INTRODUCTION

The evaluation of the medical student and the resident physician represents a step of crucial relevance in the educational process, allowing the obtaining of information about learning, as well as the teaching methodology used, which helps in the decision making1.

Among the assessment tools aimed at different competences, direct observation in the workplace has played an important role in these educational reform processes, guiding training programs and improving the quality of teaching2.

The Mini-Clinical Examination Exercise (Mini-CEX) was initially introduced by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) as a practical assessment method for postgraduate physicians3. Subsequently, its use was validated with physicians at all stages of training, in the most varied specialties and clinical contexts: outpatient clinic, hospital or emergency room4.

The method consists in the direct observation of a step of actual care, lasting around 30 minutes, allowing the evaluation of one or more of the following domains: anamnesis, physical examination, counseling, clinical judgment, organization / efficiency and professionalism. It allows a focused analysis, prioritizing the diagnosis and treatment in the context of clinical practice.5 Additionally, a global score can be attributed to the student’s performance impression6.

As the method provides structured feedback after each observation, the Mini-CEX can also be used as a training method to guide the professional development of undergraduate students and preceptors. Previous studies on the Mini-CEX have focused on its validity, reliability and feasibility, not only to assess the residents’ clinical skills but also to study the impact of effective feedback to promote learning and improvement7.

Since it evaluates only a fragment of the provided assistance, it can be repeated in other contexts, with different evaluators, aiming to offer new opportunities for student evaluation and analysis of different domains, in addition to allowing exposure to different points of view of other evaluators through the feedbacks5.

In our country, bedside assessments with interns occur in a non-systematic way, justifying the need for an objective assessment of in-service training of the interns throughout the internship, as well as the training of preceptors in active teaching methodology, promoting greater retention of knowledge by the student body.

Based on this topic, the present study aims to assess the perception of undergraduate students, residents and teachers regarding the Mini-CEX assessment instrument, during an internal medicine rotation at a teaching hospital in Fortaleza, state of Ceará, Brazil.

METHOD

A field research with a qualitative approach was carried out at Hospital Geral Dr. Waldemar de Alcântara (HGWA), located in the city of Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. All appropriately enrolled interns, and professors at Centro Universitário Christus (CUC), and internal medicine residents at HGWA were invited to participate.

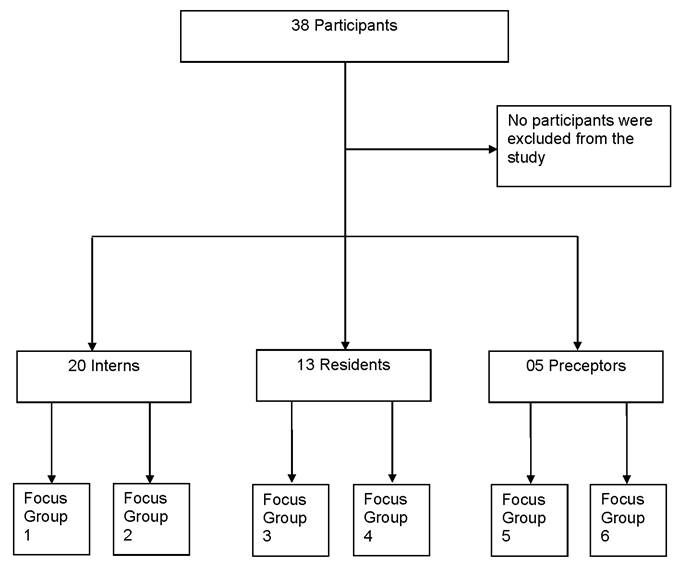

A total of twenty medical interns, thirteen medical residents and five preceptors from the HGWA internal medicine wards (Flowchart 1) participated in the study. This internship consists of a period of thirty consecutive days in the internal medicine wards I, II and III, with a total workload of sixty hours a week for residents and forty hours a week for interns.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário Christus, N. 1,881,091 / 2016. Data collection was carried out between February and July 2017, after the participants signed the Free and Informed Consent form.

The research risks were classified as minimal and the study followed the norms of Resolution 466/12, having as benefits the improvement of the quality of teaching and learning of those involved in the study.

