INTRODUCTION

Professionalism has become increasingly acknowledged as an important component of medical training (1), essential in the physician’s role in society (2). In 1999, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Medical Specialties adopted professionalism as one of the core competencies to be developed by physicians. The other competencies are: interpersonal and communication skills, practice-based learning and development, patient care, medical knowledge and systems-based practice (3). In 2013, the ACGME and the American Board of Pathology formulated 23 of its 27 milestones, of which six were dedicated to professionalism (4). In 2017, the ACGME program about professionalism was updated (3).

Despite its relevance to generalist and specialist medical training, there is no homogeneity as regards the concept of professionalism, which hinders its consolidation and standardization of strategies that encompass it as a component of the formal curriculum, as well as of the hidden curriculum (5). Although not formally taught, the hidden curriculum is responsible for behaviours and role modelling (6). It is therefore imperative that physicians and preceptors also shape the professional behaviours that they are trying to teach (5). Actions in this regard, however, demand a clear understanding of the dimensions to be incorporated into medical professionalism.

In view of the relevance of this theme to specialist medical training and of the lack of uniformity in the conceptual understanding of the term medical professionalism, the following questions emerged: what does the specialized literature understand by medical professionalism? How is professionalism being developed in the training of the resident physician? Therefore, this integrative review proposes to succinctly and systematically gather the information available in scientific productions about the concept of medical professionalism and its application in medical residency programs.

METHODS

In order to obtain a synthesis of the results from relevant and globally recognised studies, the method of integrative literature review was adopted (7). The search was guided by the question: how has the construct of medical professionalism been defined by scientific literature and how has it been developed in the training of specialists?

The survey was conducted in May 2018, consulting the electronic bibliographic databases EBSCO host, Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (Lilacs) and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline) via PubMed for the period from 2013 to 2018. The descriptors used were obtained from the Health Science Descriptors (DeCS) or from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). In English they were: Professionalism (DeCS and MeSH), Education, Medical (DeCS), Education, Medical, Graduate (MeSH), Internship and Residency (DeCS and MeSH). The Boolean expression AND was used, always crossing the first descriptor with one of the last three. In the Medline database, the English descriptors were used. In the other databases, the search was conducted with the descriptors in English and their corresponding terms in Portuguese. Observation studies were included (cohort, control case and cross-sectional studies) indexed in the last five years in the selected databases that answered the research question. Opinion articles, editorials, letters to editors and comments were excluded.

