Introduction

We seek in this text, which is part of a broader2 research, to understand the guidelines of doctors to promote hygienic education in the João Barbalho school, a structure created to be the model of republican school institution in Pernambuco. The years from 1922 to 1931 cover the composition of this group and the process of expansion of this type of school institution in the state. In the period, three educational reforms were conceived by Ulysses Pernambucano (1923), Carneiro Leão (1928) and Aníbal Bruno (1931) in Pernambuco. Such reforms sought, in addition to implementing the Scholovist ideals, to establish social distinctions based on studies of racial theories disseminated in our country, aiming to solve the “Brazilian racial problem” (ARANTES, 2018).

We are theoretically based on studies in the area of cultural history and the history of education in Brazil. We analyzed sources such as instructional documents, school group reports, educational legislation, education journals and hygiene medicine theses circulating in Pernambuco during the study period, located in the archives of the Jordão Emerenciano-APEJE Public Archive, of the Presidente Castelo Branco-BPE Library, and the LAPEH History Research and Teaching Laboratory, linked to the UFPE History Department. For the process of source analysis, it is necessary to understand the context of its production, considering beforehand that they are not absolute and undisputed truths, that is, as Le Goff (1990, p. 564) states, “there is no document -truth. In the end, every document is a lie. It falls on the historian not to play naive. Therefore, when dealing with the reports prepared by the governors, the directors of public education or even the regulations and regulations of education, for instance, it must be considered that all have their origin in some legal act. Thus, as stated by Faria Filho (1998), they mean the law itself in its dynamics of realization and, therefore, of the ordering of sociocultural relations. In this respect lies the fact that these documents were used as significant indicators so that the authorities could verify whether the law was being obeyed or not.

It was in the context of the historiographic renewal movement of that the History of Brazilian Education also began to address the issue of schooling and how it was institutionalized. Among these themes, emerged the school groups and the school culture present in these educational spaces, which, according to scholars in the field3, were responsible for inserting a large portion of the population in the world of formalized knowledge. In this sense, Souza and Faria Filho (2006, p. 22) mention:

The history of school groups arises in the 1990s as part of the movement of renewal of studies in the history of education and the confluence of two themes or avenue of approach to which historians have turned: the history of educational institutions and the interest in school culture. It can be said that this story meant a rediscovery of the primary school investigated on the basis of new epistemological approaches and interpretations and explored in a multiplicity of themes and objects.

Also, according to the authors cited, the examination of Brazilian production on school groups reveals the markedly regional character of the studies and a major concern with their origins; that is, the timing of this primary school modality in each state resulted in a strong emphasis on the First Republic. They estimate two groups of studies: in the first, there are those that, in the broader scope, turned to the characterization of school groups and the constitution of their implementation in the states; while in the second, there are studies of monographic nature, focused on institutional history, focusing on a school or a group of schools, usually the first or the first in a given locality.

These institutions joined the efforts of the Brazilian elite in the promulgation of a “civilizing ideal, often riddled with civic and patriotic references” (VIDAL, 2006, p. 10), which sought to strengthen national identity. Vidal (2006) also highlights that:

The administrative and pedagogical reorganization of the elementary school provided by them focused on the reordering of school times and spaces, the expansion of the curriculum, including encyclopedic subjects, and the redefinition of the place occupied by the school in the layout of cities, since the School Groups were constituted as an essentially urban reality. [...]

However, if school groups were of particular importance in the symbolic construction of the Brazilian primary school and in the production of childhood history in Brazil, it is not true to say that their influence was unique in the period up to the 1970s. hegemonic primary school, in the 1920s, another was associated: the New School (VIDAL, 2006, p. 10, emphasis added).

Therefore, the school group represented a new model of school organization, characterized by the serialization with the division of students by classes, considering the age and the levels of knowledge intended uniformly. In this sense, one of the factors that interfered in the organization of these institutions was the hygienist theories spread by doctors for some time, but which gained emphasis in the same period of implementation of school groups. Doctors advocated respect for hygiene in the construction and maintenance of school buildings, “from the physical facilities, furniture, organization and selection of teaching methods and teaching materials, to the preservation of the health of the student and the school community” (JORGE, 1924, p. 28). Such prescriptions greatly influenced the organization of education, which intended to encompass from its methodologies and contents to the formation of the teacher, the spaces and times of teaching and the relationship with children, families and the city.

As part of the emerging culture in this new form of school organization that was the group, physical education took on the mission of “regenerating race and preparing for work,” as Vago (1999, p. 30) demonstrates, thus contributing to for the republican social project that took the school group as a social laboratory that “a beautiful, strong, healthy, hygienic, active, orderly, rational body should be cultivated, as opposed to that considered ugly, weak, sick, dirty and lazy” (VAGO , 1999, p. 32).

