Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

Print version ISSN 0100-5502On-line version ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.47 no.1 Rio de Janeiro Jan./Mar. 2023 Epub Mar 20, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v47.1-20220176

REVIEW ARTICLE

Student-related aspects in the construction of the Medical Identity: an integrative review

1Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

2Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Introduction:

The Medical Identity (MI) construction is a dynamic phenomenon influenced by factors related to the student, the educational environment and society.

Objective:

To synthesize the produced knowledge about the student-related aspects regarding the construction of the MI.

Method:

This is an integrative review of empirical studies published in journals indexed in the MEDLINE and LILACS databases, using the term Medical Identity and the descriptors Identity Crisis, Social Identification, Physician’s Role and Professional Role. The inclusion criteria were: full texts available in Portuguese, Spanish, French or English of empirical studies on factors that influence the development of MI focused on student-related aspects and having physicians or undergraduate medical students as participants.

Results:

In the first stage, 1,365 articles were identified. Subsequently, 194 articles were chosen for in-depth reading. Of these, 18 were included for thematic analysis with classification into categories in dialogue with the literature, based on the concept of healthy MI. Most articles were published in the last decade. Three categories were identified: expectation versus reality, related to what the student thinks about what a physician is or should be; the ‘superhero’ physician, related to the caricatured perception of Medicine created by the students themselves and offered by society through TV programs, series and films; and role modeling, which concerns the importance of the student’s practical experience supervised by a preceptor or teacher. The MI built throughout the medical course influences the way medicine is practiced and when it is not consistent with the reality that the recently graduated student encounters, it causes suffering to the physician and interferes with their professional performance.

Conclusion:

Educational institutions, teachers and preceptors must be aware of the expectations and ideals of their students about what it means to be a physician and the role of this professional in society, aiming to promote interventions that help establishing a healthier and more resilient identity construction, particular to the medical profession.

Keywords: Medical education; Medical students; Identity crisis; Physician’s role; Qualitative research

Introdução:

A construção da identidade médica (IM) é fenômeno dinâmico influenciado por fatores relacionados ao estudante, ao ambiente educacional e à sociedade.

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivo sintetizar o conhecimento produzido a respeito dos aspectos referentes ao estudante na construção da IM.

Método:

Trata-se de uma revisão integrativa de estudos empíricos publicados em periódicos indexados na MEDLINE e LILACS, utilizando a expressão medical identity e os descritores identity crisis, social identification, physician’s role e professional role. Os critérios de inclusão foram: textos completos disponíveis em português, espanhol, francês ou inglês de estudos empíricos sobre fatores que influenciam na formação da IM com foco nos aspectos relacionados ao estudante e tendo médicos ou estudantes de graduação em Medicina como participantes.

Resultado:

Na primeira etapa, identificaram-se 1.365 artigos. Foram triados 194 artigos para leitura em profundidade. Destes, incluíram-se 18 para análise temática com classificação em categorias em diálogo com a literatura, tendo como base o conceito de IM saudável. A maioria dos artigos foi publicada na última década. Identificaram-se três categorias: expectativa versus realidade, referente ao que o estudante pensa sobre o que um médico é ou deveria ser; médico “super-herói”, relativa à percepção caricaturada da medicina criada pelos próprios alunos e oferecida pela sociedade por meio de programas, séries e filmes televisivos; e modelagem de papéis, que diz respeito à importância da experiência prática do estudante supervisionada por um preceptor ou docente. A IM construída ao longo do curso médico influencia na forma como a medicina é exercida e, quando ela não é congruente com a realidade que o recém-formado encontra, provoca sofrimento no médico e interfere na atuação profissional dele.

Conclusão:

Instituições de ensino, professores e preceptores devem estar atentos às expectativas e às idealizações de seus alunos sobre o que é ser um médico e o papel desse profissional na sociedade, de maneira a promover intervenções que auxiliem em uma construção identitária mais saudável e mais resiliente às intempéries peculiares à profissão médica.

Palavras-chave: Educação Médica; Estudantes de Medicina; Crise de Identidade; Papel do Médico; Pesquisa Qualitativa

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1950’s, social scientists have observed that medical education needs to be able to provide students with the best available regarding knowledge and skills. Moreover, it should help in the development of a professional identity, so this student can think, act and feel like a physician, that is, be able to build their own identity as a professional1),(2.

Identity construction can be called professional identity construction by some authors, without losing its essential meaning, and is seen as a fundamental step in the transition from being a student to becoming a medical professional. This construction demands a definition of who the person is, their moral values and what they want to accomplish in their life. Therefore, they develop a conception of themselves that consists of goals, beliefs and values to which they are deeply committed and use them as the basis for interaction with the world around them. Medical students are positioned, in the construction of identity, between perceiving themselves as adolescents who left the lay world of patients and effectively becoming physicians3)-(6.