In the first phase of the research, a meeting was held with teachers from the HGWA Internal Medicine (IM) internship to present the instrument and provide training for its application.

As the second step, related to the second and fourth months of the research, the teachers applied the evaluation method to the IM interns. During the third and fifth months, the same instrument was applied to the IM residents, as bedside assessment. Each intern was assessed twice, using the Mini-CEX, during the month of the survey, by the same evaluator. These evaluations were formative, not contributing to the grade attribution for that academic period.

During the months of the research, the interns were also evaluated by the teachers using the conventional, non-systematic method, resulting in a grade ranging from zero to ten.

The focus groups were conducted by M.C.B.M. It consisted of six focus groups: two with interns, two with residents and two with preceptors. Using semi-structured questions, the perception of the methodology used to assess the quality of the evaluation and possible repercussions for the teaching-learning process were evaluated (see flowchart).

From the perspective of extracting the meanings from the actors involved in the study, we used Bardin’s thematic content analysis as a theoretical framework8), (9), (10.

After conducting the interviews and assessing the main contexts, interpretations were carried out, interrelating them with the initially designed theoretical framework, suggested by the reading of the material10.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

After completing the content analysis steps, the categories and subcategories shown in Charts 1, 2 and 3 were built.

When comparing the set of groups, we observed different behaviors in relation to the groups of interns and residents.

Chart 1 Categories and subcategories of Interns

| Category | Subcategory | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback | Strangeness | First time I did it |

| Positive | Main part in the Mini-CEX | |

| Feedback is essential | ||

| On a daily basis, individual feedback is rare | ||

| Negative | It will not change anything | |

| It was not worth it | ||

| Poorly structured | ||

| Bedside evaluation | Positive | I found it quite interesting |

| Because no one had ever done that before | ||

| A valid experience | ||

| Negative | Pressured | |

| I was much tenser | ||

| The evaluator’s subjectivity | ||

| Observation time X Feedback time | Positive | It was quick |

| 15 minutes to be applied | ||

| The application time was adequate | ||

| Suggestions | Evaluation | The evaluator should not stand beside you |

| Evaluation of patients who are not followed by you | ||

| Train with an actor first and then go to the bedside of patient. | ||

| Teaching | Train evaluators to provide more productive feedback. | |

| Good method for medical residency test training |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Chart 2 Categories and subcategories of Residents

| Category | Subcategories | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback | Strangeness | It is strange to have someone evaluating you |

| Positive | Review of some forgotten points | |

| Learning gain | ||

| It was the most worthwhile part | ||

| It was talked about at the strengths and weaknesses | ||

| Negative | It generates anxiety | |

| Bedside evaluation | Positive | It stimulates reasoning |

| It was essential for the student’s and the evaluator’s growth | ||

| Capable to fully evaluate | ||

| Simulates everyday reality | ||

| It was good | ||

| Negative | There was no evaluation pattern | |

| Geared more towards the internists | ||

| It looks like an emergency care approach | ||

| Suggestions | Evaluation | It should assess the history of the current disease |

| Standardize the evaluation time | ||

| Training of evaluators | ||

| Communicate to the patient that a student evaluation will be carried out during assistance | ||

| Teaching | Use longer cases | |

| Use the Mini-CEX more as a teaching process and less as an assessment | ||

| It is good for training for residency tests and applying for civil servant jobs | ||

| Deepen the approach to residents |

Chart 3 Categories and subcategories of Preceptors

| Category | Subcategories | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback | Strangeness | I do not know the application instrument well |

| Positive | What they praised the most was the feedback | |

| Allows the evaluated subjects to see what needs to be improved in their conduct | ||

| Bedside evaluation | Positive | It is an opportunity to see that sometimes you are not giving feedback |

| It was possible to better observe each of the residents | ||

| Negative | When the patient was the intern’s, it was worse because it looked like acting | |

| The perception they had was that they were somehow being judged | ||

| Observation time X Feedback time | Negative | My biggest difficulty was related to time |

| It could not be carried out in 20 minutes, my average was 20 to 40 minutes | ||

| Suggestions | Evaluation | I found them to be more mechanical with their own patients |

| Training of preceptors | ||

| Interview in a more private place | ||

| Predetermined time to apply the Mini-CEX in daily life | ||

| Different instruments for interns and residents |

Regarding the feedback received

In the group of interns, it was reported that it was the first time they had contact with that type of assessment (Mini-CEX), which included a feedback time. The assessed individuals considered in a solid and frequent manner the fact that they did not receive effective feedbacks, suggesting that they were not well structured. This is exemplified in the following excerpts:

