Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versión impresa ISSN 0100-5502versión On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.46 no.4 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 15-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v46.4-20200562

REVIEW ARTICLE

Medical training in primary health care - a scoping review

1Centro Universitário da Fundação Assis Gurgacz, Cascavel, Paraná, Brazil.

2Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, Paraná, Brazil.

Introduction:

The inadequacies of medical schools in professional training regarding humanized care and aimed at the health needs of the population have been discussed for a long time. Several criticisms of the biomedical training model have been made and motivated several national and international entities and institutions to propose recommendations for a new training model, aimed mainly at the timely inclusion in Primary Health Care (PHC).

Objective:

To analyze how the inclusion of medical students in Primary Health Care during the undergraduate course occurs and the perception of different actors involved in this process.

Method:

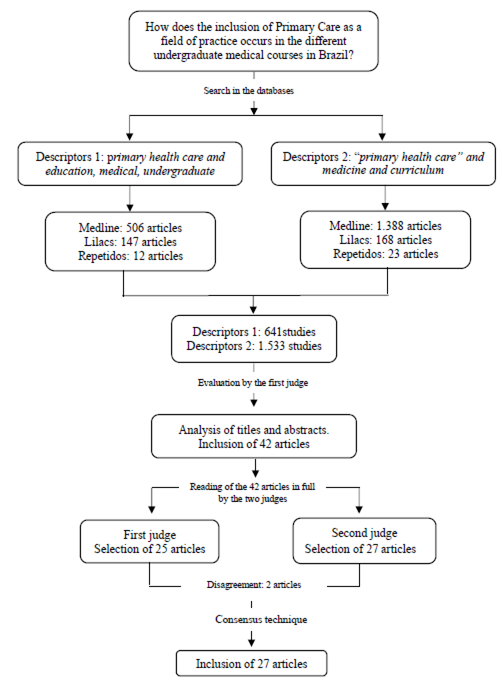

This is a scoping review. Two sets of descriptors were used, aggregated as follows: Primary Health Care and Undergraduate Medical Education and “Primary Health Care” and Curriculum and Medical. Initially, a total of 2,174 articles were selected, which, after the reading of the title and abstract, was reduced to 42 and later, after being read in full, 27 studies were listed for the analysis.

Results:

Most studies were published (70%) after 2015, 52% in the same journal and as an experience report. The National Curriculum Guidelines appeared as the main motivator for change in 82.3% of the articles; 100% have timely inclusion, with 76.5% occurring as early as in the first semester; 47.1% entered the internship throughout eight semesters, but only 29.4% report the inclusion during the internship. Regarding the learning objectives, it was verified that it meets the graduates’ profile and that recommended by the guidelines. The perception of students and teachers points to the role of the internship in PHC as an important training space for the development of skills and abilities recommended by the guidelines. Among the negative aspects are the lack of structure in the units, the lack of trained professionals and unprepared tutors for teaching at this level of care, and precarious arrangements between the institution and departments.

Conclusion:

It can be seen in the assessed articles that undergraduate medical training meets the recommendations of the 2014 National Curriculum Guidelines, of international authors and experience reports; however, it is necessary to advance in relation to the teaching and student culture that overvalue the specialization, in teacher training and teaching-service integration.

Keywords: Primary Health Care; Curriculum; Medicine; Medical, Education, Undergraduate

Introdução:

Inadequações das escolas médicas na formação profissional, no que concerne a um atendimento humanizado e às necessidades de saúde da população, há muito vêm sendo discutidas. Diversas críticas ao modelo de formação biomédico têm sido feitas e motivaram várias entidades e instituições nacionais e internacionais a propor recomendações para um novo modelo de formação voltado principalmente para a inserção oportuna na atenção primária à saúde (APS).

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivos analisar como ocorre a inserção dos acadêmicos de Medicina na APS durante a graduação e verificar a percepção dos diferentes atores envolvidos sobre esse processo.

Método:

Trata-se de uma scoping review. Foram utilizados dois conjuntos de descritores agregados da seguinte forma: atenção primária à saúde and educação de graduação em Medicina e atenção primária à saúde and currículo and médico. Inicialmente, selecionaram-se 2.174 artigos. Após a leitura de título e resumo, houve a seleção de 42 artigos. Por fim, depois da leitura na íntegra, elencaram-se 27 estudos para análise.

Resultado:

Os estudos foram publicados em sua maioria (70%) após 2015, 52% em um mesmo periódico e como relato de experiência. As Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais (DCN) apareceram como principal motivador para mudança em 82,3% dos artigos; 100% possuem inserção oportuna, sendo 76,5% já no primeiro semestre; 47,1% têm inserção do estágio ao longo de oito semestres; e apenas 29,4% referem inserção no internato. Em relação aos objetivos do aprendizado, verifica-se que este vai ao encontro do perfil de egresso e do recomendado pelas DCN. A percepção dos discentes e docentes aponta o papel do estágio em APS como espaço de formação importante para o desenvolvimento de competências e habilidades preconizadas pelas DCN. Entre os aspectos negativos, destacaram-se a falta de estrutura das unidades, a ausência de profissionais com formação, preceptores despreparados para o ensino nesse nível de atenção e convênios precários entre instituição e secretarias.

Conclusão:

Percebe-se, nos artigos estudados, que a formação médica na graduação atende ao preconizado nas DCN de 2014, em autores e experiências internacionais, porém é necessário avançar em relação à cultura de docentes e discentes que supervalorizam a especialização, na formação dos professores e na integração ensino-serviço.

Palavras-chave: Atenção Primária à Saúde; Currículo; Medicina; Educação de Graduação em Medicina

INTRODUCTION

Inadequacies in the training of medical professionals considering humanized care and focused on the health needs of the population have long been discussed1. The medical training model in Brazil was influenced by the recommendations proposed by Abraham Flexner in his report, published in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century2),(3, imprinting mechanistic, biologicist, individualizing and specialization characteristics in medicine4. However, it has been acknowledged that, in order to provide comprehensive care, the medical professional needs to better understand the determinants of the health-disease process, in addition to the biological aspects of people’s illness. It also requires that the social and psychological context of users and population be considered, that is, it requires the broadening of one’s view5, which demands changes in their training.

