The legal and social-cultural context behind the establishment of nurseries in Portugal2

For obvious reasons, nurseries are situated in industrial and urban centres, and normally take in children from their very early months of life, but only during the day. Although on exceptional occasions they could cater for cases of widowhood or sickness, their purpose was not to shelter orphans or the unprotected (abandoned children). These structures were established within the legal constitutional framework of 17th century associativism, because they had to be formally constituted as associations governed by the usual statutory requirements for the existing common associations at the end of the century. They were set up and survived thanks to philanthropy contributions until democracy was consolidated in the 1980s. At first, the sums needed to cover the expenses of a nursery (capital, furniture, utensils, food, etc.) came from one-off charity donations of varying amounts, most of which by the Masonry (cf. BAPTISTA, 2018).

In Portugal, the first educational facilities specifically designed for children were the “Casas de Asilo da Infância Desvalida” [Shelters for Underprivileged Children] established in 1834 with the purpose of protecting, educating and instructing poor children, from the time they were weaned to the age of seven, and for girls up to nine years of age, to allow their parents to work. The need for this type of institutions explains why they spread so quickly, providing care to about 1,520 children at the dawn of the Republic3.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, as shelters and nurseries spread, discussions on child education based on the models advocated by Pestalozzi and Fröebel4 began to take shape, especially in Lisbon and Porto, as a result of the movement raised by the “Sociedade de Instrução do Porto” [Porto Education Society]. The Legal Charter of 2 May 1878, by António Rodrigues Sampaio, and the Legal Charter of 11 June 1880 endorsed by Luciano de Castro5 were proof that interests were pedagogical more than social, invoking the need to educate children prior to the compulsory school admission age and, thus, calling for the establishment of education facilities and nursery schools and for the help of private entities to help set them up6. Nonetheless, only the Fröebel nursery, founded in 1882 at Jardim da Estrela in Lisbon - a purpose-built facility that put into effect modern pedagogies - was an exception in this paradoxal scenario between confessed pedagogy and the law in force and the actual socio-educational reality.

Two other 19th century highlights are worth noting: José Augusto Coelho’s nursery school7 in Porto8 and the development of some relevant legislation, one example being the Regulatory Degree of 22 December 1894, approved on 18 June 1896, on the objectives of pre-school education and teacher training. Finally, in 1896, Government Gazette no. 141, of 27 June, laid out the objectives, conditions and operating standards for nurseries, recognising the need to train teachers for these institutions (MARTINS, 2006, p. 106).

Even before the first law on nurseries was enacted in Portugal (Decree of 14 April 1891), several nurseries were established in the “Porto” urban area: Bom Pastor (1877), Aula Infantil do Torne (1883), Santa Marinha (1888) nurseries, followed by the Cedofeita (1891) and Afurada (1893) nurseries.

In 1906, a nursery was set up at Colégio da Boavista, run by a German nursery teacher that used Fröebel’s methods9. In fact, until the early 20th century nursery institutions implemented the Fröbelian teaching method. Law 233 of 7 July 1914 provided for the establishment of Normal Schools in Lisbon, Porto and Coimbra that replaced the Normal Education Schools and the Teacher Training Colleges. It also determined that students in their two last years would have to apply the knowledge acquired into primary or nursery education at the Schools Attached to the Normal Schools, meaning that each Normal School would have an education facility for children between the ages of four and eight, where, according to FERREIRA; MOTA; VILHENA, Fröebel’s education model would be implemented (2019, p. 17).

With the Republic in place, the new political leaders made efforts towards the “Republicanisation” of society, attaching priority to education and, within it, to children’s education (from the age of 4). The Decree of the Ministry of the Interior issued by the Geral Directorate for Primary Education (29 March 1911) and the Decree of 23 August reformulated the primary and normal education of children and encouraged the transformation of shelter-type institutions (which covered the nurseries10) into kindergartens; however, we have still to determine which establishments implemented the suggested changes and in what ways.

The first João de Deus nursery was inaugurated in Coimbra in 1911, a project of the “Associação das Escolas Móveis João de Deus” [João de Deus Mobile Schools Associations] for children between the ages of three to seven, which was followed by other nurseries in the First Republic.

The 1919 reform, which adopted the previous legislation and regulated Leonardo Coimbra’s decree (Decree-law 5787-A, of 10 May 1919)11, suggested the use of the Fröbelian materials and the Montessori method, reiterating the need for nurseries in all district capitals and municipalities (Cf. GOMES, 1977, p 76).

In the late 1920s, the Montessori method disseminated by Luísa Sérgio and António Sérgio competed with Fröebel’s method, more in keeping with modern psychology and scientific pedagogy, and more attractive for the New School movement (FERREIRA; MOTA; VILHENA, 2019, p. 18).

In 1923, João Camoesas presented a Draft Law (22 July) on the reorganisation of National Education, elaborating on a number of aspects on children’s education and proposing the establishment of “nurseries” at the faculties of Education Sciences, but this only materialised more than 60 years later.