Thus, medicine came into the school space to contribute the scientific apparatus necessary to the task of regenerating the nation, with physical education as an important ally. In the meantime, medical discourse came to be perceived from both hygiene issues and issues involving eugenics, especially in the first decades of the twentieth century in Brazil. In Pernambuco, some practices were implemented to establish the physical and mental conditions of students and their education. “As part of these processes, we highlight the executing testing of anthropometric measurements such as: weight index, robustness index, vital capacity and thoracic perimeter, etc.” (ARANTES, 2018, p. 248)

Therefore, hygienist doctors played a decisive role in a debate more broadly about interpretations, dilemmas, and directions of Brazilian society that aimed at a healthy nation, as is stated by the historians of education and the history of physical education4.

1. João Barbalho school and the regulations for its operation

Even though Law 1140 mandates the creation of school groups in 1911, the sources we work with report that the creation decrees of the first school groups date from 1922. The João Barbalho School Group was established in the capital, Recife, at that time to be the model establishment of Pernambuco. But who was João Barbalho?

João Barbalho Uchoa Cavalcanti, a native of Sirinhaém, the heartland of Pernambuco, was born on June 13, 1846, in the Coelhas mill. He was the son of Empire Senator Dr. Alvaro Barbalho Uchôa Cavalcanti and Ana Maurício Vanderlei Cavalcanti. He made his preparatory studies at the Pernambucano Gymnasium and the College of Arts. In 1863, enrolled at the Faculty of Law of Recife graduating as a Bachelor of Legal and Social Sciences in 1867.

After exercising for some time (1868 to 1872) forensic law, he was appointed Public Prosecutor of Recife and, shortly after. Later, appointed Chief Curator of Orphans. His career as Inspector General of Public Instruction of the Province of Pernambuco began in 1873, a position held for 16 years at the same time, showing that this empire intellectual circulated through various areas of influence, occupying command position, thus being aware of the debates that were circulating (BEZERRA, 2010, p. 81-82).

In the 1923 yearbook of education, which was in force in the state of Pernambuco, the new teaching regulation contained “the big issues for primary education” that needed to be resolved. It is the location of the house and the pedagogical material for the operation of schools. According to the rapporteur of the document, Aníbal Gonçalves Fernandes, responsible for the Justice and Public Instruction Business Bureau:

We find most of our schools lacking resources and poorly installed. The João Barbalho school group worked in an outhouse of Gymnasio Pernambucano, in an inappropriate place, inconveniently located and in the vicinity of the normal school that holds an application course with 7 primary classes. (PERNAMBUCO, 1923, p. 4, emphasis added).

Subsequently, the João Barbalho School Group started to operate in the building of the former Department of Health and Care, completely renovated and adapted. The building has been expropriated for public utility and has come to be considered “a primary education establishment that honors our culture and our progress” (PERNAMBUCO, 1923, p. 4). It appears from the same document that that group was created by Act No. 324, of June 2, 1922, located in the Capital Recife, in the Boa Vista neighborhood, with six chairs.

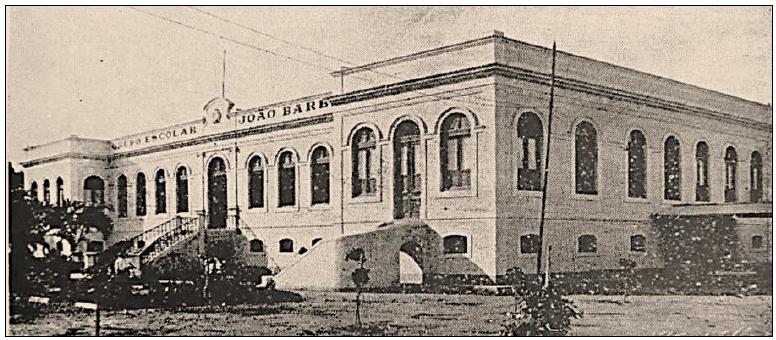

Helena Pugô was the director and the teaching staff was formed by Julia Tavares Cordeiro de Campos, Aspasia Cavalcanti Marques, Eunice Gama Marques, Noemi de Goes Cavalcanti, Maria das Dores Klutzeuchell, having as caretaker Miguel Francisco dos Santos (PERNAMBUCO, 1923, p. 62). In the following image of João Barbalho's façade, we realize that the architecture of the institution was monumental, designed to be the model school group of the state. Still looking at the image, we noticed the presence of the walkway that connected the main building of João Barbalho to the kindergarten Virginia Loreto. In the following image, it is possible to see more clearly said walkway.

Source: Jordão Emerenciano Public Archive Collection / APEJE (1923, s.p.). (Public Domain).

