on the basis of tests or their clinical judgment.

Intervention Planning

The RBI produces 10-12 child and family goals. Family goals can be related to the child and his or her disability or can be for the parents’ well-being. This intervention planning is different from having only two or three goals or having only child skills for goals.

Service Delivery Methods

The RBM employs a primary-service-provider (PSP) approach, in which one person is allied with the family, partnering with them at every visit10,20. This PSP is supported by other team members from other disciplines who provide consultation through informal means, meetings, or joint visits with the family. This service delivery method is different from having different professionals working separately with the family.

Routines-Based Center Visits

Family-centered visits based on ensuring families had support were developed for the model to be completed in homes12,16. Visits feature a collaborative consultation approach with families, and this approach was adapted for consulting with children’s teachers in classroom settings. The most important adaptation for Teletón, however, was our guidance on how to make center-based visits follow the same principles as home visits: building the family’s capacity to meet their child’s and family’s needs (instead of thinking of the visit as the one intervention time in the week), addressing family-level needs (not only those related to the child), and letting families set the agenda (rather than having professionals decide on the topics for the visit).

Performance-Checklist-Based Training

A checklist exists for every practice in the RBM. Checklists serve three purposes: They define the practice, they provide a platform for feedback, and they provide implementation fidelity data1. After introduction to practices through workshops (called training in implementation science) that often include demonstration, early interventionists are trained (called coached in implementation science) through supervisory coaching19. In this coaching, implementers are observed, the checklist is scored, and the coach provides performance feedback. This training method is different from workshops only or feedback without well-articulated steps.

Summative Evaluation

In the RBM, we want to know whether we have been effective with children and families. To measure this success, we measure children’s functioning in everyday routines, their acquisition of individualized goals, and family quality of life. Children’s functioning is measured by having families complete the Measure of Engagement, Independence, and Social Relationships, which consists of functional skills organized by common home routines18. We measure acquisition of individualized goals through either goal attainment scaling9 or the Therapy Goals Information Form11. Finally, we measure family quality of life with the Families in Early Intervention Quality of Life Scale (FEIQoL)5,6.

This summary of the RBM presents only the major components. More detail can be found at www.eieio.ua.edu and at http://naturalenvironments.blogspot.com/2019/02/the-routines-based-model.html.

Implementation Plan

About one year after McWilliam’s visit, Teletón made a huge investment by sending María Asunción (Marisú) Pedernera García, the aforementioned occupational therapist, to complete an eight-month internship with McWilliam and his team at The University of Alabama. She joined Pau García Grau, postdoctoral fellow, and Catalina Morales Murillo, international intern and doctoral student, and others in the Evidence-based International Early Intervention Office (EIEIO). More Spanish than English was spoken in the EIEIO during this time. This internship allowed Pedernera to acquire in-depth knowledge of the model and to develop a draft implementation plan for Teletón.

When she returned to Asunción, Pedernera was quickly seen as the expert on the RBM and the natural coach. Although she had been in constant communication with Teletón leaders as she drafted the implementation plan, now it was time to see what really could be done.

First, each CRIT had different challenges and would require quite a different plan. Second, professionals were now actually listening to families and bumping into compassion fatigue2. They were becoming emotionally drained listening to families talk about their daily routines, which sometimes involved struggling for basic needs and surviving domestic violence. Professionals liked it better, before, when they didn’t have to hear these stories.

By the time Pedernera was appointed the coach, only one of the three directors who previously had been involved in workshops and implementation planning was still charged with RBM responsibilities. Having only two people to coach implementation of the model in four disparate CRITs was challenging. They are trying to empower one professional in each CRIT to be the RBM coach, but this requires time, and they have full caseloads. Because everyone, not only the coaches, is busy, building enthusiasm for or even compliance with the model, which requires time to learn and practice the practices is challenging. Few people want to take on anything more. This, incidentally, is a universal challenge across all RBM implementation sites, worldwide.

