Melior est enim sapientia cunctis pretiosissimis:et omne desiderabile ei non potest conparari.

Book of Proverbs, 8:11.2

As an introit

Perhaps one of the best ways of approaching the understanding of the meaning of things in any other temporality is to do it by means of how the words defined them in that distant thought of which, like the listeners with attentive ears, we want to identify any whisper that indicates to us which direction to follow, which path to choose to find the script for its magic decipherment. What to say then when one is trying to understand what was done with the joining of images and words in another time, in a world that seems foreign to us, where everything was perceived from other keys of thought, from very different connections from those that today we use? What, then, was understood as an emblem in the Portuguese-speaking world in the early 18th century?

Very well. Before discussing this universe of emblems and their relations with the Franciscans living in Portuguese America, it’s necessary first seek to know what was said about this form of representation at that time, how they were given meaning, as explained not only its essence, but also its uses and purposes for the culture of the baroque era. The Fr. Raphael Bluteau (1638-1734), of the Order of Regular Clerics, defined them in 1712, in his Vocabulario Portuguez e Latino, printed at the Jesuit College’s typographies in Coimbra:

EMBLEM, Emblèma. It is a Greek word, derived from the verb Emballo, which means two contrary things, namely, To put in, & To put out, & what the Greeks called Emblimata, were ornaments, or false parts, which they glued to the golden vessels, or silver, and when they wanted to, they took these things off. Budæus in anno Pr. & Caelli. Also by this word Emblemata, the ancients understood the foliage of the sculpture, the brushes of the arnezes, garlands, reliefs, & other works, &works, which were called Argumenta, Parerga, Anaglypta, Chrysendeta, dedalmata, & ornamenta exemptilia. Today, among Humanists, Emblem is a metaphorical term, because of the meaning of material ornaments, came to mean some moral document, which opened in prints, or painted in pictures, is put to ornament of speeches, galleries, Academies, triumphal arches, etc. The Emblem has, as the motto, or empresa, body, & soul, viz., visible figure, & intelligible letter, but in many things differs Emblem from Empresa. 1. The more perfect is the Empresa, or Motto, the simpler, & composed of fewer figures. But the Emblem admits various figures, historical or fabulous, natural, or artificial, true, or chimerical; nor excludes, like the Empresa, human bodies; but rather with erudite morality it sometimes represents a Ganymede, who ascends, a Dedalus, who flies, a Phaeton, who falls, etc. 2. The object of the Empresa (according to its primitive use) is Heroic, & Particular. The object of the Emblem, is a general document, concerning the institute of human life. 3. The Empresa, as subtle, ingenious, & stout, uses an ambiguous, laconic letter, which declares concealment, & covering declare, which means. On the contrary, the Emblem, as familiar, popular, plain, & sincere, is clear, & diffusely expose, what teaches. Finally can the empresa, & the emblem have the same body, or figure, but not the same soul, or letter, as the letter of the empresa is to be proper, & particular, & the letter of the emblem is to be general, & dogmatic ; & with this warning by changing the soul, & not the body, I mean by changing the letter without changing the figure, you can turn the empresa into an emblem, & the emblem, into an empresa. Emblema, atis. Neut. Cicero uses this word in the same sense in which the ancient Greeks & Latins used them. I don’t know how she introduced herself, & this word remained in the Latin language, cause Suetonius says that Tiberius had ordered to scratch and scrape it from a step from the Senate, because it was a word begged for a foreign language.3

The most interesting is that already in 1789, when reviewing the work of Fr. Bluteau for a new edition printed in Lisbon, Antonio de Moraes Silva would greatly reduce the entry, giving it a new and extremely succinct writing:

EMBLEM, s. m. figure, hieroglyphic, or symbol, which alludes to some morality, which is ordinarily declared by some letter, motto, or letter to the figure; empresa, motto, emblem contains general morality; the empresa, or currency, private.4

In almost 80 years, the importance given to the explanation of the term seems to have been so much reduced in the learned circles of Portuguese speech, since the dictionary of Bluteau was one of the most respected works in Portugal and its colonies throughout 18th century. However, we must to consider that if there was a change in the way of seeing the being-in-the-world in the profane space, failing to give the same relevance to a language that from the beginnings of the Modern Age had become a key of understanding widely used in literate circles in general - beginning with the publication in 1499 of the allegorical novel Hypnerotomachia Poliphili [Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream or The Dream of Poliphilus] by Francesco Colonna at the Venetian typographic workshops of Aldus Manutius5 and, a few decades later, with the appearance of the Emblematum Libellus [“Little Book of Emblems”] from Andrea Alciato6, printed in Augsburg in 1531 - the truth is that in the conventual and religious Catholic circles the central idea of Emblematic, as presented already crystallized in the 16th and 17th centuries, lent itself extremely well to its use in the construction of mental images associated with catechesis and to moral admonition.

