INTRODUCTION

Assessment has always been a challenge. According to Sousa and Heinisch1, an ideal evaluation method must have validity and reliability and contribute for the students to further develop their competences, being able to present school performance in the cognitive, psychomotor and affective dimensions1. According to Borges et al.2, the action of assessing involves multiple interpretative tools, such as judgments and comparisons, which makes the assessment mechanism a complex one.

In the scenario of medical education, the use of summative assessment as the only valid evaluation method has lasted for a long time. According to Gomes and Rego3, the basis was a traditional curriculum that did not adequately stimulated the development of autonomy, the capacity for analysis, judgment and assessment, as well as critical, investigative and creative reasoning. As a result, in Latin America, from the 1970s onwards, the debate on medical training intensified. In these debates, both the curricular structures and the teaching process started to be problematized, seeking to improve the level of learning and provide a resolutive method. Then came the advent of the active learning methodology, in which the teacher, in addition to having the teaching function, also assumes the role of facilitating the acquisition of knowledge by the student.

The National Curricular Guidelines for the Undergraduate Medical Course4 state that this course must have a pedagogical project centered on the student as a subject of learning and the teacher as a facilitator and mediator, seeking comprehensive and adequate training. From this perspective, sporadic and classificatory assessments that seek only to compare the student with their peers by demanding they reach a pre-established score, have been losing space in the student environment. On the other hand, models that focus more on the trajectory taken by the student to attain a certain skill and knowledge, and that seek to detect in a timely manner the potential difficulties faced by them and help them to overcome such difficulties, are the templates for the current medical education.

Therefore, based on the understanding of the need for a procedural assessment with monitoring, diagnosis and interventions throughout the educational process4, the formative assessment emerges. It is characterized by being continuous and promoting the interaction between students and teachers. Moreover, it allows correcting deficiencies and reinforces student learning, as well as stimulates reflection and self-assessment skills. This is made possible through the practice of critical and constructive comments, called feedback.

This tool, very important for the learning process to be effective, refers to the information that will be given to the students to describe and assess their performance in a given activity. For that to occur, the observed result is compared with the expected result, which must be based on pre-established competence premises for that determined degree of training2. Thus, it acts as a main instrument to guide objectives and allow the correction of errors at the end of each task2.

At the Universidade Anhanguera Uniderp medical course, of all the scenarios in which the student is assessed, the Interinstitutional Program of Teaching-Service-Community Interaction (PINESC, Programa Interinstitucional de Interação Ensino-Serviço-Comunidade), which is developed in partnership with the Municipal Health Secretariat (SESAU) of Campo Grande, is the scenario in which this evaluation tool is most often used. The PINESC is a practical-theoretical module and its purpose is to train doctors who are able to learn and understand the social, economic and cultural context of the population and the community and their interaction with the biological aspects involved in health and in the process of illness5.

According to Lima et al.5, the students’ evaluation in this module occurs through the association of cognitive and formative assessment. Regarding the formative assessment, it is obtained through the arithmetic mean of the grades at the assessments carried out weekly by the preceptor (reported in the specific assessment form). According to Ryan-Nicholls6, the term ‘preceptor’ is used to designate the teacher who instructs a small group of students, with emphasis on clinical practice and the development of skills for such practice. Through this average, the performance in the activities related to the Attitude, Skill and Cognition items is assessed and, through their combination, a score is assigned (numerical value).

Therefore, according to these brief considerations, the present work intends to discuss the formative assessment in the context of the Interinstitutional Program of Teaching, Service and Community Interaction (PINESC) of the undergraduate medical course at Universidade Anhanguera-Uniderp, emphasizing the role of feedback and students’ considerations about it.

