INTRODUCTION

In 2020, due to the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, schools closed their doors due to health reasons1. Shortly after the interruption of classes, several of them adapted their teaching methods to the remote modality. Suddenly, the educational environment underwent a drastic change, bringing to teachers and students the challenge of teaching and learning in a social distancing scenario. This change of direction took place amidst doubts, uncertainties and anxieties on all sides.

In medical schools, this situation has become more of a concern, as medical training, due to its social and academic nature, is usually a source of stress for the students2. Literature review studies3),(4) and a nationwide investigation carried out in the United States5 showed that the prevalence of stress among medical students was significantly higher than in the general population, with younger students being the most affected ones. In Brazil, a systematic review study6 carried out in 2017 showed that approximately 50% of medical students reported psychological stress, which, when there is a lack of coping resources, causes disappointment with the professional choice, mental suffering and compromises school performance.

The concern with medical students was also justified by studies on the implications of the pandemic on the students’ mental health7)-(9. The social isolation resulting from the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, as well as the changes from in-person to remote and distance learning, increased the prevalence of depression, anxiety and behavioral disorders among university students. These facts reinforced the need for the medical school to offer students some type of care.

Among the possible offers, we highlight the student mentoring programs by teachers who, with their experience in life and the profession, are able to help students to follow the academic pathway with a little more emotional security. Reviews of the medical literature10),(11 identify mentoring as the practice of offering empathic and developmental support for self-care, well-being and resilience. The results presented in these studies10),(11 showed an improvement in the students’ quality of life and the development of relational skills, albeit with the exception that mentoring programs would need to improve their assessment methods aiming to produce more robust impact evidence. Also in Brazil, studies have shown good results of mentoring programs in medical education12),(13. Student mentoring is, therefore, a strategy for developing skills to face the difficulties inherent to medical training, which strengthens the construction of the future physician’s professional identity, respecting their personal characteristics and needs.

Given these considerations, amidst the SARS-COV-2 pandemic and the perceived strong impact on medical education and on the teacher-student relationship determined by social distancing, a group of teacher-mentors from a mentoring program already implemented for 2 years, adapted its on-site mentoring activities to a remote model, aimed at students who were already participating in mentoring, and separately for students attending the first semesters of the medical course. For upper-level students, the objective was to continue the program and maintain the benefits it had already provided them. For the first-year students, the objective was to offer welcoming and support services to deal with the changes in life represented by admission to the medical school in a situation of social isolation. This remote mentoring experience was reported and analyzed in this article.

EXPERIENCE REPORT

The medical school where the experience took place is a new school, of which teaching standards were assessed by the Ministry of Education (MEC), obtaining a grade of five (maximum grade). It is a private institution, located in the city of São Paulo, whose main characteristics, according to its students, include being a welcoming place where, in general, the teacher-student relationship is a good and close one. This aspect is very important in medical education, in which the teacher is a model for the fundamental humanistic formation of medical practice14.

As an example of this proximity, the mentoring program itself, created in 2018, was carefully designed together with the students. Through several conversation circles, students were able to choose the mentoring model best suited to their expectations and needs, as well as to help choose the teacher-mentors. Twelve teachers were chosen based on qualitative criteria defined by: commitment to medical education, being empathetic and communicating well, being recognized by students as a good teacher, being empathic and willing to be a mentor. A mentor preparation course was carried out, using active methodologies, considering the development of the following skills for the mentor’s performance: 1. being a careful listener, 2. coordinating a conversation circle, 3. stimulating critical thinking, 4. identifying bias in the construction of thought in medical education, 5. carrying out effective and empathic communication. The final model of the mentoring program was created with the participation of the mentors responsible for its structuring.

The program thus constructed adopted a cultural extension characteristic, counting as a complementary activity that accumulates credits, offered every six months to students who are interested.

Mentoring for Upper-level Students

It comprised 10 groups of upper-level students from different academic periods, who joined the groups by free choice and affinity with the mentor.

Before the pandemic, mentoring meetings took place in person as monthly conversation circles at a time and place scheduled by the program coordination. The topics of conversation were free, brought by the students and treated by the group in a welcoming and reflective manner, seeking to broaden the understanding of the topics and, if relevant, to create collective responses to the problems.