This didactic quality of the emblems was soon perceived by the Ignatians, whom from the first decades of their missionary action had already added their use to the practices of formative instruction and also to the intellectual cultivation of their religious. This is, in fact, an aspect highlighted by Luís Gomes in the entry referring to the term “emblem” of his E-Dicionário de Termos Literários7. The Jesuit priests knew very well how to use the constituent elements of the emblems to structure their preaching, revealing to the faithful, from a seemingly simple image, each of the many and complex possible layers of meanings contained therein, as if their sermons were a magical revelation of the sacred word, not a well-orchestrated intellectual construction for the purpose of achieving the persuasive effect of catechesis. The Fr. Louis Richeome, S.J. (1544-1625), author of Tableaux sacrez des figures mystiques du très auguste sacrifice et sacrement de l’Eucharistie, published for the first time in Paris in 1601, affirmed that the images taught in a “profitable, vivid and delightful” manner the things of God, and he has detailed these advantages clearly when has enumerated the uses of the emblems in the propagation of the things of the Faith and in defense of the Eucharist:

[...] there is nothing more delightful, that leaves nothing more sweetly in the soul, than the painting, that does not deepen it more deeply in the memory; which no longer effectively motivates the will to advance, and energetically encourages it to love or hate the good or bad object which has been proposed to, that is, I do not see in what a most profitable, vivid and delightful way can be taught the virtues, the fruits and the delights of this divine and sacred food of the body of the Son of God [= the Eucharist], than with the above mentioned expositions and with the air of this triple painting: of the drawing, the word and the meaning.8

Thus it can be seen that the use of the emblems among the members of the Society of Jesus reached the point where several works were written by Ignatian priests with the explicit purpose of presenting themes of doctrine through the Emblematic. This was also the case of Lux Evangelica sub Velum Sacrorvm Emblematvm Recondita in Anni Dominicas Selecta Historia & Morali Doctrina Variè Advmbrata9, written by the Fr. Heinrich Engelgrave, S.J. (1610-1670), released for the first time in 1648 and can be considered as one of the best records of this use, even going so far as to appear profusely in the collection of libraries of several other orders, such as those of the observant Franciscans, with the explicit purpose of serving in the instruction of newly professed novices and young religious.

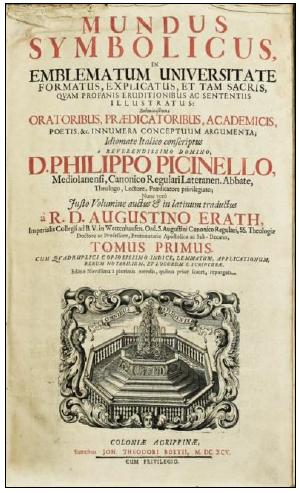

Only in the Paraíba’s Saint Anthony Convent Library, for example, appears in the inventory made in July 185210 - when the irremediable decay of the Saint Anthony of Brazil Province had already begun - that there were five copies of Emblematic books, divided between two copies of Fr. Engelgrave’s Lux Evangelica and three more of Mundus Symbolicus in Emblematum Universitate Formatus, explicatus, et tam Sacris, quàm profanis Eruditionibus ac Sententiis illustratus11, written by the Fr. Filippo Piccinelli (1604-c.1679), Augustinian canon, of which the first edition, in Italian, was published in 1635. Only this small detail of one of these conventual libraries already indicates how fruitful the approach to this subject in the world of seraphic instruction in colonial Brazil can be, although it has not yet received due attention in the researches of History of Books and Reading and of History of Education until today.

