INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, mental disorders are accountable for the segregation of patients in many diverse cultures and historical moments worldwide. The evolution of neuroscience, technologies and advances in the psychosocial sphere have not been enough to change this paradigm. Many people still fear having social relations with someone with a psychiatric disorder, despite scientific progress and efforts to reduce prejudice in recent decades1)-(3.

A psychiatric diagnosis is still associated with several factors - often referred to as stigma - that affect the patients’ quality of life in the community and in therapeutic environments. Health professionals are not immune to stigmas that affect these patients, resulting in a decrease in the search for care by a signification portion of this population and imposing obstacles to treatment, including in other medical areas such as medical clinic and specialties1)-(3. Thus, the experience resulting from having a psychological illness is added to a second dimension of suffering characterized by the social discredit associated with the disorder4),(5.

Health care professionals may have negative attitudes when a psychiatric diagnosis is suspected2),(6, with disastrous consequences for the user of a mental health service, such as delay in requesting help, greater social isolation and reduced possibility of functional return4.

Considering that the improvement of general practitioners’ attitudes towards mental health and psychiatry may depend both on the curriculum and on the development of teaching and learning strategies, research aimed at improving students’ contact with these areas should not be underestimated, as it may indicate possible interventions7)-(9.

The possible relationship between these perceptions and the training of general practitioners encouraged the choice of Internal Medicine residents as the object of study. Thus, this study aimed to analyze feelings, perceptions and stigmas among internal medicine residents when providing care to patients with mental disorders.

METHODS

This is an exploratory, cross-sectional study that used qualitative and quantitative approaches as shown below.

After ethical approval under CAAE 01561518.7.0000.5373, all first- and second-year residents of the Internal Medicine Program of Faculdade de Ciências Médicas e da Saúde da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (FCMS-PUC-SP) were invited to enroll in the study, with 36 possible participants.

For comparison purposes, the quantitative data collection was also applied to eight of 10 Psychiatry Program residents. The quantitative questionnaires used comprised a structured questionnaire to characterize the sociodemographic profile of the participants and the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ-26B), an instrument to measure stigma adapted and validated for the Brazilian Portuguese language10.

AQ-26B comprises 26 questions addressing discomfort felt by the respondent regarding psychiatric patients in daily scenarios. It encompasses eight factors consisting of questions with scales ranging from 1 to 9, in which the higher the grade, the higher the discomfort. The final grade of each factor is the average of grades, i.e., the sum of scores divided by the number of questions in each dimension.

The scopes that comprise the questionnaire and the phrases that translate their meaning are (30) :

Fear: people with mental disorders cause fear because they are unpredictable and violent;

Help: people with mental disorders do not deserve help;

Segregation: people with mental disorders should be sent to institutions outside the community;

Avoidance: I do not want to live with people with mental disorders;

Pity: people with mental disorders are dominated by their disease, deserving concern and pity;

Anger: people with mental disorders are to blame for their disease and make other people angry;

Responsibility: people with mental disorders are able to control their symptoms and are responsible for their disease;

Coercion: people with mental disorders must undergo treatment.

The quantitative data received statistical treatment using IBM SPSS Statistics® software, version 20, used for the analyses and boxplot charts. The results were assessed by group comparison tests to estimate whether there is a difference in perception related to psychiatric patients regarding the responses of Internal Medicine residents to questions on personal and academic history. Internal medicine and psychiatry residents were compared in each dimension of the questionnaire by the Mann-Whitney hypothesis test, with a significance level of 5%. When data was normally distributed, the Student’s t-test was used to compare the two independent tested groups. The description of the population was performed using descriptive statistics with measures of dispersion.

Afterwards, the internal medicine residents who answered the quantitative instruments (n=32) were personally invited to participate in a focus group and 14 of them accepted the invitation. The focus group technique was chosen to attain a deeper qualitative analysis of Internal Medicine residents’ feelings and perceptions about the provision of care to patients with mental disorders. The group met only once and was conducted by an experienced nurse, who acted as moderator, without any connection to the residency program of the institution but linked to the postgraduate program. Every speech in the focus group was recorded during 52 minutes until saturation of ideas occurred and each participant was able to choose their identification based on numbers and code names aiming to preserve their identity. The guiding questions of the focus group were: “How is it for you to provide care to someone with a mental disorder?” e “How do you see the training you received when you provide care to someone with a mental disorder?”.

