Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versão impressa ISSN 0100-5502versão On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.46 no.3 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 19-Out-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v46.3-20210392

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ABEM consensus for the brazilian medical schools’ communication curriculum

1Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

2Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil.

3Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Chapecó, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

4Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

5Universidade João do Rosário Vellano, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

6Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil.

7Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, Petrolina, Pernambuco, Brazil.

8Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

9Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

10Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

11Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil.

12Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil.

13Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

14Faculdades Pequeno Príncipe, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil.

Introduction:

Communication is an essential competence for the physician and other professional categories, and must be developed their professional training. The creation of a communication project including a Brazilian consensus aimed to subsidize medical schools in preparing medical students to communicate effectively with Brazilian citizens, with plural intra and inter-regional characteristics, based on the professionalism and the Brazilian Unified System (SUS) principles.

Objective:

The objective of this manuscript is to present the consensus for the teaching of communication in Brazilian medical schools.

Method:

The consensus was built collaboratively with 276 participants, experts in communication, faculty, health professionals and students from 126 medical schools and five health institutions in face-to-face conference meetings and biweekly or monthly virtual meetings. In the meetings, the participants’ experiences and bibliographic material were shared, including international consensuses, and the consensus under construction was presented, with group discussion to list new components for the Brazilian consensus, followed by debate with everyone, to agree on them. The final version was approved in a virtual meeting with invitation to all participants in July 2021. After the submission, several changes were required, which demanded new meetings to review the consensus final version.

Result:

The consensus is based on assumptions that communication should be relationship-centered, embedded on professionalism, grounded on the SUS principles and social participation, and based on the National Guidelines for the undergraduate medical course, theoretical references and scientific evidence. Specific objectives to develop communication competence in the students are described, covering: theoretical foundations; literature search and its critical evaluation; documents drafting and editing; intrapersonal and interpersonal communication in the academicscientific environment, in health care and in health management; and, communication in diverse clinical contexts. The inclusion of communication in the curriculum is recommended from the beginning to the end of the course, integrated with other contents and areas of knowledge.

Conclusion:

It is expected that this consensus contributes the review or implementation of communication in Brazilian medical schools’ curricula.

Keywords: Communication; Medical Schools; Curriculum; Undergraduate Medical Education; Consensus

Introdução:

A comunicação é uma competência essencial para o(a) médico(a) e outras categorias profissionais, e deve ser desenvolvida durante sua formação profissional. A elaboração de um projeto de comunicação, incluindo um consenso brasileiro, visou subsidiar as escolas médicas a preparar os estudantes de Medicina para se comunicarem efetivamente com os(as) cidadãos/cidadãs brasileiros(as), de características plurais intra e inter-regionais, pautando-se no profissionalismo e nos princípios do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS).

Objetivo:

Este manuscrito apresenta o consenso para o ensino de comunicação nas escolas médicas brasileiras.

Método:

O consenso foi construído colaborativamente com 276 participantes, experts em comunicação, docentes, profissionais de saúde e discentes, de 126 escolas médicas e cinco instituições de saúde, ao longo de nove encontros presenciais em congressos e de encontros virtuais quinzenais ou mensais. Nos encontros, compartilharam-se as experiências dos participantes e o material bibliográfico, incluindo os consensos internacionais, e apresentou-se o consenso em construção, com discussão em grupos para elencar novos componentes para o consenso brasileiro, seguida por debate com todos para pactuá-los. A versão final foi aprovada em reunião virtual, com convite a todos(as) os(as) participantes em julho de 2021. Após submissão, diversas alterações foram requeridas, o que demandou novos encontros para revisão da versão final do consenso.

Resultado:

O consenso tem como pressupostos que a comunicação deve ser centrada nas relações, pautada nos princípios do SUS, na participação social e no profissionalismo, e embasada nas Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do curso de graduação em Medicina, em referenciais teóricos e nas evidências científicas. São descritos objetivos específicos para desenvolver a competência em comunicação nos estudantes, abrangendo: fundamentos teóricos; busca e avaliação crítica da literatura; elaboração e redação de documentos; comunicação intrapessoal e interpessoal no ambiente acadêmico-científico, na atenção à saúde em diversos contextos clínicos e na gestão em saúde. Recomenda-se a inserção curricular da comunicação do início ao final do curso, integrada a outros conteúdos e áreas de saber.

Conclusão:

Espera-se que esse consenso contribua para a revisão ou implementação da comunicação nos currículos das escolas médicas brasileiras.

Palavras-chave: Comunicação; Escolas Médicas; Currículo; Educação de Graduação em Medicina; Consenso

INTRODUCTION

The word “communicate” derives from the Latin word communicare and means to share, to make public, to relate to, from which the word “commune” also originated, which means to share with everyone, to participate, to do something in common, to tune into feelings, thoughts and actions1. Thus, communication is relational and, as Araújo and Cardoso state, it is a “social practice”2. For Paulo Freire, communication is an essential condition of human beings, and without it, human knowledge would be impossible, as the cultural and historical construction of human reality requires “intercommunication” and “intersubjectivity” based on dialogicity3. Therefore, the educator, who aims to expand the perspectives and possibilities for the student’s assertion as a person in the society, through reflection and action on reality, must problematize the world, in a dialogic and solidary way3),(4.

Therefore, the importance of dialogue should always be taken into account by educators/teachers of the medical course and physicians. In the past, however, teaching was teacher-centered and the clinical encounter was physician-centered and based on the biomedical model, focused on the disease, limiting the active participation of the students and those under medical care. In the teaching process, in clinical reasoning and in decision making, their knowledge, experiences, perspectives and practices, as well as their values, were not taken into account5),(6.

In health care, this reality started to change in the 1970s, when studies demonstrated that the biopsychosocial model7, encouraging the active participation of the person under care and attentive listening and empathy8 generated better health outcomes. Some proven outcomes were: decrease of uncertainties in people under care and increase in their trust, security, adherence to the therapeutic plan, autonomy and responsibility for self-care, as well as better control of chronic diseases, including hypertension and diabetes and less stress, anxiety and depression. Family members also felt less anxious and stressed, and physicians achieved greater diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness in their care. As a result, everyone was more satisfied9)-(17.

The importance of communication in interdisciplinary and interprofessional teamwork was also verified - considering the person under care and their family members / caregivers as part of the team - for the prevention of avoidable harm in health care and, therefore, to ensure the safety of the person under care18)-(25. It was demonstrated that the greater effectiveness of collaborative work required a shared leadership, respect for all involved, with their listening, recognition and appreciation of their contribution to the team’s mission, and through frequent, assertive and conciliatory dialogue, would provide the fast and effective flow of information, the construction and maintenance of relations, clarity of roles and functions of each participant and the management of uncertainties, conflicts, adverse events and errors18)-(27. As a result, the person under care accepts the treatment better, has better health outcomes, takes less risks and feels more satisfied; team members work more effectively and feel greater well-being; and, there is greater efficiency in the services provided by the team and access to care, and the hospital length of stay, unplanned hospitalizations and institutional costs are reduced18)-(27.

On the other hand, it was found that when communication in teamwork was ineffective, there were more errors in health care, including delays in diagnosis and treatment and an increase in medication and procedural errors19)-(22. Their most frequent causes were the omission of important clinical information, verbal prescription, illegible writing in medical records and files and/or the absence of the name, signature and stamp/digital certification of the professional responsible for the care. These problems occurred more frequently during the transition of care between shifts, in transfers between sectors and between health institutions, and in emergency situations. Proven barriers to communication in teamwork include hierarchy, little regard for the opinion of its members, failure to include the person under care and their family members/caregivers as part of the team, and little clarity about the role and functions of the team member, which are corroborated by the instability of the teams and/or transitoriness of its members and the assignment of tasks to new members, without support and prior qualification, among others18)-(25.