In this model, it is not the mentor’s responsibility to give answers based on their opinions, but to encourage the group to think and find ways to deal with the daily life of being a medical student and, in the future, a physician, supporting the students to face their difficulties. However, very often it is important for the mentor to draw from their own experiences, memories and life history, bringing students a living testimony of biographical meanings.

Mentoring for First-year Students

Regarding the students that have just started the medical course, seen as potentially more prone to disorientation and stress, and who after two weeks of admission had to adapt to an unknown environment and remote teaching, 9 groups of first-year students were created in the first semester, and 8 groups in the second semester, with a monthly meeting schedule specifically created for them. The groups were randomly formed, as the students knew little about the teachers, peers and even the mentoring program. The topics remained free but based on previous experiences of psychopedagogical assistance to first-year students; the chosen topics were the ones that could be addressed by mentors if they seemed appropriate to the group, such as: choice of medical career, changes in the life of high school students to college students, how to organize oneself to study.

Adaptations to virtual mentoring

The adaptation to the remote format maintained the proposal of being a “place of conversation”, but to facilitate the meeting, it was decided to use the time provided for in the curriculum or at the convenience of students and mentors. The Zoom platform was chosen because it is an institutional choice for remote activities.

As before the pandemic, the technical follow-up of the mentoring program took place through meetings of the mentor group with the program coordination, and consultation with the students through a self-administered online questionnaire with closed questions and answers provided on a Likert scale and open questions with discursive responses. Follow-up meetings took place remotely. During these follow-up meetings, there was a written record of the mentors’ opinions and perceptions presented as free narratives about the working of the groups and the issues brought up by the students.

The data obtained from the questionnaires answered by the students and from the records of the meetings with the mentors were submitted to content analysis and triangulated to complement the program’s evaluation and monitoring results.

Experience Results

Descriptive Analysis

From March to December 2020, 109 virtual mentoring meetings and 10 monitoring meetings between mentors and coordination were held, and 110 students that participated in the program answered the evaluation questionnaires.

The numerical participation of students from the first period (first-year students) in the first and second semesters of 2020 and other students (upper-level students) in mentoring is shown in Frame 1.

Frame 1 Absolute and relative numbers of first-year and upper-level students who participated in virtual mentoring from March to December 2020.

| Time in medical school | Enrolled | Mentoring | Participation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | ||||

| First semester | Second semester | First semester | Second semester | First semester | Second semester | |

| First-year students | 82 | 108 | 58 | 89 | 70 | 83 |

| Upper-level students | 720 | 95 | 13 | |||

| Total | 910 | 242 | 27 | |||

The number of students per meeting ranged from 1 to 10 students, depending on the group, with an average of 5 students per group. In the 10 groups of upper-level students, participation took place according to the same pattern as in the in-person meetings. In some groups, mentors observed an increase in the number of participants in virtual meetings compared to the in-person meetings.

Frame 2 shows the students’ satisfaction regarding the items: 1. Quality of discussions and reflections, 2. Mentor’s performance, 3. Embracement, environment and emotional support, according to their answers to the program evaluation questionnaires.

Frame 2 Percentage of “very good” and “good” responses on a Likert scale (very bad, bad, good, and very good) for items related to student’s satisfaction with virtual mentoring from March to December 2020. N=110.

| Analyzed Element | Very good | Good |

|---|---|---|

| Discussions and reflections | 70.0 | 29.1 |

| Mentor’s performance | 93.6 | 5.5 |

| Environment and emotional support | 81.8 | 18.2 |

When asked to provide a score from 0 to 10 for the remote meetings of their groups, virtual mentoring obtained an average score of 9.36.

As for the preference for the modalities, 22% of the students said they prefer the in-person modality, 25% the remote modality, and the majority, or 53%, said they prefer the hybrid modality (in-person and remote).

