Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.19 no.1 Uberlândia jan./abr 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v19n1-2020-12

Artigos

“A Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário” Another way of doing politics: on the reform of school services (1924-1935) 1

1Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Portugal) band.lisboa@gmail.com

This article is part of a project about schools and experiences of reference in Portugal in the 20th century. It focuses on the study of Voz do Operário, an institution that developed educational activities for the lower classes in an associative context. We opted for a descriptive presentation with the intention of arguing that the adoption and application of an educational model - inspired by the New Education (Educação Nova) and aimed at a specific audience - was based in a socio-political strategy, which emerged both from the historical conditions of workers’ associativism in the first half of the 20th century, and from the situation Portugal was living due to the crisis of the First Republic, which would lead to the the New State (Estado Novo). In the article, we explain the reform process which was undertaken in the educational services of Voz do Operário between 1924 and 1935. Beforehand, we present a brief history of Portuguese society from the end of the 19th century until the 1950s, to give a representation of the worker's association in its dimension, activity and social meaning.

Keywords: Worker’s Associativism; New Education; Portugal

Este artigo insere-se num projeto sobre Escolas e experiências de referência em Portugal no século XX e centra-se no estudo de uma instituição que desenvolve atividades educativas num quadro associativo e para as classes populares. Optámos por uma apresentação descritiva com a intenção de argumentar que a adoção e aplicação de um modelo educativo, inspirado na Educação Nova e conformado a um público específico, assentou numa estratégia sociopolítica, emergente das condições históricas do associativismo operário na primeira metade do século XX e da situação vivida no País com a crise da Primeira República, que desembocou no Estado Novo. No artigo explanamos o processo de reforma dos serviços escolares da Voz do Operário entre 1924-1935, não sem antes apresentarmos uma história sumária da Sociedade, desde o fim do século XIX até à década de 1950, com o objetivo de representar a associação na sua dimensão, atividade e significado social.

Palavras-chave: Associativismo operário; Educação Nova; Portugal

Este artículo es parte de un proyecto de investigación sobre el tema Itinerarios de innovación pedagógica: escuelas y experiencias de referencia en Portugal en el siglo XX. Se centra en el estudio de una institución que desarrolló actividades educativas en un marco asociativo dirigido a las clases populares. A través de la descripción de esta institución argumentamos que la adopción y aplicación de un modelo educativo, inspirado en la Escuela Nueva y dirigido a un público específico, se basó en una estrategia sociopolítica surgida de las condiciones históricas del asociacionismo obrero en la primera mitad del siglo XX, así como de la situación vivida en el país con la crisis de la Primera República y el advenimiento del Estado Novo. En el artículo exploramos el proceso de reforma de los servicios escolares de la Voz do Operário [Voz del Obrero] desde 1924 hasta 1935, incluyendo previamente una historia sucinta de la Sociedad de Instrucción y Beneficência desde finales del siglo XIX hasta la década de 1950. Con ello pretendemos mostrar a la asociación en su dimensión, actividad e importancia social.

Palabras clave: Asociacionismo obrero; Escuela Nueva; Portugal

Introduction

The association, Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário, is at the heart of this paper. It was founded in the last decade of the 19th century and has carried out its activity, uninterruptedly, since then up to today. Its action was diffused by its headquarters, in the neighbourhood of Graça, Lisbon, where it was housed from 1924, in the street already called A Voz do Operário [Voice of the Worker], and in the building whose construction it had commissioned to be a large “Casa dos Trabalhadores” [Workers House]. Yet under the constancy of action and a long-lived trajectory, multiple interwoven problems have been revived, which are of relevance for the knowledge and interpretation of this institution. Its trajectory is not linear or without tension, struggles and commitment, regardless of the angles adopted for its observation: that of the associative movement; of educational experiences; and that of the types of social welfare.

The research which gave rise to this paper is part of a broader project, namely INOVAR, which brings together several research groups belonging to different Portuguese universities, whose work focuses on the study of experimental, innovative and alternative education models. To this end, a number of school institutions and pedagogical experiences that have taken shape in our contemporary society and fall under the afore-mentioned criteria were selected.

In the case of A Voz do Operário, the analysis is not dissociated by the angle of the curriculum and educational practices (one of the intervention strands of the association), as might have been expected, but rather a dynamic articulation is established at its centre among: the association, as a form of organisation, with decision-making processes conferred upon a general assembly of members; education, seeking to identify curricular options in relation to the educational goals and how an innovative pedagogical model was, or was not convoked; and social welfare, particularly in the analysis of the types of school support devised to facilitate access to education.

In modern, liberal, industrialised and urban societies, new sociability practices have emerged which are expressed through associativism, « forms of organization of interests and civic participation of the new political order» (Lousada 2017, 97). A Voz do Operário participated in this movement which was particularly active in the late 19th century and in the First Republic. Within a universe composed of different types of associations (educational, scientific, cultural, mutual and professional or class) linked to ideological and political trends, A Voz do Operário was part of an associativism that defended the interests of professional worker groups, from a class perspective, which although not politically assumed, was where socialist, anarchist, syndicalist and Republican sensitivity and activism converged. Amongst all of them, there were members who belonged to the Freemason organisation. Within the scope of defence of class interests, whether as a form of awareness raising of social phenomena, as a strategy to combat illiteracy or for access to schooling, or even as the professional qualification of the worker, education emerged as an investment on the part of associations, based on types of social support. These are the elements that frame the research. As for the chronological period, the years between 1924/25 and 1935, coinciding with the period of the end of the First Republic and beginning of the Estado Novo were chosen, a time when the debate around the reform of educational services and the design of a pedagogical curriculum for the educational structure of the Association [Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário] were configured under the premises of the project. As will be seen, this period was characterised by a bubbling of ideas and experiences taken from Educação Nova [New Education], which mobilized worker organisations, republican and libertarian popular educational institutions, educational and teacher associations, governmental and municipal initiatives that contaminated the educational project of the Association, in an original synthesis, as it was controlled by a workers’ association with a sense of social transformation. The analysis extends up to the early 1950s, so as to examine the application of the curriculum and approved regulations within a new framework of state regulation of the institution.

Institutional chronicles and academic narratives

At the turn of the decade from 1920 to 1930, A Voz do Operário was preparing to celebrate its 50th anniversary with a particularly heedful programme of celebrations. In acknowledgement of the fact that the Association did not have a written history, it was decided in the General Assembly of 1929, that a monograph would be written. It was the aim of its Board of Administration to go beyond the occasional notes, of a memoirist nature, and based on oral tradition, generally produced in speeches or articles published in the journal of the Association to celebrate its anniversary, to invest in historical research, « based on an in-depth study of the minutes, journal collection, correspondence and documents in its archive ». In other words, research based on documental sources «from which the historical truth would spring forth» on «the greatest accomplishment of Portuguese workers» (Santos 1938, 97), would take precedence over oral tradition, adulterated by the passage of time.

This initiative was thwarted. However, the administration of 1930-1931 took it up again, and the then president of the supervisory board, Raúl Esteves dos Santos3, was entrusted with the study, the writing and dissemination of the history of A Voz do Operário: to this end, he took home the «book of minutes of the Administrative Committee, Supervisory Board and General Assembly, in addition to any other documents that might provide enlightenment and the voluminous journal collection » (Santos 1938, 98). Between 1931and 1944, he never stopped writing and producing texts on the history of the Association4.