As for the qualification for teamwork, a recent systematic review of the resources in the literature on communication for health professionals during the Covid-19 pandemic concluded that most articles and documents were directed at the physicians, and there was a gap related to the resources for non-medical professionals. Topics that required greater consideration, indicated by the authors, included: communication strategies in telehealth, cultural sensitivity, empathy, compassion, loss, grief and moral distress28 caused by the witnessing of inappropriate attitudes and actions or the need to make decisions that go against one’s own moral values, often due to the scarcity of resources29.

The importance of training health professionals for the 21st century, so they can effectively communicate in collaborative interdisciplinary/interprofessional, intersectoral and transnational teamwork, in health leadership and in local, regional, national and global politics has been highlighted. This competence is necessary so that teams can act in a responsive way to the constant changes in local, national and global health needs, favoring the transformation of reality (transformational education), and to improve “health systems in an interdependent world”, promoting the health of populations, universal equity in health, social justice, global socioeconomic development and human security30. In this context, human health must be understood as part of a web of interdependent relationships with life in a broader sense, dependent on the consolidation of relationships of solidarity and individual, collective and environmental care31, without territorial boundaries. As stated in the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN, Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais) for the undergraduate medical course, health care must preserve “biodiversity with sustainability”, respecting the relationships between “human beings, the environment, society and technologies”32.

Since the 1990s, the model of care centered on relationships has emerged33, recognizing that, in addition to the relationship with the person under care, all the relationships created at each moment and in each space of health care influence each other and that care is interdependent on these relationships. This means that each person involved in this care influences its results, bringing to this encounter their subjectivity, with a personality and life story and their relationships with themselves, their emotions, interpretations, perspectives, needs, expectations and choices, and their own knowledge and values. Thus, the physician must be aware of how they, their emotions and all of their subjectivity, as well as those of other people involved in care, contribute to the care outcomes33)-(36.

The knowledge built on effective communication processes and components and on the effectiveness of their teaching37 contributed to the development of models to construct the clinical encounter and, among them, the method centered on the person under care38, the SEGUE (Set the stage, Elicit information, Give information, Understand the patient’s perspective, and End the encounter) method39, the Calgary-Cambridge guide40,41 and the Four Habits Model42. Moreover, consensuses were created for the teaching of communication in undergraduate medical courses43)-(52. As professionalism is a construct, whose components are essential to medical practice52)-(56 (as well as to the practice of other professional categories), it is one of the bases of communication in some consensuses, such as in the ones from the United Kingdom46),(51. The security of the person under care, while part of professionalism, is another basis of communication in the most recent UK consensus51.

Several books have also been published to support the teaching of medical communication in general and in the clinical encounter. Some of them are mentioned here to provide greater familiarity to those interested in the topic2),(38),(57)-(62, but they are just the “tip of the iceberg” amidst the existing vastness.

The international consensuses for the teaching of communication partially meet the needs of medical training in Brazil, considering that its population exceeds 200 million inhabitants, which has different intra and inter-regional characteristics and needs63, and that its public health system - the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde) - has as principles the universality (egalitarian access to health services for all individuals64),(65), integrality (integral vision of the human being, with comprehensive and effective actions in health64),(65) and equity (respect for the uniqueness and subjectivity of each person, considering their individual and collective characteristics and needs, without any kind of prejudice or privilege, prioritizing vulnerable and at-risk groups or categories, to defend dignified treatment and guarantee social justice64),(65). The SUS also includes the social control guideline, which presupposes the active and daily participation of the population in discussions to direct health services and actions in all of their instances, so that the system meets their needs and interests 64. Embracement, which includes listening to the users of the Unified Health System (SUS) and other Brazilian citizens, is part of the national humanization policy to increase social participation and meet the health needs of the population64),(66.

The DCNs, introduced in 2001, aimed to align medical education with the learning needs of the students and with the health needs of the population according to the SUS. In the DCNs, communication was one of the six skills to be achieved by medical school graduates67. After the “More Doctors Program” (PMM, Programa Mais Médicos) in 201368, the guidelines were revised, resulting in the 2014 version of the DCNs32. The previous focus on six competencies to be achieved changed to competencies in relation to the areas of health care, health management and health education. Communication permeates most processes in these three areas of competence.

Being aware of the importance of training Brazilian physicians to effectively communicate when attending to the Brazilian population, while following the principles of the SUS, ABEM developed a communication project, containing among its objectives the construction of a consensus for its teaching in Brazilian medical courses69),(70. The aim of this manuscript is to present the consensus for the teaching of communication in Brazilian medical schools.

METHOD

The creation of the consensus started in 201469. Its construction was carried out in a collective and collaborative manner. According to Innes and Booher71 and Innes72, a collaboratively constructed consensus constitutes “a set of practices” in which people representing different interests meet for a long-term dialogue, mediated by a facilitator, to address an issue or concern and arrive at a joint proposal. Its construction process must contain the following criteria: include representatives with different levels of interest; be guided by goals, tasks and practices shared by the group; allow participants to actively interact throughout the process, encouraging creative thinking; incorporate high quality information and evidence; reach an agreement on their meanings; and seek consensus by agreement, after broadly exploring the answers to the differences, through discussions65)-(66.

To ensure the participation of as many representatives as possible and their diversity, the discussions took place in person between 2014 and 2018 in six workshops held at the Brazilian Congresses of Medical Education promoted by ABEM, and three specific events on communication. The total number of participants was 276, including communication experts and teachers, students and other professionals interested in the area, from 126 higher education institutions in the medical and health area, four Health Secretariats and one Health foundation. One group met virtually, every two weeks or monthly, after the first in-person workshop.

Each in-person meeting lasted from four to eight hours and its dynamic consisted of sharing experiences in the teaching of communication and bibliographic material brought by experts, in addition to international consensuses, as they were being published40)-(50 and the presentation of the version under construction of the Brazilian consensus offered by the organizers. New knowledge, skills and attitudes that should be part of the consensus were then discussed in small groups, which were subsequently presented to all the participants, with debates and agreement on the content to remain, confirmed by voting. As several components of professionalism were listed in the construction process, one of the workshops was aimed to discuss which components should be included in the consensus. The decision was unanimous to keep all of them and to consider professionalism as one of the bases of communication. The virtual meetings followed the same dynamics as the in-person meetings but lasted from one and a half to two hours.

The consensus was finalized in 2020 by the virtual group. However, the new communication challenges highlighted throughout the Covid-1973 pandemic required its review.

The semifinal version of the consensus was presented in July 2021 at a meeting held on ABEM’s virtual platform, with an invitation being sent to its directors and all those who had participated at some point in its construction process, when changes were suggested to be included in its final version, which was unanimously approved. After being submitted to the present journal, one of the opinions demanded new virtual meetings to consider the listed recommendations. The new final version was approved in a virtual meeting with an invitation being sent to all the participants of the consensus at the end of February 2022.

