1. The national circus school and the production of knowledge

This paper sought to analyze the context of the creation of the National School of Circus (ENC) in Brazil in 1982, based on the relations with the Brazilian State and the education and culture policies of the period of the civil-military dictatorship. The ENC began to be discussed in the Ministry of Education and Culture in 1977 and was inaugurated in 1982, being the only institution of formation of circus artists in full operation maintained by the National Arts Foundation (FUNARTE).

The first academic productions about the circus in Brazil date from the decade of 1970/80. This is also the period of implementation of our first circus schools. The Piolin Academy of Circus Arts, a state institution, was founded in São Paulo in 1978, but in 1983 had already closed its doors (SILVA E.; ABREU, 2009). In the following years the ENC was created by the Federal Government (1982, Rio de Janeiro), the Circo Escola Picadeiro (São Paulo, 1984) and the Escola Picolino de Circo (Salvador, 1985) (Ibidem). This movement has expanded considerably and, today, Brazil has hundreds of circus schools, diversifying the spaces occupied by this artistic manifestation, and the people who attend, but also perform circus practices.

In a survey conducted in 2012, we found 77 postgraduate studies, among master's theses, doctoral theses and free-faculty that addressed the circus (KRONBAUER; NASCIMENTO, 2013). By updating this information with data obtained this year, from the database of the Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (BDTD), we found another 49 graduate studies on the circus produced between the years of 2012 and 2019. Among these 126 works, we can highlight specific study objects such as the history of the circus (36), the art of the clown (25) and the circus-theater (24). When we looked at circus schools and the training of the circus artist, we found 16 works, of which four have a certain approximation with the ENC.

Rodrigo Matheus' dissertation (2016) presents elements of the creation of the Piolin Academy of Circus Arts and the Circo Escola Picadeiro, in the state of São Paulo. Both institutions were founded in the same period of the ENC, seeking to meet similar objectives. The thesis of Rodrigo Duprat (2014) addresses the processes of formation of circus artists today, going through a brief historical reading of the creation of the first circus schools in Brazil.

However, only our doctoral thesis defended in 2016 (KRONBAUER, 2016), and a master's dissertation were specifically concerned with the ENC, object of this research. Part of the thesis results will be discussed in this article. The dissertation, written by Rosa Maria Ramos, consisted of a brief description of the foundation of the school, and sought to pay more attention to the curriculum organization, its physical structure, the profile of students, the teaching staff, among others, during the period of the research (RAMOS, 2003).

In order to contribute to the production of knowledge about the circus and its history, but also about human societies as protagonists and fruit of this history, we start from the conception that the social organization in different times and spaces is based on the relationships that we establish in the modes of production of material life (MARX AND ENGELS, 2007). The human being becomes human from the transformation of nature to produce its existence - work - and this process is dialectical: nature offers conditions for the production of material life and the human being transforms it with his work; nature becomes a product of work, while the human being itself is transformed, thus constituting a social reality (NETTO, 2011). There is a "double determination of an unsurpassable natural base and an uninterrupted social transformation of this base" (LUKÁCS, 2012, p. 285). Therefore, the relationships that will be guided in the text are not cause-effect, but processes in constant motion, which involve multiple constraints.

In Brazil, the Modern Circus, or Traditional Circus, has become an important cultural and entertainment diffuser of much of the population in cities and countryside, between the elite and the periphery. The circus had in the family one of its essential institutional values (COSTA, 1999). The child symbolized the certainty of continuity and, therefore, the concern with his education and artistic training was central to all members of a company - they taught how to be an artist, but also taught the necessary knowledge to live in the circus (SILVA E, 1996). The formation of the artist took place in the daily life of small troupes and large companies, concomitant with the formation for life. In this context, the show was the result of the construction of the lives of the women, men and children who made the circus, in constant learning process. However, it seems that, at a certain moment, intergenerational relations no longer met the need for the formation of artists and did not guarantee the survival of the circus.

The discourse on "the crisis of the circus" was recurrent in the speeches of circuses. Among the factors listed by Rodrigo Matheus (2016), we can mention: the devaluation of the circus and the lack of recognition as a professional category, which discouraged many circus dwellers from remaining in the circus; the expansion of the mass media, especially television, which provided cheap entertainment without the need to leave the house; the replacement of railroad transportation by investments in the highway network and in the automobile industry in Brazil, starting in the middle of the 20th century, which made itineracy more expensive for the company, and more autonomous for the artist (possibility of acquiring a car), weakening the bonds; and the search for formal education, which took many children out of the circus, interrupting the continuity processes. In this scenario, a circus school seemed to be part of the answer to the wishes of circuses.

In addition, in many biographies, reports and newspaper pages of the time, we noticed a certain rapprochement between the circus institution and the Brazilian State. Politicians attended the shows, people of circus origin occupied positions and spaces for discussion in the government, influential artists of the most diverse activities sought in the circus elements for their art and proposed policies of integration. Finally, a favorable scenario was established for the Federal Government to support the creation of a circus school in Brazil. Maybe they were not exactly actions that reached the necessary dimension to consolidate the circus as an artistic manifestation from the perspective of theater or dance, but, for the first time, there was some attention on the part of the government.

However, this approach was by no means disinterested. On the contrary, this text will bring elements for us to understand how the arts, and especially the circus, were configured as an instrument for the formation of the new Brazilian man who was desired for the end of the 20th century. It is worth mentioning that Brazil experienced a unique period in its history: the civil-military dictatorship had Ernesto Geisel in front of it, president whose mission was to prepare the country for political opening and a new phase of development (SILVA V, 2001).

In this sense, we observe that the relationships between circus life, the educational role of culture and the Brazilian State at the end of the 1970s were fundamental to the creation of the ENC - they do not explain the totality, but certainly are part of it. As Kuenzer (1991) points out, the relationship between the productive system and the school is not deterministic, but it is also non-existent; it is dialectical. So are the relations of rapprochement and distance between education, culture, the State, the productive system, the circus and the ENC.

[...]This dialectic is incomprehensible to those who are not capable of placing themselves above that primitive vision of reality, according to which only materiality, and indeed objectively existent, is recognized as something, attributing all the other forms of objectivity (relations, connections, etc.), as well as all the mirrors of reality that immediately present themselves as products of thought (abstractions, etc.) to a supposed autonomous activity of consciousness. (LUKÁCS, 2012, p. 314).

Therefore, this text aims to analyze the relations between the circus, culture as an educational instrument and the Brazilian State of the 1970s and 1980s that conditioned the creation of the ENC, a state institution and the first of its kind in Latin America.

