Initial considerations

In February 1934, the student Nicolino Murino signed the first page of his book entitled Letture di Religione (Readings on Religion). Nicolino was a 3rd grade student in the Instituto Manzoni2 in São Paulo. The common notations of Nicolino3 and the book survived for decades and arrived at the present time bearing investigative possibilities for the field of History of Education. The present text is a result of the study “History of school cultures in Italian schools on Brazilian soil (1875 - 1945)”, funded by the CNPq. The aim of this extract is to analyze production, circulation, and strategies of (con)formation put in play by two volumes of the book Letture di Religione, distributed free to students in Italian schools in Brazil.

The two volumes of Letture di Religione are part of a set of textbooks produced and sent free for distribution to students of “Italian schools abroad”, as ethnic schools were called in the fascist period. Books for reading, arithmetic, geography, homeland history, songs, literature, and others were sent. In this text, the investigative view centers on analysis of the two volumes of Letture de Religione, works written and compiled by Giuseppe Fanciulli, an important Italian author for children’s and youth literature at that time. The first volume is directed to the second and third grades, while the second is directed to the fourth and fifth grades.

Anchored in Cultural History references, the empirical corpus is composed of textbooks, legislative measures, and consular reports; documentary analysis is the methodological procedure that directs the investigative view. The text was organized in three sections. The first contextualizes Italian schools abroad, with a focus on the case of Brazil, and their relation to fascism and the Catholic Church. The second presents a brief biography of the author of the books under analysis. The third focuses on production, the material aspects of the works, and their circulation in Italian schools in Brazil.

1 - Italian schools abroad, Fascism and the Church

In previous texts, I have affirmed that the schooling process among immigrants that left the Italian peninsula and established themselves in Brazil between the end of the nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century experienced ethnic schools in the different states in which they resided (Luchese 2012, 2014, 2015). In general, we can say that immigrants sought out public schools, but because of the difficulties faced by the Brazilian government itself in offering schools in sufficient number and conditions for these population contingents, they themselves opened ethnic schools. Thus, “in different spaces, in a plurality of conditions, in a broad process of negotiation, tension, and dispute, which was also contingent on diverse provincial legislation, [...] they produced and were produced by educational practices that were markedly ethnic” (LUCHESE, 2014, p. 17). In the states of Espírito Santo, Pernambuco, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul, records are found of ethnic schools opened in rural areas, many of them community schools, and also ethnic schools maintained by mutual assistance associations, in general in urban areas. Furthermore, parochial and private schools were opened with ethnic features. According to data presented by Parlagrecco in 1906, shown in the following table, there were 171 Italian schools that served more than ten thousand students, a relatively small number compared to the number of immigrant children and youth and descendants, yet a number that cannot be ignored.

Table 1 Italian schools in Brazil - 1905 - 1906

| State | Italian schools | Total students |

|---|---|---|

| Pernambuco | 1 | 35 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 3 | 316 |

| Espírito Santo | 4 | 200 |

| Minas Gerais | 4 | 277 |

| Paraná | 7 | 526 |

| São Paulo | 92 | 6,131 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 28 | 1,941 |

| Santa Catarina | 32 | 1,519 |

| Total | 171 | 10,945 |

Source: FANFULLA, 1906, p. 800 - 802.

A few year later, in 1908 for example, students numbered 13,657, who attended 264 Italian schools, 13 of them Catholic (MINISTERO, 1908). From 1870 on, Italian schools abroad were under the responsibility of the Italian Foreign Ministry. Therefore, the consular network was responsible for systematically sending reports that revealed the conditions of Italian schools in various countries with the presence of emigrants. Consuls were also responsible for receiving and distributing schools materials (especially books) and financial subsidies, which, with oscillations, were sent to various countries that relied on Italian schools.

When Italian Fascism began, the organization and attention to Italian schools abroad intensified. Specific legislation regarding selection and production of books and teaching material to be distributed free to students became frequent. A single didactic-curricular organizational structure and requirements regarding teachers and their skills were standardized. The books that had been sent and distributed in the consulates since the end of the nineteenth century increased in volume and qualification. As Salvetti (2009) highlights, the main Fascist action in relation to subsidized Italian schools was sending new textbooks permeated with fascist ideology. The two volumes of Letture di Religione written by Giuseppe Fanciulli are approved and produced in this context.

