Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.19 no.1 Uberlândia jan./abr 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v19n1-2020-10

Artigos

Reading and writing learning among enslaved black people in Brazil: stories of the “unrecorded” 1

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas (Brasil) Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa do CNPq eteperes@gmail.com

This paper analyzes newspapers ads from the first decades of the 19th century to identify where, how, and from whom enslaved men, women, and children learned to read and to write. This research indicates that, in general, priests, ladies, young women from Europe, for example, were the people who taught reading and writing skills to enslaved people, in their own home. Furthermore, this study shows the relation between teaching those first letters and teaching skills used in home chores and in specialized labor, as the ads themselves reveal.

Keywords: Slaves; Reading; Writing

Neste artigo trabalha-se com anúncios de jornais das primeiras décadas do século XIX com o objetivo de identificar onde, como e com quem, homens, mulheres e crianças escravizadas aprendiam a ler e a escrever. A pesquisa indica que, via de regra, nas próprias residências, padres, senhoras, moças vindas da Europa, por exemplo, estavam entre as pessoas que ensinavam escravos e escravas as habilidades da leitura e da escrita. Além disso, um dos resultados do estudo revela a relação entre o ensino das primeiras letras e o ensino de tarefas domésticas e de ofícios especializados, como indicam os próprios anúncios analisados.

Palavras-chave: Escravos; Leitura; Escrita

En este artículo se trabaja con anuncios de periódicos de las primeras décadas del siglo XIX con el objetivo de identificar dónde, cómo y con quien, hombres, mujeres y niños esclavizados aprendían a leer y a escribir. La pesquisa indica que, como regla, en las propias residencias, curas, señoras y señoritas de Europa, por ejemplo, estaban entre las personas que enseñaban esclavos y esclavas las habilidades de la lectura y de la escritura. Además de eso, uno de los resultados del estudio revela la relación entre la enseñanza de las primeras letras, de las tareas domésticas y de oficios especializados, como indican los propios anuncios analizados.

Palabras clave: Esclavos; Lectura; Escritura

Introduction

History always faces a significant obstacle that researchers must overcome - silence about what was kept hidden or silent. About what is not honorable. Garbage is buried, corpses are walled, and everything ceases to exist. We did not see, we do not know, we have never heard, we take it for granted. (FIGUEIREDO, 2015, p. 8).

After a long period of silence, education and instruction of slave population in Brazil has been the focus of relevant studies. Interest for this topic has been growing in Brazil in different knowledge areas2. Despite that, those studies are still insufficient. There is much to be done to identify and understand education and school processes involving slaves in Brazil.

The main purpose of this paper is to contribute to that line of investigation. However, it also has a more specific purpose: to identify early reading and writing learning among slave population (where, how, and from whom enslaved men, women, and children learned how to read and to write). To do that, it starts from some basic questions. The simplest and apparently more obvious one is: did enslaved black men and women learn how to read and to write? Some studies undertaken on their ability to read and write indicate the answer is positive, although the number od literate enslaved people was not very high.

According to Fonseca (2002, p. 11), in 1835 it was determined by law that slaves were not to attend school, which would be reserved for free men. Still according to him, however, by the end of the 1860s, schooling - or something very similar to it - was presented as a fundamental factor in the life of free people and enslaved people alike (FONSECA, 2002, p. 11). In light of that conclusion reached by Fonseca and of evidence from the reduced number of studies on the early 1800s, the main objective of this paper is to analyze data from before 1835.

Therefore, following the first question that led to this study, another one is posed: how did enslaved men and women learn how to read and to write? Where did they learn and who taught them? Which resources were used to teach this population? Those questions will not be completely answered in this paper. However, they are still fundamental for this research, motivated it, and guided data collection.

At the onset, we must stress that the history of reading and writing in Brazil is based on visible subjects and social groups, i.e. population in prestigious positions and with favorable economic, social, and cultural statuses. In other places, however, research on this topic has followed a different path:

In Europe and in the United States, those studies are being combined to another perspective that deals with ‘those who lack literacy’. For example, in Italy researchers study writing by regular people from all time periods; in Portugal, writing by those who were arrested by the inquisition, as well as by those socially under-represented, about whom a whole book was written; in Spain, fools, slaves, women, imprisoned people, and others had their writing analyzed in a series of papers. In Brazil, in the past, ‘those who lack everything’ have been highlighted by historiography on different topics: slave revolts, the world of those who were freed, homeless, street children, vagrants, slaves’ family and love life, etc. As for reading and writing, there is very little work that does that; any research that does, however, combines this topic with racial issues. (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 2. emphasis added).

In light of that, this paper seeks to contribute to studies about teaching in general and specifically about learning and using writing and reading skills by those who were historically excluded and marginalized in Brazil, under the combined perspective mentioned by the author quoted above. In our specific case, thus, this means an effort to identify where, how, from whom enslaved men, women, and children learned to read and to write. There is evidence that they learned at home and at religious contexts, such as from priests, from tutors of their owners’ children (following and listening to classes), from benefactors, etc. For this research, data was collected from newspapers that were published in different Brazilian states and that are available at the Biblioteca Nacional Brazilian Digital Newspaper Library3. That data allows us to reflect on those issues. This paper highlights ads from newspapers from the state of Rio de Janeiro published exclusively during the first three decades of the 19th Century4. This is due to the fact that “we notice Brazilian historiography is timid on its work on the relationship between slaves and former slaves and the lettered world. So far, few studies have looked at the 18th Century and at the first half of the 19th Century” (MORAIS, 2007, p. 497).