Raúl Esteves dos Santos was its institutional and official chronicler. He established facts and characterised periods, he identified protagonists (Esteves 1936b), enlightened difficulties and combats and referenced documents proving the situations described. For the more recent phases in the life of the Association, particularly from 1925 onwards, Raúl Esteves dos Santos included his own experience in the historical chronicle, related to the administration of the Association with a programme of action set on revitalizing A Voz do Operário (Esteves 1933b). With the recovery of memory and the construction of a history of the work accomplished by workers for workers, in the name of social justice and progress, the identity of A Voz do Operário was substantiated with a powerful sense of image: Catedral do Bem, Colmeia, Seara de Luz e Epopeia dos Humildes.5

Interpretation of the history of the association was naturally guided by the institution itself, and by one of its own, with positions tied to the defence of workers’ associativism and the ability of the workers to take leadership, in a discourse sown with romanticism. This romanticism became increasingly more accentuated the further back the author went in the history of the Association (to the times of its foundation). All these texts were published, the majority of them under A Voz do Operário, and actually assumed themselves as «the greatest and best propaganda instruments» of the Association (Brocas, 1938, 34). Effectively, in order to maintain its programme and activities, especially when the association’s population began to decrease (1930s), it had to attract members, justify the increased subscription cost and seek public and private subsidies.

Considering how the information is organised in the diachrony, from its foundation up to “its” present - basically the late 1930s, Raúl Esteves dos Santos focuses on four distinct periods in the history of the Association.

The founding period - 1879-1883: restricted to the creation of the journal by the tobacco workers and the overcoming of the first financing crisis, with the constitution of the Cooperative, and the first battle with the other professional classes for control of the journal and the association.

The second period - 1883-1890: corresponding to the construction of the foundations of the future Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário. After discovery of the «elixir of long life» (Santos 1932 a, 27), with the decision taken by the association to provide support for the funerals of its members - a measure that guaranteed the rapid growth of the associative population6 - A Voz do Operário launched its programme for the creation of schools for its members.

The third period - 1890-1924/25: limited to the period between the publication of the statutes of the Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência and the intervention of the Administrative and Inquiry Committee, appointed by the Civil Governor of Lisbon. This period corresponds to the expansionist phase of the association, in members and schools, serving to project the Association at a social level so that it enjoyed legitimacy on the part of the monarchic governments and the Republican State, and acknowledgement on the part of political figures, intellectuals, teachers and public writers attentive to experiences in the field of popular education. However, in post World War I, the crisis affecting the Association, faced with the costly construction of its headquarters, beset by internal conflicts, tension and poor management, led to the intervention of the civil governor of Lisbon, who appointed a committee to reorganise the administration of A Voz do Operário.

The fourth period - 1926-1935: is the phase of reorganisation of the Association, marked upstream by the revision of the statutes, and downstream by the approval of the Pedagogical Curriculum and Regulation of the School Services. This period saw the emergence of a new generation in the managing bodies, where Raúl Esteves dos Santos and Domingos da Cruz gained prominence, in addition to the completion of the headquarters building and the move to the new premises, and the creation of proposals that reformed the various services of A Voz do Operário, particularly the school services.

The research on A Voz do Operário focused more extensively on the period from 1890 to 1935, interpreted in its fundamental articulation - associativism, education and welfare - by Ramiro Lopes (1995). With detailed research, focusing on the journal as a documental source, and supported by the scrutiny of other printed sources produced by and on the Association, this author stresses the importance of «Instruction» in the curriculum of the Institution, and shows how the debate on the pedagogical renovation/innovation of the schools of A Voz do Operário was occasionally resumed in the decades 1910-1920, without any position being taken, any plan drawn up and any model adopted. The literacy of the highest number of children and adults, with recourse to contracts with undifferentiated schools in order to meet the needs of the State in its support of the most needy and underprivileged, prevailed as a need over the criticism of «instruction, seen to be dogmatic, bookish and metaphysical», as opposed to «liberal, secular, positive and rationalist instruction». The idea of an «alternative model to that of the official education of the state was dispersed and emerged occasionally […], and was more the expression of a desire, the affirmation of an ideal than the proposition of a consistent and sustained project » (Lopes 1995, 129). This situation changed as of 1924, when the reform of the school services began to be regarded differently. The author analyses this process and ends the chapters on «Instruction» on this note (Lopes 1995, 100-173). As far as the reform of school services and the approval process of the Pedagogical Curriculum (1929-1935) are concerned, this paper complements the analysis of Ramiro Lopes, although it adopts a different approach, which has been made possible mainly by resorting to new documental sources from the archive of the Association7 and the personal archives of figures connected to A Voz do Operário8.

In the chapter given to the study of the school activities of the Association, the articles of Mesquita (1987) and Tavares & Pimenta (1987, 363-374) are worthy of mention, underpinned by the analysis of information and data collected in the journal, A Voz do Operário. Both depart from the connections between education and the workers’ movement during the First Republic and question whether the education of the Voz do Operário was an alternative to the official education of the state. The first author concludes that «with its educational model, A Voz did not constitute an alternative to state education, however its compensatory role [given the number of schools and pupils] was worthy of mention» (Mesquita, 385). The second authors, who note the divergence of the schools of A Voz from alternative models that were well received by worker, syndical and libertarian elites, such as the Escola Oficina n.º 1 [Workshop-School] and the rational schools of Francisco Ferrer, conclude that due to the «alignment with the state curriculum», a social promotion strategy of the members was at play (Tavares & Pimenta 1987, 374).

There are not many more works on A Voz do Operário. Despite the fact that it is an omnipresent institution, invariably referenced in articles on associativism, popular education and literacy9, architecture and urbanism10, and also in initiatives organised to oppose the regime of the Estado Novo11, and despite the news features in a number of thematic dictionaries12, there is no in-depth knowledge on this institution. The most significant lack of studies is related to the period of the Estado Novo. For recent years, the work of Pascoal Paulus on the School of Ajuda should be noted, since it sheds light upon the post 25 April period by studying the presence of the Modern Movement in the schools of the Association (Paulus, 2013).

Finally, a reference to some editions of the initiative of A Voz do Operário regarding its history, produced in a commemorative context (Santos 1983; Galhordas and Damas 1993). On the basis of this historical and institutional spirit, the Association also instigated the promotion of a monograph on the history of the institution, published in 2018, and written by Alfredo Franco. This work covers the entire history of the institution, from the foundation of the Journal up to the present day, including its expansion projects for the future. It systematizes the information available in the afore-mentioned works, contextualises, from a political and social perspective, the different phases that characterised the history of the Association, and provides detail in notes, through transcripts of the journal A Voz do Operário and various observations of the events, initiatives and figures that marked the life of the Association.

The institution (1890 - 1950s)

The Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário emerged enmeshed in a number of associative initiatives led by the workers of the tobacco industry, geared towards defending the class in the 1880s, This fight had begun with the publication of a journal in 1879. However, its designation is the result of the statutes approved in 1890, to grant the association, already open to the participation of other professional classes, the educational and welfare dimension its leaders and members had sought to develop (Lopes 1995, 28-43). In the formulation of its statutes, the goals of the institution were laid down in a clear and synthetic manner: to keep the journal A Voz do Operário; to create day and evening classes and a reading room; to support the members and their families with the provision of funerals. Thus, a functioning model was inaugurated which, despite its transformations across the various curriculum and practices processes, stood firm in its guiding principles throughout the 20th century.