METHOD

This is a quantitative, sectional study, including undergraduate medical students from the first to the eighth semesters (except for the seventh, due to the semester enrollment of classes in the college) attending the PINESC longitudinal module, over 18 years of age and who are regularly enrolled in the medical course at Universidade Anhanguera-Uniderp, in the municipality of Campo Grande, state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

The data collection instrument consisted of a questionnaire for students, with questions about formative assessment and feedback, created after the modification of Marcos and Andrade questionnaire7, and applied on 11/24/2018 at Universidade Anhanguera-Uniderp after approval by the Research Ethics Committee under CAAE number 92606218.8.0000.5161, according to the National Health Council’s (CNS, Conselho Nacional de Saúde) Resolution n. 466/12. The questionnaire consisted of 21 questions, divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 consisted in characterizing the students and considered the students’ semester in progress, the number of students per group of Pinesc and the number of times the preceptor/FBHU was changed as the analyzed variables. In the second phase of the questionnaire, the questions were about the formative assessment, and the analyzed variables were: the existence of the student’s feedback regarding the preceptor, the concept of feedback, whether this was performed or not by the preceptor and, if performed, what the characteristics of this feedback were (periodicity, whether it was done individually or in group, indications of positive and/or negative points, coherence with the academic performance).

The number of students was defined through a probabilistic sample based on parameters specified by Fonseca and Martins8 for a finite population with nominal or ordinal variables. After the calculation, a sample of 216 students was defined, and a simple percentage calculation was performed to define the number of questionnaires for each semester of the course.

After collection, the obtained data were placed in an Excel spreadsheet. Subsequently, the data were imported, and the analysis was carried out using the EPI-Info™ program. A descriptive statistical analysis was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In the context of medical education, Gomes and Rego3 believes that active teaching-learning methodologies - which are based on the use of formative assessment, which includes the feedback - allows an articulation between the university, the service and the community, as they create possibilities for interpretation and a rapid intervention over reality.

Prior to the performed analyses, one of the hypotheses raised in this study was that there was a deficit in the feedback performance within the PINESC scope. If the hypothesis were proven, the result would characterize a huge deficiency in the students’ assessment. After the assessment carried out by the preceptor at PINESC, all the information produced through the interaction of teachers and students to assess the degree of learning is explained in a round of discussions. Through the feedback provided by the preceptor, students are encouraged to reflect and express their opinions about the day’s activities and the assessment received.

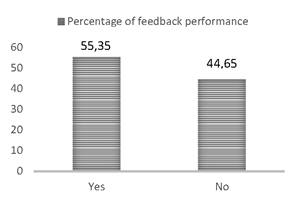

In spite of what was assumed in the hypothesis, 55.35% (Chart 1) of the interviewed students stated that the feedback was performed, contrary to the main conjecture. However, a discrepancy was observed between the current semesters by the students regarding this information, considering that in the initial semesters there was a predominance of this method of assessment, in which 95% (Chart 2) of the respondents in the second semester confirmed that feedback was performed. In contrast, in the fifth semester, 100% (Chart 2) reported that feedback was not performed. This lack of conformity between the semesters can be related to what Poulos and Mahony9) state, who believe that the impact of feedback also depended on the stage of the assessed individual’s university career. Those at higher stages (final semesters) believed that the significance of feedback was not only related to providing information on how to improve grades and performance, but also to what could be used in their professional practice after graduation.

Nevertheless, one should not only perform feedback so that the assessment and learning are indeed beneficial and in line with the student’s performance. There are important characteristics that must constitute this tool to achieve effectiveness. An important characteristic of this type of assessment is that feedback should be used as a tool for constant and continuous feedback, and not only at a privileged moment10. For this self-assessment to be possible, a certain regularity in the performance is recommended. For Borges2, good practices regarding the formative assessment recommend that feedback be performed regularly, aiming to offer opportunities for students to reflect and review their practices while undergoing the educational experience. Pereira and Flores11 also discuss this characteristic, stating that if feedback occurs long after the developed activity, the sense of helping to improve the student’s performance is lost, as it will not be relevant within the learning context of that assessment, activity or process. Nevertheless, in this study, 54.62% of the respondents stated that it was performed only at the end of the semester.

Another aspect is that 87.39% of the interviewed students stated that feedbacks were not carried out individually, so that all members of the group were present. For Borges et al.2, feedback should be given in a context that is not embarrassing, aiming to provide understanding and solve possible doubts regarding the points listed and the performed feedback. Moreover, the environment should be as welcoming as possible, so that the student feels encouraged to question and propose improvements. Therefore, individual feedback would be the best feedback tool, in which the evaluator and the evaluated individual can establish a bond of trust and respect.

