Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.17 no.2 Uberlândia mayo/ago 2018 Epub 01-Mayo-2019

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v17n2-2018-7

Articles

The Diccionario de Pedagogía by Labor, Barcelona (1936): the iconic-textual construction of a pedagogic discourse linked to the ideals of the “New School”

1 Doctor en Filosofía y Ciencias de la Educación (Universidad de Salamanca). Profesor Catedrático de Hª de la Educación en la Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. E-mail: anton.costa@usc.es

2 Doctora en Educación (Universidade de Santiago de Compostela). E-mail: mariaeugenia.bolano@usc.es

The important Editorial Labor of Barcelona, which had so much dissemination with its various bibliographic collections in Spain and in Latin America between 1920s to 1980s, was responsible for the editing of two notable Diccionarios de Pedagogía (Pedagogy Dictionaries), one in 1936 and another in 1964, both created from two different educational assumptions; in one case, from those belonging to the New School (1936) and the other from the so-called neo-scholastic and Catholic assumptions, as shown in the comparative contrast that is undertaken here. The contribution also takes care of the references to education in Brazil that are set out in the 1936 text.

Palabras: Diccionario de Pedagogía Labor; New School; Pedagogic Discourse; Dictionaries; Sánchez Sarto

La importante Editorial Labor de Barcelona, que tanta difusión obtuvo con sus diversas colecciones bibliográficas en toda España y en Latinoamérica entre los pasados años veinte a ochenta del siglo XX, fue responsable de la edición de dos notables Diccionarios de Pedagogía, uno en 1936 y otro en 1964, elaborados ambos desde dos distintos supuestos educativos; en un caso, desde los propios de la Escuela Nueva (1936) y en el otro desde los supuestos neo-escolásticos y católicos, como se manifiesta en el contraste comparativo que aquí se realiza. La contribución se hace cargo, además, de las referencias a la educación en Brasil que se exponen en el texto de 1936.

Palabras: Diccionario de Pedagogía Labor; Escuela Nueva; Discurso Pedagógico; Diccionarios; Sánchez Sarto

A importante Editora Labor de Barcelona, que obteve grande difusão em suas diversas coleções bibliográficas em toda Espanha e na América Latina entre as decadas de 1920 e 1980, foi respopnsável pela edição dos notaveis Diccionarios de Pedagogía, um em 1936 e outro em 1964, ambos elaborados a partir de distintos ideais educativos; de um lado, a partir da Escola Nova (1936) e, de outro, a partir das ideias neo-escolásticas e católicas, como se manifiesta no estudo comparativo que aqui é realizado. A contribuição também aborda as referências à educação no Brasil que estão expostas no texto de 1936.

Palabras: Diccionario de Pedagogía Labor; Escola Nova; Discurso Pedagógico; Diccionarios; Sánchez Sarto

On Dictionaries and systematic works of Pedagogy

The set of the intellectual preparations developed in the field of education and pedagogy, in particular, in the German cultural space from the mid-19th century under the combined influence of Kant, Pestalozzi, Herbart and Froebel, had a recognised importance for the preparation of pedagogy treaties and manuals, of their history and on teaching in the various European state nations, in the USA and Latin America. In this regard, it is suffice to recall the contributions for the Spanish case of Mariano Carderera,6 author of the equally important Dictionary of education, or those of Pedro de Alcántara García,6 or also, among others, those of Rufino Blanco y Sanchez6, in this case already belonging to the first moments of the 20th century.

In this line, we should point out the intense preparation that took place from the end of the 19th century in the field of manuals for History of Pedagogy/History of Education,6 and a similar intellectual line which made possible the creation of Pedagogy Dictionaries, a complex undertaking, in which the Dictionary to which we will refer to here participated and that again has an important German influence, as can be seen in the indicative list of

Pedagogy Dictionaries, edited prior to the 1940’s, which we attach here:

Münch, M. C. (Ed.) (1841‒1842). Universal Lexicon der Erziehungs und Unterrichtslehre. Augsburg (third edition: Augsburg, 1859-60).

*Palmer, Ch., Wildermuth, J. D., Schmid, K. A. (1859‒1878), Encyklopädie der gesammten Erziehungs und Unterrischsmefens. Gotha (Germany), 4 vols.

*Rolfus, H., Pfister, A. (1863‒66)). Real Encyklopãdie der Erziehungs und Unterrischsmefens. Mainz, 5 vols. (Second edition: 1872‒74; supplement, 1884).

Campagne, E. M. (Ed.) (1869). Dictionnaire universel d’éducation et d’enseignement. Bordeaux (Third edition, Paris, 1873)

Vogel, A. (1881). Systematische Encyklopädie der Pädagogik. Eisenach.

Buisson, F. (Dir.) [Part 1 générale (vols. 1-2), part 2 special ou practique (vols. 1-2), 1878‒1887]. Dictionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. París: Hachette. Rein, G. W. (1895‒1899). Encyklopädisches Handbuch der Pädagogik. Langensalza: Beyer, 7 vols. (Second edition: 1903‒11, 10 vols.).

Martinazzoli, A., Credaro, L. (1910). Dizionario ilustrato di Pedagogia. Milán: Casa editrice Francesco Vallardi, 3 vols.

Laurie, A. P. (Ed.) (1911‒1912). The Teacher’s Encyclopedia of the Theory, Method,

Practice, History, and Development of Education at Home and Abroad. London, 7 vols (second edition: 1922, 4 vols.).

Buisson, F. ( Dir.) (1911). Nouveau dictionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. Paris (new edition: 1939).

Monroe, P. (1911‒13). A Cyclopedia of Education. New York, 5 vols. (Second edition: 1926-28).

*Roloff, E. M., Wilmann, O. (1913-1017). Lexikon der Pädagogik. Freiburg: Herder, 5 vols. (second edition, 1921)6.

Watson, F. (1921-22). The Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Education. London: 4 vols.

Schwartz , H. (Ed.) (1928‒31). Pädagogisches Lexikon. Leipzig,4 vols.

Nohl, H., Pallat, L. (Eds.) (1928‒33). Handbuch der Pädagogik. Berlín, 5 vols+supplement.

Marchesini, G. (1929). Dizionario delle Scienze Pedagogisce. Milán: Società Editrice (2 vols.)

*Spieler, J. (1930-1932). Lexicon der Pädagogik der Gegenwart. Berlín: Institut für wissenchaftliche Pädagogik (2 vols.)

Verheyen, J. E., Casimir, R. (1939-1949). Paedagogische Encyclopediae. Amberes: De Sikkel (2 vols.)

(*: Indicates that these four great German dictionaries include, together with the Dictionary by Labor which we will discuss here, the bibliographic legacy of the Galician inspectors Manuel Diaz Rozas/ Cristina Pol)6.

