Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.19 no.1 Uberlândia jan./abr 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v19n1-2020-15

Artigos

Memories in Palimpsesto: Buildings and school spaces in student narratives in Porto Alegre/RS (1920-1980)1

1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil) lucascgrimaldi@gmail.com

2Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil) almeida.doris@gmail.com

The present study investigates oral memories’ narratives of students about spaces and school buildings inhabited by them, from 1920 to 1980. Its main objective is to produce a kind of cartography of the sensations about the spaces lived during schooling, Identified in the documentation. The research privileged the examination of the discursive content of the eight interviews carried out using oral history methodology. From the analyzes of recurrences and dissonances in the narratives, two categories of analysis were constructed: "The Old and the New: relationships between students and school buildings"; "Between surveillance and fun: the school space as a curricular element"; For the research, the spaces of schooling acquire a prominent place at the time of remembrance. These memories, loaded with resignification, bring evidence to understand school architecture as an agent in building student sensitivities.

Keywords: School Architecture; Student memories; Sensitivity

O presente estudo investiga narrativas de memórias orais de estudantes acerca de espaços e prédios escolares por eles habitados, no período de 1920 a 1980. Tem-se como principal objetivo a produção de uma espécie de cartografia das sensações sobre os espaços vividos durante a escolarização, identificadas na documentação. A pesquisa privilegiou o exame do conteúdo discursivo das oito entrevistas realizadas, tendo como metodologia a História Oral. A partir das análises das recorrências e dissonâncias nas narrativas, construíram-se duas categorias de análise: “O Antigo e o Novo: relações entre os estudantes e os prédios das escolas”; “Entre a vigilância e a diversão: o espaço escolar como elemento curricular”; Para a pesquisa, os espaços da escolarização adquirem um lugar de destaque na hora de rememorar. E estas lembranças, carregadas de ressignificação, trazem evidências para compreender a arquitetura escolar como agente na construção de sensibilidades estudantis.

Palavras-chave: Arquitetura Escolar; Memórias discentes; Sensibilidade

El presente estudio investiga narrativas de memorias orales de estudiantes acerca de espacios y edificios escolares habitados por ellos, en el período de 1920 a 1980. Se tiene como objetivo principal la producción de una especie de cartografía de las sensaciones sobre los espacios vividos durante la escolarización, identificadas en la documentación. La investigación privilegió el examen del contenido discursivo de las ocho entrevistas realizadas, usando como metodología la Historia Oral. A partir de los análisis de las recurrencias y disonancias en las narrativas, se construyeron dos categorías de análisis: "El Antiguo y el Nuevo: relaciones entre los estudiantes y los edificios de las escuelas"; "Entre la vigilancia y la diversión: el espacio escolar como elemento curricular"; Para el estudio, los espacios de la escolarización adquieren un lugar destacado en el momento de rememorar. Y estos recuerdos, cargados de resignificación, traen evidencias para comprender la arquitectura escolar como agente en la construcción de sensibilidades estudiantiles.

Palabras clave: Arquitectura Escolar; Recuerdos discentes; Sensibilidad

Students and school architecture: memories of sensible experiences

When Carlos entered the school, he got surrounded by the gloom coming from its high walls, by that peace from the desert patios, by the strange man that walked on his side, by the monotonous and nostalgic music that filtered through the windows with colored glassware. (Martins, 1992, p. 38)

When we think about childhood memories, what do we easily remember? We can say that, for formally educated people, school memories may seem to want to escape from oblivion.

In the epigraph above, it is possible to observe the importance that the mentioned school building has for Carlos, the story character. In this case, the magnificence of the building produces senses that are internalized by him and thus are not forgotten; it consists in discourses that produce sensations in this student. This is not a prerogative of the character created by Cyro Martins. In an ample perspective, it is possible to perceive that school buildings and spaces are not only “physical support structures for education” (DÓREA, 2013, p. 162); they are not passive structures2.

This study investigates memories related to school buildings and spaces, discussing the sensible experiences evoked by students from four educational institutions located in Porto Alegre, between 1920 and 1980. We selected for analysis the buildings and spaces from the following school institutions: American School (Colégio Americano), established by the Methodists in 1885; Anchieta School (Colégio Anchieta), founded by the Jesuits in 1890; Farroupilha School (Colégio Farroupilha), created by a German immigrant group in 1886; and Rosário School (Colégio Rosário), founded by the Marist Brothers in 1904. The documentary corpus is consisted of former-students' oral narratives produced by means of the Oral History methodology.

The study's initial landmark is the 1920s, when American School and Rosário School built their first buildings at Independência Avenue, a place in which the bourgeoisie houses were located at the beginning of the 20th century. The final landmark is the decade 1980s, when Anchieta School finished its current architectural complex and inaugurated the school's Sports Gym. In addition, this delimitation was established due to the oral sources we collected: interviewee Nelly started to study at American School in the 1920s; and the last interviewee, Sergio, finished his studies at Rosário School in the 1980s.

Each narrative is a rich version of representations concerning sensible experiences. This research, therefore, provokes questionings: What changed in the buildings and in their architectural conceptions? What is the relation between students and these spaces? What memories can be evoked concerning the buildings and the schools' surroundings?

According to Farge (2009, p. 88), “each actor testifies what he saw and the singular way through which he bounded with the event, improvising his position and his gestures, with vehemence or hesitation as the case may be”. His words elucidate the intentionality and the central objective of this text, that is, the discussion concerning memories and individuals' sensibilities.

