We never saw him stopped. On the street, always in a hurry, hands full of wrappers. He would not stop, to avoid missing the time of his duties. [...] [He] was the personification of an original fighter, one that no longer exists.

José Clemente, 1950

Introduction

Nilo Peçanha (1867-1924) was the president of Brazil for fifteen months and one day. Between June 15, 1909 and November 15, 1910, however, the ideal of development and progress that marked the consolidation of the Brazilian republic was on the spot, especially with the creation of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade. The inclusion of industry and trade in the occupations of this organ pointed out the direction the economy would follow; and this allows understanding that, as a national and central guideline, the economic orientation would have impacts on social life. Industrialization and commercialization of manufactures, for example, would take place in urban areas of low population density (such industrial districts) and of high demographic density (central areas of the city and neighborhoods). In addition, it raised expectations of employment in these geographic and economic areas; which means, it was supposed to create demand for workforce that had a minimum degree of schooling.

Regulating production activities with the creation of a ministry required to think of workforce training as well. Trained employees were crucial to make production happen and succeed, by manufacture or commercialization. Dealing with industrial output, with sales and purchasing relations, with industry and commerce management, required personnel with specific skills, especially in the industry, where mechanics, electricity, hydraulics and metallurgy are highly demanded. On the other hand, skills related to writing (among others, readable and quick handwriting, typing and knowledge of contracts, minutes, memos, requests, invoices, and other documents language) and accounting writing (knowledge of books and forms of registration and other accounting documents etc.) stood out as subjects of school learning and policies aimed at public education. As a complementary action coherent with the ministry, Nilo Peçanha decreed the creation of elementary vocational teaching in public schools of capitals in the country (decree 7.566/1909) as well as schools for apprentices.

Vocational education stood out not only in government concerns, but also within civil society. A measure of its projection amid non-politicians is in events such as academic congresses. At them, educators and intellectuals interested in education presented theses such as those that structured the second edition of the Brazilian Congress of Primary and Secondary Education, held in Belo Horizonte, MG, in 1912 (from Sept. 28-Oct. 4).2 Theses on vocational education stood out among themes such as primary education (freedom and gratuity, for example), conditions, means and instruments (libraries and museums). As Rocha (2012, p. 231) said, the congress expressed an “overall” understanding of vocational education as something not “strictly linked to the masses”, but rather as a kind of teaching that “[...] must specialize, while maintaining links with secondary education.”

The debate in the congress considered vocational education for women as well, as one may derive from the following asked questions: “For a perfect education for women [...] in different moral, intellectual, physical, professional and social aspects, what means are needed to make it happen these days? [...] is it not advisable to recommend the foundation of the schools for mothers, schools aimed at household professions, vocational institutes for women?” (CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE INSTRUÇÃO PRIMÁRIA, 1912, p. 8, 27). Judging by these questions, turning women into professionals would have as a purpose to train them not only to hold professional positions opened up to female workforce, but also to take care of the family’s moral, physical and social integrity. Here is the essence of the so-called perfect education. Women were supposed to have no intellectual and manual skills, no moral values, no sense of physical care, besides lacking preparedness for social reality within of the public sphere, which means, being outside the household physical limits.

Those questions were the starting point for the debate in the fifth committee in the congress at Belo Horizonte city. Its members included teachers, priests and others with a doctor’s title. One of the teachers was being Benjamin Flores. A name less known amid names like Delfim Moreira and Estevam de Magalhães, Benjamin Flores stood out by the action. In the year following the congress, by founding a school aimed at the commercial sector and a school aimed turning women into professionals, he went from the discourse on vocational education to practical actions.

Such school for women was the subject of a broader study3 that certainly deals with its founder but in a diffuse way. Thus, this article aims to complement such study by grouping data that allow composing a biographical and professional profile of Benjamin Flores: his social and family origins, his education, professional performance, his own family and his death. This profile relies mainly upon what the press in the Minas Gerais state published on him as well as on what other states’ newspapers wrote of him. The article contains information coming from an interview with Teresa Flores Moura, granddaughter of Benjamin Flores who made available her family archives. A manuscript letter, a handwritten last wish note, photographs, newspaper clipping, school forms and others printed material provided an important input for this profile, besides an interview with a former female student of the school for women. Her account, her self-published biographical books and her personal and family archives helped to amplify the focus of this article on Benjamin Flores life and work as well.

Familial and educational background

Benjamin Flores de Oliveira was born in December 20, 1872, in Estrela do Sul, state of Minas Gerais. During his childhood, he lost his mother, Angela Augusta de Oliveira, a woman of Amerindian origins who stayed faithful to her culture by refusing to accept white man culture in its whole. “She resisted ‘til the day she died” - Tereza Flores said. His father, Joaquim Augusto Flores, a teacher who saw himself then in no condition of raising him on his own, soon enrolled his son in a boarding school (FLORES, 2016). Benjamin Flores was nine years old when became a student at the Colégio do Caraça school, in the region of Catas Altas, Minas Gerais. At the age of 19, he left.