In order to provide a brief presentation that covers its evolution, the 1920s to 1930s have been taken as a reference to highlight a “before” and “after”. In fact, these decades represent a turning-point in the history of the Association since they correspond to a renovating impulse, woven over the former experience of the association (as of the late 19th century), which activated the initiatives that marked its scope and later action which, in this analysis, extends up to the early 1950s13.

A Voz do Operário was a large institution that was founded, run and supported by workers belonging to different professional classes. All the activities developed within the Association were for these workers, the members and their families. The Association served as a reference among the associative body in the city of Lisbon, and its headquarters were located in the populated and popular Graça-São Vicente neighbourhood. It brought together a vast community, made up of thousands of members14.

As of the end of the 19th century, the Association offered a primary school network to its associates, with schools across the city, including evening classes for adults. The network was organised by the Association, consisting of four private schools, with premises and teaching staff who were recruited and paid by the Association itself. One of the schools was located in the headquarters of the association - the first to be inaugurated, in 1891. The other schools were housed in rented buildings, and established in the following years (1892-1895). In addition to this stable nucleus, there were also a number of private school establishments with which the Association had contracts. On the basis of a monthly payment, these schools would receive pupils who were the children of its members under the same conditions. This option was taken in 1895 in order to accommodate the explosion of demand. By 1905, there were already one hundred schools, and at the beginning of the First Republic, this figure had dropped to 84 (Tavares & Pimenta 1987). Contracts were entered into and terminated, according to the evaluation carried out by the Association’s School Commission on the quality of the facilities and the teaching provided by these private establishments. The pertinence of the location was also taken into consideration, and neighbourhoods with a large concentration of workers were sought. Despite these variations, the number of contract-based day schools tended not to surpass four dozen between the 1930s and 1950s15. The evening classes, limited to the school of the headquarters (private no.1), saw increased demand and, thus, were extended during this period to other private schools, as the Association understood that «giving value to its workers« was its «main mission»16.

The educational diversification, which was extensive to children (child’s class) and females (needlework and dressmaker course), and included other levels of education, such as professional (commercial course), began to take shape at the end of the 1920s17.

From this period on, other practices were also gradually incorporated into the educational programmes with the aim of qualifying education, such as medical-pedagogical observation and supervision (school doctor),18 holiday camps (the first was held in the summer of 1938), school excursions and field trips,19 the teaching of physical education and the constitution of fixed and mobile children’s libraries (as of 1938). This experience was highly successful and was entirely funded by a benefactor member, Fernando Rau. In 1939, the Children’s Library had four reading rooms, one in each private school and nine circulating libraries for the contract-based schools. Its collection consisted of 2 000 volumes, chosen for children and displayed on shelves for such purpose. The educational dynamization of this initiative also included lessons, projections, the reading of stories and the manual work section, accompanied by teachers20.

The educational dimension of the Association expanded further to include practices targeting adults, within the scope of intellectual, artistic, social and civic education and training, organised according to a programme with pedagogical and didactic concerns: these included lectures, conference programmes, theatre shows, concerts and cinema, although the recreational factor was not excluded (use of the Assembly Hall and open terrace, for less committed programmes)21. In 1943, the Museum of Work was founded, and also had an educational function. Organised around photographs and graphs showing the «Calvary of Man and the progressive evolution of industries» (Santos 1948, 9), it was backed by conferences on work-related themes.22

Finally, the Social Library, with a reading room in the headquarters and open to the public. As of 1943, it offered a book loan service.23 The library was the result of increased development, albeit arrhythmic, of one of the first initiatives of the tobacco workers in favour of the education of workers, embodied in the reading room (Franco 2018, 43). Its collections derived from regular purchases and donations, in addition to collections or libraries that were granted to the Association at different points in time by various entities that were complicit with world of workers, associativism and popular education, such as Boto Machado - a republican MP who fought in parliament for the social rights of workers, the Association of Pedagogical Studies (1910-1035) - a scientific association with particular activity in the reflection and dissemination of new pedagogical trends, and committed to the reform of education and national education (Pintassilgo 2007, 2) - and the Universidade Popular Portuguesa [Portuguese University of the People] (1919-1950) - one of the most important and long-lasting experiences within this social education model, designed for “the people” and promoted by the republican progressive and worker elites (Bandeira 1994)24.

In the field of its members’ welfare, the Association broadened its support network: in the case of death, it widened the funeral services implemented in the late 19th century25. It distributed trousseaux for the newborns of underprivileged families (1928) and provided general and specialized health care through the organization of a policlinic (1926). This welfare support also covered school activity through the provision of meals (school canteen)26, distribution of clothing, footwear and school material to the most needy children. It promoted the caixas escolares [school box with funds] and even awarded grants to the pupils who wished to continue their education at secondary school or through technical education. Financial support, in the form of school awards granted on a yearly basis, was also a practised method27.

As an institution, it sustained itself with its own funds - contributions and its own revenue -, but its «instructive» and «charitable» action allowed it to attract other resources, whether by means of public support, in the form of occasional subsidies, the granting of concessions or exemptions, in the form of donations from companies or individuals, and it also benefited from other forms of collaboration on the part of intellectuals, teachers, doctors, public writers, traders and businessmen (creation of awards for pupils, free provision of services, which could include the design of a building project, construction of a pavilion, the staging of conferences or a concert, the donation of books, foodstuff, and other assets or equipment, sometimes in the form of will inheritances)28. It also had a monthly journal which was distributed free of charge to members in its own typography, which kept the community informed about matters related to the Association, especially its management and administration.

An association designed within these moulds called for a structured organization of services, guaranteed by the managing bodies, elected every year in the General Assembly, supported by specialized committees (the sub-committees of a permanent nature or temporary committees), and by a paid workforce, admitted through documental tender. It also called for the fostering of a network of relations with both political authorities and legal and natural persons, and also the management of sensitivities and alignments, both within the Association and among the members. Many established relations with the Association by means of charitable action, but under distinct creeds. It should also be understood that they too expected to contribute to different results. Departing from this possibility, it may be considered that there were several goals in this social participation: as a type of social regulation, with a view to integrating the masses in the social order; as an inter-class conciliation strategy, with reformist objectives; or as a class strategy, seeking a shift away from the established political system (LÉON, 1983). «Une façon de faire la politique autrement» [A way of doing politics differently] (Christen & Besse 2017, 11-32).

Between the end of the 19th century and the early 1930s, the republicans, freemasons, libertarians, syndicalists and socialists were part of this force, organised into associations of different natures. Among them, there were competition and convergence strategies, depending on the political context. With the Military Dictatorship (1926-1933), followed by institutional standardisation, resulting from the approval of the constitution of the Estado Novo (1933), the action of these political groups was, naturally, constrained. The associative movement saw new rules, and many of them closed down. A new organisation was established by the Estado Novo. The political and social context changed. Precisely between 1924 - in a context of decline of the First Republic and of social and political confrontations, which undermined the associative movement and the worker organizations, and 1932 - the year when the political orientations were defined and the legal framework established under the Military Dictatorship, which would go on to result in the constitution of an authoritarian and cooperative political system - the Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário tried to launch an educational project, which went beyond what had been its usual practice- schooling, with limited social support, and social education through the fostering of reading (journal and library) and conferences - to focus on a far broader educational curriculum for the working class in which, another socio-political strategy came to light and is worthy of further research.

