INTRODUCTION

Human Rights (HR) are prerogatives inherent to the human condition, considering all aspects of life: the right to life, education, freedom, religion, security, and work1. It is important to establish the HR culture in educational institutions as a way to contribute to the dynamics of interpersonal relationships and, therefore, the educational environment2. Teacher development on HR is essential and for this process to occur, understanding the experiences in the academic environment becomes an important step.

In Brazil, HR were institutionalized through the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, called the “Citizen Constitution”. However, even though the country has ratified most of the global and regional instruments for HR protection, there has been no effective implementation of such rights in the national territory3.

Human Rights Education (HRE) would potentially enable people to respect human beings, their dignity, democratic values, tolerance, and a harmonious coexistence according to the norms of the rule of law, contributing for the population’s taking a protagonist role in their history3.

In line with the World Programme for Human Rights Education, Brazil established the National Human Rights Education Committee (Comitê Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos), resulting in the creation of the National Human Rights Programs (PNDH, Programas Nacionais de Direitos Humanos) and the National Human Rights Education Plan (PNEDH, Plano Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos)4.

According to the PNDH, HRE is a systematic and multidimensional process that guides the formation of the subject of law, articulating several dimensions such as the apprehension of knowledge historically constructed on HR, the affirmation of values, attitudes and social practices that express the culture of HR in all areas of society4.

The PNDH and the PNEDH also aim to give visibility and access tools to the rights arising from the treaties and conventions ratified by the country through the axes of basic education, higher education, non-formal education, education of professionals in the legal and public security systems and education in the media5.

Regarding Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), they have an evident duty to participate in the construction of a culture of HR promotion, protection, defense and repair through the inseparable principles of teaching, research and extension, aiming to train social agents committed to the future of society, with the objective of promoting development, social justice, democracy and peace6)-(8.

Some HEIs are already recognized for their work on EDH since the 1990s. One example is the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RIO), through the Department of Law, which established the topics of HR, ethics and citizenship as a line of research, implemented HR at the discipline level, and created associations with foreign institutions, such as the Inter-American Institute of Human Rights2. However, it is worth mentioning that in the researched databases: Medline, SciELO, Lilacs and Cochrane, using the following descriptors: direitos humanos (human rights), educação em direitos humanos (human rights education), DH (HR), no studies were found that addressed the issue of HR and HRE in HEIs in the health area.

It should be noted that for the establishment of the HR culture in the HEIs, it is essential to have the participation of a faculty that understands and respects not only HR but also fundamental freedoms and personal and collective responsibilities, knowing how to differentiate episodes of violence and social vulnerability with autonomy and critical sense, developing, based on this distinction, actions to promote (education and culture), protect (norms of coexistence, mediations and knowledge of rights and duties) and defend such rights in the academic community6; this importance is even more accentuated when the HEI uses Problem-Based Learning (PBL) as a teaching methodology, since working in small groups expands the tutors’ perception of HR issues among the students during a tutorial group9.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an active methodology in which the students must develop proactivity and autonomy to become the protagonists of their learning. The PBL is carried out in small groups, called tutorial groups, consisting of 10 to 12 students and a tutor, whose main role is to facilitate the learning process. There are four fundamental educational principles that support this methodology and translate into learning: constructive, collaborative, autonomous/self-directed and contextual. This methodology proposes the development of other skills beyond the cognitive domain, such as communication, learning to learn, group work, interpersonal relationships and respect for others, among others10)-(13.

Therefore, contributing to the culture of HR in HEIs is essential to establish a good educational environment, in which the learning processes are effective for the training of technically competent, ethical and humane professionals. In this sense, the objective of this study was to understand the meanings attributed by tutors to experiences involving HR in the academic environment as the first step towards establishing teacher development in this area.

METHODS

A qualitative study was carried out, in which a speech space was offered for the tutors to express the meanings attributed to their experiences involving HR issues in the academic environment, more specifically in the development of the tutorial group.