The study qualitative analysis was converted into categorical analysis based on the content analysis of Laurence Bardin11, with results that stood out from the others as illustrated by Pareto charts.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic data. Table 2 shows that Internal Medicine residents have significantly higher medians than Psychiatry residents in the attribution questionnaire regarding the factors fear and anger, i.e., when compared to Psychiatry residents Internal Medicine ones expressed in their answers that people with mental disorders cause fear due to their unpredictability and aggressiveness, are to blame for their disease and make people around them angry.

Table 1 Categorization of Internal Medicine Residents.

| Gender | N | % | Residency year | N | % | Personal history of mental illness or drug use | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 17 | 53.13% | First | 21 | 65.63 | No | 19 | 59.38 |

| Male | 15 | 46.88% | Second | 11 | 32.38 | Yes | 13 | 40.63 |

| Total | 32 | 100% | Total | 32 | 100 | Total | 32 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | N | % | Medical School attended | N | % | Family history of mental illness or drug use | N | % |

| White | 30 | 93.75% | PUC-SP | 17 | 53.13 | No | 31 | 96.88 |

| Black | 1 | 3.13% | Other | 15 | 46.88 | Yes | 1 | 3.13 |

| Yellow | 1 | 3.13% | Total | 32 | 100 | Total | 32 | 100 |

| Total | 32 | 100% | ||||||

| Religion | N | % | Year of graduation | N | % | |||

| Catholic | 26 | 81.25% | 2017 | 15 | 37.50 | |||

| Evangelical | 4 | 12.50% | 2018 | 7 | 17.50 | |||

| Spiritist | 1 | 3.13% | 2016 | 6 | 15.00 | |||

| None | 1 | 3.13% | 2014-2010 | 12 | 30.00 | |||

| Total | 32 | 100% | Total | 32 | 100 |

PUC-SP: Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo.

Table 2 Comparison between residents by specialty.

| Residency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine (n=32) | Psychiatry (n=8) | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 27.00 | 3.00 | 28.00 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 28.00 | 0.235 |

| Fear | 4.04 | 1.87 | 4.00 | 2.04 | 0.83 | 1.93 | 0.001** |

| Help | 2.48 | 1.07 | 2.38 | 2.03 | 0.71 | 1.88 | 0.273 |

| Segregation | 2.60 | 1.64 | 1.88 | 2.19 | 1.47 | 1.50 | 0.539 |

| Avoidance | 5.20 | 1.66 | 5.33 | 4.67 | 1.93 | 3.83 | 0.438 |

| Pity | 4.55 | 2.53 | 4.75 | 3.31 | 2.27 | 2.50 | 0.197 |

| Anger | 2.37 | 1.56 | 2.00 | 1.31 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.027** |

| Responsibility | 1.53 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 1.31 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.630 |

| Coercion | 6.77 | 1.71 | 7.00 | 7.13 | 1.58 | 7.75 | 0.607 |

*Variables at the Student’s t-test with a significance level of 5% (Help and Avoidance).

**Variables at the Mann-Whitney test with a significance level of 5% (Age, Fear, Segregation, Pity, Anger, Responsibility and Coercion).

Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) and median.

The help, segregation, avoidance, pity, responsibility, and coercion factors showed similar scores between Internal Medicine residents and those in Psychiatry, with a significance level of 5%.

Most Internal Medicine residents declared they had participated in mental health care training during the undergraduate course (62.5%), but only 6.25% reported having had a similar experience during residency. Approximately 75% of residents claimed they had access to patients admitted to the psychiatric ward during their training in a general hospital.

In Table 3, it is noteworthy that differences between the years in internal medicine residency showed a significance level of 5% for the anger factor. Thus, it is estimated that first-year residents perceive patients as being to blame for their disease and responsible for causing anger in other people more than second-year ones.

The remaining factors and age showed similar results regardless of the residency year, i.e., they had a p-value > 0.05 in the tests. The highest mean values are related to coercion and avoidance, respectively the obligation to follow the treatment regardless of one’s will and the lack of desire to live with patients that have mental disorders (Table 3). This conclusion is possible because, in a scale from 1 to 9, the means are considered high when they exceeded 4 among these factors.