El Diccionario de Pedagogía by Sánchez Sarto and Editorial Labor

We find the Barcelona edition of an exceptional Pedagogy Dictionary in this generic academic and editor context. It should be noted that since the end of the 19th century the city of Barcelona was experiencing a strong climate of general modernisation and a growing social concern for educational development, with unique and innovative expressions in this regard,6 whether we talk about some innovative teaching centres or refer to the Escola de Mestres Joan Bardina or Escoles d'Estiu6 that were organised from the Mancomunitat de Catalunya for this training. This strong climate was also accompanied by social contradictions and conflicts and a vast mobilization of various professional and cultural sectors. In this framework we can refer to the Editorial Labor of Barcelona, for its contributions in the field of education sciences and to the Pedagogy Dictionary edited at this publisher under the careful and critical direction of Luis Sánchez Sarto.

As Conrad Vilanou6 and José Martínez de Sousa6 have written, Labor was founded in Barcelona in 1915 by the young German Georg Wilhelm Pfleger Hoffmann in collaboration with Dr. Josep Fornés i Vila, dedicating themselves to the preferential publishing of scientific and technical books (medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, engineering, trade). The editor, who frequently travelled to the Leipzig Book Fair, would contract the rights for Spanish edition of a part of the Pedagogy works that he saw edited in German there, channelling that edition, through the "Library of cultural initiation” collections, divided into twelve sections, promoted and organised by Manuel Sánchez Sarto - which came to publish more than four hundred titles, and the "Contemporary Pedagogy” collection. "This was how as Conrad Vilamou says, the knowledge of very important6 German authors in the educational field was spread among us, and by extension to Latin America, although it also integrated Spanish authors (among others José Mallart, Domingo Barnes or Xohán V. Viqueira), which culminated with the Spanish version of the Pedagogy Dictionary, this time, directed by Professor Luis Sánchez Sarto, a formidable text that tuned in with the educational project of the Spanish republican generation", thus achieving that between 1925 and 1937, a high quality doctrinal corpus was published, in which the five possible following sections can be distinguished:

Theoretical construction of Pedagogy in its historical and systematic dimension.

Work of a psychological nature, with a dual experimental and pedagogical aspect.

Issues related to "work education", vocational guidance and the psychotechniques.

Questions of a medical, hygienic and therapeutic nature.

Work in experimental pedagogy, didactics and school organisation.

The Dictionary is composed of two large-format volumes (26.5x18), with more than 3250 columns of information (something more than 1600 pp.) to accommodate a total of 980 document entries (conceptual, nominative, topographical), very often supported with valuable references of an international scope, which in this way convert the Dictionary, due to its systematic zeal, into a suitable instrument that serves to present and manage educational culture, unparalleled in Spanish culture until the penultimate moments of the 20th century.

Its editing meant, Herrero et alii6 indicate, an enormous effort of updating knowledge related to education at a moment in history where the momentum of pedagogical renewal was one of the progressive signs of identity of the Second Spanish Republic’s governments (19311936, 1939), as well as an effective effort to open up to the most modern European scientific and philosophical currents.

The edition includes a detailed alphabetical index of subjects and authors, an analytical index (with breakdown and remission of concepts), diverse diagrams (particularly those that allow the management of almost 60 national education systems that are included to be seen) and a set of 100 photographic prints, which usually accompany its illustrations in the thematic issues addressed, as we will state further on.

111 teachers and researchers participated in its preparation, who are in an initial list of names, accompanied by their professional performance and place of performance. For this reason, we can detect the participation of 40 Germans and Austrians, 43 Spanish, 18 Americans (Latin Americans in particular) and 10 authors from other sources. Among those of Spanish authorship we should cite Margarita Comas, Ricardo Crespo (of the New Daimon School, of Barcelona), Alexandre Galí, Anselmo González, Santiago Hernández Ruíz, José Llongueras, Adolfo Maillo, Emili Mira, Ana Rubiés, Ruíz Amado, Concepción Saiz Amor, Leonor Serrano, Domingo Tirado Benedi and Antonio Vallejo Nájera, that is to say, professionals of notable recognition in the 1930s, especially in the Hispanic educational field.6 Other well renowned contributors are: Alfredo Aguayo, Faria de Vasconcelhos, Lourenço Filho, Alois Fischer, Afranio Peixoto or Anisio Teixeira. In this regard it is noted in the foreword that: "The depth of content is guaranteed by the vast, brilliant core of domestic and foreign contributors who have been involved in its drafting."6

In this regard, scholars have spoken of the German origin of this Dictionary at various moments. So, Conrad Vilanou said: "Originally published in German;" on the other hand, Julio Mateos points out:

Among its almost one thousand entries is an exhaustive list of Germanic authors, as well as concepts, experiences, organisational models or institutions of the same origin. It is no coincidence that the Dictionary was first published in German, as Labor has a large number of contributors in Germany and another in Spain with qualified translators specialised in different pedagogical subjects. In the thick Spanish edition, public education in Germany was dealt with at the time, and the general trend of the work was rather conservative.6

Also Lorenzo Luzuriaga, who strangely does not participate among the 111 contributors of the Dictionary, the Pedagogy Dictionary that he directs from Buenos Aires and in the Losada publishers’ one of 1960, he maintains that the Dictionary by Labor was based on the Lexikon der Pädagogik edited by Roloff.6 Carried by the concern to know what really might have been in the previous ones, we investigated the issue through various channels. Taking advantage of the presence in Santiago de Compostela of the bibliographical legacy of the Galician inspectors Manuel Díaz Rozas/Cristina Pol, which contains among other books the various German Dictionaries of Pedagogy, to which we referred earlier, we have been able to resolve some questions: in fact, this Dictionary by Labor has as its antecedent a German dictionary, that of Spieler, J. (1930-1932). Lexicon der Pädagogik der Gegenwart (2 vols.), not Roloff's as has been written, but it should be noted that only 40 authors out of the 196 present in the Spieler Dictionary remain in Labor’s Dictionary, which speaks of the very remarkable authorial renewal present in it: 60 different contributors, including now some of Ibero-American origin.

Two very notable dimensions present in the Dictionary’s text are those referring to the voice-authors included, - about whom notable information, framing and bibliography are given-, and to the countries, about which information is provided on their respective educational systems and developments; with a total of 40% of the textual entries in the Dictionary. There are 156 authors examined in the first volume and 180 in the second, i.e. a total of 336, 85% of the total being European: 102 Germans, 43 Spaniards, 42 French, 29 Italians, 22 English, 12 Swedes, 10 Belgians, 6 Portuguese, 4 Czechs and Bohemians, 2 Dutch, 2 Austrians, 2 Russians, 2 Hungarians, 2 Greeks (Plato and Aristotle), 1 Croatian, 1 Polish and 1 Swedish. Among the American authors are 10 North Americans, 10 Chileans, 7 Cubans, 6 Argentines, 6 Mexicans, 6 Brazilians, 2 Paraguayans and 1 Bolivian.6 None from other continents, with the sole exception of India (R. Tagore).

