INTRODUCTION

The concept of health has undergone several changes over time. Since the Alma-Ata Conference in 19781, health is no longer considered as only the absence of disease, as determined by the biomedical model, but has been expanded to include a holistic view of the individual, while considering its social and psychological context.

Following the global trend, the National Curricular Guidelines (NCG) - responsible for the principles, foundations and purposes of higher education courses - have undergone significant changes since 2001, with important additions in 2014 for the medical course: a differentiated focus has been established in the teaching-learning process, aiming at the integral training of the professional, with work based on interdisciplinarity using active methodologies. Graduates must be able to reflect on their own practice and consider the plurality of human beings in their diagnoses, with a critical, reflective, humanistic and ethical posture2.

The reality worked on by the medical student is a complex one, requiring comprehensive, multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary thinking3. The teaching methodologies, defined by the traditional and active models, encompass different teaching and learning concepts. The first is a methodology centered on a knowledge holder, whose role is passing on the content and it is up to the student to assimilate what has been taught, without asking questions or reflecting on the subject. The second, on the other hand, gives the student the conditions to develop technical, cognitive and attitudinal skills to care for the patient without a hierarchical establishment between the knowledges, but rather the coordinated work for a purpose, that is, having their actions planned together4),(5.

Following the logic of the aforementioned concepts, interprofessionality appears as a complement to multiprofessionality, since through it, one learns in a shared and participatory way with the different realities of the professions, mainly in the health area, developing articulated actions to carry out activities and improve the health care team’s work6.

In this sense, interdisciplinarity is an answer to the need for overcoming the fragmented view of the study object imposed by the curricula used in most universities7. It allows the strengthening of the understanding of the relationship between theory and practice, the rupture with discipline limitations, and the construction of knowledge by the subject based on the relationship with their reality and culture8.

Active methodologies, in addition to providing this union between the knowledges, mainly give the students the capacity to self-manage and self-regulate their training process. This autonomy is fostered by active teaching, such as Problem-Based Learning and Problematization, which aim to raise, through the use of actual problems and interdisciplinary tools - films, short stories, documentaries - doubts, instabilities and intellectual disturbances with a strong motivation to the cognitive stimulus of evoking necessary reflections in the search for creative solutions5.

For the development of this autonomy and the creation of competence that will last throughout one’s professional life, the teacher’s guiding role is paramount. They must have the creativity and willingness to respect, listen with empathy and provide freedom in learning. Going through these experiences with the teacher has the role of providing the student with the capacity to develop performances, aiming to establish intersubjective relationships and maintain them9.

The study of Medicine, despite having human relations in its essence, leads many students, during undergraduate school, to prioritize the biological aspect, making medical practice a mechanistic and not empathetic one10. In contrast to this, the new NCG bring the teaching of the humanities, including literature, as a way to overcome this obstacle.

According to the concept presented by Rede Humaniza SUS11, empathy is the inclination to feel what one would feel if they were in the situation experienced by another person. Very often, the learning environment shows exclusively the application of technological resources, where individuality, competitiveness and pragmatism predominate12. Therefore, there is a minimization of the time during which the student comes into contact with the other, deteriorating the affective bonds that would be established13.

Aiming to rupture with this process, it is necessary to mobilize affection, using non-traditional disciplines in the medical curriculum, such as the Arts and Humanities, including literature, cinema, theater, and painting. This provides students with a better understanding of their patients’ life experiences; the opportunity for self-knowledge; expands their capacity for compassion; allows them to fully recognize the human being, in the health-disease process; to discuss about the moral, ethical and legal dimensions; and to reflect on other aspects of reality14. All the above mentioned models have potentialities to be explored, aiming to achieve these objectives in the students’ education; however, this study gave preference to literature, due to the authors’ previous contact with a teacher who used this tool as a teaching methodology during undergraduate activities.

