Introduction

The processes formed by historiography promoted profound changes in the patterns of understanding about the formation of the territory occupied by Minas Gerais. This movement was characterized by the overcoming of generalist interpretations that, for the most part, were based on adaptations of elements related to the history of Brazil in the understanding of the history of Minas. According to Gonçalves (1998, p. 13):

The path followed by the historiography of Minas Gerais, although far from presenting a linear evolution, allows us to identify a basic tendency: that of a historiographical production that has as its starting point the theses that emphasize external determinations in the explanation of the future of history. of Brazil. Then we follow another path with several branches, one of which, perhaps the most important, is based on an apparently opposite interpretation that favors the internal determinations of the system, but still points to the possibility of synthesis between the mentioned approaches that seemed to be irreducible at the first glance. (Gonçalves, 1998, p.13)

This movement of change in the historiography of Minas refers to that one which has been developed in the field that deals with issues related to the historical processes of education in society. The history of education about Minas Gerais was also developed through generalist narratives that were structured in interpretations based on the history of education in Brazil and consequently its adaptation to the context represented by the society of Minas Gerais.

From the 1990s, these interpretations were followed by the construction of structured narratives in the development of education within the internal dynamics of the region. In a characterization of this movement of educational historiography on Minas, Carvalho and Faria Filho (2019, p.17) state that:

In this way debates around studies related to local aspects versus the macro structuring factors in terms of state educational policy emerge ... we seek to understand the approximations / tensions between various mining spaces, and how issues related to educational problems were 'accommodated' during the promotion of education within society, as well as the attempt to clarify the political, cultural, ideological and anthropological interests that permeated the struggle for the constitution of the state educational system (Carvalho; Faria Filho, 2019, p. 17).

Therefore, in recent years, the changing history of education about Minas Gerais has highlighted the internal dynamics of the region itself. Within this process of renewal, greater attention is needed to space and its process of configuration within the historical movement represented by Minas. Overall, the history of education in Minas Gerais has given little importance to this issue and its implications. Thus, analyzes that are directed to a sub region are understood to be valid for the entire region disregarding the differences observed in the state's territory.

Historiography on Minas Gerais has been building a movement of analysis that has indicated the importance of the sub regions that make up the state's territory, thus revealing the need to take into account the particularities of space in the understanding of historical processes. The vastness of the territory associated with a particular occupation dynamics of its different regions indicates the need for a more effective consideration of the space category on the studies about the historical development of Minas.

We understand that this sort of analysis requires the attention of education historians, that is, it is necessary to take into account aspects related to the historical processes of space occupation as part of the explanations of the dynamics of education in the different regions of Minas Gerais.

From this perspective, we situate education in Campanha da Princesa, one of the most important cities in the process of building a very specific region: the south of Minas.

To accomplish this task, we use a regionalist approach, that is, that defines a space from a relative internal homogeneity identified in relation to some criteria (Barros, 2006). To this end, we situate Campanha da Princesa in the process of building the so-called Southern Minas Gerais State, seeking to demonstrate how educational activity can be understood as one of the characteristics that make up the process of producing an identity of the region.

According to Gomes (2006), the idea of region as a geographical concept was initially considered as a delimitation of concrete reality based mainly on physical elements. This notion was revised when it was understood that the idea of the region could only gain an effective meaning from an overcoming of the idea of natural space. Thus, the region would not correspond to a given space, but would be created from the identification of the elements that contributed to the construction and appropriation of space as a bearer of a specific identity.

These considerations by Gomes (2006) are pertinent in relation to the regionalization process that has been elaborated in Minas Gerais, especially in the historiography referring to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which we found an overcoming of the divisions that took into consideration only political-administrative boundaries, mainly in its representation through the idea of counties.

According to Martins (2010), a reconfiguration in relation to the perception of the space of Minas Gerais was started in the 1990s. The regional units of Minas Gerais are no longer conceived as a given, natural thing. They are now built on criteria that take into account physical, demographic, economic, political, historical and cultural elements.