1.1 Methodological Trajectories

The Circus is an art, or a set of artistic manifestations, that is constituted in the social relations of production of existence, in daily life, in the intergenerational coexistence, in the body, in the said language, and not always written. Therefore, for the selection of the sources of this research, it was important to open the possibilities to face the most diverse forms of communication as a potential source, as is the case of interviews, testimonials, reports, literary and biographical works, among others. As Tonet states: "[...] will be the objective reality (the object), in its own way of being, which will indicate which should be the methodological procedures.". (TONET, 2013, p. 112).

Therefore, we interviewed important characters for the history of the ENC, among which we highlight its founders: Luiz Olimecha (circus) and Orlando Miranda (president of the National Institute of performing arts- INACEN). The interviews and the disclosure of the interviewees' identities were conducted with their consent. These are semi-structured interviews (MINAYO, DESLANDES AND GOMES, 2010) in which, initially, we asked the participants to talk freely about their life in the circus and about their relationship with the school. From the stories reported, we directed specific questions about the organization of work when they were artists, and about the process of creation of the ENC. It is worth considering that the story of each character can be nebulous when told by an unreliable historian whose looks on the same reality can be different, so it requires a careful look of the researcher and dialogue with other sources. Thus, under these precautions, its contribution is essential for the understanding of the total process, because it allows knowing the universal and the different forms it takes in the singularities of each individual (HOBSBAWM, 2012).

In the CEDOC of FUNARTE and in the collection of the ENC were found newspaper reports, minutes of meetings, projects for the construction of the school, regulations, curricula of teachers, list of enrollments, among others, and several photographs. We also had access to the photographs of Orlando Miranda's personal collection and to a video with the first public exhibition held by students of the first class of the course of Initiation to the Circus Arts of ENC, the personal collection of Edson Pereira da Silva, student of this first class and, currently, ENC teacher. For the primary sources, we established the period between 1975 and 1984, which corresponds to the year of approval of the National Culture Policy (PNC, BRAZIL, 1975), and the year in which the first group of students from ENC concluded the initiation course in circus arts, respectively. However, to understand the process from this period on, it will be necessary to expand the discussions to the history of the circus in Brazil, and how it was consolidated as an important vehicle for the dissemination of Brazilian popular art and culture.

2. The circuses of the many Brazil...

The Modern Circus inaugurated by the knight Philip Astley, in 18th century Europe, brought the centrality of the relationship between circus and theatre, integrating the pantomime and equestrian art with the circus language of acrobats, jumps, funambulums, prestidigitators and other artists (TORRES, 1998; BOLOGNESI, 2009). In Brazil, the circus language already wandered through dance and theatre performances in the 17th century, but it was with the installation of the first companies in the 19th century, strongly influenced by the European movement, that the circus became Circus.

The circus shows, contrary to what happened in the theater, invested in entertainment, in surprising the audience with elements hitherto inconceivable. Not only were their gestural elements disturbing, but also their family organization that welcomed everyone in bonds of solidarity that surpassed those of blood; the enchantment of the uncertain that unstructured

families; the expenditure of energy that did not generate useful work; none of this was consistent with the stability of the new order that was intended to establish in the country: "There, this could abandon or loosen the behavior required of ladies and gentlemen civilized educated" (DUARTE, 1993, p. 241).

Despite the strong criticism of a so-called "impoverishment" of the performing arts, the circus became a potential agent of democratization of art, because its plurality and, mainly, its itinerancy enabled the different social groups to have access to music, theater, literature, dance, and the performing arts in general, in the most distant places of the national territory

One cannot study the history of the theater, music, record industry, cinema and popular festivals in Brazil without considering that the circus was one of the important vehicles for the promotion, divulgation and diffusion of the most varied cultural enterprises. [...] They divulged and mixed the various musical rhythms and theatrical texts, establishing a continuous cultural transit from the capitals to the interior and vice-versa. (SILVA E ABREU, 2009, p. 48).

In the 20th century the creators of the modernist movement that culminated in the Week of Modern Art, in 1922, were deep admirers of the circus, where they were constantly meeting (COSTA, 1999). The modernist movement would seek in the identity of the Brazilian people, expressed in popular culture, the foundations for the construction of a modern society appropriate to Brazil. Reinforcing the national identity based on popular culture was a way of presenting the Brazilian man as a strong individual capable of, on the one hand, transforming reality and, on the other hand, reproducing it by moving a new industrial productive system that was intended to establish and contribute to the defense of the nation. We refer, firstly, to the concept of culture proposed by Trotsky:

Let us begin by remembering that culture originally meant plowed and cultivated field, as opposed to forest or virgin soil. Culture was opposed to nature, that is, what man had achieved through his efforts contrasted with what he had received from nature. This fundamental antithesis preserves its value today. Culture is everything that was created, built, learned, and conquered by man in the course of his history, unlike what he received from nature, including man's own natural history as an animal species (TROTSKI, 2013, p. 2).

For the author, culture contemplates the human material production expressed by instruments, machines, buildings, etc., from the relationships established between humanity and the concrete material conditions available, that is, "all kinds of knowledge and skills to fight with nature and subjugate it" (Ibid., p. 2).

Culture also makes up the superstructures, the set of methods, skills, customs and values that are developed in the process of producing material life that, meeting the needs of the productive system, condition behaviors appropriate to each era and each society. However, the process of internalization of culture is not something that happens through nature (MÉZAROS, 2008). It is important to assume that the human being learns to be human from the educational processes. We can think of the following relationship: the forms of sociability in different times and spaces are conditioned by the modes of production of material life that make up the cultural framework; through education (formal or informal; intentional or spontaneous; institutionalized or not), this cultural framework is internalized and the forms of sociability are reproduced.

The stage of development of the productive forces has generated, throughout history, groups that occupy different spaces in the social hierarchy, - those who work, and those who live off the work of the other / the owners and non-owners of the means of production / the exploiters and the exploited / the bourgeoisie and the proletariat "[...] because with the division of labor is given the possibility, and even reality, that spiritual and material activities - that enjoyment and labor, production and consumption - fit different individuals [...]" (MARX AND ENGELS, 2007, p. 36). Therefore, there are distinct cultural productions elaborated by and for each of these groups and the possibility of apprehending the antagonisms between a so-called popular culture, and another elitist culture, only occurs in a society of classes (SODRÉ, 1962).

