I am very interested in the work that historians do, but I want to do another one.

Michel Foucault

This article endeavors to describe and analyze the repercussions of Michel Foucault’s thoughts and, in particular, the possible uses of the genealogical procedure in Brazilian History of Education bibliographical production in the last two decades (1997-2017) published respectively in the three most influential Brazilian journals in the field, since their first publishing: História da Educação (1997), Revista Brasileira de História da Educação (2001) and Cadernos de História da Educação (2002).

Thus, we intend to continue and, at the same time, expand the initiative undertaken by José G. Gondra (2005), which had as object of analysis the same production until 2004 in two of the three journals that are here presented.

The argumentative path chosen here includes, first, presenting the notion of genealogy as conceived by the French thinker, in its connection to the Nietzschean theoretical framework. Furthermore, the debates between Foucault and the historians are briefly revisited in order to scrutinize the empirical data presented above.

Foucault and genealogy

The early 1970s witnessed, perhaps, the highest point in the relationship between Foucault and Nietzsche’s ideas, with the appearance of Nietzsche, genealogy, history (FOUCAULT, 2008a), which is the key to understand the so-called genealogical turn in the investigations conducted by the French author. In addition to this, there is a course on Nietzsche and genealogy given in Vincennes in 1969, as well as his inaugural course at the Collège de France (FOUCAULT, 2018), which took place between December 1970 and March of the following year, in which the philosophical paradigms defended by Aristotle were contrasted to those formulated by Nietzsche. For Foucault (apud DEFERT, 2014, p. 26), it means the fascination with “a morphology of the will to know in European civilization that has been set aside in favor of an analysis of the will to power”, as he revealed in a letter of 1967, shortly before he finished writing of The archaeology of knowledge (FOUCAULT, 2014).

The way by which Foucault justified his interest in the German philosopher was due to a long relationship, which began in the 1950s as a result of contact with Georges Bataille’s work, having been consecutively replaced throughout Foucault’s research. In 1953 Foucault had taught a course in Lille, addressing the philosopher in some of the classes. In 1966, he became responsible, along with Deleuze, for the French edition of Nietzsche’s complete works. His relationship with the philosopher, however, would not be restricted to the intellectual realm. Still in 1966, Foucault settled in a Tunisian coastal village, as described by Daniel Defert (2014, p. 23), “[...] striving, according to Nietzsche’s vote, to become a little more Greek, sporty, tanned, ascetic, he inaugurates a new stylization of his existence”.

If, at the time, his interest in Nietzsche was about how writing was linked to madness (FOUCAULT, 2014b) as well as the intention to elaborate a history of reason (FOUCAULT, 2008b), such interest was later displaced towards the investigation of the problems related to the truth, that is, to discourses taken as truth in their connection with forms of self-reflexivity cultivated by individuals.

The references to Nietzsche, in Foucault’s works, concentrated in the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s - in which the debates about the will to know would be resumed in 1973 in the course Truth and juridical forms (2001) given in Brazil - decreased in the following years; fact recognized by Foucault himself (2008b) in 1983, when he declared that he had not read Nietzsche in several years. Paradoxically, the disappearance of the German philosopher in Foucault’s texts took place when the courses and books associated directly with the French genealogical endeavours came to light, constituting the so-called last phase of the thinker, which began with the course On the government of the living (FOUCAULT, 2014a).

The apparent mismatch between the rarefaction of references to Nietzsche and the incorporation of the genealogical framework into the procedures adopted by Foucault were the subject of the reflections undertaken by Vânia Dutra de Azeredo (2014). In order to resolve such paradox, she proposed that it would be possible to divide the Collège de France professor’s thought into two moments regarding the interactions with the Nietzschean legacy.

They [the writings on Nietzsche] were followed by Foucault´s silence as a commentator in favor of his growth as a philosopher, through a change of method that abandons the work of interpreting texts. That is, Nietzsche treated as an instrument of thought. From a certain point on, Foucault uses Nietzsche to think about his own philosophical questions and, as a result, begins to realize a genealogy of moral. (AZEREDO, 2014, p. 58).

Taking Nietzsche, Freud, Marx (FOUCAULT, 2008d), 1967, and Nietzsche, genealogy, history (FOUCAULT, 2008a), 1971, as object of analysis, Azeredo situates, in the interval that separates the two texts, the turning point between the Foucault of interpretation and the one of genealogy , attributing to the second one a procedure guided by Nietzsche.

