INTRODUCTION

It is known that universal health systems are important to improve the life conditions of populations and, at the same time, to tackle significant injustices in different countries 1 . The training and distribution of health professionals, generally focusing on doctors, has been one of the critical issues considered in strengthening health systems and building equity 2 .

One of the most recent landmarks in the international discussion about the training and distribution of health professionals was the 2010 document from the World Health Organization (WHO) entitled Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention 3 , which addressed four possible dimensions to increase the access to health professionals and retain them in remote regions. Among these dimensions are educational initiatives, where the actions highlighted include recruiting students originating from rural areas and encouraging placements in rural areas 4 .

Some of the authors who have written on the training of doctors have strongly criticized the way in which this is currently being performed, including Ritz et al . 5 . These authors argue that the medical school is a mechanism for perpetuating itself because it basically aims for its own sustainment in saying to society that it produces a qualified and competent doctor. A landmark in this analysis is the publication that evaluated one hundred years since the Flexner Report, in which a commission of medical education specialists from different countries proposed the need for a new reform movement in the area, so that training would become effectively based in health systems 6 .

Although the role of the Flexner report should be understood in the context of the beginning of the previous century, the new reform movement criticizes the sub-specialized and hospital-centric training and argues that training cannot be disconnected from the social determinants of health and, therefore, the organization of the local health system. Once again, it criticizes the medical school that aims only to reproduce itself, but does not converse with other relevant stakeholders in health and, principally, does not concern itself with the way that its graduates act in the health services 6 .

In harmony with this movement, new proposals arose and were consolidated for modifying medical training, represented by international consortiums that, on principle, respect autonomy and local characteristics. Obviously, this is not the first time that changing medical training has been discussed, as it is possible to list various previous movements. In the scope of the Americas, for example, movements have been recorded since the 1950s and 1960s, captained by the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), which aims to meet the social demands for doctors with training appropriate to health systems.

One of the examples that is highlighted in these movements is a working group promoted by PAHO to prepare minimum requirements for creating medical schools 7 . The participants extrapolated the initial objectives of the group and ended up also seeking strategies to change existing schools. This resulted in one of its important assumptions, which is (in Spanish): “El fin último del sistema de formación de recursos humanos para la salud, no es formar profesionales, sino mejorar la salud de la población”. (“The end purpose of the system of training human resources for health, is not to train professionals, but to improve the health of the population”) (p. 265).

Accordingly, the issues analyzed in this article cannot be characterized as a recent discussion, although this debate has advanced and retreated at different times (or, at least, undergone a certain stagnation). At the same time, the change in training has gained new outlines in the recent context, for example with the consortiums already cited, guided by the idea of social accountability in medical education.

Among these consortiums, there is noteworthy output from the Training for Health Equity Network 8 and the Global Consensus for Social Accountability for Medical Schools 9 , which bring together medical schools from different continents and seek accreditation formats for schools that come to be declared as socially accountable. In the most recent scope specific to the Americas, PAHO aims to encourage new changes among the schools, with a landmark a meeting being held in Brazil in 2014, which generated the report (in Spanish) La misión social de la educación médica para alcanzar la equidad em salud 10 ( The social mission of health education to achieve equity in health ).

Social accountability in medical education – translated as “responsibilidade social” in Brazil – and also known by the term “social mission” (“missão social”) – refers to the institutional responsibility to guide training, research and in-service activities to meet health needs, with the priority focus on areas where access is difficult 8 . This concept arises from the perception that aiming for health is also to aim for social justice, understanding that the medical school must have the obligation to direct training, research and extension activities to address the priority health concerns of the community, for the region or for the nation in which it resides 11 .

These definitions, therefore, lead to the concept of a medical school in close harmony with the health system, which some authors describe in specific experiences as being a health-school system 12 . In schools that adopt the perspective of social accountability, it is argued that they must make an explicit contribution to the health system, demonstrating, for example, that the doctors trained have a positive impact on the health indicators of their communities 13 .

The Global Consensus for Social Accountability for Medical Schools 9 lists ten directives for action from the perspective of social accountability: anticipating society’s health needs; partnering with the health system and other stakeholders; adapting to the evolving roles of doctors and other health professionals; fostering outcome-based education; creating responsive and responsible governance of the medical school; refining the scope of standards for education, research and service delivery; supporting continuous quality improvement in education, research and service delivery area; establishing mandated mechanisms for accreditation; balancing global principles with context specificity; defining the role of society.