The teaching of language and, in turn, of literature, is not accomplished only through the transmission of knowledge or a historical aspect that characterized an era but can be used as a formative tool in the education of humankind through the questioning, perplexity and concern about issues addressed by their authors, with the mission of “civilizing” humankind in a way that will make them more reflective and more concerned with their fellow human being, which is both needed and demanded in this area15.

Language is an important communication tool for health professionals. Through professional practice, it is necessary to use it to investigate the patient’s history and health status, thus praising the power of the word. Knowing the linguistic codes, studying them and understanding their regional and cultural variants, will guarantee that the future professionals will have a greater capacity to express themselves and communicate, helping them to situate themselves in the world and, consequently, establishing a greater bond with their patients15.

Literature, as a persistent and immaterial form of human expression15, can be the object of the analysis of a specific culture, period and worldview, resulting in changes in individuals regarding their attitudes and conceptions about pre-existing social values10. In this sense, the question for this research was:

How can literature influence the training of medical students, based on their contact with it, mediated by a teacher, during undergraduate school?

It was assumed that, through the literature, it is possible to expand critical, reflective and humanistic training, culminating in a new vision of the health-disease process, capable of mobilizing professional empathy towards the patient and their disease, facilitating their expression and self-knowledge.

Therefore, this study aimed to understand the experiences of medical students from Faculdade de Medicina de Marília, who had contact with literary texts in the first two years of undergraduate school, at the mentioned school unit using the aforementioned methodology, creating a representative model of the experience.

METHOD

The qualitative research can be defined as a study that considers the essence of social relations and human creativity, both subjective and rational16.

Qualitative investigations can be related to research on people’s lives, their life experiences, behaviors, emotions and feelings, as well as the research on organizational function, social movements, cultural phenomena and interactions between nations17.

This research was guided by the methodological framework of Grounded Theory (GT), which aims to understand reality from the perception or meaning that a certain context or object has for the person, generating knowledge, increasing the understanding and providing a significant guide for the action17. The choice of the theoretical and methodological framework is interconnected in the potentiality of the understanding of the experience.

The GT is not based on existing theories but is based on data from the social scenario itself, thus being a substantive theory, without the intention of refuting or proving the product of its findings, but rather adding other perspectives to elucidate the investigated object18.

This method is structured in the following steps, as proposed by Strauss and Corbin19:

Microanalysis: detailed, line-by-line analysis, necessary to generate initial categories, with their properties and dimensions, suggesting relationships between them and a combination of open and axial coding;

Open coding: analytical process, through which the concepts are identified, as well as the discovery of their properties and dimensions based on the data. Concept is the abstract representation of an event, object or action/interaction that an investigator identifies as being significant in the data and which, in turn, represent phenomena;

Axial coding: it is the process of developing and associating categories to their subcategories, around the axis of a category, that is, linking categories, according to their properties and dimensions, to build the theory;

Selective coding: corresponds to the process of integration and improvement of the theory, in which the categories are organized around a central concept of motives (central category), which encompasses the main categories that are related to it, through explanatory notes of the relations (memos), associated to other techniques, such as the use of diagrams to facilitate the integration process.

In order to intimately understand the experience of the participating actors, semi-structured interviews were conducted based on the guiding question “How was your experience with literary texts at the beginning of your medical training?”; however, with the flexibility of asking the interviewee to clarify or develop important points for the understanding of the investigated phenomenon.

The interview was initiated with the guiding question, in a general and comprehensive way, in order to give the interviewees the freedom to comment on their experience with the methodology used by the teacher. Through a previous semi-structuring action, some topics of the script were included during the interview, in a natural and simple way, by asking questions and trying to understand whether the experience resulted in attitudinal and competence changes, whether it had an impact on the humanization of care and its practice with the patient. Moreover, aspects of the methodology and didactics used by the teacher were investigated, indicating weaknesses and strengths of this strategy and the recalling of some remarkable text with which the interviewee had contact.

During the interviews, methodological notes (of criticism, suggestions or other notes pertinent to the observer’s conduct) and observation notes (recording of gestures, words, phrases used by the interviewee) were taken whenever necessary, to explore all verbal and non-verbal data that emerged.