Throughout the course, it is common for these superficial and rudimentary ideals and identity constructions to come into conflict with the lived experiences. Therefore, great emotional tensions are generated, which may harm these students’ emotional and mental health, when old values and beliefs are reexamined in a chaotic manner and are not supervised by more experienced colleagues or teachers3),(4),(7.

An MI can be considered healthy when there has been a gradual transition between the student’s ideals and the reality experienced at the end of the internship and in hospital practices or when there is no confusion, feeling of anguish or anxiety related to the physician’s role in the interprofessional teams and in the society4),(7)-(9. In brief, a healthy MI consists of characteristics such as sensitivity, empathy, integrity, generosity, tolerance, common sense, intelligence, dedication, ability to consolidate and repair7),(10.

The National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN, Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais)11 recommend that the profile of undergraduate students include a general education focused on the demands of the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde). However, the students’ collective imagination remains directed towards specializations and the privatist nature regarding the professional performance in the process of academic education in health5),(6),(12. Considering that among physicians under the age of 25, approximately 67% work exclusively in the SUS13, it is observed that medical students have the perception that working in the public sector offers financial security due to the guarantee of employment and a salary at the end of the month, whereas the private sector offers professional success5),(6),(12.

The topic related to student experiences is one of the aspects of the construct tripod that constitutes MI found in one of the most extensive studies on the subject, the meta-synthesis developed by Rebecca Volpe et al.14. In this 2019 publication by BMC Medical Education, 92 scientific texts were included in the review, of a total of 7,451 titles and abstracts found in the literature search. Three interrelated categories in MI development were revealed: 1) students and their expectations; 2) the educational environment, the role of the preceptor or teacher and the supervised practical experience (role modeling - examples of acting as a doctor that educators provide to students) and 3) society, social systems and curricular structures and their impact on the trained professional14.

In addition to the meta-synthesis by Volpe et al.14, more than thirty MI-related literature reviews were conducted in the last twenty years worldwide. However, none of them included articles published in South America, especially in Brazil, or addressed aspects related to the student as the main topic, or even gathered empirical and exploratory studies.

A well-developed and healthy professional identity is the foundation for a safe and effective clinical practice for all professions in the health area, also regarding the sense of maintaining the physical and emotional well-being of these professionals. University programs, whether related to the curricular part, in the pedagogical core or in the teacher’s figure, play an important role in the development of the students’ professional identity7),(14),(15.

Advances in the understanding of these topics provide new interpretations on the complex process of developing a healthy medical identity in undergraduate medical students. Deficiencies in this identity formation have a negative impact on the clinical decision regarding the therapeutic scheme to be proposed for the treatment of patients, on the physician’s role and on their work in multidisciplinary teams, and even on the physical and mental health of undergraduate students and graduated physicians working in the labor market7),(8),(10.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to synthesize the knowledge produced in empirical studies on student-related issues regarding the construction of the MI, since the previous reviews found in the literature did not address this specific topic.

METHOD

This is an integrative review of articles published in journals indexed in the two main health sciences databases: MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), via PubMed (search system for bibliographic references of the National Library of Medicine - NLM) and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences). These two databases were chosen because they combine bibliographic sources and journals of world-renowned quality, including national and South American articles.

The inclusion criteria comprised: full text available in Portuguese, Spanish, French or English of empirical studies on factors that influence the formation of the MI focused on student-related aspects and having physicians or undergraduate medical students as participants.

The search terms and descriptors used in the research were chosen from the four-item study based on the choice of an adequate descriptor for a research, according to the DeCS (Health Sciences Descriptors): scope notes, indexing notes, hierarchical structure and descriptor concept (DeCS, 2004). After this stage, the analysis of alternative terms of the 22 descriptors related to the MI topic found in the DeCS of BIREME (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information) and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) of the NLM (National Library of Medicine).

To make it possible to analyze the literature in an integrated and comprehensive way, the review was carried out in four stages: identification, selection, eligibility and inclusion. The search for articles on the databases was performed on March 1st and revised in September 2021.

Thematic analysis of the texts was carried out, followed by classification into categories and dialogue with the literature. For this analysis, the steps described in the study by Minayo16 were followed, which comprise reading, understanding and re-reading for familiarization with the objective and subjective contents of the documents found in the review, identifying the analysis topics considering the study objectives, classification of the topics and comparative dialogue with the literature and the creation of an interpretative synthesis. Sixteen articles were included, in addition to those shown in Chart 1, in the introduction and discussion of data.