For Frémont (1980) the term 'region' involves the idea of a lived space-time, because it is not possible to separate space and human experience, which permeates the imagination of the population and the development of an identity with a given territory. Thus, the region comprises aspects of its residents' culture, which build a sense of belonging and produce the formation of 'regional images'. For Frémont (1980), the process of 'rooting' is constant, that is, the connection established between men, their values and the land to which they relate directly.

It is from this perception that we set out to treat the city of Campanha as a constitutive element of southern Minas Gerais, a specific region. Thus, we characterize Campanha as part of a process of affirmation of the Rio das Mortes County, from the 18th to the 19th century, and also as an active element in the process of building the idea of southern Minas. In this movement, we highlight the place occupied by education in city life, especially from the specificity of the public that gravitated around the school spaces.

Rio das Mortes County in Minas Gerais development

Minas Gerais’ territory occupation took place from the late 16th century through an imposing migratory flow that was driven by the exploitation of precious metals. The materialization of this process occurred through a spatial planning that divided the captaincy into four regions: Vila Rica, Sabará, Serro and Rio das Mortes, and the southernmost of the captaincy, an object highlighted in our studies.

Within those regions, there was a permanent emergence of small settlements that, as they developed, became villages2. The emergence of these villages can be understood as the demarcation of the importance achieved by the territory of Minas Gerais, also representing the development of the different counties that made up the captaincy.

By 1730, we had a total of nine villages in Minas that were distributed with relative balance between the different regions. Thus, each region created a village, except Comarca do Serro where three villages were created3. This situation remained stable until the late eighteenth century, when we had a new flow of settlement in Minas. This movement began with the emergence of Vila de Itapecerica in 1789, and then Vila de Queluz (1790), Vila de Barbacena (1791), Vila de Campanha da Princesa (1798) and Vila de Paracatu do Príncipe (1798). Four of these villages were created in Rio das Mortes region, that is, only Paracatu do Príncipe was located outside this region, belonging to Rio das Velhas.

Therefore, almost all the new villages that emerged in this period were created in the Rio das Mortes region, which indicates the importance achieved by this region in the late eighteenth century.

In the earlier period, that is, in the early decades of the eighteenth century, the main flow of development of the captaincy had occurred more consistently in the central region, where Vila Rica and Sabará were located. In these two regions, the activities related to the exploration of gold generated a growing population and economic development. By contrast, the region represented by Rio das Mortes had only two villages - São João del-Rei and São José del-Rei -, which, as we have seen, changed in the late 18th century when four settlements were promoted.

Such a situation becomes clearer when we consider the demographic aspects of the captaincy. In 1776, Minas Gerais had a population of around 319,769 inhabitants spread over several regions as follows:

In 1776, there was a relative balance of the population of Minas. This is indicated by population percentages that were similar in Sabará and Rio das Mortes counties, respectively 25% and 26%, and slightly below in Serro, 18%. Amid this relative balance we find slight population predominance in the region of Vila Rica, with 31%.

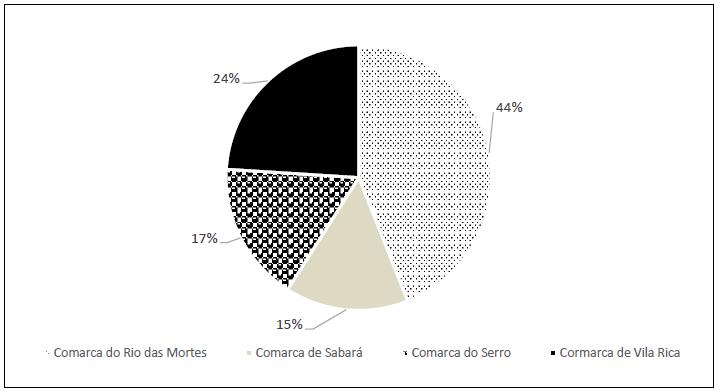

This situation changes substantially in the early nineteenth century, when the population of Minas reached 492,436 individuals, most of them concentrated in Rio das Mortes County:

The changes observed in the population of Minas Gerais between 1876 and 1821 are clear. There was a drop in the percentage relative to the population of almost all regions: Vila Rica County went from 31% to 24%; Sabará went from 25% to 15%; Serro went from 18% to 17%. In contrast to this backward movement of the population of these three counties, we found a significant growth in Rio das Mortes, which reached numbers close to half of the population of the entire captaincy: 44%.

