Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versão impressa ISSN 0100-5502versão On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.46 no.3 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 09-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v46.3-20210006

REVIEW ARTICLE

Interprofessional Education in Health training in Brazil: Scoping Review

1Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brasil.

2Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Bauru, São Paulo, Brasil.

Introduction:

Interprofessional education (IPE) can be used to improve health care by promoting opportunities for students to develop competencies for teamwork, collaborative practice and comprehensive care. However, the effects of IPE implementation in the Brazilian context need to be explored.

Objective:

To map the Brazilian scientific production on the learning of students attending health courses in the context of IPE, challenges and advances for educators and management.

Method:

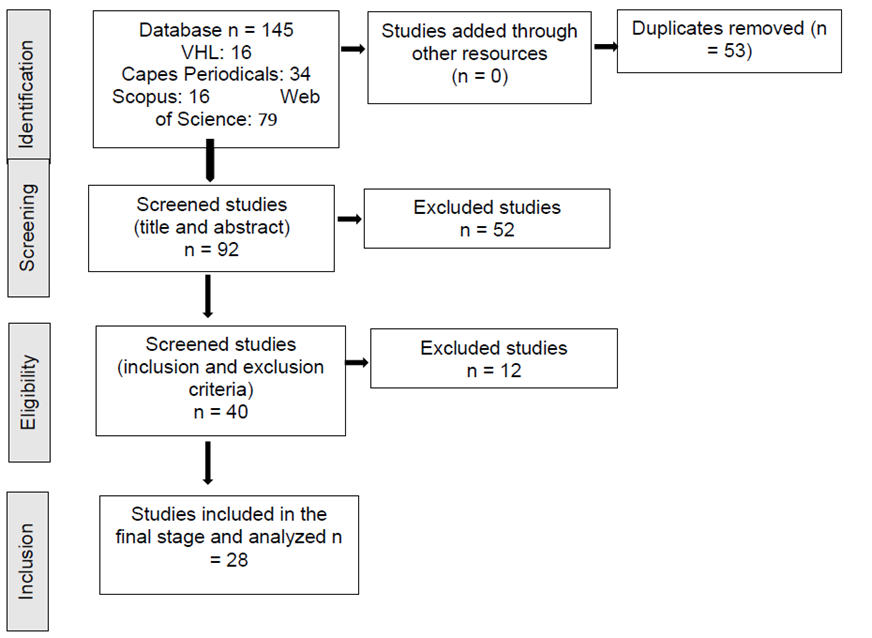

A scoping review was carried out to answer the following question: How does student learning occur in formative processes that use the IPE approach from the viewpoint of students, educators and managers? The search took place in the Web of Science databases, Capes, Scopus and Virtual Health Library, using the descriptor/keyword “interprofessional education.” Publications were searched from 2010 to 2020, published in Portuguese, English or Spanish, of which Brazil was the country of publication or origin of the study. We identified 145 studies; 53 were duplicated, 92 were analyzed, and 28 comprised the final sample. The findings were organized into “IPE from the student’s perspective,”; “ IPE from the educators’ perspective,”; “Advances and challenges in teaching and health management,”; “Recommendations for IPE in the Brazilian context.”

Results:

The target audience involved students, residents, facilitators and health staff, totaling 2,886 participants. Learning according to the IPE allows the student to recognize the integrality of patient care and the SUS as the guide of health actions. The facilitator is relevant in developing collaborative work but has little pedagogical training, motivation, and institutional support. Management understands IPE as a complementary tool, supporting other Brazilian politician reforms, but efforts are needed to promote teaching-service-community integration and endorse the integrated curriculum.

Conclusion:

By mapping IPE, it was identified that the studies are aligned with the SUS to transform the training and qualification of care, demonstrating the potential of IPE for health curricula. Student learning, mediated by interprofessionality, has facilitated the development of the competencies required to meet the DCNs and the needs of the SUS, despite the various challenges faced by the students, educators and management.

Keywords: Interprofessional Education; Health Human Resource Training; Learning; Students, Health Occupations

Introdução:

A educação interprofissional (EIP) pode ser um caminho para aprimorar o cuidado em saúde ao promover oportunidades para que estudantes desenvolvam competências para trabalho em equipe, prática colaborativa e integralidade do cuidado; contudo, os efeitos da implementação da EIP no Brasil precisam ser explorados.

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivo mapear a produção científica brasileira sobre a aprendizagem de alunos de cursos da saúde no contexto da EIP, os desafios e os avanços para formadores e gestão.

Método:

Trata-se de uma scoping review para responder à seguinte questão: “Como tem ocorrido a aprendizagem de estudantes brasileiros em processos formativos que utilizam a abordagem da EIP na visão do estudante, formador e gestor?”. A busca ocorreu nas bases Web of Science, Periódicos Capes, Scopus e Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde, com o descritor/palavra-chave “educação interprofissional”. Buscaram-se trabalhos de 2010 a 2020, publicados em português, inglês ou espanhol, em que o Brasil foi o país de publicação ou de origem do estudo. Identificaram-se 145 estudos, dos quais 53 eram duplicados. Analisaram-se 92, e 28 compuseram a amostra final. Os achados foram organizados em “EIP na perspectiva do estudante”; “Formadores na ótica da EIP”; “Avanços e desafios na gestão de ensino e saúde”; “Recomendações para EIP no contexto brasileiro”.