RESULTS

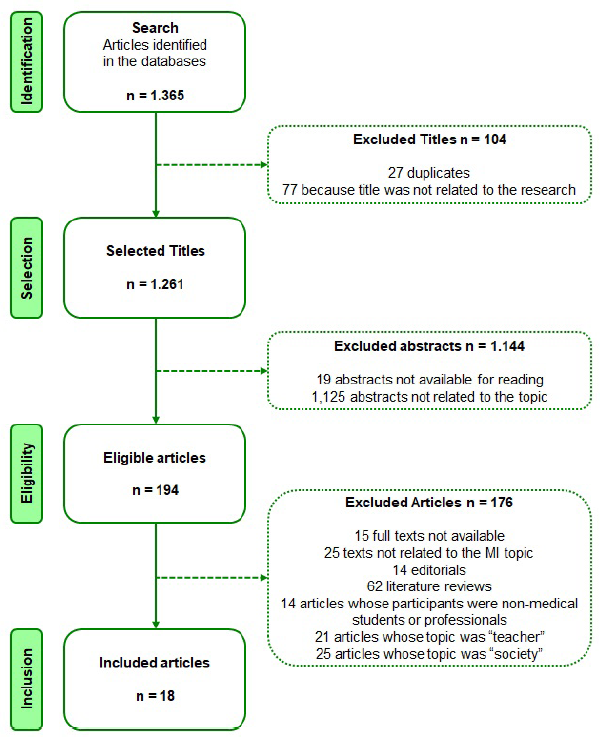

In the first stage, identification, the term Medical Identity and the descriptors Identity crisis, Physician’s role, Social identification, and Professional role were used. The articles were screened by title, abstract and full text. A total of 1,365 documents were identified in the searched databases. When screening by title, 27 were excluded because they were in duplicate and 77 because the title was not related to the current research.

Of the 1,261 remaining titles, 19 articles whose abstract was not available for reading and 1,125 whose abstracts were not related to the proposed topic were excluded.

Thus, 194 articles were screened for full-text and in-depth reading. Of these, 176 titles did not meet the inclusion criteria: 15 because the full text was not available, 25 were not related to the MI theme, 14 were editorials, 62 were review articles, 14 were articles whose research participants were non-medical students or professionals, and 46 studies did not focus on student-related aspects of MI (21 were related to the teacher and 25 to society). Thus, 18 articles were fully analyzed (Figure 1).

Source: Figure prepared by the authors, adapted from the PRISMA 2009 group.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the search and selection process of articles included in the integrative review.

Regarding the date, 97% of the articles were published in the last twenty years, with the majority in the last decade, demonstrating the topic is a current one. Most studies (72% - 13 articles) used a qualitative methodology, while the other five articles used a quantitative methodology.

As for the location where the study was carried out, 56% (ten articles) were developed in South America (five in Brazil), Oceania (two in Australia), Asia (one in Israel and one in Indonesia) and Africa (one in South Africa). The remainder were carried out in North America (four in the US) and Europe (three in the UK and one multicenter survey in the UK and Netherlands).

The articles were organized in Chart 1, which contains the name of the first author, the year of publication, the country where it was carried out, study design, objective, thematic category in which it was included, participants and main conclusions.

Chart 1 Articles included in the integrative review that deal with the 'student' factor in the development of the Medical Identity.

| Authorship Year / Location Design Thematic category | Objectives | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Matos MS 7 2019 / Brazil Qualitative Thematic category I | Identify expectations and reality experienced by medical students. | 77 medical students |

| Machado CBD 17 2018 / Brazil Qualitative Thematic category I | To analyze expectations of becoming a physician during medical school. | 145 medical students |

| Stubbing E 4 2018 / United Kingdom Qualitative Thematic category II | To understand the expectations and prejudices of medical students about what constitutes being a physician. | 23 medical students |

| Winkel AF 18 2018 / USA Qualitative Thematic category II | To understand the development of resilience in residents coping with stressors. | 18 resident physicians |

| Burford B 1 2017 / United Kingdom Quantitative Thematic category I | To establish how medical students identify themselves. | 181 medical students |

| Wainwright E 19 2017 / United Kingdom Qualitative Thematic category II | To investigate how the Professional Support Program (PSP) influences the self-perception of MI. | 08 medical students (internship) |

| Wasityastuti W 20 2016 / Indonesia Quantitative Thematic category I | To determine academic motivation profiles and relationship between PI and MI. | 531 medical students |

| Green MJ 21 2015 / USA Qualitative Thematic category III | To understand, through graphic arts, the experience of medical students. | 58 medical students |

| Lovell B 8 2015 / United Kingdom Qualitative Thematic category III | To analyze how student communities influence PI and MI development. | 32 medical students |

| Talisman N 22 2015 / USA Quantitative Thematic category I | To explore whether mindfulness training helps in the construction of MI. | 62 medical students |