Reform of the school services - 1924/25 - 1935

The great venture of the Association, from the early 20th century, was the construction of its headquarters. The ambition of the project, accomplished in a monumental, large-scale building, suffered the consequences of the post-war social and economic crisis, causing the works to be delayed, costs to be increased and unrest among its associates. The construction of the headquarters, «considered by the most prudent to be madness» (Santos 1944, 4), was seen by the most critical as the result of a rash decision, which had led to «the sacrifice of the instruction services and other goals of the Association»29. Only at the end of 1923 did the services of the Association move to the new premises, but the building was not yet finished and only part of it could be occupied, and in adverse conditions. The classrooms had 80 pupils, and the fence around the playground needed to be bulldozed, and thus could not be used by the children, the terraces, on the upper surfaces, did not yet have protective railings, placing the pupils at risk, among other problems that affected the security and operability of the building30. Additionally, the managing bodies were confronted with salary complaints on the part of the Association’s employees, and a commission of auxiliary members had to be nominated in order to analyse the problem, and the administrative committees had not presented annual reports to the General Assembly for approval since 191931. Within this context, the civil governor of Lisbon suspended the elected managing bodies and appointed an Administrative and Inquiry Committee, which had the two-fold duty of reorganising the administration of the Association, and of investigating the institution, counting also on the intervention of the police authorities.

The Administrative and Inquiry Committee, 1924-1925

The committee consisted of a president, the representative of the civil governor, and seven board members, who were given their own areas of responsibility: instruction matters were attributed to Domingos da Cruz and general administration to José Maria Gonçalves32. The committee became effective on July 15 1924 and concluded its work on January 3 192533.

As Domingos da Cruz recalled later, “ we had to dig deep into the life and activities of the Association, especially the educational activities »34. However, at the root of the work he developed, in agreement with J. M. Gonçalves, as all proposals were approved by the Committee, was a new pedagogical orientation, seeking to define the « educational and instructive aims [for) the community» and to combat the «uncontrolled automatism» instituted in the schools and throughout the school services.35 In a few months, Domingos da Cruz drew up a plan with the architect to finish the works, proposed changes to the occupation of the space in order to rationalise the services, and managed to obtain a bank loan, authorised by the civil governor, to proceed with the works. In the pedagogical chapter, he invested primarily in pupil registration and observation methods, from the establishment of school statistics (attendance and performance, control of distributed materials) to school medical inspection (which included anthropometry, clinical testing, screening for diseases and abnormalities, special needs and socio-family evaluation) with the objective of better adapting the child to education. The filling in of these files, which were part of the pupil’s individual booklet, was conducted on the basis of the doctor’s coordinated observation with the contribution of teachers and family.

Domingos da Cruz also took many other measures so that the Association’s schools could once again function, from recruiting teachers, dividing classes, disciplining teacher practices, namely in the contract-based schools, to controlling observance of the pedagogical orientation, through regular inspections, for which he appointed a teacher. Finally, he invested in new educational methods which were added to the curricular programmes and were given equal importance: organisation of school excursions; establishment of caixas escolares [school fund boxes] managed by the pupils; constitution of a school museum; adoption of children’s songs and games in school practice, with a selection already made and approved to be distributed amongst the teachers. In the instructions to teachers issued by Domingos da Cruz, all these activities were justified since as a whole, they promoted physical, intellectual, moral, social and civic education, in addition to strengthening character and a sense of duty and solidarity. He also created mechanisms so that this curriculum could be effectively extended to all the private and contract-based schools of the Association36.

Normalisation after the inquiry: adjustments to the balance of power and new administrative structure

Two major issues raised by the Administrative and Inquiry Committee into the Society's management, for which a solution was necessary, continued to feature in the debates that engaged the members' attention at the general assemblies in 1925 and 1926: moves to challenge the supremacy of tobacco workers in the running of the Society, as established in the articles of association, limiting the participation of other groups or professional classes, and the neglect of educational and charitable work, seen as an abandonment of the founding aims of the association. These issues were debated in a climate of sharp internal divisions in the association.

It is important to note the levels of participation and representation of members. Only a relatively limited group attended meetings, comprising those members who were most militant in espousing the associationist cause. There were rarely more than fifty members present, including full and auxiliary members (who could speak, but without the right to vote), and attendance only climbed to around one hundred for elections. But measured against other organisations at the time, this was a substantial number. At one of the general assemblies, attended by only 30 members, the chronic nature of this problem was the object of comment: "things are what they always have been: a debate about goat's wool will fill a hall, but when questions of principle are at stake, no one turns up"37. And those most critical of this lack of participation argued that the number of members attending was not actually enough for the meeting to proceed, because otherwise "it looked like a stitch-up"38.

The ideological clashes, political mistrust and power struggles that emerge from reading the general assembly minutes are never openly discussed, but although they are always under the surface and emerge only in asides, they are nevertheless significant. For example, at one session it is stated that the "the delegation of officers from the Voz do Operário who went to speak to António Maria da Silva (1872-1950)39 told him that the Confederação Geral do Trabalho [General Confederation of Labour, an anarchist inspired grouping] wanted to take control of the Voz to spread its pernicious propaganda within the organisation"40. At another session, the tobacco workers present are accused of wanting to turn the Society into a "socialist stronghold"41. The caution in supporting O Socorro Vermelho (Red Aid)42, without first finding out about the organisation's aim led to a critical remark from a member about the "fear" that permeated the Society in relation to anything "red"43. And prior to this, the organisation has reacted with great firmness to reports published in a Catholic newspaper that the Voz do Operário's schools were recruiting children for the Legião Vermelha (Red Legion)44. The Tobacco Workers' Association had voiced vehement protests and the Society's directors decided to send a printed denial to all the "liberal associations in the country", in order to counter the effects of press criticism. The Society also gave its backing to an article in A Batalha - the journal of the Confederação Geral do Trabalho - denouncing the reports as untrue45.

These are just a few examples of many such instances, and point to a fundamental issue: the tobacco workers, who held socialist beliefs, aimed to maintain political control of the Society, and so they sought to limit the possibilities for involvement by anarchist groups, who had the upper hand in workers' movements, and to avoid contamination by Bolshevist ideas (the Portuguese Communist Party had been founded in 1921). In some ways, this re-enacted the struggle between socialists and anarchists in the trade union movement, when the influence of the former came under attack, in 1909, and the socialists were then driven out by the anarchists in 1917/1919 (Freire 1992, 193-197; Pereira 2009, 421-440). In this difficult balancing act, the tobacco workers' representatives preferred a strategy of closer relations with Republicans, and also with Republican governments. And we may infer that, in the management of the social question, this moderating force was favourable to the policy of Republican governments, whether of more conservative or progressive leanings. But the changes that opened up the membership of the Society to other classes and groups, allowing auxiliary members (all those not belonging to the tobacco industry) to register as full members (who had sole rights to vote and be elected, when male and of age), not only allayed internal tensions and ensured the organisation's sustainability, because of the need to refresh its leadership and officers, but also allowed reformist and Republican-leaning groups to take a more active part in the Society. These were able to integrate the working masses, open to more radical political ideas, in Republican political and social endeavours. This is a possible reading if we look at how the question of auxiliary members' status was eventually resolved.