Even the concept of social accountability is under debate, there being, for example, the formulation from Boelen et al . 14 , in which the differences between accountability , responsibility and responsiveness are discussed. For these authors, these three terms are adopted to describe the gradient of differences and capacity for change between the schools, where the term accountability – or “responsibilidade social” as the present authors translate it in Brazil – would indicate the most advanced stage that a Medical course could reach.

The school characterized by responsibility would be committed to social well-being and the education of good doctors. At another level, the school adopting responsiveness aims to respond to the health priorities in a location: training doctors with specific competencies and with an eye on professionalism. Finally, the school with accountability works collaboratively with governments, health organizations and society, aiming for a positive impact on the health of people, being capable of demonstrating that its work is relevant, of high quality, equitable and cost-effective 14 .

Therefore, the social accountability term translated by the present authors into Portuguese as responsabilidade social aims for greater coverage, but must be used with care, so as not to give the appearance of newness to something that aims to maintain conservative structures or the status quo 15 . It is exactly from this perspective that Ritz et al. 5 propose critical reflexivity social accountability: originating from the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, a medical school considered to be socially accountable, which participates in international consortiums, the authors analyze in what way the term “social accountability” is becoming an “umbrella” that has come to cover conservative guidance matrices, which aim only to reproduce the medical school in patterns similar to the reforms influenced by the Flexner Report 6 .

Surpassing this perspective means reflecting on the contradiction of processes where the actors at medical schools, who originate from the most privileged classes, plan the needs of the working classes. Having this in mind, it is proposed to continue to use the term social accountability, but include the “critical and reflexive” view to establish initiatives such as: constantly re-examining the processes and the role of each stakeholder in them; contextualizing the local social, political and cultural situation; making social accountability a substantive enterprise, aiming to tackle injustice and evaluating its impact; sharing the power between the medical school and other stakeholders.

Despite the growing international literature on the theme and the initiatives in the region of the Americas, national references on social accountability are still insufficient. One of the few is the report mentioned above, with regard to an event held in Brazil in 2014 on the social mission 10 . There is also the translation into Portuguese of the initiative of the Global Consensus for Social Accountability for Medical Schools from the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (Faimer) 16 .

In the national arena, there are various well-qualified landmarks in the debate about medical training, and it is not intended to describe them in this article. Among the initiatives can be cited the Health Care Training Project (IDA – Integração Docente Assistencial) of the 1970s and the “New Initiative in Health Professional Education: United with the Community” (UNI – Uma Nova Iniciativa na Educação dos Profissionais de Saúde: União com a Comunidade) in the 1990s, which advocated greater integration between teaching, service and community 17 . Another society initiative in the 1990s was the National Inter-institutional Commission on Medical Education Evaluation (Cinaem – Comissão Interinstitucional Nacional de Avaliação do Ensino Médico), consisting of different entities, most medical corporations, and which extrapolated the scope of the evaluation and proposed changes on four fronts (management, in-service placement, professionalized training, and evaluation) to transform medical education 18 .

The most recent initiatives for changing training have been in the government sphere 19 , such as the National Reorientation Program for Health Professional Training (Pró-Saúde – Programa Nacional de Reorientação da Formação Profissional em Saúde), the Education Program for Working in Health (PET-Saúde – Programa de Educação pelo Trabalho em Saúde) and the Program for Valuing the Primary Healthcare Professional (Provab – Programa de Valorização do Profissional da Atenção Básica). However, the most wide-ranging recent initiative has been the More Doctors Program (MDP) (in Brazil, PMM – Programa Mais Médicos), launched in July 2013, which has been characterized by legal provisions and actions involving the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education to change training 20 .

The proposals in the scope of training for the MDP were for a new regulatory landmark in Brazilian medical education, aiming to reorganize the process for opening Medical courses and medical residence places, prioritizing health regions with the weakest relationship between places and doctors per capita, but which have health service structures capable of offering fields of practice appropriate to the training. Therefore, by virtue of the MDP, various Medical courses were created in the interior of the country. Law 12.871/2013 established new National Curricular Directives (DCN – Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais), setting the conditions for opening and operating courses to effectively implement them, which were published in 2014 21 .

Considering this recent context of introducing new modifications to medical training, the aim here is to analyze the perception of Medical students, on courses created before the MDP and on courses created because of this program, about the social accountability of the medical school.