Figure 1: State School Group João Barbalho, 1923

As is well known, since the second half of the eighteenth century, debates have been staged around the structure of spaces and the fixation of school times. However, it had to arrive until the end of the next century for this reality to materialize in Brazil. This occurred first in São Paulo, with the creation of the first school group and, later, in several Brazilian states (FARIA FILHO; VIDAL, 2000). Linked to the concern with school spaces was at issue the hygienic precepts that the school environment should present. This discussion intensifies in the first half of the twentieth century, raising concerns about the construction of buildings, courtyards, the conformity of the internal space of classrooms - responding to the rules of lighting, air circulation, furniture, arrangement of furniture - to student education consistent with hygiene precepts.

It was in the midst of these discussions that school groups were created to be the “temples of civilization. ” (Souza, 1998). Thus, the discussion begins about the best type of architecture that a school group (the republican school model) should present. The school architecture thought at that time, within the new administrative political regime, intended to deny certain architectural standard considered archaic. “Named the pestle, the new architectural model enabled the cultural self-protection of a social class in shaping the urban physiognomy, which becomes conglomerate, angular and surrounded on a cosmopolitan air. ” (MONARCHA, 1997, p. 104).

Therefore, the architecture of the primary school should represent certain spaces for early childhood education and, furthermore, demarcate, through the distribution of the children and professionals, specific places and actions for each of them. Above all, the architecture of the school groups was intended to be monumentally established (SOUZA, 1998, p. 124) to meet the required educational ideals as well as the intentions of the republic through social progress intended with this particular type. Recognized as a school group.

In this context, Pernambuco felt the need of school buildings and furniture that met the requirements of the medical school legislation adopted in countries considered “advanced in civilization” (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 177). In a report of 1924, the principal of João Barbalho, Helena Pugó presented to teacher Deoclécio Cesar de M. Lima, school inspector of the 2nd division, the situation of the school that year, as noted: “In compliance with the provisions of art. 60, no. 14, of the current regulation, I pass your hands the report as was the case in the School Group headed by me, during the current year. ”(PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 177).

The principal begins her report, stating that in Pernambuco there was something different from what happened in the other states of our country. There was no school together, no school group in the capital, while inside there was something inadmissible, she said. Let's see:

Until mid-year 1922, the primary instruction of Pernambuco was out of ordinary, perhaps unique throughout the country. In fact, in the urban part of the capital, there was neither a school gathered nor a school group in which full primary education was provided that would enable pupils to seek secondary courses successfully.

This contrast was even more remarkable because, in the suburbs and in the inland municipalities of the state, already assembled groups and schools were already installed, developing, besides the program of the 3 classes, the fourth class or complementary.

To remedy this lack, quite notably Mr. dr. Severino Pinheiro, then acting as governor of the State, with act no. 324 of June 3, 1922, founded the “João Barbalho” Group, honoring me with its board (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 177, emphasis added).

Even with the creation of the “João Barbalho” school group, the operating conditions were not the best. According to the director, the lack of appropriate buildings and the serious moment of political crisis that the state was going through did not allow a better location, and the Group was set up in a outbuilding of the former Gymnasium, and precisely at the back with entrance by Union Street. PERNAMBUCO, 1924). It is stated in the aforementioned 1924 report that

Despite having large halls, the Group was badly placed because it was situated in a very remote location far from the inhabited center and without being able to count on a considerable number of the school population in its vicinity. Although, for these reasons I had an excellent teaching staff who assisted me, everyone was pessimistic about the success of the new institute: they all thought it impossible to obtain regular attendance: they all advocated its next dissolution. But we did not lose heart and, all teachers and principals, we increased our efforts to ensure that the result of the first school year (covering only 5 months) was a stimulus to families who, despite the faraway location, would prefer it in the coming year (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 178).

In the school year of 1922, the registration, which was not considered satisfactory, increased significantly and “João Barbalho” had the pleasure of counting among his pupils, especially of the third and fourth grades, children who were submitted to huge sacrifices to come from. Locations far from the center of Recife such as Várzea, Dois Irmãos, Olinda, Afogados, Beberibe, Cabo and even São Lourenço da Mata, to attend the classes with regular attendance. Even so, the João Barbalho Group's location was considered an obstacle to its development in the opinion of its principal Helena Pugó. Let us see:

Right From the first visits you made to the group on the premises of the school, your clear vision and competence showed you the need to give to the only state institute that, in the urban part of the city, distributed integral primary education, a more dignified series, more centrally, more in accordance with the demands of instruction and the relevant efforts already demonstrated by the teachers and students of “João Barbalho” (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 178-179).