Resultado:

O público-alvo envolveu estudantes, residentes, formadores e equipe de saúde, totalizando 2.886 participantes. A aprendizagem na lógica da EIP permite ao estudante reconhecer a integralidade da assistência ao paciente e o SUS como norteador das ações de saúde. Os formadores são relevantes no desenvolvimento do trabalho colaborativo, mas têm pouca capacitação pedagógica, pouca motivação e pouco apoio institucional. A gestão compreende a EIP como ferramenta complementar no apoio a outras reformas brasileiras, contudo esforços são necessários para a integração ensino-serviço-comunidade e a promoção do currículo integrado.

Conclusão:

Quando se realizou o mapeamento sobre EIP, identificou-se que os estudos estão alinhados com o SUS para a transformação da formação e a qualificação do cuidado, demonstrando a potencialidade da EIP para os currículos da saúde. A aprendizagem de alunos, mediada pela interprofissionalidade, tem facilitado o desenvolvimento das competências requeridas, de modo a atender às DCN e às necessidades do SUS, apesar dos diversos desafios enfrentados pelos estudantes, formadores e gestores.

Palavras-chave: Educação Interprofissional; Capacitação de Recursos Humanos em Saúde; Aprendizagem; Estudantes de Ciências da Saúde

INTRODUCTION

Data from the Pan American Health Organization show there are millions of people in the Americas who suffer from lack of access to health services, making it a challenge to guarantee quality services1. To face the challenges related to the assistance and comprehensive health care, interprofessional education (IPE) in health has been a strategy for the development of collaborative practices that meet the health demands2)-(5. IPE takes place when students from two or more professions learn about the others, with others and with each other through collaboration, favoring better health outcomes, aiming at the training of professionals with skills, knowledge and attitudes to develop collaborative care that contributes for the well-being of the community2)-(6.

The alignment and collaboration between health, education services and the community involved in health and education promotion and assistance are essential for IPE to occur1)-(7. In Brazil, the Unified Health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde) is the current health management model and has as one of its guiding principles the integrality of care with a focus on quality of life, health prevention and promotion. For its consolidation, it is necessary to reorientate health training and work3. The IPE as an educational proposal favors training aimed at the SUS, as it contributes to the decrease in the fragmentation of care and relationships between professionals. Additionally, the IPE strengthens the health system by promoting the training of professionals who are more prepared to: 1) understand the user as the center of health actions and policies, 2) work collaboratively as a team and 3) recognize the interdependence of areas to solve problems, complex health needs, and necessary conditions for comprehensive health care8),(9. Although the health training model is still predominantly uniprofessional, the process of changing the health professionals’ training in accordance with the SUS principles has been taking place since 1980 through several initiatives, such as the UNI program, the National Education Forum, Family Health, Multiprofessional Residency in Health (RMS, Residência Multiprofissional em Saúde) and integrative courses during undergraduate school8),(10.

To support the professional training process, several contributory policies that promote IPE were developed9),(10. At undergraduate school, the implementation of the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCNs, Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais) of the Undergraduate Health Courses in 2001, indicate the adoption of an integrated and interprofessional-based curriculum that advocates training for teamwork from the perspective of integrality and quality of care3),(10, although it does not yet explicitly mentions the IPE. It was only in 2014 that the IPE started to be associated as a policy that promoted training when it was mentioned in the DCNs of the medical courses5),(11)-(12.

The Multiprofessional Residency in Health (RMS, Residência Multiprofissional em Saúde) was created in 2005 at the postgraduate school level13, where the specificities of each profession were preserved and the recognition of common areas of professional activity, aiming at the promotion and comprehensive health care, was established4),(10. Other initiatives that promote IPE include the National Program for Reorientation of Professional Training in Health (Pró-Saúde) and the Education Program for Work in Health (PET-Saúde), which prepare students to provide comprehensive health care, by integrating teaching-service and teamwork4),(9),(10.

The first studies on the results of Brazilian IPE for the promotion of comprehensive care in line with the SUS were published in 20113),(11; however, the effects of its implementation are little known. This study aims to map Brazilian scientific production on the learning of students attending health courses in the context of IPE, challenges and advances for educators and management, while seeking to contribute with data on the results of Brazilian IPE initiatives.

METHOD

The scoping review was adopted to comprehensively identify the existing literature on IPE15, considering the checklist proposed by PRISMA-ScR16. The scoping review was chosen because it allows the synthesis and analysis of available scientific knowledge17, without restricting the parameters for randomized clinical trials or requiring study quality evaluation18.

Five stages19 were used: (1) research question; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data mapping; (5) grouping and summarizing data.

In stage 1, the research question19 was established, with P for Population: Brazilian health science students (undergraduate or postgraduate); Intervention: educational process; Issue of interest: interprofessional education; Result: learning opportunities; Time: studies published from 2010 to May 2020. The research question was: “How does student learning occur in formative processes that use the IPE approach from the viewpoint of students, educators and managers?”

Two independent researchers carried out stages 2 to 4; in case of discrepancies, a third evaluator was called in, who decided whether or not to include the article in that stage.