To share the meanings of an interview event, to practice the act of patient listening, and to get to know memories of others are actions loaded with symbolisms; thus, perhaps this is the reason why this study becomes rich in terms of possibilities and interpretations. Care was taken to produce narratives that emphasized the interviewees' sensibilities in the crossing with the history of these schools' architecture, in order to discuss their ways of using school spaces, which frequently were adapted to different activities. There was also a concern in reasoning about what was said by the narrators. In this regard, the research sought to know the representations constructed and the practices developed in those places, as well as to capture the relations between individuals and urban spaces in which they have spent part of their lives.

We produced a sort of articulation between urban cultural history, students' memories, and school architecture. After all, schools are not separated from their urban context, nor are their buildings distant from students. This articulation is important, because schools must be studied without being dislocated “from the social, cultural political, and economic context outside its environment” (BRESSAN, 2013, p. 34), thus it is necessary to avoid the risk of isolating these institutions when studying them. From this decision of not isolating the object of study, emerged the interest in studying History of Education and relating it with the explored city, especially considering an aspect that brings history and urban spaces together: school buildings. These places are "endowed with meanings and transmit an important amount of stimulations, contents and values” (ESCOLANO, 2001, p. 27). Therefore, they are a “cultural construct that expresses and reflects, beyond its materiality, certain discourses” (ESCOLANO, 2001, p. 26). This is a recent way of perspectivizing school architecture, considering that, along many years, there was a predominance of the analyses conducted by architects and art historians. In this regard, these buildings were analyzed, mainly, from their structural characteristics and ornamental elements.

We understand that it is necessary to consider the complexity of such school buildings and spaces. For this purpose, the concepts of palimpsest and pastiche are important; they are framed in regimes of historicity. The palimpsest was used by Pesavento (2007, p. 17) to demonstrate and to exemplify the writings and rewritings of the urban space, from the metaphor of the parchment, a tool that was used by medieval monks, and required to erase what was already written in order to write a new text; thus, each rewritten piece contained traces of the previous one. As well as cities, school spaces are also written and rewritten many times, either through their materiality or by the memories of their students.

As pastiche, we can observe different kinds of overlap in school spaces, including constructions of different temporalities, with distinct functions, which occupy these institutions that, at the same time, preserve and build new spaces, generally with the intention of mimicking old buildings. For example, in the 1970s, the Rosário Marist School created a building that mimicked a 1930s' construction, which was used as a Boarding School at the time. According to Milton Almeida (2010, p. 504), by means of pastiche, we are assuming diverse “stories of transitory and significant agglomerations of Chaos”.

Finally, considering the concept of regimen of historicity, we understand that school buildings, spaces and memories are products of certain historical conditions and of specific temporalities, which express a much more complex range of meanings than one can imagine.

From these considerations, we can think about school buildings as “the form of a historical condition, the way an individual or a group is constituted or developed over time” (HARTOG, 2014, p. 12), in addition to the way this group builds and destroys its constructed heritage. We are interested in analyzing these pastiches, palimpsests, vestiges that were reconceptualized in the memories of these interviewees, who, within school buildings and spaces, built their identity as students through subjectivation processes.

Along the research, we conducted eight interviews with two students from each institution. On Table 1, we list the name of the interviewees and bring some information about them.

Table 1: Brief presentation of the interviewee

| School | Name | Age | Schooling Period |

| Farroupilha School | Ana Luisa | 49 years old | 1972-1977 |

| Martin | 70 years old | 1952-1963 | |

| American School | Elaine | 73 years old | 1952-1963 |

| Nelly | 101 years old | 1921-1932 | |

| Anchieta School | Fernando | 80 years old | 1947-1952 |

| Marcos | 47 years old | 1973-1980 | |

| Rosário School | José Eduardo | 65 years old | 1966-1968 |

| Sergio | 54 years old | 1969-1977 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Five of the interviewees are men, and three are women. This distribution is related to the history of these schools: until the end of the 1970s, Anchieta and Rosário schools only accepted boys, while American School accepted only girls. On the other hand, Farroupilha School has accepted boys and girls since 1929.

The fear of going, for the first time, through the gates of a school, the anxiety in the first day of class, the claustrophobia that some places provoke, the fondest memories, and the most painful ones related to school places: all these aspects are addressed in this paper. Considered by Pesavento (2007, p. 10), as "an adventure of individuality”, sensibilities have a historicity that place them “on the edge of the history of ideas, representations, bodies or images” (GRUZINSKI, 2007, p. 7). They can be handled as representations of the past, which are found by historians through discourses, through multiple languages.

In this regard, Pesavento (2007, p. 21) states that to study this subject “is not to feel the same way, it is about trying to explain the way a sensible experience could have been in other times, according to the tracks it left”. It is not easy to perceive these signs; historians who work in this perspective must sharpen the look in order to apprehend what these narratives say, in their individualities.

By means of the analysis of discourses emerging from the collected oral memories and the school buildings, it was possible to study the way these spaces affected students, that is, the extent to which these spaces watched, molded, punished students, and instilled ideas. Beyond observing the way individuals felt these spaces, our goal was “to identify the use of senses that evoked the construction of images of others, to shape social imagery” (CORBIN, 2005, p. 19). From the aforementioned themes, two analytical categories were established: "Between old and new: spaces in transformation" and "Between monitoring and leisure: space as a curricular element". We sought to design some kind of cartography of sensations related to the inhabited school spaces, considering dissonances and recurrences found in the analyzed material. This mapping process was not limited to the description of sensible experiences, but also included the relation between these sensations and the historical context in which they emerged.

