Introduction1

There are innumerable lines of methodological approaches and assumptions that allow us to understand the proximities and distances between the West and the East or, more specifically, between the West and China, which have been thematized over the last hundred years. This methodological diversity, even if it is not for my part disregarded, will not be directly problematized here. I am not unaware of the clash between the relevance of using terms and methods such as "comparative philosophy," "intercultural philosophy," "transcultural philosophy," and others. Nor do I disregard the elementary problems arising from the use of general terms such as "West," "East," "China," and others, which at first glance seem vague and empty. I am also clear about the level of complexity that is at stake and the high risk that I incur in proposing to do what I propose to do here: to discuss a subject-matter as broad and general as the subject-matter of this analysis. Knowing these risks, I develop my reflection, not to prove the collapse of the proposed undertaking, but to awaken a debate on a single issue, which, in my view, is the core of the great objection that prevents China2 from assimilating central elements of the West, such as individual liberty, democracy, human rights and private property, as conceived by Western modernity.

The purpose of this analysis is to point out some elements of the Western tradition, in contrast to elements of the Eastern tradition, which enable us to better understand the possible consequences of the unconditional assimilation by China of these fundamental aspects of the Western tradition. In this way, I anticipate the main purpose of this text, which is, in my view, to explain why it is not possible for China to simply assume Western "values" as a natural consequence of openness to the market economy, without having to give up what makes it what it is. The task, therefore, is to think about the relationship between modernity and tradition in China today, from a certain conception of "modernity", without disregarding, but also, without problematizing, the intense debate that has already occurred around the question itself. The purpose of this analysis is not, therefore, to revisit the monumental discussion about all the consequences of modernization for China, but rather to point out one aspect which, in my opinion, has not yet been properly considered: the difference in the formation of the individual in the West and in China and the consequences of these distinctions specific for the formation of modernity in China. The post-discussion then takes place around modernity with Chinese characteristics.

What we call modernity is an extremely complex project, presenting a very wide range of aspects, forged, progressively, from the theoretical bases elaborated in the West, from the Ancient Greeks to the present day. It is definitively structured after the Middle Ages, is permanently redefined, and in the twentieth century it goes through several phases, having even had its end declared several times and being replaced by postmodernity. The project of modernity is made up of subprojects that allow us to speak of specific modernities such as the modernity of the industrial park, scientific and technological modernity, economic, architectural, philosophical, agricultural, political, etc. This diversity of subprojects of modernity forms a great "package" that can only be well understood from some central elements, which connect with the Western conception of the individual, elaborated in the West from its beginning, with Aristotle. The analysis of the formation of the modern individual is, in my view, the central element of the debate on the universal3 character of the modernity project, presented as the great solution for all the "evils" of all the peoples of the earth.

It is only possible to discuss the question of modernity as a universal project if we consider its historical-philosophical construction, since such a project necessarily presupposes the substitution of all types and concepts of individuals, present outside the Western world, by a single model of the individual, by an individual who aspires to reach the ultimate ideal of the project of modernity: individual freedom as an elementary and universal value, which, in turn, underlies other values such as the inalienable right to private property and a legal and contractual system that regulates their possession, representative democracy and human rights. In this way, the conception of the individual that founds the project of universal modernity is what I designate from now on as the atomic individual,4 an individual who subsists in and of themselves, delineated from Western philosophical references, from Aristotle to Hegel, passing through Descartes, Voltaire, Locke, and Mill. This modern Western individual has very distinct characteristics from the concept of the interrelational, networked individual that takes shape in the Eastern world, principally in China, from its own philosophical bases such as Zhuangzi and Laozi Taoism, from the moral and political philosophy of the Confucian Tradition and Mahāyāna Buddhism that was systematized by the Indian Buddhist monk Nagarjuna and decisively influences Chinese thought from the second century AD. In this way, I think that the project of modernity and its claim to universality developed in the West and the intense conflict to accept it, to refuse it or to accept it in part, which marks China from the May Fourth Movement, 1919 to the present day, can only be well understood, in their basic dimensions, from their genesis and their unfolding, that is, from their historical-philosophical bases.