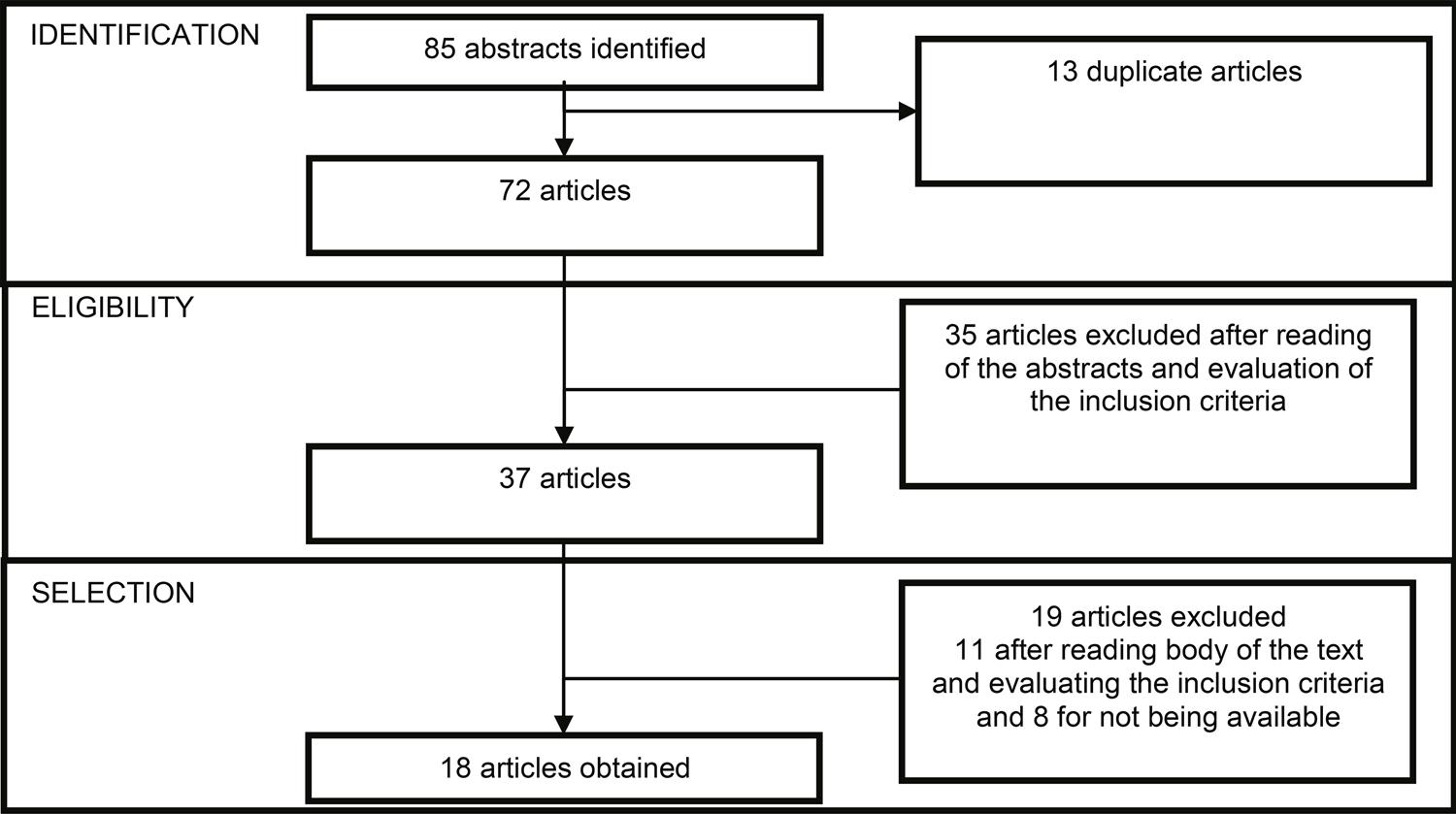

Eighty-five articles were found, 13 of which were excluded as duplicates through the Mendeley platform. Of the remaining 72 articles, 35 were excluded for not answering the research question. Of the 37 articles selected through reading of the abstracts, eight were not available in their entirety, leaving 29 articles. Following the complete reading of all the articles for the definitive selection, 11 were eliminated. Of those publications, six failed to correspond to the research objectives and five were opinion articles. The flowchart showing how the articles were selected for the integrative review can be found in Figure 1.

Three thematic categories were ascertained: (a) professionalism: multidimensional construct; (b) teaching of professionalism: role modeling and of the curriculum; (c) evaluation of professionalism: multiple strategies in the curriculum. To facilitate the data collection, an instrument was developed that contained author, year of publication, the concept of professionalism, domains and modes of teaching and evaluation of professionalism. The data were groups according to Chart 1.

CHART 1 Distribution of the articles analysed according to author, year, definition of professionalism, domains of professionalism and mode of teaching and evaluation.

| Year/Author | Definition of professionalism | Domains of professionalism | Mode of teaching and evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 / Kesselheim et al. (8) | Virtue intrinsic to the practice of medicine | Humanism; integrity; excellence; compassion; altruism; respect; empathy and commitment | Case studies, hidden curriculum, feedback |

| 2015 / Cummings et al. (9) | Not defined | Not mentioned | Taught through conferences, simulation and discussion of clinical cases. Not evaluated. |

| 2015 / Jameel et al. (10) | Unwritten social contract between the physician and society (2). Acquisition and maintenance of competence by means of career and values such as honesty, integrity, ethics, responsibility and altruism (2) | Confidentiality, responsibility, respect for others, honesty, relations with patients, care, altruism, relationship with others, management of conflicts of interest | Feedback, case studies. OSCE multiples used in the evaluation, to evaluate domains, and written evaluation. |

| 2015 / Khandelwal et al. (11) | It is one of the six competencies of the ACGME; own definition not mentioned | Responsibility, self-control an adaptability; relations with the university, students, preceptors and patients, medical principles; relationship with other members of the health team | Workshop, an inverted classroom program which focuses on the application of principles of professionalism to challenging real life scenarios, including questions related to social media. Feedback |

| 2015 / Kung et al. (12) | Professionalism is the basis of the contract between physician and society (2) | Altruism, duty, responsibility, justice, honour, integrity, respect | Taught through reflexive practice and individual sessions. |

| 2015 / Ning-Zi Sun et al. (13) | Not defined | Care, compassion, presence, competence, commitment, altruism and teamwork | Role modeling |

| 2015 / Hultman and Wagner (14) | The ability and willingness to apply knowledge and skill to a greater societal good. Result of a personal commitment to ethics and conduct. One of the six ACGME competencies. | Integrity, morality and ethics, teamwork, competence, commitment, responsibility, self-control, altruism and autonomy. | Role modeling, readings, journal clubs. Evaluation by direct observation, 360o feedback and portfolios. |