During the early Military Dictatorship period, given the “reluctance shown by the industry, families, minors, and women, and the difficulty in regulating and implementing the essential protective measures” (Official Journal 240/1927), decrees 14.498 and 14.535, of 29 and 31 October 1927, respectively, attempted to “revive” the 1891 decree, stating that all industries employing more than 50 women had to provide a place where children up to the age of 1 could stay, in addition to breast-feeding facilities for all other companies.

Generally speaking, the first few years after the 28 May military coup did not lead to significant shifts in children’s education: “acknowledging its benefits, a slight increase in the number of laws, and very few actual achievements” (GOMES, 1977, p. 90). We note, in this period, the role of Irene Lisboa12 and Ilda Moreira13 in setting up the children’s education divisions at the Tapada da Ajuda Schools, in Lisbon. Irene even proposed a pioneering children’s education programme strongly influenced by the New School movement (BAIRRÃO; VASCONCELOS, 1997: 10; FERREIRA; MOTA; VILHENA, 2019, p.21).

The doctor and teacher Bissaya Barreto took the slogan “Let us make our children happy” to carry out a plan initiated in 1936 to offer expecting mothers, low income mothers and children better living conditions, and supported a wide range of children’s welfare and educational initiatives in central Portugal.

When Carneiro Pacheco joined the government (1936), he entrusted the supervision of childhood education to “Obra das Mães para a Educação Nacional” [an association of Mothers for National Education, mainly drawn from the female elite of the Estado Novo regime], responsible for promoting and ensuring pre-school education across the country to complement the role of the family in this field. Following this, the enactment of Decree-law no. 28.081, of 9 October 1937, extinguished nursery education. The argument found for justifying such a measure - the lack of resources for expanding the network and the equal treatment of citizens - was clearly deceptive. The Estado Novo regime advocated that education lay in the hands of the families, and not of the State, opposed coeducation of children, and there was even a time when educational institutions for pre-school aged children were regarded as influential on the breakdown of families. If to this we add the fact that some thinkers and educationalists were accused of subverting customs and mores, we realise that the fight against children’s education was fertile ground for ushering in the authoritarian discourse for the grassroots classes and for channelling it to the anti-Communist campaign supported by some intellectuals who extolled the virtues of the poorly educated Portuguese people (FELGUEIRAS, 2012: 36-7).

The Estado Novo regime washed its hands of childhood education, handing it to the families and transferring it to the realm of the home, the right place for developing “feeling and character” linked to lifelong learning founded on education for work, and for transmitting ways and customs. In view of these objectives, school was “like a barrack, depersonalised. Family conditions are far better than those of schools when educating children up to the age of seven. But will families fulfill their educational role?”. This is where the role of the State was brought into the equation: to educate families and improve the education of the people14. Building nurseries, milk dispensaries, and kindergartens was simply not enough: “we need to go further back along the line, back to the families”15. The intervention of nurseries and kindergartens and women’s work outside the home had to be reduced to a minimum: “The best way to defend children is to protect the family, having the mother stay at home, that is, so that she does not have to go out to work”16.

While in the late 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century it was argued that childhood education should be universal, regardless of social class, based on a new approach to childhood that called for the need of a certain “professionalisation of motherhood” and for women to be taught to scientifically educate children (FERREIRA; MOTA; VILHENA, 2019, p. 9-11), from the Estado Novo period onwards the idea of a domestic motherhood, unplanned, went hand in hand with “a considerable step backwards in the history of childhood education, when it was considered that its mission was mostly of an assistance type, and its educational role was underestimated”(CARDONA, 1997, p. 50). During the Estado Novo period, childhood education gradually became restricted to private institutions, without clearly defined educational objectives and no specific qualifications required.

Source: Mocidade Poeruguesa Feminina: Bolteim Mensal, 1942, n. 33: 1.

Fig. 1 Front page of the magazine Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina [Women’s national Organisation]: Boletim Mensal, with the following caption: “The new crib occupant: crib offered by M.P.F. to a mother of eleven children”.

The Social Relief Fund, established by Decree 35.427, of 5 April 1945, “solved” the State’s and industries’ problem of working mothers: companies no longer had to set up nurseries if they paid 6$/month [Escudos - the currency used in Portugal at the time] for each woman employed. As a result thereof, in strongly industrialised municipalities, for example, in Vila Nova de Gaia, in 1969 only 385 children were “protected and received education at nurseries and kindergartens»17 in a universe of 25,974 children up to the age of six, whose parents received welfare protection, and in 1971, in Guimarães, there was not one nursery working near manufacturing companies (AR-DP - Diário […], n.º 98, 1971).

The adherence to the “Regional Mediterranean Project” represented the start of a turning point that reached its peak, during Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano’s office, with the Reform by Veiga Simão (Law 5/73, of 14 July), but which otherwise have the same objectives for pre-school education as those proposed by the Republican government.

The influx of women into the labour market was gradually widespread across all social classes. At the same time, in the 1960s, migration to the cities increased, as did longevity, causing the number of children to decrease in relation to the overall population. As such, their survival and education deserved increased attention, as the education of small children became more valued, also on account of the development of psychology and sociology. On the other hand, as living conditions generally improved, expectations about the future of children increased, with the school becoming more relevant as a means of social promotion. Moreover, the high rate of pupil failure also contributed to enhancing the role of childhood education in children’s early training years (CARDONA, 1997, p. 58). Although Portugal had a lot to catch up with other European countries, it nevertheless felt the social changes resulting from the growing industrialisation: the migration of families from the villages to the large cities at the turn of the 1960s; the number of children enrolled in primary education increased, as did the number of salaried women employees, boosted by the need for women to enter the labour market due to the beginning of the Colonial War (CARDONA, 1997, p. 59).