The historical-philosophical understanding of these two aspects, on the one hand, the project of construction of modernity and consequently its foundation, which is the Western atomic individual and, on the other hand, a project under construction, which is based on the conception of the relational individual or networked individual in the Eastern world, specifically in China today, is the basis for understanding the current intense debate on the question of modernity in China, its relation to the claim to universality of the project of Western modernity and to its own tradition. The central question is, therefore, about the possible consequences for China, of unconditionally assuming the whole project of Western modernity. Specifically, if it assumes parts of the modernities - technical, scientific, aesthetic modernity and the modernity of the market economy - it must also assume its foundation, which is the project of an atomic individual replacing the project of the relational networked individual. From this, necessarily, there are several others, the first of which is the possibility of China assuming the particular projects of Western modernity and at the same time maintaining the fundamental element of the Chinese tradition, which is its particular conception of the non-isolated individual. In the final analysis, if it is possible to reconcile modernity and tradition in China today.

Philosophy thus becomes not a theoretical discipline "outside of reality", exercised by "lunatics" in complete leisure (full idleness), but rather the most concrete and principle way of access to the understanding of the historical formation of the conceptions of individuals, which are forged in the West and in the East. In this sense, the return to the different forms of logic elaborated from Ancient Greece, India and China, to predicate logic and relational logic and their respective unfolding, are basic presuppositions for the understanding of the clash around the overpowering domain of the technique, Western science, and the market economy, which also impose a unique conception of the individual, specifically forged within the Western philosophical tradition, which excludes the philosophical tradition of Eastern thinkers, especially Confucius, Laotzi, Zhuangzi, and Nagarjuna.

The central objective of the first part of this reflection is to present the main logical-ontological foundations that allow us to better understand the bases of Eastern thought and, indirectly, to support the analysis developed in the last part of this text on the formation of what we call "individual" or "individuality" in the West and China. As a methodological counterpoint, I resort to the comparison of these bases with some elements of Aristotle's Metaphysics, mainly to the demonstration of the axiomatic character of the principle of non-contradiction and its linguistic, logical-ontological presuppositions, which are the bases of what I generally designate as predicate logic. The basic purpose of this resource is to clarify the most important points of what I call the relational logic present in the main texts of Māhāyana Buddhism and Taoism, which are the basis of the two main currents that form Zen Buddhism, which in turn is one of the main philosophical references of the Kyoto School. Here I use slightly unorthodox terms, the terms predicate logic and relational logic as synonyms of the bases underlying both Western and Eastern traditions, without entering into the internal debates of the various schools and of the various definitions of logic present both in Western and Eastern traditions. For what I propose, I will take as reference some passages of the text of Nagarjuna entitled Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way (Nagarjuna, 2016), Chapter 11 of Dao De Jing (Laozi, 2002) and Book IV of Aristotle's Metaphysics (Aristotle, 2014).

I make use of the resource of opposition between relational logic and predicate logic in light of the presupposition of the substantial logical-ontological character of the fundamentals of Aristotle's metaphysics and the non-substantial logical-ontological character of the metaphysics of Nāgārjuna and of Laozi. In this way, I inexorably bind the foundation of predicate logic to the substantial character of the world, as presupposed by Aristotelian logic, and the foundation of relational logic to the non-substantial character of the world, as presupposed by the Daoist and Nagarjunian logics.

In order to discuss the distinction between predicate logic and relational logic, it is also necessary to address some issues that are presupposed or circulating around this problem. The first is the assertion that all relational statements would necessarily be reducible to predicate statements. This point is important for the analysis that will be developed next, because it is a possible overwhelming objection to the possibility of a non-predicative logic, since the relational character of a proposition would be due to the junction of predicate statements and that, in the last instance all relational statements would be reducible to predicate statements. That the relational character of any statement can only be considered as a junction of predicate statements and that the validity of a relational statement can only be verified from its dismemberment in predicate statements. That is, in order to verify the validity or character of truth of a relational statement it must necessarily be decomposed into predicate statements, and this would be the demonstration that no judgment of knowledge could be based on relational statements. In this sense, the relational assertion "the glass is full of water" could only have its truth value verified from its decomposition into elementary predicate statements such as, for example, "the cup is impermeable" and "water is liquid." We have, therefore, a relational assertion made up of two predicative assertions in which "glass" and "water" assume the functions of subjects, with specific predications and, necessarily, mediated by the copula “to be.”