It is a common belief, among those interested in the Foucauldian trajectory, the argument that states that Foucauldian genealogy, which has the 1971 text as a turning point, is derived from Nietzsche´s perspective. Among them, Alexandre Filordi de Carvalho (2012) highlights the similarities between Foucault’s genealogical operation and Nietzsche’s, taking him in continuation of the latter´s steps.

Assuming himself openly as a reader of Nietzsche and, moreover, drawing on him as an esteemed interlocutor and critical expoent of the conditions by which man today is (re)inventing himself - the celebrated face of the man drawn on the seashore, about to fade - Foucault will define the methodological conditions of his philosophical endeavor: to make philosophy by making history, and from this making philosophy itself (CARVALHO, 2012, p. 225).

Scarlett Marton (1985), recognizing that in Foucault’s ideas there is certain illumination of Nietzsche’s theories, is concerned, however, with the aspects of the Foucault´s ideas that seem to operate against the philosophy of the German thinker, especially with regard to the lack of the cosmological character in the Nietzschean theory of forces - based, according to Carvalho, on the thematization of life as a plurality of forces. Such divergence, however, is explained by Foucault’s endeavor on giving centrality to the relationship between genealogy and history, not taking in to account any thoughts about the inorganic world. Thus, both sides of Foucauldian genealogy - one philosophical and the other historiographical - would define the particularity of his effort (MARTON, 1985).

Following the hypothesis formulated by Marton, we will next focus on the relationship between history and genealogy in Foucault, in order to situate the main reverberations of his thought in the historiographical field. For this, we are guided by Paul Veyne’s considerations in Foucault revolutionizes history, which demarcate the context of reception of Foucauldian genealogy among historians.

Is Foucault still a historian? There is no true or false answer to this question, for history itself is one of those false natural objects: it is what it is made of it, it has not ceased to change, it does not foresee an eternal horizon: what Foucault does will be called history, and at the same time it will be history, if historians get hold of the gift he has given them and do not regard it as green grapes. (VEYNE, 1982, p. 181).

Foucault, history and historians

Veyne’s considerations on historians’ view of Foucault validate the idea of a link between history and philosophy, allowing us to foresee the struggle in Foucault’s relationship with most historians of his day. This is because the notion of genealogy evoked by the thinker contrasts with the linearity of historiographical narratives, which, according to him, would be responsible for an essentialist relation between the present and the past. Based on the investigation of the conditions of provenience and emergence of a given event - rather than a search for its origin; the latter figuring as a notion associated with a teleological conception of history, which Foucault neglects - the genealogist would come across not with an essential secret of things, but with the fact that these “[...] are without essence or that their essence was built piece by piece from figures that were foreign to them “ (FOUCAULT, 2008a, p. 262).

This premise gets clearer when the notion of ultimate individual difference, employed by Veyne (2009) to describe the Foucauldian point of view, is considered. This idea describes an effort of perception capable of stripping the historical objects of his historiographical apparel. In other words, it is an effort to analyze the knowledge itself around these objects, turned, then, into objectivations. Taking sexuality as an example, it would be necessary, according to such way of thinking, to give up considering this theme as something that would have gone through time invariably. Rather, it is a matter of circumscribing the discontinuous experiences into which sexual practices have been inscribed: Greco-Roman aphrodisia, medieval flesh, and modern sexuality respectively - three practical domains not coincident with each other.

As Philippe Artières (2016, p. 387) characterizes, “[...] Foucault invites to shortcuts. He loves to surpass the great partitions operated by historical discipline. No Renaissance or Revolution. He forces us to detach ourselves from our historical categories.”

Contrary to the use of certain analytical notions raised to the status of universal categories - such as society, religion or even the subject - usually employed not only by historians, but also in other fields of humanistic knowledge, Foucault (2008c, p. 5) choose to leave

[...] the decision, both theoretical and methodological, which consists in saying: suppose that universals do not exist; and at this point I ask the question to the history and the historians: how can you write history if you do not admit a priori that something like the state, the society, the sovereign, the subject exists?

As a result, emerges the defense of a nominalism (FOUCAULT, 2008c), according to which the past that appears to us today is in accordance with the veridictive rules defined by the experience of the present itself. To make a genealogy, then, would be to undertake a critical history of the present, as in opposition to the universals that the same present believes are related to former times.