In an attempt to propose changes to the current medical training, different international entities have prepared recommendations, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges (1981) with the Panel for the General Professional Education of the Physician and College Preparation for Medicine; the World Federation for Medical Education (1988) with the Edinburgh Declaration; and the Robert-Wood Johnson Foundation. In common, all documents reinforce the importance of including aspects of health promotion and prevention, community integration and expanding the practice environment beyond the hospital, with the inclusion of students into local health systems6)-(8.

In the perspective of reaching the objective “Health for All in the Year 2000”, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified Primary Health Care (PHC) as a central strategy for the organization of Health Systems and recommends that a good part of the undergraduate medical practice take place inside the Health System and, therefore, also have PHC as a practice scenario6.

In Brazil, since the 1980s, some projects and programs have been organized aiming to attain changes in medical training, such as the Assistance Teaching Integration Project (IDA, Integração Docente Assistencial), and the Promed, Pró-Saúde, and Pet Saúde Programs, among others. All these initiatives had as a common axis the restructuring of the curriculum of medical courses, in the schools where they were developed, aiming to overcome the biomedical model and to include students into new practice scenarios3.

These strategies also had the capacity to influence, in the national scenario, the publication of new National Curriculum Guidelines (DCNs, Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais) for Medical Courses, with the first being published in 2001 and the second in 2014. The guidelines propose the reformulation of the curricula, including new practice scenarios and other strategies, such as active teaching-learning methodologies aiming to generate actual changes in the profile of graduate physicians3.

Gomes et al. (2012)9 defend the necessary changes in medical education and recognize the importance of curricular guidelines that point in this direction. They recognize that, although this scenario has been gradually changing in the 21st century, they warn of the risk that the changes will only affect methodological issues, and there are still doubts about the best ways to enable successful inclusion in PHC.

Considering the above, as well as the publication of a new DCN in 2014, this literature review study was carried out with the objective of analyzing how the inclusion of medical students in Primary Health Care occurs during undergraduate school and the perception of the different actors involved on this process.

METHODS

For data collection, the “scoping review” or “scoping study” was used as a tool, an approach that has been increasingly used to analyze evidence in health research. This modality of literature review was proposed by researchers Hilary Arksey and Lisa O’Malley10 in 2005, and allows assessing the extent, scope and nature of research activity, summarizing and disseminating study results, as well as identifying research gaps in the existing literature10. This study followed the following steps: (1) identification of the research question; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data mapping; (5) comparison, summary and reporting of results.

The problem that guided the development of this research was the need to know the content in the literature on medical training in relation to the inclusion of students in Primary Care, which motivated the implementation of the PHC practice scenario, the teachers’ and students’ perceptions and the challenges for the changes in the curricular structure. Therefore, the following research question was defined: “How does the inclusion of Primary Care as a field of practice occurs in the different undergraduate medical courses in Brazil?”

The following inclusion criteria were used for the study: original articles that had free access abstracts; published in Portuguese, English and/or Spanish; published in the period from 2001 to 2020, considering that the first Curricular Guideline for the Medical Course was published in 2001. Books or book chapters, monographs, theses, dissertations, official documents and review articles were excluded from the research, as well as articles that did not portray training in Brazilian universities.

The literature search was carried out in the following databases: Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde - Lilacs and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online - Medline. The website of the Virtual Health Library (VHL) was used to search the LILACS database and PubMed for the Medline database.

The following Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) were used: Atenção Primária à Saúde; Educação de Graduação em Medicina; Educação Médica; Currículo; Primary Health Care; Education, Medical, Undergraduate; Education, Medicine; Curriculum.

For the search in the databases, the descriptors were aggregated using the Boolean operator AND as follows: “Atenção Primária à Saúde” and “Educação de Graduação em Medicina”; “Primary Health Care” and “Education, Medical, Undergraduate”, “Atenção Primária à Saúde” and Currículo and Médico and “Primary Health Care” and Medicine and Curriculum. The search was carried out during the month of November 2020.

Study selection was performed based on the analysis by two judges (the standard examiner is the main author of the study and examiner I, the second author of the study), according to the guiding question and the previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies found during the search using the descriptors were initially evaluated by the standard examiner through the analysis of titles and abstracts.

Figure 1 depicts the methodological route, detailing the search results by descriptors and by databases, as well as the results of the selection of the articles included in the study, based on the analysis of the judges.

RESULTS

Data mapping using data from the studies was performed and the extracted information comprised three analysis groups, with the first being: article references, with place and year of publication, article title, authors, place of publication, objectives and methodology. The second analysis group included medical training for PHC and the third included the perception of the different actors involved on the inclusion in PHC internships. Subsequently, the results and conclusions were compared and discussed for a more in-depth analysis of the selected studies.

Characterization of the studies included in the Scoping Review

This section shows some characteristics of the analyzed studies, since knowing the context in which the studies were produced can help in understanding the results found in this analysis. Chart 1 shows the summary of selected articles.

Chart 1 Description of the studies used in the scoping review

| Year/authors | Journal | Title | Place | Method | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pereira et al. (2009)11 | Mundo saúde | Integração academia, serviço e comunidade: um relato de experiência do curso de graduação em medicina na atenção básica no município de São Paulo | São Paulo/SP | Experience report | Describe some experiences over three semesters in which the IASC was implemented and increasingly improved jointly by the actors involved in the process. |

| Anjos et al. (2010)12 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | “Vivendo o SUS”: uma experiência prática no cenário da atenção básica | Sorocaba/SP | Experience report | To present the project “Vivendo o SUS” . |

| Martines e Machado (2010)13 | Mundo saúde | Instrumentalização do aluno de Medicina para o cuidado de pessoas na Estratégia Saúde da Família: o relacionamento interpessoal profissional | São Paulo/SP | Experience report | To describe experiences related to the training of undergraduate medical students at Centro Universitário São Camilo, specifically related to the instrumentalization process regarding the interprofessional relationships. |

| Ruiz et al. (2010)14 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Internato regional e formação médica: percepção da primeira turma pós-reforma curricular | Santa Maria/RS | Quali-quantitative | Obtain the perception of students from the first group to attend the Regional Internship about the impact of this model on their academic and professional training. |

| Costa et al. (2012)15 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Formação médica na estratégia de saúde da família: percepções discentes | Teresópolis/RJ | Qualitative | To present the perception of medical students in the teaching-learning scenarios of Primary Health Care. |