The question of the reducibility of statements related to predicate statements leads directly to another central point in order to discuss the differences and proximities between Western and Eastern thought: that of the presupposition of a predicative structure of language and of the necessity of the existence of the verb to be as a copula, for the formation of predicate statements, and, consequently, for the possibility of verifying their character of truth. This point brings us to the heart of one of the major controversies in the history of Western philosophy, namely, that of the presumably eminently Greek character of philosophy because of the properties of the Greek language, which would have made it possible to verify the truth of an argument from its logical-linguistic composition. The property of the Greek language for philosophy would be precisely in the fact that it is more adequate for the formulation of the predicate statements in their basic form S is P.

The third point, central to my analysis here, is the presumed ignorance of the concept of substance5 outside Greek philosophy. As the debate around this concept is one of the pillars for the designation of the original concept of philosophy in Greece and remains in some way in its later development in all Western philosophy, its nonexistence in other traditions, such as Chinese and Indian, would be one of the basic indications of the Greek character of philosophy. To discuss, therefore, the existence or not of the idea of substance at the origin of Chinese and Indian thought, as opposed to its indisputable existence and its determining role in ancient Greek thought, would be one of the elements that would allow us to define the status of philosophy and to ask for its existence outside the Greek-Western world.

In this sense, the question of the presumable necessary reducibility of relational statements to predicate statements, of the existence of the verb to be as a copula in the ancient Greek, as the basis for predicate logic and the clash over the ultimate substance of all things are intrinsically linked and form the theoretical framework that allowed the Western philosophical tradition to delimit the boundaries of what it itself termed philosophy.

As a starting point for the analysis of the fundamental assumptions of the constitution of the concept of the individual in the West and China, I will resort to the assertion that the basis for a clear understanding of the problem is present in three ancient thinkers: Aristotle, Nāgārjuna and Laozi. The choice of these respective philosophers is directly linked to the methodological intention I have in view, namely, the clear exposition of the problem of the first substance, which founds both Western and Eastern philosophy: for the West affirmatively and for the East negatively. The problem of the first substance is not addressed exclusively by these three ancient philosophers. Moreover, we have distinct developments of this issue in both traditions. However, it is in these three thinkers that this problem will stand out in a particularly central and exhaustively discussed way. As a consequence of the unfolding of the problem of substance, there inevitably emerges another previous question that cannot but be thought of: what are the logical references, directly linked to the different argumentative structures, that underlie these three forms of understanding of what I refer to as “the problem of substance.” This question already anticipates the provocative tone of this approach by directly opposing current conceptions within Western philosophy that affirm the nonexistence of the concept of substance in the Eastern world.

Predication, Principle of Non-contradiction and Substance in Aristotle

The problem of movement does not become central to Greek philosophy by a mere magical awakening of reason, in the face of myth, but rather from an extreme indicative that points to the action of movement in its most threatening form: the putrefaction of bodies. With the perception of the putrefaction of the body of the other, we have the first moment of the understanding of death as a psychic phenomenon. However, it is through the transposition of the perception of the putrefaction of the body of the other to the possible putrefaction of my own body that the problem of mutation, of the flow of everything, becomes the problem that founds philosophy. Faced with the radical state of the movement of all things, with the putrefaction of the body itself, the "I" encounters the passibility of the axiomatic character of impermanence and is reluctant to admit its own dissolution, for something must remain, something must be outside of the overwhelming character of the movement. It is precisely in this context that I situate the clash between Aristotle and Heraclitus in Book IV of Metaphysics and classify this moment as one of the most emblematic and influential passages in the history of Western philosophy.