The approval, production, sending, and circulation of religious reading books to Italian schools abroad was not a common event prior to Fascism. They were a product derived from a coming together of the Catholic Church and the Fascist State. This is not to generalize by considering that all those who were members of the Catholic Church adhered to fascism or vice-versa, but to consider that “Catholics initially received fascism relatively well; they were enthusiastic about it at the time of the Lateran Treaty and lost a bit of their enchantment when the totalitarian and racist aspects and the alliance with Nazi Germany arose” as Bertonha states (2001, p. 354). Fascism represented discipline, order, and social justice. It is fitting to recall that the cordiality of Pope Pius XI toward Mussolini and fascism facilitated the agreement established in 1929, the Lateran Accords. Catholicism and fascism, which were contrary to liberalism and communist expansion, joined together, but that did not occur in a simple and unequivocal manner. The recognition of the Catholic religion as the religion of the Italian State made the Church and its schools, newspapers, and parishes available to fascism. This was not a uniform process, but the conservatism of many Catholics abetted their coming together. As Mussolini himself indicated, Catholicism could be used for Italian expansion, that is to say, fascist expansion. Upon analyzing the relationship between fascism and Catholicism, Giron stated:

[...] there was an exchange between Fascism and the papacy; the Church received the favors of recognition of a State within the Italian State, and the Italian State received the consent of the Church City-State regarding the regime in power. This exchange favored the Church, which could remodel its financial empire, while Mussolini could make use of the Church organizational machine, both in the parishes and in the publishing sector and means of communication. (GIRON, 1994, p. 75)

The negotiation that put an end to the “Roman Question” recognized the principle of full power and sovereign jurisdiction of the Supreme Pontiff over the territory of the Vatican. In addition, the Italian State made compensation with a sum of money for the old provinces and goods lost by the Catholic Church in Italian unification. Moreover, a concordat was established that regulated relations between the Church and the State. For its part, the Holy See manifested that the Roman Question was definitively resolved and it recognized the Kingdom of Italy in its formation and constitution. As Cannistraro and Rosoli (1979) affirm, the Church and the Italian State made reciprocal concessions.

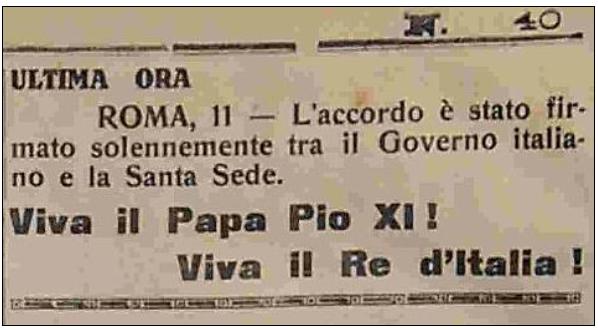

The signing of the Lateran Treaty and the end of the Roman Question was intensely commemorated among the immigrants and their descendants in Brazil. The pages of newspapers hint at its importance and provide a glimpse of the festivities celebrating the agreement. The negotiations had been followed by several periodicals, especially those published by religious congregations in Brazil. For example, La Staffetta Riograndense4, only two days after the signing, already published a note celebrating the treaty, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: La Staffetta Riograndense newspaper, 13 Feb. 1929, p. 2.

Figure 1 Note spreading news of the signing of the Lateran Treaty

In the following edition, the joy of the news of the end of the Roman Question was highlighted on the first page, fully transcribing the text of the treaty in Italian and its main effects. Figure 2 shows the first page headlines.

Source: La Staffetta Riograndense newspaper, 20 Feb. 1929, p. 1.