Although idiosyncratic plans were eventually drafted for each CRIT, all four of them first tackled the ecomap, the RBI, functional goal writing, and using the matrix. After the visits by McWilliam and Cañadas, Barranco and Pedernera provided training, which, in the RBM, is considered observation and feedback or coaching7. In the RBM, performance-checklist-based training is necessary, but some Teletón professionals resisted being observed and scored on checklists. This reaction occurs, sometimes, with professionals who are not accustomed to being observed, which is true of most early interventionists. In the model, we encourage coaches to persist with checklist training, because, once practitioners recognize how helpful and nonjudgmental the process is, they overcome their hesitation about this type of training, which is why we call it the gift of feedback. At Teletón, however, leaders and coaches have a high level of compassion for the staff and tend to respond with more empathy than commitment to the process. So checklist training on the RBI has not been implemented with fidelity.

The extent of implementation varies across CRITs. Some CRITs decided the model would be implemented with families of children up to 12 years of age; others with families of children up to 18 years of age (i.e., all families). In three CRITs, the model is implemented only one day a week, and, in the other, it is implemented every day, as seen in the following list:

Asunción CRIT: 32 professionals serving 120 families (1 day of the RBM per week)

Coronel Oviedo CRIT: 12 professionals serving 30 families (1 day of the RBM per week)

Paraguarí CRIT: 8 professionals serving 27 families (1 day of the RBM per week)

Alto Paraná CRIT: 14 professionals serving 315 families (all days of the week with RBM practices)

The Alto Paraná CRIT was established in 2016 and, from the beginning, it implemented the RBM; hence, its use of RBM practices daily. The other three CRITs, in contrast, have been implementing the model gradually.

In 2019, García Grau went to Teletón to provide training and technical assistance. The staff wanted in-depth information about demonstration to families, family consultation, functional goals, use of the matrix, and how to work with the family. They understood the importance of the RBI but were unsure how to make take that information forward into visits. This transition from needs assessment to visits is a common question; see https://naturalenvironments.blogspot.com/2019/07/what-happens-after-rbi.html.

García Grau visited each CRIT twice, presenting information, organizing role play, and demonstrating with families on the first visit. On the second visit, he observed professionals working with families and provided feedback. The staff said these visits made the model look practical and feasible. Furthermore, he articulated the scientific background to the practices in a way that was digestible to the staff. His own experience in learning about the model and adopting it in Valencia, where he had first encountered it, and being a native Spanish speaker was helpful for Teletón.

García Grau, who is a leader of the RBM and has been involved in its implementation in Alabama, USA; Australia; Portland, Oregon, USA; and Spain, was surprised at how much Teletón attended to the emotional reactions of the staff. Whereas in other implementation sites, the expectation is to deal with the situation and move on, in Teletón, coaches listened to employees’ concerns, validated them, and did not push them beyond their comfort zones. This responsiveness has slowed implementation and, owing to resistance to checklist-based training, has compromised fidelity to the model. The other force slowing implementation is the vocal minority resisting the model. In an organization that values different opinions and gives employees room to voice their opinions, the resistance by a few conservative staff members can impede implementation by early adopters and neutral adopters.

Formative Evaluation

To determine how well the model is being implemented, most RBM sites have data on our various checklists. At Teletón, they did collect Routines-Based Visit in the Clinic Checklist14 data in Asunción and Alto Paraná-two data points in 2018 and one in 2019. These data have not been entered on a spreadsheet or summarized, which reveals a lack of interest in formative-evaluation data. Although they are implementing the RBI with ecomap, they are not observing with the relevant performance checklist, owing to resistance by the staff.

The Teletón staff like the RBI for producing functional and family goals, but the follow through with routines-based visits is estimated to be very low. Professionals indeed talk about daily routines with families, but they are inconsistent about using family consultation to land on strategies, let alone demonstrate or help the family practice strategies.

The coaches have seen an increase in the number of professionals interested in implementing the model, including routines-based visits. A workshop held in August 2019 attracted volunteer participants from the Teletón staff, as well as professionals from other organizations. Some of the Teletón participants had been early critics of the model and were now interested enough to personally pay to receive more training on the model.