Under a perspective of “multiple histories” and considering home education, Oliveira (2005, p. 60) notes, for example:

If in some cases home environments favored slaves’ access to reading and writing, this resulted in different reading and writing skill levels for those slaves. Such history is, thus, multiple, comprised of countless nuances. If research on this issue is ever conducted, it shall reveal not one history, but several, as many as the number of cases analyzed (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 60).

Therefore, this research is a difficult endeavor that will result not in one history, but in multiple single histories of those “unrecorded”: enslaved black men and women in Brazil.

1. Reading and writing learning among slave population

Researchers who focus on the history of education have sought to join the movement of broadening historiography perspectives employed to study slavery and its abolition in Brazil. According to Fonseca (2002, p. 15), this confronts theories that treated slaves as things and categorized them as beings unable to think about the world through their own experiences regardless of meanings imposed by slave owners. This new historiography intents to “recover a world created by slaves within the society that oppressed them and [...] to broaden the understanding about the actions of enslaved black people, attributing a meaning of resistance to activities that were not seen as such before” (FONSECA, 2002, p. 15).

Therefore, recognizing literacy learning and teaching processes, as well as reading and writing practices of enslaved men and women is crucial, albeit notedly difficult from a research standpoint, as it is an effort to write a part of the history of those “unrecorded”:

Formal school education of slaves was completely forbidden in Brazil, and even free black men and women were not authorized to attend classes. This ban was kept throughout the slavery period, even during the second half of the 19th Century when the system was in crisis. Owners and priests who decided to teach slaves how to read and to write went against established rules, and there were few of them. This is why Brazilian slaves were unknown, with no written records. (MATTOSO, 2001, p. 113 apud OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 51, emphasis added).

Still “[...] one can raise the hypothesis that black people did not remain passive regarding reading and writing; for them, those skills represented something positive. They were aware of this, which resulted in those skills being encouraged” (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 62). The argument that enslaved and free black men and women did no remain passive on learning reading and writing is critical for research on this topic. It is fundamental to follow any lead, as indirect as it may seem, to identify actions and practices of enslaved population regarding strategies to learn and teach how to read and write. This includes the hypothesis that even within the group, among themselves, there could be ways of passing on that knowledge. As for strategies within families, the author mentioned above explains that

[...] in 1835, when black men suspected of having taking part in the Malê revolt were interrogated, Ignácio Santana, an elderly freed Nagô, stated that his occupation was to teach his children, one as a woodworker and one at school, and to raise the youngest one. Although it is not clear what exactly the word ‘school’ means in this context, it does not indicate learning a specific trade, as if it were, Ignácio Santana would have named such trade as he did when talking about his oldest child. (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 62-63).

Continuing to identify reading and writing skills among enslaved population, the following argument by Luz (2013, p. 76) based on a study by Karasch (2000) seems quite relevant. He argues some people from Africa who arrived in Rio de Janeiro

[...] had already learned how to speak, read, and write Portuguese in Africa. Others were creole who had learned the language at a Portuguese colony, and there were those who came from regions of Africa where Portuguese vocabulary or the language itself had been incorporated given their long-standing relationship with the Portuguese or with merchants who spoke Portuguese. Therefore, it is completely plausible that some of the literate slaves in Rio de Janeiro had learned how to read and write Portuguese in Africa or from other slaves in the city, who continued to pass on the language from ‘father to child’.

We must recognize, however, how hard it is to find those stories and, at the same time, to determine numbers and percentages of how many black people knew how to read and to write, or either to read or to write, among enslaved population. Data on slave education included in the first official census held in Brazil, in 1872, is shown in Table 1. The census recorded information on that population on the following aspects only: Literate and Illiterate. Keeping in mind the limitations of the census, especially this was the 19th Century, when censuses were just being implemented in Brazil, and that the population being studied was not recognized as such by the rest of society, data is as follows:

Table 1: Literate and illiterate slave population according to the 1872 Census

| Number of people | Literate | % | Illiterate | % | |

| Total | 1,510,806 | 1,403 | 0.09% | 1,509,403 | 99.91% |

| Men | 805,170 | 958 | 0.12% | 804,212 | 99.88% |

| Women | 705,636 | 445 | 0.06% | 705,191 | 99.94% |

Source: BRAZILIAN CENSUS, 1872

If illiteracy rates among general population were high at the time, for enslaved men and women those rates were even higher, as we can see from Table 1. According to Ferraro & Kreidlow (2004), considering the 1872 census, general illiteracy rate in the country was 82.3% for people aged 5 or older, which had not changed by the second census, held in 1890 (82.6%), when Brazil was a young Republic. As shown in Table 1, illiteracy rates among enslaved population was 99.91%. Therefore, those who knew how to read were just 0.09%. Considering men and women separately, rates are not much more significant, as we can see. Therefore, this is another motivation for this study: scientific curiosity to seek to understand who those people were, how they learned to read and to write, and from whom. In light of the very small numbers revealed by the 1872 census of those who knew how to read, we ask: how did this people learn those skills (to read, or even to read and to write in some cases) in such an hostile environment of social exclusion and them not being recognized as human beings? This is an unsettling question, which possibly has many difficult answers. It has not been an easy task to try to answer it.