According to Ricoeur (2007, p. 58), “the places 'remain' as inscriptions, monuments, potentially as documents, whereas memories transmitted solely through voices fly, just as the words fly”. It is easy to remember spaces, because “the act of inhabiting, […] constitutes, to this respect, the strongest human connection between a date and a place. The inhabited places are, par excellence, memorable. Because memories are so connected to them, the declarative memory is led to evoking them and describing them” (RICOEUR, 2007, p. 59).

1. Between Old and New: spaces in transformation

“Old”, “new”, "mystical space”, and “mysterious place” were some of the recurrent representations we found during the process of analysis of the interviews. Which sensations do these buildings provoke? What is the meaning of this dichotomy between “old” and “new”? How does it impact students? These are the questions pursued by this research…

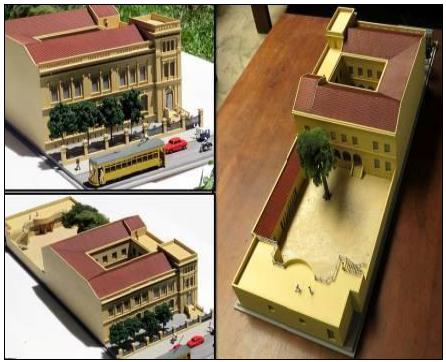

We start this discussion approaching Farroupilha School. Its first proper building was inaugurated in 1895; it symbolized the architecture produced in the period of Brazilian First Republic (Figure 1). Designed by the Fick Brothers3, according to Jacques and Ermel (2013), it was the first building produced exclusively for a school in Porto Alegre.

Between 1940 and 1950, the school board of the so-called Farroupilha Gymnasium and its sponsor had conducted many structural reforms to keep the building in operation.

In parallel to these reforms, came the idea to look for a new place so that the institution would leave the center of Porto Alegre. At that time, students called the building Old Mansion. About this construction, Martin comments,

We had, we have so many memories of the Mansion. The last ones concern a time it was kind of unstable. I remember when you walked on the floorboard, that was a wooden floor, and there was a wall that kind of shook as we ran on it. Then, going down the stairs running, that was forbidden […] (MARTIN, 2015, p. 8).

On the excerpt above, Martin comments that the building marked his experience as a student, and it probably also affected his school colleagues. This aspect refers to the collective reminiscing of a school group, with which individuals share some memories.

Having many memories does not mean that they are all about happy moments. For Martin, the perceptions about the space were not pleasant,

Like, I did not love the structure of the school, the building itself was not a thing that caused me a good impression. […] I thought it was kind of shady, the dark colors and the architecture of it, probably dark gray. The way it was internally, mainly, the wooden parts, the linings, they were not joyful. I hated to be imprisoned, my joy depended on the moment I went out, you know? When I had to create something. Inside you had to remain quiet, to pay attention, to repeat things (MARTIN, 2015, p. 11).

In Martin’s narrative, it is noticeable that the structure of the school did not please him. During the interview, this memory was recurrent, mainly due to the existence of a model of the house in which he lived during his childhood. For him, this dwelling was connected to the perspective of freedom, because it was spacious and, also, because it had a tree house. On the other hand, the school evoked a feeling of imprisonment on him.

His discourse is marked by speeches concerning his profession, architecture. In the year of 2015, for a High School reunion, he elaborated a model of Farroupilha School building. This fact by itself denotes how much the school was important in his life.

The miniature of Old Mansion presents an overview of the school facilities. It is noticeable the concern with the landscaping and the existence of a tram, cars and people in front of the façade. It is important to emphasize that Martin carried out a research on the history of the building to reconstruct it with greater resemblance.

The construction of the model also denotes a reconceptualization of the memory of the once inhabited space (Figure 3). According to Martin (2015), “working on the model, you live each corner you had there. […] [you] remind the localization of each room in which you have been, don’t you?”. We realize that, while constructing the narrative, the impression about the building being “old” assumed new meanings for him,

The classroom for the first year of High School was right on the corner of the patio in the back. Perhaps the impression in this first year had been better, because that was a building from 1923 it seems, it was way newer, then, probably. Its aspect was better than the old building. This was a good impression, I remember that in the first year, except for the teacher, I liked it, I liked the desks very much, with their light green color, which was (the color) of the building in the back. The desks were brand new, pretty "greenie". […] Dodgeball was also played up there in that patio. It was a pavement. I find even incredible a dude constructing a patio above the classrooms, at that time, and I do not remember seeing any infiltration in that flagstone, which is a complicated process, isn’t it? Until today, when you talk about waterproofing you give people the creeps. Because of the possibility of infiltration. […] You see, it was incredible the dudes did it then. […] (MARTIN, 2015, p. 12).

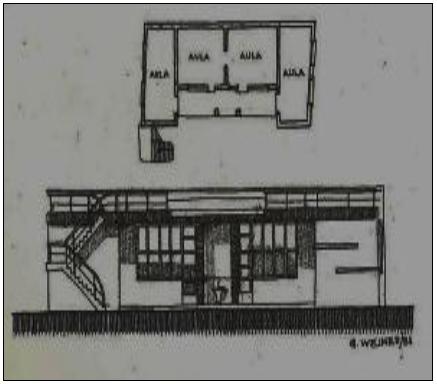

The construction mentioned by Martin was projected by the architect Julio Weise4, and its aesthetics was different if compared to the surrounding building. The structure had four classrooms and a patio on the upper floor (Figure 4). For Weimer (1994), this building can be considered one of the first Modern Architecture pieces in Porto Alegre.