Considering the importance of the material shared by the participants throughout the consensus construction process and also the lack of familiarity that some readers might have in relation to some of the mentioned aspects, unlike other consensuses, this one contains bibliographic references in some of its specific objectives. We would like to clarify that articles and books cited as references were selected according to their relevance, aiming to support educators in the teaching of communication; however, without the intention of exhausting the literature. The explanation of some concepts and terms are also provided in a separate table, to facilitate their understanding by readers who may not know them.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: THE CONSENSUS

The teaching of communication in medical schools should have the overall objective of developing knowledge, skills and attitudes in the medical student, so that, when they graduate from the course, they can demonstrate competence when communicating with the people involved in the academic-scientific environment, in health care and health management.

The people involved include students, faculty, physicians, professionals in the healthcare area and other areas of knowledge, members of the interdisciplinary and interprofessional team, employees, researchers, managers, people under care, their family members, caregivers, guardians, loved ones, interpreters, people who respond for them, families, social groups, the community and its representatives and other people with whom the physician has a relationship in their professional performance.

Communication must be based on relationships, being grounded on professionalism, on the principles of the SUS and on social participation. Medical training must be guided by the DCNs and be based on theoretical references and scientific evidence. The DCNs establish that the medical course must provide a “humanistic, critical, reflective and ethical” training, and that it should develop in the student the

Capacity to act at the different levels of health care, with actions to promote, prevent, recover and rehabilitate health at the individual and collective levels, with social responsibility and commitment to the defense of citizenship, human dignity, the integral health of the human being and having as transversality in its practice, always, the social determination of the health and disease process32.

The DCNs also establish that, in health care, the student must be trained to act, considering “always the biological, subjective, ethnic-racial, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic, political, environmental, cultural, and ethical dimensions, and other aspects that comprise the spectrum of human diversity that make each person or each social group unique”32, which is in line with the principles and guidelines of SUS64 and constitutes one of the components of professionalism52)-(56, which includes:

1. Bioethics and Ethics, which involve

1.1. Respect for

1.1.1. human dignity and freedom of individual and social choice, considering the uniqueness of each person or social group, in the cultural, ethnic-racial, spiritual, socioeconomic and environmental plurality, as well as of gender and sexual orientation and choices, values, beliefs, perspectives and preferences;

1.1.2. the privacy and modesty of the person under care;

1.1.3. the autonomy of the person under care and responsibility for its promotion;

1.2. Subordination of self-interest in favor of the interests of people under one’s care and of their family members / caregivers;

1.3. Recognition of professional limitations,

1.4. Secrecy and confidentiality;

1.5. Responsibility for the safety and comfort of the person under care.

2. Honesty, probity and integrity;

3. Demonstration of humanistic values, such as altruism, empathy, compassion, solidarity, sensitivity, understanding, interest and affection;

4. Accountability in fulfilling the professional contract, with responsibility, responsiveness, reliability in actions and legal subordination to obligations;

5. Social responsibility, being committed to the defense of citizenship, human dignity, and the integral health of the human being;

6. Commitment to excellence, academic and professional merit, as well as lifelong learning;

7. Effective communication:

7.1. intrapersonal: self-awareness (presence, recognition and management of one’s own emotions and self-care), reflective practice, critical thinking and adaptability (acknowledgement of limitations and seeking help, acceptance and provision of constructive feedback, resilience, flexibility to transform knowledge and one’s own practice and dealing with high levels of complexity and uncertainty);

7.2. interpersonal (detailed in the consensus).

In the medical course curriculum, communication must be included from the beginning of the course and continue until its end. The contents must have increasing complexity and be appropriately integrated with other contents, having the “Human and Social Sciences as a transversal axis” and the inclusion of “transversal topics [...] that involve [...] “human rights” and [...] public policies, programs, strategic actions and current national and international guidelines for education and health”32.

The interaction “of the student with health users and professionals” must occur throughout the course and interprofessional learning and interdisciplinarity must be provided, integrating the “biological, psychological, ethnic-racial, socioeconomic, cultural, environmental and educational dimensions” in the different scenarios of teaching, extension and research, which are inseparable32.

The pedagogical approach must contain varied and interactive strategies that encourage student participation in the construction of their knowledge, associate theory with practice, stimulate curiosity, creativity, reflective practice, critical thinking and sensitivity, including, whenever possible, the humanities32),(59)-(62.

Practices should aim to incorporate knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSAs) with increasing complexity and have appreciation feedback for their improvement. The practical learning environment should be more controlled initially, such as, for instance, with role-playing or simulation in a communication laboratory, and progress to a less controlled environment, such as real-life scenarios, under supervision59)-(62.

The assessment should be predominantly formative, without disregarding summative assessments59)-(62.

The educational environment must be a safe one and cultivate ethics, sensitivity, empathy, solidarity, affection74 and non-violent75, inclusive and non-prejudiced communication, which makes medical training a model “from” and “for” the care that enhance the medical student’s ability to establish respectful and constructive relationships in their process of learning and caring for themselves and others.

For this purpose, the institution must include the daily embracement of the student and the educator, listening to them and valuing their emotions, and it must contain structures for their psychological and pedagogical support. The problematization and critical reflection76 of the socialization process must be carried out in a systematic and planned manner, for the development of the medical professional identity construction and the best use of the teaching-learning process, aiming at attaining the objectives of the undergraduate medical course, which is to train competent, ethical, critical, solidary physicians, with social responsibility and committed to the defense of human dignity and social justice32.

The hidden curriculum, characterized by witnessed attitudes and shared messages that are negative, ambiguous and not consistent with the objectives pursued by the course77, must be the object of regular problematization and reflection in the formal curriculum. Based on praxis (reflection on practice), strategies must be developed to build a non-oppressive environment that encourages healthy relationships78.

According to Bakhtin, we build ourselves in the interaction with other people79, being the word the most pure and sensible form of the social relation and the communication the dynamic process for building social meanings. Language carries an ideology and a practice, and each “speech, statement or text expresses a multiplicity of voices, most of them without the speaker being aware of it”2),(79),(80, which represent different interests and positions in the social structure. As what people “are or will become depends on a continuum of ruptures and transformations that occur as we interact with others”2),(79, disrespectful messages run the risk of being legitimized and incorporated by the student of medicine, especially when they are shared in a subtle manner81, with derogatory gestures, jokes, images or comments. These strategies allow their disrespectful and unethical content to go unnoticed.

It is crucial that students and educators understand the ideologies that underlie the discourses about “the other”, and that the hegemonic discourse in a given society is historically constructed through struggles, being socially shared in its different institutions (e.g., family and religious and educational institutions, which includes the medical school). It contains arbitrary criteria of classification, stratification and normativity regarding superiority/inferiority and inclusion/exclusion, which serve specific interests of power, privileges and/or prestige82),(83. The non-perception of this arbitrariness is what makes them legitimate and perpetuated as common sense, generating multiple prejudiced interpretations such as classism, racism, sexism, machismo, capacitism, LGBTQIA+phobia and xenophobia82)-(84, and other authoritarian and oppressive attitudes, of discrimination and intolerance. Based on the reflection, it is expected that people involved in the academic environment will increase their awareness of the values of professionalism to be cultivated.

To ensure the implementation and quality of communication teaching in medical schools, it is essential to encourage and support faculty development for the teaching of communication in institutional programs or in existing programs outside the institutions.

According to the DCNs, in its single paragraph of chapter II:

[…] competence is understood as the ability to mobilize knowledges, skills and attitudes, using the available resources, and expressing itself as initiatives and actions that will translate into performances capable of solving, with relevance, opportunity and success, the challenges that arise in professional practice, in different contexts of health work, translated into the excellence of medical practice, primarily in the scenarios of the Unified Health System (SUS).