Therefore, the process of creating villages in Minas - specifically Itapecerica, Queluz, Barbacena, and Campanha da Princesa - was part of a broader movement that changed the economic dynamics of the captaincy making Rio das Mortes County one of its main poles of development.

In fact, this movement that happened between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is part of a process of change in the productive structure of the captaincy. Minas Gerais developed during the eighteenth century, under a strong impact of the exploitation of precious metals. This made the mining region, which was in the center of the captaincy, the main pole of economic and social development of Minas.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, there was a reflux of mining activity changing the axis of economic development, whose main mark was a diversification of the production matrix and the development of other regions (PAIVA, 1996). It was around this process of diversification of production that Rio das Mortes County stood out, as its development came from the combination of different economic activities, especially agriculture and livestock that made this region a central element in the process of supplying the captaincies of Minas Gerais, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

The affirmation of Campanha da Princesa as a village, in the late eighteenth century, is a representation of this movement of spatial displacement of the axis of economic and political power in the captaincy of Minas. This movement was highlighted by the transformation of the southern region into one of the main development centers of Minas Gerais. On the other hand, it also represents a transformation cycle of the mining economy, that is, the transition from a monoculture economy, structured in mineral exploitation, to an economy that combined different productive activities.

From this new configuration, it is possible to understand that the region to the south of the captaincy was transformed differently from the other localities, becoming an important commercial and agricultural center, which developed together with a large population increase.

In addition to these particularities in the economic and demographic development of the southern region of Minas Gerais, it is also possible to identify a political specificity, especially through the formation of a class of owners who acted directly in imperial politics. Soon, Southern Minas became an agrarian-based region made up of large landowners, merchants, and slaves (Paschoal, 2008).

This perspective was noted by Andrade (2005, p. 53) who sought to characterize the establishment of an elite in Campanha da Princesa in the nineteenth century. To do this, Andrade used inventories as a documentary reference, in which the individuals who made up this segment registered their assets and the set of economic activities that were linked to them.

Through the general mapping of the inventories analyzed, it was possible to verify the importance of Campanha in the South of Minas Gerais scenario, both due to the diversity of projects and population growth in the first half of the 19th century (...). A striking feature to be emphasized is that slaveholding farms pursued different activities - while raising cattle, horses, pigs, and sheep, the farmers planted rice, corn, and beans, and many of these products were traded on and off the province.

Campanha da Princesa can be understood as a city that exemplifies the development process of Rio das Mortes region, where the exploitation of gold came to coexist with agriculture, handicrafts and commerce. It is also a city that expresses the sociability standard that was established in the region that was conventionally called Southern Minas.

The role played by Campanha da Princesa in shaping southern Minas as a region

Campanha da Princesa was one of the most important cities in the region known as Southern Minas. The idea of southern Minas Gerais as a space that bears a specific identity was formed from Campanha. This idea emerged in the nineteenth century and gained consistency in later periods and is still today an identity reference for the set of cities in that region.

The shaping of the space represented by the South of Minas is directly related to the development of Campanha da Princesa:

It is important to present to the reader some historical aspects of an important village in the province of Minas Gerais, a region that gave rise to what is now loosely defined as 'southern Minas'. All the memorialists in the region are emphatic in saying that the city of Campanha is the 'root of the south of Minas', not only for its political and economic importance, but also for being the oldest in the region and having been the seat of Rio Sapucaí region from 1833 (Andrade, 2005, p.44).

The emergence of Campanha occurred around 1737 through a village that was initially called Arraial de São Cipriano. Shortly thereafter, it was called Campanha da Princesa and, in 1798, was promoted to the status of a village that encompassed almost every location below Rio Grande. In 1833, Campanha substantially increased its power and prestige when it was defined as the headquarters of a new area that was created in the region, whose name was Rio Sapucaí County.