In addition to the need to be offered regularly and individually, Zeferino et al.12 postulates that the effectiveness is greater when the feedback is assertive, respectful, descriptive, opportune and specific. That is, the communication between the evaluator and the evaluated individual needs to be clear, objective and direct, assessing the impacts and consequences of this process and proposing improvements and changes. Teacher and student must also be in agreement during the entire process, during which there must be no personal judgments. Furthermore, it is important that the preceptor clarify the reported observations and clearly specifies the positive and negative points. Regarding the content, as analyzed, 81.36% of the respondents affirm that positive and negative points are included in the feedback. Associated to that, 70.59% of the students also said that this assessment tool was applied in a clear and objective manner by the evaluators.

However, despite understanding the content transmitted in the assessment, 49.30% of the respondents stated that only sometimes the feedback is consistent with their performance; moreover, 15.96% stated that they never or almost never consider the assessment to be coherent. According to the definition by Bloom, Hastings and Madaus13, the formative assessment aims to inform the location of deficiencies in the teaching organization to allow their correction and recovery. If there is no coherence in this feedback, one can infer that the deficiencies are not well determined and, therefore, their correction does not occur in an ideal manner. For Oliveira14, only good-quality, timely and guiding assessments are legitimate helpers in the construction of knowledge in a broad aspect, not only of the content itself but also of postures and attitudes. Another point that must be addressed is that, among the students who answered never or almost never regarding the analysis of the evaluation’s conformity, 91.18% stated that they do not expose their opinion about the inconsistency of the assessment to the teacher evaluating them. This reverse feedback, which goes from the student to the evaluator, informs the teachers about the real effects of their feedback, allowing them to regulate how their action will go on based on that assessment. When that does not occur, the errors made by the evaluator persist, leading to a deficiency in one of the assessment functions. For Savaris15, this function is to clarify and assist in the path of learning using concepts such as: correcting, pondering, guiding and establishing goals for the undergraduates’ studies.

In a study carried out by Pereira and Flores11, in which the main objective was to know the perspectives of university students on higher education assessment, particularly on the utilized methods and the feedback, the results showed that participants consider feedback to be an important element for their learning and they appreciate the information transmitted by the preceptors when their learning depends on such information. In this study, according to the concepts of 34.91% of the students, only sometimes does feedback contribute to the improvement of their skills and student training. On the other hand, those who believe that it always contributes comprise 19.81% of them.

The results demonstrate that the perceptions of the assessed students are, in general, positive. However, it is evident that there are several deficiencies in the way feedback is provided, and this can hinder the development of critical thinking and make it impossible to improve academic performance. For Daros and Prado16, the students’ interest in participating in these phases is essential; otherwise, the entire foundation of feedback will be meaningless, making the formative assessment process similar to the cognitive assessment system, thus eliminating its main objective, which is to see the students in their entirety.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study demonstrate that the assessment methods used by the preceptors are extremely important and can influence the learning process in a negative or positive way. The greatest weaknesses identified in this study are related to the way feedback is applied, especially regarding the time between the end of the academic activity and the feedback transmitted by the teacher. Moreover, there is a deficiency regarding the feedback coherence, its collective application and the inverse feedback, which is given by the evaluated student to the evaluator.

It is necessary to emphasize that there is no single way to transmit a feedback, but there are several methods and/or models that can be considered acceptable. Therefore, after some analyses, it is possible to consider that an effective feedback model is the one that has the following attributes: being clear, objective and consistent; being carried out individually, constantly and continuously; highlighting the student’s positive points and point out his deficiencies. Also, allowing the student to reflect on the received assessment, as well as being able to return the feedback to the evaluator on the result of the action when it does not seem to be a fair one. Furthermore, the evaluator must always be attentive to feedback so that it makes the students more motivated and they understand their real performance.

Finally, it is necessary to remember that the provided feedback really needs to instigate a change in what is incorrect and the follow-up of good practices in order to achieve a better result in academic performance and a better teaching-service-community relationship.

text in

text in