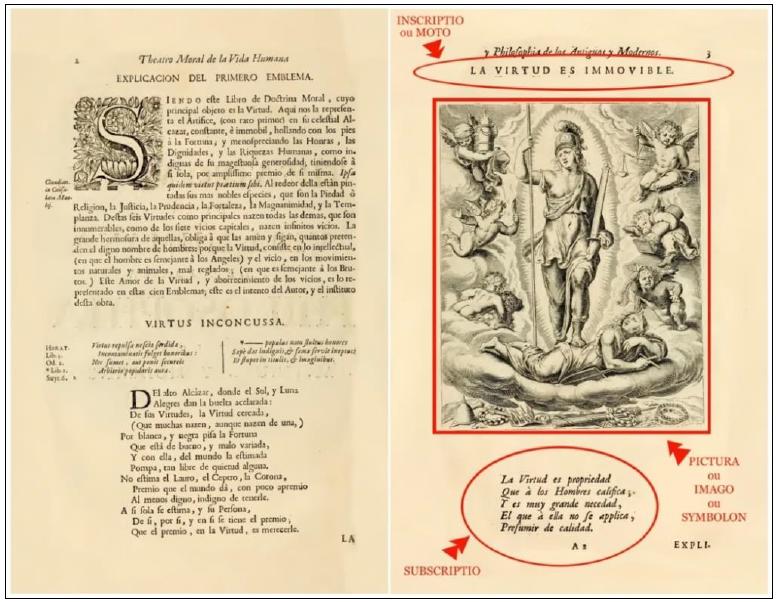

But there is one so important thing to consider when starting to think about this issue, having the Portuguese America as a scenario: in the 18th century the Republic of Letters was already striding towards the consolidation of the Lights ideals in Europe but, on the other side of the Atlantic, the apparent allegorical hermeticism of the emblems lends itself very well to the Baroque mental constructions, based on a dense symbolism engendered by daily oral traditions, deeply amalgamated by the rhythm of the sacred, thus constituting a vast vocabulary open to catechetical action of the religious orders installed arm in arm to the dominion of the Portuguese Crown. It is therefore necessary to detail the subject at hand. What are the constituent elements of an emblem? Ehrenfried Kluckert synthesized very well, in a panoramic article about the Baroque universe, the essential parts of this form of representation so widespread between the 15th and 18th centuries in the Western world:

An emblem is composed by the pictura or figure, the inscriptio or moto, and the subscriptio, epigram in Latin. The figure, also referred to as imago or symbolon, represents every imaginable motif of both daily life and the animal or plant kingdom. The moto, which appears at the top of the figure, refers to the theme of the emblem represented in the image. Finally, subscriptio clarifies and interprets what is represented on the emblem. Expressions that reflect wisdom of life or moral advice are often found in emblems.12

By adding the Emblematic to the proper uses of Christian religious practice, especially in the context of the Catholic Reformation and with regard to the setting of moral precepts and godly themes linked to the dogmas of the Faith or even the stories and accounts of the Old Testament or the Gospels, or still to philosophical and theological questions, adapting its presentation to the imagetic, poetic and symbolic discourse typical of this form of expression of the transition from Renaissance to Baroque, obviously adaptations were made by the authors of the works with this type of focus. Perhaps most striking is the introduction of a longer prose text explaining the pictura, often providing the elements to be used in a sermon or religious preaching. Obviously, many of the Emblematic books with this approach were written by religious, so it should be no wonder that such works circulated in the libraries of convent houses and seminaries of many orders, even if their authors belonged to a diverse congregation, some even with disputes between themselves - as was the case of the Portuguese observant Franciscans who installed the Custody / Province of Saint Anthony in Brazil and the Jesuits, involved in quarrels about the indigenous reductions in Paraíba and which resulted in the expulsion of the Ignatians from the Captaincy in 1593.

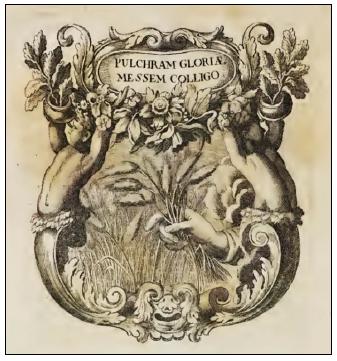

In the following figure you can see this adaptation in one of the many editions of Otto Van Veen’s Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana (1556-1629), originally published in 160713 under a different title, highlighting the link with the main inspiration of its emblems, the classical poetry of Horace. Of wide circulation throughout Europe between the 17th and 18th centuries, such work, although not authored by a religious, had wide acceptance in European Catholic circles, since Van Veen - who eventually signed with the Latinized form Vaenius - for a while during a period served D. Isabel Clara Eugenia, daughter of Philip II and governor of the Spanish possessions in the Netherlands in the early 17th century. The artist - who was also responsible for part of Peter Paul Rubens’ formation and had him as his own apprentice - was leaning against the innermost circle of post-Tridentine counter-reformist ideals14, as we can see.

Source: http://www.aechive.org/.