In 1842, Campanha was transformed into a city and intensified its ambitions of territorial expansion to play a leading role in the movement that revolved around the idea of turning the South of Minas into a province, an idea defended by a portion of the region's population during the second half of the nineteenth century4.

One of the greatest enthusiasts of the creation of a province in the south of Minas Gerais was Bernardo Saturnino da Veiga, who in 1874 organized a publication entitled Almanach Sul Mineiro that brought different information about the municipalities of the region. Almanach himself was conceived as part of the process of producing an identity for the region bringing with it the defense of the creation of the new province. As can be seen among the elements that justified the organization of this publication:

Conscience tells us that this is of some use (the Almanach), because at least it gives us knowledge of what we are in the present, and hopes of how much we may become in the future. And if it is a good destiny that one day this part of the great province of Minas can establish its separate economy, by creating a center of administration here, to make the most of the immense wealth we have, this book will serve to show that it is not without reason that the creation of the province of Minas do Sul has long been required. (Veiga, 1874, p.8).

The publication of Almanach is the result of a process that began in 1853 when the creation of a province in the south of Minas reached the Chamber of Deputies. Castro (2012) points out that the request reappeared in 1862, 1868 and 1885. In these three moments the proposal was presented to the parliament by deputies from Campanha. For those who advocated the creation of the new province, the claim was that the region had specific geographical boundaries as well as political and historical specificities that justified its emancipation.

The creation of the province ‘Minas do Sul’ was not approved during the imperial period. However, we highlight the importance of this project mainly to demonstrate how part of the inhabitants of that territory saw it, that is, claiming a territorial identity that would justify the production of a new political-administrative reality within the process of organizing the Empire government.

Education in Campanha da Princesa in the nineteenth century

Since its establishment as a village in 1798, Campanha has demanded investments in urbanity and also in the civility of its population, making room for initiatives in the educational field. One of the elements that were mentioned as a necessary condition for the consolidation of the new village was the creation of Latin reading, writing and grammar contents for ‘the good education of youth’.

Thus, we find the record of a reading and writing class, which had 27 students5 and was dated in 1800. According to Lage (2007), in 1826, the public school of first letters had 50 students. In 1831, as a result of the private initiative, Sociedade Philantropica Campanhense was created to help disadvantaged children and to promote public education. In the same year, a first letters mutual school was also created.

The schools that emerged in Campanha were in the standards of the first half of the nineteenth century, with limited space and pedagogical organization. This is what we can find in a report by Francisco Ferreira Rezende6 (1987) who recorded the characteristics of the class he attended in Campanha in the 1840s:

Never, it is true, did he (the teacher) cheer us up or smile; but I understand, and I understand very well, that it would be a real cruelty to keep us for five or six hours sitting and clinging to those hard wooden benches. At a certain time of the day or when he thought it was appropriate, he sent us into his house, and there we had not only the most complete freedom to play in the courtyard and the vegetable garden, but his wife, who was still very young (as the teacher was not old himself) never failed to give us sweets, cheese or crackers that could entertain the stomach until it was time for us to go home.

The narrative describes a school model in which the public function of education was confused with the dynamics of the teacher's own house. Vidal and Faria Filho (2000) characterize this model as an impromptu school, that is, a dynamic that precedes the process of affirming the school space as a specific place and also as a central element in the principle of the modern art of governing. This was a school model characterized by improvisation and social ordering in which private order was superimposed or confused with state power7.

In the improvisation school, the teacher was strict and preserved the hierarchy of social relations of the house, which merged with the school. In this universe, the teacher portrayed by Ferreira Rezende (1987) was characterized as a patriarchal entity that projected his power over his wife and students.