If we talk about the countries we note the following: there are 61 entries, of which just over half (N=31) are equally allocated for countries in both Western and Eastern Europe; 21 of them are destined for the Americas (in addition to Canada and the USA, 19 IberoAmerican countries), 2 for Africa (one together and the other for Egypt), 6 for Asia (China, India, Japan, Afghanistan, Palestine and Turkey), in addition to one for Latin America as a whole, one for Australia and one, with extensive treatment, dedicated to Catalonia.

We should note that the entries that have a historical contextualization (mainly the voiceauthors) obey to a greater extent to contemporaneity: in 43% of cases they are between the 19th and 20th centuries; in 34% of cases they belong to the 19th century, and in 16% of cases they are in the Baroque and Enlightenment period. Only 16 entries are located before the 16th century.

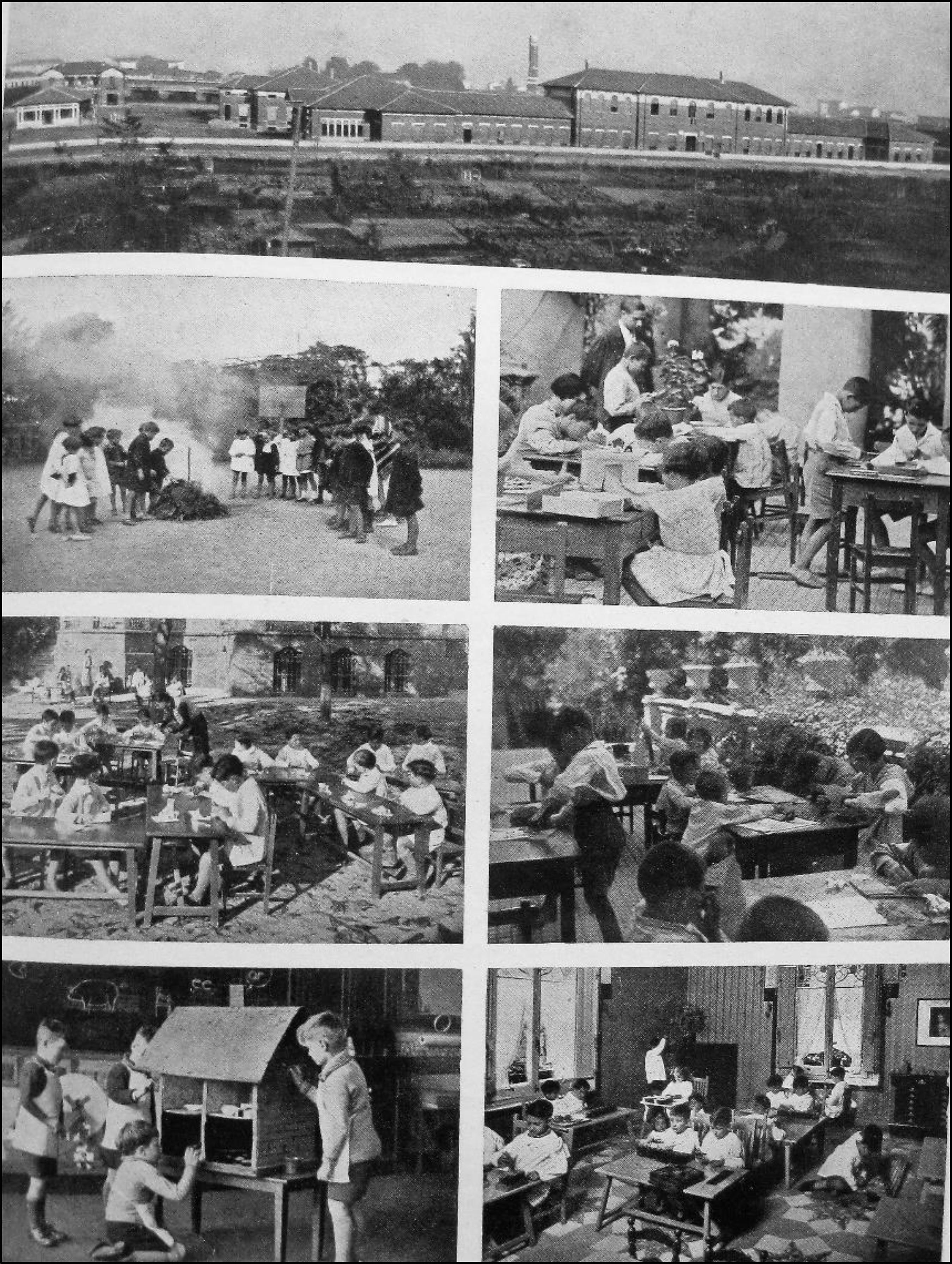

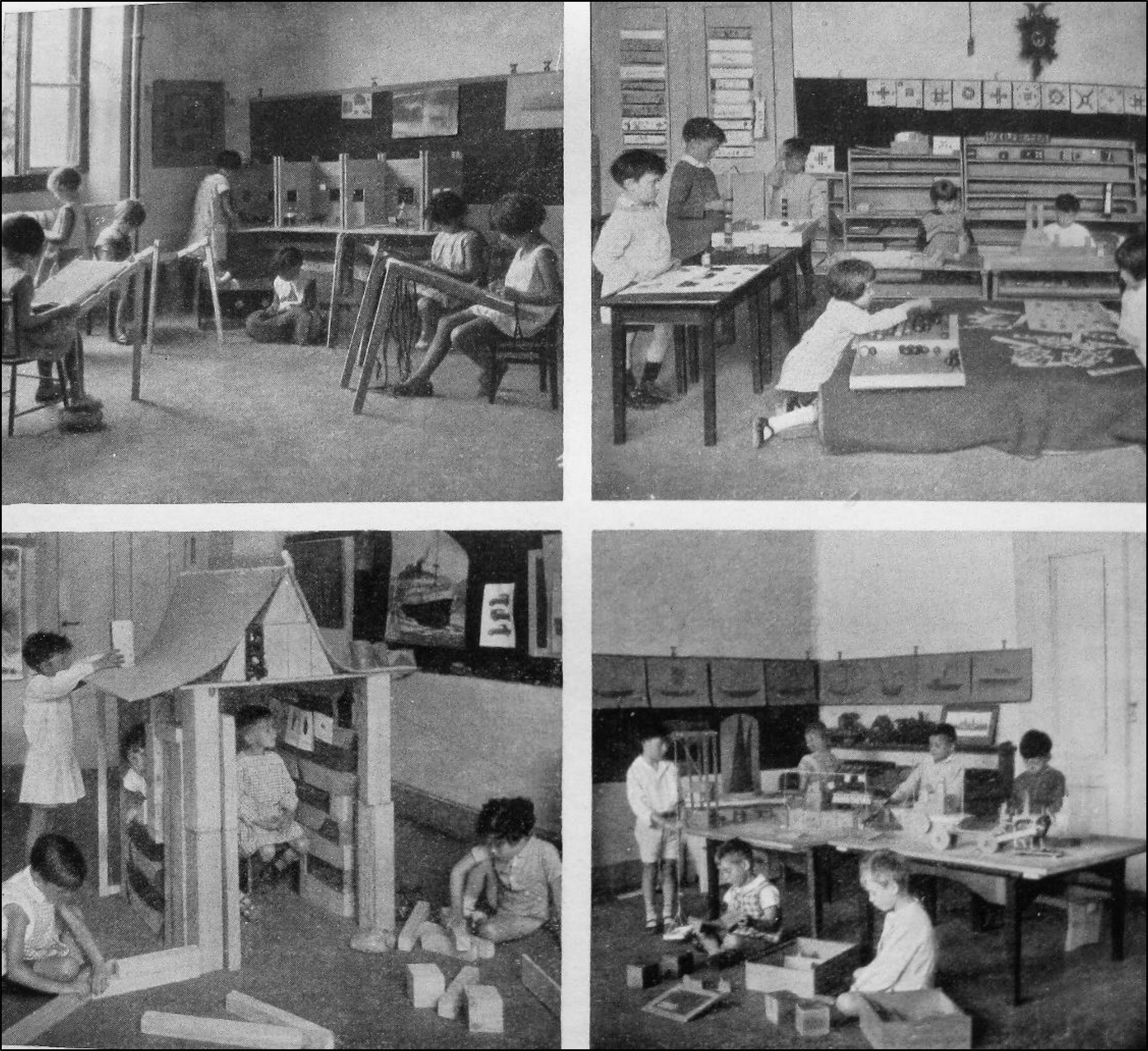

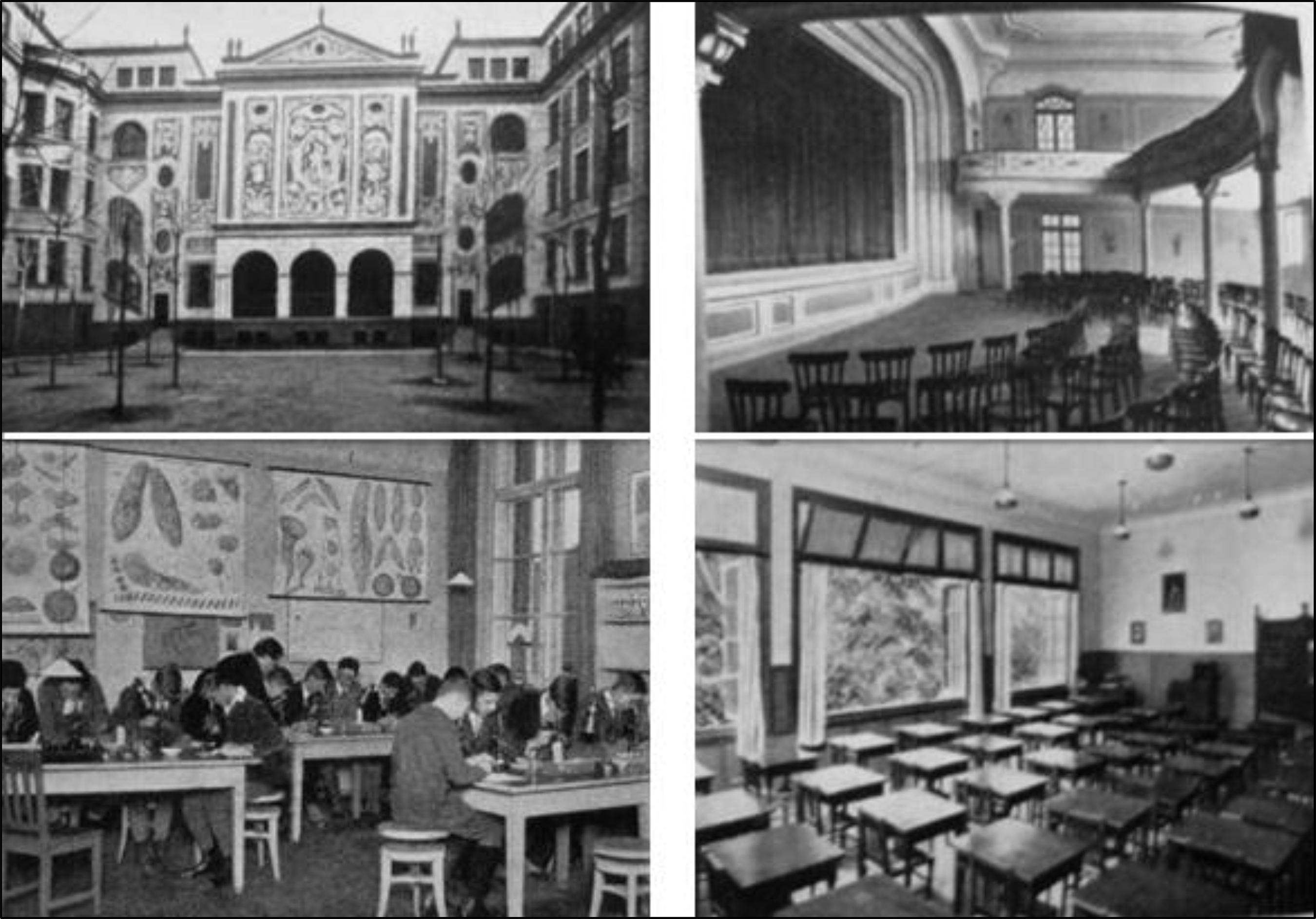

It is necessary to bring attention to the presence among its pages of 104 slides (bundle and back of 52 sheets) containing more than 700 photographs (B/W) that try to bring readers closer to an exceptional archive of iconic notes on the world of education, which as such could form a 'pedagogical discourse', which is worth observing and valuing as such: a discourse that manifests itself propitious to the most beloved ideals for the international movement of the New School, while presenting educational realities with a broader spectrum, given their link to the textual repertoire of the Dictionary.

A (re)presentation of the New Education?

We could say so positively. In this regard, in the same Dictionary, New Education is defined as that which brings together the following notes:

Respect for the child's personality

Principles of self-activity and school community

Coeducation of the sexes

Extra-confessionalism or school neutrality,

Active methods

Another note on New Education is provided in the Dictionary: "functional education", that is to say, all knowledge, according to Claparède, has as its own function the satisfaction of a need or desire in which the action of the individual has its origin, so that the learnings imply a functional activity to achieve knowledge with meanings for the individual.