Figure 2 Front page of the La Staffetta Riograndense newspaper

The identification of many clerics with fascism5 was related to the struggle against communism and liberalism; many of them had adhered to or admired fascism even before the end of the Roman Question. In regard to the Italian Colony Region of RS, Giron states that:

Even before 1929, when the Lateran Treaty was signed, the influence of Fascist Italy was felt among the clergy. In 1923, D. Pedro Rota, superior of the Salesians, brings good news from “Young Italy”. In 1924, Dr. Celeste Gobatto is elected to the Administration of Caxias, which makes the clergy rejoice: a true Fascist assumes the government of Caxias. (GIRON, 1994, p. 88)

In the interpretation of the same author, the Catholic Church in the Italian Colony Region of Rio Grande do Sul was essential in political organization and in organization of the immigrants and “was the institution that most promoted fascism”. (GIRON, 1994, p. 87). The Diocese of Caxias in Rio Grande do Sul was created through dialogue of representatives of the community (especially Celeste Gobatto) and of priests of the colonial region with the Vatican and was, above all, the desire of Archbishop of Porto Alegre, D. João Becker, himself, as Giron analyzes (pp. 87-93). However, Rio Grande do Sul was no exception. Cardinal D. Sebastião Leme of Rio de Janeiro exhibited esteem for Italy and for Il Duce on various occasions, as did the Archbishop of Porto Alegre, D. João Becker (BERTONHA, 2001).

For the Italian immigrants and their descendants, especially those that lived in more distant rural areas, the clergy was one of the most powerful bearers and disseminators of fascist ideas. In addition, it should be considered, as Valduga (2007, p. 157) states, that fascism modeled itself as the “bastion of morality and hard work and prides itself on the activity of its children abroad, the highest example of the value of its people”. Furthermore,

Exaggerated patriotism was a new and gratifying sentiment; the disadvantaged immigrants out of their country found a greater meaning in their work recognized by their country. The immigrants were transformed from unknown members of a colony to the symbol of useful and productive labor. Italy opened its arms to its long forgotten children, and they recognized it as their country and recognized themselves as Italians. (GIRON, 1994, p. 109)

Trento (1989), Giron (1994), and Bertonha (2001) agree that adherence to fascism occurred in a much broader way among the middle class and bourgeoisie. For the vast majority, as mentioned by Trento (1989), admiration for Il Duce may have been greater than understanding of fascism as a project and political-ideological action, since Mussolini represented a discourse and a practice of valuing emigrants from “greater Italy”, which “had no inconsiderable weight in its function as propaganda” (TRENTO, 1989, p. 304). Thus, Italian nationalism, as a feeling of identification, the basis for formation of identity, was frequently understood as equivalent to fascism.

Sending of leaflets and books, film exhibitions, conferences, festivities, the founding of the Italian-Brazilian Institute of High Culture in Brazil, and funding trips of Brazilian journalists to come to know the “deeds of Fascist Italy” are some of the cultural propagators listed by Bertonha (2001) in spreading fascism. In addition, putting on Italian works in Italian in important theaters such as the Municipal Theater of São Paulo, in spite of the lack of prestigious Italian tour companies, is notable. Trento (1989) reports the case of Ruggiero Ruggieri in 1929. Another cultural aim was the creation of the publishing company Sociedade Editora Latina by Rubbiani and Stevanoni, directed toward publishing in Italian or Portuguese or both (Trento, 1989). For Bertonha “in regard to Brazil, Italian documentation reveals a relatively low interest of Fascism in disseminating its works and its doctrine among Brazilians” (2001, p. 272), especially in relation to the 1920s. For the same author, in the 1930s, “this situation changed substantially, and the effort of disseminating fascism grow in a notable manner” (BERTONHA, 2001, p. 274). The Sociedade Dante Alighieri should have emerged as the leader of fascist propaganda, but in 1937 it had only 150 registered members in the city of São Paulo, and for Trento (1989, p. 299) “not even in the past had it ever left great vestiges of itself”.