In stage 2, the search for studies took place between May 15 and 20, 2020 in the Web of Science, Capes Periodicals, Scopus and the Virtual Health Library (BVS) databases; the references of the included studies were also consulted in search for studies not identified in the databases. The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a health information specialist and included the keywords “educação interprofissional” OR “interprofessional education” for the Web of Science and Capes periodicals. In the Virtual Health Library (BVS) and Scopus, the descriptor “educação interprofissional” OR “interprofessional education” was used.

The filters included publications from the last 10 years (2010 to May 2020), language (Portuguese, English and Spanish), place of publication or country of origin of the study (Brazil); afterwards, the selection was performed manually. Studies in more than one database were considered only once.

In the third stage, studies that met the inclusion criteria were included: (1) original research carried out in Brazil; (2) research with undergraduate or postgraduate health students; (3) studies that included student learning outcomes.

Articles that (1) were not carried out in Brazil; (2) did not assess student learning outcomes; (3) reviews, comments, discussion or editorial articles, as well as theses and dissertations were excluded.

For the analysis of the included articles, the mapping of relevant information for the synthesis and interpretation of data represented the fourth stage. The data were extracted and mapped using an adapted instrument20: study identification, study topic, objectives, type of research/study design, participants, study setting, main results and conclusions.

In stage 521, the findings were grouped and summarized in a flowchart and then synthesized aiming to answer the review question.

RESULTS

The literature search resulted in 145 studies, of which 40 were read in full and 28 were included (Figure 1).

No publications were identified that met the selection criteria in the years 2010, 2012, 2019 and 2020 (until May). Studies from the years 201122, 201323),(24, 201425, 20153),(26)-(28, 201610),(29)-(32, 201733)-(36 and 20185),(14),(37)-(45 were selected.

The studies were characterized as qualitative3),(5),(10),(14),(24),(26),(28),(30),(33),(36),(38),(41),(43, quantitative31),(35),(37),(42),(44),(45, experience reports23)-(24),(27),(29),(32),(34),(39 and mixed22),(25),(40.

Of the total number of studies, 15 (53.6%) were developed in the Southeast3),(14),(22),(23),(25),(26),(30),(31),(34),(39)-(43),(45; nine (32.1%) in the Northeast10),(24),(28),(29),(35),(37),(38),(44 and four (14.3%) in the South region5),(27),(32),(36.

Of the 28 studies, 20 (71.4%) are related to the training of undergraduate students3),(5),(14),(22),(23),(25)-(32),(39),(42)-(45; whereas eight (28.6%) address RMS10),(24),(31),(33),(37),(38),(40),(41.

The IPE was investigated during practical teaching in primary care3),(5),(10),(14),(22)-(24),(26)-(32),(35),(37)-(43, in the hospital environment33, as an interprofessional discipline36 or in the assessment of scales25),(44),(45.

The target audience of the studies involved 2,343 students3),(5),(14),(22),(23),(25)-(30),(32),(34)-(37),(39),(42)-(45) of Medicine, Physical Education, Nursing, Pharmacy, Physiotherapy, Speech Therapy, Nutrition, Dentistry, Psychology, Social Work, Occupational Therapy, Veterinary Medicine, Public Policies, Biological Sciences, Biomedicine and Public Health and 392 residents10),(24),(31),(33),(37),(38),(40),(41; principals, professors, tutors, preceptors, managers of health units and hospital workers also participated, totaling 2,886 participants.

To answer the research question, the analyzed results were grouped into four topics: “IPE from the student’s perspective,”; “IPE from the educators’ perspective”; “Advances and challenges in teaching and health management,”; “Recommendations for IPE in the Brazilian context.’

IPE from the student’s perspective

Table 1 shows the topic “IPE from the student’s perspective”, highlighting the general aspects of undergraduate and residency courses in health that can facilitate or challenge learning in IPE. While IPE was facilitated during undergraduate school, major challenges occurred during RMS and issues associated with services and educators were identified at both levels of professional training.

Table 1 General aspects that facilitate or challenge the application of IPE in health student learning, 2020

| IPE and learning | General aspects | Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Undergraduate school | Activities in the field of practice | 3,5,10,14, 26-36, 38-43 |

| Opportunity to work with other colleagues and professionals | 5,14,22,23, 25,26,28,32,36 | ||

| Student motivation and Availability for new experiences | 10,22,26 | ||

| Implementation of the IPE strategy in the initial years of the courses | 14,22,24,25, 36 | ||

| Enthusiasm for the course | 25,28,36 | ||

| Involvement of students in PET-Health | 26,35 | ||

| Female students | 35,44 | ||

| Students attending the early years of the course - committed and believe in the exchange of knowledge | 36,44 | ||

| Physical Education, Nutrition and Psychology students are more available for collaboration | 42 | ||

| Pharmacy students have more collaborative attitudes than medical students (self-perception of authority) | 44 | ||

| Challenges | Undergraduate school | Graduates have less availability for collaborative practice | 36,44 |

| Early start of practical activities - unprepared, immature, with stereotyped conceptions about the profession | 14, 36,42 | ||

| Residency | Lack of interprofessional experience in undergraduate studies impact on the integration and recognition of their role in the team | 5,10,14,22, 24,32,37-39,41,43-45 | |

| Difficulty with IPE - significant demand | 28,37,41 | ||

| Difficulty with IPE - specialized view of one’s area | 38,40,41 | ||

| Teaching Service Community | Little articulation x resistance of professionals to include students/residents into teams; difficulty in creating interprofessional teams | 26,28,34, 43 | |

| Lack of adequate place to welcome students and integrate them | |||

| Educators | Preceptors’ unpreparedness | 26,28,34, 43 | |

| Little time for supervision | |||

The learning built by undergraduate students and residents when they had their training mediated by the IPE are shown in table 2.