Indeed, we can note that the Dictionary shows, without a doubt, a greater love for a naturalist, positivist, realistic and pragmatic pedagogy; a pedagogy based on pedagogical activism as a reaction to formalism and intellectualism. In addition, structuralism is affirmed as a model in terms of the psychology of learning and not in terms of associationism. On the other hand, we can also observe a clear departure from the Neo-Thomistic philosophical orientations (with a sought-after interrelation between religious faith and human reason) and metaphysical ones, which, on the other hand, will be present in the Pedagogy Dictionary directed by Victor García Hoz in the same publishing house of Labor in 1964:6 Here we detect a clear metaphysical-theistic conception of educational phenomena, in such a way that beyond a naturalistic, pragmatic or sociological purpose to education, there is a moral purpose and mission based on a Catholic religious teleology.

Labor’s Dictionary of 1936, in turn, presents reflections from philosophical pedagogy; these are fundamentally ascribed to a pedagogical orientation of values6(under the influences of Kerchensteiner and Spranger, with their axiological and ethical-ideal claim to culture), and to the idealistic, Neo-Kantian6 and Marburger perspective traced by Natorp,6 doing so by distancing themselves from the idealist/neo-idealist spiritualism positions, claimed in Italy by Gentile and later assumed in Spain as a support for national-catholic pedagogy. In this regard, Vilanou has written:

As an alternative to the normative character of Herbartian pedagogy, Schleiermacher opted for a hermeneutic pedagogy that favours the interpretation process between theoretical discourse and educational practice, and this orientation was recovered during the Weimar Republic, with the professorships in Pedagogy being extended throughout Germany....giving way to a Germanic version of the New School, which tried to link education to culture, emphasizing the formative dimension of the educational process [with reference to the bildung, our own], thus also demanding an aesthetic-moral education. Between 1924 and 1933, the movement of pedagogical reform (Reformpadagogik) expanded, especially in dialogue with the neohumanist pedagogical tradition, which emphasized moral culture. Perhaps it was this orientation that opted for a culturalist pedagogy that most influenced the Spanish reformers.6

There is a decantation in favour of the Active School in the Dictionary , "which takes as its starting point the psychology of the child and prepares for life by extracting school matters from life itself (column no. 1173)", respecting the child's personality, introducing community work and vivifying the school by means of exercises in practical life, as Montessori advised. In terms of Luzuriaga: “activity as the basis of education, based on psychological, social and pedagogical reasons",6 so that the school "must mobilize the activity of the child; it must be a laboratory rather than an auditorium", Claparède said.

By the way, the Dictionary shows its distancing in the entries "Philosophy and Pedagogy" and "Purpose and Ideal of Education" that it was "witnessing a resurrection of the metaphysical system of German speculative idealism, which tried to create a metaphysical education system, guided by the Neo-Kantian theory of knowledge, being an expression of it, for example, Krieck's theoretical elaboration, which also rejected Herbart's individualistic normative pedagogy, but considered the whole of cultural reality and social forms under the prism of a metaphysical educational idea.

This being so, we are dealing with a well thought-out cultural and pedagogical artifact that condenses numerous socio-historical keys. It is situated well beyond a given and correct commercial bookseller/editor product. It is part of a 'publishing programme' supported by specific sectors of opinion and academic-pedagogical orientation. And this leads us to turn our gaze towards the little-analysed figure of Luis Sánchez Sarto and his family of Republican intellectuals. It is necessary to place Sánchez Sarto in one or more networks of interinfluences and in a field of conflicts and cultural creations to better understand and interpret the meaning of this artefact.6

A reading by contrast: From the Dictionary of 1936 to the Dictionary of 1964 (1970)6

The Pedagogy Dictionary directed by García Hoz in the same Labor publishing house is constructed, - as indicated in its Prologue - from a "radical unity of approaches", taking into account the "peculiar situation of Pedagogy, between Philosophy and Positive Sciences:"6 thus, the notions of purpose, perfection, evolution, intentionality, which are essential for the understanding of the educational process, are radically philosophical concepts, - it is arguedwhich justifies the presence of philosophers' names in the Dictionary, while there are other terms that, on the other hand, start from the positive sciences. At the same time, the Dictionary wants to take into account the multidimensionality and breadth of the concept of Educational Sciences and to unite pedagogical research and educational work - which are separate, it is indicated, and must be united.

In this Dictionary there are 1514 terms or entries that are defined and delimited. A greater number of entries than in the 1936 Dictionary, but it is almost always done in a much more concise way. The 1970 edition contains 214 more entries than the first edition of 1964, providing conceptual and terminological updates and also some bibliographical updates, "with selective priority given to information on Spain and Spanish-speaking countries", the Editorial Note accompanying this second edition states.

In this case, 117 contributing authors are involved (with a greater number of authors than in the 1936 Dictionary), the vast majority of whom are Spaniards6 linked to the educational and administrative field (in particular, education inspectors) and to academic pedagogical institutions.

The number of voice-authors is reduced to a total of 259, although the predominance of the authors examined from Germany is maintained, with a total of 67. These are followed by Spain with 35, France with 27, USA with 18, Italy with 15, Great Britain with 14, and Switzerland with 12. Only eleven other countries have some pedagogical figure in the Dictionary, with a total of only 21 entries.

“Disappearing” from this Dictionary, in comparison with that of 1936, are figures as prestigious as those of Roberto Ardigó, Frantisek Bakule, Bovet, De Sanctis, Demoor, C. Freinet, Profit, Bertrand Rusell, Alexis Sluys or R. Steiner and among the Spaniards Ainaud, Altamira,6 Amorós, Bartolomé Cossío, Mira López, Rodolfo Llopis, Joaquin Xirau, and Zulueta, and although many others still retain a reference, we are generally faced with schematic treatments, as in the case of Claparède, for example, although in some others the treatment is more generous in the extent and information given (e.g., Cousinet, Decroly, or Dewey, but is often done with evaluative judgements that include some partial condemnation, through De Hovre's6 constant and scrutinizing eyes)

We can see that entries have disappeared as meaningful as those of: child-friendly (socialist side), school associations (such as the Red Cross Youth in Spain), student autonomy, Catalonia, school community, pedagogical working communities, school cooperatives, Esperanto, sexual ethics, eugenics, Board for the Expansion of Studies, secularism, struggle for the school, pacifism, neo-idealist pedagogy, positivist pedagogy, pacifist pedagogy, revolutionary pedagogy, socialist pedagogy, sexual pedagogy, pedagogical reform, radical reformers of the school, or socialist (Education and Pedagogy).