This teacher's authority was experienced by Ferreira Rezende (1987, p.176) by assessing his performance in a grammar class:

I was already studying grammar; and one day I thought I had the lesson so well known that I did not believe there was anyone in the class who did it as well as I did; and in my enthusiasm I went awkwardly to stand on the edge of the bench to be the first to teach the lesson when the time came. Smug or proud, however, is the most expensive thing in this world; and that pride of mine or that conceit of mine had to be paid that day; because I knew and knew very well how to say my lesson; but I was still a child and lived with more or less ignorant people. In this way, I pronounced a few words the way I heard these people pronounce; and so, having to repeat one of the grammar examples, I said that two eagles 'aflown'8, one from the east and one from the west. The master simply asked me, "How?" And I, who was quite sure of the example, and who could not have the slightest awareness of what was wrong, repeated it in the same way as before. By presumption or pride, I wanted to be the first to give the lesson, and I gave it in addition to that damn - "a" - and I was humiliated.

The school of Campanha had limitations on the organization of the space and the pedagogical plan, but received a wide and varied set of students. This can be seen when we seek to identify the public who attended schools by means of a data set found in census documentation from the 1830s.9

In 1831, Campanha Village had a population of 5,500 individuals, of which 207 were in elementary school. If we consider what was established by the Minas Gerais legislation of 1835, which defined that students should be free boys, aged 8 to 14, we have a good level of coverage for what we might call a school-age population.10

Among the 5,500 individuals registered in the population, 904 were in the age group between 08 and 14 years. Excluding slaves and women from this universe, we have 361 individuals who were able to attend school. Of these, 117 attended the first letters school, or 32.4%.11

We cannot fail to highlight the female presence in elementary schools in Campanha. In Minas, in the 1830s, there was no definition as to the compulsory school for this group. The 1835 law referred to female schooling only through a recommendation, or a possibility to be implemented in some localities.

In the province of Minas Gerais, in the 1830s, we found a very small number of girls in schools. In most cities where we find census records this number was practically insignificant. Within this universe Campanha is an exception as there were 55 girls among the 207 individuals who were in school, ie over a quarter of the total. This fact is highlighted by the report by Ferreira Rezende (1987, p. 207):

I remember there was a public girls' classroom in Campanha that had about fifty students; There was also a very old lady who had been a teacher of these girls, but I don't know if the classes were public or private.

The female presence in Campanha schools gained prominence and gained increasingly effective institutional status during the 19th century (Lage, 2007). However, it was only part of the diversity of the students we meet in schools, because it is compounded by the presence of blacks registered in the nominative list of inhabitants.

From: Listas Nominativas de Habitantes de Campanha, 1831

Graphic 3 Racial Profile from Campanha Elementary School - Race / color

In Campanha there was an absolute predominance of white pupils in the elementary school and a minority presence of blacks - all designated in the ‘brown’12 category - however, this is an important number to characterize the diversity of the school space of Campanha village.

This diversity can also be verified through the students' social condition. To assess the social condition of these students we can use as reference the possession of slaves in the homes of individuals who were in elementary schools, because at that time a rich man evidently held the possession of men and land (Andrade 2008).

In a slave society, slaves were fundamental to the functioning of the economic system and also to the expansion and conservation of wealth. Thus, the presence of slaves in households is a strong indication of the social condition of children in schools. Most of the children in Campanha Elementary School came from households in which there were only free persons: 55% of these households did not have slaves. Therefore, the majority of the school public was not part of what we might call the slave elite present in Campanha da Princesa.

However, if we can say that this elite was not the majority, that does not mean that it was not present in school spaces. To measure their presence, we isolated the households where we found slaves, that is, 45%, and classified them from a pattern that considered four ranges: households with one to three slaves; four to nine slaves; ten to nineteen slaves and more than twenty slaves.

From: Listas Nominativas de Habitantes de Campanha, 1831

Graphic 4 Number of slaves in households with children in Campanha schools

In Campanha Elementary Schools, we have a significant number of individuals from households with between four and nine slaves (41%). The same can be said for more than ten slaves (29%) and more than twenty (9%). Therefore, we can say that the schools were not monopolized by the elite, but this group was also present in this space.