METHODOLOGY

This is a qualitative study, guided by the theories of social representation. Four Medical courses at federal Higher Education Institutions (HEI) in the Northeast Region were selected for this research. This included two created under the More Doctors Program, with campuses in the interior of their states. The other two had been operating for at least 60 years, corresponding to courses in the state capitals, from the same HEI as the course in the interior.

From the analysis of the curriculums of these courses it could be seen that the older courses had isolated subjects involving primary healthcare placements and that the predominant methodology was oral transmission (lectures). On this basis, these have been called “traditional”. For the courses created under the More Doctors Program, the curriculum was structured as proposed in the DCN of 2014, with active teaching/learning methodologies by means of tutorials and weekly and longitudinal primary healthcare placements. Considering these characteristics, these courses have been called “new”.

The research took place between July and September 2017, with students in the seventh semester of these courses being invited to participate. This semester corresponds to the stage that the first intake on the “new” courses had reached, being, therefore, the most advanced with which it was possible to develop the research instruments. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Beings of Faculty of Health Sciences in the University of Brasília under Opinion no. 1.852.717.

Among the 198 students registered on the seventh semester of this course, 159 were present in the lesson on the day on which the research was presented. Of these, 149 agreed to participate voluntarily in the study, being 68 from “traditional” courses and 81 from “new” courses. Initially, the participants answered a sociodemographic questionnaire, based on questions similar to those applied in the National Student Performance Examination (Enade – Exame Nacional de Desempenho dos Estudantes). They then completed a free recall script, in which they cited three words that occurred to them immediately in relation to the term “social accountability”. Next, the students numbered, in order of importance, written words or expressions to prioritize the items 22 , 23 .

The data from the sociodemographic questionnaire were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 23.0. Univariate analysis was conducted and the frequency distribution constructed. The words cited in the free recall script were analyzed using the Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires software (Iramuteq), which uses word tables to enable the social representation structure to be identified. The prioritization was also processed using the software, so as to reinforce or re-evaluate the placement of these terms.

In this way, categories and words were prioritized in coherence with the analysis performed from the viewpoint of the qualitative research, aiming to summarize the most significant structures presented by the interviewees and perform a summary effort without suppressing the richness of the information 24 . The analysis of the students responses was conducted by means of the theory of social representation 25 , using the complementary theory of the central nucleus 22 .

Social representations are symbolic elements that individuals express through the use of words and gestures. They can also be defined as messages mediated by language, constructed socially and necessarily anchored within the context of the individual who produces them 24 . When the representation of an object is created, the subject is also represented. When the subject expresses an opinion on an object, it is assumed that they make a contribution to developing a representation 26 .

For the objectives of this research, the concepts of central nucleus and peripheral nucleus as defined by Sá 27 were also used. The central nucleus is marked by the collective memory, reflecting the historic, sociological and ideological conditions of the group; consisting of a common, consensual base, collectively shared in the representations, providing homogeneity to the social group. It is stable, coherent and resistant to chance, thereby ensuring the continuity and the consistency of the representation; it is relatively insensitive to the social context and immediate material in which the representation manifests itself. While the peripheral nucleus permits individual and historic experiences to be integrated; it supports the heterogeneity of the group and the contradictions; it evolves and is sensitive to the immediate context.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The questions for profiling the participants in this step are shown in Table 1 , split between participants in the “traditional” schools and “new” schools. It can be seen there are a series of similarities between the groups with regard to the sex, civil status, secondary school education and motivation for studying Medicine. At the same time, there are notable differences in variables such as age, family income, parents’ educational level, current employment, entry through affirmative action policies, the presence of doctors in the family, and the reason for choosing the HEI.