As Andrade (2013, p. 168-9) says, to be able to afford studying at the Colégio Caraça was to be able to be in an institution whose status was that of the place to where the economic elite in Minas Gerais sent their sons to be educated. There, students become familiar with high literate culture seen as an element of social distinction and as a credential to enter higher ranks of social hierarchy in Minas Gerais. Not by chance, many former students would stand out in the political scenario of Minas Gerais. Colégio Caraça had as students more than two generations of sons a family from the city of Itabira, in Minas Gerais, who would hold successively high positions in the local government. More than three hundred students enrolled in the school from 1870s to 1890s, each one paying tuition and having to spend on books, for example. Annual costs of a student reached 680,000 réis in the 1870. Colégio Caraça was the first private school of Minas Gerais to focus on humanities. Its activities started in 1820, with a curriculum based upon classical antiquity content and with encyclopedic teaching and learning prevailing as pedagogical guideline. The course lasted seven years, with up to 28 subject matters. Latin was not only a requirement to finish it, but also source of knowledge. Latin expressions were mandatory to ornate the speech. Knowing Latin was essential to master and use Portuguese language with a high degree of style and adjusted to grammar and spelling rules.

A teaching and learning process founded on Greco-roman culture “[...] not necessarily meant a future professional specialization” for the students. The training the Colégio do Caraça school offered aimed at exams to enter into higher education; more than that, the meaning of studying at it had more to do with social classification: the school educated those who “were not like all” (ANDRADE, 2013, p. 167), that is to say, who were not like those who could not pay. In spite of this pedagogy aiming at exams, students had, too, a curricular basis that allowed them working as primary and secondary teachers, especially language teaching, whether Latin, Portuguese, English or French.

Perhaps because of a certain awareness of such non-professionalizing education is that Joaquim Augusto became concerned about the professional occupation of his son in this latter last years at the boarding school. A letter from 1891 shows his concern. It is noticeable the difficulties of communication between father and son. To hear from Benjamin Flores, Joaquim Augusto had to rely upon a network of friends and relatives in cities such as Formiga, Santo Antonio do Monte, Santa Abbey. He wanted to know in what state “he would be”, if he was facing hardships, if he was “in need, starving”, lacking clothes, if he was “esteemed”, “despised”… The letter was written on April 2, 1891, in São João Del Rei city, where Joaquim Augusto had met with a priest who talked about the professional future of Benjamin Flores. As Joaquim Augusto wrote in the letter, the priest wanted to know how Benjamin Flores was and told his father the “headmaster of Collegio San Francisco” had “reserved” a position as teacher for his son. This means Joaquim Augusto’s missive aimed to tell his son of such employment opportunity and of the need to reply it as soon as possible. The priest would be “eager to get know” his decision, because there were applicants for the job. He would make no move without an answer of Benjamin Flores, tough (FLORES, 1891).

Judging by the news mentioning Benjamin Flores name, after leaving the boarding school, his decision was to follow a path different from what his father desired. In December 1892, the Minas Geraeis newspaper (1892, ed. 238) included his name in call-note for preparatory exams, which allows inferring his willingness to become an academic. A year later, the same newspaper published a note saying he had taken hold of a management position in the mail company at Ouro Preto (MINAS GERAIS, 1893, ed. 340). In 1894, he made Latin exams and enrolled in the Ginásio Mineiro school, in Ouro Preto (MINAS GERAIS, 1894, ed. 34). In addition to applying for exams, he became Latin teacher, as told by the Minas Gerais newspaper (1894, 27 March, p. 4). Besides, he was invited to become examiner of exams in a primary school for girls (MINAS GERAIS, 1895). In September 1895, still working at the mail company, Benjamin Flores asked to be transferred to the mail company branch in Belo Horizonte. His request was rejected, though (MINAS GERAIS, 1895, ed. 247).

Even so, one might think that he foresaw another future for him Belo Horizonte, then Minas Gerais new capital. If it were not as a mail company employee, then it had to be in another way. In fact, he left the mail company probably between 1895 and 1896, for in June 1896 his name appeared in the newspaper as amanuensis of the third section of the Secretary of Interior, but still in Ouro Preto (MINAS GERAIS, 1896, June 20). In addition, he began to teach Latin in Ouro Preto Day School (MINAS GERAIS, 1896, July 2).

Keeping two jobs may have been a consequence of his limited income as civil servant. An expenditure table of the Secretary of the Interior in the first half of 1896 makes possible to have an idea of salaries based on the team of workers at the Ginásio Mineiro boarding school. Including salary and bonus, the amanuensis earned 900 réis a month; the door attendant, 700; one of the teachers, 1,500; the physician, 1,800; and the library secretary, 1,800, to name a few examples (MINAS GERAIS, 1896, Jan. 14, p. 3). Although there were possibilities of earning bonuses, sometimes they were not paid, as it happened to Benjamin Flores. He did not get the amount 30 réis due to extra work he did by replacing one employee at the Police Secretary. The Secretary of Finance understood that it was not due (MINAS GERAIS, 1896, Oct. 19). Moreover, it might be that the possibility of having a family made him to make an effort in two jobs. In December 1896, he arranged the paperwork to marry Thereza de Jesus Carvalho. She was 20 years old and he was 23 (MINAS GERAIS, 1896, Dec. 17).4

Sources: Diario da Tarde (1950, May 12); Tereza Cristina Flores Moura’s collection (unknown photographer)

Figure 1 Benjamin Flores and wife Thereza. Thereza and Benjamin had seven daughters (Benjamira Flores Arcieri, Dagmar Flores de Carvalho, Eunice Flores, Eliza Flores Pereira, Graci Flores Moura, Maria de Lourdes Flores Horta, and Neide Flores) and three sons (Antonio Lorêto Flores, José do Carmo Flores, and Moacir da Paz Flores).