There was propaganda of fascism for immigrants and descendants, especially by Italians who immigrated after the First World War, who together with the consuls, led the founding of newspapers6, the organization of festivities and celebrations, radio programs, the fascios7, the dopolavoro8, the opening (or reorganization) of schools, the offering of language and Italian culture courses, and theater shows and musicals, in short, the entire structure that, as Trento states, sought to raise consciousness of belonging to “Italians abroad”

In addition to the attempt to maintain Italianism alive and to infuse an ideology in the children of Italians, the efforts of the mother-country in the period between the two World Wars were directed toward ensuring a greater intellectual presence capable of influencing local culture, whether through broader dissemination of Italian production or through sending university professors or even creating the schools themselves. (TRENTO, 1989, p. 299)

Many ceremonies and collective activities had the presence of Brazilian supporters since “with rare exception, the Brazilian political class was quite indulgent in relation to the regime” (TRENTO, 1989, p. 305).

A look at the production and circulation of books sent to Brazil for the purpose of disseminating and forming an ideal of “Italians abroad” and of educating them for the work and the religiosity that were the watchword of Italianism, now directly related to fascism, leads to observation of the author of two works focused on in this text: Giuseppe Fanciulli.

2- Giuseppe Fanciulli: the author and his works

Montino (2009), in his study on Fanciulli, states that he was a rapidly forgotten author. Yet, he was an author that dedicated himself intensely to children’s and youth literature in “serene and sweet” tones, who produced a vast work committed “to a nationalist ideology to which had had unreservedly offered his pen, later linking himself to fascism” and, by means of this attachment, coming to be part of the set of intellectuals that “magnified the regime and Il Duce, and that, beyond the ideology, adhered to the conservative idea of mother-country that nationalism had fortified as a result of the Great War” (MONTINO, 2009, p. IX). In the specific case of Fanciulli, his Catholic faith permeated most of his activities, whether as writer or journalist. As Montino (2009) recognizes, mother-country and faith were central foundations of his intellectual thought.

Giuseppe Gaetano Giulio Fanciulli9 was born on March 8, 1881, in Florence (Firenze). His parents were Giovanni and Enrichetta Guidotti. He lost his mother at seven years of age and remained under the care of his two aunts. He graduated from the Regio Istituto di Studi Superiori Pratici e di Perfezionamento with a degree in Philosophy in 1906, when he was 25. In the same year, he earned a Law degree. In 1909, he obtained a teaching certificate from the Università Popolare Di Firenze. As a scholar of Psychology, in 1929 he obtained professorship in Psychology from the Università Di Firenze and also from Milan (Montino, 2009). He published articles and works with themes connected with emotional life in childhood. He began his professional career as a journalist in 1906 and, in different newspapers and under several functions (correspondent, copywriter, director, collaborator...), he was linked to journalistic activity throughout his life. His experience in the Giornalino della Domenica, directed by Luigi Bertelli (known as Vamba), was decisive. For Montino (2009), Fanciulli’s journalistic work regarding childhood was what led him to children’s literature.

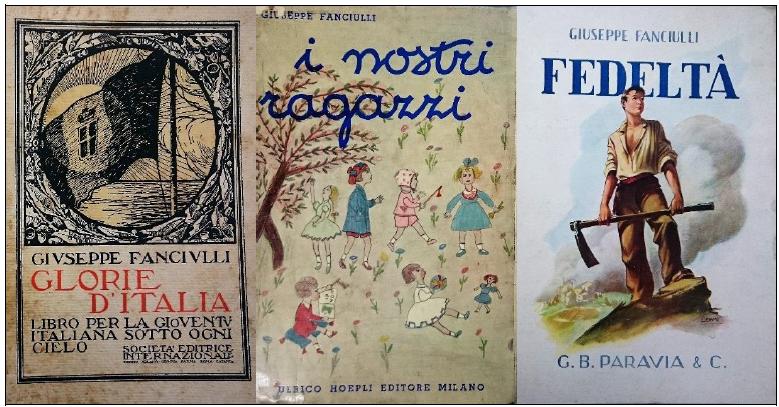

Giancane (1994) considers the combined works of Fanciulli, with more than 150 books, one of the largest contributions to Italian children’s literature. In a similar direction, Montino (2009, p. XIV) evaluates that Fanciulli was “one of the most widely known and penetrating voices of the pedagogical vocation of literature for children in the first half of the 1900s”. The combined works of Fanciulli were created around the values of nation, of collaboration between social classes, of paternalism, of good feelings, and of an urban and bourgeois view of the world (MONTINO, 2009). The modernity of Fanciulli was in the various fronts he also mobilized for action, as he published books, wrote for newspapers and theater, and participated in radio programs. Montino (2009, p. XV) states that the “vast pedagogical works were placed at the service of a certain idea of Italianism, and, even more so, a certain 1900s need to educate the masses and to instill discipline from the time of childhood, in which children’s and youth literature was one of the most powerful and effective devices.” In relation to his intense production, I present some book covers of Fanciulli:

Source: Reproduced by the author of this study from the collection of the Centro de Documentazione e Storia dello Libro Scolastico e della Letteratura per l´Infanzia, UniMC.

Figure 3 Some covers of books published by Fanciulli in the fascist period

To cite an example, Fanciulli in Glorie d´Italia (1929) writes a book dedicated to youth in which he tells the history of Italy, with several moments of building up patriotism. A brief presentation is written by Piero Parini, a fervent Fascist, who at the time of publication of this book was the Secretário dos Fascios all Estero, after that, assumes the Direzione Generale degli Italiani all'Estero. For Parini, Fanciulli’s book “tells the millennial history and exalts the men who rose to honor with their famous companies, their weapons, science, adventurous courage, fine arts, and the indomitable religious faith” and concludes in affirming that “Italy will live eternally and will yet be dominant” (PARINI, in FANCIULLI, 1929, s/p). Glorie d´Italia was illustrated with wood block printing by Marini Melis10.

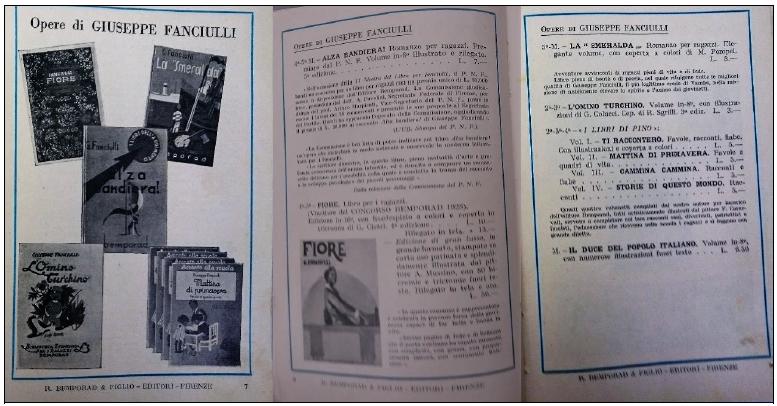

The second cover, from the book I nostri ragazzi was published in 1937 and develops a set of considerations and guidelines in relation to childhood development, the importance of care and the educational process. The third cover emblazons the book Fedeltà, a novel for boys, which was illustrated by Roberto Lemmi11. However, the works of Fanciulli were extensive. In a catalog of 1935 of the Bemporad Publishing Company, Edizioni per la Gioventù, the works of Fanciulli from this publisher occupy 3 pages, as shown in the figure that follows:

Source: reproduced by the author of this study from BEMPORAD, 1935, p. 6, 7, and 8.

Figure 4 Pages of the catalog of the Bemporad Publishing Company with works of Fanciulli, 1935

In his intense and extensive production, Fanciulli used pseudonyms such as Chichibio, but was known as Maestro Sapone. He published and had various books of history, reading, and tests for high schools, as well as the books that are analyzed here for religious teaching, approved by the book evaluation commissions for Italian schools in Italy and abroad. Fanciulli was married to Marialù Cadeddu and died on August 16, 1951, at 70 years of age, in Castelveccania, the province of Varese.

3 - Letture di Religione: production and circulation

Royal Decree no. 737 of March 11, 1923, established the guidelines for adoption of textbooks in elementary and popular schools, both public and private in Italy. The General Director of Elementary Instruction, Giuseppe Lombardo Radice, and teachers, ministerial employees, and men “of culture” composed the selection commissions that in June 1923 presented the first lists of approved books (ASCENZI and SANI, 2005). For the 1924-25 school year, the titles Gente Nostra, Creature, and Como sono Felice of Giuseppe Fanciulli were recommended for school libraries and also for distribution to students of Italian schools as prizes. Besides these books, the two volumes of Letture di Religione, written and compiled by Giuseppe Fanciulli, were approved. However, it should be noted that the editions analyzed in this study are of 1932 and 1935, and their covers are shown in Figure 5.