Regarding the feedback, I think, well, at least when I did it, I think the feedback was ineffective, because regarding what the evaluator thought that I failed at, he did not correct me, you understand? It was like “you did this, could have done that”, but I think it would be much more valid if the feedback had been “I think the way you addressed the main complaint could have been deeper into that, you could have done it this way [...]”, suggest, teach, and not just put a mark on a paper, how much you get right, how much will be enough [...] (Intern 1).

I did not find it worthwhile. I think it was a “question and answer” thing, which basically was used by the preceptor to assess whether, according to his judgment, I was insufficient, moderate or good, but for me, regarding the return, it was useless! (Intern 2).

On the other hand, we observed that in the group of residents, the feedback was considered valid, since it generated a review of some points that had been forgotten:

I think it is very valid, this question of the feedback, detailing this type of thing that is sometimes very basic, sometimes very obvious, but that we end up overlooking (Resident 4).

Yes, I think the most worthwhile thing was the feedback at the end, the fact that he pointed out “you should have asked this, you should have done that”. I think the feedback was very valid (Resident 3).

According to the preceptors’ speech, the importance given to feedback is also emphasized, leading the student to seek knowledge that he/she had not previously acquired.

The feedback was highly praised, the interns like it, the residents also do, [...] it is an opportunity for you to see that sometimes you are not providing the feedback. [...] That kind of formalizes and standardizes what you should remember (Preceptor 2).

Some of the people to which I applied it, I noticed a search movement, in the sense of “I took the first Mini-CEX and I realized that I failed in this sense, I forgot this aspect and did not do it. I went back to the book and I reviewed it. When I take the second Mini-CEX, I need to correct this”; I found this very interesting [...] (Preceptor 1).

This authors’ understanding is identified in the residents’ interviews, when they refer to the feedback as an instrument that normally results in learning gain and, for this reason, it becomes essential for the students’ growth when they analyze their daily performance.

According to Zeferino et al., learning from feedback requires that the latter be provided in a constructive and positive way, collaborating for the learner to critically reflect on and create an improvement plan in practice. In this sense, the interns reported that they liked the feedback.11 They agree it is the best part of the Mini-CEX instrument, but point out the need for it to be well structured to become effective in learning gain, as seen in the following excerpts, during a reflective proposition about the observed clinical condition or in the improvement guidance, respectively:

I think the best part was the time of the feedback, when he asked: “What would your conduct be? What would your treatment be?”. Because we already know perfectly well how to perform all the data collection [of the anamnesis]. But establishing the conduct, treatment [...] we do not. Because most of the time you have already been handed the conduct, you have received a patient from a resident, or a staff member and you do not think how that conduct could be improved (Intern 6).

The good thing is that they point out: “You have to improve this”. Some faults they pointed out, [...] and over time we get some habits, so it is good to go back, [...] it was very good (Resident 1).

The evaluation feedback [...] is what makes us grow as professionals. We always need that feedback, that is how we find out what our shortcomings are. It is an important assessment. The perception of teaching and learning, I think, I am not really evaluated, actually taking the clinical history, conducting an interview with the patient [...] I am not usually evaluated. So I think it is important to be evaluated at that moment, it helps me to organize my mind and that brings a lot to me. So as I said, it is important for me to evaluate myself as well as for the preceptor to evaluate me (Resident 11).

Giving feedback, according to Zeferino et al., requires skill, understanding the process, creation of a favorable environment and a relationship of trust. It is not possible to inform the students that their diagnostic hypothesis was wrong or that they did not collect all the necessary data during the clinical history without causing a sense of disappointment or frustration. On the other hand, this information is essential and cannot be omitted11.