Benjamin Flores’s father-in-law, Francisco Pinto, was an office-worker at the Secretary of Government (MINAS GERAIS, 1896). As such, he would be entitled to a house in the new capital, Belo Horizonte. With his passing in 1897, the right to have a house was transferred to his wife, who was able to receive the mortgage from September 1898 (MINAS GERAIS, 1898, Apr. 7).

Benjamin Flores, too, saw himself dealing with questions of housing from 1897. Unlike his mother-in-law, he demanded from the city government the rent of “[...] one of the old houses in Bello Horizonte” (MINAS GERAIS, 1897, Sep. 22, p. 1). His demand was approved. One may wonder why he wished to rent a house instead of buying it and - which is more interesting - why he preferred an old one. A plausible justification might be his income, which did not allow him to buy a housing property as soon as he moved to the new capital. In fact, already in the first months of 1898 he was in trouble to pay all the rent at once. The Minas Gerais newspaper (1898, Apr. 19) told he had requested to pay the rent twice. His request was not only denied but also replied with the following advice: if the rent was expensive, then Benjamin Flores should search for another house with a cheaper rent.

Benjamin Flores took the advice. In February 1899, he was trying to rent another house, of “type 6, on Alfenas Street” (MINAS GERAIS, 1899, Feb. 28, p. 1). On Alfenas and Grão Mogol streets, the government aimed to build popular houses in an attempt to diminish an imminent problem: “[...] housing deficit, especially for workers”; after all, in December 1897, the capital had only “500 houses (200 of civil servants)” and urban services such as “electric lighting, water supply,” while the population amounted to 12,000 inhabitants. In August, Benjamin Flores already intended to buy a government’s house. He demanded the creation of a law that allowed the government to sell him a house coherent with the same legal conditions for civil servants to acquire real estate. He had paid a certain amount of money in advance construction firm (Alberto Bressane & Co., who built popular houses at Alfenas Street) and wanted to negotiate it with the government (MINAS GERAIS, 1899, Aug. 15). The request was refused.

In September 1899, Benjamin Flores still lived in the type-6 house but was unhappy. Among “other residents”, he was facing difficulties and demanded a “[...] lowering in the rent price of type-6 houses in which they lived.” Again, he had a request denied by the government (MINAS GERAIS, 1899, Sep. 20). In addition to the high-priced rent, sanitary conditions were poor, so that late October Benjamin Flores required the building of a latrine in the house where he lived (MINAS GERAIS, 1899, Oct. 21). The newspaper note on his requirement informed of other problems that give a clue of the sanitary problem they have to face. It was lacking not only sewage but also running clean water, because other residents made demand of connection of the water supply network with their houses.

As one may infer from these facts, housing conditions were difficult. The lack of running water and sanitary sewage networks gives a clue of the context of living: a planned city in full process of building, urbanization and territorial expansion (with the selling of lots in new areas as well as the building of residential neighborhoods for the working class). Such conditions may have led Benjamin Flores to the limits of tolerance, since in December 1899 he presented the design of a house he intended to build up “in a suburban lot” (MINAS GERAIS, 1899, Dec. 4, p. 1). His requirement had full approval (authorization). At the same time, he acquired the house where he lived in at Villa Bressane neighborhood, since he had requested more time to pay for it, as told by Minas Gerais (1900, Feb. 17). Besides buying the house, he applied for the purchase of “urban” and “suburban” lots between 1898 and 1899 (see Minas Gerais, 1898, ed. 88, 295 and 311; 1899, ed. 149, 236 and 246).

The real estate business of Benjamin Flores merit some thought, especially when it comes to his financial resources to buy real estate. After all, in July 1898, his first son, José Flores, was born; in addition, he may have had extra expenses with the law school, for in 1897 he had already done all the paperwork required to get enrolled (MINAS GERAIS, 1897, ed. 85). In February 1898, he still worked as amanuensis at the Secretary of the Interior - and was subject to have his salary with a decrease due to oversight at the Secretary of Finance, as it reads a note on the reimbursement ascribed to him published in the Minas Gerais newspaper (1898, Sep. 20).

The possibility of a second job (and of more income) as a teacher he would have only in July 1898, when it was created the Ateneu Mineiro school, aimed at students interested in higher education. Benjamin Flores was the school head secretary and took care of the relationship with the press (and the local society as well). In addition, he took over the role of teacher (MINAS GERAIS, 1898, July 11). Thus, it may be that he had derived extra income from his involvement with this venture and felt sure enough about buying real estate (lots).