In 1974, and in compliance with the 4th Development Plan, more than fifty nurseries (kindergartens) were expected to be refurbished and 25 others were supposed to be established (AR-DP - Diário […], n.º 34, 1974). Following the post-25th April frenzy for Democracy, work began to carry out a large number of initiatives supported by the municipalities and the State, draft an extensive number of legal documents on the pre-school sector, with a view to their integration in the official system and, at the same time, define the general outlines of the plan for the development of the public institutional network (MARTINS, 2006: 103).

Childhood education is established as a public service by Law 5/77, which limited pre-school education to children between the ages of three to five, with nurseries remaining under the supervision of the now called Ministry of Solidarity and Social Security (IPSS - Private Institutions of Social Solidarity).

The Education System Act - Law 46/86, of 14 October -, includes, for the first time, the education of children from three to six years of age under the definition of Basic Education. Despite the ecological approach to the entire educational process18, “nurseries” (for children up to the age of three) were nevertheless left out of the national educational system, a decision reiterated in the 1998 revision, it not being acknowledged that education begins from birth (apud CARVALHO, 2014, p. 20). The OECD report on the thematic study “Early Childhood Education and Care in Portugal” (2000) justified this decision on financial grounds and “a concern about transferring such a costly sector to the Ministry of Education” (apud TADEU, 2014, p. 167).

Pre-schools thus remained under dual control: public kindergartens under the Ministry of Education, and the IPSSs, which include nurseries, under the control of the Ministry of Solidarity and Social Security. “This dual pedagogical and administrative dependency illustrates the uncertainty over the objectives and functions of childhood education” (DIAS; CORREIA; PEREIRA, 2013, p. 667).

Nevertheless, despite the fact that the legislation only included pre-school education from age 3 and up, thus not including nursery education, in accordance with the Recommendation of the National Board of Education it is considered that the latter is a child’s right and, therefore, consistency is required across childhood education and professional work with children before they enter compulsory schooling should be based on common grounds. The current Curriculum Guidelines for Pre-School Education (2016) stresses this uncertainty over nurseries again, quite clear in the ambiguity between legislation/pedagogical practice and qualification requirements/professional downgrading, the clarification of which has been postponed.

The Gaia urban landscape at the turn of the 120th century

Vila Nova de Gaia is a vast territory marked by a contrasting landscape and socio-economic background. At the turn of the 19th century, the commercial and industrial bustle in the vicinity of the Douro river mouth and the railways contrasted with the rurality and conservatism in the greater part of the territory. The parishes of Santa Marinha and Mafamude19 were undergoing a process of transition from a peasant society to a society in the process of industrialisation and urbanisation, and undergoing social reforms. Development herein served to attract national and international investors and members of large rural families from the immediate surroundings and the countryside.

The displaced proletariat lived in the so-called "casas de malta" [which one could call slum houses]20, a sort of cheap dormitory-style bedrooms for housing workers in the city during the week. Unhealthy conditions and concentration of population helped spread tuberculosis, smallpox and measles, also contributing to the onset of other diseases. The modern railway bridges of D. Maria Pia and D. Luís had become the favourite spot for the poor to expose their misery and diseases (AR-DP - Diário […], n.º 120, 1914: 30). The local press also criticised the unhealthy conditions, poverty and social degradation21, and in 1897 one newspaper even went so far as to appeal to the intellectuals and capitalists in the region about the possibility of annexing Gaia to Porto due to the various problems22 that this young municipality faced.

Vila Nova de Gaia was one of the most populated municipalities in the country. However, the increase in the infant mortality rate in the early 20th century (1906) raised suspicion of criminal activity, forcing the deputy health officer of this municipality to call all its doctors to investigate the causes and find solutions to fight this scourge of diseases. At this meeting, the idea of criminal acts being the cause of increased infant mortality was not accepted, but they instead noted the neglect, ignorance and poverty of mothers as the major cause thereof. It was, therefore, particularly important to educate mothers about feeding habits in early childhood and, because these mothers were illiterate, these instructions would have to be passed on through the parish priests (O Portucalense, 1906).

The explanation given for the high mortality rate in early childhood was the “industry” of child carers that had developed unmonitored. Indeed, hundreds of employed women from Gaia (tobacco handlers, milk, fruit, bread and fish sellers, etc.) worked in Porto every day, while others worked in the municipality as bottlers, bottle-sealers, spinners, pottery makers, etc., so they had to rely on the child carers, that is, women who looked after the children of these working mothers until they returned home from the factories. Our conclusion is that although there were some good child carers, the development of the profession had turned it into a real industry, on in which the child’s health succumbed to greed. It was suspected that this profession was the cause of the death of many children, who died due to food unfit for consumption given to them out of ignorance or even through criminal intention. Requests were made for the monitoring of the activity, autopsies, milk inspections, and for encouraging best practices by awarding prizes to compliant child carers. Another request made concerned the protection of pregnant women, as was already being done in Porto. In other words, through employer philanthropy and working-class mutualist associations, even giving some examples to attract the industrialists of Gaia to this type of charity, in particular Fábrica José Mariani and Fábrica de Moagem de J. Andressen (O Portucalense, 1906, n.º 33, p. 1).