The study was carried out at Faculdade Pernambucana de Saúde (FPS) which uses the Problem-Based Learning methodology. In order to continuously improve the performance of tutors and coordinators, FPS has implemented the Teaching Development Committee (CDD, Comitê de Desenvolvimento Docente), which is responsible for preparing the tutor for the exercise of their functions, tasks, and so forth, being one of its current goals to implement the culture of HR in the academic environment. The study was carried out between December 2019 and September 2020.

The data collection was carried out through Focal Groups (FG). For operational reasons, due to the current health situation related to the COVID-19 pandemic, two FGs were held with three participants each, one in person and the other remotely, using the Cisco Webex platform. Therefore, in the end, a total of six tutors participated. Despite the small number, since FPS has 73 medical tutors working in tutorial groups, the idea that, in qualitative studies, the representativeness of the speeches is taken into account is reinforced, that is, the information provided by people involved in a research topic can represent the group of people from the community to which they belong and experience the same context, involving the object of study.14

The two groups used the same script and the same moderator and external observers participated. FPS tutors were selected intentionally, who were regularly exercising their tutor role during the FG. Aiming to maintain the study confidentiality, we chose to use aliases in the results/discussion sections of the article to preserve the participants’ identities.

The FGs took place according to the following steps: resources were provided: appropriate space, consisting of a neutral territory and of easy access to participants, protected from noise and external interruptions. Required equipment: two recorders, whose use was subject to the express permission of the group’s participants. Duration of the FG: the degree of controversy related to the aspects under discussion and the need of the group were considered, but the duration varied from 90 to 110 minutes15.

The moderator’s role and the dynamics of the discussion: moderator: the starting condition is that they have substantial knowledge of the topic under discussion so they can lead the group adequately. A person with experience in the subject of HR and external to the group of participants was invited. External observers: they do not manifest during the discussion and seek to capture and record the participants’ reaction. Two external observers with experience in conducting FGs were invited. Moderator duties: introduce the discussion and maintain it; emphasize to the group that there are no right or wrong answers; observe the participants, encouraging each of them to speak; look for thematic opportunities of the discussion itself; build relationships with the informants to individually develop the responses and comments considered relevant by the group or by the researcher; observe the non-verbal communications and the participants’ own rhythm, within the time allotted for the debate15.

The group’s objective was clearly expressed at the time of the opening of the activities, signaling the central issues on which the discussion would focus. After the participants’ presentation, the basic rules of groups operation were specified, clarifying the moderator’s role.

The following basic list of rules was adopted: only one person speaks at a time; prevent parallel discussions; speak what you think freely; prevent any members of the group from dominating the discussion; maintain attention and discourse on the addressed topic

The moderator also ensured that all participants had previously signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF), which included the reference to the use of recorders or cameras.

The theoretical analytical categories16 were predefined based on the adopted theoretical framework, that is, in the PNEDH, The Human Rights Education Manual (CEDH, Caderno de Educação dos Direitos Humanos), in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in articles addressing the topic17)-(23. These categories were maintained as they were identified in the analysis of the participants’ speeches. The empirical analytical categories refer to speech contents that were not previously identified, but which were considered relevant to the apprehension and understanding of the meanings brought by the participants in relation to the study topic24.