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic profile of the students participating in the research in “traditional” and “new” schools. Brazil 2017

| Type of Medical school | “Traditional” school (N = 68) | “New” school (N = 81) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 33 | 48.5 | 42 | 51.9 | ||||

| Male | 35 | 51.5 | 39 | 48.1 | ||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 20 to 24 years old | 50 | 73.6 | 49 | 60.5 | ||||

| 25 years old or older | 12 | 17.6 | 31 | 38.3 | ||||

| No response | 6 | 8.8 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Civil Status | ||||||||

| Married | 1 | 1.5 | 9 | 11.1 | ||||

| Single | 66 | 97.1 | 69 | 85.2 | ||||

| Stable union | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 3.7 | ||||

| Mother’s educational level | ||||||||

| None | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Primary school | 6 | 8.8 | 15 | 18.5 | ||||

| Secondary school | 16 | 23.5 | 22 | 27.2 | ||||

| Higher education | 27 | 39.7 | 26 | 32.1 | ||||

| Post graduate | 19 | 27.9 | 17 | 21.0 | ||||

| Father’s educational level | ||||||||

| None | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | ||||

| Primary school | 6 | 8.8 | 22 | 27.2 | ||||

| Secondary school | 22 | 32.4 | 24 | 29.6 | ||||

| Higher education | 26 | 38.3 | 24 | 29.6 | ||||

| Post graduate | 13 | 19.1 | 9 | 11.1 | ||||

| Family income (minimum salaries) | ||||||||

| Up to 1.5 | 8 | 11.8 | 11 | 13.6 | ||||

| 1.5 to 3 | 8 | 11.8 | 16 | 19.8 | ||||

| 3 to 4.5 | 9 | 13.2 | 15 | 18.5 | ||||

| 4.5 to 6 | 9 | 13.2 | 15 | 18.5 | ||||

| 6 to 10 | 19 | 27.9 | 8 | 9.9 | ||||

| Over 10 | 15 | 22.1 | 16 | 19.8 | ||||

| Financed by government program | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 14.7 | 7 | 8.6 | ||||

| No | 58 | 85.3 | 74 | 91.4 | ||||

| Working | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 8.8 | 12 | 14.8 | ||||

| No | 62 | 91.2 | 69 | 85.2 | ||||

| Entry through affirmative action policy | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 | 27.9 | 37 | 45.7 | ||||

| No | 49 | 72.1 | 44 | 54.3 | ||||

| Predominant secondary education school | ||||||||

| Private | 47 | 69.1 | 56 | 69.1 | ||||

| Public | 21 | 30.9 | 25 | 30.9 | ||||

| Doctor in the family | ||||||||

| Yes | 11 | 16.2 | 22 | 27.2 | ||||

| No | 57 | 83.8 | 59 | 72.8 | ||||

| Principal reason for choosing Medicine | ||||||||

| Family influence | 3 | 4.4 | 4 | 4.9 | ||||

| Labor market | 16 | 23.5 | 15 | 18.5 | ||||

| Professional appreciation | 15 | 22.1 | 10 | 12.3 | ||||

| Vocation | 34 | 50.0 | 52 | 64.2 | ||||

| Principal reason for choosing the HEI | ||||||||

| Ease of access | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.5 | ||||

| Free entry | 15 | 22.1 | 34 | 42.0 | ||||

| Proximity | 5 | 7.4 | 14 | 17.3 | ||||

| Quality | 46 | 67.6 | 25 | 30.9 | ||||

| Only one offering a place | 2 | 2.9 | 6 | 7.4 | ||||

Source: The authors.

A similarity between the groups relates to the type of school at which the student received secondary education: in both groups, the number is about 30% of students originate from state schools and around 70% from private schools. The Quotas Law 28 stipulated that HEIs must have a percentage of 50% coming from state schools in the year 2016. For the year of entry of the students in this study (2014), this percentage had to be at least 25%. It is considered, therefore, that this proportion is in agreement with the provisions of the Law for all of the institutions participating in this research. However, Ristof 29 argues that this percentage is still insufficient; the author questions the goal of achieving only 50% of places for entry from state schools, given that Brazilian secondary education is essentially delivered by the state, corresponding to 87% of student registrations.

A difference to be highlighted relates to the entry by affirmative action policies, understood to be “[...] special measures that aim to eliminate the imbalances between determined social categories until they are neutralized” (p. 844) 30 . For this purpose, it is necessary for effective measures to be taken in favor of the categories that are found to be disadvantaged. Thus, the affirmative action policies bring the prospect of eliminating historic inequalities, aiming for equality of opportunity for socially excluded groups and populations 31 .

For Haas and Linhares 30 , the objectives of the affirmative action policies are: to combat the discrimination that happens in certain spaces in society; to reduce the inequality that affects determined groups; to achieve social transformation; to enable access to the school and to the labor market; to integrate different social groups in the existing spaces, valuing cultural diversity. To Dias Sobrinho 32 , the greater purpose for affirmative action policies is to promote social inclusion of some marginalized groups, such that these policies often end up collaborating for the development of some peripheral regions.