| Barr J 23 2014 / Australia Qualitative Thematic category I | To analyze the contact of students with chronic patients and the influence on patient-centered IM. | 67 medical students |

| Kligler B 24 2013 / USA Qualitative Thematic category II | To understand the impact of the beginning of the third year on the students’ well-being. | 173 medical students |

| Iyer A 25 2011 / Australia Quantitative Thematic category I | To assess the effects of nostalgia and continuity of identity on psychological well-being. | 120 undergraduate students |

| Sabino C 26 2010 / Brazil Qualitative Thematic category III | To understand the role of the outpatient clinic in the construction of MI in the beginning of the medical career. | 12 physicians |

| Machado MA 27 2009 / Brazil Qualitative Thematic category I | To investigate the construction of the MI of palliative care physicians. | 06 physicians |

| Draper C 28 2007 / South Africa Qualitative Thematic category III | To explore the perceptions of medical students about medicine and professional practice. | 193 medical students |

| Fiore MLM 21 2005 / Brazil Qualitative Thematic category III | To explore psychological and social factors involved in the choice of medical specialties. | 40 physicians |

| Rosenberg EH 30 1979 / Israel Quantitative Thematic category II | To investigate how first-year students of the medical course perceive themselves in contact with patients. | 62 medical students |

Caption: PI - professional identity; MI - medical identity.

Source: chart prepared by the authors.

In the analysis of the articles, three main thematic cores were identified, which originated the classification categories: I) expectation versus reality: the students’ expectations about what a physician is or should be (eight articles); II) ‘superhero’ physician: the caricatured perception of Medicine created by the students themselves and offered by society through TV programs, series and films (five articles); III) role modeling: the importance of the student’s practical experience supervised by a preceptor or teacher (five articles).

Category I: Expectation versus reality

In this category, eight articles were included, which addressed the students’ thoughts about what constitutes being a physician, especially from the moment they are approved in the university selection process and experience the transition from ‘lay public’ to ‘student of Medicine and future physician’.

Students, even in the early days of the medical course, already have a pre-formed conception of the type of professional they aspire to be through the idealization and expectation of what constitutes ‘being a physician’. This pre-formed conception is similar to the understanding that the lay public has about Medicine and is full of previous concepts that may or may not become the reality7),(17. In addition, the motivation for choosing the profession influences the expectations these students develop before and during the course. In the study by Mariana Santiago de Matos et al.7, it was evident that “(...) the choice of the profession - a childhood ‘dream’ - is largely due to idealized conceptions about the physician, a figure that ‘does good’, ‘saves lives’, ‘prevents death’, ‘brings happiness to others’ and ‘has social status’” (p.159)7.

However, the motivations and expectations of this ‘child’s dream’ change drastically throughout the medical course. There is a decrease in the humanist, critical, reflective and ethical ideal in an inversely proportional way to the increase in the ideal of achieving financial return to the detriment of humanist and ethical relationships, in an ultra-specialized clinical practice, which follows the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) for Medicine from 2001 and 201411),(17),(27.

The change in these expectations regarding physicians can be explained by the contrast between the expected role of a medical student and the experience during the insertion of this student in real-life medical practice. During the course, students are expected to develop a set of technical skills and competences, but also psychological characteristics such as empathy and a sense of social responsibility. The competitive academic environment and the excessive appreciation of overspecialization have a negative impact on these students’ perspectives regarding the profession. One perceives the transformation of the generalist and humanist profile present at the beginning of the course into a profile, at the end of the course, focused on the job market, financial return and the high social status that one aims to achieve7),(9),(17),(27.

Even though they only become doctors after the minimum six years of undergraduate school, it is common for students, at the beginning of the course, to already identify themselves more strongly as ‘physicians’, than still as ‘medical students’. This precocious self-perception creates tensions and frustrations in identity formation. Students in the first semesters perceive themselves more as ‘physicians’ than the students attending the final semesters of the course (internship). In turn, internship students - who are soon to be physicians - suffer identity crises when they do not consider themselves capable of becoming physicians, with apprehensions and fears regarding their entering the job market and professional life, experiencing the ‘imposter syndrome’9.

Studies show that the motivations for choosing a profession also change. One example of this situation is the encouragement of altruism to help others being replaced by individualism and the search for prominent and satisfactory social and financial status9),(20),(22),(23),(25),(27.

Articles have described that a distorted identity self-perception, with unrealistic and psychologically unsolved expectations during the medical course, generate negative consequences for the psychological well-being when students find they will not be able to achieve the socially expected stereotypes7),(9),(20),(25. On the other hand, Australian researcher Aarti Iyer25 points out that “identity transitions that are planned, structured and supervised by preceptors usually have positive consequences for the individuals” (p.106)25.