One of the most influential works in the history of Western philosophy, Aristotle's Metaphysics, is, in fact, a posthumous compilation of several texts left by him that were edited a few centuries after his death. One of the main features of this book is the character of synthesis that it presents in several distinct passages, as can be explicitly perceived in his book, in which the author presents to us, in its most elaborate form, the most important of the three basic principles of its logic: the principle of non-contradiction. The argumentative structure presented in Book IV of Metaphysics is, in my view, the cornerstone of philosophical thought that develops in the West, and so the principle of non-contradiction thus becomes the element that will guide all subsequent philosophical discussion.

I will not address here the modern and contemporary objections to the principle of non-contradiction, for the intention of the approach I make is not to deny or defend it, but to expose the philosophical tangle to which it belongs. In this sense, I anticipate that the main objective of the return to Book IV of Metaphysics is only a resource for understanding how the fundamental axioms of Western thought, the predicative structure of logical utterances, and the quest for an ultimate essence of things form, in Aristotle, a single element that can be designated as the base that founds Western philosophy. I also note that the incisive character of the focus that I present in this analysis is justified by the need to present a counterpoint to the approach I shall follow, of corresponding questions found in Indian and Chinese traditions.

Metaphysics proposes, on the one hand, a synthesis of Pre-Socratic and Platonic philosophy and, on the other hand, a direct and systematic criticism of Heraclitus and, as I said earlier, this fact is not secondary. On the contrary, it offers us precisely the key to understanding the central question being posed: the impossibility, for Aristotle, of admitting the axiomatic character of impermanence and, consequently, the categorical negation of Heraclitus's fundamental thesis that states that everything flows. We do not have with Aristotle the first blunt criticism of the idea of movement as the principle of all things, as Heraclitus had thought, for Zeno of Elea had already demonstrated the paradoxical character of this thesis. What Aristotle's Metaphysics presents as unprecedented is the junction of the demonstration of the axiomatic character of the negation of movement with the predicative structure of logic and the consequent conclusion of the necessity of the existence of an element not subjugated to the rules of impermanence, of an engine that puts everything in motion, but that is not moved by anything.

In this perspective, and as a counterpoint to the reflections on impermanence, ontology and logic, which are developed in the East, I reiterate the character of predication of the structure of Aristotelian logic that establishes what I generally designate predicate logic, which in turn would be the only possibility of issuing valid and true logical-epistemological judgments about the world and, at the same time, the secure possibility of reaching the ultimate substance, the essence of all things, which is not under the yoke of movement: “Consequently, essence is the principle of all things, as is the principle in syllogisms: in fact, syllogisms proceed from the 'what is', and here in this case generations proceed from the 'what is'"(Aristotle, 2005, p.57).

In order to escape from the Sophist traps of the impossibility of issuing any logically valid and true judgment on the world, Aristotle, in Book IV of Metaphysics, takes as an initial reference, for the construction of his argumentative framework, the need to arrive at axioms. This text of Aristotle is, initially, the exposition of the necessity to define axioms in philosophy, as had already been done in mathematics and later, what would be the necessary instruments for the acquisition of such axioms, and finally, the definition of the principle of non-contradiction as being the first axiom of philosophy. It is essential to emphasize that Aristotle himself warns us that the moment of the acquisition of axioms in philosophy does not correspond to the initial moment of the act of philosophizing itself and that the search for axioms is already inserted in the dynamics of philosophical thought and already presupposes certain acquisitions: one of them is the presupposition of certain valid argumentative forms. Aristotle warns us of the basic need to know the syllogistic rules for the acquisition of philosophical axioms.

The quest to establish the basic principles, ultimate substance, and essence of things can only be carried out by those who master the basic rules of thought. It opens here a line of reflection on the question of the precedence of certain acquisitions to reach later ones. This central problem for Aristotle's philosophy is, however, secondary to what is discussed here. The central question for the comparison between the originating bases of Western and Eastern thought is the precedence of the syllogism for the acquisition of the axiomatic character of the principle of non-contradiction. We thus have the logical format below as a prerequisite for the acquisition of the main axiom of Aristotelian (Western) philosophy.