Still in relations to the location of the group, the principal mentioned that “João Barbalho” had the chance of establishing itself on October 19 1923 in the building where the Department of Health and Hygiene functioned for many years and which, undergoing renovations, soon became the model primary education institute that represented the pride of our capital and Pernambuco. According to the principal, even in maintenance work and renovation no school day was lost. This was due to the goodwill of the teachers and students, who sought to become worthy of the benefits of government. Classes were held on a regular basis and examinations were conducted at the regulatory time, showing highly satisfactory results.

So much so; Both students have taken advantage of the lessons we have given them that, in the high school entrance examinations (regular and Gymnasium), nine of the students presented by this Group have been approved, which is undoubtedly admirable given the great percentage of failing exams (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 179-180).

Also, during the school year of 1923, on November 19, this group, commemorating the anniversary of the republican flag of our country, instituted the Feast of Trees. Before the Governor and the leading federal, state, and municipal authorities, they “planted the first flowers in the garden that, today, both beautifies and brightens the front area of the Group. ” (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 181).

Regarding school exams, during the course of the 1923 school year, the board informed the society and all students that only would be accepted those students who:

During the year, they had shown attendance, achievement, and good behavior, and so did, because she was convinced that it was absolutely necessary that the examinations be carried out with the utmost severity and careful choice in order to prevent some of the most struggling student and those who have shown low performance may, by simple chance, make good tests and achieve a not deserve approvals (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 183).

In the examinations carried out, of the 162 students enrolled in the four classes of primary education, only 119 were approved. The principal said that she was pleased with the results of the exams because “she could see the magnificent results of the efforts made by the respective teachers who, all without distinction, did everything to make sure that their students enjoyed the time devoted to their studies. ” (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, pp. 183-184). Most notably, “noteworthy were the results obtained by the 3rd and 4th-grade teachers, Naomi de Goes Cavalcanti and Maria Emilia Silveira, who presented numerous and perfectly prepared classes” (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 183-184). Regarding the state of education at the time, the secretary of education said that:

The problem of primary education has lately been the subject of study by educated governments since it is universally known that the greatness of a country is in direct proportion to its people's education. Pernambuco, being unable to remain indifferent to the movement that operates in the country, in favor of popular education, it also unfurled its banner to combat analphabetism, beginning a new era for the school life of the state, (...) the primary school in line With the new pedagogical orientation, it must accompany the march of social evolution. It also proposes, in addition to developing the inventive faculties in the child, and shaping their character, so that when it leaves the school, it is acquainted with the basic facts of life. Essential aspects to drive with energy and dignity (...). (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 133-134, emphasis added).

The above text demonstrates the concern that the rulers across the country shared, that education was the solution to enter the desired development with the proclamation of the Republic. Thus, the new direction for teaching was associated with this concern, with the aim of character formation and illiteracy eradication.

Within a few years, João Barbalho School Group has been able to attract the confidence of the inhabitants of the Boa Vista neighborhood, that began to see it as a leading school. Thus, this school became the model of schooling organization in the state of Pernambuco. It also started to operate the Virginia Loreto Kindergarten (PERNAMBUCO, 1924), as already mentioned. In addition, at this school was adopted “the new method of scientific pedagogy”, conceived by Dr. Maria Montessori.

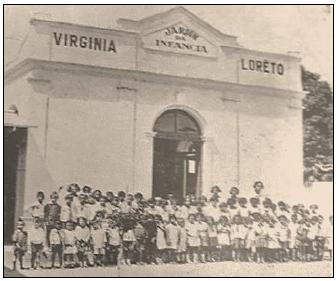

Source: Jordão Emerenciano Public Archive Collection / APEJE, Pernambuco, (1923, s / p.) (Public domain).

Figure 2: Kindergarten Virginia Loreto - part of the João Barbalho School Group

Looking at the image above, we can see the children who attended it were poor, since many of them have bare feet and very simple clothing. It is also possible to perceive the presence of some black children.

Virginia Loreto Kindergarten was highly praised, especially from the principal of João Barbalho School Group, Mrs. Helena Pugô. Here's an excerpt from her report:

We want to express our gratitude to the head of public instruction in Pernambuco, who has done so much to make this school a delightful place where the child looks for it spontaneously because it feels good and satisfied after much learning (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p 184).

Then continued to point out that the results obtained in Virginia Loreto's first year of operation were extraordinary, “for the children who, at the age of four or five, entered it without any knowledge, reached the end of the year with all their senses developed and refined, and this because of the comfort and affection they found in it and the unique and practical Montessori method. The material used was designed by the Italian educator for early childhood education, assured the principal.

In fact, superior to all similar ones known until today and with excellent practical results. It indeed represents the emergence of pedagogical achievements: teaching by educating. This material, the child quickly acquires a sense of proportion that lacks in it. Also, it learns not to confuse the perspective of things. It is a playground for the soul and a stimulus for the mind. (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 184-185).