Category II: “Superhero” physician

This category included the five articles that addressed the caricatured perception of Medicine created by the students themselves and offered by society through TV programs, series and films. It is common, among students, to have a view of the physician where the white coat becomes the superhero’s cape, an invincible being who is not susceptible to any physical or emotional storms.

There is, therefore, a stereotyped deification that can be socially perceived in the preconception of the hero-physician caricatured in the figure of the ‘doctor’. This hero-physician is a person who should never show weakness or need health care, has great social and financial status, is capable of being a natural leader in health teams and manages to solve all the problems that arise in front of them. This perception is still maintained in the first months of the undergraduate course and decreases only in the last semesters of the course, when students are exposed to the reality of the profession, in internship19),(24.

This deification is different from the expectations created by students before entering university, because imagining situations that may become real (or not) is something inherent to every human being. However, in Medicine, these expectations of imaginary situations can transcend everyday situations and ‘patient care’ can be perceived as a true ‘act of heroism’, compared to the great deeds performed by superheroes in fiction19),(24),(30.

The observation of this characteristic in the behavior of medical students is not new. According to Rosenberg EH et al.30, in a study carried out at Tel-Aviv University in Israel, when “students were asked to check their position - closer to the physician’s or patient’s position - almost 80% chose the physician’s position and classified this professional as ‘extraordinary’ and ‘wise’, including those recently enrolled in the medical course” (p.334)30.

More recent studies confirm this particularity and reveal that students, even if they have just started the first semester, feel like ‘superhero physicians’ and behave as such in society. They imagine performing an extraordinary cardiopulmonary resuscitation amidst a crowd or saying ‘it’s a beautiful day to save lives’ in reference to a character from a TV series. It is also common for family members and friends to see the student, still a beginner in the profession, as a reference in terms of health issues, even if the student was approved in the selection process just a few days before4),(19.

Students describe, in research, the difficulty of making healthy choices in the face of the challenges of medical school, as they feel pressured to be ‘perfect’ in order to become a ‘model’ for their own patients. Benjamin Kligler et al.24 highlight that some students characterized this modeling towards patients as “challenges that encouraged them to be more active and effective in managing their own health; others characterized it as insurmountable obstacles that prevented them from making healthy choices” (p.535)24.

Winkel et al.18 point out that, even though it is a matter of concern, this is “a natural phenomenon of the development of MI and is based on the socially understood vocation of physicians for care”. By finding peer support and connecting with the meaning of work, the initial ‘call’ to the ‘heroism’ of patient care work can be strengthened, rather than weakened, by the difficult experience of realizing that illness and death are natural processes of life, and not great villains to be fought. For this experience to strengthen the students’ budding MI, during in-service training, the coping mechanisms and reflection on the uncertainties and adversities presented by the experience of being a real physician should be expanded18,30. Upon discovering themselves to be fallible, human and susceptible to stress and conflicts, there is a rupture in the students’ perception of the hero-physician. This rupture develops a healthier MI that is crucial to the real-life physician, improving connections within the medical community, the feeling of personal self-fulfillment at work and the development of physical and emotional self-care practices18.

Category III: Role Modeling

Five articles were included in this category, which addressed the importance of practical experience supervised by a preceptor or teacher in the identity development of the student under their tutelage and the action strategies of preceptors/teachers and educational institutions.

According to Fiore and Yazigi29, although students have different ways of dealing with the anxieties generated by medical practice, the emotional resources used for managing and dealing with situations that generate tension and anxiety “depend on each one’s personal history and own symbolic capital. The hierarchy of values in Medicine and its different specialties can be considered a collective defense mechanism (of students) against anxieties arising (...) from constantly dealing with situations of impotence” (p.206)29. This safeguard acts against the anxieties resulting from the exercise of the profession in the daily life of the public and private labor market and the constant dealing with situations of impotence when facing what needs to be done and what can effectively be done for the patient’s benefit29.

These frustrations and unmet expectations in relation to the course and medical practice end up compromising the willingness to learn and the adequate construction of the MI. For this reason, educators are expected to be aware of the students’ previous expectations and concepts in relation to Medicine, aiming to detect early conflicts between these perceptions and reality. Therefore, they will be able to help in the development of resilience and psychological mechanisms that will strengthen students to face these emotional and physical stressors8),(28),(29.

Medical preceptors or professors have experienced the construction of their own MI and are the best suited for early detection of students’ identity conflicts, aiming to mitigate these emotional disorders. Therefore, it is essential to offer psychopedagogical support during the medical course while MI is being developed in undergraduate students, since there is great resistance on the part of graduated professionals to seek specialized psychological help. Recent research has shown that the need to seek help from a psychological support service seems to ‘break’ the self-perceived MI, especially when it was built on the basis of unrealistic stereotypes created and consolidated throughout the course. Even if this ‘break’ and these psychological supports are useful in establishing new parameters, new motivations and identity restructuring in a healthier way, there is still great resistance on the part of physicians in carrying out a process of self-analysis, guided by trained professionals. Thus, teachers play a crucial role when it comes to detecting emotional conflicts in their students, mediating solutions and suggesting seeking specialized psychological support 8),(21),(26.