Among the two columns in the façade, there was the phrase “Non Scholae Sed Vitae Discimus5”, a kind of motto of the institution. This inscription made the institutional discourse clear and possibly had the intention of diffusing it among the students. To Martin (2015), “there was some care, you know, it seems that it enhanced a kind of recognition of the act of teaching. It was something that seemed to be more valuable to us”. Another aspect that we observed in his story was the recurrence of the comparison with his profession, especially when commenting on the technologies used in the construction of this school building. Still on the precariousness of the building6, Martin commented that

The bathrooms were terrible. […] a little corridor, very small, a little entrance and an exit at the other corner. And this exit was quite narrow, it must have had about 80 cm. And the urinals were located on this side, there was only enough space to go through it. […] And outside there were the toilets, which were very dirty. […] Then if you had to use one of these facilities, you got very anxious. […] We held on not to go. […] (MARTIN, 2015, p. 12).

The men’s room was in the external patio. This feeling of repugnance produced in Martin is a memory which is difficult to be forgotten. In this sense, Izquierdo (2005), explains that stressful situations produce a release of adrenalin, and this substance has implications in the composition of memories. When analyzing his interview, we conclude that Martin’s memories express unpleasant emotions lived in the decade of 1950; his sensations represent what was dissonant in the narratives, since, for most of the interviewees, good memories emerged concerning the buildings categorized as “old”.

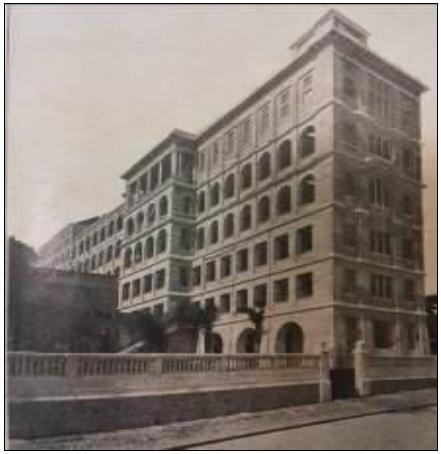

We move on to the discussion about Anchieta school. The manor of Duque de Caxias Avenue was the residence of the Fialho family, rented for the Jesuits in the decade of 1890. Since then, until the end of the decade of 1960, the building was adapted, and several reforms occurred, mainly to shelter the Boarding School and Elementary and High School.

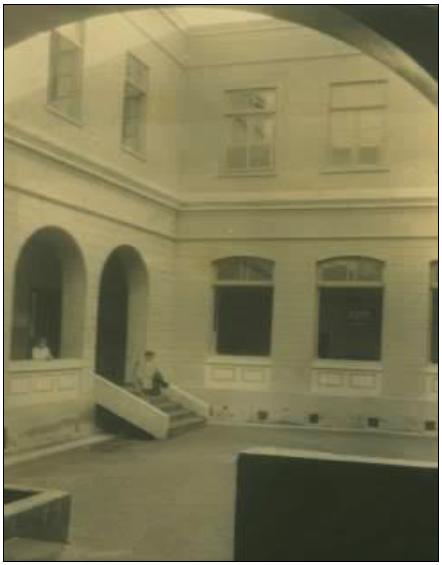

On Figure 5, we notice the façade of the manor and, on Figure 6, the last change of the school, in 1929, projected by the architect Vitorino Zani7. This change was important for the constitution of students’ memory, once it enabled the school to occupy a large area between Duque de Caxias Avenue and Fernando Machado Street. This location produced a nickname for the school: The Giant of the Duke (referring to Duque de Caxias Avenue). Fernando, when asked about the building, commented:

The building was an incredible piece of history because the classrooms had high ceiling. The windows were also high. The desks were long. And we felt very well and happy about that because the school was very good for us. They valued the tradition regarding religious education, in the communion, to attend mass, you know? […] Then many times I opened that door, because we had a feeling of affection towards religion. (FERNANDO, 2016, p. 2)

Fernando interlaces the memories of the school to the memories of religion. By doing so, it is possible to infer that the number of catholic symbols contributed for the construction of this feeling of affection. It can be noticed that the pedagogical activities, the religious education and the school space promoted this construction.

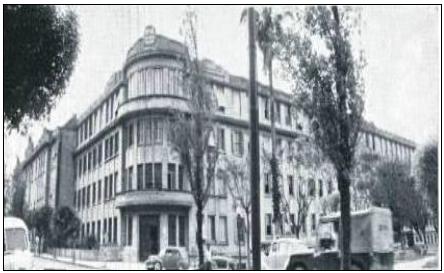

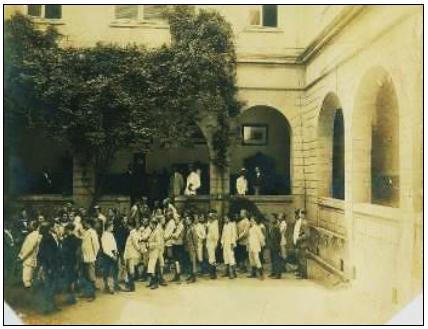

Following this confessional perspective, another catholic institution of education in this research is Rosario School. Its buildings were inaugurated in different temporalities and acquired their own meaning for those who studied there.