Therefore, we describe the KSAs to be developed throughout the course, described as specific objectives in Table 1. In it, the excerpts written between quotation marks are citations from the DCNs32. For certain specific purposes, relevant references are cited, which can help educators in the teaching of communication and physicians in their practice. For example, the “World Health Organization Patient Safety Curriculum Guide”19, quoted several times, addresses: characteristics of effective communication; cultural competence; teamwork communication; safety of the person under care; conflict management; error management and disclosure; management of uncertainties; and, communicating difficult news, among other topics; and contains roadmaps for the safety of the person under care in procedures, emergencies, changes in work shifts, transfer between sectors and between institutions and for other communication topics, as well as documents, including informed consent and the form for the reporting of adverse events and errors.

Table 1 Specific communication objectives to be developed throughout the medical course in Brazilian medical schools

| To develop competence in communication, throughout the medical course, the student must: |

|---|

Become capable of communicating based on theoretical foundations, including

|

Search, critically evaluate the literature and prepare and write documents adequately, becoming able to

|

Develop as a person (intrapersonal communication), with improvement of self-knowledge, adaptability, critical reflection and critical thinking, becoming capable of

|

Improve interpersonal communication, becoming able to

|

Additionally, in health care, the student must become able to

|

Additionally, in health management, the student must become able to

|

Source: the authors

We emphasize again, however, that the cited references are just a few among the vastness of the existing literature on communication.

Table 2 provides some concepts and explanations of terms covered in this manuscript, to facilitate the readers' understanding.

Table 2 Explanations and details of some terms used in the manuscript

| Term | Detailing |

|---|---|

| Assertiveness | Ability to share thoughts, perspectives, feelings and emotions in a respectful, calm, direct and sincere manner, defending personal and other people’s rights, even asking for a change in behavior when perceiving the risks for them, with arguments based on facts and not on personal characteristics and without making value judgments, embarrassing, offending, humiliating or violating the rights of other people, remaining open and flexible to listen to everyone and sensitive to their feelings, dealing with one’s own emotions and maintaining self-control19),(26),(27 |

| External barriers to communication and intrapersonal limitations to communicating | Barriers that can be located in the physical environment, which include computer and sounds of appliances and equipment, among others; they can occur due to the use of protective equipment, which prevent the total or partial visualization of the meeting participants. They may result from the use of the virtual environment, with difficulty in access, internet instability, loss of visualization of the participants and impossibility of in-person approach. The limitations include: lack of mastery of the language spoken by the physician or by the person under care and caregivers, without the mediation of interpreters; early stage of neuropsychomotor development, with consequent lack of native language repertoire and social skills, as in the case of children; alterations in the neurological development, resulting in cognitive impairment and global developmental disorders, which also impair social interactions (such as autism spectrum disorders); auditory sensory alteration not mediated by an interpreter; visual sensory alteration that prevents the reading of documents such as the prescription; diseases of neurological, neuromuscular or oncological origin that cause dysphasia, aphasia, cognitive impairment or limitation of motor movement responsible for speech, including stroke, brain injuries, dementia, locked-in syndrome, head and neck cancer, Parkinson’s disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, among others; and, situations that generate the transient impossibility of speaking, such as ventilatory support and tracheostomy, among others; psychiatric disorders and alterations in mental status due to intoxication by psychoactive substances |

| Alternative and augmentative Communication (CAA) | Diversity of linguistic resources (communication systems) with the aim of mediating, supplementing and/or facilitating interactions between people with impaired oral, gestural and/or written communication, of physical, mental, intellectual or sensory origin. It allows the person’s social participation and the sharing of their emotions, perspectives and desires. It tends to improve motor, cognitive and affective development with improved self-esteem, self-confidence and empathy. Extended communication complements the existing speech, and its users have difficulties in speaking and understanding language. In the alternative communication, speech is non-existent or non-functional and its users have a cognitive understanding of language, but have difficulty speaking, and it can be permanent or temporary due to interventions such as intubation and tracheostomy. CAA can be non-assistive (unsupported), when only the human body is used to communicate, or assistive, when it depends on resources that are external to the body. Resources with no or low technology include communication by written and sign language, by gestures, facial expressions, alphabet boards or pictographic symbols, among others. High-tech resources include mobile devices, voice communicators, computers, tablets and software with programmable functions, which convert text into natural sounds and symbols, according to the user’s needs. They use a variety of methods to detect human signals generated by body movements, such as image sensors activated by eye tracking and head signals, mechanical and electromechanical sensors activated by mechanical boards and switch access to use the computer screen, touch-activated sensors such as touchscreens, breath-activated sensors by microphones and low-pressure sensors, and sensors with invasive or non-invasive brain-computer interface94)-(98. |

| Support systems for people with expressive or receptive communication disorders | Support systems for people with expressive or receptive communication disorders include expanded additional support, and assistive hearing technology systems. They include Braille, hearing amplification through hearing aids, cochlear implants and assistive hearing technology systems (such as personal amplification devices via text telephones and telecommunication devices for the deaf); and, artificial phonation devices and voice amplifiers, such as intraoral devices and valves for speech (as used in people with tracheostomy, for instance)97. |

| Non-violent communication | It aims at maintaining peaceful everyday interactions, cultivating self-awareness and self-compassion, and honoring one’s own needs and values and the needs and values of others. Its process includes observing and listening attentively to others without judgment, reflection to identify one’s feelings in relation to what is observed and the recognition of the personal needs, values and desires that generate these feelings, confirmation of the understanding about what the other person speaks, paraphrasing to check for accuracy, using specific words to express feelings and emotions rather than unclear words, making requests clearly and specifically without demanding their fulfillment, being empathetic, understanding, and compassionate when they are refused, respecting the person’s choice to do something or comply with our request of their own free will75. |

| Pragmatic communication | Ability to use language in context and to understand and express the basic meanings of words (semantics) with correct grammatical forms (syntax). Its characteristics include providing information that is appropriate to the needs of those who receive it, expressing perspectives and ideas in a logical and coherent sequence, sharing problems and monitoring the adequacy of the production of one’s own speech in a specific context, among others92),(93. |

| Verbal and non-verbal communication | Verbal communication expresses the word, either orally or in written/typed form. Non-verbal communication encompasses all other forms of communication that do not represent the word, but influence its interpretation, such as paralanguage (tone, intensity, rhythm, volume and sounds that are not words like “Uh huh”), kinesics (body movements, including gestures, posture, head movements, facial expressions, way of looking, among others) and proxemics (how people perceive and use interpersonal space), among others60),(61),(89),(90. |

| Disaster | Serious disturbance in the function of a community or society, due to the interaction between hazardous events and conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, which results in human, material, economic and/or environmental losses and impacts. It can have a natural origin (meteorological and hydrological, extraterrestrial and/or geological), biological (such as epidemics and pandemics) and/or anthropogenic (technological, chemical, social and environmental). It is currently considered that all disasters are mixed, due to the interdependence between these phenomena110),(111. |

| Social skills | Specific behaviors in specific contexts in a given social environment, to interrelate and complete social tasks. The main classes of social skills include: communication, civility, making and maintaining friendships, empathy, assertive skills, expressing solidarity, managing conflicts and resolving interpersonal problems, expressing affection and intimacy, coordinating groups, and public speaking88. |

| Emotional Intelligence | Ability to understand oneself, including one’s own emotions, fears, feelings and motivations, and to understand other people’s emotions, motivations and expectations, which can be categorized into five domains: emotional self-knowledge, emotional control, self-motivation, recognition of emotions in other people and social skills for interpersonal relationships. The last two are crucial for group organization and leadership, conflict management and solution agreement, empathy and social sensitivity87. |