For Ristoff 29 , it is important to prepare a pathway so that more aggressive inclusion policies become politically viable. At the same time, Haas and Linhares 30 argue that extending the affirmative action policies is only possible through open discussion with the academic community, which they argue plays a fundamental role in the production of knowledge and the delivery of social needs. At this point, it is worth highlighting the context in which the “new” schools were created: as Reuni states, an important phenomenon in Brazilian higher education has been the increase in financing for public institutions 33 .

Therefore, it is possible to argue that the new schools have had a more favorable context for establishing the affirmative action policies by virtue of the expansion of higher education. It is also a suggested role for the More Doctors Program, considering that, for authors like Nascimento 34 , the new Medicine curricular directives provide a favorable context to use affirmative action policies in a school created on a new HEI campus.

This finding can be reinforced by the fact that the schools created by virtue of the More Doctors Program are, in this study, HEIs that have adopted their own affirmative action policies, for example, the Regional Inclusion Argument (AIR – Argumento de Inclusão Regional) 34 . The AIR involves increasing the mark in the Unified Selection System by up to 20% for the students. To obtain this, they must have completed primary education and studied in secondary education in normal schools, on-site, in the micro-regions where the HEI campuses in the study are located. Nascimento 34 views this as a successful policy, having demonstrated that students coming from the regions covered do effectively enter the course.