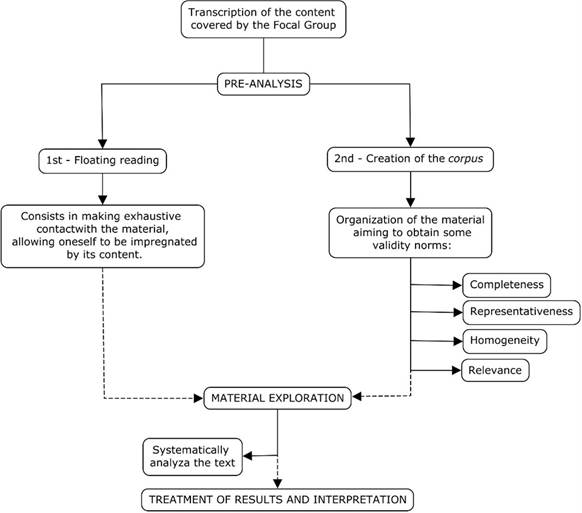

After the full transcription of the contents recorded during the discussion in the FG, their analysis were carried out based on the adopted theoretical framework17)-(23) (Figure 1), and the following steps were followed, according to Bardin content analysis technique in the thematic modality24),(25: Pre-Analysis: organization of the material produced through interviews and theoretical material; immersion in the raw data to be impregnated by their content; identification of concepts from which the materials were assessed and referenced based on the study analysis objectives (individual/vertical depth); Exploration of the material: the content of the speech was organized by categories, as well as recurring, similar aspects (horizontalization), illustrated by transcriptions, cores of meaning and central topics with subcategories (cross-sectional analysis of the material). Treatment of the obtained results and interpretation: the researchers made inferences and interpretations of the speeches based on the theoretical framework24.

The interpretation was carried out, with careful and permanent discussion by the researchers, favoring the subjectivity apprehended from the context of the speeches and always anchored in the adopted theoretical framework. Therefore, the material was analyzed and discussed, seeking saturation.

Sampling closure by theoretical saturation is operationally defined as the interruption of new participants’ inclusion when the obtained data start showing, based on the researcher’s assessment, a certain redundancy or repetition, with data collection being considered non-relevant from then on.

The assessment of theoretical saturation based on a sample is carried out through a continuous process of data analysis, starting at the beginning of the collection process. Bearing in mind the questions posed to the interviewees, which reflect the research objectives, this preliminary analysis seeks the moment when the addition of data and information does not change the understanding of the study26.

Therefore, the development of two different FGs, using the same theoretical categories, did not harm the present study. It can be observed that none of the speeches is the same as the other; however, they all have elements in common. Initially, the addition of information is more evident among the speeches. Subsequently, such addition fades away until it ceases to occur26.

The study complied with the ethical criteria of Resolution n. 510/2016. The project was approved by CAAE under number: 22696919.3.0000.5569.

RESULTS / DISCUSSION

The study sought to understand the meanings attributed by tutors to their experiences involving HR issues in the academic environment. In total, six tutors participated, five females and one male, of which three were from the medical course (Freire, Anita and Raquel), one from the Pharmacy course (Anália), one from the Nutrition course (Maria), and one from the Physiotherapy course (Cecilia).

The analytical categories were defined based on the theoretical framework related to HR, according to PNEDH, CEDH, Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in articles dealing with the topic17)-(23, comprising the following: gender and sexuality, communication and freedom of expression, social minorities, and student stigmatization and self-esteem. During the process of reinterpretation of the speeches, the following subcategories were identified, considered to be empirical: ableism, fatphobia, mental health, psychophobia and interpersonal conflicts.

Below are the tutors’ statements, their interpretations according to the identified categories and subcategories of analysis and the articulation with the adopted theoretical assumptions related to HR.

Category 1: gender and sexuality

Femininity is the set of characteristics attributed to women for belonging to the female gender, such as sensitivity, passivity, understanding. While masculinity includes adjectives such as aggressiveness, domination, insensitivity27.

In this sense, Anita reported a discussion involving a divergence between students as an example of the lack of embracement of differences and, at the same time, promoting a gender conflict, through the use of the voice, resulting in oppression: “[...] he had a very strong voice [...], and then there was this girl, who was a skinny girl, who talked a lot about religion and, he, who had his own religion... You could see that he clearly overpowered her using his voice and he would not let her finish [...]”.

The imperative use of one’s voice and/or behavior as a way of imposing one’s ideology can constitute a type of violence, since violence is not limited to physical aggression, but also manifests itself through verbal, psychological, moral or patrimonial attitudes27.

From the perspective of sexuality and its definition as a set of biological, psychological and social aspects, diversity comprises ways of experiencing and expressing sexuality28. In this context, sexual orientation and gender identity are social determinants of health for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transvestite and transsexual individuals (LGBT). Consequently, discrimination and prejudice aggravate suffering and illness, as the health problems of this population segment are complex and their demands are numerous29),(30.