A is B

B is C

A is C

Aristotle's argumentative course towards overcoming the idea of the axiomatic character of movement, therefore, the affirmation of the impossibility that something can be and not be at the same time, is based on the syllogistic structure of logic and is one of the pillars of predicate logic. The principle of non-contradiction seeks to establish the bases that allow discernment of the various forms of substance, as we see in Book VII of Metaphysics, and ultimately to define it as the ultimate essence. We thus have an inseparable junction between syllogism, the principle of non-contradiction, the definition of the various forms of substance and essence as the system that allows Aristotle to overcome the project of Heraclitus, which affirmed the primacy of impermanence.

To discuss, therefore, the bases of Western thought, it is necessarily to return to one of the most decisive moments of the Greek clash, which would have definitively supplanted the axiomatic character of impermanence and affirmed the supremacy of a permanence (I) in the face of the horror of the putrefaction of the body itself. "Heraclitus's argument, stating that everything is and is not, seems to make everything true and this is not possible. Either something is, or it is not! In fact, there is something that always moves that which is moved, and the first that moves is itself immobile" (Aristotle, 2007, p. 34). In this way, as in China and India, Greece sets in motion what is now called philosophy, that is, it structures an intrinsic relation between logic, ontology, language and truth, with the basic purpose of solving the great problem of universal philosophy: the horror of the consciousness of I in the face of its own finitude.

Emptiness and Dependent Co-Origination in Nāgārjuna

One of the most important philosophers of the Eastern tradition is the Indian Buddhist monk Nāgārjuna, who probably lived between the first and third centuries of our era. His importance is due to several reasons, but I emphasize as principal a) the fact that he is the first systematizer of a consistent logical-philosophical structure that explains central questions of Buddhism; b) being the systematizer of what is denominated Mahāyāna Buddhism, which is one of the main bases of Zen Buddhism, and c) finally being the founder of the Mādhyamika School, Middle Way, which is an anti-metaphysical reaction to "eternalist" and "nihilist" perspectives strongly present in the Buddhist traditions of his time, especially the Sarvāstivāda monks.

Regardless of the controversy over the degree of importance of Nāgārjuna for Chinese thought, it is not possible to disregard the second motif mentioned above, which is the attribution to him of the main systematizer of one of the two foundations underlying Zen Buddhism which cannot be disregarded as an important contribution to the consolidation of Chinese Buddhism and what is denominated as neo-Confucianism.

With Nāgārjuna we have an instigating possibility of interlocution with the foundations of Western philosophy, which were presented to us in their most systematic form with Aristotle's Metaphysics, particularly with the principle of non-contradiction set forth in Book IV, and this confrontation between these two thinkers is, in my view, the clearest feasible possibility of understanding some central points that give us access to the fundamental differences that underlie the two largest constructions of what we call Western Philosophy and Eastern Philosophy. Unlike Aristotle, Nagarjuna presents us with a line of reasoning that aims ultimately to demonstrate the inexistence of an ultimate substance, an essence, a nature of its own that is the unshakable guarantee of the possibility of the permanence of something, before the overwhelming character of the dominion of movement over all things. The affirmations of the nonexistence of an ultimate substance, of its own nature, and of the interconnection of all elements of the physical world and concepts do not appear in Buddhism for the first time with Nāgārjuna, but rather the systematically clear and logical form of these two aspects and the interdependence between them, are presented to us by him in his main work titled Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way (Nagarjuna, 2016).

It is important to note that every theoretical construction of Buddhism, including the overwhelming desubstantiation of the Nagarjuna method, is a response to the central problem that arises with the perception that the putrefaction of bodies can also reach my “I”. Suffering, more specifically the great suffering in the face of the perception of finitude, is the starting point, also, of Buddhism and the philosophy of Nagarjuna.