It may be as well that the purchase of a lot was accessible to the working class: construction workers, traders and civil servants, among others. In fact, the acquisition of lot in the newly inaugurated capital, even in areas that already had urbanization services (electrical lighting and water supply), had a facilitator, which is the land low pricing in the first ten years of the city. The decision of Belo Horizonte’s first mayor of “extinguishing agglomerates of shacks (casebres)” in Alto da Estação and Leitão neighborhoods (nowadays Santa Tereza and Barro Preto, respectively) demanded to sell many lots “[...] for workers at the ratio of 20 réis the square meter”. Lately, there was a new offering of lots for sale aimed at civil servants at the price of 5,000 réis a unit. In addition, residents of Ouro Preto who owned real estate in the new capital felt harmed by tax charging over buildings they owned in certain areas. This devaluated their properties, even with the compensation they had right to gain, which was a suburban lot. The incipiency of commercial business and the almost inexistence of industries led them to sell their lots at low prices. Besides, private individuals and civil servants could buy “contiguous lots, being one free and the other paid monthly”; but they had a deadline “to be occupied” (MATOS, 1992, p. 8).

These observations give a clue of how Benjamin managed to invest in lots Flores being a civil servant and teacher dependent on wages. Purchasing conditions such as monthly payments favored the acquisition for a population that soon became larger and larger. It refers to those who moved to the new capital aiming to work in its construction. To a workforce of “low levels of qualification”, the state had to finance facilities as hostels, for - as one may infer - it was “[...] insufficient the number of housing and collective lodgings.” Workers, of course, reacted by building what was possible to them: cafuás (a hut made of earth clods and straw roof) and “shacks”; while the city government was building “wattle-and-daub houses roofed with zinc leaves” to be “rented at modest prices” by married workers and their families as well as by singles (MATOS, 1992, p. 9).

Given the housing shortage growing (affecting severely the working class), the government recurred to other strategies: “[…] the construction of popular houses in Grão Mogol and Alfenas streets (100 units) [was] negotiated with private individuals […]” as well as formal granting of advantages to stimulate civil construction. An example of advantage was the decrease in taxes over “[...] buildings of the same owner aimed at housing and not exceeding a certain annual value in the rent charging” (MATOS, 1992, p. 9).

The political agent: elections and candidacies

In a context of precarious housing conditions for the working class and of government measures to improve them, Benjamin Flores reacted to it. In 1911, as member of Belo Horizonte’s advisory board, he submitted proposals for legal changes aiming to solve the housing shortage problem. His intentions included:

[...] to turn workers into owners so that we may have the permanent arms our industries need. We want the newly contracted employees to have a ceiling to avoid being overtaken by renting, which is absorbing 50% of their salaries. Finally, we aim to build neighborhoods to eliminate the infectious and anti-hygienic cafuas and tenements (cortiços) (FLORES, 1911, p. 2).

These ideas stemmed from someone who knew well workers housing conditions: it lacked sewage and clean water. Not by chance, infant mortality stood out (MATOS, 1992).

In 1899, Benjamin Flores became a teacher at the Ginásio Mineiro school in Belo Horizonte, an occupation that was perhaps incompatible with his job as amanuensis but a more remunerative one. Not to mention that he became more known in a society that was being established. In 1898, the year he was approved in the public contest to become Latin teacher at Ginásio Mineiro, his facet of citizen aware of social problems such as working class housing conditions began to appear in the press. Stories referred to visits he paid to Minas Gerais government, as he did in 1898 along with military staff and senators (MINAS GERAIS, 1898, Sep. 20); to meetings he had with people from business environment, as when he accompanied a mining entrepreneur to evaluate manganese deposits in the urban area of the capital (DIÁRIO DE MINAS, 1898, May 14). As a member of the city advisory board, he managed to be known by authorities of higher position in the political hierarchy as Fidélis Reis, a congressman who worked on behalf of vocational education in Minas Gerais. In 1912, Benjamin Flores joined a group of Belo Horizonte politicians who went to Rio de Janeiro to meet Brazil’s president (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1916, Jan. 29).

Politics drew Benjamin Flores interest and efforts as much as education did. It is as if he had seen in the political activity a more feasible possibility to show and develop projects aimed at improving working class living conditions as well as conditions of life in the city as a whole; and to develop industry and commerce business, among others. Such impression is justified, for example, by the mention of his name as candidate for Minas Gerais Congress in March 1903 (O PHAROL, 1903, Mar. 14) and, in the following month, as a member of a board formed to recount votes due to a contestation of election results (JORNAL DO BRASIL, 1903, Apr. 4). Once Benjamin Flores was unsuccessful in the poll for senator, it remained to him to try to the election for alderman in 1907. This time he won. In fact, there was a preference for candidates who were teachers (JORNAL DO BRASIL, 1907, Nov. 2).

Nevertheless, that preference for teachers as candidates to occupy the town hall as alderman had no positive effect on the voting for congressman. In 1909, the result of the poll in Belo Horizonte urban districts showed how low Benjamin Flores popularity was. He had 723 votes, while the most voted candidate obtained 7,429 (O PHAROL, 1909, Mar. 14). With the defeat in the first district, he aligned himself as a candidate for the fifth district. He was among the residents of this voting region who searched to improve it. Positive attributes ascribed to him included to be a “distinguished teacher”, to be a “well-related person” and “to have solid elements in his favor, capable of elect him, even being out of the party selection” (O PHAROL, 1903, Mar. 14, p. 1). Again, he lost the poll; besides, he did not get enough votes to elect himself as congressman in 1915 - still fifth district candidate (O PAIZ, 1915, Feb. 2) - and as senator, in the election of 1927 (A TRIBUNA, 1927, Mar. 13).