According to Oliveira (2005, p. 69), there is evidence that explains “why illiteracy was not prevalent in 100% of the slave population”. The author stresses three factors that may help explain that: a) Affectionate relationships between slaves and their owner’s family; b) The degree of specialization needed for some trades, which required knowledge of reading and writing; c) The positive way literacy was perceived among black men and women and the role of black brotherhoods (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 69).

All hypotheses that explain literacy among enslaved population - regardless of its rate - are deemed plausible and significant. Much of the evidence may be only circumstantial, but it still should - and could - be considered and followed up, especially in this necessary effort of writing “the stories of the unrecorded”. In light of that, next we highlight some data collected in our research, which, at times and indirectly, allow us to reflect on the question posed on reading and writing learning among enslaved population: where, how, and from whom did enslaved men and woman in Brazil learn how to read and to write?

2. Evidence of reading and writing abilities among slave population: announcements of escapes and slave sell/purchase ads

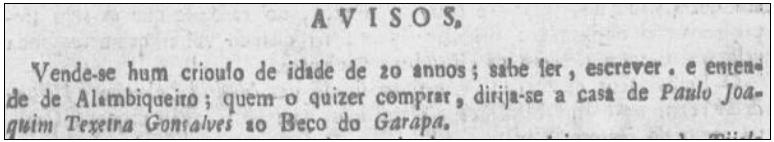

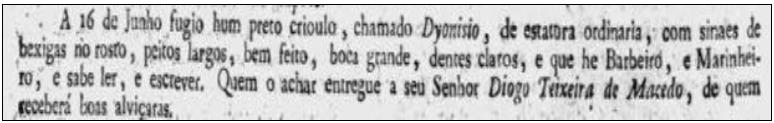

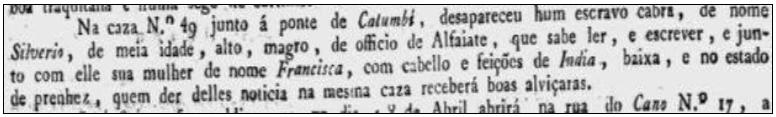

There are few situations in which there are records for the “unrecorded”, and they all refer to persons with no name and no identity. For enslaved people, this was what often happened. In general, when they appeared on records such as newspapers ads, they were reduced to one or more characteristics linked to their ethnicity or race: black, mixed-race, creole, slave, with the facial features of an indigenous woman, impregnated, ample breasts, large mouth, white teeth, with scars, and other. This was revealed by newspapers data collected during the research5. In other cases, those people are identified by their first name alongside their features and skills: Dyonisio, Silverio, Francisca, for example. In Images 1, 2, 3, and 4 below, we present examples of sales ads or notices in which they were wanted for having escaped:

[Notice. One 20-year-old creole for sale. He knows how to read, to write, and to operate stills. Whomever wishes to purchase him, please go to the house of Paulo Joaquim Texeira Gonçalves at Garapa Alley.]

[Notice. Joaquim Malaquias da Silva, from Fonte dos Padres Street, no. 44, wishes to sell a black person who knows how to read, to write, and to count well.]

[On June 16, a creole black man named Dyonisio ran away. He is average height and has pockmarks on his face. He is broad shouldered, strong, with a large mouth and white teeth. He is a barber and a sailor and knows how to read and to write. Whomever finds him, please return him to his owner, Diogo Teixeira de Macedo, who shall pay a handsome reward.]

[At house no. 49 by Calumbi Bridge, a mixed-raced slave called Silverio disappeared. He is middle-aged, tall, thin and works as a tailor. He knows how to read and to write. His wife, Francisca, also disappeared with him. She has the hair and the facial features of an indigenous woman. She is short and impregnated. Whomever has any information on them, please present it at that house, and a handsome reward shall be paid.]

As we can see, what all ads above have in common is the fact that they include information about the slave being able to read and to write or, in one instance, being able to read, to write, and to count. Furthermore, we notice some of them had specialized trades: still operator, barber, sailor, tailor. Considering another study about specialized trades in the Neutral Municipality, Oliveira (2005, p. 61) states that

[...] since the arrival of the royal family, with the growth of the cities and new business opportunities, small businesspeople were interested in educating their slaves for certain tasks, as they could increase their revenue.

On the subject matter of this study, the author states that there were

[...] schools specialized in training slaves, which offered them not only skills required for their trades, but also taught them reading, writing, and counting. Therefore [...], learning certain skills depended on owners’ will and resources available to train slaves. Among slaves, those who specialized in a trade were a minority, which means that if there was a relationship between literacy and specialized trades in Court, there were few slaves who learned how to read, to write, and to count due to learning said trade (OLIVEIRA, 2005, p. 61).

One cannot assert, then, that the relationship between specialized trades and the number of literate slaves was very expressive. Furthermore, Oliveira (2006, p. 61) also reminds us that the majority of slaves were employed in tasks that did not require any specialization. Determining from whom, when, where, and how slaves learned how to read and to write in either context - i.e., whether or not they performed any specialized trade - is a research challenge we have been trying to overcome.