Mrs. Helena Pugô, also mentioned that the little children were very interested in the beautiful toys that constituted the teaching material, learned to calculate and read, educated themselves by all vehicles and developed all the senses: sight, smell, hearing, touch, the sense of form and weight, The letters in the muscular sense, all contribute to the considerable amount of notions they acquired. In the Kindergarten Virginia Loreto

The children came into the school laughing cheerfully, during the classes they learned with joy and enthusiasm when they leave school, they already missed it, as well as the teachers who served them as loving mothers.

(…)

Today at school is a paradise. For children do not have appropriate schools, there are real gardens.

There is no one who does not become sensitive and envious as soon as you enter the enchanting environment of a kindergarten. The children are full of health and intelligence. They play and learn, or rather learn by playing. What a joy! How wonderful! (PERNAMBUCO, 1924, p. 184).

Analyzing the speech of the principal of the institution concerned, we can not forget that the source analyzed expresses the opinion of a subject only within the much wider school universe that includes doctors, inspectors and teachers. However, the emphasis we have given here to this kindergarten is due to the fact that this type of school activity was linked to the processes of hygiene since the first contacts that children had with the school universe and also the first notions of hygiene were worked by the teachers. Thus, the teachers provided simple guidelines on how to wash their hands, cut their nails, brush their teeth; comb hair and combat lice; not throw trash on the floor, among many other guidelines, which are now considered essential. We can not forget to mention the social representation of the figure of the teacher as a loving mother. This type of image is still common nowadays. However, the male figure being something unacceptable in the acting education of very young children.

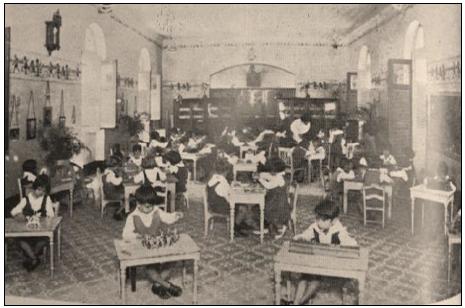

The following is another image of the kindergarten belonging to the João Barbalho School Group.

Source: Jordão Emerenciano Public Archive Collection / APEJE, Pernambuco (1933, s / p.) (Public domain).

Figur 3: João Barbalho school group - Kindergarten Classroom

In the image above, we can see that the students seem to perform playful activities - some of the children individually, others in groups at their tables. However, due to poor image quality, we could not identify the presence of black children in the classroom.

The next point we will address next is the hygienist medical precepts to be implemented in school groups, such as is the case of João Barbalho.

2. Hygienic Guidelines in the João Barbalho School Group

We know that, based on hygienic ideals, Brazilian doctors sought to transform Brazil into a civilized nation and, therefore, needed to solve the problem of social, moral, intellectual degeneration that they believed existed and prevent the much-needed progress of this civilization. In this sense, Schwarcz (1995, p. 198) states that the mixture of race was understood as responsible for the production of a hybrid type, physically and intellectually inferior. Therefore, a synonym for not only racial but social degeneration, it was from miscegenation that madness was predicted, and crime was understood. Only then were race improvement programs defined. Medical knowledge was progressively assigned the role of tutoring and sanitizing nationality; in this task, doctors have often taken an extremely authoritarian and violent approach in their interventions. According to one of the slogans of the period - "Prevent, before cure" - the evils should be eradicated even before their manifestation.

This type of medical science has been called “social medicine” and has been structured since the nineteenth century, trying to demonstrate the cause of the disease was the social reality of capitalism and, therefore, it was not enough to intervene “in the individual or social collective, as postulated clinical medicine. Health would be achieved and preserved with the change of society. It is the social structure that explains the emergence of diseases. ” (SOARES, 2000, p. 52)

In this context, physical education was inserted in the daily life of schools, in our specific case, in school groups, initially through gymnastics, closely linked to the objectives of this social medicine. Thus, “On the one hand doctors saw in the physical education of young people a strategy of disciplining and guiding healthy habits. On the other hand, the first instructors saw medicine as the necessary scientific reference to legitimize their practices. ” (GOIS JR, 2013). Still on gymnastics, Soares (2000, p. 46) informs us that it is a “technical model of body education”.

An expression of speech and practice of power reveals its aesthetics which can be translated by the uprightness of bodies, the search for an aristocratic haughtiness tinted with bourgeois utilitarianism. The body is understood as a set of forces capable of setting in motion precise determinations, containing and suppressing desires, preserving energy. Thus, it emerges as a necessary garment for a body that presents itself in a nakedness not of clothing, but of morality. In its precepts, there is a clear perception of the relations between the physical and the moral, between physical and moral normality.