According to Sabino and Luz26, the teacher works, even strategically, as a mediator in the dynamics of power relations, rectification of expectations and identity construction of undergraduate and graduate students. This happens when these students aim to care for highly complex patients, despite the fact that 80% of Brazilian medical care is of low complexity and performed in outpatient clinics. The authors point out that “students tend to use the terms “messed-up clinic” (a place where there are only “messed up” people), “trash clinic” (a reference to “trashy”, or poorly dressed people) and “stalling clinic” (a place where time is wasted by ‘stalling’ other people) as synonyms of “outpatient clinic” (p.1360)26.

In addition, the experiences of students in the pre-clinical cycle result in an identity related to traditional models centered on the physician, regardless of the country where they study Medicine. Early interaction with the patient helps build a healthier MI by making the students face a concrete reality of what they will find at the end of the course. This experience changes the student’s focus towards a more patient-centered MI. This focus can be built from the undergraduate student’s involvement in everyday practical tasks, such as welcoming patients in a waiting room, becoming responsible for some stages of care or carrying out activities in close contact with patients, supporting the feeling of ‘being a real-life doctor’. This involvement constitutes a legitimate participation in supervised patient care, even if peripheral in the beginning of the course, and is capable of shaping the students’ professional identity. In this context, the figure of the preceptor or professor emerges as indispensable in modeling roles in medical practice, positively or negatively influencing the emergence and development of MI in their students21),(28),(29.

DISCUSSION

The debate about the factors that influence the development of MI in undergraduate students is not recent. As Julio de Mello Filho10 warns us, “the physician-centered study becomes arduous” because many authors dedicate themselves to the study of Medicine as a science; however, “those who practice it remain between the lines”. According to Adolfo Hoirisch31, the territory of the study on MI development is stony and rough because “the physician, committed as they are to studying the patient’s identity, forgets to analyze their own identity. Certain physicians shield themselves in the professional role as if, by doing so, they would invalidate their condition as human beings”(p.5)31. If physicians and teachers themselves suffer from crises in their identity processes, students who look up to these professionals to build their nascent MI go through and experience the same conflicts10.

There are two identities that constitute the medical professional and that can be analyzed as the two strands of a double helix DNA: the identity as an individual and the identity as a professional. Both form parallel threads that intertwine and each thread must have the potential of resilience to accommodate the other. However, this burden of bending and shifting to accommodate one identity seems to fall more on the individual side, with the professional side remaining more fixed and unchanging. Consequently, the individual’s expectations can be suppressed by the professional reality, creating feelings of anxiety, frustration and inadequacy, which may result in psychological and psychiatric disorders that lead to depression and abandonment of the profession2),(7),(14),(17.

The MI development naturally involves a process of experimentation, changes and uncertainties that, ideally, results in the successful reconciliation of ideals, values and conflicting roles2),(14. However, what was demonstrated by the articles included in this review is that the vast majority of students are not able to deal emotionally with these identity conflicts. The consequences of these unmet expectations generate frustrations, psychological disorders and the development of an unhealthy MI. This “ill” MI motivates a low quality in the practice of Medicine by this student7),(17. As a result, specialties considered to be the ‘roots’ of Medicine, such as pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, gynecology-obstetrics and public health are being depleted, as opposed to what was required by the DCN of 2001 and 20145),(6),(11),(12.

Another reason for the difficulty encountered by students undergoing the process of developing a healthy identity is the fact that Generation Y (Millennials) are entering Higher Education institutions, establishing a contemporary context that demands a strategic restructuring of educational didactics in medical schools. This generation is constituted by individuals who have a striking characteristic in common: they were born in the late 1990s and enjoy a visceral relationship with technology and the digital environment, with the highly competitive job market, with short-lasting emotional ties and with the dissolution of labor rights7),(9),(14),(32),(33.

The authors point out that medical educators (teachers and preceptors) should pay close attention to the messages expressed by students through intra- and extra-class dialogues aiming to deeply reflect on what these messages can mean for medical education and for the local culture. Moreover, educators should consider new teaching methods and new techniques for teacher-student interpersonal interactions in the curricula of medical schools 1),(21),(28),(29),(34. Therefore, teachers and preceptors will be able to encourage and guide the student towards a humanist, critical, reflective and ethical professional, the profile recommended by the DCN of 2001 and 20147),(11),(17.