The political-social23 and academic milieus were a hive of activity: speeches, conferences and theses published to minimise the problems raised by the industrialisation process. Among the various doctors’ opinions, Ferreira de Castro was one to state that much more was needed than just informing the population through parish priests. In order to fight against infant mortality, pregnant women workers had to be provided with cash benefits and maternity leave in the last month of pregnancy and the first four weeks after giving birth, and to have their workplace secured. Children also had to be protected through child protection services (one in each parish), intended to educate mothers, child carers and nannies in charge of watching over the children and to monitor the milk available in the municipality. Ferreira de Castro also advocated the need for setting up institutions in support of the proletariat, in particular milk dispensaries, dispensaries and nurseries. However, “there were only two establishments regularly set up in the whole municipality for a population of close to 3,000 children under 1year of age”(O Portucalense, 1906, n.º 33, p. 1).

These issues related with the child’s specificity and protection were, indeed, visible in the social, professional and political contexts of Vila Nova de Gaia. At the turn of the 20th century, we note Ângelo Vaz, son-in-law of Bernardino Machado, who was twice elected as President of the Portuguese Republic, both masons. Born in Lisbon, Ângelo Vaz attended the Fröebel school in Jardim da Estrela, and then the primary school Escola Municipal n.º 11 in Lisbon, and later graduated in Medicine with a specialisation in Paediatrics (ABREU, 2013, p. 1418-9). He opened his practice in Porto, where he cared for children and educated mothers on hygiene and eating habits. One of the news published at the time reported that one of his intentions was to open a “School for Mothers”, in addition to organising children’s holiday camps (A Defesa, 1906, n.º 51, p. 3). In his doctoral thesis submitted to the medical-Surgical School of Porto, entitled Neo-Malthusianism, he examines controversial issues related with “free love” and planned pregnancy, confident that “a good birth, good education and proper social organisation prepares the arrival of a new time of happiness”, and that human pregnancy was a moral and social responsibility (VAZ, 1902, p. 112, 115).

Neo-Malthusians dreamt about and aspired to form a new mankind, vigorous and powerful in its physical and mental life, thanks to a conscientiously desired and freely accepted selection (VAZ, 1902, p. 107). […]

First, let the full spread of sexual desire and the free union of the sexes become a reality, unfettered by all things that repress and distort them in today’s society. Then, when the woman, forever freed from the oppression and domination of man, is able to conscientiously and freely choose a life partner, free motherhood will be the logical consequence of free love. The woman will have the legitimate right to decide when she wants to be a mother.

Free love and free motherhood can not be dissociated from a broader concept of family. Once a sexual union occurs, entirely free from all conventional practices that dominate and enslave the current institution of the family, man and woman will both agree to give life to stronger and more perfect offspring (VAZ, 1902, p. 111).

Ângelo Vaz published articles in several newspapers, for instance, As mães. Conselhos para uma boa higiene e alimentação das crianças [Mothers. Advice for good hygiene and eating habits for children]. He also established professional and political relationships with personalities of Gaia, and was the appointed doctor at “A Infantil. Associação de Proteção às Crianças (Socorro Mútuo)” [Association for the Protection of Children (Mutual Aid) (A Defesa, 1906, n.º 51, p. 3) and, later, he became a teacher and school doctor at the Higher School of Gaia. The above association was founded in 1905 to cover a broad area that included the two districts of Porto and the parishes of Santa Marinha, Mafamude and Oliveira do Douro. Its main purposes was to provide aid to the children of its members up to the age of fourteen - medical assistance, medication and bathing in the sea, and helping those members unable to work and arrange for the funeral of the member and his household (ADP, Estatutos de A Infantil. Associação de Socorros Mútuos, 1909).

Besides being a politician and teacher, António de Almeida Garret was also quite influential in hygiene and paediatric matters. As the President of the General Board of the Porto District, he gave a public speech at the head-office of the Association of Nurseries of Santa Marinha, praising the prophylactic and educational role of this type of associations for the poor population (ADCSM - Livro de Actas […] [1929-1936]: 70v).

During the Estado Novo period, it is important to highlight the role played by the physician Leonardo Coimbra24, a resident in Vila Nova de Gaia where he managed the D. Manuel II Sanatorium (1950-1955) and founded the “Associação Protetora da Criança contra a Crueldade e o Abandono” [Child Care Association against Cruelty and Abandonment], in 1953, which was completed in 1960 with the inauguration of a Children’s Recovery Centre. The purpose of this institution was to provide the medical, social and psycho-pedagogical conditions for children socially excluded due to misbehaviours, but able to be re-educated, or intellectual deficits. This institution is, today, an IPSS, presided over by one of the founder’s sons. He also founded the magazine A criança [Children] (1954-5), with head-office in this municipality, which aimed at the protection of children’s interests, among other objectives.