In order to fully comply with Law 1140 of 1911, it was necessary to carry out a broader reform, regulating and standardizing how the new pedagogical practices should be implemented, especially those related to the problem of hygiene in Pernambuco schools. Thus, in addition to the traditional officials who were in charge of controlling and inspecting the operation of schools, such as the inspector general, the school inspectors, and the teaching delegates, the activity of the school doctor was instituted in 1912. The activities and obligations of the school doctor were reiterated in the reform that would take place in 1926. This professional should be one of the “commissaries of Hygiene, ” whose task was to perform the school medical inspection. It was appointed by the inspector and was to act on the 4th grade, whether in public or private establishments. In other instances, the medical inspection service would be performed by the commissioners of the respective districts. These doctors were responsible, in addition to the vaccination and revaccination service, finally, everything that referred to school hygiene (PERNAMBUCO, 1912, p. 18-19).

The teacher needed to be a doctor's partner for hygienic inspections, although it was also a target of the sanitation processes in the schools. The partnership foreseen in the regulation between the doctor and the teacher tells us about the speeches of Carneiro Leão and Ulysses Pernambucano when they affirmed that pedagogy and medicine should go hand in hand for the success of a hygienic education.

In addition to the doctor, another position created in 1923 was that of visiting women, on the occasion of the Reform idealized by Ulysses Pernambucano. These are nurses who should provide assistance to the medical school inspection, whose function would be to ensure the health of the students. For this activity should be taken advantage of those who already worked in the Department of Health and Care and were charged with:

(a) Work in or outside schools under the guidance and direction of the medical inspection;

(b) Visit the families of schoolchildren, seeking not only a more accurate knowledge of the heredity of the students and the means in which they live, but also to advise and guide the parents in the practice of good hygienic habits (PERNAMBUCO, 1928, p. 11).

Ulysses's proposal to sanitize schools included the exclusion of children with infectious diseases, and so-called abnormalities, so as not to hinder the development of healthy children. From there, Ulysses gives us the school models for unhealthy. In this process of identifying the unhealthy, the role of the school doctor appears as a decisive subject in the educational scenario. In this context, we infer that the number of black children contained among children diagnosed as weak should be large. If we consider that the racial factor was taken into account when conducting psychological tests and other types of examination that aimed to establish the biotype of the student from Pernambuco, and that the results, in most cases, left blacks in a weak position to whites, our inference is grounded.

In addition to the general hygiene measures that should be observed in the construction of the schoolhouse, it was necessary to strictly observe the hygiene measures intended mainly for the classes, that is, the classrooms, as there was a consensus among the authors who discussed hygiene at the time when classrooms were rectangular.

The number of students who had to meet in these classrooms should be stipulated and always subject to a calculation, “the proportion between the students, and the size of the room where they will be staying, and the advantages that come of these observations, in the double hygienic and pedagogical point of view. ” (JORGE, 1924, p. 26, italics added). Thus, the classrooms should comfortably house a group of 40 students and should have 62m2 so that each student had 1, 25 m, and had 5 cubic meters of space. Hygienists thought that the cubic space could not be less than 6 m (MOSCOSO, 1930).

Among the methodology and guidelines that should be adopted in schools in the period of 1929, we highlight the following passages:

(...) Now, to know the vocation of students, it is necessary to individualize education as far as it is compatible with collective teaching. The best teacher is the one who knows its students. In order to do so:

(...) b) Take separate classes for healthy students and students with low level as (mentally weak, repeat student, absent) and the very intelligent.

c) divide the elementary classes into sections A, B, C, D, so that the skills of the students show a few differences in each section.

d) know the internal characteristics of each student, their way of being; study the types of minds: visual, kinesthetic, imaginative, reflective, logical, aesthetic, selfish, selfless, euphoric, naive, depressive, willful, abusive. (PERNAMBUCO, 1929, p. 5).

The separation of students into healthy, intellectually disable and very intelligent, regulated by the state of Pernambuco, indicates to us the consonance of hygienist ideals and precepts that were so widely studied and disseminated by the intellectuals from Pernambuco. For this purpose, psychology and sociology were allied with professionals involved in education, as was the case with school doctors, visiting nurses and teachers themselves to verify the physical, mental and moral states of children attending schools during the study period.

In line with the precepts of the reform of Ulysses, Pernambucano was the 1928 Carneiro Leão Reform. Its creator was concerned, among other issues, with the problem of abandoned street children, as he believed that material and social poverty could cause a problem: the impoverishment of the blood. It was emphatic on its points, stated that:

The problem of abandoned childhood is one of those that worry the most educated people everywhere. As civilization grows in intensity, and the struggle for life reaches its fiercest aspects, the misery and anguish of most men increase. All these people, whose lives drag on painfully producing much less than they need, should endure the consequences of imbalance, compromising, by the impoverishment of their blood and weakening their resistance, for the generations to come. Sometimes these generations are born ruined; Others, however, are promising, and only abandonment, suffering, physical and moral penury will dissipate in the first years of existence. They are the children of misery and pain. Out of them will come out on a large scale the criminals, madmen, beggars and all the monsters that ruin the species and sharpen and poison life (CARNEIRO LEÃO, 1919, p. 238 - 239, our emphasis).