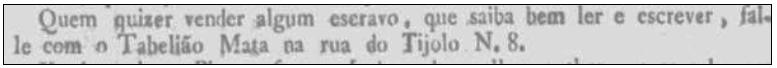

Among the ads analyzed, we also found some that sought slaves who knew how to read and to write. This not only shows that there were those among that population who mastered those skills, but also that knowing how to read and to write could help them achieve less severe and adverse positions and conditions than those faced in farms, sugar mills, and charqueadas, for example. Image 5 shows an ad seeking a slave who knows how to read and to write well. The fact that the ad mentions that the party interested in selling should contact Notary Mata may indicate some specialized service at the Notary’s Office itself. Those are just assumptions, albeit important ones to reflect on the questions posed:

[Whomever wishes to sell a slave who knows how to read and to write well, please contact Notary Mata at Tijolo Street, no. 8.]

As we can see from this section, there is data evidencing reading and writing skills among enslaved population, although they are rare and insufficient for reaching more general conclusions. Beyond that, other questions were posed by this research. Next, we try to answer one of them, at least in part.

3. Who taught enslaved people how to read and to write?

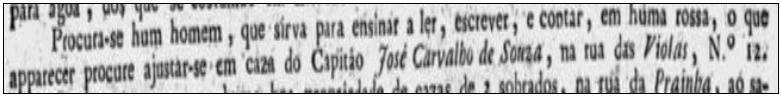

First, we highlight that the search for men and women who taught how to read and to write was somewhat common in the early 1800s. That indicates how important homeschooling was in that context. It could take place either at the learners’ home or at the tutors’ home. Education could include teaching how to read and to write as well as other skills. The following ads in Images 6 and 7 are examples of that:

[A man is wanted to teach reading, writing, and counting at a farm. Whomever is interested please present himself at the house of Captain José Carvalho de Souza at Violas Street, no. 12].

[Anna Maria Roza lets it be known to all that she is willing to teach girls, even little black girls, how to sew and embroider, and if they want, to read and to write. Whomever is interested may find her at Alecrim Street, no. 111, to negotiate the price.]

As we can see, Image 7 is an ad published by a woman offering to teach girls domestic skills, such as sewing or embroidering, and if they want, to teach them how to read and to write, including little black girls. Assuming that even slave girls were taken to tutors’ homes at times to study does not seem that unlikely. Therefore, the question of who taught enslaved people how to read and to write could have multiple and different answers according to different life stories.

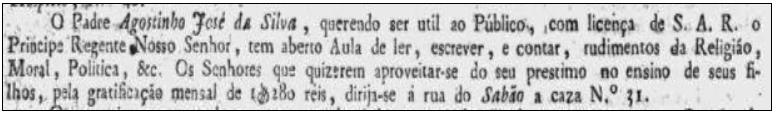

Priests also offered to teach how to read, to write, and to count. Although it does not mention its intended audience (albeit the fact it refers to paid classes is an indication), the following ad in Image 8, together with other sources and other data, strengthens the evidence that priests who lived in Brazil also served as teachers:

[Priest Agostinho José da Silva, who wishes to be of use to the public, under authorization of His Royal Highness Our Lord the Prince Regent, offers classes on how to read, to write, and to count, as well as basic Religion, Morals, Politics, etc. Gentlemen wishing their children to attend those classes in exchange for the monthly compensation of 1,280 réis shall visit house no. 31 at Sabão Street.]

There is evidence that priests also taught enslaved men and woman how to read and to write, but there is no way of telling if this was the case for Agostinho José da Silva.

One known case of a literate slave who supposedly learned how to read and to write from Jesuit priests was Esperança Garcia. There is not much information available about enslaved black woman Esperança Garcia, such as where and when she was born. However, we do know she lived during the 18th Century in the region where today the state of Piauí is located, at a time when Maranhão and Piauí were at the same captaincy (SOUZA, 2015; ROSA, 2012). She became known for having written a letter6 to the governor of Piauí, Gonçalo Lourenço Botelho de Castro, demanding her right to live close to her husband and her children and criticizing slave labor. According to Souza (2015, p. 3), “Esperança Garcia’s ‘Letter’ is a real portrait of the human experience of black men and woman who lived through the hell of slavery”. Furthermore, still according to that author, her letters represent slave resistance and “breaks down racial stereotypes about the ‘natural’ submission of black slaves” (SOUZA, 2015, p. 4).

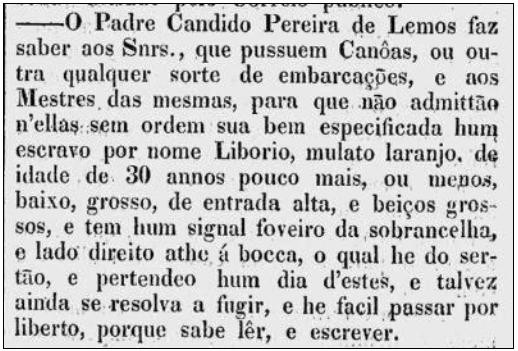

In a newspaper ad published in 1833, another priest, Candido Pereira de Lemos, warned vessel commanders and canoemen not to admit slave Liborio into their boats without his express order. The fact that Liborio knew how to read and to write would make his escape easier, as he could impersonate a freed slave:

[Priest Candido Pereira de Lemos lets it be known to all gentlemen who own canoes or any other sort of vessel and their Captains not to admit into their vessels without his express orders a slave named Liborio, who is a mixed-race slave, around 30 years of age, short, thick, with bald spots and thick lips. He has a white patch in his skin extending from his eyebrows, running down the right side of his face, to his mouth. He is from the rural area and recently has attempted - and might still attempt - to escape. He can easily impersonate a freed slave, as he knows how to read and to write.]