In this way, it would be possible to separate history from its own historiographical discursivity, not by taking it as inappropriate, but by understanding that the categories it often uses, even those treated as operational (culture and economy, for example), would concern only one of several modes of reference to past experiences. Thus, the possibility of an unrestricted use of the historial object - perhaps a more precise designation to distinguish it from the usual meaning operated by historiography -, as Foucault carried out in his investigations.

The unstable acceptance of the ideas presented in Madness and civilization [1958] and The orders of things [1966] among historians of the 1960s and 1970s would eventually frustrate Foucault’s expectations, although some of the New History adherents - Fernand Braudel and Robert Mandrou, for example - have reputed them as correlative to what was produced within the History of Mentalities (VEYNE, 2009).

For others contemporary thinkers, especially those tributaries of Marxism - like Jean Paul Sartre - Foucault’s formulations were out of place, given the presumed absence of general explanatory schemes. Above all, the belief that Foucauldian genealogy had an “[...] objective limitation of the field of instruments” of analysis (SARTRE, 1978, p. 172), would result, according Sartre, in an indisposition with historiography itself. On the other hand, historians like Jacques Leonard directed critics towards Foucault’s work, based on an almost opposite argument: that he sought to apply a generalizing philosophy to history, since he was only a philosopher - definition often used to undermine their contributions to the historiographic field (O’BRIEN, 1995). Many of those who subscribed to Leonard’s criticism did so based on the certainty that the thinker, foreign to the historiographic field, joined the structuralist current or the linguistic turn, losing sight of the diachronism of historical events or even their preponderance over language. They understood that “[...] Foucault reifies an instance that escapes human action and historical explanation, which privileges the cuts and structures over continuities or evolutions, which is not interested in the social... In addition, the term ‘discourse’ created much confusion” (VEYNE, 1982, p. 151).

For Veyne (1982), this association also derives, at least in part, from the assumption that Foucault would be a relativist, capable of questioning the reality of a concrete phenomenon such as madness. According to Carlo Ginzburg (1987), another historian refractory to Foucault’s propositions, Foucault was mistaken in refusing to interpret the judicial and psychiatric documents he addressed, assuming, in contrast to Microhistory, a greater concern towards the processes of exclusion than to the excluded. Agreeing with Edward P. Thompson, for whom there would be “[...] much of a charlatan in Foucault” (GINZBURG apud PALLARES-BURKE, 2000, p. 305), the Italian negates the originality of Foucault’s work, reputing it so only as an appendix to Nietzsche: a footnote, in his terms.

Among other historians of his time, however, Foucault found supporters such as Philippe Ariès, Michelle Perrot, Georges Duby, and Jacques Le Goff (VEYNE, 2009). For the latter, Foucault had indeed contributed to the crisis of the historical discipline; a contribution that would not necessarily be negative, as it would have allowed some questioning of the triumphant truths of the field (LE GOFF 2003). Hence the defense that Foucault’s criticism would not constitute a project of degradation of professional historiography, but an effort to strengthen it, calling into question some of its unreflected premises.

The acceptance of Foucault’s work among historians has increased significantly with the publication in France of Foucault revolutionizes history in 1978, in which he is treated by Veyne (1982, p. 151) as “[...] the consummated historian, the finalization of the history”. Michel de Certeau’s reading in 1980 also contributed to this: a compliment to the Foucauldian approach regarding the practical character of the speeches, highlighting the fact that, with him, “[...] the theorizing operation is there on the edge of the terrain where it normally functions, like a car by a cliff-top” (1994, p. 131).

Still in the 1980s, another type of critics of Foucault’s thought would come from the so-called New Cultural History by Robert Darnton, Roger Chartier and others, which sought to assign centrality to cultural practices in the face of economic and social transformations, without taking them as totally detached from each other. This would create conditions for the development of a history of culture that wasn’t explained through social history, yet it could contemplate the links between cultural practices and political relations.

Beyond the enthusiasts or detractors of Foucault’s work, Roger Chartier (2002, p. 126) is categorical in asking:

Should Foucault be opposed by Foucault and his work be placed in the very categories which he considered powerless to adequately account for the discourses? Or should his work be subjected to the procedures of critical and genealogical analysis that he proposed and, consequently, nullify what allows to delimit its unity and singularity? Foucault was undoubtedly delighted to have fabricated this “small (and perhaps hateful) machinery” which plants restlessness within the very commentary that intends to tell the meaning of the work.

It is a fact that the main effect of Foucault’s legacy seems to be at least a pronounced concern about the tacit premises in the ways of researching in different fields of knowledge. Safeguarding the particularities of each one, this is also what is at issue here in relation to the Brazilian History of Education. Has Foucauldian thought impacted researchers in the field? If so, what is the nature and the amount of this impact?