Analyzing the above passage, it is evident that the author's statements can be considered eugenic because, in this context, hygiene joins eugenics to combat the causes of social degeneration. From the eugenic perspective, the causes of humanity's degeneration were hereditary. However, alcohol, nicotine, morphine, and venereal and infectious diseases were considered to be racial poisons that caused permanent degeneration and, in the long term, would determine the existence of a sick and worthless nation. It was this kind of thinking that contributed to the elaboration of the idea of race and all that it represented at the time and still echoes today (STEPAN, 2005).

According to the documents we consulted, there was a great debate about the ideal number of students for each classroom. The French admitted 50, the Americans 40 to the lower classes, and 50 to the other classes. Germans, Belgians, Swiss and Italians defended 40 per class. However, some hygienists in Brazil proposed reducing to only 30 students for each classroom. (PERNAMBUCANO, 1918).

Later, at the time of the 1928 Reformation, Aníbal Bruno, responsible for implementing this teaching reform and proposing new designs for the education of Pernambuco, proposed an instruction that promoted the technical, intellectual, and moral formation of man, which transformed it into value. Affirmative in democratic social life. For him, this was the “mission of the school in the way that modern orientation assures it.” In other terms:

It creates the social level of the popular masses, but it is still the foundations of the differentiation of the ruling elites, not of the artificial elites created by politics or economics, but of the natural elites in which the values of the race are added.

And in the education that Brazil will have the only effective means for its whole, social, and economic reconstruction. Because, as a post-war author said, restoration is a problem of organization and education, let's say social technique and psychology (BRUNO, 1930, S/p., emphasis added).

Analyzing the excerpt above, we realize that the author believed in the existence of natural elites, that is, that there were superior and inferior races, communing with eugenic thoughts that circulated in Brazil during the period under study. Continuing his speech, Hannibal emphasized the role of education. He said that if the new democracy aspires, as it should, to be based on conscious public opinion, it is in the systematic education of the people that it will seek it. Hence the power attributed to the school by the author. Let's see:

The physical regeneration of the race, the development of character, the integral culture, in short, the valorization of man in Brazil, only the school can promote, with its powerfully constructive, biological and social action. Only it can create a shared social ideal for the conscious and harmonious cooperation of all for the general good. And the revolution for this educating work will consume its commitment quite clearly (BRUNO, 1930, p. 8, emphasis added).

In order to meet that obligation, the school should provide full-time education. In this sense, it says:

If there is a work that should gather the votes of all the voices, that in Brazil will rise for the greatness of the country, that should provoke the unison cry, an irresistible movement of all living forms of the country, this is the education of the people. A central problem, encompassing all the issues, in which all the yearnings and grand aspirations of the race merge, the open and bright air of freedom, the majesty of justice, the abundance of wealth, the broad prospects of health, The Prestige and national dignity, the education of the people, in itself, is a government program. Extended and integral education, within which process of physical regeneration of the race, character formation, cultural survey of the people, technical preparation of the national worker. (BRUNO, 1930, p. 14, emphasis added).

The above passage expresses concern for the education of the people, just as Carneiro Leão also expressed. The difference is that Hannibal proposes an integral education, including in it the preparation of the worker. He also proposed that his education tends to physically regenerate the race, which justifies the processes of racializing the students, which took place in the elementary schools during his term as head of Pernambuco's technical board of education.

In the management of Aníbal Bruno there was a concern to guide physical education so that it fit the “rigorously scientific molds. The justification for this concern was explained as follows:

[....] More than in any other people, perhaps, it is inexorable to seriously consider among ourselves the physical basis of the race. If in the great Northern Republic, the health, the physical capacity of the nation, is considered the basis of all social progress, much more attention calls for physical education in Brazil, where accumulated anti-hygienic causes have created a diseased race, which is must at all costs rescue (PERNAMBUCO, 1931, p. 9, emphasis added).

In this context, it was believed that the measures adopted by the State Department of Education "placed physical education in Pernambuco in a way that was superior to that of any other similar organization in the country." (PERNAMBUCO, 1931, p. 9). To this end, a corps of physical education inspectors oversees the entire service. Specialized physical education monitors directed the exercises and a teacher and an assistant were distributed to each school group under the superior guidance of the General Instructor of Physical Education.