With that ad we restress that priests themselves owned slaves, as historiography has already shown. The assumption that they taught their slaves how to read, to write, and/or to count is not farfetched. We can also hypothesize that enslaved men and women learned by observing and paying attention to lessons taught to other children and to young white and rich people.

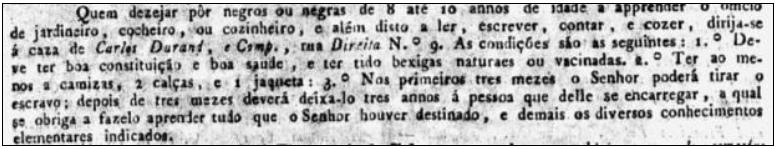

In ads, however, there is explicit evidence that enslaved children were taught how to read and to write, such as in the following case:

[Whomever wishes black men or women aged 8 to 10 to learn the trades of gardener, coachman, or cook; and furthermore, to read, to write, to count, and to sew, please find Carlos Durand Inc. at Direita Street, no. 9. Conditions are as follows: 1. To have a good build and to be on good health; and to have had smallpox naturally or to have been vaccinated against it. 2. To have at least 2 shirts, 2 pants, and 1 jacket. 3. During the first three months, the owner may take his slaves back. After three months, the owner shall leave them under the responsibility of the person in charge of them for three years. Such person commits to teach them everything the owner has requested, as well as all other basic knowledge required.]

The contents of this 1819 ad are very significant for our research due to the questions we posed. Besides indicating a gender issue - black men and women - and the enslaved status of learners, it gives us another important piece of information: teaching of reading and writing, both for boys and for girls, was linked to teaching of a specialized trade. In this case, gardener, coachman, cook, seamstress. The facilities and the persons in charge of Carlos Durand Inc. imposed some requirements for owners who wished to trust them with trainees: proper health and clothing, as well as the time required for learning, i.e. owners had three months to take theirs slaves back, otherwise, after that period, they had to keep them there for at least three years. Three years was a relatively long time for learning. Beyond the required skills for each trade, reading and writing skills could also be adequately gained during this time.

Still on trade learning by slaves, we must also point out that their work “resulted in easy and guaranteed profits for their owners. That is why they taught them one or more trades and explored them as much as possible, living off their work” (LUZ, 2013, p. 75), either directly putting slaves to work or leasing them to third parties. However, we must also keep in mind that mastery of specialized professional skills and work away from the eyes of their owners allowed slaves to “move more ‘freely’ through the streets of the city. They could choose and establish new friendships, families, or professional relationships, almost reaching the same status of those who were free” (LUZ, 2013, p. 75). Perhaps during those times when they moved more “freely” and built new relationships, they also learned how to read and to write; perhaps when they learned a trade, they also learned how to read and to write at the same time. Although Luz (2013, p. 76) states there is no evidence that private vocational or trade “schools” that accepted slaves also taught them how to read and to write, ads shown here point to that possibility. Offers from people willing to teach both trade skills and reading and writing skills were common in newspapers we analyzed. Examples shown here clearly refer to private classes. However, considering this was how Brazilian education functioned in the late 1700s and early 1800s, it makes sense to think of those private classes as the standard for education - and there is evidence of simultaneous teaching of trades and reading and writing in them.

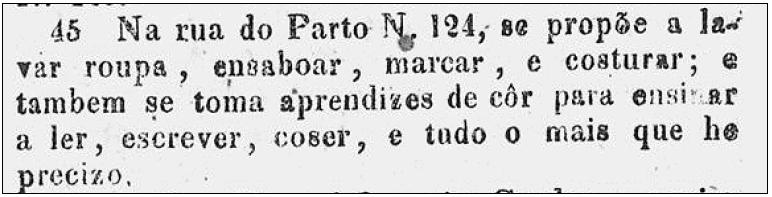

Therefore, next we present another example of said relationship between teaching how to read and to write and teaching home and trade skills:

[45. At Parto Street, no. 124, we wash clothes, iron them, embroider them, and sew. We also accept learners of color to teach them how to read, to write, to sew, and whatever else is requested.]

In 1826, at Parto Street, in Rio de Janeiro, there might have been at least one slave among the learners of color. Furthermore, it would not be a leap to assert that teaching how to do laundry, to clean, to sew, were domestic tasks taught by women to other women. In this context, we may infer that women taught slave girls how to read and to write. Other data worthy of attention were found during the research regarding gender issues, especially on slave girls. That is what we analyze next.

3. Did women teach little black girls how to read?

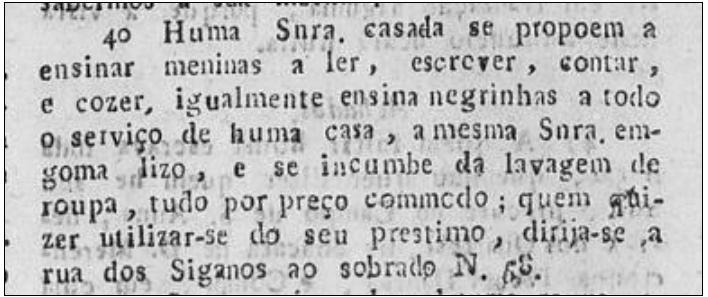

As we pointed out with the case of Anna Maria Roza in the ad shown in Image 7 above, ladies7 offered to teach girls domestic tasks or trades. In the following ad, shown in Image 12, the offeror is identified by gender and marital status, two relevant social markers in the society of the 1800s: it is a married lady who offered to teach girls, even little black girls:

[40. A married lady offers to teach girls how to read, to write, to count, and to sew. She also teaches little black girls all home services. That same lady irons and washes clothes, all for a fair price. Whomever wishes to employ her services, please go to house no. 58 on Siganos Street].