Foucault and Brazilian Research

The presence of Foucault’s ideas in Brazilian academic debates confuses itself, in its early days, with the relative attendance of his visits to Brazil between 1965 and 1976 (RODRIGUES, 2011). In addition to his works, then little was translated into Portuguese, also contributed to the philosophical, medical and psychiatric debates of the time, the audiovisual records of the seminars and round tables which he participated in Brazilian soil. Highlight to the conferences that took place at PUC-RJ, entitled Truth and juridical forms (FOUCAULT, 2001).

It was in this context that the first Brazilian studies of declared Foucauldian inspiration emerged, such as Damnation of the rule (MACHADO et al., 1977) and Medical order and family rule (COSTA, 1979). In the same decade, the first Portuguese translations of Foucault’s studies were published: Discipline and punish in 1977 and Microphysics of power in 1979.

Such publications contributed to the further spread of Foucauldian theorizations in different fields of knowledge. Among historians, as explained by Margareth Rago (1993, p. 125), such incidence occurred in the scenario of Brazilian redemocratization, in “[...] a moment of intense social contestation and the dazzling of new possibilities, at the turn of the 1970s to the 1980s”. For Rago this fact helps to explain why the first studies of history based on Foucault were “[...] strongly marked by the notions of discipline, micropolitics, normatization of gestures, showing, in their own way, the production of the individual by the meshes of power” (RAGO, 1993, p. 130). The focus on theorizations about the power-knowledge relations and their subjective effects would be responsible, moreover, for the association operated by Brazilian historians between Foucault’s ideas and Edward P. Thompson’s heterodox Marxism; association that would be, for Rago, inscribed in the list of impossible marriages starred by Foucault in the historiographical thought of the period.

In the educational field, according to Julio G. Aquino (2013) the diffusion of Foucault’s thought refers initially to the publication of two collections of studies organized respectively by Tomaz Tadeu da Silva (1994) and Alfredo Veiga-Neto (1995). Such endeavors were marked by criticism directed to the notions of autonomous subject and to the effects of truth/power correlated to the modalities of knowledge, at the time, prevailing in the pedagogical field (PARAÍSO, 2004).

If, in the 1990s, the Foucauldian current of studies was already much more vigorous than in the mid-1970s, another study by Aquino (2018) reveals that its importance in Brazilian academic debates has not stopped growing in the last two decades. However, one could say there is a kind of inertial appropriation of the thinker, a catechism in Silva’s (2002) view, seems to be equally recurrent, resulting in Foucault’s own capture in reiterative comment.

Regarding the History of Education, for Inés Dussel (2004, p. 63), an Argentine researcher whose ideas widespread among Brazilian education historians, one of the explanations for the prestige of Foucauldian ideas would lie in the renewing potential of his writings, since through them it would be possible to reflect “[...] about the contingency of our school forms, our ways of thinking about knowledge, our ways of transmitting it and the injustices that populate even our best pedagogical dreams”. Gondra (2005), evaluating Foucault’s appropriations in the historical-educational field, understands them as a search by the History of Education for autonomy in relation to the historiographic field, with a view to the constitution of their own objects and procedures. In this sense, Foucault’s historical procedure, by distinguishing itself from classical historiography, would be presented as an alternative to studies interested in a new epistemological identity.

Diverging from Gondra’s conclusion, Luciano Faria Filho and Diana G. Vidal (2003, p. 60) point to a use of Foucault and other foreign names by education historians driven not by the demand to move away from history, but rather to “[...] mark their belonging to the community of historians, and [...] identify their research with procedures specific to historiography “. For Faria Filho and Vidal the demand for a greater theoretical basis for historical-educational research would make Foucault’s type of conceptual contribution an important aspect to be observed. For these authors, such a movement would come from the discomfort with the presumed subservience of historical-educational studies to the pedagogical imperatives, as well as to philosophical approaches, which would have prevailed, according to the authors, in education research undertaken until the 1980s.

These conclusions were based on the analysis of Miriam J. Warde (1984) who, concurrently with Jorge Nagle (1984), had highlighted the theoretical fragility of most of the researches in History of Education conducted so far, defending a greater interaction with the social sciences, especially History, as a means of strengthening the historical-educational field. Warde (1984) hoped that it would be possible to overcome the presentism and pragmatism characteristic of such investigations, as well as their propositional aspect, favoring more analytical researches.