Moreover, the interviews were recorded in audio and transcribed in full, during which they went through the open coding process before the next interview was performed, according to the model described in the GT, allowing the content and its consistency to always be evaluated and revised before the next interview. This open coding is performed by trying to extract the interviewee’s speech ideas. It is performed line by line, following the precept of microanalysis, with the objective of later correlating it with other concepts for the theory construction.

Table 1 Example of Interview Transcription and Coding.

| Excerpt from the interview | Code |

|---|---|

| Interviewer 1: Can you see a power in that? Something good, a strength in teaching, in the use of literature in medical education? | - Agreeing that the experience they had with literary texts together with their working group should be worked with other PPU (Professional Practice Unit) groups. (T5.3) |

| T: Yes, ah, I can, but, you know, I think it would be interesting if all the groups had this, this connection, but at the same time that there were people, in our own group, who liked that, there were a lot of people who resisted, who did not care ... There are some people who are a little more introspective, but it is not because the person wants to be introspective, that is the way they are [...] | - Recognizing that there are the peculiarities of each person on being adept to and enjoying the dynamics they had with the literary texts. (T5.3) |

With the formation of these codes as a result of the interview transcriptions, a similarity of ideas, meanings was observed, which allowed following the methodological framework with the grouping of these data, generating subcategories. These subcategories were subsequently grouped into categories, thus resulting in the central category, which encompasses, in a complex way, the entire process and experiences extracted from the interviews with students regarding the methodology. This central category guides the creation of the theoretical model that synthesizes the result obtained from this research.

This study was conducted at Faculdade de Medicina de Marília, with undergraduate medical students. In this scenario, from the creation of the courses until the 1990’s, there was a curricular organization based on traditional teaching methods, with the teaching centered on the development of techniques and focused on the hospital scenario, with emphasis on the knowledge conveyed by the teacher. The start of new educational projects for medical and nursing courses occurred, respectively, from 1997 and 1998.

According to the curriculum of Famema20:

The curricular structure of the undergraduate courses of Famema is an annual one and organized in years with the following units: Professional Practice Unit (PPU), Systematized Educational Unit (SEU) [...]. In the first and second years, these units are the same for the two courses (Medicine and Nursing). [...] (p. 02)

At the PPU, in each activity [...], the health needs of the person/family are problematized, the health problem is formulated, and a care plan is created. These practices are alternated with moments of discussion, with the entire group, in which each pair of students elects one or more situations to be presented. [...] The PPU is developed in the first two years in Family Health Units, focusing on primary care and the health surveillance model. (p. 02)

At the SEU, the stimulus for learning comes from the representation of reality, through a previously created [...] problem. The SEU uses the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) methodology. The activity takes place in small groups, in tutoring sessions, where the problem is used as a stimulus in the search for knowledges (knowledge, values, representations, experiences) and the understanding of concepts. (p. 03)

Literary tales were used during the PPU activities, which are geared towards professional practice, allowing students to get in touch with patients since the first year of undergraduate school. In the first two years, the PPU is carried out in groups with 12 students, 4 from the nursing and 8 from the medical school. This educational strategy was carried out by the teacher responsible for some of these groups, in different classes.

The choice of texts, which were read individually and discussed collectively, came from the teachers themselves, according to the needs identified in the group, without a pre-established periodicity. The stories were used as triggers for a certain discussion, both regarding experiences that had been faced, such as, for instance, the death of a patient and the consequent reflection on mourning, as well as about topics that would be studied or activities that would be carried out later. Additionally, in part of these groups, at specific moments, movies were also used with the same objective.