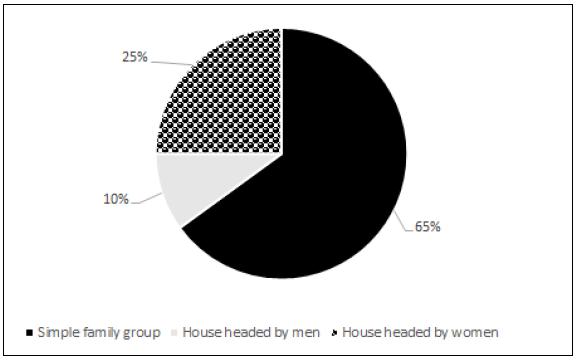

Another observation pattern we established regarding households was the profile of family groups in which we found children in the process of schooling. For this we use three specific categories of classification of family groups: the first refers to the simple family group, which corresponds to the most common family pattern admitted in Western civilization, ie, where there was a man and a woman formally recognized as married and usually accompanied by children. The second and third household categories are represented by a male-headed group and a female-headed group, those in which we find a male or female individual (single or widower) registered as household head.

From: Lista Nominativa de Habitantes de Campanha, 1831

Graphic 5 Family Group with Children Profile in Campanha Elementary School

In Campanha da Princesa we observe an absolute predominance of the simple family group. Those who were headed by women representing 25% and those who were headed by men were 10%.

The set of data presented here indicates that there was a more traditional profile of social groups that were linked to the Campanha school spaces, that is, it was mostly composed of white male children who came from households that corresponded to the more conventional pattern of family: the simple family group.

The particularity of a region and the criteria that give it homogeneity are clearer when expressing the difference with other spaces. Therefore, we understand that the characteristics of Campanha schools acquire more evidence when compared to other cities in regions that had a different development from the one we found in southern Minas Gerais.

From this methodological perspective we will compare Campanha data with those from Mariana, a city in the central region of Minas Gerais, which had its development linked to the first moments of the occupation of the captaincy, that is, at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Mariana became a village in 1711 and a city in 1745, almost a century before Campanha. However, the 1831 census records its population with a total of 2,973 inhabitants, nearly half of the 5,500 we found in Campanha13.

These data show that the population displacement pattern in the Vila Rica and Rio das Mortes counties can also be found in relation to Campanha Village and Mariana City in 1831. The same is true of the data concerning to the registration of students attending elementary school. As we have seen, there were a total of 207 students in Campanha, much higher than the 65 registered in Mariana.

On the other hand, the profile of these students puts the two localities in opposition. In Campanha, almost a quarter of the students were women (55 students); in Mariana we found only two girls assigned to the school. The absolute majority of Campanha students were registered as white (65%), a very different situation from the public in Mariana schools, which were attended by 60% of children who were classified as black or brown.

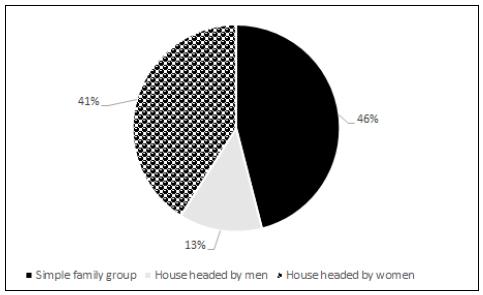

The profile of family groups with children in elementary school reaffirms the differences that existed between the central region and the southern region. While in Campanha the simple family group was predominant, in Mariana we found a significant number of households headed by women.

From: Listas Nominativas de Habitantes em Mariana, 1831

Graphic 6 Profile of the Family Group with Children at Mariana Elementary School

In Mariana, the simple family group comprised 46% of households with children in elementary schools, followed by 41% of households that were headed by women and 13% headed by men. The large number of female-headed households is surprising, as it was very close to the percentage of the simple family group that corresponded to the most traditional family pattern in Brazil.

These data indicate that Mariana had a less traditional social configuration that allowed a reasonable circulation of blacks and women, groups that suffered prejudice and social disadvantage within the patriarchal structure that marked the development process of Brazilian society14.