Fig. 1 “Virtus Inconcussa” or “La Virtud es Immovible”, first emblem of Theatro Moral de La Vida Humana, by Otto Van Veen, together with his explanation on the previous page, in an edition published in Antwerp in 1733 [p. 2-3], in the typography of Widow of Heinrich Verdussen. In particular the traditional elements of an emblem, respected by Van Veen, to which he added, before the verses of Horace in Latin, the explanation of the emblem in prose, which also presents the book and the objectives of the work, followed by verses in Castilian.

The Emblematic works in the collections of the Franciscan libraries of Portuguese America: the circulation of knowledge in the Baroque Atlantic world15

Unlike their European counterparts, which preserved their older books thanks to both the climate, a literacy culture and a more solid and complete conventual instructional structure, in Portuguese America the tropical airs did not benefit the Franciscan libraries of the colonial period. In fact, the humidity has facilitated the proliferation of micro-organisms, insects and fungi that irreparably damaged almost everything that was precious in these spaces in the second half of the 19th century, when the Province became extinct due to the prohibition, by the Brazilian Empire, of entry of novices in all religious orders16.

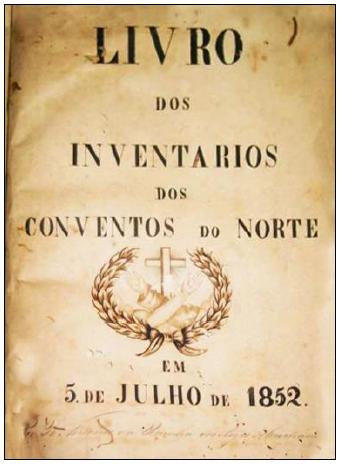

However, even though it is no longer possible to directly consult the holdings of these libraries as they appeared in the 18th century in their original locations, leafing through the pages of their printed works in folio, in quarto or in octavo, at least in relation to three of these places of reading, instruction and scholarship, we can still have a very close notion of the volumes that populated their baroque shelves, consulting the Livro dos Inventarios dos Conventos do Norte17, a document prepared in mid-1852 by the Friar Antônio da Rainha dos Anjos Machado, in order to subsidize a possible transfer of part of this collection to the Recife Faculty of Law´s Library18.

In addition, through a survey carried out by the Friar Hugo Fragoso in the 1990s19 it is also known that some volumes from the Salvador convent library are still kept in two cabinets in the current library of that religious house, but none of them are left from the collections of Igarassu or Paraíba. Possibly one or another volume listed as belonging to the Olinda’s convent in the Livro dos Inventarios may be either in the collection of the Pernambuco Public Library or else in the Recife Faculty of Law´s Library, today part of the Pernambuco Federal University. From the convent of Recife’s library, nothing was left, as reported by Pereira da Costa still in the end of the 19th century20. The library of the convent of Ipojuca, unfortunately, was ruined in the fire of 1939 that destroyed part of that religious house21.

Source: Photo by the author, 2015.

Fig. 2 Cover page of the Livro dos Inventarios dos Conventos do Norte, manuscript dated July 5, 1852, prepared by Friar Antônio da Rainha dos Anjos Machado, OFM. Collection of the Provincial Franciscan Archive of Recife.

The situation that presents itself as feasible to the research, therefore, is to start looking for the remains in the existing documentation and surveys, to try, even if minimally, to think about that universe of reading, readers and circulation of knowledge and world-views that engendered and was engendered by the symbolic relations that permeated the typical Baroque culture, crystallized in a very peculiar way in the works of Emblematics.

Thus, from the survey carried out by the Friar Fragoso already at the end of the 20th century on the collection of the library of the convent of Saint Francis of Bahia, in Salvador, and the list prepared by the Friar Machado in 1852, even though it is considered that the latter may contain inconsistencies and misunderstandings, given the number of items registered, it is possible to establish a panoramic view on the collections of the libraries of the convents of Our Lady of Snows of Olinda, Saint Anthony of Igarassu and Saint Anthony of Paraíba. However, if the annotation of the data on the works in both documents is not uniform, the records regarding the authorship or complete title of each book are often absent, as well as its date and, obviously, the place of its publication22 and this could hinder any inference about the collection, but even so, due to the accurate research work done by the Friar Marcos Antônio de Almeida, OFM - in his doctoral thesis defended at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, under the guidance of Serge Gruzinski - who managed to complete many of these gaps, I was able to tabulate the main themes of the works existing in the collection of these libraries at a period when the Province had already been in decline for almost a hundred years23, considering that the total volume of its volumes did not differ much from that existing in the seven hundred, especially with regard to the emblematic works, as their publication and consequent circulation fell in increasing disuse from the last quarter of the 18th century.