The interviewees mentioned some of the stories they worked with, such as “Aniuta”, by Russian writer Anton Tchekhov21, which deals with the importance of empathy in the doctor-patient relationship, in addition to issues such as mortification and modesty. This was the trigger for the group to be able to study the physical examination in a more humane way. Other short stories were also remembered, such as “Minha Vida como uma Bolsa” (22 (My Life as a Bag), which used the personification of objects to talk about equality and discrimination, and “Dentro do Bosque”, (Yabu no Naka) from the book “Akutagawa”23, which was addressed before a data collection was carried out in the community where the students would work, to demonstrate that there are different views on the same situation. To address the topics of death and mourning, the short stories “A Vida de Mãe Parker”24 (Life of Ma Parker) and “A Cara Engraçada do Medo” (25 were chosen.

Teachers have a crucial role in this type of educational strategy, because the initiative of being willing to use other ways to instigate the students’ reflection comes from them, so the students can understand subjects that are beyond the books. Through the analysis of human arts, such as literary texts, students are able to have a better understanding and critical sense of situations that they will go through during their academic and professional life, which would not have been dealt with if the teacher, at first, had not introduced something new in the way of teaching9.

As an inclusion criterion in the study, we considered those students who had not finished undergraduate school and who participated in groups coordinated by the teacher who implemented this educational strategy. The research participants were randomly selected, by drawing lots, considering all years of the medical course. Nursing students were not included due to the focus on changes in the DCN to the medical course.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. The instrument used included the following items:

Identification of the interviewee: name, age, year, gender, date of birth and previous graduations.

Guiding question: “How was your experience with literary texts at the beginning of your medical training?”.

Support script: 1. Changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills; 2. Articulation of literary texts with practice scenarios; 3. Influence on their view of humanization and empathy; 4. Fragility, power, change in the educational strategy; 5. Meaning; outstanding text.

All interviews were attended by two authors, responsible for explaining the objective of the study to the participant and conducting the interview based on the guiding question, contemplating the other items in the script. The number of participants was defined by theoretical saturation, in a process that involves concomitant interview and analysis, that is, when no new data appears in the interviews and the concepts are apprehended so that a theoretical model of the experience is constructed19.

Additionally, the theoretical sampling means that, instead of being pre-determined before the beginning of the research, it is developed during the process, being cumulative, adding to the collection and analysis of previous data. That is, the aim of theoretical sampling is to maximize opportunities to compare “incident facts or events to determine how a category varies in terms of its properties and dimensions” (19.

Data collection took place in accordance with the favorable opinion of the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) under n. 2,300,058 and a PIBIC / CNPq grant n. 800498 / 2018-6. All interviewees signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (ICF) to participate in the research.

A pilot interview was conducted to validate the research instrument, consisting of a guiding question and a script that previously contemplated the objective of the study. The theoretical saturation of the study occurred at the 12th interview. All authors participated in the process. The interviews were recorded, transcribed in full and then coded, line-by-line, before contacting the next interviewee. For the presentation of the results, the students were identified as follows: the letters correspond to the initials of the student’s name, the first number is the school year to which the student belongs, and the number after the period represents the page of the transcript.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

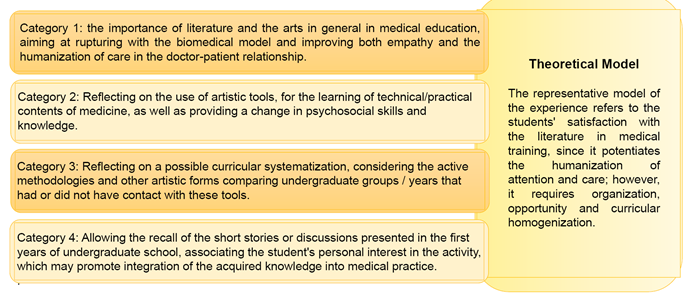

Twelve medical students who had contact with literature in the first two years of undergraduate school participated in the interviews. Four categories were identified, culminating in the model that explains the students’ experience with the literature in the aforementioned medical school.

Category 1: the importance of literature and the arts in general in medical education, aiming at rupturing with the biomedical model and improving both empathy and the humanization of care in the doctor-patient relationship.