Bohnacker-Bruce carried out an interesting study from the point of view of the students’ satisfaction and engagement, with feedback. They conclude that the assessed students directly relate to individual feedback, although a minority of them has this opportunity12.

The interns’ interviews support this assertion, as they consider feedback to be an important learning tool and, above all, they reinforce the importance of providing it in an effectively manner:

I think it does not make any sense to undergo a Mini-CEX like this and not have feedback. And then, what? What did I miss? For me, as a student, it is the main part to assess what I did wrong, what I should study about the case, about a conduct [...] (Intern 8).

The feedback was the best part. It literally gives you back things that were perceived in you that are positive and things that you should add at another time. This tends to improve longitudinally (Resident 9).

Feedback is important, even for the personal growth of the person being evaluated, what must be improved, what their failures and their qualities are (Resident 2).

Watling et al. clarify that medical students like both positive and negative feedbacks. However, in the negative comments, they emphasize the importance of these being accompanied by an action plan for improvement13.

As suggested by Sargeant et al., the main quality for the student to receive feedback is the capacity to reflect on the self-assessment and self-perception of their performance and develop internal feedback. This condition, for the authors, will facilitate the acceptance of external feedback14.

About the condition to receive feedback, Borges et al. add that, when only the negative points of the student’s performance are highlighted, a hostile environment is created and, normally, the teacher’s superiority is emphasized, without opening the opportunity for dialogue and then, the teacher’s inhibiting influence is reinforced over the student15. Feedback, according to the authors, requires interaction between both of them and has as a fundamental point the dialogue without preconceptions, always present in the teaching-learning process.

Strong evidence, identified in the literature and the statements in the interviews, suggest that the quality of feedback has an impact on the students’ learning, perhaps more than any other aspect of the teaching process. Therefore, we perceived that best practices associated with giving and receiving feedback are necessary, just as our interviewees also suggested alternative behaviors.

The quality of the offered feedback, as seen in the interviewees’ speech, significantly interfered with the receptivity and acceptance of the message:

So he gave me feedback, I do not feel like he added at all to my training, you know? But, maybe, if I had taken on a more complicated case, if I had had a little more difficulty, you understand? I think it would have helped (Intern 10).

The way it was applied, I think it was not so relevant, I think it would have to be changed a little [...] (Resident 10).

This improvement of those who apply feedback should be reassessed, [...] which is always a moment that I also find difficult, as sometimes it has to be adapted to the student’s personality or the way that he/she sees the feedback, and sometimes you have to perceive how the reaction is in the first few minutes of the conversation (Preceptor 3).

In another study by Watling et al., the study participants highlighted a higher frequency of vague and non-specific feedback in Medicine, in any learning context, and that feedbacks with such characteristics are depreciated by those who receive them. They suggested that, regarding Medicine, it would be interesting to stipulate challenging tasks with clear goals and subsequent aligned feedbacks13.

Borges et al., emphasize that in relation to frequency, good practices regarding formative assessment, they recommend that feedback be offered regularly, in order to offer opportunities for students to reflect and review their practices even during the educational experience and that in addition to being frequent, it must have quality15.

The need for more frequent feedback was also raised and the moment when it was provided during the internship was also questioned:

Because we spend a whole month there, with the preceptors, and we only receive feedback at the end of the month. So, this is the possibility of having another feedback during this interaction. But in practice, I think that our reasoning becomes a little faster [at the end of the internship] (Resident 6).

The evaluation feedback [...] is what makes us grow as a professional. We always need that feedback, that is how we find out what our flaws are. It is an important evaluation. The perception of teaching and learning, I think, I am not really evaluated, taking a clinical history, conducting an interview with the patient [...] I am not usually evaluated. So I think it is important to be evaluated at that moment, it helps me organize my mind and that brings a lot to me. So as I said, it is important for me to evaluate myself, as well as for the preceptor to evaluate me (Resident 11).

The interviews show us that the students recognize the feedbacks as a tool that allows the improvement and the performance of their conducts, when performing the physical examination and in the clinical skills in general, because as much as possible, when their weaknesses are identified, it contributes to the possibility of alternatives for overcoming them.