This is the panorama that can be seen in the following charts. Before dealing specifically with the Emblems books, I would like to make it clear that I will place them quantitatively in the collection of each one of the Franciscan conventual libraries.

The Saint Francis Convent of Bahia’s Library in Salvador

Starting with the present analysis by the library of the religious house of Salvador, founded in 158724, it’s necessary to highlight that it is known that at least since 1627 a custodial school, later provincial25, was used for the larger studies of the newly professed friars, and where they were to receive their training in Studia Artium (Logic), Studia Philosophiae (Philosophy) and Studia Theologiae (Theology).

Specifically in the case of the Bahia convent, the chart presented here is a result of the pioneering work of Friar Hugo Fragoso (1926-2016) in the 1990s, made from documentation and works still existing then in that house, and which were complemented by the Friar Marcos Antônio de Almeida in the research he developed in his doctorate at EHESS in Paris, treating on the work of Friar Antônio de Santa Maria Jaboatão and the Franciscans in Pernambuco in the 18th century26.

In a universe of almost 700 volumes raised by Friar Fragoso there was only one Emblematic title, with copies from two different editions, one from 1625 and the other from 1648, but its presence is also found in the convent, since several of his pictura were used as models when ordering 18th century tile panels to decorate the lower walls of its cloister, a space dedicated to meditation and prayer in the free hours of the Franciscan brothers. It is nothing less than Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana, by Otto Van Veen. Of the 103 emblems on their pages, the seraphic friars chose no less than 37 picturae to be commissioned by the atelier of Lisbon’s tile masters Bartolomeu Antunes de Jesus and Nicolau de Freitas27. They would have cost, according to the Friar Sebastião de Jesus Sant’Ana, convent’s guardian between 1802 and 1804, the large amount of 2:200$00028.

However, the formation of the library collection in the religious house of Salvador took place throughout the 18th century and appears at least in six moments noted in the Livro dos Guardiães of the convent during that period, which demonstrates the importance attributed to that space and the books for the friars who exercised the guardian function and also the need to highlight, in the official records of the convent, the large purchases that significantly increased the number of copies available to religious in formation and lectures. Amid the record of purchase of implements, repair works on roofs and enlargement of slave quarters, as it is common to appear in the Livro dos Guardiães, it’s so interesting to note even the details of some authors and the discrimination of the dimensions of the books - registering if they were printed in folio, in quarto or in octavo.

In 1743/1746 it was noted, for example, that “a collection of 18 volumes of Abulensis [was] put in the Library”29, while in the following three years the guardian ordered to buy “122 volumes of books on philosophy, theology, expositions, predicatives and historical “30. Two decades later, under the guardian of 1764/1768, “The work of Santo Anselmo was put into the Library, and several books that were damaged were repaired”31. Another huge acquisition was made in 1782/1783, when “65 volumes of new books by various authors were put into the Library, namely: in folio, 39; in quarto, 16; in octavo, 10. The following were put in more, with some use: in folio, 20; in quarto, 15”32. A few years later, in 1787/1790, “50 volumes of books were ordered from Lisbon”33. Finally, the last note that appears on the Salvador collection, already in 1790/1793, records: “At the Library, several volumes [have been purchased], already used. Four more in folio of Houdry were put in”34. Consider also that, as a rule, the Provincial Statutes current since 1708, in a specific chapter, determined, “so that the libraries provide themselves with books smoothly” that the guardians of all the convents provide, every year and a half, at least six volumes for the libraries of their homes, according to the needs of the masters of grammar and lecturers of philosophy and theology35.

As can be seen from Chart 1, the Emblematic works represent only 0.2% of the total number of copies from the 17th and 18th centuries remaining in the Salvador library and compiled by the Friar Fragoso already at the end of the 20th century. Almost 4/5 of the volumes available to the friars and novices were made up of works of theology (60%) and contents related to catechetical formation, such as sermons (19.6%), which should not be surprising, since the convent Salvador was home to one of the two centres responsible for higher studies of the novitiate in the Franciscan Province.