The preparation of these specialized teachers took place in a regular course that formed them with theoretical classes and exercises, governed by the General Instructor. The candidates received principles of anatomy and physiology applied to physical education, fatigue physiology, effort hygiene, pedagogical biometrics, taught by medical inspectors of the service. The children were gathered for the exercises, not in school classes, but in similar classes, according to the anatomical-physiological age, and there were also special classes of corrective gymnastics and respiratory gymnastics for the weak and intellectual disability. Therefore,

Each student is the subject of a complete clinical and biometric study, on which is based the individual form of physical education, and the medical examinations are periodically renewed, to verify the results obtained with the practice of the physical exercises (PERNAMBUCO, 1931, p. 10).

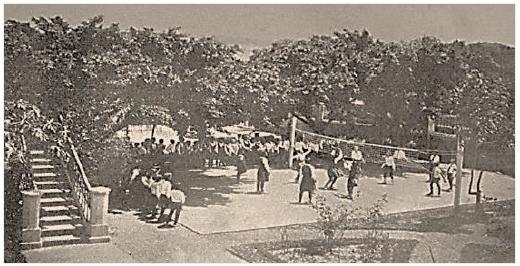

It is worth mentioning that these tests consisted of psychological and anthropometric tests whose results were racialized, first by the Roquette-Pinto classification (Faioderm, leucoderm and melanoderm) and, later, as whites and mulattos. At that time, in Pernambuco, specific areas were also adapted for the practice of physical education, such as: running tracks, gymnastics and games, exercise and recreation facilities, according to the most modern orientation, in all school groups. This organization should culminate in the Physical Education Park, the construction of which was widely preached by the Government in a large central area of the city, where children from all schools would find complete facilities for games and exercises, the foundation of the health and vigor of the younger generation. The following images express moments of Physical Education classes of the João Barbalho School Group. In the pictures, we can see boys and girls playing volleyball on the court of that school and practicing gymnastics in a wooden maze, respectively. Due to the quality and the angle of the image, we could not identify the presence of black children in these activities.

Source: Jordão Emerenciano Public Archive Collection / APEJE. (1931, s./p.). (Public Domain).

Figure 4: A Volleyball Field - João Barbalho School Group, 1931

Source: Jordão Emerenciano Public Archive Collection / APEJE. (1931, s./p.). (Public Domain).

Figure 5: João Barbalho school group - Physical Education

As we can see in the images above, there was a general orientation for physical exercise to be practiced outdoors, in areas that were “immediately adapted for this purpose and, during bad weather, in sheltered pavilions and other places, with sufficient fresh air and conditions of perfect hygiene. ”(PERNAMBUCO, 1931, p. 109). Exercises should be performed daily at convenient times before class. Below are some determinations/guidelines for the activities:

- The monitors will direct the exercises, under the general guidance of the teacher of physical education and the frequent supervision of the medical inspectors, who will try to adapt the practices to the individual conditions of the child, creating classes for corrective gymnastics in cases of deformation, asymmetry, hygienic gymnastics - breathing exercises for the weak and motor rehabilitation for the intellectual disability.

- The physical exercises intended for girls shall be taken into account the special physiology and aesthetics of form and movement of the organisms for which they are intended.

- During the exercises, children will wear large and simple clothes and shoes with flexible soles, according to the standard indicated by the Inspector (PERNAMBUCO, 1931, p. 109).

From the reality approached here, it is possible to refer to Soares's (2000, p. 46) statements when he states that “gymnastics was revealed as a singular intervention technique strongly associated with the establishment of order and military order is undoubtedly its inspiration ”, thus intending a social and individual intervention that would start in the school supported by the scientific apparatus of hygienist medical knowledge.

Some Considerations

We realize that Pernambuco school groups were created late, compared to groups from other Brazilian states, as well as João Barbalho. In order to be in accordance with the scientific standards at the time, it was necessary to follow a series of guidelines from medical hygienists, ranging from the construction of school buildings to the care of students in order to ensure the physical, intellectual and moral development of the students. Students.

To ensure the proper operation of the school groups, such as João barbalho, among the guidelines that should be followed, we highlight the practice of physical education, anthropometric examinations, and intelligence tests to establish the students' profile for the constitution of homogeneous classes intellectually, physically and racially.

Therefore, to sanitize the school and, consequently, society, it was necessary that education and medicine worked together to save the nation and the Brazilian homeland that wanted to be healthy and regenerated, as it was present in speeches of intellectuals from Pernambuco who were responsible for the reforms that took place during the study period, among which were: Ulysses Pernambucano, Carneiro Leão, and Aníbal Bruno.

Among the modifications contained in the Pernambuco reforms was physical education as a significant mechanism, if not the most important instrument that was “constitutive of school culture and should contribute to the student growth in citizen,

texto em

texto em