However, a major obstacle is the prejudice reproduced by the health professional, which discourages seeking for medical care by the LGBT population and induces the lack of truthfulness regarding the information collected in the anamnesis. This is evident when 40% of women do not mention that they are lesbian or bisexual when seeking medical care. Moreover, among those who did mention it, more than 50% reported discriminatory or surprise reactions by the professional29),(31.

In this context, Cecília mentioned a situation in which the student stated that he would refuse to care for homosexual couples. She was worried, as she would often not know how to handle these cases:

“[...] we were talking about the therapist-patient relationship, and if they had to treat patients who were homosexual couples, and then this student said they would not accept it, they would not assist them[...] these are issues that are raised in tutoring that we often don’t even know how to deal with [...]” - Cecília

Assuming that one of the purposes of higher education is to maintain a relationship of service and reciprocity with society4 and that one of the principles of the Brazilian Unified health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde) is universality, which comprises “guaranteed access to health services for the entire population [...] without prejudices or privileges of any kind”32, it becomes necessary for students attending courses focused on health to be encouraged to free themselves from prejudice while attending undergraduate school33.

Cecília also stated that she was unprepared to deal with issues related to HR, especially with the conflicts that may occur due to divergent beliefs. She stated that she sees tutorship as an opportunity to address these issues, even if they are outside the objectives previously stipulated according to the curriculum matrix: “[…] I would like to have an opportunity to say: now, let’s talk about this here! It is over, let’s do a tutorial about it, we are going to discuss it from here, it wasn’t, necessarily the objective, that wasn’t the objective of that tutorial”.

The tutor seemed willing to discuss HR during the tutoring session but did not do it. This may reflect a lack of familiarity with the topic. In this sense, it is essential that educators be instructed about the culture of respect for human rights because, through this knowledge, they will be able to perform a better critical interpretation of the academic environment, aiming to detect scenarios and intervention opportunities and guarantee the applicability of the principles contained in the national guidelines2.

Category 2: communication and freedom of expression

Interpersonal communication is an essential tool for coexistence in society. It can be expressed both verbally and non-verbally34. The Constitution of 1988 guaranteed the right to freedom of expression of intellectual, artistic, scientific and communication activities, as long as there is no disrespect to the other guaranteed rights35. Thus, it can be observed that communication and freedom of expression are connected and that some expressions or gestures are loaded with prejudiced and discriminatory meanings.

During the FG, Freire addressed the topic of interpersonal communication, addressing some situations of misunderstanding generated by misinformation: “[...] sometimes I perceive more as a matter of misinformation, and then some things come out, like, socially accepted, but wrong from the point of view of respect [...]”.

Words, phrases or comments that sometimes seem naive can have undesirable and offensive effects36, such as: the word homosexuality in Portuguese (homossexualismo) in which the suffix “ismo” which is compatible with “ism” and has a pathological connotation37; the word “nightstand” in Portuguese (“criado mudo”), which refers to the slave who used to stand by the bed of their owners or masters in the colonial days36. Therefore, it is imperative that the Freedom of Expression that we are allowed through communication does not become disrespectful.

On the other hand, the correct use of terms and expressions when referring to minority social groups can help to legitimize these social movements, in order to fight stereotypes and respect individualities37.

In another sphere, Cecília suggested that the political topic should be encouraged and debated among students as a learning tool. She stressed that this approach must be a healthy one, while maintaining respect, aiming to take politics to something that is beyond a polarizing debate.

“I think we could talk more about this, OK, politics in the broad sense, right, us, education, health, all of this is politics [...], if we talk more about it, I think we are more aware of the rights, you know, of duty, of citizenship, which is also a role, isn’t it, of the College [...]” - Cecília

The HRE aims at the full development of the individual, their preparation for the exercise of citizenship and work qualification2. Since the 1988 Constitution, the foundations of the government are based on citizenship, human dignity, and political pluralism35. These foundations, in line with the current conception of HR, encompass not only political and civil rights, but also economic, social and cultural ones. Therefore, it is important that there be a construction of values based on HR so that an active citizenship can be exercised, in which the citizen with rights and duties is an agent of transformation and fights for a just society38.