Table 3 Tests of descriptive variables in Internal Medicine Residents.

| Residency year - Internal Medicine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (n=21) | Second (n=11) | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 27.00 | 3.00 | 26.00 | 29.00 | 2.00 | 28.00 | 0.067 |

| Fear | 4.00 | 1.84 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 1.86 | 3.14 | 0.186 |

| Help | 2.00 | 0.98 | 2.25 | 3.00 | 1.14 | 3.00 | 0.081 |

| Segregation | 3.00 | 1.74 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 1.38 | 1.75 | 0.238 |

| Avoidance | 6.00 | 1.61 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 1.67 | 5.00 | 0.148 |

| Pity | 5.00 | 2.65 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 2.38 | 5.00 | 0.845 |

| Anger | 3.00 | 1.61 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.27 | 1.00 | 0.042* |

| Responsibility | 2.00 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.667 |

| Coercion | 7.00 | 1.47 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 2.12 | 7.00 | 0.667 |

*Variables at the Student’s t-test with a significance level of 5% (Help and Avoidance).

**Variables at the Mann-Whitney test with a significance level of 5% (Age, Fear, Segregation, Pity, Anger, Responsibility and Coercion).

Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) and median.

Focus Group

While treating and interpreting the results, the exclusive categories created to decode both questions, after a critical, thoughtful analysis, aiming to unveil what “was not said” were:

Negative feelings: whether the residents talk about their fear of treating psychiatric patients;

Gaps in training during undergraduate medical school: whether the undergraduate course provided or not appropriate training for the residents to feel safe while providing care to patients with mental disorders;

Care responsibility: when the residents feel that a psychiatric patient is not their responsibility, but the psychiatrist’s;

Legitimation of complaint: when the residents are skeptical of complaints made by a patient with mental disorders.

For instance, if the respondent reveals that they were afraid to provide care to a patient with a mental disorder, the fragment is placed in the category “Negative feelings”.

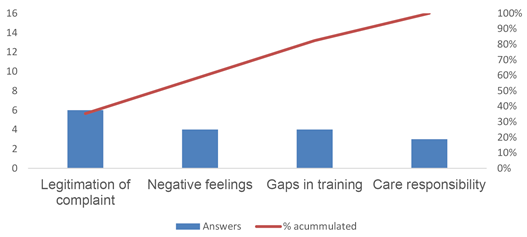

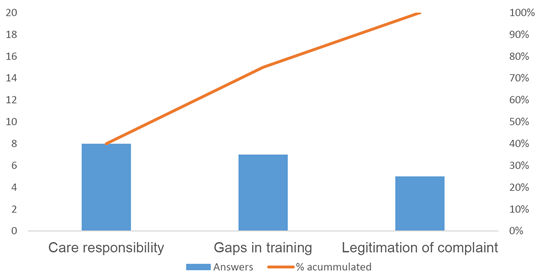

The speech fragments were individually categorized because the focus group seeks to obtain spontaneous answers and each participation corresponds to a different individual who is expressing their experiences. The number of answers that fit each answer category about medical care and training to provide care to psychiatric patients was demonstrated through Pareto charts, where it is possible to verify which category prevails in each question, allowing the researcher to make more objective inferences about what the internal medicine residents’ greatest discomfort is when providing care to psychiatric patients.

“How is it for you to provide care to someone with a mental disorder?”

The categorization of answers given in the focus group, exhibited through Pareto charts, showed that the legitimation of complaint is the biggest difficulty identified by residents during psychiatric care (Chart 1).

This means that most participants reported doubting the accuracy of complaints by patients with mental disorders during the medical care. Those categories with accumulated percentage of less than 50% are considered the main ones appearing in the focus group. Therefore, although relevant, negative feelings, gaps in formation and care responsibility are reasons for less concern when designing action plans.

“How do you see the training you received when you provide care to someone with a mental disorder?” About the training received by the residents to provide care to patients, the category that prevailed was care responsibility (Pareto Chart 2).

Residents felt that, as mental disorders are considered complex conditions, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, the professional actually responsible for treatment would be a psychiatrist. They claimed that, when providing care, interdisciplinarity should be prioritized with at least one psychologist per Basic Health Unit. Gaps in training and the legitimation of complaint appeared as secondary reasons, associated with the training the residents had in in medical school. The category negative feelings did not appear as a significant category regarding this question.

DISCUSSION

The data demonstrated that most Internal Medicine residents (75%) reported experiences with psychiatric patients in a general hospital and around 63% had mental health care training during undergraduate medical school. Nevertheless, they showed higher stigma indexes related to factors such as fear and anger, attributing characteristics such as unpredictability and aggressiveness to the patients with mental disorders, as well as demonstrating higher degrees of anger and guilt due to their disorders when compared to psychiatry residents (Table 2).