Founded by Sodré (1962, p. 14), for whom "in all situations, people are the set of classes, layers and social groups engaged in the objective solution of the tasks of progressive and revolutionary development in the area in which he lives", Ortiz analyzes popular culture from its aspect of "tradition", or traditional knowledge, or even conservation of a collective memory that unites and identifies the different representatives of people. The author also discusses the approach that is often made between popular culture and folklore, as a production of subaltern classes that seeks in the authenticity of its manifestations the maintenance of reality, without prospects of transformation (ORTIZ, 2003). That is, the search for a national identity in popular culture, when confused with folklore2, could also be understood as a political strategy to hide class antagonisms.

But the modernists brought Brazil as a central element of the arts and perceived in the circus the possibility of a new aesthetic that proposed the appreciation of popular traditions. Alcântara Machado, for example, "knew how to extract from the experiences of the show - theater, cinema, circus - new data to open new paths of prose creation" (LARA, 1987, p. 11). In the same way, Mário de Andrade said: "The only theatrical shows in Brazil that we can still attend are the circus and the magazine. Only in these there is still creation”3.

The famous Piolin4 clown was an interlocutor between the circus and the modernists, considered an example of "brasileirice", with its simplicity and naivety. Such was its representativeness in popular culture and in the circus, that the Day of the Circus is celebrated on March 27, in his honor. For Alcântara Machado "Piolin and Alcebíades5 are clowns, whatever they want, but they are the only national elements with whom our prose theater counts. They should serve as an example, as authors, for colleagues who despise them and ignore them6. Alice Viveiros de Castro, states that the work "O Rei da Vela", written by Oswald de Andrade in 1933 and published in 1937, is a tribute of the writer to Piolin (CASTRO, 2005). The inclusion of two Abelardos (Abelardo I and Abelardo II) as main characters in the story, certainly attests to the presence of Piolin in the imagination of the writer.

Years later, in Brazil in the 1970s, the conception of popular culture, expressed in popular art, among other forms of manifestation, will assume another perspective. The revolutionary romantics of the period of the military dictatorship, of whom Marcelo Ridenti (2014) speaks, would also seek in the culture of the simple man of peasant origin, an alleged identity for the people. Intellectuals such as Ferreira Gullar, Carlos Estevam, among others, will see in popular culture the expression of contradictions and the possibility of becoming aware of the popular masses, the only agents capable of transforming Brazil into a country of equality and social justice, in opposition to the concentration of income and poverty in which the majority of the population lived.

In the same way, the Brazilian State will see in the circus the expression of Brazilianness and, at the same time, an instrument of ideological dissemination, both for its itinerancy and ability to communicate with the popular masses throughout the national territory, and for its content, capable of spectacularizing the values of bourgeois society.

As an expression of these contradictions, the circus seems to have assimilated during the twentieth century important elements that integrated the nationalist ideas of the 1930s, and were again in vogue in the 1970s: national integration - the circus reached the entire national territory; and unity in diversity - the circus synthesized the diverse in the same show. These aspects were of great relevance for the State to turn its eyes to the circus.

3. The enc and the brazilian state of the 1970

The ENC was inaugurated in 1982. However, it was already included in the plans of the Ministry of Education and Culture - MEC since 1977. With Ney Braga, its actions included renewed practices for the area, with PNC-1975, the regulation of the professions of Artist and Technician in Entertainment Shows, the restructuring of MEC and the creation of INACEN. His successor, Rubem Ludwig, gave continuity to the projects by creating the Brazilian Circus Service - SBC, in 1981, and inaugurating the ENC, in 1982.

In addition, the educational policies for the people in the dictatorship were based, to a large extent, on the training of technical personnel to meet the needs of the industrialization process, i.e., education should "train for the performance of certain practical activities" (SAVIANI, 2008, p. 295). It should be noted that, in this case, the technical staff is not restricted to factory workers, but to all the apparatus necessary to reproduce the set of methods, skills, customs and values characteristic of the capitalist system. At the same time, it was up to the universities to prepare the country's leaders (SAVIANI, 2008). The rapprochement between the principles for cultural actions and educational policy was not only ideological, since both occupied the same Ministry.

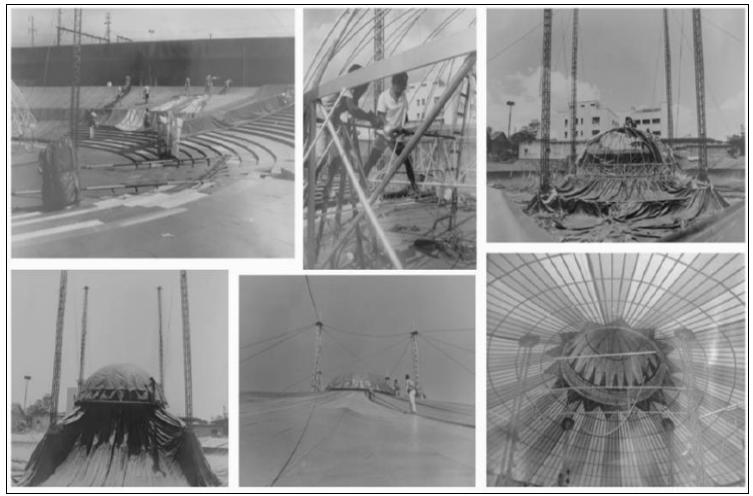

In this context, Orlando Miranda inaugurated the national policy to support the circus, in his management of the National Theater Service - SNT (Figure 1), which included actions such as: diagnosis of the situation of Brazilian circuses and financing of improvements; creation of the Brazilian Circus Service - SBC; and creation of the National Circus and the ENC in Rio de Janeiro.

Source: CEDOC/FUNARTE Collection. Editing by the author.

FIGURE 1 Policy of support to circuses in the Diário do Grande ABC (1978).

Based on the relationships between education, culture and social class, discussed above, we identified some interests of the Brazilian State in supporting and financing the circus, as an instrument of ideological dissemination for the education of new generations, who needed to learn to live in a capitalist, bourgeois society, about to open up again to democracy. At the same time, and contradictorily, this circus in which one invested was also an artistic manifestation of great potential for the recovery of the human universality lost in the work processes and freedoms curtailed during the dictatorship. In Trotsky's words, "Yes, culture was the main instrument of class oppression; but it is also, and only it can be, the instrument of socialist emancipation" (TROTSKI, 2013, p. 6).