CHART 1: Themes in the Franciscan Library of Salvador - BA, data survey of Friar Hugo Fragoso - Decade of 1990 (books of the 17th and 18th centuries - 692 volumes)

| THEMES | NUMBER OF TITLES | % / TITLES RATIO | TOTAL VOLUMES | % / COLLECTION RATIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emblematic | 1 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Theology | 29 | 52.7 | 421 | 60 |

| Sermons | 3 | 5.4 | 136 | 19.6 |

| Ecclesiastical History | 3 | 5.4 | 39 | 5.6 |

| Franciscan History | 1 | 1.8 | 35 | 5 |

| Canon Law | 5 | 9 | 29 | 3.6 |

| Ecclesiastical & Papal Papers | 2 | 3.6 | 13 | 1.9 |

| Catholic Doctrine | 2 | 3.6 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Bibles | 2 | 3.6 | 4 | 0.6 |

| Religious Chronicle | 2 | 3.6 | 7 | 1 |

| Philosophy | 2 | 3.6 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Liturgy | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Pity | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Moral Doctrine | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.1 |

| TOTAL | 55 | 100% | 692 | 100% |

Source: FRAGOSO, 2006; ALMEIDA, 2012, vol. 2, p. 482 -491.

However, this apparent numerical discrepancy regarding the availability of Emblematic works in that collection should not be considered as a demerit. The fact that the emblems on the pages of Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana were transferred from the library environment to the walls of the lower cloister shows, in a very crystalline way, the importance given by the Franciscans to the allegorical language of the Emblematics as a way to religious meditation in the things of spirit, morals and Christian dogmas. All the decorative elements of the seraphic convents were done in this sense, always: directing the thought towards the things of the Faith, within the historical culture of Franciscanism and its interpretations about being-in-the-world. The tiles with the emblems located in an area of exclusive circulation for religious, in fact, also only reinforces their didactic role in the activities of the provincial school.

Source: http://www.archive.org/.

Fig. 3 Cover page of Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana, by Otto Van Veen, in folio edition published in Antwerp, 1733.

Friar Hugo Fragoso was also a historian of the Franciscan order in Brazil and a renowned expert in these set of tiles, and synthesized very well the meaning of its use in the conventual space in Salvador:

If all human life was a theater, convent life was also an expression of a specific theater too. Around the corridors of the cloister, a large part of this theater was unfolded. And here something similar to an osmosis would have occurred between the royal theater of the friars’ life and the theatrical representation on the tile panels. It is that the friars who ordered these tiles from Lisbon, quite possibly, made a Franciscan reading of the stoic philosophy of these panels. And the fact that, at the end of each of the four wings, there is, above the tile ashlar, the image of a saint. His fixation in this place also seems to have been a search for the Christianization of this entire mythological world.36

Taking the proportion of the presence of Emblematic works in the collection of the library of the Salvador’s convent as a parameter, it should not, therefore, be surprising that this level to be surpassed among the works of the other three libraries that have documentary records in the 19th century. In all of them there are few volumes available, although in Paraíba and Igarassu, if taken proportionally in relation to the total number of works, certainly the Emblem volumes reach greater prominence compared to the total number of works in both bookstores in the mid-19th century.

Source: Photo by the author, 2007.

Fig. 4 Tiles from the cloister of the Saint Francis of Bahia’s Convent, attributed to the workshop of Lisbon’s masters Bartolomeu Antunes de Jesus and Nicolau de Freitas, actives in the 1740s, based on the emblems of Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana, by Otto Van Veen. They were fixed on the walls between 1746 and 1748.

Source: http://www.archive.org/.

Fig. 5 “Virtus Inconcussa” or “La Virtud es Immovible”, first emblem of Theatro Moral de La Vida Humana, by Otto Van Veen, a pictura of his 1733 edition, published in folio in Antwerp.

Source: Photo by the author, 2007.

Fig. 6 “Virtus in concussa”, Bartolomeu Antunes de Jesus and Nicolau de Freitas (atrib.), c. 1740-1745. Church wing, inferior cloister of the Saint Francis of Bahia’s Convent, Salvador, Bahia.

Perhaps it is also interesting, therefore, to consider which books we are talking about, with regard to these other seraphic houses, and what their importance and scope in the cultural universe of the 18th century, both with regard to the Emblematic but, especially, in the field of post-Tridentine ideals and their relationship with Seraphic Pedagogy.

The Our Lady of Snows Convent’s library in Olinda village

The Our Lady of Snows convent, in Olinda, for example, was the other house in the Franciscan Province to which a part of the young friars went after they had made their first vows, and it was there that they should carry out their higher studies, and for two more years to deepen their training in the field of the three areas already started in lower studies, distributed in several disciplines such as Rhetoric, Greek and Hebrew - these three are mandatory in the initial formation of the novitiate - in addition to Philosophy, Ecclesiastical History, Dogmatic Theology, Moral Theology and Exegetical Theology37.