Bedside evaluation

Regarding this category, interns and residents reported that they had no experience of bedside evaluation with the preceptor. This evaluation did not happen, frequently due to time.

We had never done this before (Intern 5).

Listening while we talked to the patient, no. We collected the patient history separately and then went over it, but not at the same time (Intern 1).

It was the first time I did something like that at the internship. We had something similar at the basic health unit (Intern 11).

I liked it. I also had no contact with this methodology, [...] because we do not have this type of evaluation in medical school. It is strange to have someone evaluating you (Resident 2).

They are there with you as a partner. We will collect the history together with the patient, because on a daily basis you cannot do that with all patients (Preceptor 4).

Some interns and residents comment that they felt pressured by the presence of the preceptor at the bedside, resulting in a feeling of anxiety that led them to behave differently from the usual way in their daily practice.

Normally, before talking to the patient, I wash my hands. But, knowing that you are being evaluated, and that if you do not wash your hands you will lose points, you end up forgetting it, because it brings you the feeling of the anxiety of the test itself. So I think it is not beneficial for the student [to have] the preceptor at the student’s side during the [...] [collection of] anamnesis (Intern 5).

Because at the time I was much more tense, I forgot what I was going to ask. Sometimes I asked and did not grasp the answer. So, for me, it was really bad this issue of him being there beside me at the time (Intern 2).

Of course, during an evaluation, [...] the person being evaluated feels, like it or not, that “stress”, right? Because it generates all the expectations, anxiety [...]. And the preceptor, when he/she is evaluating, has to realize this fact: whether the person is comfortable or not with the practice. [...] (Resident 9).

I confess that I find it a little strange. I do not know if that is because during my formation I never went through this, but I always think it is a “fake” thing, you know? So I think that, right at the beginning, the patient himself gets a little tense. I went through some situations when he was [...]. The intern tried to do the anamnesis and the patient, several times, started speaking to the intern and turned to me to continue talking, exactly when he was having difficulty getting the patient to “focus”. The intern gets nervous. Even though he knows he will not be graded, he gets tense (Preceptor 1).

The bedside assessment allows the direct observation and the possibility of immediate feedback, adding positive value to the student’s training, since they include the three basic requirements of the assessment: 1. The program content, according to the expected skills, aligned with the practice; 2. Offering feedback to the student during or shortly after the assessment; 3. Using the evaluation as a guide to achieve the desired results16.

I think this issue of taking it to the bedside is very valid. Because, sometimes, even our anamnesis, our physical examination [...] is approached in a way that [...] it complements something. Sometimes we get very used to our ‘habits’, don’t we? (Resident 5).

CONCLUSION

According to the data analyzed in this study, it can be said that for the group of interns, the moment of feedback during the evaluation process was considered to be essential, especially because it is rarely performed individually in everyday life. However, they considered it was not well structured and, therefore, it was less beneficial. Regarding the bedside assessment, they reported it was an interesting and unprecedented experience, despite the fact that some of them reported discomfort and tension when being evaluated in the preceptor’s presence. They highlighted the short time for the instrument to be applied as a positive feature and suggested better training for preceptors for more structured and effective feedback.

The residents agreed with the interns regarding the importance of the feedback moment, allowing them to review forgotten topics and indicating points for improvement. As for the bedside assessment, they emphasized the encouragement to clinical reasoning in the presence of a practical situation, although this moment was not standardized for all residents. Suggesting better training for preceptors to apply the instrument was a common point. They also suggested the standardization of the evaluation time and the use of longer and more complex cases, specific to residents, with a greater focus on the teaching-learning process and not on the evaluation.

In the group of preceptors, the bedside assessment was emphasized as an opportunity for a better analysis of individualities. As for the feedback, a positive perception for those evaluated was ratified as a valuable learning tool, although it was not considered to be a simple one, since it has to be adapted to each student. One difficulty was identified in relation to compliance with the time stipulated for the instrument application, mainly by those who had no previous experience with it and, therefore, better training was suggested. The preceptors also understood that greater positive perceptions would come from the application of different instruments to the different groups.

texto em

texto em