| Idiom | System of codes with rules that allow the communication between certain social groups1. |

| Language | According to the Houaiss1 dictionary, on page 1763: “1. Any systematic means of communicating ideas or feelings through conventional signs, sound, graphics, gestures, etc. [...]”. |

| Metadiscourse | Discourse function through the analysis of how signs are designed to influence meanings and attitudes85),(86. |

| Operational levels of verbal communication | They include three levels. One of them is concrete, which is the denotative level, related to the content. Two of them are more subjective; the metalinguistic one, related to the type of language used, and metacommunication one, related to the interpretation of the received messages, mainly through implicit messages of non-verbal signals, but also, more rarely, by explicit verbal ones86),(91. |

| Information and communication technologies (ICT) | Set of integrated technological resources to process information and assist in communication. They cover all forms of transmission of information and technologies that interfere and intervene in information and communication processes between human beings. It can be performed through computers, tablets, cell phones, software and telecommunications. The exchange of information can occur in a virtual synchronous way, with tools such as, for example, telephones, virtual platforms, WhatsApp and other applications; and, asynchronously, with tools such as e-mail messages, text messaging applications such as SMS, virtual platforms, websites, television, radio, among others. Their use in health care includes several activities, including, but not limited to, videoconferences, consultations, virtual procedures, filling out medical records and electronic forms, sharing of messages, exams, data and other documents. |

Figure 1 illustrates the different stages and processes of the relationship-centered encounter.

Figure 1 Communication centered on relationships in the different stages and processes of the clinical encountera

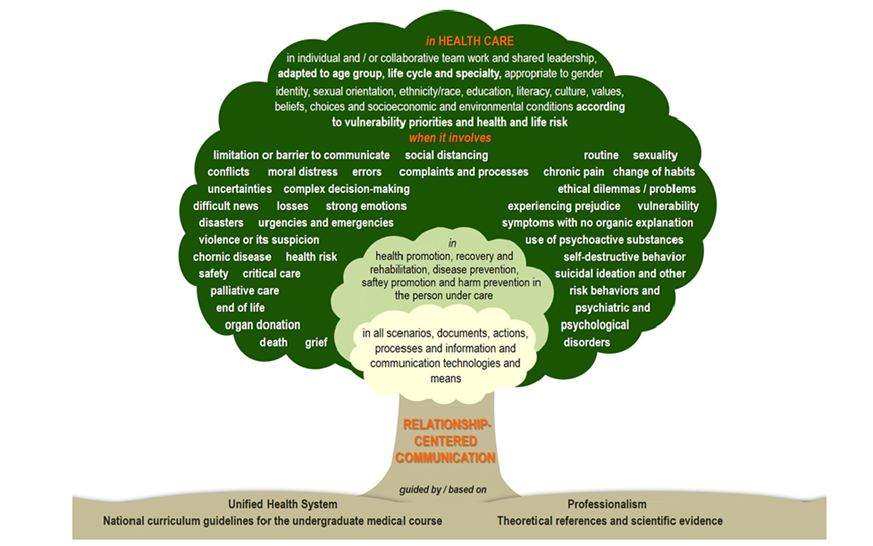

Figure 2 illustrates specific contexts in which the medical student must acquire the ability to communicate in health care, represented by a tree. Its trunk represents communication centered on relationships, its base represents its support by professionalism52)-(56, the SUS64, the DCNs32 and theoretical references and scientific evidence, by which it must be guided or on which it must be grounded, and its canopy cover contains the contexts for the teaching of communication in health care.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This is the first consensus for the teaching of communication in Brazilian medical schools. We emphasize, however, that it represents an initial step and that, due to its collective and collaborative construction with representatives from more than half of the medical schools and other areas of health and representatives of health institutions, the consensus must be seen as a process of ongoing construction, which may require additions in the future.

It is assumed that communication should be centered on relationships, based on professionalism, universality, integrality and equity in health care for the population and encourage social participation, and based on the DCNs, theoretical references and scientific evidence. Specific objectives are described to develop competence in communication in the medical graduate, covering the theoretical foundations, the search, critical evaluation of the literature, preparation and writing of documents, and intrapersonal and interpersonal communication to make the medical graduate competent in communicating with people involved in the academic-scientific environment and in health care and health management. It is recommended the inclusion of communication in the curriculum from the beginning to the end of the course, integrated with other contents and areas of knowledge.

The moments in which each objective must be developed in the course were not established, considering the peculiarities of the curriculum of each school and their autonomy in its planning.

We hope the consensus will contribute to the review of curricula of undergraduate courses in medicine that already contain communication or to its implementation, and, perhaps, in the curricula of medical residencies in Brazil, to promote communication in medical education, in the attention to individual and collective health and in health management, to strengthen the SUS and achieve social transformations that improve the population’s health conditions and the defense of social justice.

The next objective of this ABEM project is to offer teaching materials and workshops to support teacher development in the teaching of communication.

Finally, we clarify that, just like any collective construction process, this consensus can be updated when necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Houaiss A, Villar MS, Franco FMM. Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva; 2001. [ Links ]

2. Araújo IS, Cardoso JM. Comunicação e saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2007. [ Links ]

3. Freire P. Extensão ou comunicação? São Paulo: Paz e Terra; 2014. [ Links ]

4. Freire P. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à autonomia. São Paulo: Paz e Terra ; 2004. [ Links ]

5. Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(1):5-15. [ Links ]

6. Kaba R, Sooriakumaran P. The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. Int J Surg. 2007;5(1):57-65. [ Links ]

7. Engel GL. The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1978;310(1):169-81. [ Links ]

8. Rogers CR. The foundations of the person-centered approach. Education. 1979;100(2):98-107. [ Links ]

9. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423-33. [ Links ]

10. Ong LM, De Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903-18. [ Links ]

11. Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25-38. [ Links ]

12. Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, Wang X, Rossi G, Hojat M, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1243-9. [ Links ]

13. Teutsch C. Patient-doctor communication. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87(5):1115-45. [ Links ]

14. Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826-34. [ Links ]

15. Roter DL, Hall JA. Studies of doctor-patient interaction. Annu Rev Public Health. 1989;10(1):163-80. [ Links ]

16. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med . 2011;86(3):359-64. [ Links ]

17. Riedl D, Schüßler G. The influence of doctor-patient communication on health outcomes: a systematic review. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2017;63(2):131-50. [ Links ]

18. World Health Organization, World Alliance for Patient Safety. Patients for patient safety: statement of case. Geneva; 2013 [acesso em 10 jan 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/PFPS_brochure_2013.pdf . [ Links ]

19. World Health Organization. WHO patient safety curriculum guide: multi-professional edition. Geneva: WHO. 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501958 . Acesso 10 jan. 2021. [Marra VN, Sette ML, coordenadores. Guia curricular de segurança do paciente da Organização Mundial da Saúde: edição multiprofissional. Rio de Janeiro: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro; 2016 [acesso em 10 jan. 2021]. Disponível em: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/patient-safety/9788555268502-por519565d3-e2ff-4289-b67f-4560fcd33b9d.pdf?sfvrsn=9e58a092_1.] [ Links ]

20. Marchon SG. A segurança do paciente sob cuidado na atenção primária à saúde [tese] Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2015. [ Links ]