In the following decades, Warde’s and Nagle’s views on the incipience of theoretical debates in the historical-educational field were endorsed by other researchers, also defending a larger dialogue in between education historians and their pairs in other fields. (BONTEMPI JUNIOR; TOLEDO, 1993; SAVIANI, 1998). In this scenario, a series of thinkers foreign to the historical-educational domains, historians or not, would have been incorporated into the field, being Foucault, at the time, among the five most cited in these studies (FARIA FILHO; VIDAL, 2003).

However, for other researchers of History of Education who inherited the negative view of part of historiography about the “postmodern paradigm” (CARDOSO, 1994), from which Foucault was supposed to be tributary, the presence of the French thinker in historical-educational studies must be viewed more as a danger than as an alternative to field inflections. This was the case of Dermeval Saviani (1998, p. 16), for whom Foucault was part of a trend whose spread in the historical-educational field would need to be contained, in favor of “[...] the concern to investigate the History of Education through society’s mediation, which implies the search for a global understanding of education in its development “.

The impression of Foucault as an outcast in historiographical debates would not cease in later years, as Durval Albuquerque Júnior (2004, p. 97) attests:

All his work in the historiographical field is disqualified with half a dozen opinions and guesses, almost always directed to his person and not to his thought. [...] Foucault is always treated as an invader of the field, as someone who even wanted to put an end to history, even though he devoted his whole life to it and proved to be a creative practitioner of our metier, stimulating a wide production in the area.

Such reverberations, four decades after Veyne’s position on the revolutionary character of Foucault studies, indicate that the theoretical clashes concerning the encounter between Foucault and history have not ceased. Transposed to the field of the History of Education, such divergences demonstrate, in our view, the need to take into account the implications of the Foucauldian reference in the studies conducted in this area and, in particular, the theoretical-methodological elements related to it that were unstabilized or otherwise reinforced by Foucault’s presence.

Foucault and the Brazilian research in History of Education

Interested in the material dimension of Brazilian historical-educational researches that mobilized Foucauldian ideas, we studied the production published on the three main Brazilian journals devoted to the History of Education. We believe that is a sufficiently comprehensive display of what has taken place in the field, in spite of the fact that such selection does not cover the full spectrum of researches, since textual production is equally distributed among several other non-specific journals from the educational field.

A total of 111 articles were selected, which included some Foucauldian work in their references, namely: História da Educação: 36 articles; Revista Brasileira de História da Educação: 36; and Cadernos de História da Educação: 39. The articles of foreign authors in the three journals were excluded, since the scope of this work turned only to the production of Brazilian researchers.

After this, we distinguished those texts in which an effective use of Foucault’s ideas was made; differently, therefore, from a contingent use of them. Effective use describes a more systematic and articulated appropriation of the author to the argument itself, and may take place at different levels (which will be discussed later), while contingent use is defined as a non-substantive appropriation - and often only incidental and/or surgical - of the ideas of the author cited, without apparent relation to the predominant theoretical framework employed in the text.

Thus, 42 texts which content pointed to a stricter relation with Foucauldian thought were selected: 15 in História da Educação; 09 in Revista Brasileira de História da Educação; 18 in Cadernos de História da Educação. It should be pointed that, despite having a smaller number of published numbers2, the last journal presented twice as much articles as Revista Brasileira de História da Educação. The texts that presented an effective use of Foucauldian ideas are:

In História da Educação:

POSSAMAI, Zita Rosane. The spelling of bodies in urban space: the students in the biography album of a city, Porto Alegre, 1940. 2015.

WITCHS, Pedro Henrique; LOPES, Maura Corcini. Deaf education and linguistic governmentality in the Estado Novo (Brazil, 1934-1948). 2015

ALMEIDA, Cíntia Borges de; NEVES, Dimas Santana Souza; GONDRA, José Gonçalves. Compulsory education: “It is prudent to wait for the time to take the necessary medicine”. 2012

BORGES, Angelica. For a rigorous and illustrated discipline: the Inspection in the Empire Capital. 2012

SOUZA, Maria Zélia Maia from. Government of children: the João Alfredo Professional Institute (1910-1933). 2012

FISCHER, Beatriz T. Daudt. Revista do Ensino/RS and Maria de Lourdes Gastal: two stories in connection. 2010

TEIVE, Gladys Mary Ghizoni. School group and production of the modern subject: a study on the curriculum and school culture of the first Santa Catarina school groups (1911-1935). 2009