We can perceive, on this photo (Figure 7), the existence of three buildings of distinct temporalities and in different plans, which reminds the idea of palimpsest. On the foreground, there was the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), which occupied the same space of the school until the year of 1968. On the left corner, there was the building of the Primary Course, which was later demolished. On the right corner, there was the building that served as entrance for Elementary School and High School students, which had access to D. Sebastião square. On the memories of this complex school space, Sergio comments,

I loved the school building, there was a good aura. A kind of mysterious atmosphere, mainly in the oldest building, that one on the corner (SERGIO, 2016, p. 2).

Sergio’s narrative presents aspects concerning the materiality of Rosário School: old structure, presence of catholic symbols and the Marist Order. He states that, as a student, he felt sheltered by the presence of these elements in this school.

Regarding Farroupilha and Anchieta schools, the narratives evidence that there was a valuation of the so-called old buildings, mainly to reinforce students’ identity at a moment of abandonment of the previous structures for a headquarters change. It is possible to infer that this valuation had the intention to congregate the school community, so they could continue to attend the school in a new locality.

For the ones who attended Rosário School, there was not the necessity of reinforcing a sense of belonging towards the institution, since the school remained in the same place. It is important to point out, however, that, when PUCRS students left the institution, Rosário School’s students started to use the spaces previously occupied by the university.

In the analyzed discourses, we notice that the interviewees feel and recollect experiences in different ways, however we must consider the existence of a collective memory concerning these spaces.

2. Between monitoring and leisure: space as an educational element

The institutionalization of schools in European Modernity presupposed the existence of proper buildings and spaces for educational practices. By means of seclusion and monitoring, school architecture constituted artifices for the establishment of pedagogical practices (VARELA and ALVAREZ-URIA, 1993). When reflecting on control and punishment in school buildings, we consider Bentham’s panopticon model, used in schools, hospitals and prisons, analyzed by Foucault (1977). Many projects of buildings have been planned in this perspective, which implicates questions related to monitoring, punishments and discipline - all these themes emerged from the narratives of memory examined in this paper.

However, Viñao Frago (1998, p. 62) emphasizes that “Foucault’s model is insufficient for the understanding of different functions that a space has. If a space educates, it not only watches, punishes and controls”, but it also creates chances of having fun and learning. Escolano (2001, p. 26) considers spaces as “a kind of discourse that institutes in its materiality a system of values, such as order, discipline and monitoring, landmarks for sensorial and motor learning and a whole semiology that covers different aesthetic, cultural and also ideological symbols”.

This system of values changes in accordance with types of buildings. And these spaces produce different stimuli to students. In this regard, we analyze, through the lenses of the interviewees’ memories, the ways in which school buildings produced sensations in students, mainly, when it comes to aspects related to discipline and leisure. The first narrative which associates a school with a punitive value concerned Anchieta School. Fernando commented on the existence of a place called “buck”,

Buck was the following: let’s suppose a dude disturbed teachers a lot and did not want to study, he was always looking for problems. Then he had had to go to school in the afternoon and stay in a special room and remain there doing drills (FERNANDO, 2016, p. 3).

The kind of aforementioned penalty does not configure a prerogative of Anchieta School. The adoption of practices that compelled students to remain in certain places as a form of punishment was common in school institutions. What is discussed is how that room used for doing drills in the period opposite to regular classes became the “buck”, a punishment place that gained a proper name and evoked sad memories. Fernando (2016) considers the “buck” a place "feared by students", however he says he barely remembers it, because he never entered this room.

During the interview, he contacted a fellow worker and former classmate who met us. Fiore (2016), when inquired on punishments, remembers that the “buck” “was a darker room, compressed, different from the others which infused, much fear in students”. Fernando (2016) stated that “[I] found that it was a common classroom, but it also had this punishment purpose apart from class schedule”. Therefore, it is possible to question how everyone remembers a space reserved for punishment and discipline. This representation shows that memory is reconceptualized in distinct ways: Both interviewees constructed their proper versions of that place.

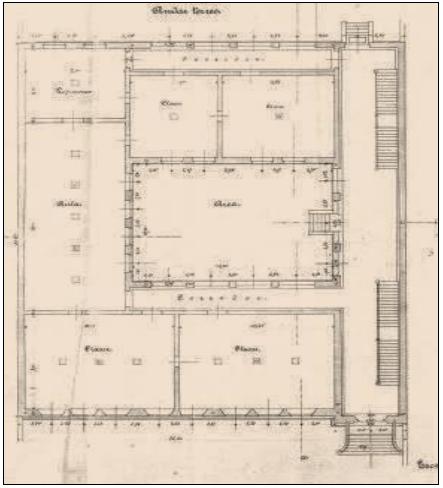

However, even though the narratives indicate that there was a specific room for application of punishments, we can say that all classrooms exerted a certain regulation of individuals, either through the organization of school furniture, the position of windows, the place reserved for the teachers, among other elements. On the other hand, it is important to emphasize that monitoring and discipline-related discourses are also manifested in other spaces, beyond classroom. An example is Farroupilha School, in which the structure of Old Mansion was projected with an internal patio which is similar to the one created by Bentham.