Mariana was not a city far from the social pattern resulting from slavery, nor by patriarchal culture and its consequent unfolding in a position of inferiority occupied by women and blacks in its social structure. However, the force of slavery and patriarchy did not prevent blacks and women from making contact with spaces such as schools that, among other things, could be used as an instance that gave them affirmative status within social space.

In Campanha, schooling developed as the population of Rio das Mortes grew. However, this process happened from the consolidation of a society with a more traditional profile from a racial and gender perspective. Women were present as students in Campanha schools at a considerable rate, but came from households linked to the more traditional family model. From the racial point of view, blacks were present in educational spaces, but on a much smaller scale than white students. So this segment was linked to social patterns that defined more precisely the place of different racial groups.

This can be seen in the record that Ferreira Rezende (1987) presents in his characterization of race relations in the city:

Thus, I met some very respectable families of browns in Campanha, who, by their position and fortune, met all the conditions to belong to the upper class. And indeed, these families were often invited to white balls. Although these families of browns almost never fail to accept the invitation, this does not mean that they went there to dance. In fact, what happened was that they used to appear at these balls only to be mere spectators, or to go there, as was commonly said, to play the role of mere pale lights.

Ferreira Rezende's (1987) record shows that social displacements of the black population were possible, but were accompanied by a demarcation line that placed them in conditions below the segment represented by whites:

The different races did not interchange. Instead, each race and each of its classes never failed to maintain their place. In all races there were gradations, and the boundaries that set them could not be passed without violating the most powerful of all laws - the one based on more or less universal ancient prejudice (Rezende, 1987: 176).

It is not an easy task to justify the differences between Mariana and Campanha. However, these are realities that need analysis that take into account the development of the regions where they were inserted. Thus, we cannot disregard the economic and social processes that promoted the development of Mariana in the eighteenth century and those that led to changes in the captaincy / province, between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, generating a development of the region where Campanha was located.

In this process, it is necessary to highlight the displacement and more intense use of slave labor in the southern region in the nineteenth century, determining a stronger attachment of blacks to slavery and the construction of a racial hierarchy that produced a structure that hindered wider circulation of these individuals. This is a different situation from the one we found in Mariana, where the processes of discrimination did not prevent the movement of this group in different spaces, including elementary schools.

Final Thoughts

The process of elaboration of educational practices in Minas Gerais is permeated by particularities that find different levels of configuration in time and space. Regarding the first aspect, we can say that the issue is evident and receives different levels of investigation of the movement of understanding of the history of education that takes place between the periods of the Colony and the Republic (Carvalho and Faria Filho, 2019).

The same cannot be said about space, which does not always receive due attention in the approaches promoted by the history of education in Minas Gerais, which - in general - tends to naturalize its understanding. The result is analyzes that unify the region based on elements such as captaincy, province, state, counties, cities, etc. These political-administrative terms are often used without questioning their meaning from the spatial point of view, especially in what was defined by Fremont (1980) as lived space, that is, one that is distinguished by an identity defined from the experiences of its subjects.

In this sense, we proposed to demonstrate the specificity of the development process of the region represented by southern Minas Gerais and its particularities in relation to economic, political and social aspects. These particularities are also manifested in education, which, as we saw in Campanha da Princesa, developed into a pattern that accompanied the very development of Rio das Mortes District. In this region we found the highest population density of Minas Gerais in the nineteenth century, a situation that was parallel to the record of individuals in the process of schooling in Campanha, where we found levels much higher than other towns and cities in Minas.

On the other hand, we also found specific traits in relation to the profile of the public that was in elementary schools that presented diversity in its composition, but in different patterns from those we found for other regions, indicating the existence of the profile of a more traditional society.

These elements indicate the importance of incorporating space in the analysis of educational historiography, which reaffirms the need to take this dimension into account when describing the processes of establishing education in Minas Gerais. Analyzes that take into account the historical processes of occupation of the territory represented by Minas will help us to understand the different characteristics of this region and the educational processes that was developed in it. The history of education in Minas Gerais needs to go this way to assume what has been assertively and enigmatically established by Guimarães Rosa (2009, p. 248): Minas Gerais é muitas. São, pelo menos, várias Minas!15

texto em

texto em