GONDRA, José Gonçalves. Between the cure and the doctor: hygiene, teaching and schooling in Imperial Brazil. 2007

SILVA, Nilce da. From the “French Revolution” to the “21st Century”: some notes about the French educational system. 2007

CARVALHO, Rodrigo Saballa de. The emergence of early childhood education institutions. 2006

FISCHER, Beatriz T. Daudt. Nilce Lea’s paper boxes: memories and writings of a simple teacher? 2005

ROCHA, Cristianne Maria Famer. School spaces: productive modernizations. 2000

GAMA, Zacarias Jaegger; GONDRA, José Gonçalves. A strategy for curriculum unification “The Statutes of Public Schools of Primary Education” (Rio de Janeiro: 1865). 1999

FISCHER, Beatriz Daudt. Foucault and life stories: approximations and so forth. 1997

STEPHANOU, Maria. Educational practices of social medicine: doctors become educators. 1997

In Revista Brasileira de História da Educação:

SANTOS, Flavio Tito Cundari da Rocha; AQUINO, Julio Groppa. The ‘Letters of Formation’ by Mário de Andrade (1924-1945) and their educational power. 2017

MENEZES, Antonio Basílio Novaes Thomaz de; SILVA, Juliana da Rocha e. School education that disciplinates and normalizes: Luiz Antonio dos Santos Lima and the corrective measures contained in Mental Hygiene and Education (1927). 2016

CARVALHO, Eliane Vianey de; ABREU JUNIOR, Laerthe de Moraes. The fight against “race degeneration”: educational discourse for the population in Minas Gerais public health legislation in 1927. 2015.

CONCEIÇÃO, Joaquim Tavares da. ‘Cruel vices’ medical campaign to combat masturbation and homosexuality among boarding school boarders (1845-1927). 2015

VIVIANI, Luciana Maria. Educational Biology: exercise and innovative proposals in a São Paulo educational journal (1938-1941). 2015

GUIMARÃES, Paula Cristina David. “Everything is good for those who need everything”: the speeches on schooling of poor childhood, present in the Revista do Ensino, from Minas Gerais (1925-1930). 2013

RITO, Marcelo; AQUINO, Julio Groppa. Nature, childhood and science in Brazil from the 1920s/30s: modern pedagogy and the Bibliotheca de Educação. 2012

NEVES, Dimas Santana Souza. Power and school culture in the First Republic in Mato Grosso. 2007

PAULILO, André. The reverse of norms: indolent, lazy, reckless and other school types. 2007

In Cadernos de História da Educação:

RIPE, Fernando. “If you are careless, if you are helpless, your child may be lost forever”: vigilance and punishment in an 18th century Portuguese Manual on Social Behavior. 2017

CASTRO, Cesar Augusto; CASTELLANOS, Samuel Luis Velazquez. The diseases and the control of the corporal desires of the boys collected in educational institutions of Maranhão in the eight hundred. 2016

GUIDO, Humberto. The social history of children: subsidies for the historiographic research of childhood (1530-1599). 2015

ELIAS, Aluizio Ferreira; RESENDE, Haroldo de. The adjusted child: aspects of Dante Moreira Leite’s thinking about Brazilian urban childhood. 2014

GONÇALVES NETO, Wenceslau. “Christian youth education”: regulation of school life in Catholic schools of Minas Gerais (1863-1911). 2014

HICKMANN, Roseli Inês. Of the declared rights: a (re) told story about the childhood of rights. 2014

CALDEIRA-MACHADO, Sandra Maria; BICCAS, Maurilane de Souza; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de. Educational statistics and schooling process in Brazil: implications. 2013

CARDOSO, Maurício Estevam. For a cultural history of education: possibilities of approaches. 2011

GUIMARÃES, Paula Cristina David. The medical discourse on education of poor childhood, published by the Minas Gerais Revista do Ensino (1925-1930). 2011

LIMA, Solyane Silveira; BERGER, Miguel André. The Amélia Leite Maternal House (1947-1970): an educational institution for the protection of motherhood and childhood. 2011

RESENDE, Haroldo de. Watch, punish and educate: the prison’s “educational system”. 2010

ABREU JUNIOR, Laerthe; FERNANDES, Michele Longatti; NEVES, Ellen Pereira. On the outskirts of the city, on the fringes of educational processes: memories of school experiences of residents of the São Geraldo neighborhood in São João Del-Rei. 2008