It is not possible to affirm from the ad if the married lady from house 58 at Siganos Street, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1822 - who taught girls how to read, to write, to count, and to sew, and little black girls all home tasks, and who did laundry - also taught slaves. However, that would not be an unfounded assumption, especially considering the following ads.

Frederica, Carlota, and Candida - who seem to be three sisters who had just arrived from Europe - published the following ad in 1816:

[The undersigned, having recently arrived from Europe, inform everyone that they are ready and qualified to teach how to read and to write, to count, to iron, to sew, to embroider, to frizz both fabric and twine, to make silk socks, plain or embroidered, and gloves, all for a fair price. Whomever wishes to have girls and slaves taught may look for the offerors at Santa Luzia Street, no. 6, the house of Mr. Joze Antonio da Costa e Silva. Likewise, they inform they make all kinds of dresses swiftly, neatly, and tastefully. Whomever wishes to employ that service may also look for them at that same house. Caxias, March 26, 1816. Frederica Augusta da Costa e Silva, Carlota Guilhermina da Costa e Silva, Candida Jozephina da Costa e Silva.]

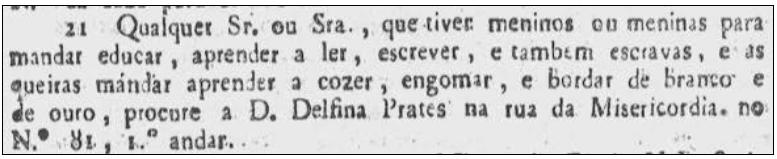

Frederica, Carlota, and Candida, whose last names were all Costa e Silva, were probably the daughters of Joze Antonio da Costa e Silva. They taught girls - even slaves - how to read, to write, to count, to iron, to sew, to embroider, to make socks and gloves at their own home. Therefore, this was an exclusively feminine setting: a task performed by women for women learners, both free and enslaved. That was Brazilian reality in the early 1800s. Lady Delfina Prates did the same in 1821, also in Rio de Janeiro: teaching boys and girls, as well as slaves:

[21. Any lady or gentlemen who has any boys or girls they wish to have educated on how to read and to write, as well as slave girls they wish to have learn how to sew, iron, and embroider in white and gold, look for Lady Delfina Prates at Misericórdia Street, no. 81, first floor.]

As we can see, Delfina Prates explicitly offered to teach slave girls domestic tasks such as sewing, embroidering, and ironing. She also offered to teach boys and girls how to read and to write. It makes sense to consider that during those classes, domestic skills and reading and writing skills were taught both to free and enslaved girls.

In general, authors who research enslaved population education, schooling and/or literacy recognize how difficult it is to know how and where they learned to read and to write. This is even more difficult when we deal with enslaved women. Luz (2013, p. 77) states that “it is hard to know exactly how they learned how to read and to write, especially women, in a largely illiterate society”. Ads collected during this research and shown in this paper present important data to establish a clearer picture of reading and writing learning among enslaved black men and women in Brazil. This is still a very incomplete and limited picture that can and must gradually be completed - perhaps not fully, as we are dealing with those about which no written records were kept and because it is an illusion to think of a complete history, but rather, a picture comprising several and multiple stories.

Finally, we point out that just like for other locations, times, and social groups, mastery of reading and writing skills among enslaved population existed at different levels and abilities. There were probably those who read only sparse letters or syllables, while others read a few words and simple phrases and there were those who were fluent and read newspapers, books, pamphlets, etc. As for writing, there were those who only signed their own names, and those who could write notes, letters, essays, news stories, petitions, etc. Those differences also make up the different stories from that population and its relationship to written culture. Stories that must be told, as we must remember that History shall face the great challenge of overcoming silences (FIGUEIREDO, 2015).

Final remarks

As we saw from newspapers ads, priests and ladies - possibly benefactors, young ladies coming from Europe, such as the Costa e Silva sisters, for example - were among those who taught enslaved men and women how to read and to write. Classes could take place at the homes of those teaching and of learners alike.

As mentioned above, according to Fonseca (2002), in 1835 it was legally determined that slaves could not attend school. Data presented in this study are all prior to that date, as they were published during the first three decades of the 19th Century. We could then pose the following questions: did this legislation detain an ongoing process of teaching and schooling enslaved black men and women? Before that date, were there more people willing to teach enslaved population? During the early 1800s (and possibly before that), did this teaching allow a small number of slaves to become literate and to transfer their knowledge to others? It is not unthinkable that slaves - men, women, and children - shared knowledge about how to read and to write with other slaves. Possibly, learning networks among enslaved people were in place where they lived and were developed during the little spare time they had. Once again, for now, these are just arguments and questions to encourage thought; they are just hypotheses and possibilities for research.