These findings suggest that the simple exposure to psychiatric patients and mental health contents of the undergraduate medical school curriculum may not satisfactorily contribute to reduce stigma and prejudice related to mental disorders6. The scientific literature shows discordant results, whether with an increase or decrease of prejudice after the completion of the psychiatry internship during the undergraduate medical course6),(12. Probably, the relationship between teaching and the stigma is influenced by the quality of the curriculum taught, faculty attitudes and the health context in which these professionals are being trained6),(12.

If, on the one hand, psychiatry in the medical curriculum contributes to the acquisition of new knowledge and the correction of preconceived concepts, more stereotyped attributions such as unpredictability, avoidance, possibility of violent acts and inability to cure have a lesser variability degree after having contact with mental health during undergraduate medical school. Therefore, the increase in knowledge is not automatically followed by the reduction in stigma and discrimination13. It was also observed that the higher the residency year, the lower the anger rate of students towards patients with mental disorders (Table 3), probably due to other variables not attributable only to the acquisition of technical knowledge.

Factors that precede the actual medical training may contribute to the construction of prejudice and prevent potential attitude changes that may be attained through training6),(14. Among them, there are socioeconomic conditions, previous knowledge about mental health, familiarity with the provision of care to these patients, personal or family experience with psychiatric illness, attitudes from parents and the local culture and contact with this population6.

The aspects of stigma that showed the highest means in the attribution questionnaire among internal medicine residents were avoidance and coercion (Table 2). These attributes represent, respectively, the desire to not have contact with patients with mental disorders and the obligation to follow treatment regardless of one’s will. However, the literature demonstrates that the desire for social distancing and authoritarian behaviors towards psychiatric patients prevail in other groups, such as mental health professionals and even psychiatrists2),(15.

Patients with mental disorders commonly need continuous follow-up by general practitioners, as they are more likely to develop chronic conditions16, but a decrease in the approach of these patients has been observed outside the psychiatry field17. Difficulties and negligence in the clinical approach of these individuals reflect gaps in the health care network and medical training17. This deficiency may be contextualized in part by the quality of the experiences with psychiatric patients that happen during the undergraduate course, which occur primarily in acute clinical circumstances and without monitoring the processes of rehabilitation or reintegration into the community13.

It is interesting to note that, when asked about training to provide care to psychiatric patients, the category related to care responsibility surpassed the reports on training gaps and difficulty to validate patients’ complaints (Chart 2). The data represent the understanding that the psychiatrist and specialized environments are the sole responsible for the management of these patients. This perception exempts the non-specialist physician from the responsibility of comprehensive care for the mentally ill, contrary to the principles of the current guidelines for medical training18),(19. It is also noted that there are few publications that address the care provided to patients with severe mental disorders admitted to a general hospital due to clinical and/or surgical complication17.

It is known that patients with clinical conditions are at high risk of developing mental disorders and use internal medicine services more frequently20. Clinical comorbidities in patients with mental disorders are frequently observed, reaching 80%. Similarly, psychiatric disorders are found in approximately 30% to 60% of patients with physical conditions21, i.e., clinical treatments offered to people without psychiatric disorders should be equally offered to patients with mental illness16. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities significantly increases the costs of hospitalization, reflecting worse adherence to the proposed treatment, increasing rates of complications, mortality and hospital length of stay, thus demonstrating difficulties in managing this individual in clinical units20)-(23. It is noteworthy that mortality rates in this population are at least twice as high as in the general population. Despite this, medical needs are commonly neglected16.

Certain psychiatric medications cause side effects, increased cardiovascular risk, induction of obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome16, but unfavorable outcomes when assisting patients with mental disorders cannot be fully explained by lifestyle and significant metabolic changes caused by some psychotropics24, suggesting an important influence of stigma on this population. Certainly, avoidant or negative behaviors towards psychiatric patients may have consequences for the quality and completeness of the services provided to them17.

Outsourcing the care responsibility was even more significant in cases of mental disorders considered to be more severe, such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder (Chart 2). This fact may be justified by the greater attribution of dangerous behaviors to these individuals, stimulating the desire for distancing and a greater level of skepticism regarding prognosis improvement2),(3.

A significant percentage of physicians feel unprepared to meet the demands of mental health patients, probably due to training gaps during undergraduate medical school19. Topics related to mental health and psychiatry are approached superficially, sometimes outside the social and community context and with an eminently curative approach19. In certain cases, the training takes place in negative contexts, which contributes to reinforce stereotypes regarding psychiatric care, creating resistance that hinder the availability of general practitioners to provide care to patients with mental disorders19.