This category arose from the interviewees’ report that the short stories proposed a break in the expectation of learning based on the biologicist and traditional model that constitutes the medical courses. Newly enrolled students had the general idea that, to learn this science, consecrated subjects such as Physiology, Anatomy, Pathology, and Semiology would suffice.

Faced with a different methodology, in which students had activities such as reading short stories and discussing them in a group, thinking it was strange was a common feeling among students at first. However, throughout the process of working with this methodology, reading the short stories, which mostly contained questions about human and cultural aspects, brought a greater perception of humanization. Silva, Gallian and Schor20),(21 state that a classic literary work not only has cultural particularities of an era but is also capable of introducing conceptual or moral values that involve yearnings, emotions, feelings and affinities common to human life.

This activity allowed students to learn to see patients in their entirety, in addition to awakening and maturing the concepts of empathy and ‘the other’ in care. In this sense, the artistic representation provides an education of feelings, as this can interfere with the construction of identity, with the representation of life made by art. Based on this understanding, the person becomes responsible for the other 26.

I think you learn to be a little more aware of the ‘other’, to learn how to interpret the person’s life from their side, try to see through their eyes, you know, the context that is happening in life, there, that context of the person’s moment. Not only because of their background as a medical student. (O4.1)

Some students also identified the fact that the literature provided greater authenticity when the student performed the care, learning to communicate and talk to the patient without the rigidity of the “checklists”, that is, the mechanization of the consultation.

That’s it ... Make less use of the checklist. To understand more the patient’s need. Like, we talk, exchange ideas, you know ... To understand why the patient is there in front of you, at that moment. (P6.1)

(...) it made me see that, like, we always have to adapt to the patient (K6.2)

Specifically, the work carried out by reading the short stories reduces the discrepancy between the patient’s experience of the disease and the interpretation that the student/future doctor makes of it, making both understand each other. Literature clarifies aspects not addressed by science, such as the experience that patients and their families have of certain diseases, which contributes to eradicate social stigmas in some of them27.

Consequently, this is reflected in the practice, in which the students realized that by understanding the patient’s context, rescuing human aspects and avoiding the mechanization of the consultation, the patients felt more comfortable, allowing the creation of the essential bond in the doctor-patient relationship.

This corroborates the discussion that the literature can provide reflections on values, human relationships and allows the student to deal with the real patient, developing the ability to interpret experiences and relationships with increased empathy and bonding, in addition to linguistic fluency28.

Category 2: Reflecting on the use of artistic tools, for the learning of technical/practical contents of medicine, as well as providing a change in psychosocial skills and knowledge.

This category sought to contemplate the students’ perception of how the contact with artistic tools contributed to the acquisition of new knowledge, whether technical-practical, emotional or psychosocial.

Many pointed out that literature is a good strategy to introduce necessary topics of medical knowledge in its practical part, such as knowledge of the steps that must be followed to carry out an anamnesis and how to behave when performing the patient’s physical examination. The introduction of such concepts through short stories made the students become familiar with the topic, so that they subsequently started looking for semiology books to consolidate their learning.

Look ... Because the text by Millôr Fernandes brings the idea of why you do the things you do in the anamnesis, why you ask the person about their whole life, why you investigate everything that happened, it was more in the sense of seeing what I am going to investigate. There is even a phrase in which he says, “you only ask what you know and you only investigate based on what you ask”. Then it was, this is it, in that sense of things, you know? (L2. 3)

Therefore, the artistic tools, in addition to addressing the humanistic aspects of health, by promoting empathy, also contribute to the development of other skills useful for learning. The exercise of associating literary texts to clinical practice improves the skills of comprehension and interpretation during medical care. Moreover, other strategies, such as the theater, can be used to encourage teamwork, whereas painting, for instance, can contribute to the study of Anatomy29.

In addition, many students pointed out that the contact with the stories allowed attitudinal changes and an amplified view of the world, promoting the rupture with prejudice, pre-judgments and the lack of knowledge of experiences they never had. According to them, this acquired change is so important that it transcends technique and makes them reflect on such learning even in the subsequent years of training.