Nurseries in Vila Nova de Gaia

The first nurseries in Portugal were established in Vila Nova de Gaia, Porto, Lisbon and Coimbra. This pioneering endeavour was justified, on the one hand, by the growing trade and industries, followed by the increase in population and, on the other hand, by the political-social and academic environment that fostered and advocated the dissemination of protection/popular education facilities like nurseries.

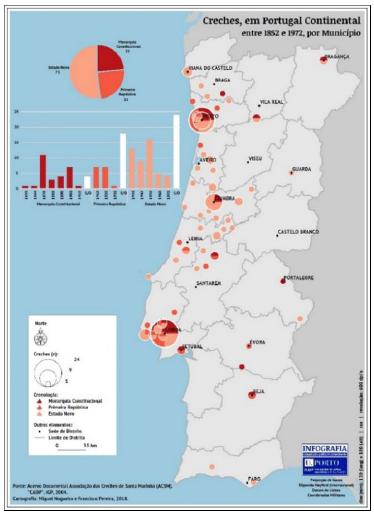

Source: Arquivo Documental da Associação das Creches de Santa Marinha; Cartografia de Miguel Nogueira e Francisco Pereira, 2018.

Map I Nurseries in Mainland Portugal between 1852 and 1972, by municipality.

Table I Nurseries in Vila Nova de Gaia (1883-1972)

| QUADRO 1 - AS CRECHES EM VILA NOVA DE GAIA (1883-1972) | |

|---|---|

| Data de criação | Designação |

| 1883 | Aula Infantil do Torne |

| 1888 | Creche de Santa Marinha |

| 1893 | Creche do Colégio Nossa Senhora do Rosário (Convento Corpus Christi) / Colégio-Creche Nossa Senhora do Bonança |

| 1893 | Creche da Afurada - filial da Creche de Santa Marinha |

| 1894/1915 | Creche da Fábrica Cerâmica das Devesas |

| 1942 | Creche da Coats & Clark |

| 1944-1950 | Creche de Arcozelo |

| 1949 | Creche da Real Vinícola |

| 1956 | Creche da Sociedade dos Vinhos do Porto Constantino, Lda |

| 1971 | Creche da COTESI - C.ª de Têxteis Sintéticos SARL, Grijó |

Source: Baptista, 2018.

Protestant welfarism was the first to carry out the first pre-school level experience in the region under study. Back in 1883, Diogo Cassels already provided a “Children’s class”, fully operational from 1894 on. This class was intended for children under the age of seven, teaching the basics of reading and whose purpose was to “entertain children an take them off the streets”25.

Several founding individuals of different ideologies and creeds came together when the Santa Marinha Nursery was established in 1888: bourgeois and republicans, members of the conservative aristocracy, for example, the Count of Campo Belo - who even sponsored a nursery that once existed in the Convent of Corpus Christi in the 1890s, run by the Sisterhood of Nossa Senhora do Rosário and S. Domingos de Gusmão26, integrated in the school Colégio Nossa Senhora do Rosário and under the educational supervision of the Hospitaller Sisters of the Poor for the Love of God. Several problems created by the exacerbated anti-clericalism of the Republic forced this institution to be transferred to rua do Castelo, where it took the name of School-nursery of Nossa Senhora do Bonança, as it was situated close to a chapel with this same name27. Santa Marinha Nursery first opened its doors at rua das Costeiras (today rua Dr. António Granjo), n.º 22, 2.º, which was owned by one of the founders, an advocate of republicanism and a mason, João Rodrigues Valente Perfeito. It was then transferred to a nursery that was part of the building that housed the Gaia Club, at largo D. Luís and Avenida de Diogo Leite, n.º 77-B. The institution finally settled in its final location in 1897, a palace facing the Douro River, where it remains to this day.

Source: Arquivo Documental da Associação das Creches de Santa Marinha.

Fig. 2 View of a room of the Santa Marinha Nursery in the 1980s.

The Santa Maria Association of Nurseries was established in 1893 with the annexation of the Afurada nursery, built atop Monte Cavaco. The origin of this nursery is related to the tragic shipwreck that caused the death of more than one hundred fishermen, thirty five of whom were from Afurada. The newspaper O Comércio do Porto took the initiative, together with the director of the Santa Marinha nursery, Mason Artur Ferreira de Macedo, to muster the forces needed for building a facility near this Gaia fishing community. Due to various events, he left his teaching functions in the 1950s (vd. BAPTISTA, 2018, p.30).

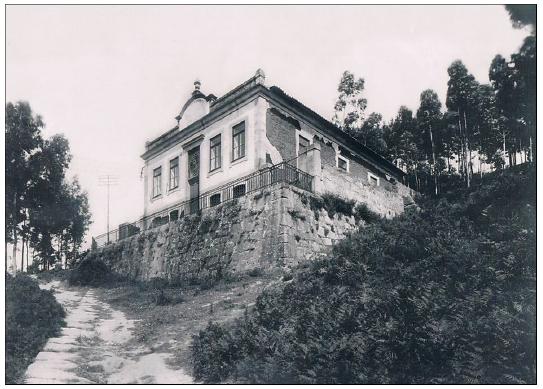

Source: Arquivo Documental da Associação das Creches de Santa Marinha.