Table 2 Learnings built by undergraduate students and residents attending programs that used the IPE, 2020

| Type of course | Learning | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate school | Promotion of recognition, reflection of roles and professional interdependence for integrated care | 5,14,22,23, 25-26, 28,29,36 |

| Minimizing prejudice among professions | ||

| Perception of the importance of collective spaces for the construction of narratives as stimulators for teamwork, development of listening skills, negotiation, dialogue, decision-making, respect for differences | 5,10,22,23, 26,27,35,38 | |

| Perception that teaming up isn’t just randomly gathering colleagues | 10,38,40,42 | |

| Facilitating the understanding of the SUS | 25,36 | |

| Satisfaction and valuing of the opportunity to interact with other professionals | 25,28,36 | |

| Recognition of the patient included in a life context | 35,44,45 | |

| Recognition of the importance of teamwork and the knowledge of interprofessional professionals to solve problems Recognition of interprofessional work to solve cases of patients with complex problems | ||

| Multiprofessional Residency | Recognition of interprofessional work to solve cases of patients with complex problems | 24,38,40 |

| Recognition of each member’s role as collective knowledge builders | 24,38,40,41 | |

| Integration of actions and knowledges from different professional categories | 31,37 |

Educators from an IPE perspective

The educators were understood in this study as mentors, tutors or preceptors. Although the teacher has a relevant role in the development of the competence of collaborative work, challenges and efforts necessary for IPE were identified (Table 3).

Table 3 Challenges and efforts necessary for the implementation of IPE from the educators’ perception, 2020

| IPE Implementation | Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Lack of institutional support, bureaucracy in universities, departmentalized structure | 3, 26 |

| Emphasis on academic and postgraduate productivity | ||

| Obligation of individual workload control | ||

| Insufficient teaching-service articulation | ||

| Preceptors with previous uniprofessional training | 10,24,33 | |

| Students’ prejudice of educators from different areas | 14 | |

| Little supportive, normative educators and poor communication | 26,43 | |

| Students who are unprepared for early inclusion into practice | 34,39 | |

| Educators want to conduct learning and can prevent students from learning “on their own”. | ||

| Efforts | Pedagogical training | 5,10,14, 33,38,43 |

| Common language development among preceptors | ||

| Conversation circles | 26 | |

Advances and challenges in teaching and health management

The mapping of the research showed advances in the integration of interprofessionality, but there are many challenges to be overcome by the teaching and health managements (Table 4) for the effective implementation of IPE.

Table 4 Advances and challenges in teaching and health management for the implementation of the IPE, 2020

| IPE implementation | Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Advances | IPE as complementary in the support of Brazilian reforms: integration between universities x services x community | 26,37,38 |

| Challenges | To highlight the SUS principles | 3,5,22,33,41 |

| Selection of appropriate IPE teaching strategies | 5,10,42 | |

| Guarantee of collective reflection that goes beyond the standardization | 5,10,22,34,38,41 | |

| Promotion of an integrated curriculum that addresses collaboration skills in the early years of the courses | 5,35 | |

| Difficulties in the constitution of interprofessional teams due to the resistance of health services | 10,26,31,33,38,40,43 | |

| Inadequate articulation between teaching and service | 41 | |

| High professional turnover that challenges student communication and involvement | 41 | |

Recommendations for IPE in the Brazilian context

Some studies issued recommendations for the implementation of IPE in Brazil. In undergraduate teaching, the fight against the bureaucratization of actions and way of thinking about health is suggested, so that the learning experience can be creative and result in ethical professionals28; additionally, it is necessary to encourage a multidisciplinary and interprofessional work with theoretical and practical appropriation by all those involved to consolidate the SUS30 and understand the importance of interdisciplinary27 and collaborative30 practices in health education.

Regarding the teaching and service integration, studies recommend the participation of SUS managers in the regulation of professional training29),(40; the creation of a collaborative network aimed at strengthening the SUS30, aligned with the social and health needs of the population33.

The importance of establishing a dialogue and partnerships between higher education institutions that promote discussions on the need to implement IPE in health curricula29),(40 is highlighted.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that IPE has been implemented in several Brazilian contexts of professional training to qualify health care7 and promote the teaching-service-community integration2.

Among the issues that facilitate learning, practical activity has been mentioned as a strategy to develop interprofessional relationships in health education3),(5),(10),(14),(26)-(36),(38)-(43 and create opportunities for coexistence with other colleagues and professionals5),(14),(22),(23),(25),(26),(28),(32),(36, corroborating the literature in the area and international recommendations2),(46),(47),(48.

Interprofessional learning in the practice setting requires the interaction between knowledge, the environment, real-world experiences, individual skills and social intervention initiatives to promote an active and experiential learning about work in the health area49),(50. These experiences can stimulate academic protagonism in the way of thinking and doing health work50, in line with the DCNs of health courses, by promoting the sharing of knowledge, comprehensive care, understanding of the participation and the autonomy of its users49. Interprofessional practice also leads the students to develop a critical sense to make joint decisions with the team50.