One of the main results from this study is showing the relationship between teaching how to read and to write and teaching home and trade skills. We consider this to be an important research clue: ads show that the same people who were willing to teach specialized trades and skills also taught free and enslaved children how to read and to write. It is difficult to conceive each skillset was taught separately. Therefore, we argue they were taught simultaneously.

Finally, we must think about the contradiction of the slave system regarding their education. If, on one hand, owning an enslaved man or woman who knew how to read and to write could benefit the owner, as it added value in work relationships and sales agreements, on the other hand, it could pose a threat to established order, control, and hierarchy. It was possible literate enslaved men and women posed a real threat against owners and the slave system. In the history of highly unequal and unfair systems and societies, learning how to read and to write has always been a way to empower the underprivileged. Among enslaved people, mastering the written word was a strategy to resist and to fight, even though not many of them had access to it. Referring specifically to enslaved women, Angela Davis (2016, p. 34) argues that “resistance was often more subtle than revolts, escapes and sabotage. It involved, for example, the clandestine [or unauthorized] acquisition of reading and writing skills and the imparting of this knowledge to others”.

REFERENCES

AMANTINO, Márcia. Os escravos fugitivos em Minas Gerais e os anúncios do Jornal "O Universal"- 1825 a 1832. Locus. Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.12, n.2, p. 59-74, 2006. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Marialva. Escravos letrados: uma página (quase) esquecida. Revista da Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação, v.12, n.1, 2009, p.1-19. https://doi.org/10.30962/ec.v12i1.371 [ Links ]

BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara. A educação dos escravos e libertos no Brasil: vestígios esparsos do domínio do ler, escrever e contar (Séculos XVI a XIX). Cadernos de História da Educação, v. 15, n. 2, 2016, p. 743-768. https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v15n2-2016-15 [ Links ]

DAVIS, Angela. Mulheres, raça e classe. São Paulo, Boitempo Editorial, 2016. [ Links ]

FERRARO, Alceu R.; KREIDLOW, Daniel. Analfabetismo no Brasil: configuração e gênese das desigualdades regionais. Educação e Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 29, n.2, p. 179-200, 2004. [ Links ]

FIGUEIREDO, Isabela. Cadernos de memórias coloniais. Lisboa, Editorial Caminho, S.A., 2015. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Marcus Vinicius. A educação dos negros: uma nova face do processo de abolição do trabalho escravo. Bragança Paulista: Editora da Universidade São Francisco, 2002. [ Links ]

FREYRE, Gilberto. O Escravo nos anúncios de jornais brasileiros do século XIX: tentativa de interpretação antropológica, através de anúncios de jornais, de característicos de personalidade e de deformações de corpo de negros ou mestiços, fugidos ou expostos à venda, como escravos, no Brasil do século passado. Recife: Imprensa Universitária, 1963. [ Links ]

LUZ, Itacir Marques. Alfabetização e escolarização de trabalhadores negros no Recife oitocentista: perfis e possibilidades. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação. v.13. n.1 [31]. 2013, p. 69-94. https://doi.org/10.4322/rbhe.2013.015 [ Links ]

MORAIS, Christianni Cardoso. Ler e escrever: habilidades de escravos e forros? Comarca do Rio das Mortes, Minas Gerais, 1731-1850. Revista Brasileira de Educação v. 12 n. 36 set./dez. 2007. pp. 493-504. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782007000300008 [ Links ]

MOYSÉS, Sarita M. Affonso Leitura e apropriação de textos por escravos e libertos no Brasil do século XIX. In: Revista de Ciência e Educação - Educação e Sociedade. São Paulo: Papirus, n.48, agosto/1994. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Klebson. Negros e escrita no Brasil do século XIX: sócio-história, edição filológica de documentos e estudo linguístico. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras e Linguística (Doutorado em Letras). Salvador, Bahia, 2005. 1198p; 2v. http://www.repositorio.ufba.br/ri/handle/ri/12042. Acesso em 15 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

ORO, Ari. Religiões Afro-Brasileiras do Rio Grande do Sul: Passado e Presente Estudos Afro-asiático. v.24, n.2, Rio de Janeiro, 2002. pp. 345-384. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-546X2002000200006 [ Links ]

RECENSEAMENTO DO BRAZIL EM 1872. Disponível em https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv25477_v1_br.pdf. Acesso em 01 jul. 2019. [ Links ]

ROSA Sonia. Quando a escrava Esperança Garcia escreveu uma carta. Ilustração: Luciana Justiniani Hees. Rio de Janeiro: Pallas Editora, 2012. [ Links ]

SILVA, Alexandra Lima da. Flores de Ébano: a educação em trajetórias de escravizadas e libertas. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa (Auto)Biográfica, Salvador, v.4, n.10, p.299-311 jan./abr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.31892/rbpab2525-426X.2019.v04.n10.p299-311 [ Links ]

SOUZA, Elio Ferreira de. A “carta” da escrava Esperança Garcia do Piauí: uma narrativa precursora da literatura afro-brasileira. 2015. Disponível em http://www.abralic.org.br/anais/arquivos/2015_1455937376.pdf. Acesso em 15 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia M. Retrato em branco e negro: jornais, escravos e cidadãos em São Paulo no final do século XIX. São Paulo: Cia das Letras, 1987. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, Maria Celi C. A casa e os seus mestres. Rio de Janeiro: Gryphus, 2005. [ Links ]