DURÃES, Sara Jane Alves; AGUIAR, Fatima Rita Santana. The Minas Gerais school groups as a place for discipline and body hygiene. 2008

MANKE, Lisiane Sias; PERES, Eliane. The proof books as devices of control of the teaching work: a contribution to the history of the teaching profession. 2008

ALVES FILHO, Eloy; SALCIDES, Arlete Maria Feijó. Advantages of literacy from the perspective of adults living in rural areas of Brazil and Portugal. 2007

ALMEIDA, Maria de Fátima Ramos de. Brazilian educational policy in the 1990s: a disservice to citizenship. 2005

BERGER, Miguel André. Church X education: the role of the Nossa Senhora de Lourdes college in the formation of the female elite. 2004

TOFOLI, Therezinha Elizabeth. Female education at Adamantina-SP Madre Clélia School. 2004

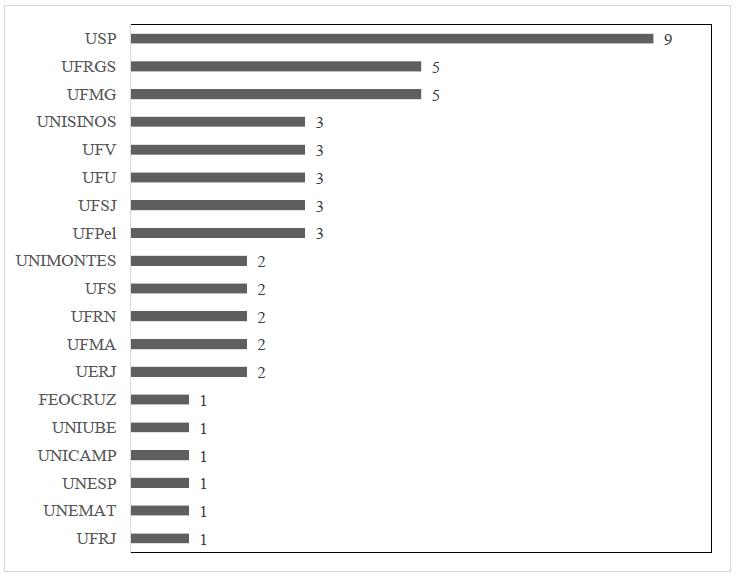

At all, there are 50 different authors linked in the selected texts, 42 of them appearing only once. Among the others, two authors appeared three times: Beatriz T. Daudt Fischer and José Gonçalves Gondra. Another six, twice: Dimas Santana Souza Neves; Haroldo de Resende; Julio Groppa Aquino; Laerthe de Moraes Abreu Junior; Miguel André Berger; and Paula Cristina David Guimarães. The 19 institutions to which the 50 authors have declared their affiliation are as follows:

Regarding the temporal distribution of the articles, the 21 years between 1997 and 2017 were subdivided into three ranges: the period 1997-2003 had only four published texts (10%); between 2004 and 2010, there were 16 texts (38%), while 22 (52%) were published in the later years (2011-2017). A demonstration of a growing interest in Foucault’s legacy? This could not be categorically stated as it will be shown.

Regarding the use of Foucauldian ideas, a first element considered was the effective references to the thinker’s work, which were divided between the books, the courses and sparse texts. In this sense, books consist of the most visited textual support by researchers. And only five of all of Foucault’s works were referenced. Discipline and punish (in 19 of 42 texts); The archaeology of knowledge (in 11); The order of discourse (in six); History of sexuality, Vol. 1 (in six); History of sexuality, Vol. 2 (in two); and History of sexuality, Vol. 3 (in one text only).

Secondly, the sparse texts stand out. It is the case of Microphysics of power (19 times); Sayings and writings (five); What is an author? (four); the texts inserted in Michel Foucault: beyond structuralism and hermeneutics (three); Truth and juridical forms (three), the texts contained in the Spanish editions: Las Redes del Poder (one) and Tecnologías del yo (one).

The courses constitute the least visited textual support by researchers. The following were mentioned: “Society must be defended” (in six texts); Security, territory, population (in four), The Government of self and others (in two); The birth of biopolitics (in two); Psychiatric power (in one); Abnormal (in one); The hermeneutics of the subject (in one); The courage of truth (in one). The Courses Summary at the Collège de France has been quoted twice.

Focusing the argumentative scope of each of the 42 selected articles, the analyzed materials where subdivided into: official documents (in 11 studies); periodicals and books (nine); testimonials (seven); documents from specific institutions (five); medical writings (five); correspondence and personal files (three); iconographic material ( three); school supplies (one). In the case of theoretical essays (five), works by educational theorists and thinkers of other fields were mobilized.