| Neumann e Miranda (2012)16 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Ensino de atenção primária à saúde na graduação: fatores que influenciam a satisfação do aluno | Porto Alegre /RS | Quali-quantitative | To evaluate whether the changes implemented in the medical curriculum related to the MASC discipline - change of semester and inclusion in PET-Saúde - resulted in differences regarding the students’ perception of the discipline. |

| Makabe e Maia (2014)17 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Reflexão discente sobre a futura prática médica através da integração com a equipe de saúde da família na graduação | São Paulo/SP | Quantitative | To study, from the point of view of medical students from Universidade da Cidade de São Paulo, the influence of contact with the community in a Basic Health Unit of the Family Health Program on the humanization of these students’ future professional practice. |

| Souza et al. (2014)18 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | O Universitário Transformador na comunidade: a experiência da USS | Vassouras /RJ | Experience report | To disclose the experience of the USS medical course with the inclusion of students’ activities in the community in the early years, describing the adopted methodology and the pedagogical and social developments provided by this innovation in the teaching-learning process in the teaching of Medicine. |

| Bezerra et al. (2015)19 | ABCS health sci | A dor e a delícia do internato de atenção primária em saúde: desafios e tensões | Santo André/ SP | Quantitative | To identify the students’ perception regarding the insertion of CAPS in the medical internship. |

| Gomes et al. (2015)20 | Saúde Redes | Currículo de medicina na Universidade Federal da Paraíba: reflexões sobre uma experiência modular integrada com ênfase na Atenção Básica | João Pessoa/PB | Experience report | Describe the implementation of the Practical - Integrative Module of the UFPB PPC. |

| Almeida et al. (2016)21 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Trabalho de Campo Supervisionado II: uma experiência curricular de inserção na Atenção Primária à Saúde | Niterói / RJ | Experience report | To systematize, describe and analyze the contributions of the systematic inclusion in PHC as an instrument of change in medical training, in the context of Supervised Field Work II, from the perspective of students and preceptors, aiming to debate and question the potentials of PHC as a health training scenario. |

| Silvestre et al. (2016)22 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Avaliação Discente de um Internato Médico em Atenção Primária à Saúde | Florianópolis / SC | Quali-quantitative | To analyze the evaluation of USFC medical students on the stages of the Internship in Community Interaction (Primary Health Care) in the ninth and tenth semesters, based on the curricular change carried out in 2012. |

| Melo et al. (2017)23 | Rev. Ciênc. Plur | Uma experiência de integração ensino, serviço e comunidade de alunos do curso de graduação em medicina na atenção básica no município de Maceió-AL, Brasil | Maceió / AL | Experience report | To present the relevance of the discipline in medical training as a mandatory element of the curricular structure. |

| Oliveira et al. (2017)24 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Vivência integrada na comunidade: inserção longitudinal no Sistema de Saúde como estratégia de formação médica | Natal / RN | Experience report | To report the experience about the VIC module, a mandatory curricular component developed at EMCM - UFRN. |

| Silva et al. (2017)25 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Medicina de Família do Primeiro ao Sexto Ano da Graduação Médica: Considerações sobre uma Proposta Educacional de Integração Curricular Escola-Serviço | São Paulo/SP | Experience report | To describe and analyze a model of inclusion of PHC and Family and Community Medicine (FCM) from the first to the last semester in the medical course of Santa Marcelina School of Medicine (FASM) in the city of São Paulo, the challenges of the teaching-management articulation and the actions that help to face them. |

| Teófilo et al. (2017)26 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Apostas de mudança na educação médica: trajetórias de uma escola de medicina | Sobral / CE | Qualitative | To know the teaching-learning practices, institutional arrangements and the participation of different actors in a medical undergraduate course in the city of Sobral - CE. |

| Poles et al. (2018)27 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Percepção dos Internos e Recém-Egressos do Curso de Medicina da PUC-SP sobre Sua Formação para Atuar na Atenção Primária à Saúde | São Paulo/SP | Quali-quantitative | To assess whether the medical student at the end of the course and the recent graduate consider themselves prepared to work in primary health care, identifying the positive and negative points of their training in order to propose the necessary adjustments to contribute to the improvement of the medical course and training of graduates from FCMS at PUC/SP |

| Vieira et al. (2018)28 | Saúde Debate | A graduação em medicina no Brasil ante os desafios da formação para a Atenção Primária à Saúde | Brazil | Quali-quantitative | To identify elements of the medical training in Brazil, analyzing their closeness to the assumptions of professional practice in Primary Health Care and the National Curriculum Guidelines of 2014. |

| Coelho et al. (2019)29 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | A Formação-Intervenção na Atenção Primária: uma Aposta Pedagógica na Educação Médica | Recife / PE | Experience report | To describe the experience of two modules of Fundamentals of Primary Care I and II (FABS I and II) offered to students at a public university in Northeastern Brazil. |

| Ferreira et al. (2019)30 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Novas Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para os cursos de Medicina: oportunidades para ressignificar a formação | Fortaleza / CE | Action research | To carry out a critical-reflective analysis of the restructuring of the curricular matrix for a medical course. |

| Parma et al. (2019)31 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Percepção dos Profissionais de Saúde em relação à Integração do Ensino de Estudantes de Medicina nas Unidades de Saúde da Família | Votuporanga/SP | Qualitative | To understand the perception of professionals from the Family Health Units (FHUs) regarding the inclusion of medical students in these services and interpret the consequences for the service, the community and medical training. |

| Pedroso et al. (2019)32 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | A Educação Baseada na Comunidade no Ensino Médico na Uniceplac (2016) e os Desafios para o Futuro | Distrito Federal/DF | Qualitative | To raise the significance and meanings that teachers attribute to Community-Based Education in the current curricular matrix in UNICEPLAC medical education in 2016 and identify possibilities for improving teaching at the institution in line with the current national guidelines. |

| Peixoto et al. (2019)33 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Formação médica na Atenção Primária à Saúde: experiência com múltiplas abordagens nas práticas de integração ensino, serviço e comunidade | Feira de Santana/BA | Experience report | To discuss medical training in an institution in the interior of the state of Bahia, based on PHC and the National Curriculum Guidelines for medical courses. |