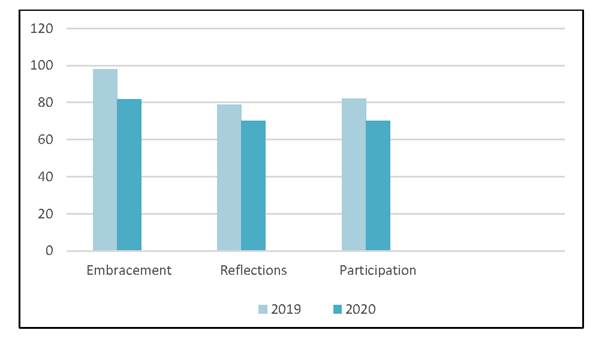

Despite the good evaluation of virtual mentoring, when comparing the responses of upper-level students in 2019 with those in 2020, there was a small difference in favor of the in-person modality, as shown in Chart 1.

Content analysis

Mentors reported that remote meetings were well accepted by students, a perception confirmed by students in the questionnaires. Overall, students felt free to speak, offer opinions and discuss issues. This interactive resourcefulness varied between the groups, but it was observed to be facilitated in groups of students and mentors who knew one another previously. The groups of first-year students in the first semester demanded from the mentors a more active approach to facilitate interaction, whereas the group of first-year students in the second semester was quite comfortable and actively participated in the meetings.

The mentors’ attention was drawn to the difficulty of some students have to turn on the camera, a fact that has been recurrently observed in remote teaching. Even in the mentoring meeting, which is by definition a more “protected” space, especially in the first semester of the year, it was difficult to get the students to accept exposing their image. In the second semester, there was a greater number of students with the camera on. In some groups it was evident that the turning on of the cameras took place when the students realized that the mentoring space was still “protected” in the remote environment as well. In other groups, students turned on the cameras when they felt confident in exposing part of their more personal life, reserved for the home environment.

In the content analysis about the narrative data from mentors and students’ discourse - considering 17 groups of first-year students, and separately, 10 groups of upper-level students - the recurrent content in the meetings was agglutinated into two analytical categories: 1. Concerns with academic life, 2. Concerns about one’s life and the life of others, as shown in Frames 3 and 4.

Frame 3 Analytical categories related to recurrent content in virtual mentoring meetings for first-year students from March to December 2020.

| Concerns about academic life |

|---|

| - Excess of remote activities and difficulties in organizing time to study. |

| - Fear of the academic unknown, especially of tests and performance requirements; and consequently fear of failing the semester for not being able to study enough and not learning everything they need to learn. |

| - Doubts about whether it is actually possible to learn medicine through distance education. |

| Concerns about one’s life and the life of others |

| - Need for many adaptations in family life to “fit” the academic life into the routine at home. |

| - Concerns about the family’s financial situation (self-employed parents without income or parents with an employment contract, but with a reduction in salary). |

| - Relational difficulties with parents who, working as home office, work more hours than they normally do, having little time to pay attention to them. |

| - Fear of parents getting sick, mourning and sadness for sick relatives or relatives who died of COVID-19. |

| - Life during the pandemic, being tired of staying at home, and other things they would like to do besides studying Medicine. |

| - Desire to return to life outside the home, to college, to classes, to parties, but fear of being contaminated and bringing the virus into one’s home. |

Frame 4 Analytical categories related to recurrent content in virtual mentoring meetings for upper-level students from March to December 2020.

| Concerns about academic life |

|---|

| - Difficulties adapting to distance learning but gaining skills in the use of communication technologies. |

| - Excess of activities in several disciplines, difficulty in organizing time, tiredness, stress and exhaustion resulting from this excess. |

| - Difficulty studying at home, as family members require them to help with household activities. |

| - Concerns about the reduction of practical classes and its impact on learning. |

| - Distress for not knowing what the internship will be like amidst the pandemic, and whether they will be able to prepare for the residency tests, and what their professional future will be like. |

| Concerns about one’s life and the other’s |

| - Need for many adaptations in family life to “fit” academic life into the routine at home. |

| - Concerns about the family’s financial situation (self-employed parents without income or parents with employment contracts, but with a reduction in salary). |

| - Fear of parents getting sick, mourning and sadness for sick relatives or relatives who died of COVID-19. |

| - Fear of the pandemic, of disease, of death and what the post-pandemic future will be like. |

| - Distress arising from doubts about how long the pandemic will last. |

| - Desire to return to life outside the home, to college, to classes, to parties, but fear of being contaminated and bringing the virus into one’s home. |

The contents related to an excess of activities in the disciplines, concerns for the family and fear of the pandemic were common among first-year and upper-level students. First-year students reported more difficulties in managing the time to study and doubts about the daily life in college, while upper-level students were more concerned about the lack of practical classes, internship and how well they would be able to prepare for the residency tests.