For IPE to favor training and become part of the work of future health professionals, this strategy should be implemented at the start of the training and extend throughout the professional career7),(51. Similar to the findings of this scoping review on the Brazilian context21),(30, a systematic review showed that novice students are more available for IPE than graduate ones7),(51; moreover, they have a facilitator profile, are more motivated and open to new experiences, reinforcing the need for interprofessional activities to be offered throughout the course and in practical fields, so that graduates are trained to carry out interprofessional activities and collaborative practices7. However, in educational institutions that already use the interprofessional curriculum and the contact of students with collaborative activities52),(53, there was no difference in the availability for IPE between students attending the first years and the last year. These results were possibly impacted by the interprofessional curriculum already used in these institutions.

The challenges reported by the educators for the implementation of IPE in learning3),(10),(11), (26), (28), (34), (36), (39), (42)-(44) may result from the distancing between the academic universe and working in the real world50, the lack of institutional support, an adequate teaching-service articulation, incompatible curriculum and faculty training3),(26, which need to be overcome so that interprofessional work can be truly effective54. Therefore, it is necessary for the actors involved in this process reinvent themselves as professionals23),(34),(54. The depicted difficulties can be solved by collaborative networks between educational institutions to share learning experiences, curriculum remodeling, concept discussion and faculty development5),(48),(50),(54.

Furthermore, it is the educator’s responsibility to recognize their role as a facilitator in the IPE51),(53 to increase mutual appreciation, understanding and collaboration; to do so, the facilitator must learn from resources inside and outside the group, synthesize learning, eliminate the lack of communication and misunderstandings, resolve rivalries and conflicts, and transform problems into learning opportunities5),(7),(51),(53.

The PET-Saúde program and practical integrative undergraduate disciplines that used the IPE facilitated their students’ learning and were also positively evaluated by educators, service workers and service users.

PET-Saúde is aligned with the DCNs and its results are relevant in interprofessional practice and teaching-service-community integration by placing a student inside a real-life scenario, bringing them closer to the population’s social and health context and allowing spontaneous, constant and critical learning, in addition to the development of skills to promote patient-centered care28),(29.

The faculty’s participation in PET-Saúde, although challenging, is a positive experience for IPE. Interprofessional work makes educators review their teaching processes and seek creative solutions, bringing educators closer to those from other courses, reducing prejudice among professionals, increasing the recognition of roles and functions, and promoting learning about the service and SUS, improving collaboration. However, there is some resistance from the teaching staff to the inclusion of IPE in the curriculum and participation in interprofessional programs is usually the result of voluntary and personal motivations26. For health workers, PET contributes to teaching-service integration, as network professionals act as preceptors while carrying out pedagogical training and developing skills for interprofessional work and collaborative practices28),(29.

IPE experiences in integrative disciplines indicate that common activities contribute to training professionals who will value the integrality of care23),(50 by developing and understanding common, complementary and collaborative competences through the recognition of the limits of each profession, respect for the differences and the need for the comprehensive care30. The reported difficulties were academic standardization34, stereotyped conceptions among course students, distancing and the need for reciprocity between colleagues so that teamwork can be positive14. These obstacles are solved throughout the interaction, reaffirming the importance of shared learning and collaborative practice activities between students from different courses since, after the training, they will need to work together with other professions22.

Studies on RMS, created according to the principles of the SUS and the IPE, demonstrated the need to reflect on the work process of all actors involved in the provision of care. It shows the same positive results in relation to student satisfaction, patient-centered care, improvement in the quality of care and also the main effectiveness difficulties disclosed by the PET-Saúde program, such as difficulty in creating teams and exercising interprofessional work, preceptorship and service unpreparedness. These data reinforce the need to promote actions aimed at teaching-service integration, with the objective of collaborating in the training of health professionals aligned with the SUS10),(31),(33.

For the IPE implementation, the findings of this review are corroborated by research about the relevance of the work of teaching and health institutions to overcome bureaucracy5),(54, the availability and teaching load of the faculty5),(54; it is also the institutions’ responsibility to propose actions that motivate the work of the facilitator7),(54 and pedagogical training5),(54 to overcome uniprofessional training10),(33),(55, normative instructors and those with poor communication skills26),(43.

The studies involved in this scoping review on the IPE in the training processes of Brazilian students demonstrated advances in education and health management when they showed that the IPE was aligned with the principles and guidelines of the SUS, being understood as a powerful tool for transforming the training and qualification of care in the different training levels3),(21),(22),(24)-(33),(36)-(44. The IPE was also recognized by management as a complementary strategy to support other reforms in the country, such as the integration between universities, health services and the community21),(32),(33, in addition to being in line with the DCNs of undergraduate courses in the health areas and national policies for reorienting health education56.