| Rezende et al. (2019)34 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Percepção discente e docente sobre o desenvolvimento curricular na atenção primária após Diretrizes Curriculares de 2014 | Goiânia/GO | Qualitative | To evaluate the perceptions of students and teachers about the development of a new curriculum for the medical course of a Federal University in the Midwest region of Brazil after the new National Curriculum Guidelines of 2014 regarding teaching in Primary Health Care (PHC). |

| Rezende et al. (2019)35 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Análise documental do projeto pedagógico de um curso de Medicina e o ensino na Atenção Primária à Saúde | Goiânia/GO | Case study | To analyze and compare the PPC of the medical course at UFG according to the determinants of the 2014 DCNs and the document Guidelines for Teaching in Primary Health Care in Undergraduate Medical School |

| Coelho et al. (2020)36 | Interface comun. saúde educ | Atenção Primária à Saúde na perspectiva da formação do profissional médico | Fortaleza / CE | Qualitative | To analyze, from the perspective of medical internship students, Primary Health Care as a learning environment. |

| Lima et al. (2020)37 | Rev. bras. educ. méd | Análise do Internato em Medicina da Família e Comunidade de uma Universidade Pública de Fortaleza - CE na Perspectiva do Discente | Fortaleza / CE | Quali-quantitative | To analyze the internship in Family and Community Medicine (FCM) at a public university in Fortaleza-CE from the student’s perspective. |

Source: prepared by the authors, 2020.

The articles were selected from the year 2001 onwards, but it was found that in the first eight years of the selected period no studies were published on the topic of interest. As of 2009, there was at least one article published and the year with the highest number of publications was 2019, with seven articles.

Regarding the journals in which the articles were published, it was observed that the 27 articles were published in eight different journals, with Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica being responsible for more than half of the publications.

The studies were carried out at universities in several regions of the country. The Southeast region had the highest number of studies, followed by the Northeast region and then the South and Midwest regions. One of the studies assessed universities in several states and the North region did not publish any studies. Regarding the states of the institutions responsible for the publications, São Paulo was the one with the highest number of published articles (eight).

Regarding the administration of the assessed institutions, 13 were public, of which 12 were federal and one was a state institution; 11 were private, one was public-private and two analyzed more than one institution in the same article.

Most of the studies used the experience report as their methodology. There were also quali-quantitative, qualitative, quantitative, case study and action research studies. Most (15) articles addressed the perception/assessment of students, teachers or other actors about internships in PHC and 12 of them addressed the process of implementing an internship in Primary Health Care in the curriculum of the medical course. Among the articles that addressed the perception of students, teachers or service professionals, in five of them it was also possible to obtain information related to the curricular structure of the course, thus being part of the two analysis groups.

Medical training for Primary Care

To evaluate training for Primary Care, the 17 articles that addressed this topic were analyzed.

During the presentation of the driving motive for the curricular change, the DCN appeared in 14 publications, in addition to the Promed in one, the Pet-saúde in one and both the DCN and Pet-Saúde in another one.

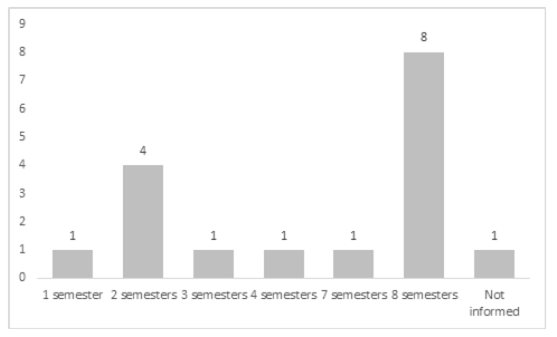

Among the analyzed articles, 12 of them reported that the students attend the PHC internships as early as in the first semester of the course. The distribution of the semesters during which the students attend the PHC internships is shown in table 1.

Table 1 Semesters during which students attend the PHC internships

| Semester | % | |

|---|---|---|

| First to Eighth semesters | 8 | 47.1 |

| First and Second semesters | 2 | 11.7 |

| Third and Fourth semesters | 2 | 11.7 |

| First or Third semester | 1 | 5.9 |

| First to Third semesters | 1 | 5.9 |

| First and Third semesters | 1 | 5.9 |

| Second to Eighth semesters | 1 | 5.9 |

| Not informed | 1 | 5.9 |

Source: prepared by the authors, 2020.

In 15 medical courses, this inclusion takes place in the Basic Health Unit, and in another, in addition to the Basic Health Units, it also includes Secondary and Tertiary Care services, whereas another one does not clearly mention the place of inclusion. The duration of the internship is shown in Figure 2.

Source: prepared by the authors, 2020.

Figure 2 Duration time of inclusion of students in the PHC internship

The articles reported that PHC inclusion during the internship occurred in only five courses, whereas there is no record of this information in the remaining twelve.

Regarding why students should attend practical internships in Primary Care, several justifications appear, among them: generalist training, critical and reflective training, humanized care, care based on people, families and community, and teamwork, among others, which are detailed in Chart 2.

Chart 2 Student learning objectives with PHC inclusion in selected articles

| What does the course expect in terms of student development with PHC inclusion? |

|---|

| • Getting in touch with the complexity of the person-centered practice, with the obligation to work in a team and network, doing longitudinal follow-up, allows the student to acquire essential skills for the exercise of the profession. |

| • At the end of the course, the student will be able to: perform community diagnosis, perform a medical consultation using the person-centered clinical method, perform the family approach, work as a team, recognize the difficulties faced by the health system users and propose actions to mitigate them, offer integral and humanistic care, understand people in their life, family, social and environmental context. |

| • To develop and qualify in generalist medical skills and attitudes |

| • To develop the preparation and skills necessary to solve real-life problems, work in multidisciplinary teams, valuing each FHS professional, develop critical and reflective capacity and promote comprehensive care to the population, focusing not only on the disease, but on the health of the entire human being. |

| • Training of a general practitioner, therefore, the experience of all students at all levels of SUS care, but with an emphasis on family health. |

| • Train a physician who understands the expanded concept of health and knows how to embrace and establish accountability bonds, in the coordination of the necessary actions to improve the quality of life of people, families and the community. |