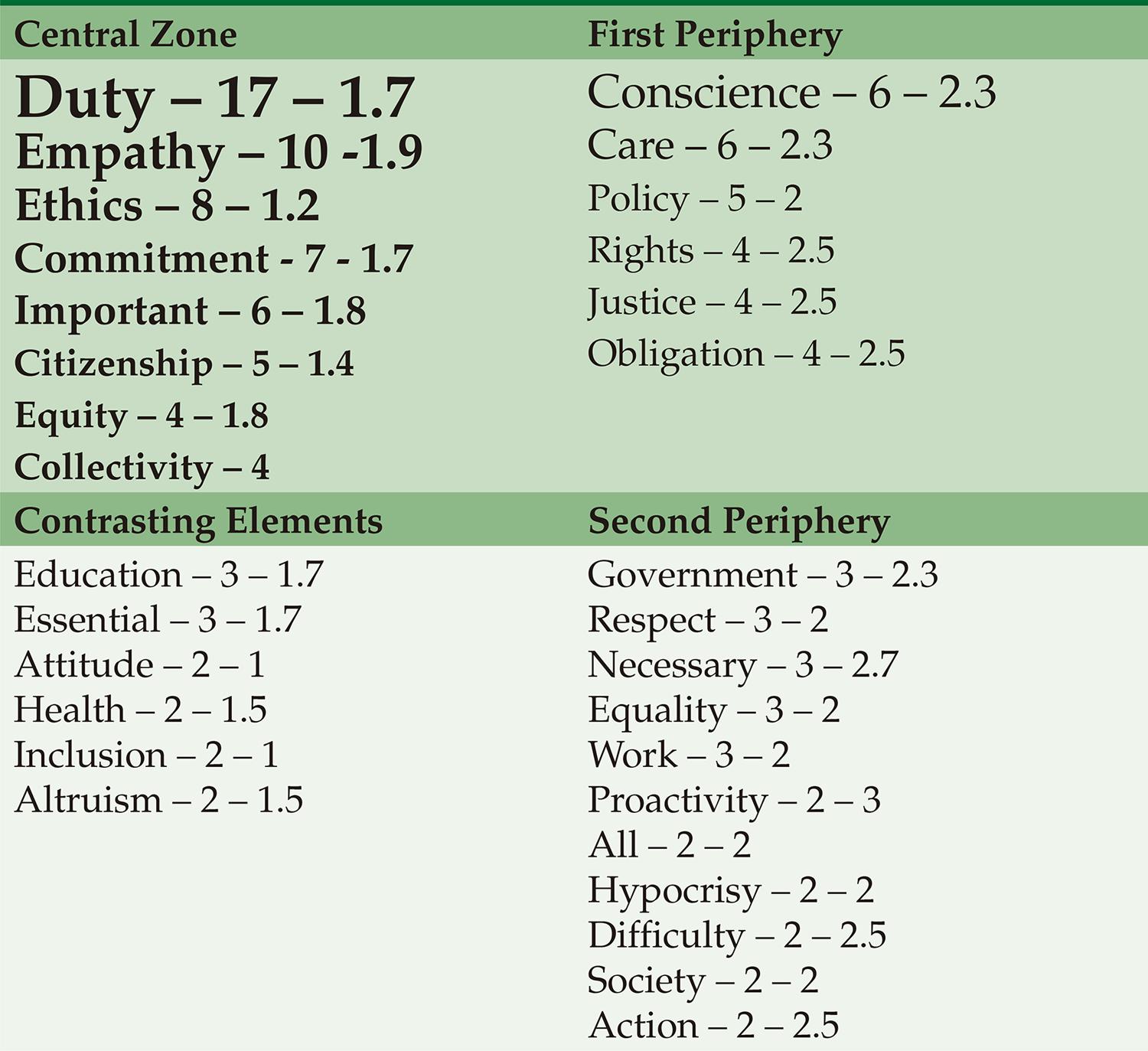

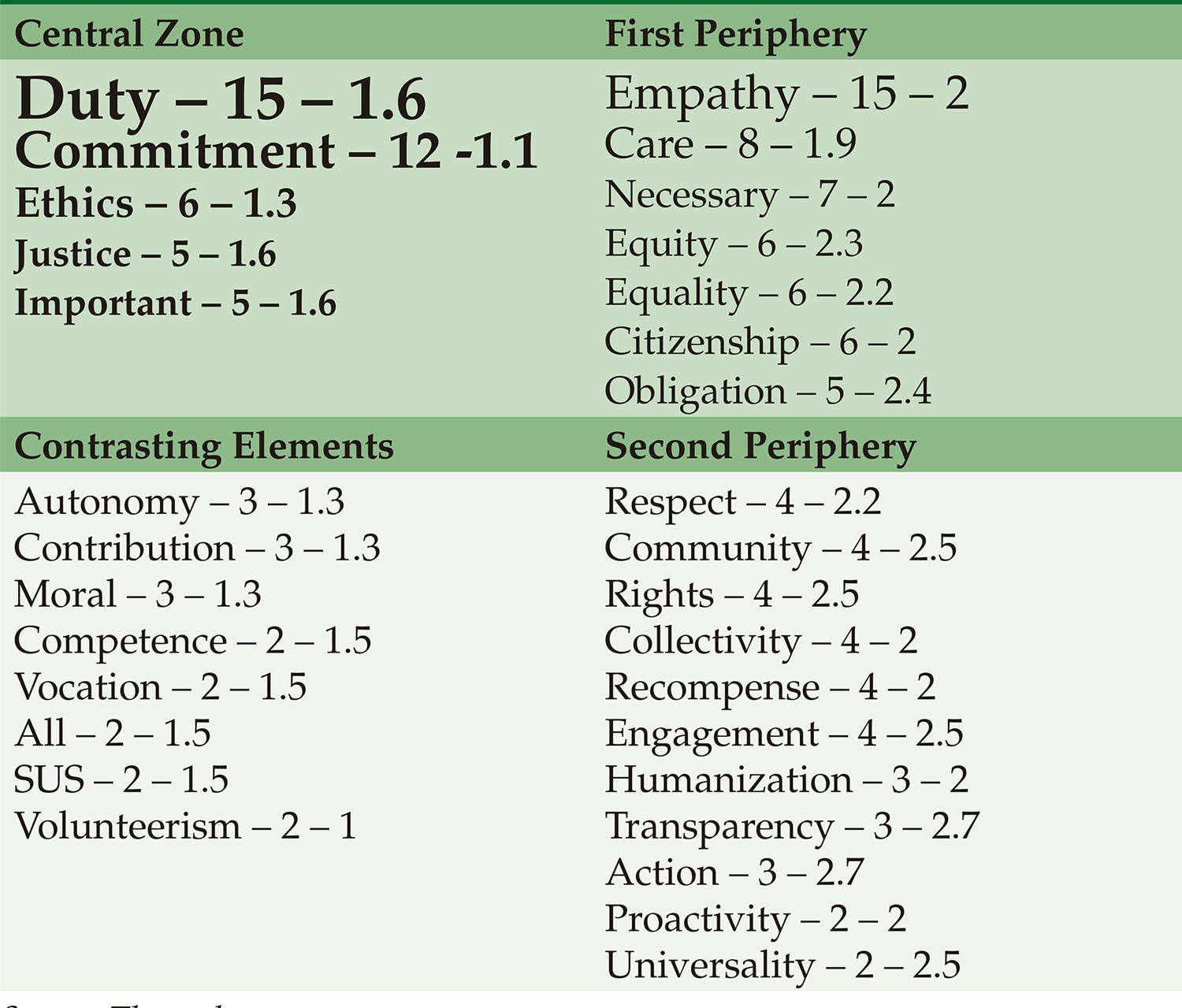

Continuing the analysis, with regard to the free recall instrument completed by the students, the results are presented in Figures 1 and 2, which summarize the findings from the free recall and the prioritization of the items at the time at which the participant in the research was presented with the term “social accountability” for the “traditional” course ( Figure 1 ) and “new” courses ( Figure 2 ).

Source: The authors.

FIGURE 1 Prototypical analysis of the terms recalled by the students of the “traditional” Medical courses when questioned about “social accountability”. Brazil, 2017

Source: The authors.

FIGURE 2 Prototypical analysis of the terms recalled by the students on the “new” Medical courses when questioned about “social accountability”. Brazil, 2017

The upper left quadrant shows the most frequently and promptly recalled words, being indicators of the central nucleus of the representation. The upper right quadrant is the first periphery, where the words have high frequency although they were not so promptly mentioned. The bottom left quadrant corresponds to the contrast zone, with low frequency elements, put promptly recalled, and the bottom right quadrant is the second periphery, with low recall and frequency 35 .

For the purpose of analysis, this work focused mainly on the terms of the central nucleus, first periphery and contrasting elements, considering the relevance of the terms to the training for the social representations of the Medical students. In both groups, that is, in the central nucleus for both the “traditional” and “new” courses, the most prominent term is “duty”, which indicates the recognition, by the students, that the doctor needs to have a degree of involvement in society.

What can be discussed on the basis of this understanding is to what extent the idea of duty transmits only the student’s individual perception, rather than a collective perspective, the view of the medical school as an actor integrated in a society. Thus, there is in common to both the groups, a possibly limited understanding of social accountability. Considering that they are public university students, there is a possible notion that they must return to society the specific public investment made during their training. Even so, in studies conducted with students in the next stage of the course, the internship, it was demonstrated that only 10% of the students in the final stage of the course considered working solely in public services. And the number that want to work in small municipalities is even less: 5% 36 .