On Figure 8, we notice a model that is similar to the panoptic. To Foucault (1977, p. 166) this model “induces […] a conscientious and permanent state of visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power”. This logic considers that students must have knowledge of regulation mechanisms, although they do now know where exactly these mechanisms are. On the sensations evoked when remembering this subject, Martin commented,

The internal patio was wilder, more confined. I remember the internal patio, but then it was mostly the girls that had leisure time there. Ours was in general in the front patio, for some time, or at the back patio. There was a high patio which was located above one of the classrooms and there was the low patio, which was the one we used the most […] (MARTIN, 2015, p. 11).

Martin’s narrative indicates a practice of separation by gender. In this direction, it is important to remember that Farroupilha School became a mixed-gender school in the year of 1929; however, in the decade of 1950, there were still gender-based differences. Another example relates to the classroom spaces, in which girls and boys sat on opposite sides8. Such practices show that this school still segregated students by gender, making an adaptation in its coeducation discourse.

Beyond the regulation issue, Martin remembers the existence of two types of punishment associated to these spaces, especially in the internal patio.

There were punishments during recreation, which consisted in staying under the clock. Then, you had to stop at the corridor and go under the clock. If you were on the other patio, you had to stand against the wall.

[…] I do not remember being punished. But some of my classmates would stay under the clock sometimes. It was shaming, students would stay still, and their classmates would pass by, and life would go on. (MARTIN, 2015).

From the excerpt and considering Figure 10, it is possible to observe some punishment-related elements at the Old Mansion. Punishments were inflicted in large and crowded areas, probably with the intention of promoting visibility, by means of an intimidating message to other students that passed by.

Differently from the panoptic idealized by Bentham, due to the absence of an observation tower, the structure of Farroupilha School's internal patio still presented similarities with Bentham's concept. At this institution, we can replace the central tower by the internal part of the patio, in which teachers would remain, or by the windows of the upper floor, in which the school board was located.

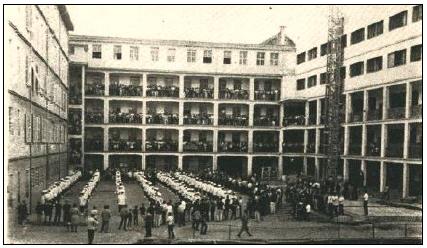

Moreover, other forms of control can be perceived on the other school buildings approached in this paper. At Rosário School, the successive buildings, in the decades of 1940, 1950 and 1960, eventually produced some kind of semi-panoptic, which enabled the school board to observe what was happening in the patios.

On this regard, Sergio said,

When there was a fight, the signal was that shout: “ôôô” and everybody would run and stand against the railings watching the fight that took place inside the patio. The fights were a show, an event. And the building facilitated it. It was converted in a ring (SERGIO, 2015, p. 5).

Sergio seemed happy and laughed a lot while remembering these episodes that, according to him, occurred with frequency. To us, the fact that these memories provoke laugh is strange. Perhaps it happens because these memories have been reconceptualized from the present perspective, and today they have a new meaning to Sergio. However, when comparing the buildings to a ring, it is possible to perceive, one more time, the extent to which the appropriation of school spaces can provide different and contrasting experiences, whether good or bad.

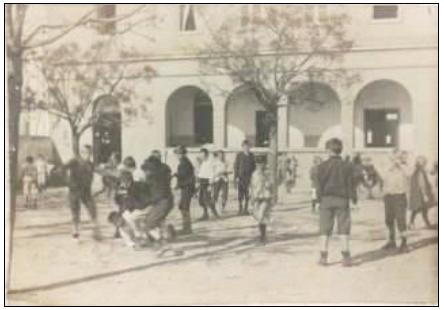

Still in this perspective, in the headquarters of American School, in the Rio Branco neighborhood (Figure 12), there was a structure that made this practice possible. Elaine addresses this topic:

And when I was a student at the primary teaching course […]. There was a specific space for classrooms. And inside, let’s assume there was a primary school classroom going on. And there, where today there is a screen, there was a glass that looked like a mirror from the inside and enabled people to see students from the outside. Thus, the outside area became some kind of observatory. So, my classmates and I, from the primary teaching course, would unnoticeably observe the primary students. The primary teaching course building was built after the construction of the main facility and was created to be an application school for the institution. (ELAINE, 2016, p. 6).

From this description, emerge other ways of monitoring. According to Elaine, constant observations were a school practice that controlled students and teachers. The primary teaching course building was inaugurated in 1952, under other pedagogical and urban conditions. Perhaps because the institution was instilled with New School ideals, its structure was planned this way. Elaine goes on:

When I was a literacy teacher, I knew that parents, other students and teachers could be there observing us. But it happened unnoticeably, in a more natural way. […] the building was designed with this purpose. Today it must have been modified, but at the time it was built that way (ELAINE, 2016, p. 3).

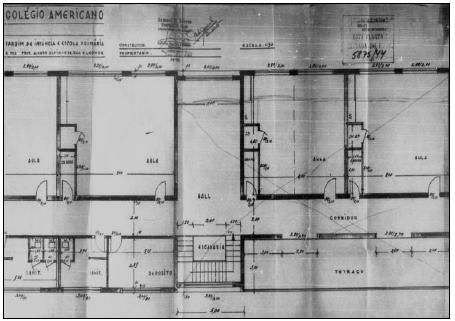

Considering the building blueprint (Figure 13), it is possible to notice that, in each classroom, there was an auxiliary door with an opening that enabled observers to see inside without being seen; this device was present in all the rooms. This model follows the same principles that Foucault analyzed, but without the idea of the panoptic; it produces the self-regulation principle, that is, individuals internalize rules of behavior in a system of constant monitoring. When remembering the school, these memories were evoked by Elaine, perhaps due to her profession and to the fact that, as a teacher, the considers school architecture as an element of school culture.