| 2016 / Byszewski et al. (15) | Own definition not mentioned. | Not mentioned | Uses role modeling, hidden curriculum. In the evaluation makes use of LEP (learning environment for professionalism). |

| 2016 / Hochberg et al. (16) | It is a vital component of surgical training. One of the six competencies of the ACGME; involves personal and communication skills. | Self-control, responsibility, teamwork, altruism, communication with the patient and family, respect for diversity and clinical excellence. | Discussion group, videos, role play mini-readings. In the evaluation it uses OSCE to assess the domains. |

| 2016 / Jauregui et al. (17) | Professionalism is dynamic, specific culture. Its definition remains a challenge. There is no consensus. One of the six ACGME competencies. | Clinical excellence, humanism, altruism, duty and service, honour and integrity, responsibility, respect for others. | Role modeling, questionnaire where each domain is evaluated on a ten-point scale - how much has this factor contributed to what I understand by professionalism? |

| 2016 / Coverdill et al. (18) | Acceptability and merit in the care in the passage from the work to the team. | Care, responsibility, confidentiality, adaptability and commitment. | Role modeling |

| 2016 / Riveros et al. (19) | Professionalism is an essential aspect of the doctor-patient relationship and of the quality of health. One of the six ACGME competencies. | Ethical behaviour, managing conflicts of interest, altruism, sense of duty, self-assessment, learning throughout one’s life and accepting criticisms. | Feedback from multiple sources. Does not evaluate all the domains. |

| 2017 / Kelly et al. (20) | The construct includes characteristics of personality, values, attitudes and beliefs or desirable qualities displayed by workers during their activity. One of the six ACGME competencies. | Humanism, honesty, integrity, care, compassion, altruism, empathy, respect for others, duty and service. | Role modeling, iterative group readings, case discussions, hidden curriculum. Evaluated through feedback from multiple sources, OSCE and reflective diary. |

| 2017 / Phillips e Dalgarno (21) | Construct of professionalism encompasses a virtuous, ethical individual who has compassion and practices medicine in a moral and competent manner (22) | Compassion, care, duty, medical expertise, emotional balance and empathy | Role modeling, informal and hidden curriculum; evaluation of clinical case by means of illustrative audio, where the domains are evaluated. |

| 2017 / Cendán et al. (23) | Complex, dynamic and multidimensional construct, involving individual factors, learning and behaviours, sociocultural norms and presents interpersonal and contextual dimensions. | Trustworthiness, responsibility, self-control, adaptability, relations with: school, students, preceptors and patients, other team members, medical principles, commitment to scholarship and advancement in the field | Orientation sessions, mobile platform for professionalism evaluation with positive feedback and feedback from multiple sources. |

| 2017 / Brissette et al. (24) | Relationship between doctor and patient which has undergone changes in recent times with technological advances, the explosion of information, the change in health care provision and with the emergence of more complex fields of practice (25) | Clinical excellence, humanism, altruism, responsibility, duty and service, honour, integrity, respect | Role modeling by staff, health team members from the university, informal and hidden curriculum, sessions and readings. Uses feedback in teaching and in assessment, anonymous online questionnaire for feedback of student attitudes (survey monkey) |

| 2017 / Mitchel et al. (26) | Not defined | Not mentioned | Teaches by means of discussion sessions with daily feedback. Evaluates through feedback on communication skills and professionalism. |

| 2017 / Domen et al. (27) | Professional identity encompasses values and behaviours gradually developed throughout life (28) | Interpersonal relationship, tackling differences and prejudice, confidentiality | Role modeling, workshop with case studies. Evaluation by anonymous online questionnaire (survey monkey) |

RESULTS

The results demonstrate the relevance of this theme to medical education. The concept of professionalism is applied heterogeneously among medical specialities. During residency programs, the construct is approached in the form of domains, which translate behaviours that need to be observed, taught and assessed, by means of multiple tools. Below we present in themes, the results of the research conducted.

Professionalism: multidimensional construct

Most of the articles (11) were published in the years 2016 and 2017. The most commonly cited domains of professionalism were: altruism, responsibility, care, teamwork, self-control, ethical principles and clinical excellence. The domains respect, honesty, honour, integrity, confidentiality and commitment were grouped under ethical principles.

The domains found are partially included in the ACGME, responsible for the certification of medical residency programs, which incorporate in their practices teaching and assessment strategies in ethics and professionalism. According to that Council, the role of the resident physician should include ethics, honesty, contribution to the learning environment, conflict resolution, professional language, full care and protection of patient confidentiality. In his practice, he should also demonstrate: compassion, integrity, response to patient needs in relation to his own interest, respect for diversity, privacy and autonomy, accountability to the patients, to society and to the profession, sensitivity and ability to give individualized responses (3).