Conclusion

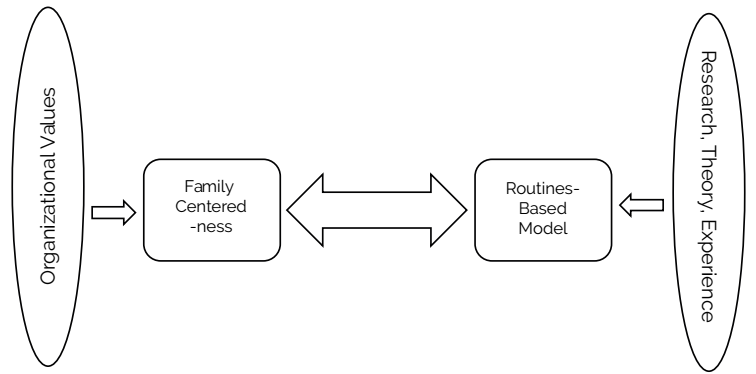

The story of Teletón’s implementation journey is a case study in the reciprocal effects of ideas and action, as shown in Figure 1. The organization had strong and clear values they imbued through all operations: holism, human rights, and inclusion. When leaders learned about family-centered approaches, primarily from Marga Cañadas, their need to change practices was awakened. Cañadas told them the RBM was the model that had well-articulated practices to put the concept of family centeredness into action. As the staff began learning how to listen to families carefully, to develop functional goals chosen by the family, and to try to make routines-based visits, their understanding and acceptance of family centeredness increased.

Source: Prepared by the authors (2019)

Figure 1 - Reciprocal relationship of idea (family centeredness) and action (Routines-Based Model)

The case of Teletón’s adopting the RBM is also an example of how adaptations are negotiated between the purveyor of the model and the implementers. For financial reasons, the organization could not move to home visits, where they would be able to see only three or four families a day instead of the eight families a day in the center. In addition, the conditions of families’ homes are also perceived to be a barrier, with some homes inaccessible by car and “conditions around the poverty situation.” Fortunately, the RBM already had developed procedures for center-based visits because of similar concerns in some European implementation sites. It is still a goal of Teletón to have ongoing home visits in the future. “Ongoing” home visits are distinct from occasional home visits in purpose: The purpose of the former is to support and build the capacity of the family to meet their self-identified needs; the purpose of the latter is to get to know the family better and, sometimes, to check on the family’s living conditions.

Teletón was correct to begin the implementation of the model with the RBI, because results in functional and family goals. Without good, meaningful goals, one cannot have good, meaningful visits. Owing to insufficient coaching resources, two gaps opened up. First, staff were doing RBIs without being observed and given checklist-based feedback. This has meant that RBIs might not be occurring with fidelity to the model and that we have no data one way or the other; checklists provide fidelity data. Second, training on routines-based visits has not happened. The staff have had such visits explained and demonstrated but they have not had systematic observation and feedback (i.e., coaching). These gaps demonstrate two features of strong implementation: The organization needs to assign enough resources to coaching, and performance checklists must be used for training. Teletón actually did reassign the primary coach to spend most of her time coaching, but the demand was too great for her to be able to coach everyone often enough.

One solution might have been to use a cohort approach, small groups are trained in sequence, rather than trying to train everyone at once. We have used the cohort approach in the Portland (Oregon) implementation site, and it works well: Earlier cohort members become available to train later cohort members. But it is a slow path to reach full implementation. This is a critical lesson about implementation of early intervention models, especially for large programs like Teletón and the Portland site. A distinction between true implementation or model adoption and superficial professional development, like workshops only, is that it requires the commitment of resources to coaching and it takes time. Almost all adopters of the Routines-Based Model have been working on 4- or 5-year implementation plans.

Finally, Teletón provides a lesson in the sort of cultural sensitivity needed in implementation of a model from elsewhere. At the same time, the case of this organization shows that a model adopted at scale, such as internationally, has to be flexible. Whether because of the Paraguayan culture or the organizational culture, the leaders and the purveyor were faced with two challenges. First, the RBI requires the professional to listen to details of families’ days. Many of the families Teletón serves are extremely impoverished and many mothers experience domestic violence. Paraguay has a high rate of domestic violence, especially in poor families, even compared to other Latin American countries8. When the professionals started hearing the horror stories of many families, they were emotionally affected. They probably also, in the backs of their minds, were aware these stories were not new; they just had not been heard before. The second challenge related to cultural sensitivity is that the culture at Teletón is to look after the staff, especially the staff’s feelings. Leaders ensured staff knew they could talk about their feelings of sadness, empathy, and compassion fatigue. From an implementation standpoint, they will have to guard against allowing staff to stop listening to families. Without a structure to monitor the fidelity of the RBI or the routines-based visits, it will be difficult to ensure staff are still listening to families.