Fig. 3 Afurada nursery (a branch of the Santa Marinha Association of Nurseries), in the 1930s.

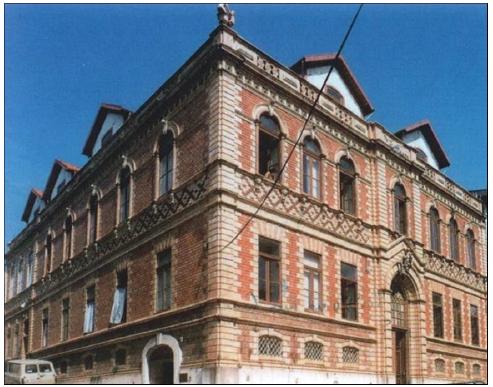

Source: Correia, 2014, p.184.

Fig. 4 The building of the first nursery owned by Emília and António Costa.

In 1894, a “Kindergarten” operated in the Social Centre of the Devesas Ceramic Factory28 funded by its owners. This facility would become the embryo of the “D. Emília de Jesus” nursery, built and inaugurated in 1915 in a building that also housed a retirement home, hence why the institution was renamed “Asilo Creche e Hospital Emília de Jesus Costa e António Almeida Costa” [Emília de Jesus Costa e António Almeida Costa Retirement Home-Nursery and Hospital]29 in memory of its founders. The nursery moved to its new premises in 2001.

Source: Photo credits: Abel Barros.

Fig. 5 View of the façade of the “Emília Jesus Costa Nursery and António Almeida da Costa Retirement Home”.

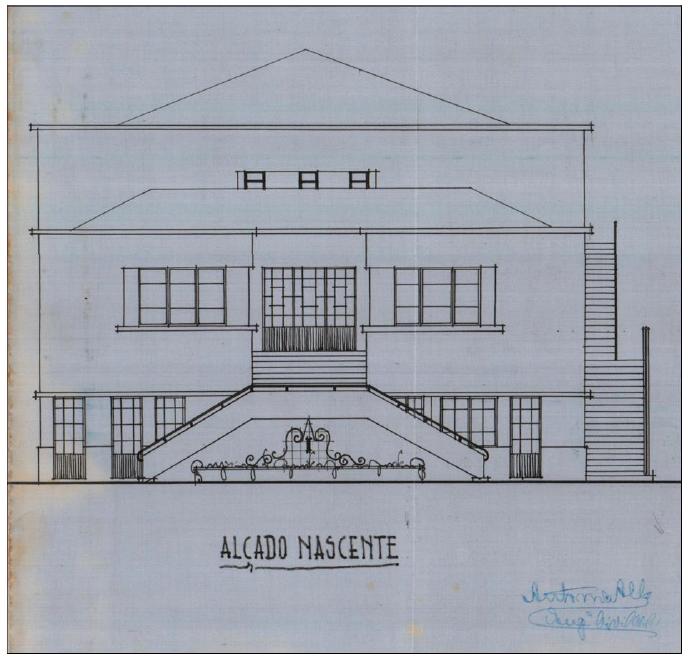

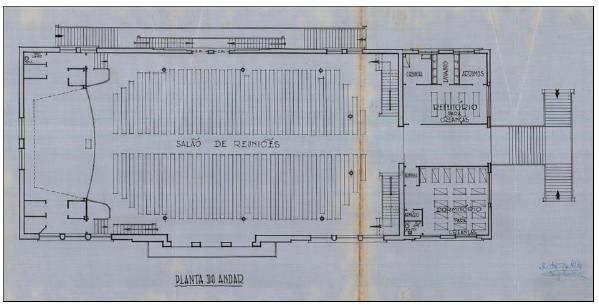

After this successful expansion of nurseries, it was only in 1940 that the Crestuma Weaving Factory decided to establish a nursery at its manufacturing site. The company was authorised to erect a building consisting of a canteen, showers, meeting rooms and a nursery planned for the 1st floor, on top of a facility for the storage and sale of fruit. Two flights of stairs gave access to the nursery area, which was divided by a 4 meter-wide corridor leading to the meeting room. It had a “small kitchen, a dining room for the children, one room for the carer, a room with wash basins for the children, a dormitory with 18 small beds, a linen closet and a toilet”, nd had 4 wide windows for natural lighting. However, an addition to the project dated back to 1942 shows that only the canteen and the showers were built (AMSMB/CMVNG - Private Construction Work Plan in the name of Crestuma Weaving Factory, 1940). As the required materials were very expensive and difficult to find, as a result of the instability caused by the 2nd World War, these works were postponed ad perpetuam (TEIXEIRA, 2017: 172).

Source: AMSMB/CMVNG. Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Companhia de Fiação de Crestuma, 1940.

Fig. 6a Vie of the façade of the building that housed the nursery premises of Companhia de Fiação de Crestuma (Detail).

Source: AMSMB/CMVNG. Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Companhia de Fiação de Crestuma, 1940.

Fig. 6b Detail of the 1st floor plan (meeting room and nursery).