The 1964 Dictionary takes up Pope Pius XI's condemnation of naturalism in his Divini illius magistri ( V. II, p. 658) for forgetting the Christian supernatural formation of youth, highlights the neo-scholastic movement - as a restoration of classical Christian philosophy - and criticises the Deweyian philosophical pragmatism (V. II, p. 729, and V. I, pp. 259-260) for their relativism, naturalism and radical sociologism, and for not finding in it a place for "transcendent truths and for leaving morality without foundation. It denounces "pedagogical activism" as "a chaotic system, given the imprecision and vagueness of the terms for activity and action" and as being "in part unacceptable principles for a Christian education" (V.I, p. 9). There is also a negative significance in the concept of "Single school" (unified) given its principle of obligatory nature, which puts the right of states before the right of families to the education of their children (previous in Christian doctrine), and therefore it also goes against the right of the Church.

Also observed in this Dictionary6 is an increase in the number of entries of psychological content and a reduction in the relative weight of those referring to strictly educational content: now, a different psycho-pedagogical orientation becomes evident, as we move from a basic psychology that was intended to support educational practices to a much more instrumental and applied psychology, while at the same time the educational practice sought its foundation not in psychology - as in the 1930s - but in scholastic philosophy.

Thus, the new Dictionary reflects a strong intellectual isolation, both in its contributing authors and in the thematic treatments. It was, however, the canonical and educator dictionary of the 1960’s and 1970’s in Spain, while the Labor’s Dictionary of 1936, to which no reference is made, and the one directed by Luzuriaga, remained only as teaching instruments within reach of few; an authentic wall of damnatio memoriae...impoverishing the dynamics of pedagogical change that were being experienced at that time.

The iconic discourse of the Pedagogy Dictionary (1936): Analytical description and interpretative considerations of the content of the illustrations according to the grouping categories.

Finally, we come to the moment of the analysis of the iconic discourse of the more than 700 photographic illustrations present in Sanchez Sarto's Dictionary. In this respect, we have constructed a possible categorisation that we show here.

Table 1 Thematic grouping of the illustrations

| N. | |

|---|---|

| History of Education (Global/ Rousseau/ Pestalozzi/ Fröbel/ Herbart/ Montessori) | 86 |

| States: Europe (Germany/ Belgium/ Catalonia/ Spain/ Great Britain/ Italy/ Portugal/ Russia/ Switzerland) America (Argentina/ Brazil/ Chile/ Cuba/ USA/ Mexico/ Uruguay) | 209 |

| Popular Education and Women | 23 |

| School buildings and classrooms | 21 |

| School furniture and equipment | 32 |

| Child Health, Development and Disorders (Care of breast-feeding children, Physiology of Vision, Physical Developmental Disorders, Infectious Diseases, Mental Health) | 58 |

| Institutional modalities of educational centres (Nursery education / Secondary schools / Teacher training colleges / Universities) | 49 |

| Statements of pedagogical activism (Children's drawings/ Handcrafts/ Rhythm/ School workshops/ School theatre/ School exhibitions) | 68 |

| Physical Education and Circum-School Institutions (Physical Education/ School Bathrooms/Colonies/ School Sanatoriums/Outdoor Schools) | 88 |

| Vocational guidance and training (Psycho-pedagogical devices/ Agricultural education/ Work schools) | 43 |

| Therapeutic Pedagogy and Special Education (Therapeutic Pedagogy / Deaf-Mute and Blind / Abnormal) | 34 |

| Didactics of physical and natural sciences. | 10 |

Source: Own elaboration from the recount and categorical grouping of the total number of photographic images present in the Dictionary. None of the questions cited as compositional units in each of the twelve categories has fewer than 6 photographs and it must be said that each question is usually presented in a range of 12 to 16 photographs, in some cases of 18.

Within the History of Education category, most of the illustrations are composed of photographs or other types of representation (pictorial, engraved) of the faces of authors representing the History of Western Education, with a strong presence of German authors. In the cases cited in Table 1 above in parentheses (Rousseau...Montessori), illustrations of some of the living spaces or centres created by the authors mentioned above or presentations of the teaching materials they created are also included.

The number of illustrations that we have grouped under the States category is high. In particular, they refer us to photographs of school buildings (from nursery schools to university faculties or pedagogical institutes), but also to classrooms, vocational training centres and to a lesser extent to images of school camps, library and laboratory rooms, manual work rooms, health care and psychological observation rooms, open-air schools, groups of pupils carrying out a certain body and physical activity, an educational cinema or hygienic facilities, so we could reduce the number of photographs included here and the relative weight of the category, although it has been thought that this could be the most 'transparent' and informative grouping, given that it allows us a transnational reading of the constructive conventions of the twenties-thirties of the past twentieth century, very marked, both by the hygienic recommendations and by the organisational criterion of class graduation, although this criterion appears visually nuanced due to the inflection of the active methodology with their favourable orientations towards individualisation and school-extra-curricular activities in variable groups of students.

In the "popular and women's education" category, the ten images referring to the Pedagogical Missions of the time of the Second Spanish Republic and the thirteen referring to the education of children and adolescents have been grouped together, with explicit references to "domestic work" and "domestic economy", and the dominant gender ideology, currently rejected, is noted here.

When referring to "school buildings and classrooms" we have grouped the four plates with 21 photographs that strictly speaking appear in the Dictionary in this way, although from what we have just said, they could be many more. With a marked preference for centres and facilities with explicit marks such as "renovating, models or experimental". Among others, there are references to the Scuola Rinnovata in Milan, the Berlin Forest School, the English Thomasson Memorial School, Bedales, Odenwald, the Instituto de Educaçâo in Rio de Janeiro, the Instituto de observación La Sageta in Barcelona, the Escola Industrial in Terrasa, the Instituto-Escuela and the Montessori School in Barcelona, the Giner de los Ríos, Pablo Iglesias and Cervantes groups in Madrid, the Calpe, Milá i Fontanals, Mutua Escolar Blanquerna and Pere Vila schools in Barcelona, the escola-bosc and the escola del mar in Barcelona, or the special education (abnormal) school in Madrid, among others. The diversity of spaces is evident: playgrounds, workshop rooms, drawing rooms, music rooms, laboratories, library rooms, canteens, work rooms...

With regard to "school furniture and materials", we would like to draw your attention to the presentations of Montessori furniture and teaching materials, various types of desks, Decroly and Descoeudres materials, among others.

The iconic representation of aspects related to medical health, anatomical-physiological development and medical disorders and problems is remarkable. We can detect the great influence of the Belgian Demoor or the Spaniard Tolosa Latour, by referring to two names of scholars for biology applied to education, to show their relevance, at a time when the eugenic concern for infant feeding and against medical infections was very strong among the reformist social sectors in the Western world, specifically in the field of teaching; in this respect, hard photographic images are not avoided with respect to some disabilities and situations of childhood illness. We must also bear in mind that in the grouping for "Physical education..." and "Therapeutic pedagogy..." categories we also find images that maintain a ‘continuity’ with those present in this category referring to "Health, development and disorders", in addition to approaching mental disability and the deficiencies of deafness and blindness.