The implementation of IPE during undergraduate school can be difficult; however, the articles analyzed in this review made recommendations27),(28),(29),(33),(40 that can allow facing these challenges3),(5),(10),(22),(26),(33)-(35),(38),(40)-(42. The successful implementation of the IPE requires a commitment from all those involved, both in the academic environment and in practice5),(57),(58),(59. Thus, managers, health services, and educational institutions should review their programs and curricula, seeking to recognize and take advantage of IPE opportunities to promote articulated actions in its implementation54. Among the actions suggested by the analyzed studies, the literature also highlights the promotion of an integrated curriculum and the promotion of the development of skills for collaborative practice5),(54),(57; accreditation of health services that share the same purpose5, expansion of the infrastructure54),(58; training and leadership of the faculty5),(55),(58 and of health workers for interprofessional work and collaborative practice54),(58.

Among the limitations of this review, it is necessary to mention the heterogeneity found in the reviewed studies, which may also have individual biases. The application of the presented results in different contexts can be difficult, as it portrays studies about the implementation of IPE in Brazil. However, there is the possibility of reproducing the method adopted in this scoping review to identify similarities or differences between countries regarding IPE.

It was understood that the IPE success depends on a cultural change in the exercise of health work by all the actors who participate in this process, so they can be agents of transformation, promoting better interpersonal relationships in the health service and promoting permanent education50.

CONCLUSION

When mapping IPE in the Brazilian context, it was observed that the studies are aligned with the SUS for the transformation of training and qualification of care, demonstrating the potential of IPE for learning and developing the skills required in the DCNs, despite the various challenges faced by the students, educators and management.

There has been an increase in HEIs that introduced the IPE to readjust their courses to the DCNs, aiming at transforming the training and qualification of care according to the health demands of the population, the guidelines and principles of the SUS.

The IPE is a teaching-service-community integration strategy that creates learning opportunities for students in the context of practice, providing the development of collaborative skills capable of strengthening and expanding knowledge about the SUS and promoting the direction of professional interest to the context of comprehensive health care.

Even though the Brazilian scenario of public policies and guidelines are favorable to the IPE, there are flaws regarding its implementation, which are perceived in all the analyzed studies; to overcome them, collaborative actions between HEIs, health services and managers are necessary, to discuss and jointly build curricula that promote interprofessional training following the guidelines of the DCNs, the integrality of care in line with the principles and guidelines of the SUS.

Finally, further studies are suggested on the weaknesses and strengths of IPE as a teaching strategy that promotes the integrality of care and the improvement of the Brazilian health care.

REFERENCES

1. Pan American Health Organization. Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage. 53rd Directing Council of PAHO, 66th Session the Regional Committee WHO for the Americas. Washington, DC: WHO; 2014 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/28276/CD53-5-e.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y . [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education & collabo-rative practice. Geneva: WHO; 2010 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf;jsessionid=19DE039ED79080263AA44132C638CBAF?sequence=1 [ Links ]

3. Silva JAM, Peduzzi M, Orchard C, Leonello VM. Interprofessional education and collabora-tive practice in primary health care. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(esp 2):15-23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420150000800003. [ Links ]

4. Miranda Neto MV, Leonello VM, Oliveira MAC. Multiprofessional residency in health: a doc-ument analysis of political pedagogical projects. Rev Bras Enferm. 2015;68(4):502-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167.2015680403i. [ Links ]

5. Ely LI, Toassi RFC. Integration among curricula in health professionals’ education: the pow-er of interprofessional education in undergraduate courses. Interface (Botucatu). 2018;22(supl 2):1563-75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0658. [ Links ]

6. Mikael SSE, Cassiani SHB, Silva FAM. The PAHO/WHO Regional Network of Interprofis-sional Health Education. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2017;25:e2866. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.0000.2866. [ Links ]

7. Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S, Davies N, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofissional education: BEME Guide Nº 39. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):656-68. doi: https://10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663. [ Links ]

8. Bahr H. Interprofessional education: the genesis of a global movement. London: Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education; 2015. [ Links ]

9. Rossit RAS, Freitas MAO, Batista SHSS, Batista NA. Constructing professional identity in Interprofessional Health Education as perceived by graduates. Interface (Botucatu) . 2018;22(supl 1):1399-410. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0184. [ Links ]

10. Arruda GMMS, Barreto ICHC, Pontes RJS, Loiola FA. Interprofessional education in health postgraduate: interprofissional pedagogical dimensions in a Family Health’s Multiprofessional Res-idency. Tempus. 2016;10(4):187-214. doi: https://doi.org/10.18569/tempus.v11i1.2179. [ Links ]

11. Brasil. Resolução CNE/CES nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014. Institui as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais dos Cursos de Graduação em Medicina e dá outras providências. Brasília: Ministério da Educação; 2014 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://normativasconselhos.mec.gov.br/normativa/view/CNE_RES_CNECESN32014.pdf?query=classificacao . [ Links ]

12. Freire Filho JR, Silva CBG, Costa MV A, Forster AC. Interprofessional education in the poli-cies of reorientation of professional training in health in Brazil. Saúde Debate. 2019;43(esp 1):86-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-11042019S107. [ Links ]

13. Brasil. Lei nº 11.129, de 30 de junho de 2005. Institui o Programa Nacional de Inclusão de Jovens - ProJovem; cria o Conselho Nacional da Juventude - CNJ e a Secretaria Nacional de Juventude; altera as Leis nºs 10.683, de 28 de maio de 2003, e 10.429, de 24 de abril de 2002; e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União; 2005 [aceso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/lei/l11129.htm . [ Links ]