3.1 circus receives strong government support7

The approach of the circus to the Brazilian State was nothing new. Since colonial Brazil, the Emperors were deep appreciators of these shows - Orlando Miranda told us that the patriarch of the Olimecha family was professor of Japanese to the Emperor D. Pedro II. However, there are no references about investments or support to the circus institution in another historical moment as there was from the 1970s on.

Ney Braga's statements on the day of the first public exhibition of ENC students, in 1983, reflect the principles that founded the incentive to cultural actions and policies of that period, in the voice of a representative of the State and, at the same time, an admirer and supporter of the arts.

[...] It's not a country of hope, it's a country of certainty. Therefore, in the cultural sector, in the economic sector, nothing slaughters us. Because there are people like you, like you who listen to me. And that is why we are realizing in Brazil the wonder of a spectacle that we have seen today, and so many others, which are certainly worthy of the past, and are building a future of trust, of credit and of a great nation.8

Ney Braga, when Minister of Education and Culture (1974-1978) was a central personality in the elaboration and approval of the national policy of support to circuses, until then non-existent in Brazil. Lucy Geisel, the president's daughter, was another personality whose name is recurrent in sources, and seems to have been an important piece of support for artists. Ruy Bartholo, recognized artist and circus businessman, narrated that one day, in a season in Brasília, in 1975, his show had the illustrious presence of the President's daughter, accompanied by Ney Braga. During the break, Lucy asked Ruy what the government was doing for the circuses and he promptly replied: "Nothing, absolutely nothing" (BARTHOLO, 1999, p. 128). She encouraged him to seek out the competent spheres.

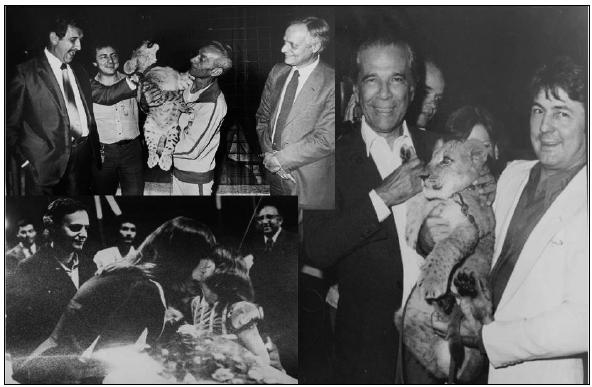

The following images reveal the proximity between government officials and the ENC (Figure 2). In the image on the right, we go to Ney Braga and Luiz Franco Olimecha, first director of the ENC; in the upper left image, Colonel Sérgio Pasquali, then Executive Secretary of the MEC, next to Luiz Olimecha, George Laysson, tamer, holding a kitten, and more next to Orlando Miranda, then President of INACEN; finally, Lucy Geisel being honored in the ENC.

Image Caption: From left to right: Colonel Pasquali, Luiz Olimecha, George Laysson (ENC's tamer and teacher) and Orlando Miranda (1982) (top left); Amália Lucy Geisel, receiving tribute at ENC (1982-84) (bottom left); Ney Braga and Luiz Olimecha (1982) (right).

Source: Orlando Miranda's personal collection. Editing by the author.

FIGURE 2 Presence of Ney Braga, Colonel Pasquali, and Amália Lucy Geisel at ENC (1982-84).

It belongs to the State the function of intervening and machining this contradiction, through the formation of a collective social conscience that naturalizes the relations of production and presents the spaces occupied by each individual as a static and immutable reality. What is in question, in this case, is to simulate individual interests of the dominant class as collective interests for the good of the whole society. It is up to education, whether institutionalized in schools and universities, or the education of everyday life, "not only to provide the knowledge and personnel necessary for the expanding productive machine of the capital system, but also to generate and transmit a framework of values that legitimizes the dominant interests [...]" (MEZAROS, 2008, p. 35).

Therefore, it must be assumed that the policies for education and culture, under the aegis of the Brazilian civil-military state in the 1970s would be, in the same way, interested in defending the interests of the dominant class of its time. It was with this objective in mind that the civil-military regime in Brazil assumed power, having as its methods the planning, rationalization of political actions and the establishment of the social order in order to, later, guarantee a new democracy on the basis of security and development.

It is worth remembering that at the end of the 1950s we reached a certain stage of development of the productive forces: close to self-sufficiency, we were able to transform our natural wealth into industrialized products and meet the needs of the population. With the creation of Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional in 1938, and the exploration of oil, we became capable of producing our own machinery and energy (COHN, 1981). At the same time, we reached a certain economic stagnation, since there was no consumer market to absorb all the production, and with the lack of investments in primary sectors we imported products of first necessity. A large part of the profits generated by the industry came from foreign investments and, consequently, the capital did not stop there.

Expectations frustrated by a process of industrial development reversed, which left only the onus on the masses, strengthened the left-wing movements that demanded greater investment in social services and basic reforms (SAVIANI, 2008). In the same way, the business class strengthened and, seeking support and alliance with the armed forces, began to pursue popular mobilizations in order to consolidate the coup d'état and establish a dictatorship in 1964.

As long as internalization succeeds in doing its good work, ensuring the general reproductive parameters of the capital system, brutality and violence can be relegated to a second level [...] Only in periods of acute crisis does the arsenal of brutality and violence prevail again, with the aim of imposing values [...] (MÉZAROS, 2008, p. 44).

In the field of education, the agreements between Brazil and the United States for the financing of education (known as MEC-USAID Agreements), the university reform (Law 5,540/68) and the new Law on Guidelines and Bases for National Education (Law 5,692/71) facilitated the entry of private capital into educational institutions. These educational policies were fundamentally based on the principles established in the Forum "The Education that Suits Us" (November 1964), organized by the Institute of Political and Social Studies (IPES), an organ created in 1961 in coordination with national and international businessmen and the War College (ESG). According to Saviani (2008), the discussions of this Forum presented the pedagogical principles of the new regime, among which we can mention: education to train human resources for development (technical labor, with lightened processes of schooling; universities with short courses for qualified labor; higher education of a propaedeutic nature for future leaders of the nation); rationalization of investments, with broad insertion of private capital (higher productivity with lower cost); meeting the needs of the market; and literacy programs of the masses.

Education in school curricula, as a pragmatic activity without its own content or technical knowledge to fund it, developed from spontaneity and individual creativity (SUBTIL, 2016); and the creation of the disciplines "Moral and Civic Education", "Social and Political Organization of Brazil" and "Studies of Brazilian Problems", besides a Health and Religion Program, optional for students: "Art. 7th The inclusion of Moral and Civic Education, Physical Education, Artistic Education and Health Programs will be mandatory in the full curricula of the establishments of lº and 2º degree [...]" (BRASIL, 1971).