These failures allow seeing Benjamin Flores as an unpopular politician. His terms of office did not go beyond the ones at the town hall. Therefore, it is not surprising that he had been considered as likely to give place to another candidate in the fifth district candidate selection the party defined in 1912 (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1909, May 14). In addition, some saw him as an advocate of his own causes. As one reads in newspapers, his image was that of an “[...] efficient alderman that crammed the annual city budget with amendments related to personal favors that, fortunately, never achieved approval” (O PAIZ, 1915, Feb. 17, p. 6). There were those who saw professors (teachers as well) with no background for politics, that is why they considered to change politics in Minas Gerais.

The public agent: city advisor

In addition to his attempts at being elected and to the polls he won regarding political positions in Belo Horizonte town hall and Minas Gerais congress, Benjamin Flores was elected to a vacancy in the city advisory board; and it was as such that he managed to propose projects. In 1909, his actions stood out when he declared and justified, in an open letter, his adherence to the supporters of Hermes da Fonseca, then running for president. His attitude meant the city advisory board would have no representative in the National Convention to launch Rui Barbosa’s candidacy. The open letter would have been quite commented (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1909, Apr. 29). Also controversial was Benjamin Flores proposal of amending the city budget to include payment for city advisors. The O Pharol (1912, Oct. 5) newspaper referred to rumors on the proposal being criticized and surely refuted by the congress.

Benjamin Flores’ proposals as a city advisory were not always welcomed. In some cases, the repercussion they caused in the press obliged him to justify them. One of his justifications was written to his project of enlarging Afonso Pena avenue to make room for “private constructions”. It was sent to a newspaper in Belo Horizonte - the Estado de Minas - and reprinted by O Paiz newspaper from Rio de Janeiro (which has a branch in Minas Gerais capital). O Paiz called it “disastrous”. The critical point was that the enlargement process would take “a wide strip” of the city park (O PAIZ, 1913, Feb. 11, p. 5).

Despite the criticism to certain Benjamin Flores projects presented to the advisory board, one notes continuity in his social ideals and the attention he devoted to the demands of Belo Horizonte society. In 1912, he showed a project concerning the creation of a city hygiene board to take care of public health. Such care would focus, among other points, on the overseeing and control of food and on visits to “private and collectives” housing (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1912, Sep. 17, p. 12). As a type of contrast with conditions of health and hygiene in areas where infant mortality reached high rates, Benjamin Flores saw his project undergo the ideals and eugenic prescriptions that permeated discourses and actions of public authorities and medics of Belo Horizonte. Such undergoing was clear in an amendment to the project including the annual organization of a “robustness contest among one-year-old children”, so that the “[…] first ten ranked children would receive money sums as prize” (CORREIO PAULISTANO, 1913, Oct. 6, p. 4).

The ideas Benjamin Flores presented in 1911 aiming to solve the housing problem echoed in his term of office in the city advisory board. In 1914, it was showed to be assessed his proposal of granting “[...] support to industrial and commercial companies and owners of factories and shops regarding the building of houses for workers.” Besides urban housing, the forms of urban locomotion were a concern for Benjamin Flores, so that he proposed to the advisory to demand the “[...] building of two suburban train lines, with cheaper tickets, between this city [Belo Horizonte] and the city of Santa Luzia do Rio das Velhas” (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1914, Oct. 3, p. 2). The idea was to replicate something that already occurred between the capital and Sabará city. There would be a morning train and an evening one (O PAIZ, 1914, Oct. 4).

Benjamin Flores recognized the institutional representations as an important step for the “progress of the municipality” and presented a bill for that (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1912, Sep. 17, p. 2). In addition to stimulating the formation of associations of class and professional, he found himself in the condition of participating in some of them. His stimulus reverberated in the creation of Barro Preto neighborhood association, where a relevant part of the working class lived; not by chance, he would become its “president of honor” (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1916, Nov. 4, p. 7). That is why Benjamin Flores was seen as a defender of the working class needs. He was even invited to represent the Confederation of Workers of Minas Gerais in a national congress. Besides, he seems to have assimilated the role of adviser and supervisor as part of his personality. Benjamin Flores was already a member of the advisory board of Belo Horizonte’s labor center (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1912, Oct. 24) when turned out to be a member of the supervisory board of an association for the family support, in which he used to approve accounts alongside other members (O PAIZ, 1913, Aug. 3). It is curious, however, that Benjamin Flores, a teacher and an active public agent, has worked to form a teacher’s association only almost thirty years after his early days of teaching. After all, his efforts on behalf of such association date back to 1928, with a meeting of teachers to approve the statutes (CORREIO DA MANHÃ, 1928, June 16).

The reach of Benjamin Flores’ projects in the city advisory board extended to the economy. He bore farmers in mind in proposing a bill that would prescribe an annual fair for the showing and selling of farming output (O PAIZ, 1912, Oct. 5). Commercial business was a worry for Benjamin Flores as well. He acknowledged that the capital had become “the largest commercial and industrial center” of the state, as it gathered more than “600 commercial and fifty houses and eight different factories” (O PAIZ, 1916, Feb. 17, p. 2). For this, it would be useful to open a branch of Bank of Brazil. In name of such project, he published an article in the O Paiz newspaper pointing the already approved opening of the branch.