| • To train physicians with a generalist, humanistic, critical and reflective performance, capable of acting in the health-disease process at its different levels of care, keeping coherence with the epidemiological profile of the population, based on ethical principles, aiming to promote the integral health of the human being. |

| • To train a general practitioner more suited to the challenges of modern society. |

| • To encourage undergraduate students to understand the determinants and relationships of diseases with people’s way of life and work. Care based on the health of individuals, families and community. To understand the difficulties and possibilities of combined health practices, experiencing the real context of the SUS. |

| • To identify and act on real-life problems, assuming increasing responsibilities as an agent providing care compatible with their degree of autonomy. Comprehensive and humanized actions to solve the population’s health problems. |

| • To interact and connect the university with the health services and the community and the medical student in the daily life of the FHUs, create the opportunity to know models of health care for a population, health planning, enable the observation of the work of a FHP team, at home and in the community, knowing people’s health needs, raising awareness for the development of educational and pedagogical practices that facilitate the sharing of knowledge and information |

| • To enable the understanding of the process of building collective health knowledge, correlating it with the performance of professionals in the practical field; conceptualize important aspects of the SUS and their applicability in the internship practice. |

| • To enable a humanistic and ethical critical training. To incorporate knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary for the construction of the person-centered medical practice and sensitive to the realities of the health system. |

Source: Prepared by the authors, 2020.

The perception of the different actors involved on the inclusion in the PHC internships

As described in Chart 2, of the 15 articles that discussed the perception regarding the inclusion in Primary Health Care internships, 12 of them described the students’ perception, one the teachers’ perception, another the students’ and teachers’ perceptions and one article described the service preceptors’ perception.

The following appear as positive aspects about the inclusion in Primary Care, in the students’ view: timely inclusion, bringing more security by allowing the contextualization of theory with real-life situations (theoretical-practical learning), contact with the patient since the early years, development of clinical skills, understanding the care of the individual in their family and social context, longitudinality, experience in health education, humanistic aspects, learning about the doctor-patient relationship, comprehensive approach to care, with health promotion, protection and rehabilitation actions, social determination of the health-disease process, teamwork, role of PHC in health care networks, humanization and development of self-confidence.

The negative aspects perceived by the students are: distance and cost to travel to the health units, lack of physical structure of the health units, lack of time to discuss cases, urban violence, lack of integration of the discipline with the other ones, lack of transversality, lack of teachers with specific training or preceptors’ deficient training, absence of preceptors in some places, excessive theoretical classes and failure of health care networks.

Among the teachers, the positive aspects were the inclusion since the first semesters, with diversification of practice scenarios, development of skills and competences as recommended by the DCNs. Among what was negatively evaluated is the lack of knowledge of teachers about generalist training, lack of teachers with specific training, the fact that some teachers understand the timely inclusion as clinical care and do not provide opportunities for other approaches, lack of physical structure in the units, lack of integration of the discipline with others of the curriculum, lack of appreciation of the SUS and also students and teachers with a focus on the specialty.

The preceptors understand that the students’ presence was a positive aspect, as their presence encourages the permanent training of professionals and the team, there is an improvement in interprofessional work and the strengthening of health education groups. As negative aspects, the lack of respect by some students, the population’s initial embarrassment and the turnover of students, which hinders the establishment of bonds.

The perception of the different actors involved on the inclusion in the PHC internships

As described in Chart 2, of the 15 articles that discussed the perception regarding the inclusion in Primary Health Care internships, 12 of them described the students’ perception, one the teachers’ perception, another the students’ and teachers’ perceptions and one article described the service preceptors’ perception.

The following appear as positive aspects about the inclusion in Primary Care, in the students’ view: timely inclusion, bringing more security by allowing the contextualization of theory with real-life situations (theoretical-practical learning), contact with the patient since the early years, development of clinical skills, understanding the care of the individual in their family and social context, longitudinality, experience in health education, humanistic aspects, learning about the doctor-patient relationship, comprehensive approach to care, with health promotion, protection and rehabilitation actions, social determination of the health-disease process, teamwork, role of PHC in health care networks, humanization and development of self-confidence.

The negative aspects perceived by the students are: distance and cost to travel to the health units, lack of physical structure of the health units, lack of time to discuss cases, urban violence, lack of integration of the discipline with the other ones, lack of transversality, lack of teachers with specific training or preceptors’ deficient training, absence of preceptors in some places, excessive theoretical classes and failure of health care networks.

Among the teachers, the positive aspects were the inclusion since the first semesters, with diversification of practice scenarios, development of skills and competences as recommended by the DCNs. Among what was negatively evaluated is the lack of knowledge of teachers about generalist training, lack of teachers with specific training, the fact that some teachers understand the timely inclusion as clinical care and do not provide opportunities for other approaches, lack of physical structure in the units, lack of integration of the discipline with others of the curriculum, lack of appreciation of the SUS and also students and teachers with a focus on the specialty.

The preceptors understand that the students’ presence was a positive aspect, as their presence encourages the permanent training of professionals and the team, there is an improvement in interprofessional work and the strengthening of health education groups. As negative aspects, the lack of respect by some students, the population’s initial embarrassment and the turnover of students, which hinders the establishment of bonds.

DISCUSSION

After the review was carried out, it was observed there was a lack of studies at the national level with a more robust methodology, especially controlled studies comparing inclusion and non-inclusion in PHC with medical training outcomes. In other words, most of the selected studies comprise experience reports and this may lead to result fragility, as well as limit the understanding of how the inclusion of Primary Care is taking place as a field of practice in the different undergraduate medical courses in Brazil - the question chosen to be answered by this scoping review. It is also recognized, as a limitation of the present study, the review methodology used, due to the fact that selection bias can occur in this type of study.

Despite the widespread importance of strategies such as the Promed and Pet-Saúde, for the implementation of changes in medical training, it was found that most of the selected studies recognize the DCN as a driver of curricular changes. Another result that reinforces this finding is the fact that most articles were published between 2015 and 2020, after the publication of the second curricular guideline.

The DCNs point out that one should:

Art. 29. VI - include the student in the health service networks, considered as a learning space, since the initial years and throughout the Undergraduate Medical course. VII - use different teaching-learning scenarios, especially the health units of the three levels of care. VIII - provide the student with active interaction with users and health professionals, since the beginning of their training38.