But it was important to ensure forms of ideological dissemination beyond formal educational institutions. Therefore, there was interest from the government in regulating with greater attention the cultural actions that, until now, had a certain hegemony of the left. The use of means of communication as a pedagogical tool was also among the guidelines of the Forum, which enables us to understand other elements of important articulation between policies for education and culture. The National Security Doctrine of the ESG preached investment in social institutions - educational, cultural and labor - perceiving them as responsible for the transmission and formation of values and behaviors (SILVA V, 2001).

[...] on the one hand, to qualify the agents for the process of modernization of the productive sector and, on the other hand, to promote the adoption of values, attitudes and behaviors considered more adequate to the new social standards that it was intended to achieve, aiming at the type of global development desired for the country (SILVA V., 2001, p. 119).

The culture started to be considered "complement to the technological development, which means that a nation, to become a power, should take into consideration the 'spiritual' values that would define it as civilization" (ORTIZ, 2003, p. 101). Censorship, promoted at the height of the military dictatorship, left deep marks in the history of Brazilian art. But there was something new in the Tupiniquim lands...

There was ample dedication of the government to cultural policies. In 1973 the then president of Brazil, General Emílio Médici, approved a new Cultural Action Program - PAC, with the objective of preserving and disseminating the Brazilian historical and artistic heritage. PAC included the elaboration of the National Culture Policy - PNC, which would outline objectives, goals and strategies for the Brazilian cultural development. The PNC-1975 took shape with its successor, General Ernesto Geisel (1974-1979) (SILVA V, 2001).

One of Geisel's strategic actions was to appoint Ney Braga as Minister of Education and Culture (1974-1978). With a consolidated political career, Ney Braga was governor of the State of Paraná between 1961-1965, and helped elect Castelo Branco, articulator and first post-military coup president of 1964, where he was Minister of Agriculture. For this reason, Ney Braga had the support of the military. In the same way, he had prestige among artists and leftist intellectuals, due to his support and promotion of various actions in the field of culture. This was certainly a facilitator of his mandate. Apparently, the AI-59, instead of minimizing the influence of the left on the cultural level, only intensified the revolt against the regime and sharpened the creativity of the artists of the time (RIDENTI, 2014).

Therefore, taking advantage of his intimacy with the State, Ney Braga appointed intellectuals and left-wing artists to positions in the MEC, which reduced tensions and brought the government and artists closer together. During his tenure, the AI-5 was extinguished, and the National Dramaturgy Competition - Mambembe Trophy, was resumed. This had been suspended in 1968, after Oduvaldo Vianna Filho (Vianinha) won the prize for best dramaturgy with Papa Highirte, on the grounds that the SNT awarded pieces banned by the Public Entertainment Censorship Division (DCDP), was taken up again (SOUZA, 2011). Ironically, the contest awarded Vianninha again in its first reissue in 1974, this time with the play Rasga Coração.

It is worth noting that years later, in 1982, as Governor of the State of Paraná, Ney Braga would come to support and finance the production of the show "The Great Mystical Circus", produced for the Balé Teatro Guaíra, with soundtrack by Chico Buarque and Edu Lobo. The show premiered in March 1983 and presented the dreamed integration of the performing arts - dance, circus, theater - mentioned by Orlando Miranda in his interview.

[...] we thought that the performing arts should be dependent on each other, that is, they should always be integrated. And I felt that the theatre was in need of great oxygenation, something else had to start happening within the theatre, that it wasn't just the actor representing the text. (Orlando Miranda)

During Ney Braga's administration, FUNARTE (Law n. 6.312, of December 16, 1975) was created as the main organ responsible for the promotion of cultural manifestations, and approved the PNC-1975 (BRAZIL, 1975), which gave the guidelines, objectives and set goals for cultural actions. Years later, in Decree 81.454, of May 17, 1978, which provided for the organization of the MEC, FUNARTE appears among the central planning, coordination and financial control organs of the Secretariat of Cultural Affairs (SEAC), linked to the Federal Council of Culture (CFC), a collegial organ of the MEC. According to its statute, approved by Ordinance 627 of November 25, 1981:

Art. 2° - FUNARTE aims to promote, encourage and support, throughout the national territory, and practices the development and diffusion of artistic and cultural activities and, specifically.

I - to formulate, coordinate and execute an incentive program for artistic and cultural manifestations.

II - to support the preservation of cultural values characterized in artistic and traditional manifestations representing the personality of the Brazilian people; and

III - to support official or private cultural institutions that aim at the national artistic development.

Sole Paragraph - In the formulation and execution of its programs, FUNARTE observe the guidelines, objectives and plans of the Ministry of Education and Culture.

The same statute provided for the constitution of INACEN, which was to be headed by Orlando Miranda. Unlike the other institutes responsible for Fine Arts, Folklore and Music, INACEN possessed administrative, financial and patrimonial autonomy. This autonomy gave the necessary conditions for the creation of the SBC, as a deliberative organ. This one had Luiz Olimecha as its first director.

The extinction of AI-5 and the approval of the PNC-1975 contributed to a gradual decrease in the repression of cultural productions. Instead of censorship, the government's new perspective bet on "spontaneous consensus", that is, on state guidelines that invested in encouraging those productions that disseminated values and behaviors appropriate to the national development project under execution. The expansion of the MEC's structure reflected the intention to cover the most diverse forms of cultural manifestation, significantly expanding its instruments of ideological dissemination. We call attention to the strong military presence and nationalist ideals, still in 1984, when, in some documents of the ENC there are sentences of order:

Army, national presence.10

Brazil: independence. Freedom, order and progress11

November 19th: flag day. The memory of the homeland unites us12

This shows, in a certain way, that just as the cultural manifestations contemplated by the culture policies were diversified, it also amplified the influence of the hegemonic ideals expressed in the PNC-1975. As Marx points out, the class that dominates the material production of life is the same class that regulates the hegemonic thinking of this era, ideology as a world concept that meets the interests of this class (MARX ENGELS, 2007). The State is characterized as one of the institutions responsible for disseminating this ideology and, when it regulates artistic manifestations, ultimately, art can also assume the role of an ideological instrument.