In the "school modalities" category we have grouped together the two infant schools (kindergarten scenes), those that refer to secondary schools, those that refer to teacher training colleges and those that also refer to university centres, as well as images of buildings or classrooms and other rooms with different educational purposes, which include, for example, a practical lesson in natural history.

In the "statements of pedagogical activism" category there are many photographs that convey a message: learning by doing deweyano. There are very few photographs in which there are graduated classes with students seated at their desks and all seated in the same direction towards the teacher's desk; on the other hand, there are numerous others in which diverse groups of boys and girls appear either in drawing rooms and other manual works or artistic creations, in theatre exhibitions, expressing themselves physically and rhythmically... or in their creations through school exhibitions.

This could be added to the next well-represented grouping category that we have entitled "physical education and circum-school institutions": an anti-formalist and antiintellectualist call for physical education and body development as key dimensions of "integral education" (colonies, baths, open air...).

In addition, not only are some of the expressions of vocational training (agricultural and industrial) present, but also references to vocational guidance, which, very much in the spirit of the times, is reflected in the “psycho-pedagogical device” sheet, that is to say, the instruments that had generated the various investigations of experimental psychology in the Wundtian perspective, the 'brass psychology' to which Binet critically referred.

Finally, it should be pointed out that no fewer photographs can bring us closer to different expressions of the specific didactics, perhaps the most marked being those referring to the physical and natural sciences.

A panoramic consideration of this group endowed with an appreciable systematicity, if we are able to detach ourselves from the weight of the monumentality of the images referring to the great school buildings, it is possible that it will allow us to 'compose' pragmatically, that is, interpretively by us, a repertoire-archive-discourse on the New Education, in a similar sense to what was probably a desideratum of the publishers: to show scenes, that could make up an insight of what a vivified education should mean.

Many of the illustrations and photographs could be of a different type, more representative of the empirical reality of the school in the 1930s, and in other hands the illustrations would be others. It is true that in this case there would be a communicative textimage break. However, in this plausible look that the publishers propose to us, it is possible to appreciate the traces of an underlying discourse, a certain codification, a certain rhetoric of images6 and an explicit intention of social visibility, between reality and desire, of a New Education: it is possible to perceive some aroma and a certain imaginary of this New Education.

An observation of education in Brazil

The Dictionary of 1936 dedicates the informative columns 459 to 476 to Brazil, which is accompanied by illustrations and some other illustrations in which we can see a group of teachers doing practical laboratory work, samples of teaching agriculture and also outdoor education, photos of the school Prado Junio de Rio, a sample of material for the germination study in a Brazilian school, students from the Rio Branco school in Sâo Paulo carrying out a geographic didactic project, a school dental assistance office in Sâo Paulo, a photo of the Uruguayan school group in Rio, one from the library of the Maria José de Sâo Paulo school group, one from the Instituto de Educaçâo and one from the Central Library of Education. The information, which refers to some historical background, draws attention to the influence of French culture, more recently modified by combined German and American influences, and seeks above all to present "the current situation": the lack of official impulses for a national education policy highlights the role of particular initiatives, such as the impetus given by the Brazilian Association of Education (ABE) with its five congresses held between the one in Curitiba in 1927 and the more recent one in Niteroi in 1932 and its promotion of the ideals of the New School.

The information reviews the different levels of education: the almost absent preschool education, limited to brief institutions in Sâo Paulo and Belo Horizonte with some other essays, almost always linked to some teacher training colleges; the presence of school graduation in urban groups, the significant and recent increase in enrolment, the overload of curricula and their more literary character are highlighted; it was pointed out that most teacher training colleges did not have the "rigorous character of technical-professional institutes", although the creation of the Institutes of Education and Schools of Pedagogical Improvement such as the one in Minas Gerais "entrusted to Swiss and French technicians" was highlighted; the reform of secondary education is noted by the 1931 provisions and some other information is available on university institutions and vocational and special training schools. On the other hand, it is stated that "a climate of social reconstruction and the demand for education is being experienced", from the reforms of Ceará in 1923 to those of Sâo Paulo in 1931, pointing out the importance of the actions developed by the ABE and also of the Manifesto of 1930, collective expression of the impulses of the New School in Brazil, where the ideal of the "single school" is expressed: "Reforms should contribute to the rapprochement of social classes and the formation of a more just human society, and should aim at the organisation of a unified school, from kindergarten to university, with a view to the selection of the most suitable.

The entry for Brazil noted here also indicates some bibliography (texts by Peixoto, Sodre and Leâo) and the presence of the magazines Nova Educaçâo, Escola Primaria, Escola Normal and Annaês do Ensino.

In our present time, attentive to the recovery and study of the historical-educational heritage that gives us so many keys to a more adequate understanding of the pedagogical past of our environments and societies, it is worth taking into consideration what some pedagogy dictionaries mean as places of memory and formalisation of pedagogical knowledge. Windows for historical understanding.

REFERENCES

Carderera, M.(1855). Diccionario de educación y métodos de enseñanza. Madrid: Printed by A. Vincent, 4 vols. Its third edition, corrected and considerably augmented took place between the years 1883 to 1886. [ Links ]

3Carderera, M.(1855). Diccionario de educación y métodos de enseñanza. Madrid: Printed by A. Vincent, 4 vols. Its third edition, corrected and considerably augmented took place between the years 1883 to 1886.

4Alcántara García, P. de (1878). Teoría y práctica de la educación y la enseñanza: curso completo y enciclopédico de pedagogía expuesto conforme a un plan rigurosamente didáctico. Madrid: English y Gras Editores. Second edition significantly reformed and augmented, Madrid: Librería de Hernando y Compañía, 1902-1905.

5Blanco y Sánchez, R. (1907-1912). Bibliografía pedagógica de obras escritas en castellano o traducidas a este idioma. Madrid: Typography of the Revista de Arch., Biblib. Y Museos, 5 vols.

6Costa Rico, A. (2015). La manuales de Historia de la Educación a examen. En Colmenar, C. y Rabazas, T. (eds.). Memoria de la educación. El legado pedagógico de Julio Ruiz Berrio. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, pp. 143-174.

7This important Dictionary would be later renewed by an edition of four volumes, taken into consideration as the starting point for the Italian Dizionario Enciclopédico di Pedagogia from S.A.I.E. de Torino, 1958-59, most recently published in 1972.

8Costa Rico, A. (1998): “La biblioteca que guardaron las gaviotas: memoria bibliográfica de dos inspectores republicanos”, Historia de la Educación. Revista interuniversitaria, 17, pp. 445-451.