Category 3: social minorities

There is no internationally accepted concept of which groups belong to social minorities. Initially, the definition only encompassed national, ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic aspects, without mentioning people with disabilities, women, the LGBT population, among others. However, the use of the term has been expanded over the decades and, more recently, minorities have been considered as marginalized groups by society and, consequently, more vulnerable to discrimination39.

From this perspective, Anita reflected on the behavior of students in the tutorial group, during a module in which they studied social minorities: “[...] you (students) must have a different attitude in our presence, right [...] then there must be lot of discrimination [...] out of our sight, because I imagine they aren’t that wonderful all the time, right?”.

The tutor considered that the behavior that students disclose in the presence of tutors in an academic environment may be different from their behavior outside this context and, consequently, several situations of discrimination might not be visible and may not be perceived by the tutors. The tutoring environment can constrain spontaneity and induce several students to behave as recommended by the learning methodology, that is, showing collaboration and respect for the other, but aiming to be well evaluated by the tutor. It would be very important for these behaviors to be identified and conducted in the best possible way, aiming to build the HR culture at HEIs4.

Subcategory 3.1: Race and Ethnicity

Brazil is a multicultural country and its origin lies in the coexistence of three races: black, white and indigenous40. Historically, since the existence of black slavery in Brazil, society has created and ideologically legitimized the subjection of black people to white values41. Therefore, racism, negative behavior related to minorities, is still present in the Brazilian society41),(42.

On this topic, Anita reported that, in her experience, the absence of diversity (blacks, indigenous people) in the group prevented the students from experiencing a situation of this type of prejudice: “[...] I don’t think there were any blacks in our group and I think there never were any indigenous people either [...] certainly, if they said they had never suffered any prejudice it would be strange [...]”.

An educational environment lacking racial diversity is an example of the historical marginalization and social and racial segregation that persists in the elitist and conservative culture and structure43.

In another group, in the diversity module, Raquel brought a report by a female student who contrasted with the experience reported by Anita: “[...] there was a black student who complained, who said she suffered prejudice [...]”.

The presence of a black student reporting the existence of prejudice legitimizes the cause that is often neglected, as there are not many central subjects of the topic in elite environments, and this ends up reproducing social and racial segregation41),(43.

Raquel, on the other hand, highlighted the importance of having a space for discussion within the college and gave as an example the activities carried out during the ‘Week of Black Awareness’ developed by the Center for Accessibility and Inclusion (NAI, Núcleo de Acessibilidade e Inclusão) of the HEI: “[...] The college itself stimulates them to think about it, during the Week of Black Awareness, even those posters that were affixed to the... Speaking about the data on the black population, you know, mortality, violent death, everything else, I think it already inspires some of that [...]”.

Since 2008, the need for applying an ethnic/social criterion in teaching environments since basic education has been established by law aiming to fight existing prejudices regarding race/ethnicity in our society44. The feasibility of spaces in educational environments that allow discussions and discourses about race and ethnicities benefit the positive struggle of certain collective identities45.

Subcategory 3.2: persons with disabilities (PwD) and ableism

The expression PwD was chosen to represent people who have some type of disability, whether physical, sensory, mental or intellectual46. This is because disability is not inherent to a type of body that deviates from current standards but arises from the interaction between PwD and the behavioral and environmental obstacles of society, which prevent the full and effective participation of these individuals, as well as equality of access to opportunities47.

Historically, PwD are treated as incapable and their bodies as inferior or incomplete. Within this context, ableism emerged, a term related to the discrimination aimed at people with disabilities48.

Regarding ableism, Maria reported the trajectory of a person with a physical disability as an undergraduate student at FPS. She states that, because FPS is an HEI that defends empathy as an educational tool, the student did not suffer any losses during undergraduate school: “In nutrition, we had a student in a wheelchair [...] and the group she was part of [... ] welcomed her very well […] she went into the residency […] but some groups of students […] are not being friendly at all […]“.

In this sense, when HRE occurs adequately, an ethical, empathetic, critical professional emerges, who works with autonomy. Such values may be born inside the HEI but go beyond the walls of the institution. The HEI must position itself regarding HR in its physical structure, guaranteeing accessibility to all students4),(48.