The demands of auxiliary members pre-dated the work of the Administrative and Inquiry Committee. In its report submitted to the civil governor of Lisbon, the Committee proposed ending the "strange privilege" enjoyed by tobacco workers, "allowing many thousands of auxiliary members to vote and be eligible for elections, as compared to just a few hundred" workers employed in the tobacco industry46. In practice, this change was imposed on the tobacco workers and the Minister for Labour was obliged to intervene to secure a compromise. The minister called the president of the general assembly to his office because "he found himself being harried by both sides" and wanted to know whether the tobacco workers remained intransigent. He reasserted the need to admit as many voting members as possible and appealed for a consensus: "you sort it out, they [the auxiliary members] settle, what more do you want?" The response from the leaders was clear: they wanted to resolve the matter, but one question worried them - "the working class is divided into groups who could tomorrow turn on each other within the Society"47. The lists of auxiliary members for promotion to full membership were drawn up on the basis of political calculation48; the number of members was small, and both the auxiliary members and the minister were dissatisfied. It was then proposed that full membership be acquired on the basis of length of membership. And it was the minister who brokered the final solution: auxiliary members would acquire full membership after being members for fifteen years49.

This change was important for renewal of the association's leadership. It opened the door to influences more radical than the tobacco workers' orderly socialism and also to initiatives by Republican leaders, with a reforming and inter-class vision.

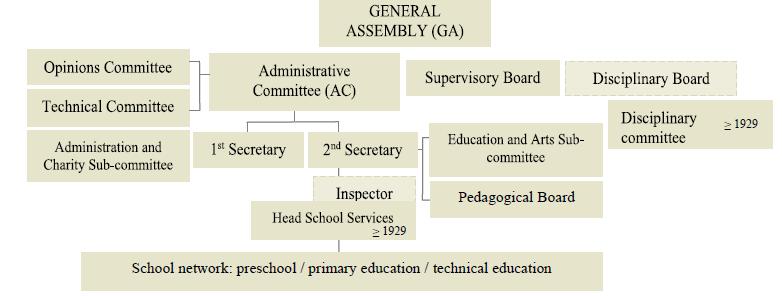

The new membership rights meant that the articles of association and internal regulations needed to be redrafted. But other changes were made, in particular to the administrative structure, and rules were established on new initiatives, mostly relating to the educational programme. We will deal very briefly with the changes made to the administration of the Educational and Arts Services (see diagram)50.

Diagram based on the regulations of June 1926 and May 1929

ADMINISTRATION OF EDUCATION AND ART SERVICES IN THE ASSOCIATION ORGANIC

The composition of the society's management bodies (the officers of the general assembly, the administrative committee and the supervisory board), elected annually, was unchanged, but they were backed up by new specialist bodies. Responsibility for educational and arts services lay with the 2nd secretary of the administrative committee (abbreviated below to AC)51 who chaired the education and arts sub-committee. This sub-committee comprised eight members, recruited from among the full and auxiliary members and approved each year at the General Assembly (below, GA), on the basis of a proposal from the AC. This body was responsible for studying the general thrust of educational activities, making contact with the "illustrious" teachers, with a view to "slow and progressive reform of educational methods", including the creation of new schools, using more up-to-date teaching methods and geared mainly to vocational education, equipping students for life;52 it was also required to study,

propose or organise a range of complementary educational activities (celebrations, talks, school visits to museums, factories and workshops, recreational excursions and school funds) and cultural activities (exhibitions, concerts, lectures, artistic and cultural events and festivals designed to educate the taste of members and their families).

Supervisory duties were assigned to a schools inspector, in permanent contact with all the Society's schools, whose task was to standardise the teaching methods, to monitor school activities on a regular basis, organising the administration of the entire network of private and contract schools, and also submitting a monthly report for the consideration of the 2nd secretary, to whom he was answerable for his work. The inspector attended meetings of the sub-committee. This post was filled through a competitive application procedure and applicants were required to hold a diploma from "normal schools" (training schools for primary school teachers)53.

The final element in this structure was a pedagogical board, with an advisory role, also chaired by the 2nd secretary and comprising teachers (three principals of private schools and four private and contract teachers) elected by the teaching staff at all of Voz do Operário's schools. The board met at the start of each school year, and also whenever called by the chairman or two thirds of the teachers. The pedagogical board was involved in planning timetables, choosing educational materials, planning celebrations and excursions and also issued recommendations when requested by the AC or the inspector and proposed changes and new initiatives in educational matters.54.

The new bodies and officers were therefore intended to bring new ideas and to oversee activities, improving administrative efficiency and contributing new expertise. The Education and Arts services were also supported by two boards that assisted the Society's administrative departments: the recommendations board, which functioned as the final arbiter of any proposal subject to the GA's assessment, and the technical board, which consisted of members with training in engineering, architecture and civil construction, including tradesmen in these fields, who advised the Society on works to be carried on in its facilities and school buildings, both those already existing and others which were planned55. In 1929, changes were made to the Society's General Regulations. The post of inspector changed its name to Head of Educational Services and, although the duties were unchanged, his work was recognised as that of "superintendent" of services, explicitly responsible for organisation and management of the educational division56.

It should also be noted that the sub-committees, appointed annually by the GA on the basis of a proposal from the AC, did not necessarily have to be set up if the board felt they were not necessary57. When the post was vacant, the head of Educational Services could also be appointed by the AC, dispensing with the competitive application procedure. The appointee could be one of the Society's teachers or someone from outside the Voz do Operário, provided he was "demonstrably knowledgeable of educational matters"58. These rules provided the AC with sufficient flexibility to mark out its position and relieve pressures, allowing for a more direct management approach in the event of an impasse, crisis or dispute59.

It was with this renewal of its organisational structure that the institution prepared to undertake the reform of its educational services.

Programmes and regulations − 1929, 1932, 1935

The first AC elected in the post-Inquiry period (the board of 1925/26) drew up a plan of action with measures to improve primary education, to develop educational support, introduce vocational courses, organise socio-cultural educational activities for members and to expand the welfare services for members (sanitary, maternity and childcare, and healthcare services) (Esteves 1933b, 9-10)60. The plan set down guidelines which were then followed by the management boards of 1926/27 to 1928/29 - set up under the new Articles of Association of 1926 -, but with new objectives and leading to visible results: the Pedagogical Programme was approved in 1929, followed by new regulations for the Educational Services. All this formed a structure for the ensuing attempts to transform the education offered at the Voz do Operário’s existing schools, and also to establish a new, much more wide-ranging educational programme. This was based on an educational model. Although the official programmes were complied with, the programme combined ideas from new pedagogical thinkers with the needs of its membership for whom it was intended. This involved aims that went beyond merely providing primary-level education and the promotion of an associationist "ideology" through the Society's journal or rituals centred on fostering an identity, as had previously been the rule61.

The Pedagogical Programme, organised in 16 sections (Sociedade… 1935), laid down that the care to be provided to the Voz do Operário's children had a threefold objective: "instructional, educational and social" (Section 1). This started with general education (sections 2 to 6), comprising primary education, which was decidedly practical in its approach (handicrafts and modelling) and based on observation, medical records and supervision. Furthering the students' health was an essential element of the process, and regular and methodical observation was an essential part of this. Students were assessed by the school physician and divided into groups for physical education lessons accordingly. Free meals were provided for the neediest children, complemented by the provision of restorative medicines and advice for families on care (including clothing and diet). This concern with health was extended to the school facilities, with standards for buildings and furniture, designed to be educationally appropriate. School excursions were also planned to be beneficial for students' health, and along with drama, singing and choirs were intended to contribute to forming character and cultivation of the arts.

General schooling was followed by special training (sections 7 to 14), in order to assure an all-round education. Plans were to be drawn up for vocational schools, with theoretical and practical courses, covering elementary business studies and a range of trades. Also envisaged for the future was a people's technical university, offering further and higher education courses (in industry and commerce), and plans for future building work included a boarding school and a school with partial boarding facilities. The principles of the associationist and cooperative movement were built into all parts of the syllabus. This took practical form in school associations, administered by the students, and cooperatives for production and consumption, organised around the workshops set up for practical training in the vocational courses.