Our Lady of Snows was the first convent founded by the Franciscans in Brazil, in 158538, when the Custody was actually installed, still subordinated to Portuguese observers, and already in 1607, when the provincial Chapter was held in Lisbon, it was decided to create Arts and Theology course at that religious house, “because there is more comfort for that, nor can the arguments & exercises of the study be distracting, but rather to build up the novices in it”39.

Thus, it is important to consider that the Olinda Franciscans’ conventual library had a collection of considerable dimensions in the 18th century. Following the listing of the Livro dos Inventarios made by Friar Antônio da Rainha dos Anjos Machado, even for the item “Various Subjects” - very evasive in greater detail about the works, in fact - an incongruity is reached, since the 1852 document reports a total of 896 volumes, plus 30 volumes of Dogmatic Theology that would be outside the convent , on loan, at the home of a certain Dr. Farias40, however, when counting the total number of copies reported for each title, it amounts to more than 1,200 books in the library’s collection. Considering that the Report of Francisco Augusto Pereira da Costa prepared for the Government of the Province of Pernambuco in June 1886 pointed out the existence of 1,578 volumes in the library of the Franciscan convent of Recife, which were then completely useless to be relocated to the Provincial Public Library, reason for the elaboration of the document, I believe that the collection of the Olinda library was really around 1,200 copies in 185241.

As can be seen in Chart 2, which lists the themes of the volumes in the library of Olinda, Emblematic’s works in its collection represented no more than 0.7% of the total of books, with only three titles:

CHART 2: Themes in the Franciscan Library of Olinda - PE, (1852’s inventory - 896 [1.248?] volumes)42

| THEMES | NUMBER OF TITLES | TOTAL VOLUMES | % / COLLECTION RATIO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emblematic | 3 | 9 | 0.7 |

| Theology & Biblical Studies | 62 | 362 | 29 |

| Sermons | up to 100 [?] | 297 | 23.8 |

| Ecclesiastical History | 7 | 113 | 9 |

| Moral | 15 | 26 | 2.1 |

| Bible | 2 | 25 | 2 |

| Franciscan History | 5 | 22 | 1.8 |

| Ecclesiastical & Papal Papers | 10 | 20 | 1.6 |

| Philosophy | 8 | 17 | 1.4 |

| Canon Law | 3 | 10 | 0.8 |

| Dictionary | 4 | 14 | 1.1 |

| Mystic | 5 | 7 | 0.6 |

| Marian Studies | 4 | 7 | 0.6 |

| Hagiography | 4 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Doctrine | 3 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Prayers | 2 | 5 | 0.4 |

| Catechism | 3 | 4 | 0.3 |

| Oratory | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Liturgy | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Others | [?] | 293 | 23.4 |

| TOTAL | up to 400 [?] | 1,248 | 100% |

Source: Data organized from the consulted documentation and from ALMEIDA, 2012, vol. 1, p. 192; vol. 2, p. 492 -514.

Among such Emblematic works the one with the most copies, no less than five, is precisely the main one of Fr. Filippo Picinelli, the same Mundus symbolicus which also had three copies in the Franciscan library of Paraíba. The peculiarity of this book lies in the fact that it was conceived by its author as a compilation of emblems that accounted for all the possibilities of interpretations of the things created by God. In other words, Picinelli understood that the world could be read symbolically as the Book of Creation, in the same sense as that proposed in Romans 1:20: “Because His invisible things, since the creation of the world, both His eternal power and His divinity, are understood, and clearly seen by the things that are created, so that they are inexcusable”.

The Mundus Symbolicus was an extremely ambitious Picinelli’s project and had the explicit intention of, in Genoveffa Palumbo’s view, “to build a real symbolic universe that constituted a kind of parallel world, a cultural world, large and complex like the natural world, with its rules, its objects and its limits”43. Mario Praz, in his classic work on the Emblematic universe in Baroque Europe, written in the 1930s, considered Canon Picinelli’s book as a true encyclopaedia of emblems designed for the practical use of preachers in his sermons44, in other words, a adaptation of the Baroque symbolic and allegorical language - so typical of the emblems - to the post-Tridentine precepts of persuading by the senses, of using images, of catechizing for emotionality. Nothing less than a cutting-edge formation for the newly professed friars of the Saint Anthony of Brazil Province, therefore, making available in one of its largest conventual libraries such work of reference at the time.

Source: http://books.google.com.br/.

Fig. 7 Cover page of the first volume of Mundus Symbolicus in Emblematum Universitate Formatus, of Fr. Filippo Picinelli, in folio edition published in Cologne, 1695.