Internal Medicine residents, when asked about the experience of providing care to individuals with mental disorders, claimed that the difficulty to legitimize or validate the patient’s complaint was the main obstacle. This category surpassed negative feelings, training gaps and care responsibility (Chart 1).

A literature review aimed to organize the knowledge related to health professionals’ stigma towards patients with mental illness disclosed, among its results, the perception, by part of the population, that other disorders such as depression can be seen as something natural and would not need medical care. In contrast, doctors themselves list these problems as less important than clinical problems, leading to potentially severe consequences2.

This difficulty may be minimized with strategies that provide qualified listening of the patient, their family members and caregivers, seeking comprehensive and humanized care. According to the curricular guidelines for health education, graduates from different courses in the health field must have “generalist, humanistic, critical and reflective, ethical and transformative training, committed to improving the quality of life and health of the population”. Therefore, the objective is to favor the construction of bonds and an empathic approach, based on a doctor-patient-health professional relationship qualified by the problems reported by individuals, families, groups and communities. Universal access and equality are sought as a right to citizenship, without prejudice of any kind, meeting specific personal needs, according to the priorities defined by vulnerability and risks to health and life. Finally, the training is committed to overcome the inequities that cause illness in individuals and communities25.

When assessing the results of the questions, it is noted that the gaps in training were not highlighted when analyzing the residents’ answers to the questions related to their training and perceptions of care (Charts 1 e 2). This finding suggests that these gaps, although significant, do not surpass the low perception of the physician as responsible for care and the difficulty in legitimizing these patients’ complaints. Thus, the need to find strategies to modify this reality is reinforced, seeking to optimize the professionals’ ability to collect information about psychological suffering, beyond the approach focused on theoretical curriculum content.

Although the stigmas of medical professionals and students towards patients with mental disorders have been widely studied in the literature, strategies based on scientific evidence to reduce this stigma are still scarce14. It is a complex phenomenon to be understood, originated from social stereotypes previously acquired by students and which were not deconstructed during the training period or were even intensified during this period13),(26. These stereotypes have consequences not only for psychiatric patients, but interfere in society as a whole26.

Although education about mental illnesses has the potential to reduce stigmas towards the patient, this decrease does not seem to have lasting consequences and tends to primarily influence people more likely to have contact with these individuals5),(26. On the other hand, the relationship with members of a stigmatized group has been shown to be an effective way to reduce prejudice, causing changes in behavior and attitudes for a longer period5),(26.

It is, therefore, urgent to foster curricular changes and strategies to facilitate the interaction of residents and medical students with psychiatric patients, resulting in greater familiarity with their demands. The mental health approach during medical training needs to promote communication skills, develop technical competence in assistance with the collection of qualified information, transform attitudes that provide empathic relationships, as well as foster the perception of the need for comprehensive patient care from the biopsychosocial and spiritual perspectives.

CONCLUSION

The collected data allowed us to conclude that Internal Medicine residents report gaps in training during the undergraduate course that make providing care to psychiatric patients difficult. However, these gaps are less important than the low perception of the physician as responsible for the care and the difficulty in legitimizing complaints of these individuals.

It is also noteworthy that internal medicine residents, despite having contact with psychiatric patients during the undergraduate course and residency, have higher rates of stigma than psychiatry residents, with emphasis on aspects such as fear and anger.

This study discloses the need for educational interventions that seek to train Internal Medicine students and residents to provide care to patients with mental disorders, providing a greater understanding of the need for comprehensive and empathic care for this population.

One limitation of this study is the restricted number of participants from a single Residency Program in Internal Medicine. However, it is a traditional Program, linked to the oldest medical school in the interior of the state of São Paulo. Also, a percentage of participation close to the total possible sample number was reached and the values necessary for carrying out a reliable statistical analysis were met. Another consideration is that the need to recall previous situations, which sometimes occurred during the undergraduate course, may result in memory bias, which can influence the interpretation of qualitative data. This risk was greatly minimized through qualitative analysis from two different angles: content analysis proposed by Bardin and Pareto charts.

The present study differs from the available literature on the topic as it chooses a poorly studied population regarding the subject of teaching and attitudes in mental health, despite the evident need to problematize this context. The use of different approaches, with a validated quantitative instrument and qualitative assessment strategies, provided a depth of reflection that only studies of this nature could do.