While acting as a public agent, proposing projects for Belo Horizonte, Benjamin Flores acted as an educational agent proposing measures and developing projects in the field of education. One of his projects was to create schools.

The educational agent: teacher, teaching advisor and school owner

It is important to remember that from 1899 onwards, Benjamin Flores took Latin teaching classes at the Ginásio Mineiro school as his main professional activity. He, however, did not restrict his performance to classrooms. In 1905, he became member of a high council for public education, whose president was Minas Gerais’ secretary of the Interior, Delfim Moreira (O PHAROL, 1905, June 16). Such position allowed Benjamin Flores working in the field of inspection, so that the Ministry of Justice and Interior Affairs pointed him out as overseer of exams in schools as Itajubá city’s Ginásio de Itajubá (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1916, Dec. 3, p. 7). The following year, he was “commissioned by the federal government” to evaluate the Academia do Commercio school and write a report of his judgments on the subject (A UNIÃO, 1917, Nov. 10, p. 1).

Benjamin Flores’s work at the Ginásio Mineiro was beyond teaching. Three years after being created, such school was on the verge of stopping its activities because the number of enrollments did not justify its maintenance. Therefore, a group of teachers, including Benjamin Flores, arranged a meeting with the rector to outline solutions to the problem motivating the possibility of closure (O PAIZ, 1912, Aug. 15).

Even as teacher at the Ginásio Mineiro and as advisor in the city advisory board, Benjamin Flores managed to create conditions and have time not only for the teaching in other schools, but also to the foundation of schools. In 1912, he created the Escola do Commercio school, in association with two more people, one of them being a congressman (O PHAROL, 1912 Aug. 15). In a certain sense, this initiative converged to his efforts as adviser to promote commercial business. Two years later, he joined others to create the School of Agronomy and Veterinary (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, 1914, Aug. 11). It is possible that this school had faced financial hardships because Benjamin Flores, as one of its professors, presented to the city advisory board a project referring to financial aid to the school (DIARIO DE PERNAMBUCO, 1815 Feb. 1st).

Benjamin Flores’s most enduring initiative was his Escola Profissional Feminina school, aimed at offering young women professional training in varied fields. He showed his interest in such modality of education in 1909. By means of his indication as city adviser, the city advisory board sent a message of “applause and congratulation” to the president of Brazil because of the decree he signed authorizing “[...] the creation of vocational schools in all capitals” (CORREIO PAULISTANO, 1909, Oct. 10, p. 2). Benjamin Flores’ indication gives a clue of his motives to attend the congress on vocational education in 1911.

There are doubts about the foundation year of the Escola Profissional Feminina. There is what tells us Barreto (1950, p. 217): “[...] in 1913 teacher Benjamin Flores founded the Escola Profissional Feminina school.” There is a mention to it in a São Paulo’s newspaper article dated March 12, 1913 (CORREIO PAULISTANO, 1912, Mar. 12, p. 3). There is the Belo Horizonte yearbook (BELO HORIZONTE, 1953, p. 151), which repeats Barreto: “in 1913 teacher Benjamin Flores founded the Escola Profissional Feminina school.” Finally, there are the Ministry of Agriculture reports presented to the president of Brazil by the minister of State for Agriculture, Industry and Commerce, Miguel Calmon du Pin e Almeida (1925, p. 640), which tells us that the “Escola Profissional de Bello Horizonte [was] founded in 1917.” Gomes and Chamon (2010) say it is probable that Benjamin Flores has considered as the school founding year that one in which its certification was recognized by Minas Gerais government, which was in 1920. The previous period (1913-9) would be disregarded as part of the school’s historical time because it was not part of the “official” calendar. “Thus 1919 would be the official beginning of the school and the previous years - perhaps uncertain years, moved by the structuring of the school - would be relegated to oblivion” (p. 11). Given the up-to-now lack of more records on the early days of such school, these authors’ hypothesis seems plausible enough. A 1920 issue of the Minas Geraes newspaper informs that the school was

[...] founded in August 1919, as it is published by the Minas Gerais newspaper dated the month and year [...] as an institution of technical and professional training, with an indefinite lasting, which has the aim of preparing its female students with solid knowledge of an art or a profession, so that to turn them in the struggle for life useful to themselves and to the nation (MINAS GERAES, 1920, Jan. 23, p. 4).

Date uncertainties aside, it is clear the dynamics of Benjamin Flores life as a public and educational agent, not to mention his other increasing and numerous activities such as taking part in associations, overseeing exams and taking care of his increasing family. That is why it is amazing his ability to manage everyday life dealings, for he used to transit through different contexts not only of his private and public life but also of a school with such a bold purpose as to turn women into professionals as part of a modernization movement and of efforts to the country progress.

Benjamin Flores’ ideal of education for women echoed in the life trajectory of a former student of his school, Maria Celme Caetano. The daughter of a mother who had leprosy, she used to be “invited” to leave schools where she was enrolled as soon as the headmaster found that her mother suffered from such disease. She was part of a group of people excluded from certain social settings and subjected to “means driven by society” to “categorize people” (GOFFMAN, 1975, p. 73). She was stigmatized because she had “[...] attributes considered as common and natural for members [...]” of any categories, such as people suffering from leprosy. In the 1930s, this mentality of intolerance translated into “[...] the belief that it was necessary to isolate, ban, exclude and marginalize patients [...] [into the] compulsory isolation as the only prophylactic measure able to refrain the growth of leprosy in Brazil” (SILVA, 2009, p. 70).