Subcategory 3.3: Fatphobia

Fatphobia is a neologism used as a form of structured and widespread discrimination in several social contexts against fat people and their bodies. This discrimination generates a stigma that the fat body is the result of sloppiness, laziness or failure, and that their social and professional capabilities would be limited by their body characteristics49.

Based on this assumption, Maria reported a series of episodes of stigmatization of the fat person and fatphobia in the academic environment in the nutrition course. In one of the episodes, the student was asked about her ability in the course and in the job market for being fat.

“[...] one of the students suffered a lot of prejudice [...] because she was overweight, [...] they asked several times [...] how could she be a chubby nutritionist, right? because she went to a bakery close to the institution and bought a doughnut [...] this had an impact on the study group” - Maria

Fatphobia is related to beauty standards that have changed over time and, currently, the body that is seen as beautiful and healthy is a thin and athletic one50. In this context, young women are the most vulnerable to sociocultural patterns, in which the cult of the body is associated with the image of power, beauty and social mobility50. This stigmatization of the fat body makes overweight and obese people the targets of prejudice, which sometimes socially marginalizes them49.

Prejudice against fat and obese people is experienced daily and is identified in many health professionals. The cult of the thin body affects both patients in health services and professionals in the field49.

Category 4: student stigmatization and self-esteem

Subcategory 4.1: mental health and psychophobia

Human rights are considered fundamental rights for everyone, so it is essential to pay attention to factors that prevent individuals with mental health (MH) problems from having all their rights guaranteed. In the educational field, students must have quality learning and psychopedagogical support, if necessary. Among medical students, problems related to mental health have a high prevalence51, which reinforces the need for attention to these students, who still suffer with psychophobia, a term recently used to define prejudice against people who suffer from psychological disorders52.

When the topics of mental health and psychophobia emerged in the FG discussion, Cecília reported that certain situations can lead to a decrease in concentration or difficulty in participating in daily activities, including tutoring, either due to personal problems or the use of medication to treat mental disorders.

“[...] people have triggers, and it is hard for you to say, the person leaves their house fine but arrives at a place and that trigger comes back, and they lose their balance and can’t be well [...] I see these great difficulties of our professionals [...] in education, to understand people who have mental health problems”. - Cecilia

The individuality of the human being makes each student have difficulties and problems that are intrinsic to them53, and support should be given so that these obstacles and difficulties are overcome with the least possible impact, both educationally and in their personal life. This support must be provided both by tutors and by the coordination of courses for the adequate referral of cases, so that there is no academic harm to students54.

FPS has a psycho-pedagogical sector that seeks to meet the demands of the student body, through measures such as: integration and diagnosis of new students, comprehending pedagogical, affective and social fields; carrying out individual consultations at the HEI; referral of students to psychotherapeutic care if the need is identified; holding thematic workshops55.

Regarding the difficulties faced in the tutorial environment, possibly due to mental health problems, Raquel reported that a student was kept away by the group for having a more introspective and quiet behavior: “A male student who was very quiet, I think he had depression, some anxiety, he was missing a lot of classes [...] the students kind of snubbed him, on the day he did not come, “ah, that weird boy, what’s his name?”.

Psychophobia and rejection of what is different are intrinsic problems in today’s society30 and can be observed in the tutor’s report. If these problems are carried over to the tutoring, there is a risk of harming the group’s learning, given that the success of the tutorial group depends on a collaborative interaction between peers; it is up to the tutor to know how to guide and coordinate the group, in order to guarantee the learning, in addition to encouraging the group to integrate the student who suffers from mental health problems56.

Subcategory 4.2: interpersonal conflicts

Within an active methodology such as PBL, in which students need to collaborate and interact in small groups, it is common for conflicts to arise between students, whether due to disagreements on the addressed topic or personal differences. Without the correct conduct, such conflicts can harm learning, as tutoring discussions should encourage students to build knowledge in a self-directed and collaborative way57.