14. Santos LC, Simonetti JP, Cyrino AP. Interprofessional education in the undergraduate Medi-cine and Nursing courses in primary health care practice: the students’ perspective. Interface (Bo-tucatu). 2018;22(suppl 2):1601-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0507. [ Links ]

15. Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update. “Scoping the scope” of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):147-50. doi: https://10.1093/pubmed/fdr015. [ Links ]

16. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-73. doi: https://10.7326/M18-0850. [ Links ]

17. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: update methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;5(52):546-53. doi: https://10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [ Links ]

18. O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Baxter L, Tricco AC, Straus S, et al. Advancing scoping study methodology: a web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:305. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1579-z. [ Links ]

19. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholth E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare. Phila-delphia: Lippincott Willians & Wilkin; 2011. [ Links ]

20. Hara CYN, Aredes NDA, Fonseca LMM, Silveira RCCP, Camargo RAA, Góes FSN. Clinical case in digital technology for nursing students’ learning: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;38:119-25. doi: https://10.1016/j.nedt.2015.12.002. [ Links ]

21. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. [ Links ]

22. Aguilar-da-Silva RH, Scapin LT, Batista NA. Evaluation of interprofessional education inun-dergraduarte health science: aspects of collaboration and teamwork. Avaliação. 2011;16(1):165-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-40772011000100009. [ Links ]

23. Capozzolo AA, Imbrizi JM, Liberman F, Mendes R. Experience, knowledge production and health education. Interface (Botucatu) . 2013;17(45):357-70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832013000200009. [ Links ]

24. Ellery AEL, Pontes RJS, Loiola FA. Common field of expertise of professionals in the Family Health Strategy in Brazil: a scenario construction. Physis. 2013;23(2):415-37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312013000200006. [ Links ]

25. Souto TS, Batista SH, Batista NA. The interprofessional education in educational psycholo-gy: student’s perspectives. Psicol Cienc Prof. 2014;34(1):32-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-98932014000100004. [ Links ]

26. Camara AMCS, Grosseman S, Pinho DLM. Interprofessional education in the PET-Health Program: perception of tutors. Interface (Botucatu) . 2015;19(sup 1):817-29. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622014.0940. [ Links ]

27. Cardoso AC, Corralo DJ, Krahl M, Alves LP. The incentive to practice of inter disciplinarity and multiprofessionalism: the University Extension as a strategy for interprofessional education. Rev ABENO. 2015;15(2):12-9 [acesso em 1º dez 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://revabeno.emnuvens.com.br/revabeno/article/view/93/161 . [ Links ]

28. Madruga LMS, Ribeiro KSQS, Freitas CHSM, Pérez IAB, Pessoa TRRF, Brito GEG. The PET-Family and the education of health professional: students’ perspectives. Interface (Botucatu) . 2015;19(supl1):805-16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622014.0161. [ Links ]

29. Forte FDS, Morais HGF, Rodrigues SAG, Santos JS, Oliveira PFA, Morais MST, et al. In-terprofessional education and the education through Work for Health Program “Stork Network”: leveraging changes in education. Interface (Botucatu) . 2016;20(58):787-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622015.0720. [ Links ]

30. Oliveira CM, Batista NA, Batista SHSS, Uchôa-Figueiredo LR. The writing of narratives and the development of collaborative practices for teamwork. Interface (Botucatu) . 2016;20(59):1005-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622015.0660. [ Links ]

31. Perego MG, Batista NA. Shared learning in the multiprofessional healthcare residency. Tempus . 2016;10(4):39-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18569/tempus.v11i1.2239. [ Links ]

32. Toassi RFC, Lewgoy AMB. Integrated health practices I: an innovative experience through inter-curricular integration and interdisciplinarity. Interface (Botucatu) . 2016;20(57):449-61. doi: https://10.1590/1807-57622015.0123. [ Links ]

33. Araújo TAM, Vasconcelos ACCP, Pessoa TRRF, Forte FDS. Multiprofessionality and inter-professionality in a hospital residence: preceptors and residents’ view. Interface (Botucatu) . 2017;21(62):601-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0295. [ Links ]

34. Azevedo AB, Pezzato LM, Mendes R. Interdisciplinary education in health and collective practices. Saúde Debate . 2017;41(113):647-57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-1104201711323. [ Links ]

35. Nuto SAS, Lima Junior FCM, Camara AMCS, Gonçalves CBC. An evaluation of health sci-ences students’ readiness for interprofessional learning. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2017;41(1):50-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v41n1RB20160018. [ Links ]

36. Rocha NB, Silva MC, Silva IRG, Lolli LF, Fujumaki M, Alves RN. Perceptions of learning about interprofessional discipline in Dentistry. Rev ABENO . 2017;17(3):41-54. doi: https://10.30979/rev.abeno.v18i4.598. [ Links ]

37. Albuquerque ERN, Santana MCCP, Rossit RAS. Multiprofessional residences in health as promoters of interprofessional training: perception nutritionists about collaborative practices. Deme-tra. 2018;13(3):605-19. doi: https://10.12957/demetra.2018.33495. [ Links ]

38. Arruda GMMS, Barreto ICHC, Ribeiro KG, Frota AC. The development of interprofessional collaboration in different contexts of multidisciplinary residency in family health. Interface (Botuca-tu). 2018;22(supl 1):1309-23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0859. [ Links ]