With this educational model, the Society planned to "prepare students for life" and to care for their welfare, which started with their health and ended with their being helped into the employment market. But the support for student would not end there. There was follow-up for their future development, both in society and in their private life. Because this was the only way to assess the social role of the Association "as the great conglomerate that it is and in its lofty mission of building Portuguese society" (Section 10).

One of the leading figures in the administration of the Society, who saw through the drafting of the Pedagogical Programme and secured its approval, was José Gregório de Almeida (1883-1954), chairman of the AC, re-elected on successive occasions. He was a bookkeeper, active trade unionist and socialist Member of Parliament62. Shortly before first taking up management office in the Society, in the wake of internal disputes, he proclaimed at a general assembly: "We are performing a lofty social mission, our achievements cause fear among the bourgeoisie"63.

Individuals who served for two or more years on the Education and Arts sub-committee, appointed by these management bodies64, included in particular: João Camoesas (1887-1951), doctor and politician, Member of Parliament for the Republican Party (1915-1926), Minister for Public Education (1923 and 1925); Manuel da Silva, primary teacher at the Casa Pia, union activist and anarchist sympathiser, member of the most important teachers' associations, such as the União dos Professores Primários and the Associação dos Professores de Portugal; Amílcar Costa, shop worker and republican; Alexandre Vieira (1888-1973), typesetter, revolutionary union activist and one of the most prominent union leaders under the First Republic; Maria O'Neill (1873-1932), author of children's books, involved in movements to advance children, women and education. And in 1928, these were joined by Domingos da Cruz (1880-1963), first lieutenant in the Navy, republican, Member of Parliament for the Republican Party (1915-1921), and Augusto Carlos Rodrigues, bookkeeper, anarchist.

This is a politically and socially very active group, both in Parliament and in trade unions. And they were all involved in the people's education movement, belonging to several institutions, where they sat on the committees or lectured. They also wrote in the associative press, generally on educational matters. All of them shared an active interest in education, were familiar with the latest experiments conducted in Portugal and abroad and, despite belonging to different political movements, were all committed to improving the lives of the working classes.

Domingos da Cruz, for example, was a member of various associations, such as Escola Oficina no. 1, the Asilo de São João and Centro Boto Machado, all linked to the freemasons, to which he belonged. He was also involved in the Universidade Popular Portuguesa, in which Alexandre Vieira and Augusto Carlos Rodrigues took a very active part, forming a bridge between the working class movement and anarchist tendencies with critical and reform-minded Republicans, represented by the Seara Nova Group (Bandeira 1994). As well as his career in the Navy, where he started as a nurse, D. Cruz also had a political career, as Member of Parliament and chief of staff to the Ministers for Labour and the Colonies (1919-1923). He was also appointed to public service boards on employment matters. In the Chamber of Deputies, in 1917, in a debate on draft tenancy legislation, he called for strict enforcement of the law that seeks to protect poorer classes against speculative landlords: "The people want building projects, they want the Republic to live up to what they very legitimately expect of it." And if this course is not taken, he warns that "debts will be contracted, that sooner or later will have to be paid"65. But however just, he also considered that some of the demands of the working class movement were excessive, and if they were maintained would eventually "spell the end of the Republic and perhaps result in a major reverse in Democracy"66. He was a reformist: he had regular contacts with union and anarchist leaders, and close relations with Alexandre Vieira, Emílio Costa, Campos Lima and Pinto Quartin, the last three of whom were intellectuals and the leading anarchist thinkers in Portugal67. Domingos da Cruz had taken part in the Administrative and Inquiry Committee into Voz do Operário, in 1924. He returned, four years later, to complete the process of pedagogical renewal that he had begun, The Pedagogical Programme is all his work. And to apply it, Adolfo Lima (1874-1943) was appointed, on his suggestion as head of Educational Services. Lima also drafted the regulations for the services.

Lima was one those responsible for disseminating the New Education movement in Portugal, among associations, and in the fields of education and publishing. He was a teacher and principal of Escola Normal de Lisboa and Escola Oficina no. 1, he established the Portuguese section of the International League for New Education (1927), founded and edited the journal Educação Social and, from 1911 to 1930, sat on a series of committees appointed to draft legislation on primary education. He was one of the leading thinkers in the Portuguese anarchist movement and worked with trade unions on drafting theses, in particular on education. He sat on the management bodies of the Sociedade de Estudos Pedagógicos (Educational Studies Society) and the Universidade Popular Portuguesa (Portuguese People's University)68.

The experiment at Voz do Operário proved a failure and Lima eventually resigned, in July 1930. At that date, the services were "in a state of disarray" and the teaching staff floundering "Because they had not understood the new form of education"69. Critical voices within the AC considered that one of Lima's mistakes was to alter the educational system half way through the year and in classes that had started by using other methods. There were disagreements with teachers, who defied instructions and continued to teach as before, with parents, who could not understand why their children spent so much time in the playground, had no books to learn from, no tuition and no homework. Parents and teachers alike feared that students would fail to pass the final examination. Among other problems, the AC decided not to appoint another principal and instead to look into the possibility of implementing the pedagogical programme. The secretary responsible for education surrounded himself with people qualified to do this. During this period of appraisal and reflection, the schools returned to the old teaching methods and the innovative teaching activities set up by Lima (crafts, modelling and drawing) were then incorporated into the syllabus for primary level classes70.

In the summer of 1929, shortly after being appointed as head of educational services, Adolfo Lima referred to the work he was involved in at the Society, expressing a degree of incredulity at the situation he encountered there: private school no. 1 (at the headquarters) alone had 612 students and 13 teachers, and there were more than 28 schools around the city, with close to 3000 children. He also pointed to the disorganised state of the administrative and pedagogical services (Candeias, Nóvoa and Figueira 1995, 127). This was very different from the situation at Escola Oficina no. 1, where Adolfo Lima became famous for organising a successful alternative model of education, long before this new experiment (1906-1915). When student numbers were greatest, enrolments at the start of the school year numbered around eighty (Mogarro e Andrade 2019, 191-192). Despite the difficulties, A. Lima confessed that he had already set up a modelling and drawing class and a craft workshop and expected that year to set up a physics room and a chemistry laboratory. He also stressed that the Society also offered evening classes for women and that he was extremely committed to their development and advancement. More than a year on, after tendering his resignation, Adolfo Lima confessed that, on accepting the appointment, he had suspected it would be impossible to achieve anything, but that he accepted the post for the benefit of the doubt. But it had been a mistake, he reckoned, because his work had not been useful and had been lost among the Society's routines, that blocked out any innovation:

"Behind the Voz do Operário lies the huge unmovable rock of the routine business of the symbolic 'funeral cart'.

They are concerned about the number of students and not the quality of the teaching and education. Their aim is for students to pass exams, and not for them to acquire knowledge and healthy minds. And however hard you row against the current, it's not possible to do anything useful. I was overwhelmed, and Domingos da Cruz was also overwhelmed […].

What is more: if bourgeois employees are difficult to bear and drive us mad with their stupidity, working class employers are even harder to bear. When our 'good comrade' sets himself up as boss, he's a hundred times more authoritarian and rude than the most bourgeois of the bourgeois!"71

The suspended regulations dealt only with primary education and applied to the existing schools. As established in the Pedagogical Programme, vocational education remained under consideration for the future, depending on the Society's resources (Section 16, par. 2.).