Freire reported a discussion between classmates, which he believes were due to “profound disrespect” between two female students, and how he proceeded in the face of the conflict:

“[...] And during the reading, one said in a loud enough voice [...] “what a boring girl”, and then the one who was reading, interrupted her reading and said “YOU are the boring one [...] even words of intimidation, one to the other [...] in the end, I gave an individual opinion with both of them, then I gave the homogeneous feedback to the group... I said, I will listen more, talk less, talk to the tutorial coordinator and understand it” - Freire

The tutor’s role as a mediator in a conflict situation in the tutorial group is fundamental, to maintain the group balance and functionality without compromising the learning process. Some skills are essential for the tutor when conducting a tutorial group, such as, for instance, creating an environment that allows the free flow of ideas, ensuring the harmonious participation of all8),(56, in addition to feedback, which offers students an opportunity to review and improve their behavior58.

There is a tutor support flow at the HEI, in which, after the conclusion of each tutorial group, a meeting is held in which all the tutors of that module and class participate with their tutor coordinator and, in this space, the difficulties experienced in the tutorial group are discussed. The identified problems, if necessary, are forwarded to the Structuring Teaching Center (NDE, Núcleo Docente Estruturante) and the Teaching Development Committee (CDD, Comitê de Desenvolvimento Docente).

Finally, from the experiences reported by the tutors involving issues related to HR in the tutorial group environment, it was observed that, in general, they were insecure to intervene in these situations, especially when they generated conflict between the students. They reported having little information on the subject and also expressed difficulties in providing both individual and collective feedback in these cases.

Feedback is an important learning tool, because through the suggestions that are provided, it offers the recipient the opportunity to change certain aspects of their behavior. It is most effective if it is targeted, explicit, functional, and immediately related to the observed behavior. It should be given at the appropriate time, as soon as possible after the observation, and the recipient should be given the opportunity to answer to it59)-(61.

The feedback session is an opportunity for interaction between tutor and students, aiming at reflection and performance improvement. This moment should not be understood as an evaluation, comparison or personal judgment, but a neutral, objective and specific description of behaviors and attitudes that can be improved59)-(61.

Based on these assertions, the importance of preparing the tutor for the exercise of their function and for them to be able to give feedback to the students and receive it from them is inferred. It is worth emphasizing that before joining the FPS and before starting their work, all tutors go through the PBL tutor training course and receive regular training to provide feedback in tutorial groups, both individually and collectively. Everyone must go through a new training every five years. The importance of working in teacher development is highlighted, which should not be restricted to courses that are intermittently offered, but above all, in the management of day-to-day processes.

The institution has tutor coordinators, one coordinator for every seven tutors, whose main function is to provide support and subsidies to the tutor so they can adequately perform their role, especially in the group facilitating processes. Within this dynamic, feedbacks are carried out with the tutors at least every six months. Moreover, there are several instruments prepared by the Faculty Development Committee, which meet all validation steps of measurement instruments, for regular evaluation of the learning processes. In relation to the tutor, the Short Tutor Evaluation Questionnaire is used, translated and cross-culturally adapted62, which evaluates the tutor in relation to the fundamental educational principles of PBL, reflected in the types of collaborative, constructive, contextual and self-directed learning.9),(63),(64

However, training so far has prioritized aspects related to the PBL learning methodology. When tutors report not knowing and not looking for documents that correlate HR to education and disclose that, although they thought it was relevant, they had never looked for these documents, unfortunately, it was verified that information and learning about HR still do not have much space in the academic environment. As a result, the need for greater comprehensiveness in teacher training is reinforced, especially regarding this topic, as one of the steps for the implementation of the HR culture in the HEI and for greater effectiveness in learning and professional training.

CONCLUSION

Considering the experiences involving issues related to HD in the academic environment, the tutors reported episodes that deal with aspects of gender and sexuality, difficulties in communication and freedom of expression, social minorities and student stigmatization and self-esteem. Overall, it is understood that they felt insecure to intervene in these situations, especially when they generated conflict between students. They reported having little information about HR and expressed difficulties in providing both individual and collective feedback in these cases. Therefore, aiming at implementing teacher development, the HEI, through the CDD, is responsible for providing training tools to the tutor. One example is the implementation of a course on HRE aimed at this population.

texto em

texto em