21. Francisco A, Acquesta AL, Cunha BM. Gil CG, Pereira DA, Hahne FS et al. Cartilha sobre segurança do paciente sob cuidado. Projeto de Reestruturação de Hospitais Públicos do Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz. Coordenação Geral de Atenção Hospitalar - CGHOSP. 2019 [acesso em 28 nov 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://proqualis.net/sites/proqualis.net/files/CARTILHA_RHP_Digital.pdf . [ Links ]

22. Brasil. Documento de referência para o Programa Nacional de Segurança do Paciente/ Ministério da Saúde; Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2014 [acesso em 20 dez 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/ razilian o/documento_referencia_programa_nacional_seguranca.pdf . [ Links ]

23. Clapper TC, Ching K. Debunking the myth that the majority of medical errors are attributed to communication. Med Educ. 2020; 54(1):74-81. [ Links ]

24. Mickan SM, Rodger SA. Effective health care teams: a model of six characteristics developed from shared perceptions. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(4):358-70. [ Links ]

25. Mickan SM. Evaluating the effectiveness of health care teams. Aust Health Rev. 2005; 29(2):211-7. [ Links ]

26. Omura M, Maguire J, Levett-Jones T, Stone TE. The effectiveness of assertiveness communication training programs for healthcare professionals and students: a systematic review. Intern J Nurs Stud. 2017;76:120-8. [ Links ]

27. O’Connor P, Byrne D, O’Dea A, McVeigh TP, Kerin MJ. “Excuse me”: teaching interns to speak up. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(9):426-31. [ Links ]

28. Wittenberg E, Goldsmith JV, Chen C, Prince-Paul M, Johnson RR. Opportunities to improve Covid-19 provider communication resources: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns . 2021;104(3):438-51. [ Links ]

29. Gustavsson ME, Arnberg FK, Juth N, von Schreeb J. Moral distress among disaster responders: what is it? PDM. 2020;35(2):212-9. [ Links ]

30. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evan T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: tranforming educatino to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923-58. [ Links ]

31. Capra F, Eichemberg NR. A teia da vida: uma nova compreensão científica dos sistemas vivos. São Paulo: Cultrix; 2006; [ Links ]

32. Brasil. Resolução CNE/CES nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União; 2014. [ Links ]

33. Tresolini CP, The Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health professions education and relationship-centered care. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission; 2000. [ Links ]

34. Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S40-4. [ Links ]

35. Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-centered care. J Gen Intern Med . 2006;21(Suppl1):S3-8. [ Links ]

36. Kreps GL. Relational communication in health care. Southern Speech Communication Journal. 2009;53(4):344-59. [ Links ]

37. Gilligan C, James EL, Snow P, Outram S, Ward BM, Powell M, et al. Interventions for improving medical students’ interpersonal communication in medical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2(2):CD012418. [ Links ]

38. Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P, Scholfield T. The new consultation: developing doctor-patient communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [ Links ]

39. Makoul G. The SEGUE framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns . 2001;45(1):23-34. [ Links ]

40. Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med . 2003;78(8):802-9. [ Links ]

41. Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ . 1996;30(2):83-9. [ Links ]

42. Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. Perm J. 1999;3(3):79-88. [ Links ]

43. Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M, Maguire P, Lipkin M, Novack D, et al. Doctor-patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement. BMJ. 1991;303(6814):1385-7. [ Links ]

44. Makoul G, Schofield T. Communication teaching and assessment in medical education: an international consensus statement. Patient Educ Couns . 1999;37(2):191-5. [ Links ]

45. Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med . 2001;76(4):390-3. [ Links ]

46. Von Fragstein M, Silverman J, Cushing A, Quilligan S, Salisbury H, Wiskin C, et al. UK consensus statement on the content of communication curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ . 2008;42(11):1100-7. [ Links ]

47. Kiessling C, Dieterich A, Fabry G, Hölzer H, Langewitz W, Mühlinghaus I, et al. Communication and social competencies in medical education in German-speaking countries: The Basel Consensus Statement. Results of a Delphi Survey. Patient Educ Couns . 2010;81(2):259-66. [ Links ]

48. Bachmann C, Abramovitch H, Barbu CG, Cavaco AM, Elorza RD, Haak R, et al. A European consensus on learning objectives for a core communication curriculum in health care professions. Patient Educ Couns . 2013;93(1):18-26. [ Links ]

49. Garcia de Leonardo C, Ruiz-Moral R, Caballero F, Cavaco A, Moore P, Dupuy LP, et al. A Latin American, Portuguese and Spanish consensus on a core communication curriculum for undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ . 2016;16(1):1-16. [ Links ]

50. Bachmann C, Kiessling C, Härtl A, Haak R. Communication in health professions: a European consensus on inter-and multi-professional learning objectives in German. GMS J Med Educ . 2016;33(2):Doc23. [ Links ]

51. Noble LM, Scott-Smith W, O’Neill B, Salisbury H. Consensus statement on an updated core communication curriculum for UK undergraduate medical education. Patient Educ Couns . 2018;101(9):1712-9. [ Links ]

52. Medical Professionalism Project. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians’ charter. Lancet . 2002;359(9305):520-2. [ Links ]

53. Arnold L, Stern DT. What is medical professionalism. In: Stern DT, editor. Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. P.15-37. [ Links ]

54. Sullivan WM. Medicine under threat: professionalism and professional identity. CMAJ . 2000;162(5):673-5. [ Links ]

55. Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2014;36(1):47-61. [ Links ]

56. Rabow MW, Remen RN, Parmelee DX, Inui TS. Professional formation: extending medicine’s lineage of service into the next century. Acad Med . 2010;85(2):310-7. [ Links ]

57. Bloom SW. The doctor and his patient: a sociological interpretation. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 1963. [ Links ]

58. Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston W, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman T. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. California: Sage; 1995. [ Links ]

59. Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Radcliffe; 2005. [ Links ]

60. Fortin VI AH, Dwamena FC, Frankel RM, Smith RC. Smith’s patient centered interviewing: an evidence-based method. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2012. [ Links ]

61. Chou C, Cooley L, editors. Communication RX: transforming healthcare through relationship-centered communication. New York: McGraw Hill ; 2018. [ Links ]

62. Dohms M, Gusso G, organizadores. Comunicação clínica: aperfeiçoando os encontros em saúde. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2021. [ Links ]

63. Abrantes VLC. O IBGE e a formação da nacionalidade: território, memória e identidade em construção. Simpósio Nacional de História, 24, São Leopoldo, RS. Anais eletrônicos. São Leopoldo: Unisinos, 2007 [acesso em 10 abr 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://anpuh.org.br/uploads/anais-simposios/pdf/2019-01/1548210563_70ce6df73e2768b3f47ecdec48e2b97f.pdf . [ Links ]

64. Brasil. Lei nº 8.080, de 19 de setembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre as condições para a promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde, a organização e o funcionamento dos serviços correspondentes e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União ; 20 set 1990. [ Links ]

65. Paim JS, Silva LMV. Universalidade, integralidade, equidade e SUS. BIS Bol Inst Saúde. 2010;12(2):109-14. [ Links ]

66. Brasil. HumanizaSUS: política nacional de humanização: documento base para gestores e trabalhadores do SUS/Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria-Executiva, Núcleo Técnico da Política Nacional de Humanização. 2ª ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2004 [acesso em 20 dez 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/ razilian o/humanizaSUS_politica_nacional_humanizacao.pdf . [ Links ]

67. Brasil. Resolução CNE/CES nº 4, de 7 de novembro de 2001. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina. Diário Oficial da União ; 9 nov 2001. [ Links ]