Many of these spatial conformations were not abandoned by the more recent architectural languages. In the new headquarters of Farroupilha School, inaugurated in 1962, there is a building created in accordance with the modern trends in vogue in the country (Figure 14). However, some years later, in 1976, another building was created in the same space (Figure 15). It has, in its interior, an adaptation of the panopticon. The structure presents an opening in its center that makes possible to see what happens in any side of the corridor. On the ground floor, there are the administrative boards of the school; on the second, there are classrooms; and on third, there are educational laboratories. The project was elaborated by the architect Robert Py Gomes da Silveira. On this building, we can see the central openings following the structure of panoptism. Moreover, there is a corridor that leads to the first constructed building, which was created in the 1960s.

But what does it mean to build a similar model to the panopticon that existed in the old headquarters of Farroupilha School? It is possible to infer that the recurrence of this architectural language indicates a conservative position of the school. At the same time in which the modernist architecture produces an atmosphere of freedom, in its interior, the control of students is reinforced. In this sense, Ana’s interview brought some considerations on the space of new Farroupilha:

We used to stay in the front patio, and there, on the track. […] At that time there was not the divided patio, nor the playground […] we used to stay in that part of the covered area, you know, there, there was the canteen there. We could make use of the canteen, you know? Then we used to hang out more that way and at the track, you know? I remember aunt Antheia watching us, she had a whistle. And then she whistled, and we formed a line. There was a proper place on the line for each one of us, and this organization was also used during civic activities. These events took place in front of the canteen (ANA, 2016, p. 7).

When describing the moments of the playtime, we perceive the extent to which Ana’s memories are marked by happy sensations, even when the topic was the monitoring of the assistant teacher, affectionately called Aunt Antheia. Ana highlighted that even the control exerted by her was very positive. Thinking about this, we perceive that, according to the interviewee, the teacher assistant exerted her duty of watching and, at the same time, she preserved her affectivity with students. Maybe this zeal facilitated her work, evoking good sensations in the memories of former-students.

Still regarding playtime, a first look at the Old Mansion enables one to think that in this building, due to its austere conformation, its lack of space and the constant monitoring within its facilities, students did not have access to many forms of leisure. Instead, Martin’s considerations bring other elements that enable us to relativize these questions:

So, these first memories… There was a fig tree too. Here in the back patio. Not a fig tree! Sorry, a Kapok. A Kapok. And it had a loft, a great root, a reentrance where students played with balls. [We] played “Cobrinha”, it’s a small ball game.

We used to play hunter in the playtime also, in which you shoot the ball and had to defend yourself (MARTIN, 2015).

Observing Figure 16 and Martin’s narrative, there are indications that the building is not only associated to monitoring and punishment actions. In this sense, the back patio is recollected as a local for leisure and not for monitoring. We can notice, therefore, the interviewee’s preference for this environment, in which, judging by what Martin says, there were multiple possibilities to create and to play.

Through the analysis of the four researched institutions, we observed that school spaces produce order and discipline. These values undergo modifications in accordance with pedagogical ideas from each time, as well as with structure changes and with individuals that attend to these institutions. At the same time in which control practices can infuse bad feelings, other practices evoke sensations dissociated from these watching and punishing actions; they evoke happy feelings from the moments of entertainment lived in those places.

Final remarks

In this paper, we analyzed school buildings and spaces through former-students’ memories, in order to understand that the history of sensibilities, in a wide perspective, relates to the respective individuals and to the senses that they construct. We tried to understand, from some questionings, which sensations school buildings and spaces evoke and how these discourses affect students.

We found that school environments are not isolated from the ones who attend to them. These spaces are projected by architects; however, who defines its functions are the individuals that use these spaces and remember them. Therefore, for this research, educational spaces have only become places after becoming part of students’ lives.

Throughout the research, it was necessary to reflect on the conceptualizations of school buildings. We conclude that, beyond sheltering educational practices, their main role is to be occupied by students. This act of inhabiting9 can produce sensations of confinement and immobilization of individuals; on the other hand, we observed a sense of support, because these institutions were also seen as places that welcome, protect students and become a reference for them; these feelings can surpass the years of schooling, and remain in their memories.

From patient listening, from reading sessions and from the analysis in search for past sensible experiences, we sought not make the mistake of trying to recover sensibilities; instead, we wanted to understand the way they escape from oblivion and the role school architecture plays in this production of senses.

After the inventory of former-students’ narratives, for this paper, two categories of analysis were constructed: “Between old and new: relations between students and school buildings”; “Between monitoring and leisure: school spaces as a curricular element”.

Regarding monitoring as a curricular element, initially we thought that architectural structures for the maintenance of these practices were inherent to the buildings designed before the decade of 1950. However, the examples discussed in this study, such as Farroupilha School’s building, from the decade of 1970, and Rosário School’s building, from the 1960s, show that other structures were created for the continuity of this controlling power in the buildings that had been constructed later. In this regard, it is important to mention that strategies of regulation enabled by architectural language are not homogeneous, once school spaces also enable other uses, as, for example, leisure.