So, I think it was very good in that sense, like, showing that there is not only one world, right?, there are many realities that we often have no idea about. So, through the stories, she... We could see these other experiences, these other understandings even by these other people, yeah ... (K6.1)

The use of literature and audiovisual resources, such as cinema, provides reflection on political and social issues, also generating questions about oneself and about the learned values. These tools, which greatly contribute to active teaching methodologies, also promote the development of clinical skills in medical students, such as the skills of observation and interpretation of human experiences. To deal with the dilemmas and the plurality of opinions in the health area, it is essential that students acquire a critical capacity during their education, developing their citizenship and social responsibility28.

However, some speeches were opposed to the complete substitution of the methodological strategy utilized from short stories for the traditional learning, represented through semiology classes and the opening of specific learning questions. They defend the activity as being complementary.

I think it cannot be replaced; the technical part cannot be replaced. The ideal would be to open questions about anamnesis and a correct physical examination and complement it with some readings such as those. (M4.2)

According to Paulo Freire’s thoughts about the ideal educational format, the educational process should not be a mere content deposit, it is necessary that it problematize man’s relations with the world through methodologies that allow true learning, and not just the isolated memorization. of concepts30.

Category 3: Reflecting on a possible curricular systematization, considering the active methodologies and other artistic forms comparing undergraduate groups / years that had or did not have contact with these tools.

It comprehends the importance that students attributed to the experience with the literature and the feasibility of its inclusion in the curriculum together with other active methodologies that were utilized. However, for such implementation to occur, many critically analyzed their experiences and how the activity was structured, about the amount of texts used - there were students who considered that there were few short stories, while others said there were many - and the dynamics in the discussions about the stories.

When analyzing the interviews, there were also many suggestions, which were based on the best time to carry out the activity during undergraduate school, the scenarios in which they would have felt its applicability, the order in which the texts should be read and how the space could be better used, with people’s greater adherence and participation.

But it would be fundamental if, for instance, during the cycles that we have in the fourth year, which is the moment that we discuss, it could be implemented, in the third year ... For me, we could have it every year, because I think the humanized look is not limited to the first and second years. (A4.4)

Ah, in relation to the curriculum itself, it starts since the first year, you will get not only 5 short stories, but you will receive 15 short stories and during the 2 years of the PPU, we can go on reading and illustrating. But it is the teacher who has to provide them, ask critical questions to the students (H2.4)

Despite the worldwide trend to introduce medical humanities, there is still no consensus among students or specialists on the ideal model of approach: optional or mandatory; evaluated or extracurricular. It has been demonstrated that the type of curricular proposal greatly influences the student’s level of acceptance. When comparing the formats of the humanities course at the University of Durham, Balbi, Lins and Menezes28 show that the third-year volunteer student participated and appreciated the content more. On the other hand, when the course was part of the mandatory curriculum of the last year, most students did not find it useful.

In the teaching of humanities, in many medical schools, there are curricular integration weaknesses, use of inadequate teaching methodologies and lack of teacher training in the area. The problems are no longer related to becoming aware of the need for a humanistic approach in medical training, which is already well established, but in relation to the frontiers of a specific knowledge field31.

Therefore, according to the interviews, the implementation of the work with the short stories as a methodological strategy and homogenization performance among the groups would be important for the organization of the activity, favoring its dissemination to more individuals and the possibility of a curriculum design to permit responsibility and participation, while strengthening the humanistic approach to medical training.

Category 4: Allowing the recall of the short stories or discussions presented in the first years of undergraduate school, associating the student’s personal interest in the activity, which may promote integration of the acquired knowledge into medical practice.

The category refers to the factors that led to the adherence and appreciation of the activity, taking into account the student’s personality characteristics and interests, such as the previous habit of reading before the activity and appreciation for literature.