The path of the Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way aims to demonstrate that it is not possible to find anything that can be defined as the ultimate substance, or self-nature (Svabhāva) that guarantees any kind of permanent independence to any entity or concept. The demonstration of the nonexistence of any possible permanent independence Nagarjuna denominates Sūnyatā, emptiness, which in turn is also a synonym of Pratītyasamutpāda, dependent co-origination and the methodological (soteriological) process of access to the unit between dependent co-origination and emptiness, as the founding elements of any kind of reality is the same: tetralemma below:

This argumentative structure is present in every work and appears directly exposed in only a few of them, as can be seen already in the first of all, where the author introduces as the central question the deconstruction of the principle of causality from the above tetralemma, which applies to the four causal possibilities of any being, phenomenon, and to any other possible things which may vindicate the necessity of some type of original cause. When affirming the impossibility of defending any of the four logical possibilities of a statement, in affirming that there is an equivalence between neither x, nor not x, nor x or not x, nor not (x or not x) or nor not (x or not x), Nagarjuna seems to convince us of the impossibility of asserting anything about the world and concepts, and is therefore a radical skeptic. However, the objective of the logical resource employed by him is to demonstrate the impossibility of asserting any independent existence, any ultimate substance, essence or nature of its own, consequently any kind of cause that subsists on its own. In this sense, any statement aimed at substantiating the thesis of the existence of something that puts everything in motion, but is not moved by anything, is radically abandoned because it leads to error.

In asserting the nonexistence of any ultimate substantiality of all things Nagarjuna does not advocate the inexistence of the things themselves, he does not postulate some kind of nihilism or any convention concerning the world. In demonstrating the inexistence of Svabhāva and the consequent relationality of everything, Nagarjuna could not say that such a thing would not exist substantially, but only conventionally. This statement seems to be as problematic as any claim rejected by Nagarjuna himself. The assertion that there is no ultimate substance does not allow one to conclude that something does not exist in any way unless one takes substantiality as an existential criterion, but what Nāgārjuna does is precisely to demonstrate the logical error arising from assuming substantiality as an existential criterion and the devastating consequences of such presuppositions.

The relationality that founds, therefore, the character of existence of a world not made up of ultimate substances is, in turn, a relationality devoid of substantiality. The relationality that presupposes the existence of substantiality is what I call relative relationality and, on the other hand, non-substantial relationality, devoid of any logical or ontological link with any trace of substantiality, is what I call absolute relationality. This distinction is fundamental to the understanding of the set of changes proposed by Nagarjuna, when he states that things are devoid of substantiality, that they are empty, which means the same as affirming that they are in a dependent co-origination relation based on the nonexistence of any ultimate substance. The presupposition of substantiality is the founding element and at the same time the basic constitutive element of a logic which presupposes the ontological distinction between the subject and the predicate of the statement. In this perspective, any relational statement can be ultimately reduced to a predicative statement and its relational character would thus be only relative to a still later moment and therefore still reducible to the axiomatic moment, prior to the relational, and would be necessarily predicative.

Empty and Full in Laozi

The bases of Chinese logic are already present in some way in the main classical texts, but it is in the I Ching, Book of Changes where they appear in their initial form and later with Laozi and Zhuangzi where they assume their most elaborate format. Their bases are very distinct from what was produced in Ancient Greece and the India of Nagarjuna, but it is fundamental to emphasize that argumentative structures close to these two strands of thought also existed in Ancient China, where we find logicians such as Huizi and Kongson Long who can to be inserted in the group of philosophers who, in both China and India, participated in the initial period of structuring their respective logics.

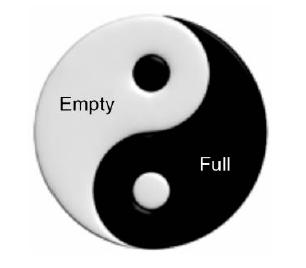

Unlike Aristotle and Nagarjuna, Laozi does not refer directly to the traditional paradigm of movement to address the issue of impermanence, but rather to a relational reference that allows inferring the inexistence of any substantialization, including time itself. The logical structure of the Daoism of Laozi is present in every Chinese philosophical tradition and is expressed, in its clearest form possible, in the shape of the figure that characterizes the Yin and Yang. These two terms can be considered the element that ensures the thread of what can be termed in general “Chinese thought,” for it is present in all of China's major lines of thought, from the I Ching to the foundations of modern Chinese philosophy. Yin and Yang designate the complementary character of everything and of all things, and to the extreme, designates an absolute relationality present at all levels of a network composed, in turn, by basic elements containing the same model.