Source: personal collection of the author of this study.

Figure 5 Covers of the books Letture di Religione

The covers are the same. The two works of Letture di Religione had full pages illustrated by Beryl Tumiati12. The inside covers are likewise the same, changing only the identification of the volumes and the grades to which they were directed, as can be seen in Figure 6.

Source: Personal collection of the author of this study.

Figure 6 Inside cover of the books Letture di Religione

Note that the depiction on the inside cover of both books represents the helmets used by Roman centurions. The recurring argument is that the fascist “new Italy” is the resumption of the great Roman Empire, of which all Italians are heirs.

Of the books analyzed, the first, directed to the 2nd and 3rd grade, belonged to Nicolino Murino, a student of the Instituto Manzoni of São Paulo, as shown in Figure 7. There is no signature in the second volume directed to the 4th and 5th grade.

Source: Personal collection of the author of this study.

Figure 7 Inner signature - Letture di Religione

Analysis of the material aspects of the books shows a significant change in regard to the paper, the illustrations, and the use of colors of Italian textbooks produced in the 1920s and 1930s compared to the books sent by the government to the Italian schools at the end of the nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century. Superior quality paper, use of colors, and beautiful illustrations (more frequently present and in bold graphics for the time), a result of high investment, can be seen in the books. As stated by Galfré (2005, p. 27) “[...] the purpose of the government - according to official communication - is to give the book not only Fascist raiment, but also the Fascist soul”. The books bore an educational proposal linked to the fascist ideology that did not fail to consider and construct the relationship between country (fascist), moral conduct, religion, and family.

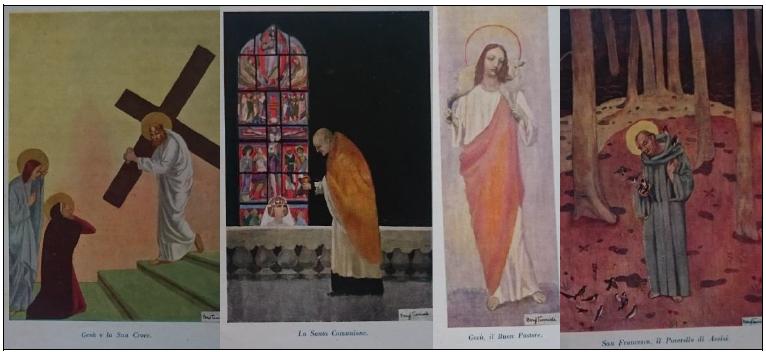

Volume I of the book Letture di Religione has 111 pages. Of these, 40 are directed to the second grade and 52 pages to the third grade. The second grade part works with themes related to creation of the world, the Ten Commandments, the sacraments, prayers such as the Our Father, Hail Mary, Glory Be, and Creed, some poems, parables told from the Bible, and simple questions along with responses. Illustrations occupy full pages and are more frequent. Short poems and songs are present. In a similar fashion, the part directed to the third grade begins by explaining who God is, who the angels are, moments from Jesus’ life, his childhood, youth, and adult age, highlighting the miracles, his attention to children, and his death and resurrection. Among the diverse illustrations by Beryl Tumiati, many of a full page in color, are the ones represented in the figure that follows.

The themes are taken up in brief texts, with short, direct sentences. There are short poems and questions followed by answers, like that exhibited in the Catechismo della Dotrina Cristiana. As shown already in the beginning pages of both volumes written by Fanciulli, “the questions and answers in bold and cursive print at the end of some chapters are given in the Catechismo della Dottrina Cristiana, published by order of His Holiness Pope Pius X” (FANCIULLI, 1932, p. 8).