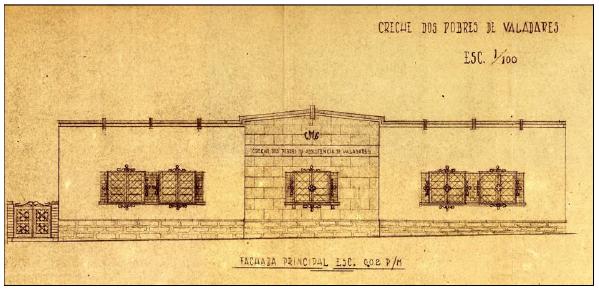

The nursery for the Poor of Valadares, which the Assistance for the Poor, in the same parish, had requested also never saw the light of day. This intention of this association was to build a “shelter-nursery” for factory and farm workers’ children, so that they could be “cared for properly by the ladies of the S. Vicente de Paulo Congregation”. They were concerned about the dignity of the local children and their very poor living conditions: “[…] children can sometimes be seen wandering about in the streets, some naked and others wearing tattered clothes, representing a danger and an eyesore for society” (AMSMB/CMVNG - Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Assistência de Valadares, 1948)

Source: AMSMB/CMVNG: Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Assistência de Valadares, 1948.

Fig. 7 Detail of the façade of the building project for the “Valadares Nursery for the Poor”.

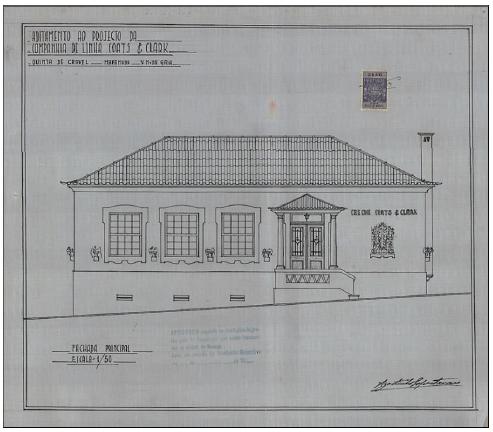

Coats & Clarks Thread Manufacturers successfully opened a nursery that provided medical assistance to the minor children of its workers in 1942, in the parish of Mafamude. Its construction was managed by Agostinho Lopes Tavares, master builder graduated at the Passos Manuel Industrial School, featured the best materials, ceramic mosaic and tiles on the floor and kitchen walls, with plans for a bathroom and a flush toilet linked to the main waste pipes of the factory (AMSMB/CMVNG - Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Companhia de Linhas Coats & Clark, 1942-3). As the factory closed in the late 20th century, the nursery was acquired by the City Council.

Source: AMSMB/CMVNG: Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Companhia de Linhas Coats & Clark, 1942-3.

Fig. 8 Detail of the façade of the Coats & Clark Nursery.

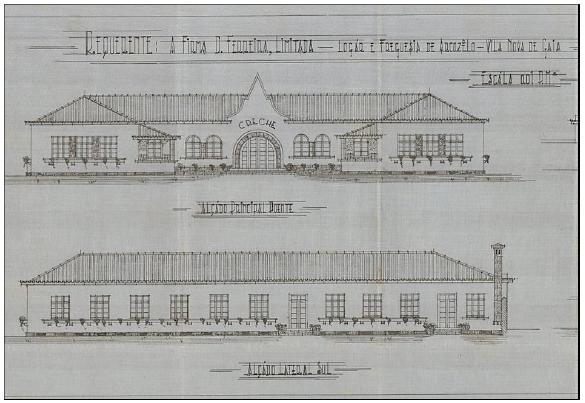

The cotton factory D. Ferreira, Ld.ª, in Arcozelo, set up a model milk dispensary-nursery for the children of its workers, as described in the “Project Description”. The industrial complex is now a commercial hub and the nursery is not working anymore.

The construction will be built on clean grounds and will consist of the required rooms for housing fifty children.

The materials used will be chosen so as to ensure the proper hygiene conditions.

The depth of the foundations will be as required and their base will be strong enough to withhold the loads to which they will be subject. The elevation walls, partly in 0.50 bonding-stone and partly in 0.28 bonding stone (as shown in the project), will develop from the second footing. They will be paved for insulation of the unit at the appropriate height. The walls will be built in rustic stonework, as well as the columns, supports, steps and the main entryway. The entire floor will be paved in concrete, properly insulated and tiled with mosaic or cork. The roof structure will consist of the necessary trusses, with 0.23x0.09 beams, 0.07x0.06 rafters and 0.04x0.022 battens. The ceilings will consist of wedge joists and lath. The doors and outer door frames will be in chestnut wood and the inner door frames in pine wood. All door panels and frames will be removable.

The roof will be cladded with “Mourisca” type tiles and gutters will be built in galvanised sheet. The outer walls will be coated with ceresin wax, then finished with cement mortar and plastered, in pink, and inner walls will be finished with cement mortar and plastered in white. The floors in the hall, kitchen, milk preparation room and washing room, linen closet, washroom, toilet, bathroom and chemist will be tiled with mosaic tiles, and the walls will be cladded with tiles up to a height of 1,50; the remaining floors will be cork. Wood elements will be painted with “Enamel paint”, brown on the outside and white on the inside. Glass panels will be in Portuguese glass. Water will be supplied by the wells found on the property. Sanitary works must comply with the provisions in the Building Regulations, approved by Decree of 14 February 1903 (AMSMB/CMVNG: Processo de Obras particulares em nome de D. Ferreira Ld.ª, 1944-1951).