Therefore, the culture policies proposed that the artistic manifestations were easily accepted by the people, that they privileged the potential for communication to the detriment of the form, and in this context, political apologies and in-depth reflections on reality became uninteresting (ORTIZ, 2003). The goal was to create forms of expression that were accepted without criticism or questioning, but that, at the same time, taught the values and the conception of the world propagated by liberal ideology: competitiveness, success achieved by individual effort, work as maximum value to subordinate classes, existence based on mass consumption.

It became essential to create a national identity appropriate to the new Brazil, to reinforce the importance of the political system directed by the military against the communist threat - "security and development", a new flag for "order and progress" - and, for this, the promotion of cultural manifestations to disseminate this identity: it would be the State's responsibility to "give the guidelines and provide facilities" so that the cultural goods would show the dominant interests in their content, and reach the entire national territory (ORTIZ, 2003, p. 88). It was important not only to preserve traditional values of Brazilian culture, but also to create new values that would contemplate the transformations of the capitalist world into which Brazil was late entering.

The PNC-1975 pointed to the basic components: crafts and folklore, plastic arts, literature, dance, music, cinema, theater, historical heritage (national symbols) and scientific, dissemination of culture; the circus was not specifically mentioned. Even so, in 1977 the National Circus Project was approved. In January 1979, Orlando Miranda authorized the beginning of the works.

The text of the PNC-1975 was permeated by the ideals of a "homogeneous" and "cohesive" society, built by a "solidary", "harmonious", "dedicated to work" people that "respects the authorities" and "welcomes" the most diverse cultures in the elaboration of a unique Brazilian culture (BRAZIL, 1975). This idea of harmony is implicit in the traditional concept of Brazilian man, and has become imperative for the contents to be contemplated in cultural productions.

According to Ortiz (2003), the image built on the Brazilian "race" between the end of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century brings the mestizo as its major representative. The harmonic synthesis of the European white, the African black and the American Indian would have given origin to this new man. Therefore, one of its main characteristics was the ability to incorporate aspects of different ethnicities and demonstrate the potential of Brazilians to cordially receive what is "from the outside" and creatively transform from the "inside" specificities. In this sense, he ignored the differences and inequalities that went through the national territory with the discourse of a unique Brazilian race. "The element of mestizaje contains precisely the traits that naturally define the Brazilian identity: unity in diversity. This ideological formula condenses two dimensions: the variety of cultures and the unity of the national" (ORTIZ, 2003, p. 93, emphasis added).

In relation to dissemination, an important element to ensure national unity/integration, there were massive investments by the State in the telecommunications network, enabling the implementation of television, for example (Ibidem).

These two aspects - content and dissemination - became important for the consolidation of a new phase of capitalism and liberal ideology in the country, and had obvious illustrations in the circus institution. The first one made it clear that we were ready to receive the influences of international capitalism and adapt it to La Brasileira, as did the circus in Brazil: with precursors coming from different parts of the world, it knew how to adapt and be contemporary in different times and spaces of history13. For example, he carried in his shows many allegories that expressed the creativity, kindness and strength of the Brazilian people. We also highlight the importance of the mestizaje: the Brazilian circus was, by tradition, mestizo - Portuguese, Spanish, Italians, French, Russians, Peruvians, African descendants brought as slaves, Brazilians, among many others - and their shows were examples of the possible and desirable unity between races, colors, techniques, ethnicities.

The second one transformed Brazilians from North to South into a single force, each individual, rich or poor, boss or employee, artist, intellectual, ruler, fulfilling his function for the development of the nation. Itinerancy14 as an essential value of circus identity can be analyzed as an important element of unity, since the circus carried its shows and the signs contained in them to all corners of the national territory. In the words of Orlando Miranda:

The circus was a great national integration. Today you have a national integration through television, before you had a national integration through radio, and before radio there was no such story, that is to say, the circus went to places - and even today - it goes to places that, if you doubt it, neither television nor radio does not yet arrive, the circus is present.

The indirect manipulation of culture was capable of instilling values and inducing behavior without repression, through the dissemination of the ideal of integration/national identity, for the development of a generic man, the "true" Brazilian man (SILVA V, 2001). Implicit in the idea of unity in diversity, propagated by the PNC-1975 guidelines, is the supposed inexistence of class antagonisms and regional inequalities.

Another aspect that deserves to be highlighted in the PNC-1975 is the spontaneous property of culture or, in Ortiz's words, "recognize the existence of a "true" Brazilian culture, spontaneous, syncretic and plural" that, according to him, would forge the characteristic of a democratic nation (ORTIZ, 2003, p. 96). Values such as order, discipline, cooperation, conciliation, responsibility, harmony, balance, solidarity, respect for authority, dedication to work, were seen as natural characteristics of the "Brazilian man" (SILVA V, 2001).

We observed, in this case, the replacement of the repression of what was harmful by the stimulus to what was providential. Since the essential values that guide individual behaviors were natural and spontaneous, and the Brazilian man was "naturally good", the policies for the culture of the Ernesto Geisel government only encouraged the flourishing of the Brazilian essence. In this case, the function of the State was "[...] simply to safeguard an identity that is defined by history" (ORTIZ, 2003, p. 100; emphasis of the author).

Among the guidelines of the PNC-1975 that pointed to the stimulus to the creation and expressions of the "spirit of the Brazilian man", was the "Support to the formation of professionals" linked to cultural productions, and one of the goals specifically referred to the creation of extension and short courses (BRASIL, 1975). If the government was concerned with encouraging the creation and generalizing access to cultural goods, consequently, it was also concerned with the training of human resources capable of adequately performing this task. We recall that the incentive to technical schools was also one of the aspects of great relevance in LDB 5.692, of 1971 (BRASIL, 1971). Thus, we can assume that the construction of training schools for artists, encouraged by the government, would be a very effective action in meeting these objectives. The ENC was created with the intention of ensuring the training of circus artists, but also, among its purposes, was to offer training courses for dancers, artists and theater technicians. In this case, it would congregate the formation in scenic arts from the guidelines of the PNC-1975.

In this scenario, the contemporaneity and itinerancy of the circus would be important instruments to meet and disseminate the bourgeois ideology of the period, and the guarantee of survival of this institution also became the focus of policies for culture. From this context, the request for legalization of the ENC pointed to the following purpose:

To promote, in quality and quantity, schooling and technical training compatible with the basic and necessary knowledge of the individual interested in training and working in the circus arts area, in view of the adaptation of the educational system to the new ways of life and work resulting from the changes that take place in the country and the world.15

On the other hand, we cannot ignore the fact that some elements present in the PNC-1975 were also among the discussions of the revolutionary and counter-hegemonic left, which based its criticism not only on the military dictatorship, but on the Brazilian political-economic system and on the disorganized industrial development that the country had been going through since Juscelino Kubistchek.