Volume II of the book Letture di Religione has 159 pages, 42 of which are directed to the fourth grade and 98 to the fifth grade. In this volume, the amount of text is greater, and even the size of the font used is reduced. Another difference from the previous volume is that now small passages from Italian authors are inserted. For example, from page 17 to 18, we have the poem “God sees and knows all”, from the Italian historian Cesare Cantù. Other Italians such as Alessandro Manzoni, Contardo Ferrini, Saint Augustine, and Dante Alighieri have small passages or poems transcribed.

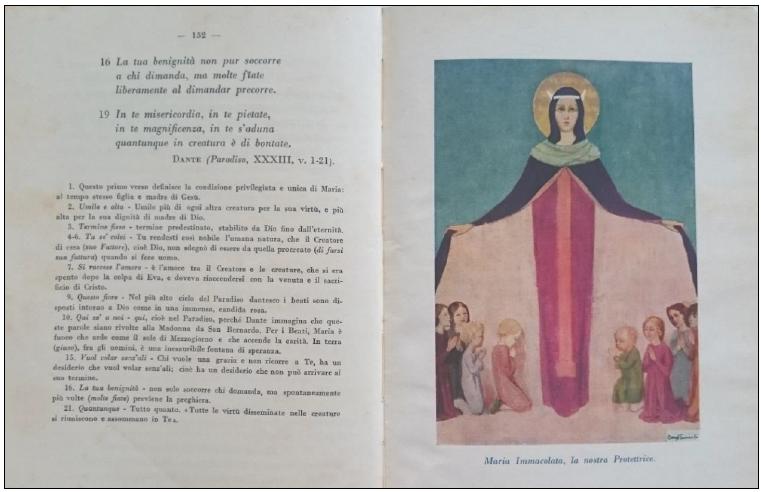

In regard to content, in the fourth grade are the morning and evening prayers, the Ten Commandments, Bible stories, and texts for First Communion. The fifth grade begins with the study of the liturgy and Mass rituals. After that, the sacraments of Baptism, the Eucharist, Confirmation, Matrimony, and Extreme Unction are highlighted. Finally, biographies of the “great Italian saints” are presented, including Saint Benedict, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Catharine of Siena, Saint Clara, and many others, such as Saint Aloysius Gonzaga (the patron saint of young students), Dom Bosco, and Saint Charles Borromeo. To finish his book, Fanciulli presents “A Madonna” - Immaculate Mary. The text begins by presenting the miracle, also referring to Italy, of “Nostra Signora di Gonare” of Sardinia, who saved the crew and the prince from a storm. Fanciulli wrote “Mary helped the sailors, and all of us are sailors on the sea of life; both coming and going on this journey, we find pleasant days of abundance and others of great torment and difficulty” (1934, p. 149). He urged all to plead and to thank, in good times and bad, so as to rely on the intercession of Mary. A small passage from the Divine Comedy, along with the interpretation of Fanciulli, and of the illustration shown in the following figure conclude this part.

Source: personal collection of the author of this study.

Figure 9 Image of Immaculate Mary - The Madonna

Thus, Letture di Religione presents pages filled with religious orientation, stories, and other texts that highlight respect for authority, the central role of work, and preservation of the family and of traditions. Lessons on morality and on which actions were desirable often appear: “Many men are good: they pray to God, love justice, perform charity, and prepare themselves to one day receive their eternal reward” (FANCIULLI, 1932, p. 54). This award “is called Paradise and punishment is Hell” (FANCIULLI, 1932, p. 30). Thus, children and youth were instructed to assume a posture of faith, professing moral values, praying, and “avoiding all temptations” (idem, p. 104).

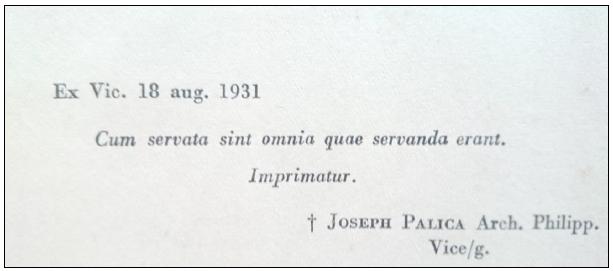

It is noteworthy that both volumes contain the “imprimatur”, granted in August 1931 by Archbishop Joseph Palica13 (1869 - 1936). “Cum servata sint omnia quae servanda erant” (FANCIULLI, 1932, p. 111), i.e., observing all things that should be observed. Record of this was maintained in production of the book and is shown in Figure 10.