68. Brasil. Lei nº 12.871, de 22 de outubro de 2013. Institui o Programa Mais Médicos, altera as Leis nº 8.745, de 9 de dezembro de 1993, e nº 6.932, de 7 de julho de 1981, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União ; 23 out 2013. [ Links ]

69. Grosseman S, Loures L, Mariussi A, Grossman E, Muraguchi E. Projeto ensino de habilidades de comunicação na área da saúde: uma trajetória inicial. Cad Abem. 2014;10:7-12. [ Links ]

70. Grosseman S, Lampert JB, Soliani ML, Dohms M, Novack D. Projeto Abem: Ensino de comunicação na área da saúde. Associação Brasileira de Educação Médica; 2020 [acesso em 3 dez 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://website.abem-educmed.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Hist%C3%B3rico-projeto-HC.pdf . [ Links ]

71. Innes JE, Booher DE. Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: a framework for evaluating collaborative planning. JAPA. 1999;65(4):412-23. [ Links ]

72. Innes JE. Consensus building: clarifications for the critics. Planning Theory. 2004;3(1):5-20. [ Links ]

73. Yi-chong X. Timeline - Covid-19: events from the first identified case to 15 April. Social Alternatives. 2020;39(2):60-3. [ Links ]

74. Brasil. Portaria no 2.761, de 19 de novembro de 2013. Institui a Política Nacional de Educação Popular em Saúde no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - PNEP-SUS. Diário Oficial da União ; 20 nov 2013 [acesso em 20 dez 2021]. Disponivel em: Disponivel em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2013/prt2761_19_11_2013.html . [ Links ]

75. Rosenberg MB. Comunicação não violenta: técnicas para aprimorar relacionamentos pessoais e profissionais. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Ágora; 2006. [ Links ]

76. Freire P, Faundez A. Por uma pedagogia da pergunta. São Paulo: Paz e Terra ; 2011. [ Links ]

77. Gunio MJ. Determining the influences of a hidden curriculum on students’ character development using the Illuminative Evaluation Model. JCSR. 2021;3(2):194-206. [ Links ]

78. Freire P. Pedagogia da esperança: um reencontro com a pedagogia do oprimido. São Paulo: Paz e Terra ; 2014. [ Links ]

79. Bakhtin M. Estética da criação verbal. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes; 1997. [ Links ]

80. Bakhtin M. Marxismo e Filosoia da linguagem: problemas fundamentais do método sociológico na ciência da linguagem. 16ª ed. São Paulo: Hucitec; 2014. [ Links ]

81. Venosa B, Bastos LC. Goffman e a ritualização do infinitamente pequeno: observando o sutil na sustentação do discurso hegemônico em interações de um curso de marcenaria para mulheres. Veredas - Revista de Estudos Linguísticos. 2021;25(1):140-63. [ Links ]

82. Berger PL. Perspectivas sociológicas: uma visão humanística. Petrópolis: Vozes; 2007. [ Links ]

83. Berger PL., Luckmann T. A construção social da realidade: tratado de sociologia do conhecimento. Petrópolis: Vozes ; 2007. [ Links ]

84. Bourdieu P. O poder simbólico. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil; 2000. [ Links ]

85. Hyland K. Metadiscourse: what is it and where is it going? JoP. 2017;113:16-29. [ Links ]

86. Jaworski A, Coupland N, Galasinski D. Metalanguage: social and ideological perspectives. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 2004. [ Links ]

87. Goleman D, Boyatzis R, McKee A. O poder da inteligência emocional. Rio de Janeiro: Campus; 2002. [ Links ]

88. Del Prette ZAP, Del Prette AD. Psicologia das habilidades sociais: diversidade teórica e suas implicações. Petropólis: Vozes; 2009. [ Links ]

89. Hojat M. Empathy in health professions education and patient care. New York: Springer; 2016. [ Links ]

90. Lunenburg, FC. Louder than words: the hidden power of nonverbal communication in the workplace. IJ SAID. 2010;12(1):1-5. [ Links ]

91. Craig RT. Metacommunication. In: Jensen KB, Rothenbuhler EW, Pooley JD, Craig RT, editors. The international encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. 2016. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect232. [ Links ]

92. Watzlawick P, Beavin JH, Jackson DD. Pragmática da comunicação. São Paulo: Culturix; 2010. [ Links ]

93. Bosco FM, Tirassa M, Gabbatore I. Why pragmatics and theory of mind do not (completely) overlap. Front Psych. 2018;9:1453. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01453. [ Links ]

94. Elsahar Y, Hu S, Bouazza-Marouf K, Kerr D, Mansor A. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) advances: a review of configurations for individuals with a speech disability. Sensors. 2019;19(8):1911. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/s19081911. [ Links ]

95. Panham HMS. Comunicação suplementar e alternativa. In: Ortiz KZ. Distúrbios neurológicos adquiridos: fala e deglutição. São Paulo: Manole; 2006. [ Links ]

96. Araújo GS, Paulo AMF, Neta HHS, Costa LB, Santos SNDSF, Lima ILB. Benefícios da tecnologia de comunicação aumentativa e alternativa em pacientes oncológicos. Revista Saúde & Ciência online. 2018;7(2):145-56. [ Links ]

97. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Augmentative and Alternative Communication [acesso em 20 em 2022]. Disponível em: www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Professional-Issues/Augmentative-and-Alternative-Communication/. [ Links ]

98. Gomes CA, Rugno FC, Rezende G, Cardoso RC, De Carlo MM. Tecnologia de comunicação alternativa para pessoas laringectomizadas com câncer de cabeça e pescoço. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto). 2016;49(5):463-74. [ Links ]

99. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. TeamStepps 2.0, Team Strategies & Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety: Pocket guide. AHRQ Pub. No. 14-0001-2. Revised December 2013 [acesso em 10 set 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/pocketguide.pdf . [ Links ]

100. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302-11. [ Links ]

101. Rabow MW. Beyond breaking bad news: how to help patients who suffer. WJM. 1999;171:260-3. [ Links ]

102. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1975-8 [ Links ]

103. Narayanan V, Bista B, Koshy C. BREAKS protocol for breaking bad news. IJPC. 2010;16(2):61-5. [ Links ]

104. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Comunicação eficaz com a mídia durante emergências de saúde pública: um manual da OMS. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2009. [Tradução de: WHO. Effective Media Communication during Public Health Emergencies: a WHO Handbook; 2007.] [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/ razilian o/ razilian o_eficaz_midia_durante_emergencias.pdf. [ Links ]

105. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Crisis+Emergencies risk communication. 2014 [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/cerc_2014edition_Copy.pdf . [ Links ]

106. Center for Disease control and prevention. Emergency preparedness and response: CERC Manual updates [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp . [ Links ]

107. World Health Organization. Communicating risk in public health emergencies: a WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC) policy and practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259807/9789241550208-eng.pdf . [ Links ]

108. World Health Organization. Covid-19 global risk communication and community engagement strategy, December 2020-May 2021: interim guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2020 [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338057 . [ Links ]

109. IRFC, Unicef, WHO. RCCE action plan guidance: COVID-19 preparedness & response. 2020 [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: file:///G:/Documents/Habilidades_comunicacao/2022/covid19-rcce-guidance-final-brand%20(1).pdf. [ Links ]

110. The international Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). What is a disaster? [acesso em 10 fev 2021]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ifrc.org/what-disaster . [ Links ]