Analyzing the problems of the different industrialization processes that Brazil went through in the 20th century, Gabriel Cohn explains that Kubitschek's motto of "50 years in 5" led to the neglect by the State of the primary sectors of production16 and to massive investments in the industrialization of large urban centers. Among other consequences, we have the precariousness of life in the countryside, the rural exodus and the expansion of urban agglomerations in search of jobs and underemployment in industry (COHN, 1981).

From this reality, the revolutionary left also took as a party for social transformation the "Brazilian people", with rural and mestizo bases. However, instead of idolizing modernity, the movement of artists and intellectuals that Ridenti will describe as "revolutionary romanticism" sought to criticize modernity from specific aspects. From the author's perspective: "Critique from a romantic view of the world would focus on modernity as a complex totality, which would involve relations of production (centered on exchange value and money, under capitalism), the means of production and the state" (RIDENTI, 2014, p. 11). The search for a Brazilian identity in the countryside, in those population spheres hitherto marginalized due to a modernity "crystallized in the cities", and in the forms of social organization of the past would allow "an alternative of modernization of society that did not imply dehumanization, consumerism, the empire of fetishism of merchandise and money" (Ibid., p. 10). After all, left-wing groups understood industrialization as the first step towards national sovereignty, through the implementation of basic reforms - tax, financial, banking, agrarian and educational (SAVIANI, 2008).

Thus, if we resume the strong presence of artists and leftist intellectuals in cultural productions since the government of Ernesto Geisel, we can see conflicts, but also approximations between the ideals of the State and the ideals that said they were against hegemonic and revolutionary. In this scenario, the circus emerged as an important diffuser of a certain culture of interest to the State for political openness, but also as a cultural production that carried in its history aspects necessary to women and men of a supposed revolution.

3.2 a chance for the poor circuses of Brazil17

After a period of broad urban expansion, cities no longer had land available in easily accessible and visible locations, and charged viable rents for the installation of circuses. This data is one of the main difficulties faced by circuses at the time: "The main one is the scarcity of land in large Brazilian cities, which is taking this ancient art to increasingly distant and inaccessible places, with great losses for companies”18; "proper place for setting up the circus, proof of retirement, enrolment of children of circuses in public schools [...] among others" (BARTHOLO, 1999, p. 129). While the National Circus-School began its work, the most traditional circus space in Rio de Janeiro - the Eleventh Square - would be vacated for the construction of a commercial center.19

The second great difficulty was to find qualified Brazilian artists. The report of the Diário do Grande ABC, of May 20, 1978, described the new strategies to support the circus, and highlighted the lack of qualified personnel. At the time, Orlando Miranda reported that the SNT was conducting a survey of the existing circuses, the major difficulties faced and the working conditions to support the "global policy of support and development of the circuses that we want to initiate in Brazil".

Through the relationship established with the government, and with the "enthusiasm of Orlando Miranda"20, as SNT Chief and later President of INACEN, the Circus Project brought alternatives to minimize these problems. Folha de São Paulo, April 22, 1978, presented the "National Circus" project, whose intention was to build permanent circuses in all Brazilian states, and with them, circus schools for the formation of new professionals. The permanent circuses would solve the problem of the lack of space for the installation of companies, and the circus schools would be the solution to the lack of artists. Not by chance, this project was widely accepted by the Ministry of Education and Culture.

As we analyzed, the military regime was heading for an end and the imminent political opening brought new possibilities for artists. One of the strategies that contemplated the entire artistic scenario of the period was the regulation of the profession of the artist and show technician with Law 6.533, of March 1978. The law provided for regularized employment, since the artist became a profession in the eyes of the law, enrolment in schools for children of itinerant artists, retirement, among other aspects, but would not guarantee, by itself, the survival of the circus. The restructuring of the MEC, with the creation of the INACEN and, subjugated to it, the SBC as the government body representing the institution, also contributed to the circus gaining a small space between the actions to support culture.

The MEC's "Circus Project" (1977) contemplated, among other actions: "The destination of planned areas and with the necessary infrastructure for the arming of circuses in each capital of the country;". [...] "The creation of a circus complex located at Praça da Bandeira, n. 4, in Rio de Janeiro;" ...] "The creation of the first Circus School in Latin America, located in the circus complex". The document with the specifications for the construction of a Circus Square is dated February 23, 1979. The following items were listed: The following items were listed: "light control station, cafeteria, bars, ticket offices, administration, warehouse, locker room, lighting, lining, leveling, walls, cementing and stone", in other words, the other necessary spaces and services excluding the circus structure (canvas, masts, arena, appliances).

These spaces would be made available to Brazilian companies at affordable rental prices, with collectively established occupation criteria. The first meeting with the entrepreneurs to discuss the criteria of occupation of the space was scheduled for July 2, 1979, at the Glauce Rocha Theater, in Rio de Janeiro. The convocation, made by official document of the SNT and by bulletins in newspapers, informed that the permanent circus SNT/MEC was in the assembly phase. However, the process was slow and challenging.

From an agreement signed in a meeting at FUNARTE on May 6 of the same year21, the land where the MEC's garage was located, in Praça da Bandeira, city of Rio de Janeiro, was transferred to the SNT's domain, so that the project and the necessary infrastructure for the construction of a permanent circus and a space for the assembly of travelling circuses could be provided. The first challenge was to vacate and clear the land.

Then, between the years 1977-78, works were being carried out on the subway in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The ENC was built next to the subway line, so, while there were those works in progress, it would not be possible to start the circus works. Another challenge was to get part of a plot of land from the city hall, to ensure safety and greater flow at the exit of the public at the end of the shows, or in emergency situations. At the beginning of 1979, the SNT received a negative response from the city hall, which made Orlando Miranda very angry and threatened the implementation of the project in Rio de Janeiro.

After overcoming the obstacles related to the MEC and Rio de Janeiro City Hall land, there is a request from Orlando Miranda, dated February 5, to the Director of the Parks and Gardens Department for the removal of a tree still in 1979, in which the Director of the SNT stated that the works of the permanent circus in Praça da Bandeira were in completion phase. In the same year, the cart that carried part of the material for the canvas and the arena collapsed, the material was lost and it was necessary to wait for a new shipment22.

With the arrival of the new material, in May 1980 the circus was armed. A few months later, on October 5th, a storm hit the city of Rio de Janeiro, destroying part of the canvas and the wooden and iron structures. The London Circus, which was in the city, was also partially destroyed, and the SNT assisted him in his recovery, which again delayed the works23.