If we analyze the fact that the articles above deal with curricula whose influence on structuring consisted primarily of the DCN 2014, it can be observed that they meet what is described in these topics.

Demarzo et al.39, describe the guidelines for the teaching of Primary Care in Undergraduate Medical Schools, recommending that the internship should occur longitudinally throughout the course, with increasing complexity and whose activities should be included since the first year, also corroborating the findings of this study

The development of these activities at the beginning of the undergraduate course allows students to have the opportunity to integrate themselves early into the daily life of a community, in its different contexts and to face theoretical-practical aspects with an activity based on the experience of teaching-service integration40.

The inclusion of the medical student in primary health care must occur in an integrated manner with health systems. In a study carried out with 108 Brazilian medical schools, it was evident that they also followed the recommendations of the DCNs and established teaching-service integration with agreements with local management, aiming at promoting integration and interdisciplinarity in curricular development and seeking changes in their curricular matrix and methodologies41.

A study carried out in 259 medical schools in Europe found that 81% of them also had a PHC internship. In another study, a questionnaire applied in 40 medical schools in Europe identified that 80% of these schools implemented a timely clinical exposure as early as in the first year, as shown in this study; however, in Europe this inclusion occurred as of the end of the first semester and not right at the beginning of the course as observed. The inclusion period varied from two weeks to two years42, a shorter time than that described in the researched articles. In another study, carried out in twenty-eight schools in the United Kingdom, it was found that 50% of the schools had this inclusion throughout all five years of the course and 25% in two or three years16, which is more similar to what was identified in this article.

Bazak et al.42 reported that the inclusion in PHC would aim at several aspects related to medical practice, in addition to the introduction of medical skills such as anamnesis and physical examination. A study of 28 schools in the United Kingdom that evaluated documents related to internships in PHC, showed as training objectives consultation and communication skills, teamwork and individual development, diagnosis and treatment, promotion, and prevention43. Another study, also carried out in the UK with undergraduate students, highlighted that the integration between theory and practice, the students’ motivation to study for career goals, the practice of skills and clinical assessment, communication development, consultation skills, working with patients, understanding the Health System are benefits of timely curricular inclusion44. These objectives are very similar to those found in the articles depicted in Chart 2.

Harvard educators developed a curriculum content for PHC training with the following characteristics: longitudinality, generalist training, central coordination of care, communication skills for building therapeutic alliance, knowledge about acute and chronic conditions, care in the different phases of the life cycles, including health promotion and prevention actions, addressing the most prevalent mental disorders and changes in lifestyle habits, practice scenarios in outpatient clinics of the health system, teamwork and health determinants45. All these characteristics were also reported in the selected studies, except for actions related to mental health care.

The DCNs of 201438 present all the objectives found in this review, such as learning objectives for medical students, and some of those described objectives are part of the characteristics of the graduate’s profile. Demarzo et al.39 also mention individual, family and community skills and competences as a justification for training in PHC.

It is verified that the positive aspects that appear in the teachers’ evaluation are also perceived by the students, although there are many more aspects evaluated by the latter as positive. In relation to the negative aspects, the lack of teacher training and the lack of infrastructure of the units, perceived by both students and teachers, are highlighted.

The DCNs38 of 2014 bring as important aspects of medical training all the items identified as positive points of medical training pointed out by students and teachers, demonstrating how much the PHC scenario has been used by the assessed institutions with the objective of adapting training to the profile expected by the DCNs.

An article that analyzes the experience of a Brazilian public institution shows that internship teachers do not know Primary Care and that students should be “specialists”, corroborating some of the negative results pointed out by students and teachers in the analyzed studies46. This perception appears as a negative aspect, demonstrating that the training of teachers, whether they are service preceptors or teachers at educational institutions, is one of the problems that need to be analyzed in PHC training.

In a survey carried out in Spanish medical schools with students in the 1st, 3rd and 5th years, it was found that 87% of the students believe that there are sufficient justifications for theoretical-practical learning in Medicine and Community, which plays an essential social role. However, less than 20% consider it to have similar status to other medical specialties47. Another study carried out in Genova and Lausanne showed that learning in PHC has a positive influence on the students’ concept of medical work at this level48. Students from Athens, who attended a clinical practice internship at PHC, evaluated that there was a significant improvement in their clinical skills, physical examination and interest in specializing in PHC49. Similar results were found regarding the students’ perception in the articles included in this review.

The participation of students in PHC should aim at creating bonds with the community and actions to be developed on the community demands identified by the residents and health professionals, on how to deal with users. This inclusion should promote benefits to the team and the community, not harming or complicating the existing work process9. It can be observed that these aspects appear in the students’ analysis, but mainly in the evaluation of the service preceptors, demonstrating it remains a challenge to be overcome in the teaching-service integration in Brazil.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering the methodology used in this review, it is known that a selection bias can occur. Another limitation of the study is due to the fact that the degree of evidence of the selected studies was not analyzed and, considering that most of them comprise experience reports, this may lead to result fragility. More studies, with better levels of scientific evidence, are shown to be necessary.

As discussed by different groups of scholars, as well as described in several articles, both national and international ones, training in PHC plays an important role in the transformation of medical training, especially the changing of the biomedical model into a model in which the social determination of the health-disease process and the individual’s social, family and work contexts are included in the care process and, consequently, in the training process of medical students.

To think of a doctor with humanistic, critical and reflective training, with skills and competences that allow them to act from the health promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation actions, capable of using tools of individual, family and community approach, demands their inclusion in practice scenarios in which the closest contact with the individual and their context occurs. This scenario is undoubtedly the PHC.

Analyzing the selected articles, it can be observed that much has already been done in terms of curricular adequacy to the 2014 DCNs and the training that contemplates the aforementioned changes, but much remains to be done, considering that the number of schools that appear in the study is much lower than the total number of Brazilian medical schools, a limiting factor for this analysis.

Also, when discussing the perception of the different actors, it can be observed that the importance of a timely inclusion in PHC is acknowledged in most cases, with PCH being an important training space for the physician and that the teaching-service integration, with the approximation of theory and practice undoubtedly play an important role in the quality of training. However, the lack of teacher training, lack of physical structure in the Health Units, lack of integration of the basic cycle with the clinical one, lack of appreciation of the SUS, in addition to the prioritization of the specialization areas by the students and many teachers, as well as the curricular structure that predisposes the training of specialists have also been recorded.