Several studies emphasize the importance of medical curricula focused on the personal and professional development of medical candidates. However, in addition to developing good curricula, it is essential that medical education institutions encourage and validate the function of professors in role modeling and identity building for your students. This validation must be carried out, especially, with the purpose of verifying how the students deal with the expectations regarding the profession, with the changeable perceptions about what it is to be a doctor, with the natural transition that the apprentice experiences when he stops being a “ hero-doctor” and become a “real-doctor” and, above all, with the influence of his teachers in the formation of his MI1),(2),(14.

As can be seen, the construction of the professional identity in Medicine is a dynamic phenomenon that even contributes to good conducts in clinical practice. This significantly impacts the physicians’ self-confidence in sustaining a line of reasoning in the diagnosis and treatment of patients under their care when, for instance, divergences in clinical conduct occur between the physician and the other professionals of a multidisciplinary team1),(15),(34.

The interaction between ‘the student, the teacher and the patient’ helps in role modeling as it teaches the neophyte to act, think and behave like a physician based on the relationships they experience. Regardless of the country where the study was carried out, including Brazil, these two student-related topics were significant.

It is worth remembering that for a broad discussion on the MI theme, it is necessary to include the other factors that interfere with its construction. Therefore, this review study has this limitation, of being restricted to factors intrinsic to the student. Extrinsic factors that influence identity formation, such as the medical curriculum and society’s expectations regarding the profile of physicians to be trained at universities, were not addressed. However, the recent characteristic of most studies on the subject highlights its importance. No other student-related categories were observed in previous national or international reviews.

Another limitation is the scarce national indexed literature. Most of the Brazilian materials are found in theses, dissertations and non-indexed books, not available in digital media and published as limited editions. In the articles from South America, in addition to the evidenced lack of studies, peculiarities were found, such as the focus on influences that are intrinsic to the student, such as the contrast between expectations and the reality of the profession, the discrepancies between the idealized ‘hero-physician’ and the ‘real-life’ one, the path taken by the student in choosing Medicine as a profession and the motivation of newly graduated physicians to define the specialty to be followed. Few national analyses were found regarding the modeling of roles that teachers and preceptors provide to medical students and other factors that are extrinsic to students, such as the curricular structure and teaching methodologies in MI development.

CONCLUSION

This integrative review shows that the MI development is a complex phenomenon that involves multiple factors of an individual, educational and social nature, regarding those directly related to the student. The reviewed studies clarify the importance of educational institutions being aware of the natural transition that occurs during the undergraduate course, related to the expectations and idealizations of their students about what constitutes being a physician and the role of this professional in society. Moreover, they emphasize the students’ perception of the physician as a ‘superhero’, which causes serious identity conflicts. Another topic that stands out in the articles included in this review is the importance of the experience that students acquire in clinical practice supervised by a preceptor or teacher.

The main recommendation of this review is the need for everyone who works directly or indirectly with undergraduate students, including teachers, preceptors and teaching institutions, to be able to identify adversities in the MI development of their students, aiming to promote interventions that can help build a healthier identity, which is more resilient to the conditions that are particular to the medical profession.

REFERENCES

1. Adema M, Dolmans DHJM, Raat JAN, Scheele F, Jaarsma ADC, Helmich E. Social interactions of clerks: the role of engagement, imagination, and alignment as sources for professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1567-73. [ Links ]

2. Barone MA, Vercio C, Jirasevijinda T. Supporting the development of professional identity in the millennial learner. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20183988. [ Links ]

3. Schoen-Ferreira TH, Aznar-Farias M, Silvares EFDM. A construção da identidade em adolescentes: um estudo exploratório. Estud Psicol (Natal). 2003;8:107-15. [ Links ]

4. Stubbing E, Helmich E, Cleland J. Authoring the identity of learner before doctor in the figured world of medical school. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(1):40-6. [ Links ]

5. Ferreira MJM, Ribeiro KG, Almeida MM, Sousa MS, Ribeiro MTAM, Machado MMT. Novas Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para os cursos de Medicina: oportunidades para ressignificar a formação. Interface comum Saúde Educ. 2019;23(supl 1):e170920. [ Links ]

6. Cândido PTDS, Batista NA. O internato médico após as diretrizes curriculares nacionais de 2014: um estudo em escolas médicas do estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2019;43:36-45. [ Links ]

7. Matos MS de, Ferraço CM, Rosa JCA, Bastos JA, Brandão PC. Primeiro período de medicina: choque de realidade e o início da construção da identidade médica. Rev Psicol Saúde. 2019;11(3):157-71. [ Links ]

8. Lovell B. “We are a tight community”: social groups and social identity in medical undergraduates. Med Educ. 2015;49(10):1016-27. [ Links ]