39. Capozzolo AA, Casetto SJ, Nicolau SM, Junqueira V, Gonçalves DC, Maximino VS. Inter-professional education and provision of care: analysis of an experience. Interface (Botucatu) . 2018;22(supl 2):1675-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0679. [ Links ]

40. Casanova IA, Batista NA, Moreno LR. Interprofessional education and shared practice in multiprofessional health residency programs. Interface (Botucatu) . 2018;22(supl 1):1325-37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0186. [ Links ]

41. Lago LPM, Matumoto S, Silva SS, Mestriner SF, Mishima SM. Analysis of professional prac-tices as a multiprofessional residency education tool. Interface (Botucatu) . 2018;22(supl 2):1625-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0687. [ Links ]

42. Oliveira VF, Bittencourt MF, Pinto IFN, Lucchetti ALG, Ezequiel OS, Lucchetti G. Compari-son of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning and the rate of contact among students from nine different healthcare courses. Nurse Educ Today . 2018;63:64-68. doi: https://10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.013. [ Links ]

43. Paro CA, Pinheiro R. Interprofessionality in undergraduate Collective Health courses: a study on different learning scenarios. Interface (Botucatu) . 2018;22(supl 2):1577-88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0838. [ Links ]

44. Prado FO, Rocha KS, Araújo DC, Cunha LC, Marques TC, Lyra DP. Evalution of student’s atitudes towardas pharmacist-physician collaboration in Brazil. Pharm Pract. 2018;16(4):1277. doi: http://10.18549/PharmPract.2018.04.1277. [ Links ]

45. Tompsen NN, Meireles E, Peduzzi M, Toassi RFC. Interprofessional education in under-graduation in dentistry: curricular experiences student availability. Rev Odontol UNESP. 2018;47(5):309-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-2577.08518. [ Links ]

46. World Healh Organization. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training: World Health Organization guidelines. WHO; 2013 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/93635/9789241506502_eng.pdf . [ Links ]

47. Barr H, Gray R, Helme M, Low H, Reeves S. Steering the development of interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(5):549-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1217686. [ Links ]

48. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. Interprofessional education gui-delines. Caipe; 2016 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.caipe.org/resources/international-publications-and-reports . [ Links ]

49. Ceccim RB, Cyrino EG. Formação profissional em saúde e protagonismo dos estudantes: percursos na formação pelo trabalho. In: Ceccim RB, Cyrino EG. O sistema de saúde e as práti-cas educativas na formação dos estudantes da área. Porto Alegre: Rede Unida; 2017 [acesso em 20 set 2018]. p. 4-26. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://historico.redeunida.org.br/editora/biblioteca-digital/serie-atencao-basica-e-educacao-na-saude/formacao-profissional-em-saude-e-protagonismo-dos-estudantes . [ Links ]

50. Hill E, Morehead E, Gurbutt D, Keeling J, Gordon M. 12 tips for developing inter-professional education (IPE) in healthcare [version 1]. MedEdPublish. 2019;8(69):1-13. doi: https://10.15694/mep.2019.000069.1. [ Links ]

51. Reeves S, Goldman J, Oandasan I. Key factors in planning and implementing interprofes-sional education in health care settings. J Allied Health. 2007;36(4):231-5. [ Links ]

52. G.C. Filies, J.M. Frantz. Student readiness for interprofessional learning at a local university in South Africa. Nurse Educ Today . 2021;104:104995. doi: https://10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104995. [ Links ]

53. El-Awaisi A, Anderson E, Barr H, Wilby KJ, Wilbur K, Bainbridge L. Important steps for in-troducing interprofessional education into health professional education. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2016;11(6):546-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.09.004. [ Links ]

54. Herath C, Zhou Y, Gan Y, Nakandawire N, Gong Y, Lu Z. A compartive study of interprofes-sional education in a global health care: a systematic review. Medicine. 2017;96(38):e7336. doi: https://10.1097/MD.0000000000007336. [ Links ]

55. Costa MV, Vilar MJ, de Azevedo GD, Reeves S. Interprofessional education as an ap-proach for reforming health professions education in Brazil: emerging findings. J Interprof Care . 2014 July;28(4):379-80. doi: https://10.3109/13561820.2013.870984. [ Links ]

56. Andrade MP, Ferreira FQ, Rodrigues VS, Bonafé UA, Félix MBR, Teixeira CP, et al. Paths to interprofessional education in health courses at an university of Minas Gerais. Res Soc Dev. 2021;10(9):e16510917926. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i9.17926. [ Links ]

57. Souza LRCV, Ávila MMM. Challenges and potentialities of interprofissionality in the contexto of the education through for health program. Res Soc Dev . 2021;10(9):e43109117618. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i4.14041. [ Links ]

58. Pinheiro GEW, Azambuja MS, Bonamigo WA. Facilities and difficulties experienced in Per-manent Health Education, in the Family Health Strategy. Saúde Debate . 2018;42(4):187-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-11042018S415. [ Links ]

59. Sunguya BF, Hinthong W, Jimba M, Yasuoka J. Interprofessional education for whom? Challenges and lessons learned from its implementation in developed countries and their applica-tion to developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96724. doi: https://10.1371/journal.pone.0096724. [ Links ]

Received: January 05, 2022; Accepted: June 17, 2022

texto em

texto em