The findings were similar to those from a study conducted with students of Medicine, Psychology and Dentistry, in which 80% seek to work in private consultancy, although many judged that it will be necessary to work in the public sector 37 . For the authors of the study, this vision is related to the construction of an image during the training in which the liberal-private perspective is privileged and the implications of the relationships between public and private in the Single Health System (SUS – Sistema Único de Saúde) is not discussed, which ends up not contributing to the real understanding and acceptance of citizenship.

Even so, the term “citizenship” is highlighted by both the groups, principally by the group of “traditional” schools. In this group, the term is in the central nucleus, suggesting that this is more consolidated, while in “new” schools it appears in the first periphery. This perception effectively references a collective society construction and has been prominent since the preparation of the National Curricular Directives of 2001, which advocate that the course has a commitment to citizenship such that the structure includes values directed towards it 38 .

Thus, the term is present in the new DCN of 2014, but not with such prominence to be compared with other terms that grow substantially in the number of citations. While, according to Rocha 15 , there is an increase in different articles for “competences”, for “citizenship” only a slight increase can be seen, being included at four points (in 2001 it was cited twice). Thus, it suggests that, even as a response to the movements for change at the start of the 2000s, the social representations of the Medical student were incorporated in the notion of “citizenship”, at least for participants in this study.

Nogueira 39 argues that the arrival of the DCN in 2001 occurred in a context of questioning the technical-scientific model of medical training, with new proposals more directed to an ethical-humanist project than intended in the previous model. Thus, it is possible for the medical schools to value terms such as “citizenship” in curricular reforms that occurred at the start of the XXI century, as well as its influence on the schools created by the More Doctors Program.

Another similarity relates to the use of the term “ethics”. Almeida et al. 40 observed that the students had better knowledge of the Medical Code of Ethics (CEM – Código de Ética Médica) than the teachers, and both groups considered the subject of ethics extremely important, despite having little involvement in or discussion of the subject. In addition, in discussing examples given of “bad” teachers who did not observe the CEM principles, it was observed that the model of these teachers could interfere negatively in the training of the student.