9. Burford B, Rosenthal-Stott HES. First and second year medical students identify and self-stereotype more as doctors than as students: a questionnaire study. BMC Med Educ . 2017;17(1):1-9. [ Links ]

10. Mello Filho J de. Identidade médica: o normal e o patológico. In: Mello Filho J de, editor. Identidade médica. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 2006. [ Links ]

11. Brasil. Resolução nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União; 2014. [ Links ]

12. Fernandes DAS, Taquette SR. Being a doctor in Brazil in the conception of medical students. Res Soc Dev. 2020;9(11):e74691110595. [ Links ]

13. Scheffer M, Cassenote A, Guerra A, Guilloux AGA, Brandão APD, Miotto BA, et al. Demografia médica no Brasil 2020. São Paulo: FMUSP, CFM; 2020. [ Links ]

14. Volpe RL, Hopkins M, Haidet P, Wolpaw DR, Adams NE. Is research on professional identity formation biased? Early insights from a scoping review and metasynthesis. Med. Educ. 2019;53(2):119-32. [ Links ]

15. Matthews J, Bialocerkowski A, Molineux M. Professional identity measures for student health professionals - a systematic review of psychometric properties. BMC Med Educ, 2019;19(1):1-10. [ Links ]

16. Minayo MCS. Análise qualitativa: teoria, etapas e confiabilidade. Cien Saude Colet. 2012;17(3):621-6. [ Links ]

17. Machado CDB, Wuo AS. Processo de socialização na formação identitária do estudante de medicina. Trab Educ Saúde. 2019;17(2):e0020840. [ Links ]

18. Winkel AF, Honart AW, Robinson A, Jones AA, Squires A. Thriving in scrubs: a qualitative study of resident resilience. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):1-8. [ Links ]

19. Wainwright E, Fox F, Breffni T, Taylor G, O’Connor M. Coming back from the edge: a qualitative study of a professional support unit for junior doctors. BMC Med Educ . 2017;17(1):1-11. [ Links ]

20. Wasityastuti W, Susani YP, Prabandari YS, Rahayu GR. Correlation between academic motivation and professional identity in medical students in the Faculty of Medicine of the Universitas Gadjah Mada Indonesia. Educ Med. 2018;19(1):23-9. [ Links ]

21. Green MJ. Comics and medicine: peering into the process of professional identity formation. Acad Med . 2015;90(6):774-9. [ Links ]

22. Talisman N, Harazduk N, Rush C, Graves K, Haramati A. The impact of mind-body medicine facilitation on affirming and enhancing professional identity in health care professions faculty. Acad Med . 2015;90(6):780-4. [ Links ]

23. Barr J, Bull R, Rooney K. Developing a patient focussed professional identity: an exploratory investigation of medical students’ encounters with patient partnership in learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(2):325-38. [ Links ]

24. Kligler B, Brian L, Nadine TK. Becoming a doctor: a qualitative evaluation of challenges and opportunities in medical student wellness during the third year. Acad Med . 2013;88(4):535-40. [ Links ]

25. Iyer A, Jetten J. What’s left behind: identity continuity moderates the effect of nostalgia on well-being and life choices. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(1):94-108. [ Links ]

26. Sabino C, Luz MT. O ambulatório no discurso dos médicos residentes: reprodução e dinâmica do campo médico. Physis. 2010;20(4):1357-75. [ Links ]

27. Machado MA. Cuidados paliativos e a construção da identidade médica paliativista no Brasil [dissertação]. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2009. [ Links ]

28. Draper C, Louw G. What is medicine and what is a doctor? Medical students’ perceptions and expectations of their academic and professional career. Med Teach. 2007;29(5):e100-7. [ Links ]

29. Fiore MLM, Yazigi L. Especialidades médicas: estudo psicossocial. Psicol Reflex Crít. 2005;18(2):200-6. [ Links ]

30. Rosenberg EH, Medini G, Lomranz J. Aspects of differential role perception of Israeli medical school students. Med Educ . 1979;13(5):329-35. [ Links ]

31. Hoirisch A. O problema da identidade médica [tese: concurso para professor titular de Psicologia Médica]. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 1976. [ Links ]

32. Coyer M. Medicine and Improvement in the Scots Magazine; and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany (1804-17). In: Benchimol A, McKeever GL. Cultures of Improvement in Scottish Romanticism, 1707-1840. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2018. p. 192-212. [ Links ]

33. Best S, Williams S. Professional identity in interprofessional teams: findings from a scoping review. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(2):170-81. [ Links ]

34. Logghe HJ, Rouse T, Beekley A, Aggarwal R. The evolving surgeon image. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(5):492-500. [ Links ]

Received: June 21, 2022; Accepted: January 31, 2023

text in

text in