The management board of 1931/32 then drew up new draft regulations, submitted to the AC by the sub-committee, in 193272. This was an ambitious draft text, organised in 20 titles and 662 articles, adhering to the ideas of the Pedagogical Programme. But it elaborated on these, clarified the aims and provided curricular and methodological details, creating a body of rules too vast to be examined in full here. We shall instead consider the main thrust of the document.

The starting point for these Regulations was an aspiration to educate young generations within the "Society's ideology" and following an overall plan that established the purpose of the varied activities. It accordingly required programmes, teacher recruitment and the education provide to students to "comply with the ideological principles of the Association"73. To this end, it was necessary to remove children and young people from the influence of their families and to keep them under the Society's influence for the duration of their education. In order to achieve this, they proposed an education system organised by grades and age ranges, in line with an all-round educational approach, achieved using active methods and processes, built into the programme, combined with work to protect children and with sufficient years of schooling to prepare students for life.

This education started in nursery classes, intended to cater for children between one month and three years of age, during their mothers' working hours. This was followed by infant education, from the age of four, designed to allow children to acquire physical strength (care with diet and hygiene, physical exercise in the open air), and to learn habits and skills and to be subject to intellectual and social stimuli, graded in accordance with their age. With the aim of "providing children with the fundaments of all knowledge and the basis of a general culture, preparing them for life in society"74, primary education started at the age of seven, on a co-education basis, followed by complementary education, also organised on a co-educational basis, for children aged twelve to fourteen. This level of education was designed to help youngsters discover their skills and vocations, and was compulsory for all those then seeking to follow vocational courses. The final stage was education for a trade, divided into several courses lasting three or four years, attended between the ages of 14 and 16/18, in daytime hours, with girls and boys taught separately75.

The regulations also provided for special education, to be offered at primary levels, with classes for the handicapped and retarded children, as well as university extension courses for adults, in social and cultural education.

The document was unanimously approved by the AC. Before being submitted for debate at the GA, the chairman of the AC decided to present it at a general assembly of management staff, to which he invited managers from other institutions76. It was then forwarded to the recommendations board which, after listening the opinions of experts, decided to put the text to the members, leaving several copies in the library. Seven months later, the regulations were still at the committee stage77. They then disappeared from view.

It should be explained that the 1932 Regulations were drawn up by Mariano Roque Laia (1903-1996)78, a lawyer, Republican and freemason, also a teacher at the Casa Pia, who as a young man had started to work with the Voz do Operário, as a teacher for evening primary classes, in the 1920s, rising to principal, until he left the institution in 1928. He was chosen to fill the vacancy left by Adolfo Lima. Work needed to continue on applying the Pedagogical Programme, and according to the chairman of the AC in 1931/32, Roque Laia fitted the requirements:

"Knowledge of new theories and ideas about teaching, capable of putting them into practice without undermining the smooth running of education. Someone who would neither get lost in theoretical ideas in his office, nor have an exclusively hands-on empirical approach, nor so ideologically backwards as to jeopardise the associations work, nor so strongly political as to put political ideals ahead of other considerations in his work." (Esteves 1933b, 54-55)

Roque Laia held the post of head of educational services from September 1931 to July 1933, when he resigned because of an open dispute with the administrators. He took a forceful approach to his work and, according to Esteves dos Santos, succeeded in securing resources and organising activities that brought about the desired renewal in the Voz do Operário's schools79. And the 1932 Regulations reflect this forceful character, although the association was unable to keep up with the pace they set. He had the backing of Esteves dos Santos (1889-1954), a central figure in the administration of the Society, since 1929, when he was appointed as chairman of the Supervisory Board, until the 1940s, alternating between the chairmanship of the GA, the AC and the supervisory board.

Raúl Esteves dos Santos was born in Lisbon to a working class family, left school at ten and then educated himself. The earliest references to him in public office are in the years following World War I, as belonging to the moderate Republicans, and he worked in the office of José Relvas (1919) and was secretary to the Minister of Finance, Peres Trancoso (1921), to the civil governor, Agatão Lança (1921-1922) and to the Minister for Trade, Ferreira da Fonseca (1923-1924). He was an employee of Lisbon Municipal Council (1925) and held several posts in the state railways company (1925-1929). He was a prolific writer and lecturer. In addition to writings on the history of the Voz do Operário, as we have seen, he was interested in reflecting on the causes that led to the end of the Republic political experiment and on issues relating to labour (copyright, rest periods for workers and vocational education). From 1931 onwards, he delivered more than a hundred lectures up and down the country. At the time of his death, he was working on a volume on the associationist movement in Portugal and the extent of its civic participation, having worked with a variety of working class associations80.

The changes to the AC, after the power struggles that led to Esteves dos Santos (1933) resigning from his post, once again stalled the process of reform. But the following year, Emílio Costa (1877-1952) was contracted as head of educational services. He was another leading figure in the Portuguese anarchist movement, both as theorist and populariser, as well as a man of action, in particular in the field of working class education, both in anarchist institutions and in collaboration with Republicans, such as the Universidade Popular Portuguesa, as well as in association with the trade union movement. He was a teacher at secondary and technical schools, fully familiar with new currents in pedagogy, and an educational thinker and writer since his time in Belgium (New University of Brussels) and France, between 1903 and 1908, having worked as secretary to Francisco Ferrer. From 1927 onwards he was on the staff of the Instituto de Orientação Profissional (Vocational Guidance Institute). It was in the same year that Domingos da Cruz rejoined the Education and Arts Sub-committee (administration of 1934/35). Continuing the reforms entailed reintroducing the regulations that had been suspended in 1930. In his own words, the latter modelled the system devised by Adolfo Lima81. This took effect in December 1935 and remained in force until at least the 1950s, but not without countless difficulties and lacunae.

In effect, in 1947, the AC alluded to the need to review the Regulations of 1935 and the following year mention is made of "continuing moves to reform the educational services"82. In 1949, Domingos da Cruz took on the chairmanship of the AC. In the late 1950s, he wrote about his return and his experience at the Voz do Operário since he sat on the Administrative and Inquiry Committee:

"I was pained by the neglect that had crept into everything. The attempts at renewal in 1924-1925, the weary efforts in 1929 through to mid-1930, resumed in 1934 to 1936, but in these last two periods without management responsibilities, although I was not able to excuse myself from sitting on the Educational Board, due insistent and repeated requests, almost everything was lost. I found the Society in debt, not deficits, it should be noted, of tens of thousands of escudos, everything filthy inside, unsuitable furniture in a deplorable state, junior staff in worn out uniforms, all teachers poorly paid, etc., etc., as can be seen from my management reports. No educational welfare services, biometrics, records, a gymnasium that pretended to offer physical education to the children, the very devil."83

Notes by way of conclusion

In the mid-1920s, the idea of educational reform was forced onto the agenda by a crisis in the Society and driven by the effects of intervention from outside the normal functioning of the institution, as the result of regulatory interference by the State in associations, especially when they were awarded public utility status and enjoyed State benefits. These regulatory interventions were administrative and financial in nature, but also entailed "remote" political control. As we have seen, the openness to multiple political influences made it possible to broaden the political spectrum and, alongside more damaging currents or those with more radical social aims, progressive republican ideas were also allowed in, with a reform-minded approach, seeking to integrate the working classes. With the renewal of the management boards of associations, it was hoped to renew policies and initiatives in the field of education and social welfare, viewed by the Republican State as complementing its government policies. Anarchist and trade union organisations, later joined by the communists, were already using political, social, vocation and associationist education to prepare the working classes for the future social revolution.