VILLELA, Heloísa de O. O Mestre Escola e a Professora. In: LOPES, Eliane et. al. 500 anos de Educação no Brasil. 2ª ed. Autêntica. Belo Horizonte, 2000. [ Links ]

WISSENBACH, Maria Cristina C. Cartas, procurações, escapulários e patuás: os múltiplos significados da escrita entre escravos e forros na sociedade oitocentista. In: Revista Brasileira de História da Educação. São Paulo: Autores Associados, n.4, jul./dez., 2002. p.103-122. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

A FEDERAÇÃO. Órgão do Partido Republicano. Sabbado, 24 de outubro de 1885, Nº 242, p. 02, Porto Alegre, 1885. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 05 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Sexta feira, 2 de novembro de 1821, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1821. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 05 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Terça feira, 28 de maio de 1822, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1822. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 05 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Segunda Feira, 12 de junho de 1826, N. 09, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1826. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 23 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Quarta feira, 15 de julho de 1812, Nº 57, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1812. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 22 mar. 2017. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Quarta feira, 8 de junho de 1814, Nº 46, p. 02. Rio de Janeiro, 1814. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 03 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Sabbado, 22 de julho, 1815, Nº 58, p. 02. Rio de Janeiro, 1815. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 03 jun 2017. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Quarta feira, 18 de setembro de 1819, Nº 74, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1819. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 22 mar. 2017. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Sabbado, 1º de abril de 1820, s/n, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1820. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 22 mar. 2017. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Impressão Regia. Sabbado, 07 de abril de 1821, Nº 28, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1821. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 22 mar. 2017. [ Links ]

IDADE D’OURO DO BRAZIL. Bahia. Typographia de Manoel Antonio da Silva Serva. Terça feira, 3 de agosto de 1813, Nº 62, p. 02. Bahia, 1813. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 03 jun 2017. [ Links ]

IDADE D’OURO DO BRAZIL. Bahia. Typographia de Manoel Antonio da Silva Serva. Sexta feira, 21 de outubro de 1814. Nº LXXXVV. Bahia, 1814. Acesso em 22 mar. 2017. [ Links ]

IDADE D’OURO DO BRAZIL. Bahia. Typographia de Manoel Antonio da Silva Serva. Terça feira, 14 de abril de 1818, Nº 30, p. 02. Bahia, 1818. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 03 jun 2017. [ Links ]

IDADE D’OURO DO BRAZIL. Bahia. Typographia de Manoel Antonio da Silva Serva. Sexta feira, 1º de janeiro de 1819, Nº 01, p. 02. Bahia, 1819. Disponível em Biblioteca Nacional. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira: http://memoria.bn.br/hdb/periodo.aspx. Acesso em 03 jun 2017. [ Links ]

JORNAL CAXIENSE, Segunda feira, 11 de mayo de1816, N. 10, p. 03, Rio de Janeiro, 1816. [ Links ]

O PUBLICADOR OFICIAL, Sabbado,18 de maio de 1833, N. 160, p. 02, Rio de Janeiro, 1833. [ Links ]

1The original paper in Brazilian Portuguese was translated into English by Leonardo A. Peres, holder of a Post-Graduate Diploma in Translation Studies from the Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, professional translator. E-mail: leonardo@lptrad.com

2Among others, see Moysés (1994); Oro (2002); Wissenbach (2002); Oliveira (2005); Morais (2007); Barbosa (2009); Luz (2013); Bastos (2016).

4According to Amantino (2006), Gilberto Freyre was the first to use, in the 1930s, newspaper ads in slavery historiography. Conclusions from his studies were published in 1963 as a book, entitled O escravo nos anúncios de jornais brasileiros do século XIX (“Slaves in Brazilian newspapers ads in the 19th Century”). Therefore, still according to Amantino (2006, p. 60), although subject to some criticism, researchers have followed in Freyre’s footsteps and some research was conducted and papers were published on the daily life of slaves and on slave escapes using newspaper ads published at different places and different times of the 19th Century as sources. Another important book on this issues is Lilia M. Schwarcz’ Retrato em branco e negro: jornais, escravos e cidadãos em São Paulo no final do século XIX (“Portrait in black and white: newspapers, slaves, and citizens in São Paulo during the late 19th Century”), published in 1987.

5[...] “as those ads were used as means of identifying escaped slaves, their owners had to provide information that would allow their capture” (AMANTINO, 2006, p. 72).

6The letter is dated September 6, 1770. A copy was found by historian Luiz Mott in 1979 at the Public Archives of the State of Piauí. The original is supposedly in Portugal, in the records of Brazilian colonial history (SOUZA, 2015; ROSA, 2012).

7Ladies who taught people how to read and to write might not have been exactly “teachers”. All ads collected during the research were published before the first Normal School was founded in Brazil, in Niterói, in 1835, for example. Besides, at that time, access to public schooling was still very limited. In general, schools were basically public and private classes at a teacher’s home or at another domestic space, usually leased and kept by a teacher (LUZ, 2013). Schools and classes during the imperial era in Brazil, especially in its beginning, were inherited from the colonial period - regal schools or public literacy classes - as pointed out by Faria Filho (1999). On Normal Schools and the history of teacher education in Brazil, see Villela (2000). On domestic schooling and teaching in Brazil during the 1800s, see especially Vasconcelos (2005).

Received: June 30, 2019; Accepted: August 30, 2019

texto em

texto em