9Decades ago this was highlighted by the prominent educational historian Jordi Monès (1977): El pensament escolar i la renovació pedagógica a Catalunya (1833‒1938). Barcelona: La Magrana, and on this issue Joan Soler Mata returned with new arguments and data (2015): “La renovació pedagogica durant el segle XX. La cruïlla catalana: dinamismes i tensións” in Soler Mata: Vint mestres i pedagogues catalanes del segle XX. Un segle de renovació pedagogica a Catalunya. Barcelona: Rosa Sensat. Also González Agapito, J. et alii (2002): Tradició i renovació pedagógica. 1898‒1939. Barcelona: Publicacions of l'Abadia de Montserrat.

10Expression in Catalan equivalent to "Summer Schools": a space for teacher training through workshops, courses and conferences, which took place in Barcelona.

11Vilanou Torrano, C. (2005). "Joaquín Roura Parella (1897-1983) and the origins of University Pedagogy in Catalonia", in Ruiz Berrio, J. (ed.), Pedagogía y Educación ante el siglo XXI. Madrid: Universidad Complutense, pp. 171-202, in particular, pp. 187-190. In this regard Vilanou notes the role of Joaquin Xirau Palau in the implementation of the Seminari de Pedagogia of the University of Barcelona, the forerunner to the creation in 1933 of the Education Section of the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, as an example of the innovative educational climate that Catalonia was experiencing, contemporary to the impulses of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (Free Teaching Institute) in other areas of the Hispanic geography.

12Martínez de Sousa, J. (2005). Antes de que se me olvide: una aventura tipográfica y bibliológica personal e intransferible. Gijón: Trea.

13With respect to the German influences in Spain we can consider: Hernández, J. M. (coord.) (2009): Influencias alemanas en la educación española e iberoamericana (1809-2009) Salamanca: Globalia Ediciones Anthema; Marín Eced, T. (1990): La renovación pedagógica en España (1907-1936): los pensionados en pedagogía por la JAE. Madrid: CSIC; Hera, J. de la (2002): La política cultural de Alemania en España en el periodo de entreguerras. Madrid: CSIC.

14Herrero, F., Ferrándiz, A., Lafuente, E., Loredo, J. C. (2001).«Psicología y Educación en la II República in the Spain of Franco through the Diccionario de Pedagogía by Labor (1936, 1964)», Revista de Historia de la Psicología, vol 22, nº 3-4, p. 379.

15All of them renowned figures, some from the Catholic reformer field, and to a greater extent belonging to sectors of progressive liberalism and socialism. Several of them will develop their professionalism in different areas of Latin America from 1936, as a result of Franco's military coup of that year and the civil war until the spring of 1939, resulting in an important cultural and political exile.

16Incidentally, the planning process followed is explained in the same place: a nomenclator was created on the basis of a systematic division, grouping in it the various topics, before proceeding to an alphabetical division of entries, bearing in mind the scientific bases of education, the initiation into all theoretical principles, the solution of practical problems, as well as the history and present of Western pedagogy. The nomenclator has the following broad categories: culture and education; educator and learner; forms, means and methods; analysis of school institutions; curricular analysis (with presentations of the most important special teaching methods in primary schools); Pedagogy as a science, with its basic, auxiliary and special expressions; the organisation of public education and references to the life and work of the greatest educators.

18Mateos Montero, J. (2011). «Huellas pedagógicas alemanas en España. Una aproximación histórica», Magazín (digital), 20, p. 30.

19Luzuriaga, L. (1960, 1962). Diccionario de Pedagogía. Buenos Aires: Losada (Printed in Spain in Talleres de Ariel, Barcelona). See. entry «Bibliografía pedagógica», p. 55. In addition, its foreword written in 1959 states, perhaps with some impropriety to mute the Dictionary of Sánchez Sarto: "It is based essentially on new educational ideas. We currently do not have a Dictionary of modern pedagogy, originally written in Spanish. Those that exist in our language are adaptations or translations of foreign works. This Dictionary aims to make up for this lack and does so in a concise and synthetic manner....giving preference to the essential pedagogical topics or those that are of greatest interest today".

20Among them, the Brazilians Abilio C. Borges, Lino Coutinho, Lourenço Filho, Ruy Barbosa, Sampaio Doria and Anisio Teixeira; the Argentines Manso de Noronha and Bernardino Ribadavia, the Cubans Saco, Valdés Rodríguez, Varela and Morales, Varona, Aguayo and Sánchez, José de Anchieta, and Guerra Sanchez, the Mexicans Rodríguez Puebla and Castellanos, the Chileans Molina Garmendia, Riquelme Rodríguez, José Abelardo Nñez, Salas Merchán, Amunátegui, Fernández Peña and Casanueva Opazo, the Bolivian Donoso Torres, the Paraguayan C. Baez.

22Education, in addition to intellectual and character formation, should pursue the formation of a personality made up by a specific value-consciousness.

23Let us remember that Kant advocated an education of children in accordance with the 'idea of humanity' that he claimed as the basis of his ethical-moral construction.

24Opposed to Herbart's individualistic and intellectualist idea, in giving education a social character: according to Natorp, education, which is guided by ideas, is both individual and social.

25Vilanou, C. (2005). «Weimar en España» en Guereña, J.L., Ossenbach, G., Pozo, Mª del M. (Dirs.). Manuales escolares. Madrid: UNED, pp. 87-107.

27Perhaps an observation of those who had been the Spanish authors in the field of education published in Labor since the mid-twenties, of those who were the translators of pedagogical works into Spanish and of those who are the Spanish contributors that may help to raise some hypotheses. The greater weight of "academic professionalism" on other relevant considerations would seem to be apparent, but this is something that needs further study.

28The Pedagogy Dictionary directed in 1964 by García Hoz had a second edition in 1970, on which we made our analysis.

61Adolfo Maillo, a contributor to the 1936 Dictionary, by the way, does not now appear among the contributors.

62Of whom, however, it is said in the 1936 Dictionary..: "The Spanish teaching profession considers him to be the true representative and promoter of educational reform in Spain".

63In the Dictionary directed by García Hoz, direct and indirect references to De Hovre are constant. De Hovre, F. (1946). Pedagogos y pedagogía del catolicismo. Madrid: Fax, and De Hovre, F. (1951) Pensadores pedagógicos contemporáneos (Includes the text “Estudio de los pedagogos contemporáneos españoles” by María Ángeles Galino). Madrid: Fax.

64Herrero, F., Ferrándiz, A., Lafuente, E., Loredo, J. C. (2001).«Psicología y Educación..op. cit., p. 379.

Received: September 01, 2017; Accepted: December 01, 2017

texto en

texto en