In relation to the concepts, eight articles mentioned their own definitions (8,14,16-19,20,23).

The other publications did not define professionalism (9,11,13,15,26) or mentioned other authors’ concepts (10,12,21,24,27), leaving the construct with no consensus among medical specialists.

Teaching of professionalism: role models and the curriculum

Nine articles highlighted the importance of role models represented by preceptors and members of the health team in the medical residency program for the teaching of professionalism (13-15,17,18,20,21,24,27).

The way in which professionalism is taught in specialist medical training affects behaviours in their professional activity after training, generating satisfaction for the program and the society. However, unprofessional behaviours, whether modulated or not, can threaten the patient’s safety (29). The ACGME recommends teaching professionalism through role modeling, case studies on ethics and professionalism, journal clubs, videos and portfolios (3).

According to Cruess and Cruess (30) role modeling constitutes the main strategy for conveying values in the teaching of professionalism. The informal or hidden curriculum, which is learned through experience and observation, also exerts some influence, since it favours the development of a reflective practice in the program (31).

The literature review demonstrated that most the studies develop the teaching of professionalism also through formative feedback, multiple source or 3600feedback, case studies, readings on the theme, workshops, discussion sessions about clinical cases, elements of the hidden and informal curriculum, discussions in small groups, interactive workshops, discussion of clinical cases, videos with cases that give rise to ethical and professional discussion (8- 12,14,16,19,20,21,26,27).The teaching of professionalism through observation of professional or unprofessional behaviours in case studies has been a potential tool in the training of the future professiona (27). Feedback is a frequently used strategy in medical education, contributing to the training of several specialities (10,11,14,19,20,23,24).

Evaluation of professionalism: multiple strategies in the curriculum

In the evaluation of professionalism in medical residency, tools such as written test and online questionnaires (survey monkey) are used (17,24,27). The behavioural evaluation uses strategies in real and simulated environments. There are mentions of direct observation (14) and Objective Structured Clinical Evaluations (OSCE), which assess the domains of professionalism in settings (10,16,20). More than one feedback strategy is also highlighted in the evaluation, such as multiple source feedback and formative feedback (12).

An innovative study in the assessment and remediation of lapses in professionalism involved the development of a mobile platform in accordance with the domains of professionalism, accompanied by immediate feedback (23). Two articles made no mention of the mode of assessing professionalism in the medical residency program (9,13). In the medical residency programs, the adoption of more than one resident assessment and self-assessment strategy is recommended (20).

DISCUSSION

As the results demonstrate, to define medical professionalism is a complex task due to the difficulty in determining the expected conduct of a physician nowadays (32). Determining the domains that compose the medical professionalism construct was aimed at shedding more light on these issues (3). In this regard, two points deserve reflection: the scope of the construct and the cultural adjustments that pervade it (33). The broad scope of the term medical professionalism hinders its comprehensive evaluation, leading studies to work with the domains in an isolated manner (12,16,27).

Although such studies develop the construct in a fragmented fashion, this is not made clear in their justifications, which contributes to the lack of understanding around the theme. Furthermore, the studies do not address regional and cultural nuances capable of interfering in perspectives on professional behaviours, attitudes and values (33). Therefore, studies into medical professionalism and its evaluation need to be more clearly positioned in their educational, regional and cultural contexts (34) in order to afford more transparency to the cultural flexibility required to consolidate a global approach to professionalism (33).

Another key point of the results is the importance of role models in professional training (33). It is worth highlighting here that, despite medical professionalism being a recent construct, there has always been a tacit social rule regarding the expected behaviour of physicians, and the transmission of this standard of attitudes has been consolidated through role modeling, even before it was named as such (32). The importance of teaching medical professionalism in the training of specialists partly derives from the contradictions between the attitudinal training of medical professionals over recent decades and contemporary social demands. The disparity has demanded self-regulation functions of the medical profession, pervading the teaching of professionalism (35). However, the current teachers and preceptors were trained according to the previous model. Hence, the teaching and evaluation of medical professionalism in the training of specialists also require continuing work with the teachers and preceptors. This work requires sensitizing those involved to the importance of constant self-critique and surveillance, at the risk of trainee physicians failing to find in the practice of their models the concepts taught therein (25).

CONCLUSION

Contemporary social demands require attitudinal and relational changes in medical professionals. In this regard, the teaching of medical professionalism as a construct, in the training of specialists can reduce lapses and promote a care guided by respect for people’s autonomy and for social accountability. The teaching and assessment of medical professionalism in the training of specialists, however, are still incipient. The few studies in this area still address the construct in a fragmented manner. Moreover, it is necessary to make the sociocultural position of these studies clearer and to strengthen the work with teachers and preceptors so as to promote positive role modeling.

texto em

texto em