Therefore, the DCNs for the medical course represent a milestone for the change in the hospital-centered and biomedical model of medical education; significantly influenced a number of medical schools, but much remains to be improved, if we really want to train doctors with the profile that Brazil and that national and international leaders understand as necessary.

Thinking about strategies to improve the teaching-service integration, regarding better established agreements between teaching institutions and health departments, as well as tools to qualify teachers for teaching in PHC seem to be important steps to be established.

REFERENCES

1. Itikawa FA, Afonso DH, Rodrigues RD, Guimaraes MAM. Implantação de uma nova disciplina à luz das diretrizes curriculares no curso de graduação em Medicina da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2008;32(3):324-32 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v32n3/v32n3a07.pdf . [ Links ]

2. Peixinho, AL. Educação médica: o desafio de sua transformação [tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2001[acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufba.br/ri/handle/ri/11847 . [ Links ]

3. Pagliosa FL, Da Ros MA. O relatório Flexner: para o bem e para o mal. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2008;32(4):492-9 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v32n4/v32n4a12 [ Links ]

4. Koifman L. O modelo biomédico e a reformulação do currículo médico da Universidade Federal Fluminense. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos. 2001;8(1):49-69 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php? . [ Links ]

5. Engel, GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977; 196(4286):129-36. [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008 - primary health care (now more than ever) [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf . [ Links ]

7. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago press; 1970. [ Links ]

8. Physicians for the twenty-first century. Report of the Project Panel on the General Professional Education of the Physician and College Preparation for Medicine. J Med Educ. 1984 Nov;59(11 Pt 2):1-208. [ Links ]

9. Gomes AP, Costa JRB, Junqueira TS, Arcuri MB, Batista RS. Atenção primária à saúde e formação médica: entre episteme e práxis. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2012;36(4):541-9 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v36n4/14.pdf . [ Links ]

10. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. [ Links ]

11. PereiraJG, Martines WRV, Campinas LLSL, Chueri PS. Integração academia, serviço e comunidade: um relato de experiência do curso de graduação em Medicina na atenção básica no município de São Paulo. O Mundo da Saúde 2009; 33(1): 99-107. [ Links ]

12. Anjos RMP, Gianini RJ, Minari FC, Luca AHS, Rodrigues MP. “ Vivendo o SUS”: uma experiência prática no cenário da atenção básica. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2010; 34:172-183. [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022010000100021 [ Links ]

13. Martines WRV, Machado AL. Instrumentalização do aluno de Medicina para o cuidado de pessoas na Estratégia Saúde da Família: o relacionamento interpessoal profissional. O Mundo da Saúde 2010; 34(1): 120-126. [ Links ]

14. Ruiz DG, Farenzena GJ, Haeffner LSB. Internato regional e formação médica: percepção da primeira turma pós-reforma curricular. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2010; 24: 21-27 [acesso em 27 set 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022010000100004 [ Links ]

15. Costa JRB, Romano VF, Costa RR, Vitorino RR, Alves LA, Gomes AP, Siqueira-Batista R. Formação médica na estratégia de saúde da família: percepções discentes. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2012; 36: 387-400. [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022012000500014 [ Links ]

16. Neumann CR, Miranda CZ de. Ensino de atenção primária à saúde na graduação: fatores que influenciam a satisfação do aluno. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2012; 36:42-49 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022012000300007 [ Links ]

17. Makabe MLF, Maia JA. Reflexão discente sobre a futura prática médica através da integração com a equipe de saúde da família na graduação. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2014;38: 127-132 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022014000100017 [ Links ]

18. Souza MCA, Mendonça MA, Costa EMA, Gonçalves SJC, Teixeira JCD, Almeida Júnior EHR, Côrtes Junior JCS. O Universitário Transformador na comunidade: a experiência da USS. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2014; 38: 269-274 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-55022014000200014 [ Links ]

19. Bezerra DF, Adami F, Reato LFN, Akerman, M. “A dor e a delícia” do internato de atenção primária em saúde: desafios e tensões. ABCS Health Sciences 2015; 40(30): 164-170 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.7322/abcshs.v40i3.790 [ Links ]

20. Gomes LB, Sampaio J, Lins TS. Currículo de medicina na Universidade Federal da Paraíba: reflexões sobre uma experiência modular integrada com ênfase na Atenção Básica. Saúde em Redes 2015; 1(1): 39-46 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.18310/2446-4813.2015v1n1p39-46 [ Links ]

21. Almeida PF, Bastos MO, Condé MA, Macedo NJ, Feteira JM, Botelho FP, Silva RL. Trabalho de campo supervisionado II: uma experiência curricular de inserção na atenção primária à saúde. Interface-Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, 2016; 20: 777-786. [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622015.0692 [ Links ]

22. Silvestre HF, Tesser CD, Ros MA. Avaliação discente de um internato médico em atenção primária à saúde. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2016; 40: 383-392 [acesso em 27 set 2022] Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v40n3e01622015 [ Links ]

23. Cavalcante TM. Uma experiência de integração ensino, serviço e comunidade de alunos do curso de graduação em medicina na atenção básica no município de Maceió. Revista Ciência Plural 2017; 3(3): 69-80 [ Links ]

24. Oliveira ALO, Melo LP, Pinto TR, Azevedo GD, Santos M, Câmara RBG, et al. Vivência integrada na comunidade: inserção longitudinal no Sistema de Saúde como estratégia de formação médica. Interface (Botucatu). 2017; 21(Suppl 1): 1355-1366. [Acesso em 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0533 >. [ Links ]

25. Silva ATC, Medeiros Jr ME, Fontão PN, Saletti Filho HC, Vital Jr PF, Bourget MMM, et al. Medicina de Família do Primeiro ao Sexto Ano da Graduação Médica: Considerações sobre uma Proposta Educacional de Integração Curricular Escola-Serviço. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2017; 41(2): 336-345 [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v41n2RB20160016 >. [ Links ]

26. Teófilo TJS, Santos NLP, Baduy RS. Apostas de mudança na educação médica: trajetórias de uma escola de medicina. Interface (Botucatu) . 2017;21(60):177-188. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0007 >. [ Links ]