Even so, it can be seen that the education on ethics in Brazil tends to be very theoretical, not very humanist and treated as a specialty, with an individualistic profile, centered on the hospital 41 . In this study, in comparing the curriculums of Brazilian and Cuban medical schools, the authors stated that the discussion about ethics takes place in a more continuous way in the training in Cuba. Despite this, it evaluates that there has been an increase in the quantity of subjects that address ethical issues in Brazilian curriculums 42 , such that the focus given to the term in both of the groups suggests there is also an influence from the DCN of 2001, which advocates including ethical content in the structure of the Medical degree course. This proposition was maintained in full in the DCN of 2014. 15 .

Having highlighted the similarities, the analysis of the differences between the groups will now be discussed. At this time, the prominence of three terms cited by the students of “new” schools can be seen: “commitment”, “justice” and “SUS”, principally in the first periphery and in the zone of contrasting elements. For the group from the “traditional” schools, a term highlighted in the context of this debate is “conscience”.

One of the probable reasons for “commitment” being prominent in the “new” schools is the frequency with which the term appears in documents such as the Global Consensus for Social Accountability for Medical Schools 9 . In this document, commitment is discussed in different dimensions: the professional, serving in areas of need; the school, in working with other stakeholders in the health area; the different stakeholders regarding the principles and values of social accountability; the faculty and the students with the community. Thus, evidently, the term “commitment” refers to a more collective dimension than the terms addressed previously, and may represent an advance arising from the experiences only made possible in the courses implemented because of the More Doctors Program.

This perception of the social representations is reinforced when the term “SUS” appears cited only by the students of the “new” schools. Now, as training centered on the health system is advocated for the more recent reforms in medical education 6 , the first step for the students to recognize this perspective is to understand the correlation between social accountability and the Single Health System (SUS). So much so that on analyzing the experience of an innovative school, Melo et al. 43 reference the idea of longitudinal experience in the SUS, in training sensitive to the realities of the health system.

Similarly, the other consortium of schools cited in the area of social accountability, TheNET, also uses a term cited by the students of the “new schools” – “justice” – which in the case of this consortium appears when they cite their principles, including the goal of social justice. The concept of confronting injustice is directly connected to the discussion of the social determinants of health 1 , and in the scope of this work it is worth highlighting that the discussion of these determinants has only been incorporated in a definitive manner in the DCN since 2014 15 .

Therefore, the appearance of terms such as “commitment”, “SUS” and “justice” among the students of the “new” schools appears to signify the perspective of social accountability, even if it is a concept insufficiently implemented at national level. Adding this perception to the analysis of the profile of the students from the different schools, it can be stated that the greater incentive for the affirmative action policies and a perception more in the collective context of social accountability are possible effects of the proposals presented in the More Doctors Program.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The fact that there is little national literature available on social accountability, even though Brazilian schools have developed experiences consistent with this concept, suggests that there is still not a wide understanding what this movement means to the medical schools and, consequently, still less to the students. Despite this, the appearance of the term “SUS” among the students of the “new” schools is noteworthy and, therefore, an important opportunity for these courses to value the relationship with the health system.

In addition, on analyzing the different social representations among students of “traditional” and “new” schools, important signs can be seen of how the students of “new” curriculums are forging a new path, closer to that advocated as social accountability, which is reflected in terms such as “commitment” and “justice”. It can be appreciated that the modifications in the training introduced by the More Doctors Program has an important role in these changes.

It is also stressed that this analysis, as it was developed in the context of the social representations of the Medical students about social accountability, make a very specific separation between the specific context of the recently created schools and the “traditional” schools studied. It is necessary to observe how these experiences behave in a wider manner, including in the evaluation mechanisms, in the institutional or process context, including the proposals in the More Doctors Program. Therefore, other elements are required for this debate, that can be developed in new studies with different research instruments.

The changes to medical training proposed by the More Doctors Program has been a controversial subject of debates about its repercussions. Despite the disagreements, the arduous effort that many teachers are making for the country must be praised, in regions that previously did not have Medical courses, to teach the profession from the perspective of social accountability, this being a subject that needs to be pursued in the development of the teacher. These examples could be explored with the radicalism necessary to strengthen the Single Health System.

texto em

texto em