Benjamin Flores’ school was among the few ones - not to say the only one - to accept Maria Celme as a regular student who would win her professional teacher certificate in 1946. Here is how she told her student experience at Benjamin Flores’ school for women:

I was put in another school: “Escola Profissional Feminina” on Amazonas avenue, on the corner of Tamoios street, owned by the teacher: Benjamin Flores. This latter was a spiritist and his classes focused on languages: Tupi Guarani, Greek and Latin. Scheduled to take place every day, they were only to make students remain in class and in silence. There was no intention of them being taught. Professor Flores himself was the lecturer. He talked all the time about the tongues. He was very old (CAETANO, 2011, p. 35).

Despite the judgmental tone in the former student diction as to Benjamin Flores language classes - a “very old” teacher, she said -, one must say his work in the school extended to various activities: it included school management, teaching, and paperwork.

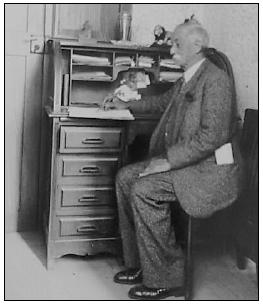

Source: family archives of Tereza Cristina Flores Moura (unknown photographer)

Figure 2: Benjamin Flores at the working office in his school for women

He took care of forms aimed presenting exams results to Minas Gerais government. When it was not him the writer of such documents - as it happens to applications sent to the state -, he was the one to revise their content and validate them by signing and recognizing the fidelity between, for instance, a typed document and the handwritten original. His revision was thorough, as one may see in the correction he made in an excerpt of a typed document, which is a report submitted to the “secretary of Security” of Minas Gerais (FIG. 2).

In the fifth line, Benjamin Flores made an amendment to correct a change of a verb: instead of the word “comeram” (meaning “they eat”), it should be typed “começaram” (“they begun”). As Benjamin Flores signed it, the document was probably forwarded with his handwritten correction to save paper and extra work.

Source: Public Archives of Minas Gerais

Figure 3: Excerpt of a report on Benjamin Flores school for women, Jan. 1930

In 1931, Benjamin Flores retired as teacher at the Ginásio Mineiro school. He was almost 60 years old (DIÁRIO DA TARDE, 1950, May 12). After retiring, as one may infer from historical sources, he devoted his full time to his school for women.

The man: the grief for the death of Benjamin Flores

In May 1950, Benjamin Flores passed away. The event of his death was commented with regret by the press in Minas Gerais, including especial mentions to his teaching work. Among other newspapers, the Diário de Minas published an article on his death in the issue of May 12:

The news on the teacher Benjamin Flores’ death yesterday in the capital reflected intensely in the various social circles of the capital and in the country cities. Son of a traditional family of Minas Gerais, he came to be the head of another large and dignified one, whose sons and daughters are rooted in Minas Gerais in various sectors. A constant thing in the life of the master that Minas Gerais has just lost was the commitment to the teaching profession. That is why he dedicated himself to the new generations his love of culture and his righteous personality. From an early age, he devoted himself to the teaching and school activities feverishly, to the point of leaving the medical school to focus on the teaching work. With his intelligence and efforts, he would found numerous schools and manage other ones, namely Externato Ouro Pretano, in Ouro Preto city; Ateneu Mineiro, in this capital, Escola do Comercio of Belo Horizonte; Escola de Agronomia e Veterinaria in this capital; Escola Profissional Feminina of Belo Horizonte, still managed by him. [...] A widely known character in our educational environments and society, he was a well-esteemed person due to his human qualities, allied to great intelligence and culture. His life is deeply linked to the development of school teaching in Minas Gerais, as it prove his biographical notes, which give an idea of his long and fruitful works (DIÁRIO DE MINAS, 1950, May 12).

An article published in the Minas Gerais newspaper by a certain José Clemente gives a clue of how Benjamin Flores was in the everyday life of his public affairs and dealings as well as of his importance to Belo Horizonte. In his words,

Belo Horizonte is running out of its traditional characters. It is inevitable such loss. Now, it dies teacher Benjamin Flores. He had his life linked to the capital and its people. As teacher, he has been very close to generations of young people. As city legislator, he was in direct touch with the population who elected him subsequently to the city advisory board, so that he would work for their interests when the people representative had to sacrifice the time of his everyday life duties to serve the city without any remuneration. Benjamin Flores has always been a busy man. He worked ceaselessly. Nevertheless, he ran to the city advisory board, offering himself to serve the city, which owes him a lot. He encouraged major enterprises, especially in the cultural and educational spheres. [...] Benjamin Flores saw, through the future, the need for the capital to have an establishment of that nature as an instrument of social cooperation. He put all his efforts and energies in the school for women, which went through difficult moments but triumphed not only as a teaching establishment but also as one of the key solutions to social problems by recognizing the valuable work capacity of young women in Minas Gerais. He educated the youth, served his people, and worked for his city. He did so without complaining of fatigue, during an existence of almost 80 years. And to die poor! We never saw him stopped. On the street, always in a hurry, hands full of wrappers. He would not stop, to avoid missing the time of his duties. [...] [He] was the personification of an original fighter, one that no longer exists (CLEMENTE, 1950).