27. Poles TPG, Oliveira RA, Anjos RMP, Almeida F. Percepção dos Internos e Recém-Egressos do Curso de Medicina da PUC-SP sobre sua formação para atuar na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2018;42(3):121-128. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v42n3RB20170072 >. [ Links ]

28. Vieira SP, Pierantoni CR, Magnago C, Ney MS, Miranda RG. A graduação em medicina no Brasil ante os desafios da formação para a Atenção Primária à Saúde. Saúde debate. 2018;42(spe1): 189-207. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-11042018S113 >. [ Links ]

29. Coêlho BP, Miranda GMDC, Oscar B. A Formação-Intervenção na Atenção Primária: uma aposta pedagógica na Educação Médica. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2019;43(1 suppl 1): 632-640. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v43suplemento1-20190085 >. [ Links ]

30. Ferreira MJM, Ribeiro KG, Almeida MM, Sousa MS, Ribeiro MTAM, Machado MMT, et al. New National Curricular Guidelines of medical courses: opportunities to resignify education. Interface (Botucatu) . 2019; 23(Supl. 1): e170920. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/Interface.170920 >. [ Links ]

31. Parma FAS, Oliveira RAA, Fernando A. Health Professionals’ Perceptions on the Integration of Medical Students’ Training in Family Health Care Units. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2019, 43 (1 suppl 1): 175-184. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v43suplemento1-20180202 >. [ Links ]

32. Pedroso RT, Nogueira CAG, Damasceno CN, Medeiros KKP, Silva PHC, Veloso WF. A Educação Baseada na Comunidade no Ensino Médico na Uniceplac (2016) e os Desafios para o Futuro. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2019; 43 (4): 117-130. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v43n4RB20180197 >. [ Links ]

33. Peixoto MT, Jesus WLA, Carvalho RC, Assis MMA. Medical education in Primary Healthcare: a multiple-approach experience to teaching, service and community integration practices. Interface (Botucatu) . 2019; 23(Supl. 1): e170794 [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/Interface.170794 >. [ Links ]

34. Rezende VLM, Rocha BS, Naghettini A, Fernandes MR, Pereira ERS. Percepção discente e docente sobre o desenvolvimento curricular na atenção primária após Diretrizes Curriculares de 2014. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2019; 43 (3): 91-99. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v43n2RB20180237 >. [ Links ]

35. Rezende VLM, Rocha BS, Naghettini AV, Pereira ERS. Documentary analysis of the pedagogical project of a Medicine course and teaching in Primary Care. Interface (Botucatu) . 2019; 23(Supl. 1): e170896. [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/Interface.170896 >. [ Links ]

36. Coelho MGM, Machado MFAS, Bessa OAAC, Nuto SAS. Atenção Primária à Saúde na perspectiva da formação do profissional médico. Interface (Botucatu) . 2020; 24: e190740 [Acess 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/Interface.190740 >. [ Links ]

37. Lima ICV, Shibuya BYR, Peixoto MGB, Lima LL, Magalhães PSF. Análise do Internato em Medicina da Família e Comunidade de uma Universidade Pública de Fortaleza-CE na perspectiva do discente. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2020; 44 (01): e006 [Acesso 27 Set 2022]. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v44.1-20190211 >. [ Links ]

38. Brasil. Resolução CES nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do curso de graduação em Medicina. Brasília; 2014 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=15874-rces003-14&Itemid=30192 . [ Links ]

39. Demarzo MMP, Almeida RCC, Marins JJN, Trindade TG, Anderson MIP, Stein AT, et al. Diretrizes para o ensino na atenção primária à saúde na graduação em Medicina. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2012; 36(1):143-8 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v36n1/a20v36n1.pdf . [ Links ]

40. Santos Júnior CJ, Misael JRM, Silva MR, Gomes VM. Educação médica e formação na perspectiva ampliada e multidimensional: considerações acerca de uma experiência de ensino-aprendizagem. Rev Bras Educ Med . 2019;43(1):72-9 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v43n1/1981-5271-rbem-43-1-0072.pdf . [ Links ]

41. Chini H, Osis, MJD, Amaral E. A aprendizagem baseada em casos da atenção primária à saúde nas escolas médicas brasileiras. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2018;42(2):45-53. [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbem/v42n2/0100-5502-rbem-42-02-0045.pdf . [ Links ]

42. Bazak O, Yaphe J, Spiegel W, Wilm S, Carelli F, Metsemakers JFM. Early clinical exposure in medical curricula across Europe: an overview. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15(1):4-10. [ Links ]

43. Boon V, Ridd M, Blythe A. Medical undergraduate primary care teaching across the UK: what is being taught? Educ Prim Care. 2017;28(1):23-8. [ Links ]

44. Oppen JV, Camm C, Sahota G, Taggar J, Knox R. Medical students’ attitudes towards increasing early clinical exposure to primary care. Educ Prim Care . 2018;29(5):312-313. [ Links ]

45. Fazio SB, Demasi M, Farren E, Frankl S, Gottlieb B, Hoy J, et al. Blueprint for an undergraduate primary care curriculum. Acad Med. 2016; 91(12):1628-1637. [ Links ]

46. Carácio FCC, Conterno LO, Oliveira MAC, Oliveira ACH, Marin MJS, Braccialli LAD. A experiência de uma instituição pública na formação do profissional de saúde para atuação em atenção primária. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:2133-42 [acesso em 10 out 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v19n7/1413-8123-csc-19-07-02133.pdf [ Links ]

47. Zurro AM, Villa JJ, Hijar AM, Tuduri XM, Puime AO, Coello PA. Los estudiantes de medicina españoles y la medicina de familia. Datos de las 2 fases de una encuesta estatal. Aten Primaria. 2013;45(1):38-45. [ Links ]

48. Chung C, Maisonneuve H, Pfarrwaller E, Audétat MC, Birchmeier A, Herzig L, et al. Impact of the primary care curriculum and its teaching formats on medical students’ perception of primary care: a cross-sectional study. BMC family practice. 2016;17(1):135. [ Links ]

49. Mariolis A, Mihas C, Alevizos A, Papathanasiou M, Sapsakos TM, Marayiannis K, et al. Evaluation of a clinical attachment in primary health care as a component of undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2008;30(7):e202-e207. [ Links ]

Received: February 15, 2021; Accepted: August 15, 2022

texto en

texto en