For mentors and students, virtual mentoring was an important support for the student in the face of social distancing resulting from the pandemic.

For first-years, the meetings were good for sharing ideas, stories, expectations and fears. It had the effect of bringing them closer to classmates and the school, considered to be still “very distant” from their reality. They also stated that the meetings allowed the exchange of experiences that could be very distressing if experienced in a solitary way.

For upper-level students, the meetings decreased the feeling of being lost, and helped them to deal with their anxiety, to not feel alone in their doubts and problems. These students reinforced the importance of mentoring for bringing students and the school closer together, in addition to facilitating the exchange of experiences and the solution of problems in the academic routine.

REFLECTIONS ABOUT THE EXPERIENCE

Mentoring as an institutional program15 signals the medical school’s commitment to good academic training, combined with the student’s emotional support. By promoting mentoring, the medical school cultivates closeness between people, relationships of belonging, mutual help, and the institutional culture of human development.

The mentoring meetings are characterized as spaces for the production of intersubjectivity11),(15, as the participants establish relationships of understanding the different life histories, values and expectations of being a physician. This construction takes place through ethical and empathic communication, in which the acts of speaking are valued and recognized among all speakers14. For this, the relationship of trust between the mentor and the group is vital for everyone’s participation. In it, students feel safe to tell their personal stories, to bring up difficult and delicate problems, and to seek in the mentor’s life experience the possibility of building a path for themselves.

In the case reported here, the first question that arose, considering the impossibility of maintaining face-to-face meetings, was how much the transposition to the remote model would allow for intersubjectivity. The experience proved to be a difficult issue that, however, needs to be faced. Notwithstanding the fact that the meeting is established through a technological interposition that subtracts the sensory density of the real contact, the fact that the students keep the cameras off, also subtracting the image contact, impairs the communication. The absence of visual non-verbal language makes it difficult to recognize feelings, emotions, and signs that impact on the building of bonds, transmission and understanding of verbal utterances.

The reasons why students so often do not turn on the cameras is a topic that goes beyond the limits of this experience, but deserves to be investigated, mainly, considering that remote interaction tends to be incorporated into post-pandemic teaching. A discreet clue that appeared in this experience refers to the need to establish trusting relationships between people during the remote meeting.

Still, the virtual mentoring meetings were rated very good by both students and mentors. During the mentoring of first-year and upper-level students, students felt cared for, supported and grateful. The mentors also shared the perception of satisfaction with the meetings. That is, there was a good interaction between people, resulting in noticeable beneficial effects.

These observations are in line with studies11),(13),(15 that recognize mentoring as an important space for the redefinition of student experiences, reinforcing its prescription in medical courses, with the difference that such studies took place in real-classroom environments, while in this experience , we deal with the topic in a remote environment.

This result points to the need for further questions about the ways of constructing subjectivity in postmodernity14 in a media-related, technological, subjectivist world, and still somewhat unknown to its contemporaries, regarding the long-term effects on the production of personality, a central topic in mentoring programs.

Another issue that emerged from this virtual mentoring experience was the ethical dimension of the meeting. In whatever format they are adopted, mentoring meetings must be sealed by agreements of secrecy and confidentiality of the subjects dealt with in the group. In practice, these agreements also seal the group’s viability, because without the security to speak, there is no talking of issues that are actually of interest to the group.

In the remote modality, the secrecy and confidentiality agreement was maintained, but it should be noted that the virtual environment is an environment with less control, as it can be recorded, filmed and then manipulated without the people involved being aware and agreeing with it. The mentor must be aware of it and reinforce the ethical discussion with their group of students, seeking a stronger and more conscious commitment on the part of everyone about the responsibility to protect the meetings and respect ethical limits, which is an important learning for the personal and professional life.

The experience of virtual mentoring in times of social isolation due to the SARS-COV-2 pandemic showed to be relevant and promising. The questions raised herein for reflection, as well as the relatively short period of experience, are limitations of this study that should be considered and indicate the need for further and future investigations on the subject.

texto em

texto em