Some short stories had a simpler content and a positive view of the human side of professional care, addressing respect, embracement, empathy, while others proposed greater reflection by opposing the first topic with more consistent ones, with the intention of provoking questions about the practice, aiming at a rupture with the biomedical-technicist model.

So, some short stories brought with them a beautiful relationship between Medicine and society, and others brought a kind of tense relationship, such as, you know, like, very scientific, when you don’t look at the person as a whole, just look at parts, so I think it had both sides, so, at the beginning of the undergraduate school, we see a lot of that, right? We see health needs, we see the SUS theory, etc. So we see this part of humanization a lot. (A4.2)

Most of the interviewees mentioned short stories or excerpts from the short stories that were the most impressive, highlighting the short story ‘Aniuta’ by Russian writer Anton Tchekhov21, in which he portrays the case of a young doctor who used the patient as learning material without caring about the biopsychosocial aspects. This story mainly, as well as others, provided theoretical-practical articulation, allowing students, through reflection, to develop tools in the medical practice of a more humanized care:

Because it led to the conclusion, like, that the person will not always speak ... neither a patient, nor a person will speak the truth, sometimes they will contradict the information and this text kind of illustrated it a lot. If I am in a situation like this in the future, I will reflect on it ... On that text, it talked about it ... It will make me more attentive, so it illustrates better. (H2.3)

It was also discussed how the contact with the stories intensified the interest in reading by those students who already had the habit of doing it and aroused interest in those who did not have them.

It made me more interested in it, this is true, but it was not something like that, because I was not disinterested before, you know? It only increased my interest. (L2.2)

It was also possible to observe that the used methodology allowed the participation of students who had not read the short story, showing the effectiveness of the discussion between the members of the group and, consequently, encouraging further reading and recommendation to other people.

I think it generates discussion within the group itself, so ... Even for those who have not read the text, if I read it, I can discuss it with you, then you say, “oh that’s true” and sometimes you don’t even have to read the text, but when you disseminate this text, this person who reads it will disseminate it to other people around you, isn’t it. (P6.3)

Once the activities rescue the students’ previous knowledge and associate them to the text they read, the participants have an experience of art in which there is not just one interpretation considered correct, since the reading becomes valid based on the students’ perceptions26.

Such experience, being, at the same time, individual and shared, leads to expanded views on values and meanings through contact with different aesthetic perceptions, allowing a humanizing training practice26.

Therefore, the relationship was clarified, that those students who practiced reading had good adherence and use of the activity with the possibility of amplifying the search for more texts and contact with humanization.

Theoretical model

Based on the categories presented above, it was possible to understand a theoretical model that contemplated the objective of understanding the experience of medical students from Famema based on the contact with literature in the first years of undergraduate school.

Thus, a representative model of the experience refers to the students’ satisfaction with the literature in medical education, potentiating the humanization in health care and attention; however, it requires organization, opportunity and curricular homogenization.

The diagram below shows the categories and the theoretical model derived from the experiments:

CONCLUSION

The model comprises the idea that the literature in medical training potentiates the humanization of care and attention and ruptures with the biomedical model, and for this teaching strategy to reach its full potential, it is necessary to have organization, an opportunity for all and curricular homogenization, including student and teacher training.

The study was carried out from the perspective of students who had contact with literary texts in the first years of undergraduate school, so that, for a better understanding of the phenomenon, it is suggested, as a topic for future studies, to consider the viewpoint of students who did not participate in groups that used the analyzed methodology, in addition to the perception of Nursing students who are part of the PPU group and the teachers involved in curricular operationalization.

It is emphasized that the teacher is of utmost importance in this learning model, considering that it is inherent to their role the reflection and the choice to present students with a new way of analyzing, reflecting and experiencing the practice scenarios, while included in the work setting, in affective, supportive and empathic contact in relation to the other.

The potential of the study has its scope in the possibility of presenting it to the community and academic management by proposing strategies to strengthen humanization in the curricular perspective of medical and teacher education.

texto em

texto em