Source: AMSMB/CMVNG: Processo de Obras particulares em nome de D. Ferreira Ld.ª, 1944-1951.

Fig. 9 Detail of the Arcozelo nursery façade.

As regards Port wine companies, we know that Real Vinícola opened a nursery at the end of the 1940s (AR-DP - Diário […], n.º 120, 1914: 30) and in 1956 Sociedade dos Vinhos do Porto Constantino, Lda., aiming to improve its facilities, presented a construction project for a pavilion to house a canteen and a kitchen, including “a small nursery (dormitory, dining room and toilets) for the workers’ children under the age of 6” (AMSMB/CMVNG - Processo de Obras particulares em nome da Sociedade dos Vinhos do Porto Lda., 1956).

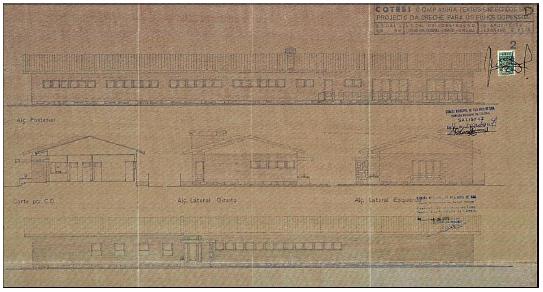

In the early 1970s, in the parish of Grijó, the company Cotesi - Companhia de Têxteis Sintéticos, S.A.R.L., founded a nursery for the workers’ children, planned for 100 children, 30 nursing children and 70 children between the ages of 1 and 3 and a half. This building was located next to the factory’s social facilities, so that the women employees could easily attend to their children before working hours, and its project included net fencing and a hedge, ample garden and lawn, with a children’s playground on the West side, with sea-saws and other toys, and many trees. In addition to the milk dispensary, nursery, a “room for the older children”, canteen, butler’s pantry, kitchen, storage room, laundry, toilets and offices, the facilities also included a workshop, a doctor’s office, and an isolation room for sick children, among others. The pavements of the kitchens, toilets and laundry were in tiles made in plaster of cement and marble sand, white tile panelling on the walls, and all other walls were finished with vitrified washable paint up to door height. The interior of the facility was decorated with simple, et functional furniture, all in anti-toxic and easy to wash materials in the service areas (tops and counters in the pantry and kitchen), “so that all meals can he processed as hygienically and cleanliness as possible”. In addition to the hygiene and safety concerns, this project by Jerónimo Ferreira Reis also clearly showed aesthetic awareness, for example, in the façade design, where the main surfaces were cladded with lazes ceramic tiles and the remaining mortar elements were painted with plastic paint in the colours of the surroundings (AMSMB/CMVNG - Processo de Obras particulares em nome de D. Ferreira Ld.ª, 1944-1951).

Final remarks

While nursery institutions were part of the group of institutions that cared for pre-school aged children, the age limits allowed and their educational guiding philosophies were not always clear. The fact that they welcomed very small children puts them in an assistance-educational group, one in which new pedagogies were adopted very gradually, mostly based on the education given by the mothers’ example and educational practices of their supervisor, and on the socially prominent and regulating philanthropy. As they were governed by associations, there is hardly any documentation on the children’s every day issues besides their food, hygiene and donations received.

Established in the 19th century to provide for the increasing social needs as a result of the women entering the labour market, the number of nurseries was always disproportionate in relation to the actual needs, the most glaring example being the region under study. As a Providence State was lacking, the bourgeois and aristocratic philanthropy, the Masonry and the religious assistance supported the nurseries until the Estado Novo period, which tolerated them as a lesser evil in the urban context.

While up to the Republic period nurseries were part of the process then called the “dawn” of education, during the dictatorship period nurseries hid the miserable ones, avoiding the “sad spectacles for society”. The highly welfarist nature of education in nurseries heightened during the Estado Novo, at a time when the very few institutions in operation were based, above all, on the idea of charity, being less demanding, not only in terms of staff qualification, but in the actual architecture of most of these facilities.

The relationship of eugenism with the emergence of nurseries was quite evident until mid-20th century, when Childhood became a “legislated” matter in the “Declaration of Children’s Rights”, and political discourses firmly rooted in social sciences have taken to the in/equality of children upon entering school.

This study reflects the overall Portuguese urban context. First and foremost, nurseries in Vila Nova de Gaia, regarded by most stakeholders as charity, welfarist institutions, were sort of invisible in their efforts to promote the special aspects of early childhood. Moreover, despite their promising start in late 19th century, the nursery network expansion contracted throughout the 20th century, and the resulting facilities were mostly due to the initiative of factories and businesses, rather than philanthropic and when they first appeared, and always concentrated in the parishes of Santa Marinha and Mafamude. There is no information about the “child carers” or nurseries in rural parishes, which form the largest part of the territory, and in most cases children accompanied their parents to work.

texto en

texto en