In effect, with the administrative reform (1926), the Society was able to renew its boards, within an associative management and decision-making model, and at the same time to equip itself with the means to implement a different educational and social policy. In order to plan and assess this, it had members from all walks of life, recruited from the workers', intellectual and artistic elites and drawn from a varied social, political and cultural spectrum; in order to implement it, it had a body of teaching and administrative staff; in order to direct and approve its policies, it had a relatively limited group of more active members, with working class roots, who sat on the different management bodies on a rotating and alternating basis; to approve everything, it had a general assembly of members, also relatively small in size and mostly made up of the more militant and active members, grouped by personal, professional and political affiliations; and lastly, it had a membership of several thousand, although shrinking, whose subscriptions provided its basic revenues and whose number needed to be expanded by attracting new members, as well as by living up to their social expectations84.

Despite the progress, setbacks and impasses, the educational model that was designed and partially put into practice was the work of a small group of members, with contrasting ideological influences, but who agreed on the importance they attributed to the associationist movement, as a form of civic organisation and participation, and to a new form of education, with organisational models, methods and practices to primary and vocational shape schooling and education, as well as adult education, using the people's university model.

This endeavour was aimed above all at the underprivileged working classes, and set out, upstream, to tackle the social ills of disease and poverty, and downstream to equip individuals with a trade, suited to their personal abilities and vocation. The connecting thread in the whole education process was the concept of a single school, for children aged 4 to 16, that sought to provide intellectual, social and cultural education, to create a spirit of enterprise and students initiated in the life of society, that the school reproduced, through the teaching of welfare practices and social solidarity. Lastly, it should be noted that the model designed was centred in particular on promoting the physical development of the student (diet, physical exercise, management of school time, play, holiday camps, health inspections, screening for diseases and disorders, matching school work to the pupil's abilities, skills assessment and vocational guidance), and placed the school doctor and medical-psycho-pedagogical at the heart of school life and education. Vocational courses represented the final link in this chain.

The model was not original. But it was innovative, because it was proposed by an association of workers and functioned in a closed circuit. It incorporated ideas from New Education which, in the late 1920s, were embraced by workers' movements and teachers' organisations sympathising with revolutionary trade unionism and anarchism, such as the Associação de Professores de Portugal, the Liga de Ação Educativa and the União dos Professores Primários. The associationist ideas also influenced republican initiatives, and even those of governments and municipalities. Examples of these included: the project for Public Educational Reform, presented by the minister João Camoesas in 1923, which was never debated in Parliament, but which rekindled the debate on the école unique and was warmly welcomed by those associations and by Adolfo Lima and Emílio Costa (Nóvoa 1986, 114-115); the project led by Alexandre Ferreira, as municipal councillor, for setting up a model primary school85; and the educational programme for public welfare educational establishments, on a boarding basis86. All these programmes were devised by Faria de Vasconcelos, the Portuguese pedagogue, whose ideas were formed within the New Education Movement, a close associate of Ferrière, and the founder and director of the Instituto de Orientação Profissional (Vocational Guidance Institute) (1926)87. All of these, in some cases explicitly in the supporting texts, exerted an influence on the programmes and regulations of the Voz do Operário. With the exception of Faria de Vasconcelos, the members of the sub-committees included, as we have seen, Camoesas, and also Alexandre Ferreira, a Republican, founder of a people's university and municipal councillor in the 1920s, in which post he is remembered for his achievements in education and welfare. This influence extended also to teachers, figures drawn from the social networks of professionals and academics, formed around the Instituto de Orientação Profissional, or the Casa Pia de Lisboa, a charitable institution for minors.

But more detailed research will be needed on how expertise in educational innovation circulated in Portugal, and in particular on how these ideas shaped the reform of the educational services of the Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário.

REFERENCES

Arquivo Histórico-Social/Projeto MOSCA - Espólio Adelino Augusto Ferreira http://mosca-servidor.xdi.uevora.pt/projecto/index.php?option=com_jumi&fileid=7&p=collections [ Links ]

Arquivo de História Social-ICS - Espólio Pinto Quartin [ Links ]

ANTT, Fundo da Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário. Available in https://digitarq.arquivos.pt/details?id=4641905, last access 2018.04.30. [ Links ]

Assembleia Geral, Atas da, 1917-1925, 1925-1928, 1932-1934, 1934-1935. [ Links ]

Biblioteca Infantil, 1937/1939. [ Links ]

Comissão de Pareceres, Atas da, 1926-1955. [ Links ]

Corpos Gerentes, Atas dos, 1928-1956. [ Links ]

Comissão Administrativa, Atas da, 1924-1925, 1925-1928, 1928-1930, 1930-1934, 1934-1937. [ Links ]

Domingos Cruz, espólio de [correspondência, décadas 1920-1950]. [ Links ]

Livro de Autos e Ocorrências, 1931-1934. [ Links ]

Relatório apresentado pela Subcomissão de Instrução e Beneficência em Março de 1932. [ Links ]

Relatório do Chefe dos Serviços Escolares, Augusto Alberto Sanches, 18.08.1938. [ Links ]

Relatório e contas e parecer do Conselho Fiscal. Gerência de … 1934/35 a 1965. [ Links ]

FMS (Fundação Mário Soares. Casa Comum) - Fundo de Alberto Pedroso. Available in: http://casacomum.org/cc/arquivos [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Brocas, Manuel de Araújo. 1938. A Biblioteca de A Voz do Operário: 1888-1938. [S.l. : s.n.]. [ Links ]

Cruz, Domingos da. 1947. O Ensino em Portugal. Alguns números e comentários em prol do ensino profissional. Lisboa: s.n. [ Links ]

Diário da Câmara dos Senhores Deputados, 1911-1921. http://debates.parlamento.pt/, último acesso em 22.02.2019. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estatística. 1945. VIII Recenseamento Geral da População no Continente e Ilhas Adjacentes em 12 de Dezembro de 1940. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos. 1932 b. «A Voz do Operário, Grande Seara de Luz.» Almanaque Pensamento, 1:174-181. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos. 1933 a. A Grande Epopeia dos Humildes. Lisboa: SIBVO. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos. 1933 b. Três Anos na Grande Colmeia. Lisboa: edição do autor. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos. 1936. Figuras Gradas da Voz do Operário. Lisboa: SIBVO. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos 1938. «A história da Voz do Operário». Gazeta dos Caminhos de Ferro, 1204: 97-99. [ Links ]

Santos, Raúl Esteves dos 1947. O Ensino Técnico e Profissional sobre o Ponto de Vista Histórico. Lisboa: SIBVO. [ Links ]

Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário. 1926. Estatutos e Regulamento Interno. Lisboa: Tip. De A Voz do Operário. [ Links ]

Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário. 1931. Estatutos e Regulamento Interno. Lisboa: Tip. De A Voz do Operário. [ Links ]

Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficência A Voz do Operário. 1935. Programa Pedagógico, Bases Orgânicas das Associações Escolares e Regulamento dos Serviços Escolares. Lisboa: Tip. Privativa de A Voz do Operário. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Bandeira, Filomena. 1994. «A Universidade Popular Portuguesa nos Anos 20. Os intelectuais e a educação do povo: entre a salvação da república e a revolução social». Tese de Mestrado. Universidade Nova de Lisboa. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/14306. [ Links ]