The second topic of analysis relates to the notions of old and new that the evocation of these buildings produced in the imaginations of the ones who attended to them. Specifically, in this in case, there was a dissonance concerning Martin’s memories, who did not like Farroupilha School’s Old Mansion. For the others, the school old environment created a kind of perennial bond. Such a bond was important to promote the notion of identity in these former-students, mainly when these constructions were about to be abandoned. In this sense, several oral narratives were marked by the importance that these buildings had for their education and for the previous generations. This attribution of bond to the past can be considered one of the educational elements of identity.

Finally, the study demonstrated the ways in which students’ sensibilities were constructed by taking spaces as their evocator and as their scenario. This deeper conceptualization sensations related to of school spaces in the context of Porto Alegre was only possible because the interviewees reacted to discourses and stimuli evoked by school buildings, and, by experiencing these spaces, they also produced sensations that were reconceptualized as memories in palimpsest.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Milton José de. Alguma memória do futuro. Educ. Soc., Campinas, v. 31, n. 111, p. 501-515, abr.-jun. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302010000200011 [ Links ]

BRESSAN, Renan Gonçalves. Urbanização e escolarização nos estudos sobre instituições escolares. Rev. bras. hist. educ., Campinas-SP, v.13, n.3 (33), p. 29-56, set./dez. 2013. https://doi.org/10.4322/rbhe.2014.003 [ Links ]

CORBIN, Alain. O prazer do historiador. Entrevistador: Laurent Vidal. Revista Brasileira de História, São Paulo, v.25, n. 49, p. 11-31, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-01882005000100002 [ Links ]

DÓREA, Célia Rosângela. A arquitetura escolar como objeto de pesquisa em História da Educação. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, Brasil, n.49, p. 161-181, jul. /set. 2013. Editora UFPR. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40602013000300010 [ Links ]

ERMEL, Tatiane de Freitas. O “gigante do alto da bronze” : um estudo sobre o espaço e arquitetura escolar do Colégio Elementar Fernando Gomes em Porto Alegre/RS (1913 - 1930). 2011. 173 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação/PPGE, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2011. [ Links ]

ESCOLANO, Agustin. Arquitetura como programa. Espaço-escolar e currículo. IN: VIÑAO FRAGO, Antonio; ESCOLANO, Agustín. Currículo, Espaço e Subjetividade: a arquitetura como programa. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2001. [ Links ]

FARGE, Arlette. O sabor do arquivo. São Paulo: Edusp, 2009. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Vigiar e punir: o nascimento da prisão. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 1977. [ Links ]

GRUZINSKI, Serge. Por uma história das sensibilidades. In: PESAVENTO, Sandra Jatahy; LANGUE, Frédérique. (Orgs.). Sensibilidades na história: memórias singulares e identidades sociais. Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 2007. [ Links ]

HARTOG, François. Regimes de Historicidade: presentismo e experiências do tempo. Belo Horizonte: autêntica, 2014. [ Links ]

IZQUIERDO, Ivan. Questões sobre memória. São Leopoldo: Unisinos, 2005. [ Links ]

JACQUES, Alice Rigoni; ERMEL, Tatiane de Freitas. O VELHO CASARÃO: UM ESTUDO SOBRE O KNABENSCHULE DES DEUTSCHES HILFSVEREIN/COLÉGIO FARROUPILHA (1895-1962) In: BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara; JACQUES, Alice Rigoni; ALMEIDA, Dóris Bittencourt. (Orgs.) Do DeutscherHilfsverein ao Colégio Farroupilha: entre memórias e histórias (1858-2013). Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, 2013. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Cyro. Um menino vai para o colégio. Porto Alegre: movimento, 1992. [ Links ]

PESAVENTO, Sandra Jatahy; LANGUE, Frédérique. (Orgs.). Sensibilidades na história: memórias singulares e identidades sociais. Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 2007. [ Links ]

PESAVENTO, Sandra Jatahy. Cidades visíveis, cidades sensíveis, cidades imaginárias. Revista Brasileira de História, v. 27, n.53, jun. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-01882007000100002 [ Links ]

RICOEUR, Paul. A memória, a história, o esquecimento. Campinas: Unicamp, 2007. [ Links ]

VIÑAO FRAGO, Antonio. Do espaço escolar e da escola como lugar: propostas e questões. In: VIÑAO FRAGO, Antonio; ESCOLANO, Agustín. Currículo, Espaço e Subjetividade: a arquitetura como programa. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 1998. [ Links ]

WEIMER, Günter. Arquitetos e construtores no Rio Grande do Sul, 1892/1945. Santa Maria: UFSM, 2004. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

ANA LUISA. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2016/01/11. [ Links ]

ELAINE. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. 2016. Porto Alegre, 2016/04/12. [ Links ]

FERNANDO. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2016/03/07. [ Links ]

José Eduardo. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2016/03/07. [ Links ]

MARCOS. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2016/04/07. [ Links ]

MARTIN. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2015/12/10. [ Links ]

Nelly. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2015/03/09. [ Links ]

SERGIO. Interview with Lucas Grimaldi. Porto Alegre, 2016/02/25. [ Links ]

2Considering Escolano's studies (2001), we understand school architecture as a cultural product and not only as a curricular element.

6The school buildings, in the 19th century, did not incorporate ideals of hygiene and health. From the 20th century on, the priority in the building of schools would consist in aired and hygienical places. This is mainly due to the adaptation of the spaces, a problem which was solved with the construction and elaboration of proper places for teaching activities. On this topic, see Ermel (2011).

8This finding is supported by the analysis of a set of photographs that are kept in the school Memorial.

Received: February 20, 2019; Accepted: April 30, 2019

texto em

texto em