To exemplify the logical character of this basic structure and its non-substantialist and non-essentialist assumptions I turn to Chapter 11 of Dao De Jing, where we have one of the most elucidating passages of a Chinese text on the relational character of Yin and Yang, present in all things. In this chapter we have not a treatise on the ultimate constitution of things, on the appearance and the essence of phenomena, we do not find in this text a reflection on the logical structure of the arguments, as we have in the School of Logic with Huizi and Kongson Long, we have a seemingly infantile, "non-philosophical" format, a plastic format that seems to disregard the intellectual competence of the reader, who instead of treatises receives allegories. Let's go to the text:

thirty spokes make up the middle

in the unmanifest (無 - 有) the use (有 - 用) of the vehicle

molded clay makes the jar

in the unmanifest (無 - 有) the use (有 - 用) of the jar

chisel out the doors and windows for the house

in the unmanifest (無 - 有) the use (有 - 用) of the house

therefore

using the manifest (有) useful is the unmanifest (無).

(Laozi, 2002, XI)

I refer here to the translation of Dao De Jing by Mario Bruno Sproviero, but I insert some original ideograms in the translated text to better elucidate some aspects, which I believe are central to this text. Chapter 11 is basically composed of four parts: three arguments and one conclusion, but, as I said earlier, it purposely presents an allegorical format. The first argument has as reference a wheel, the second a container, a jar or a cup, the third a house and finally we have the conclusion, but all three arguments have the same structure that can be defined by the terms translated by Sproviero as "unmanifest," "manifest," and "use." Here we have the key to understanding the relational logical character of this text and the presence of Yin and Yang in their argumentative basis. Chapter 11 contains three key ideograms that are: wu 無, you 有 and yong 用 and their respective combinations among each other. Wu 無 is one of the most important ideograms in Chinese philosophy and later a key “concept” in Chinese thought: it means “nothing” and is one of the possible characters that form negative phrases; you 有 is one of the possible characters that can be translated as “being,” yet it has a predominantly existential meaning, and can be translated as “to have” and “to exist;” finally we have the yong 用 ideogram that can be translated here as “use,” “put into practice” and “employ.”

“Thirty spokes make up the middle, in the unmanifest use of the vehicle.” The thirty spokes of the wheel come together and form its middle, its hub, but it is the inexistence of something that is its wu you 無 有, translated by Sproviero as "unmanifest" that makes it an artifact that can be used in a useful way, which makes the you yong 有用 of the car. Maintaining due clarification, we might well translate wu you 無 有 here as "not being", which is precisely the emptiness of the middle of the wheel, which allows the insertion of the axle and makes the wheel, a wheel. The complementary relationship between the emptiness of the middle and the filling with the axle is the most elemental exemplification of the complementary character of Yin and Yang. I do not fear here a question about the "essence" or "ultimate substance" of the wheel, but rather an allegorical exposition of the complementary relationality between "empty" and "full", in a perspective that aims at the functional character of the vehicle and, consequently, the radical refusal of substantial resources. The following arguments of the container and the house are enlargements and clarifications of the same logical line.

The formation of predicate logic in the ancient Western world is directly linked to the elaboration of a particular conception of I, of subjectivity, of an individual that I come to call, in an extremely general form the atomic individual, as well as the formation of I, subjectivity and the individual in China is directly linked to its logical-philosophical relational tradition, which also founds what I denominate the relational individual. This perspective of analysis presupposes the thesis that there is a thread6 that runs through the so-called Middle Ages and consolidates itself in Modernity in its most elaborate format, which is precisely the focus of interest of this analysis: the formation of the bases of the modern atomic individual and the inseparable link of these bases with predicate logic. The Chinese thread is, in my view, easier to be followed, since it only presents a radical change of course with the revolution of 1949. This fact does not ignore the transformations that occur in the history of Chinese thought, but indicates the millennial presence of its Confucian, Daoist, Buddhist, and forensic bases.