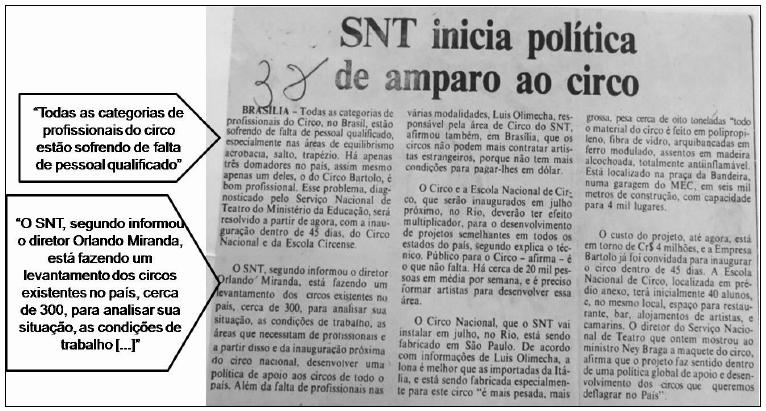

However, the difficulties faced did not slow down the work of those who saw in this project a hope for the survival of the circus. According to reports by Ruy Bartholo, among other artists, these difficulties seemed to be part of everyday circus life, since storms, fires, accidents were old acquaintances of families who were willing to build their lives under the canvas (BARTHOLO, 1999). Due to the unforeseen events, there were several promises and extensions of deadlines. The first one cited the month of July 1978 as a probable period for the inauguration of the National Circus-School. The second pointed to March 1979 as the month of inauguration, which coincided with the refusal of the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro to cede the land. Already at the beginning of April of the same year, after negotiations, new hope and promises of inauguration by July. Almost two years later, at the end of 1980, Luiz Olimecha was waiting for the conclusion of the works until Carnival the following year. Finally, more than a year after the last forecasts, finally, the works of the circus complex were concluded. The following images demonstrate the cunning work to erect the canvas. First the canvas was opened over the bleachers, then the dome was attached to the center of the arena, and then it was erected between the four large support masts (Figure 3).

Under the canvas, a 50-meter diameter arena, space for 4,000 spectators, "made of modulated iron, anti-thermal and anti-inflammable plastic cover, polypropylene chairs and complete sound and lighting equipment," as described in the project years before24. On May 5, 1982, INACEN Ordinance No. 11 resolves: "to create the National Circus School of the Brazilian Circus Service of the National Institute of Performing Arts, with operation integrated to the circus complex Circus National School".

On May 13, 1982, the Minister of Education and Culture Ruben Ludwig would accompany the inauguration ceremony of the circus complex, descending the commemorative plaque next to the circus Franz Tihany, and throwing sawdust in the arena with the help of the artist and teacher Neuza Matos. The "Circo-Escola Nacional" was officially inaugurated at Praça da Bandeira n. 4, under the direction of Luiz Olimecha. The Inauguration Party was attended by several authorities, who attended a show offered by Circo Tihany, in honor of the circus artists and their contribution to Brazilian culture.

On the occasion, Rubem Ludwig, Minister of Education and Culture, said at the inauguration ceremony of the ENC, years later: "The circus and the school represent culture integrated with education, with Brazil. It is Brazilian culture. Congratulations to the circus school"25. It was the voice of a representative of the Brazilian State, bringing to the arena the expectations that were founded with the masts, under the canvas of a new story for the circus and also for the Brazilian artistic production. The following year, on July 4, 1983, the Circus Art Initiation course class held its first public exhibition, alluding to the school's anniversary. At the entrance parade and at the farewell, the students carried the flags of all the states of the Brazilian nation, showing the much dreamed of national integration in the circus arena.

4. Concluding remarks

This research sought in the movement of history, in the characteristics of circus institutions and in the policies for education and culture of the Brazilian State of the 1970s to find elements to explain factors that converged for the creation of the ENC in Rio de Janeiro in 1982. After analyzing the various sources that made up the collection of this research, in permanent dialogue with the theoretical framework that underpinned the discussions presented at the time, it was possible to identify the interests of the Brazilian State in promoting cultural policies that, allied to formal educational institutions, were capable of disseminating its ideology, as conditions for the process of creating the ENC.

On the one hand, the creation of the ENC is aligned with the principles of training technical personnel necessary to promote the economic and social development of the country. As we mentioned, it was not only a question of providing a driving force for the system, but also of instilling values and behaviors that would legitimize its reproduction. Despite having its "Technician in Circus Arts" course officially recognized by the MEC and published in the National Catalogue of Technical Courses only in 2014 (BRAZIL, 2014), the ENC trains professionals with high levels of qualification since its creation.

On the other hand, by stimulating circus productions, the State has a means of communication that went beyond the limits of the radio and television waves of the time, and carries in its shows ideological elements to the entire national territory. The Brazilian State was going through a very peculiar moment: after years of a severe and violent military dictatorship, it was time to prepare the population for political openness on the basis of security and development. To this end, cultural policies began to worry less about repression, and more about the direction of artistic manifestations. In this case, the circus played the role of broadcasting shows that showed certain Brazilianness and, at the same time, it was an artistic manifestation that reached isolated places, reaching territories where the radio stations did not arrive either.

In addition to these elements, the protagonism of agents such as the Ministers of Education and Culture Ney Braga (1974-1978) and Rubem Carlos Ludwig (1980-1982); the Director of the National Theatre Service, Orlando Miranda de Carvalho must be considered; the General Secretary of MEC, Colonel Sérgio Mário Pasquali; the circus, creator and first direct of ENC, Luiz Olimecha, the teacher and advisor of FUNARTE, Omar Pinto Elliot, among other circuses and public people who joined efforts for the ENC to be created.

We believe that explaining the creation of the ENC and the reordering of the processes of formation of artists considering their relationship with the Brazilian State of the time is an important step to understand ways in which this institution sometimes contradicts itself, for others it approaches the mode of production of life and of social reality. However, what we exposed were some aspects that, in an attempt to apprehend the movement of history, we had the insight to perceive, which does not exclude other possibilities of interpretation and the emergence of new elements.

Be it the circus that comes from the circus or the circus that comes from school, it continues to be a form of expression of power, of human universality, dialectically woven by unique contexts, times and spaces, which makes it a charming, instigating and unique artistic manifestation.

texto en

texto en