The predominant Foucauldian theoretical ideas that are used in the articles are: discipline (19 times); discourse (nine); governmentality (nine); biopolitics (five) archeology/archeogenealogy (three); genealogy (three); power (two); subjectivation (two); truth (two); archive (one); focal points of experience (one); author function (one).

Finally, there are two operational differences worth mentioning:

1) The texts in which the notion of genealogy is generically evoked in the theoretical-methodological argumentation. These are four occurrences:

CARDOSO, Maurício Estevam. For a cultural history of education: possibilities of approaches. Cadernos de História da Educação, 2011;

CARVALHO, Rodrigo Saballa from. The emergence of early childhood education institutions. História da Educação, 2006.

FISCHER, Beatriz T. Daudt. Revista de Ensino/RS and Maria de Lourdes Gastal: two stories in connection. History of Education, 2010;

FISCHER, Beatriz Daudt. Foucault and life stories: approximations and so forth. História da Educação, 1997.

2) The texts in which Foucault appears longitudinally in the argumentation, covering from the thematic circumscription of the chosen problem, passing through the methodological support, until the discussion of the results themselves. In this case, only three of the 42 texts presented such constancy:

CARVALHO, Rodrigo Saballa de. The emergence of early childhood education institutions. História da Educação, 2006.

FISCHER, Beatriz Daudt. Foucault and life stories: approximations and so forth. História da Educação, 1997;

RESENDE, Haroldo de. Discilpine, punish and educate: the prison’s “educational system”. Cadernos de História da Educação, 2010.

Conclusion

Interested both to the articles as a whole and to the specificities of each one - in order to show simultaneous, however decentralized, movements -, the investigation of the elected analytical corpus did not intend to make any kind of comparison between research as was practiced by Foucault and the intentions of Brazilian education historians. Such a judgmental attitude would, certainly, entail the belief that these studies were less important when compared with Foucault’s work, or, more radically, it would direct us to the risky investigation of pieces trying to replicate - successfully or not, it doesn’t matter - Foucault’s analytical parameters about some investigative object other than those he has studied.

Instead, we admit the power of the recreating circulation of discourses, in the wake of which the uses of a given author and their respective developments are reinvented each time, thus having a range of undetermined effects, since they are not necessarily coincident with each other, nor with a supposed authorial unity. In short, we urge ourselves, like Foucault himself did, to refuse any author circumstances as a foundation.

Even refracting any effort of authorial mimesis, however, a noteworthy detail: none of the articles mobilized had Nietzsche, genealogy, history among its references. The presumptive discretion or, at the very least, the researchers’ abstention from the genealogist Foucault leads, it seems to us, to one of the following conclusions: either the genealogical operation would have been entrenched in the studies to the point of leaving no authorial trace, or the analyzes carried out, still based on sedimented historiographical procedures, using only sparse elements of Foucauldian thought, without sharing the genealogical framework related to it. And, as we tend to believe, the second alternative seems to be the most likely.

Despite a patent rarefaction of genealogical leitmotiv in Brazilian studies in History of Education based on Foucault, it is possible to conclude that there are several Foucaults at play in this set, which leads to a volatile gradient regarding the incorporation of their ideas into a research method. And, if such a point of view is correct, a background question would remain to answer: under what circumstances and under what conditions would it be possible to designate an investigative historical exercise - regardless of the disciplinary affiliation of its author - as a Foucauldian research? According to Artières (2016, p. 386):

To analyze the microdevice of power, to understand how, at the moment of a certain event, however small - a prison riot or the writing of an autobiographical memory - something unheard of emerges: a force that suddenly modifies the state of things. Trying to write the chronicle of these upheavals, these moments of subjectivation is perhaps effectively trying to inscribe a work in Foucault’s footsteps.

The analytical record to which Artières refers covers the genealogical gesture and its theoretical (the surreptitious event producing difference) and methodological (the historical narrative of the inflection points and its subjectivation effects) demands. Hence, before the more or less explicit adherence to certain consensual formulations among Foucault’s followers/commentators, it is more relevant the procedural vitality of the analytical effort that wishes to be attuned to the French thinker; in other words, his footprints, never his compass.

In short, it would be a matter of honoring Foucault not by forgetting him, but by subsuming him by one’s own action. Cannibalizing him, maybe.

texto em

texto em