111. Secretaría Interinstitucional de la Estrategia Internacional para la Reducción de Desastres, Naciones Unidas. Vivir con el riesgo: informe mundial sobre iniciativas para la reducción de desastres. Genebra: ONU; 2004. [ Links ]

112. Corrêa M, Del Castanhel F, Grosseman S. Percepção de pacientes sobre a comunicação médica e suas necessidades durante internação na unidade de cuidados intensivos. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2021;33:401-11. [ Links ]

113. Kynoch K, Chang A, Coyer F, McArdle A. The effectiveness of interventions to meet family needs of critically ill patients in an adult intensive care unit: a systematic review update. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2016;14(3):181-234. [ Links ]

114. Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: a systematic review. Chest. 2011;139(3):543-54. [ Links ]

115. Ju XX, Yang J, Liu XX. A systematic review on voiceless patients’ willingness to adopt high-technology augmentative and alternative communication in intensive care units. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 2021;63:102948. [ Links ]

116. Ten Hoorn S, Elbers PW, Girbes AR, Tuinman PR. Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):1-14. [ Links ]

117. Seaman JB, Arnold RM, Scheunemann LP, White DB. An integrated framework for effective and efficient communication with families in the adult intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):1015-20. [ Links ]

118. Cypress BS. Family conference in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. DCCN. 2011;30(5):246-55. [ Links ]

119. Brooks LA, Bloomer MJ, Manias E. Culturally sensitive communication at the end-of-life in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Austr Crit Care . 2019;32(6):516-23. [ Links ]

120. Carvalho RT, Parsons HÁ, organizadores. Manual de cuidados paliativos ANCP. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Academia Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos; 2012 [acesso em 20 jan 2022]. Disponível em: file:///G:/Documents/Habilidades_comunicacao/2022/manual_de_cuidados_paliativos_ancp.pdf. [ Links ]

121. Borges MM, Santos Junior R. A comunicação na transição para os cuidados paliativos. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2014;38(2):275-82. [ Links ]

122. Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, Clayton JM. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Pat Educ and Couns. 2016;99(1):3-16. [ Links ]

123. Ngo-Metzger Q, August KJ, Srinivasan M, Liao S, Meyskens Jr FL. End-of-life care: guidelines for patient-centered communication. Am Fam Physician . 2008;77(2):167-74. [ Links ]

124. Schrijvers D, Cherny NI. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines on palliative care: advanced care planning. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:iii138-iii42. [ Links ]

125. Knox K, Parkinson J, Pang B, Fujihira H, David P, Rundle-Thiele S. A systematic literature review and research agenda for organ donation decision communication. PIT. 2017;27(3):309-20. [ Links ]

126. Jacoby L, Crosier V, Pohl H. Providing support to families considering the option of organ donation: an innovative training method. PIT . 2006;16(3):247-52. [ Links ]

LIST OF ALL CONSENSUS’ PARTICIPANTS WHO AGREED TO THE DISCLOSURE OF THEIR NAMES AND INSTITUTIONS

Suely Grosseman (ABEM project coordinator)

Facilitators: Newton Key Hokama (coordinator of the virtual communication group WebComunica Brasil) and Evelin Massae Ogatta Muraguchi (reporting of the consensus workshops)

CEOs of the ABEM administrations that supported the project: Jadete Barbosa Lampert, Sigisfredo Luis Brenelli and Nildo Alves Batista

Ádala Nayana de Sousa Mata - Escola Multicampi de Ciências Médicas do Rio Grande do Norte /Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Agnes de Fátima Pereira Cruvinel - Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul

Alessandra Vitorino Naghettini - Universidade Federal de Goiás

Alice Mendes Duarte - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Alicia Navarro de Souza - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Ana Cristina Franzoi - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Ana Paula Mariussi - Universidade da Região de Joinville

Cacilda Andrade de Sá - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora

Cáthia Costa Carvalho Rabelo - Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais e Santa Casa de Minas Gerais

Cecilia Emília De Oliveira Creste - Universidade do Oeste Paulista

Danielle Bivanco-Lima - Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo

David Araujo Júnior - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Denise Herdy Afonso - Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro

Dolores Gonzales Borges de Araújo - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Elaine Fernanda Dornelas de Souza - Universidade do Oeste Paulista

Eleusa Gallo Rosenburg - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Eliane Perlatto Moura - Universidade João do Rosário Vellano

Eloisa Grosseman - Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

Erotildes Maria Leal - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Evelin Massae Ogatta Muraguchi - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Campus Londrina

Fernanda Patrícia Soares Souto Novaes - Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco

Guilherme Antonio Moreira de Barros - Universidade Estadual Paulista

Gustavo Antonio Raimondi - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Helena Borges Martins da Silva Paro - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Hermila Tavares Vilar Guedes - Universidade do Estado da Bahia

Iago Amado Peres Gualda - Universidade Estadual de Maringá

Ilza Martha de Souza - Universidade do Oeste Paulista

Irani Ferreira da Silva Gerab - Universidade Federal de São Paulo

Ivana Lucia Damásio Moutinho - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora

João Carlos da Silva Bizario - Faculdade de Medicina de Olinda

José Maria Peixoto - Universidade João do Rosário Vellano

Josemar de Almeida Moura - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

Juliana Guerra - Faculdade Pernambucana de Saúde

Lara de Araújo Torreão - Universidade Federal da Bahia

Lara Cristina Leite Guimarães Machado - Universidade da Região de Joinville

Laura Bechara Secchin - Faculdade de Ciências Médicas e da Saúde de Juiz de Fora

Leandro Francisco Moraes Loures - Universidade da Região de Joinville

Liliane Pereira Braga - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Luiza De Oliveira Kruschewsky Ribeiro - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Marcela Dohms - Vice-presidente da Associação Brasileira Balint

Márcia Helena Fávero de Souza - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora

Maria Amélia Dias Pereira - Universidade Federal de Goiás

Maria de Fátima Aveiro Colares - Centro Universitário Municipal de Franca

Maria Eugenia V. Franco - Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso

Maria Luísa Soliani - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Maria Viviane Lisboa de Vasconcelos - Universidade Federal de Alagoas

Mariana Maciel Nepomuceno - Universidade Federal de Pernambuco

Marianne Regina Araújo Sabino - Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Pernambuco

Marta Silva Menezes - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Mauricio Abreu Pinto Peixoto - Instituto Nutes da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Milene Soares Agreli - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Miriam May Philippi - Centro Universitário de Brasília

Mônica da Cunha Oliveira - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Mônica Daltro - Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública

Newton Key Hokama - Universidade do Estado de São Paulo, Botucatu

Nilva Galli - Universidade do Oeste Paulista

Paulo Pinho - Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

Paulo Roberto Cardoso Consoni - Universidade Luterana do Brasil

Priscila Maria Alvares Usevicius - Universidade Evangélica de Goiás

Renata Rodrigues Catani - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Rosana Alves- Faculdades Pequeno Príncipe

Rosuita Fratari Bonito - Faculdade do Trabalho de Uberlândia

Sandra Torres Serra - Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro

Simone Appenzeller - Universidade Estadual de Campinas

Simone da Nóbrega Tomaz Moreira - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Solange de Azevedo Mello Coutinho - Escola de Medicina Souza Marques

Suely Grosseman - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina e Faculdades Pequeno Príncipe

Ubirajara João Picanço de Miranda Junior - Escola Superior de Ciências da Saúde

Valéria Goes - Universidade Federal do Ceará

Received: October 09, 2021; Accepted: June 15, 2022

texto em

texto em