Source: personal collection of the author of this study.

Figure 10 License for printing the books Letture di Religione

The publication of Giuseppe Fanciulli, Letture di Religione, was doubled approved - by the Fascist State and by the Catholic Church - to be sent to Italian schools abroad. Finally, it is noteworthy that the books were printed in the A. Mondadori printing company in Verona, just as so many other works published by the Fascist Italian State (see more in Galfré, 2005). Charnitzky (1996) states that a general feature of the texts was “continuous politicization of the themes, through interweaving of religious and political content, culminating in the representation of Mussolini, also disseminated in numerous non-scholastic publications, as sent by God to save Italy” (CHARNITZKY, 1996, p. 406). In the case of Fanciulli’s books analyzed here, manners of being and acting are propagated not only by biblical passages and prayers, but also by a selection of texts from names important for the history of Italy who wrote about this connection between country and Catholicism. The stories of the lives of the saints presented are also not at all at random, but exemplary. They are connected with this nationalist perspective of constitution of the “new” Italian, respecting hierarchies and cultivating values and responsibilities.

Final considerations

“Paradise is the award of the Christian life” (Fanciulli, 1935, p. 153) and “as the most beautiful award”, it may only be obtained by those who are faithful, devoted to the good of their family and their neighbor, “ready to serve their country with all their might”, enthused by the beauty of nature and of art, and obedient to their duties. They are able to resist temptations and follow instituted norms. A Christian who lived out “these rules would be the best child, the best brother, the best soldier, the best citizen” (Fanciulli, 1935, p. 154). This was what was expected of an Italian abroad - with a dual devotion to Catholicism and to fascism. However, appropriation of the content of books may have been diverse, as Chartier alerts in affirming that “[...] each reader, based on his/her own references, individual and social, historical or existential, provides a more or less unique sense, that is more or less shared, to the texts that are appropriated” (CHARTIER, 2009, p. 20).

The works analyzed were distributed in Brazil by consulates and consular agents. They were used in the ethnic schools for a short interval of time, since most of these schools were closed in 1938. Nevertheless, that does not mean they were put aside. Through the themes they worked with, they remained in families and were read by children and youth under the guidance of parents, and even some priests. The complexity of the dynamics and historical processes experienced at that time between Italy and Brazil cannot be fully explored in one article. Yet, the books examined allow recognition that they are part of a literate childhood culture that seeks to (con)form identity processes of “Italians abroad”, ordaining a view of the world, a place in the social fabric, and manners of behavior and of being and becoming in the world.

Furthermore, the author of the works, as Montino (2009) indicates, produces his own reading of that historical time in the relation between faith and nationalism. Montino wrote of “Fanciulli’s faith, a faith that is not conventional but a profound choice of life, since one cannot diminish the spirituality of a good man”, because living at that historical time, Fanciulli interpreted “a certain type of Catholicism [...] that was national and also nationalist [...] that does not fear war as an instrument of patriotic affirmation and of transmission of civility” (MONTINO, 2009, p. 212).

Understanding the knowledge produced and disseminated by the use of didactic material linked to the fascist ideal and to the Italian governmental policies directed to supplying specific materials to Italian schools abroad, together with the question of the uses and symbolic sense that these objects acquired in the sphere of the school, is a relevant theme for the History of Education. The presence of teachers sent by the Italian government, the sending of school material, especially textbooks, and the propagation of fascist speech in the environment of ethnic schools was a reality. Nevertheless, ensuing reactions were not exclusively of the Brazilian government from measures of nationalization of education in the 1930s. In the Italian-Brazilian communities themselves, compatibility with Il Duce and the fascist regime was not uniform.

The aim of this article was to contribute to understanding the multiplicity of Brazilian schooling processes, considering their ethnic and cultural diversity through analysis of two religious teaching manuals produced and sent by the Italian government to Italian ethnic schools in Brazil.

texto en

texto en