The importance of Benjamin Flores stood out among Minas Gerais congressmen such as Julio de Carvalho, who requested an official condolence message to Benjamin Flores family. Such request highlighted the recognition of his work on behalf of Belo Horizonte society. Several members of different parties spoke. Lima Guimarães, who had been Benjamin Flores’ student, expressed his feelings with these words:

He was my master in the days of the Ginásio [Mineiro school]. I know his devotion to teaching, because he had his whole life dedicated to the improvement of youth, and even after growing old, after a fair retirement for his relevant services to the education in the state, his forever-young spirit was still devoted to the teaching of youth. This is why he founded the Escola Profissional Feminina [...] With the passing of teacher Benjamin Flores, the public teaching lost one of its elements of relief and Minas Gerais one of its greatest teachers. By P. T. B. [party]; I associate myself with the homage this house pays to the memory of teacher Benjamin Flores (DIARIO DA ASSEMBLEIA, 1950 May 13).

The congressman Juarez de Souza Carmo spoke of his reaction to the death as it follows:

The homage Minas Gerais congress paid to the memory of teacher Benjamin Flores is surely the fairest and the most deserved one. Teacher Benjamin Flores dedicated all his life to teaching, thus providing immense service to our state. [...] With a whole life devoted to the most noble of causes, he deserved it [the homage]. Therefore, it is with deepest regret that members of the Republican Party, on behalf of which I speak, received the truly sad news of his passing and states its solidarity with the homage this house pays to his unforgettable memory (DIARIO DA ASSEMBLEIA, 1950, May 13).

Speeches highlighted Benjamin Flores teaching work more than his concerns over working class, children and woman. Nevertheless, his handwritten list of last whishes seems to contrast with the homage paid on behalf of his memory (to which death tends to lead). He handwrote the list in the imminence of death.

Last wish - 1st A third class burial. 2nd No invitation in the press, on the radio, in vitrinas and personally. 3rd No mourning. It means nothing. 4th No mass of 7th and 30th days. If they celebrate it, then no invitation in the press. 5th Do not provide information on me to the press. 6th If the government want, as a homage, to put my name in some school or street, forward a letter on behalf of the deceased refusing it, for in life, despite all services provided, he did not deserve any consideration of state authorities.

As it reads, the sixth request has a certain tone of disappointment as to the state: to the lack of public recognition of his work in life. Benjamin Flores was incisive: he refused posthumous recognition by the state and the city government. Given his efforts in a school and teaching project that was not necessarily for the future, perhaps he may have expected more than what he got from the state. Benjamin Flores glimpsed a goal to fulfill with his school for women in the very present of this latter and of the needs of his founder and manager. He did so in the very present of a planned city in process of establishing itself as a model of modern city for the country

Final remarks

The understanding this study aimed to build focuses on the historical and social antecedents and personal attributes of Benjamin Flores in Belo Horizonte to carry out his schooling and teaching project; which means the foundation and maintenance of a school for women and an educational program aimed at turning them into professionals. Also sensitive to the modernization process in Minas Gerais, other men spoke in favor of such education for women in the new capital of Minas Gerais. It was Benjamin Flores, however, who took practical measures, who went from the discourse to the concrete action.

The historical understanding intended with this study allows saying the opening of a school for women to train them in certain professions was the culmination of a process of apprehending a social reality in formation process; the culmination of a process of leaning on Belo Horizonte society demands, especially the working population’s, who crowded the city precisely to build it. This is why Benjamin Flores grew concerned with housing conditions, family and children assistance, as well as with the encouragement of the working class as to form institutional organizations such as associations and the likes. His actions to reach his goals were noticeable in his work at the city advisory board and - it is probable - at the town hall as alderman. At the same time, his teaching work seems to have been a way to conceive alternatives to meet other demands of the population he knew well.

In fact, in opening his schools, Benjamin Flores seems to have glimpsed ways to broaden his role as public agent. His first initiative in this sense turned to the education aimed at commercial business, for he saw this economy sector developing quickly in Belo Horizonte. Above all, he saw the industry sector as a working place for women; and it is precisely in this domain that his actions stood out. In a certain sense, as a man very aware of his own time and space, Benjamin Flores understood that offering other possibilities of professional development for women in the public sphere was, in fact, making the new capital of Minas Gerais the symbol of the urban modernization of the country. Belo Horizonte could not be a model city for the Brazilian republic if its female population stayed in the condition of submission and restriction to the private sphere, if women did not integrate the Republic.

Founded to turn women into trained professionals of education and other fields, Benjamin Flores school, which he struggled to keep operating, created conditions for women to be part of the public sphere as well. It did so by providing them with skills not only to perform jobs such as teachers, secretaries, clothing designers, florists, seamstress but also to handle machines in the garment and weaving industry. Benjamin Flores school was a way to offer women professional training that placed them in he city as competent workforce to play roles and hold professional positions that tended to be marked by a masculine workforce.

texto en

texto en