The analysis of the historical-philosophical construction of what I call here the atomic individual has as one of its main purposes the demystification of the idea that the project of Western modernity is a rupture with its own tradition, the dissolution of the idea that modernity and tradition in the Western world are exclusive poles. On the contrary, it is only possible to understand important aspects of the elements that characterize the modern individual, as the consummation of the Western tradition itself, for the atomic individual is not a totally original creation of its own independent, unrelated epoch. It is the very consummation of a historical-philosophical project and is therefore within its own tradition, and cannot be understood without it, that is, it is a traditional element. This elementary aspect assumes a central importance in this analysis, since its transposition out of the West means the substitution of one tradition for another. We thus have, with the clash over the replacement of the Chinese relational individual by the Western atomic individual, a controversial dispute between two traditions.

The starting point for this topic is therefore the assertion that there is a guiding thread linking the first philosophical reflections on the constitutive elements of relational logic and the formation of the atomic individual in Ancient Greece, especially Aristotle, to the fundamental ideas that support the concept of the atomic individual from modernity, specifically from English liberal thinkers such as Mill and Locke and also from the liberal, German idealism of Hegel. This restricted circumscription of the scope of analysis of the constitution and formation of the concept of the atomic individual to a few and, chronologically, such distant thinkers is sufficient for the purpose here established, since it allows us to understand precisely the core, the basic elements of the formation of this individual, from its initial logical-metaphysical constitution in Aristotle, of its formation as a search for an ultimate substance, which would allow us to determine what causes something to be what it is, that is, to determine what would be the ultimate element, its essence, indispensable for the constitution of this individual, for his "concrete" constitution in modern thinkers such as Mill, Locke and Hegel, who insert the triad of individual liberty, private property and civil law, as the bases that extend the concept of a Greek individual, of ultimate substantiality and definitively found what we call here the modern atomic individual.

The rupture with the bases of the metaphysical character of the formation of the Greek individual and the religious character of the individual in the Middle Ages occurs with the transposition of the idea of ultimate substance into the realm of human nature and its basic constitutive element, which is individual freedom. However, modernity arises precisely with another rupture. The abandonment of the idea of a human theological metaphysical freedom for the realization of individual freedom in private property, in its unpublished format, inaugurates modernity. The free man is the owner, first owner of the land. The atomic possession of the land as private property thus becomes the first possibility of realization of the substantial character of the modern atomic individual, and the next step to ensure the permanent realization of ownership is the elaboration of legal rules, a right that guarantees ownership and transfer of ownership.

As in the West, China, in its history, constructs a conception of the individual from its philosophical foundations that go back to its first philosophical theories, more than two and a half centuries ago. Before moving forward and addressing more precise questions about the basic differences in the formation of the Western atomic individual and the Chinese relational individual, I present a possible objection to the kind of analysis I am presenting here. It could be argued that these conceptions of individuals could in no way be explained in a unitary way and probably never fully realized in the daily lives of the Chinese and Westerners; this is due to several elementary factors, of which I point out only one that I consider to be more relevant to this analysis. An interlocutor could claim that there is an abysmal distance between the world of philosophical theories and norms and rules governing people's daily lives in both the West and China, and therefore no philosophical reflection on the relationship between different types of logic and the formation of individuals could be taken as a reference for the understanding of "concrete life", the everyday life of simple people and their social relations.

The analysis I am presenting here is exactly the opposite of this objection. I emphatically affirm the impossibility of understanding the clash between the relationship between modernization and tradition in China today, without an understanding of the historical / philosophical bases underlying the formations of the concepts of individuals in the West and China. With this I also present a thread as a possibility for a better understanding of the proximities and distances of the formations of societies in the West and China, for however diverse the different societies in the Western world are, it is always possible to recognize in all of them, fundamental elements that characterize the "isolation" of what I call the atomic individual and, on the other hand, however diverse the regional cultures in China, it is always possible to detect fundamental elements that characterize the "relation" of what I call the relational networked individual.