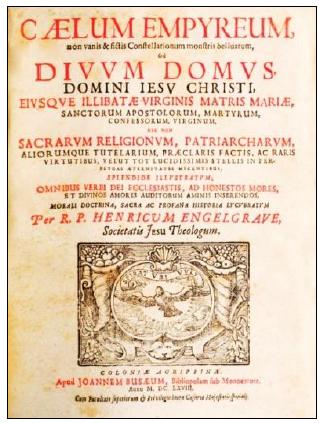

The second Emblematic title in the Franciscan library of Olinda is by Fr. Heinrich Engelgrave (1610-1670), S.J., a Flemish religious who served as rector of the Ignatian schools in Oudenaarde, Kassel and Bruges45. It is Cælum Empyreum46, also known as Cœleste Pantheon, which has three copies in this collection and is a compilation of sermons, organized from the liturgical calendar and with the motivation of the saint’s feasts, starting by Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. Together with Lux Evangelica, also by Fr. Engelgrave, it was a work of relative success in ecclesiastical circles in the mid-17th century and throughout the 18th - between 1657, the year of its launch, and 1727, that is, in seven decades, it had at least 66 editions in Latin or German47.

It is possible to attribute the usefulness of its circulation among the secular religious and belonging to different orders and congregations both to its format - since most of the editions were in quarto, i. e., of dimensions designed for a more daily handling - as to the fact the work also provides elements of catechetical oratory structured based on the logic of the emblematic: after a picture - or even an emblemata nuda48 in some editions, such as in the one of 1727 - an argumentvm followed with a text exposing some themes that were soon unfolded in some motti, in addition to elements articulated around the feasts of the saints, with details of the hagiography, excerpts from the scriptures, classic Latin verses, everything that could contribute to the persuasive result of the symbolic construct intended by Engelgrave. Image and persuasion, the basis of Baroque culture, therefore, appear disguised in post-Tridentine discourse, and serve as a substrate for the formation of novices and the improvement of the friars of the Franciscan house in Olinda.

Source: http://books.google.com.br/.

Fig. 8 Cover page of Cælum Empyreum, by Fr. Heinrich Engelgrave, in quarto edition published in Cologne, 1668.

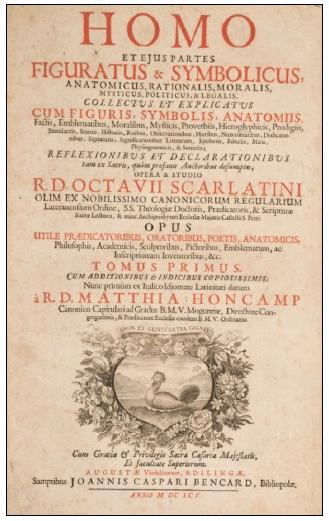

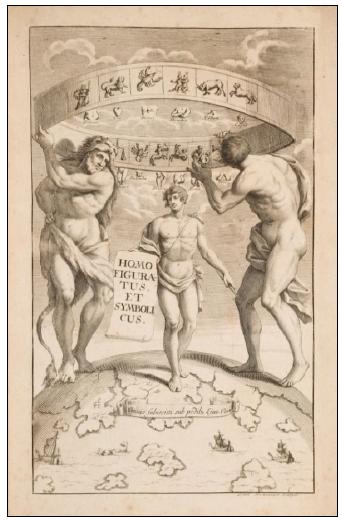

The third Emblematic work in the collection of the Olinda’s library had only one copy, but it is perhaps one of the most sophisticated and complex of all those that were part of the Franciscan bookshelves in the Saint Anthony of Brazil Province. I mean Homo et Ejus Partes Figuratus & Symbolicus49, by Fr. Ottavio Scarlattini (1623-1699), regular Lateran canon and mathematician50, whose first edition in Italian is from 1684. In the frontispiece illustration of his 1695 Latin edition, published by the workshops of Johann Caspar Bencard (1649-c.1720) in Augsburg and Dilingen, Germany, the typical Baroque allegorical language and also of Emblematic joins the post-tridentine ideals: in the beautiful engraving by Leonhard Heckenauer (1655-1704) the top of the globe brings the representation of the perfect man - who can be associated with the biblical Adam - flanked by two colossal beings that support a wide circular stripe with the Zodiac constellations, associated with parts of the human body. Under the feet of this Edenic Baroque being, a banner with a Latin verse from Psalm 8 taken from Vulgata: “Omnia subiecisti sub pedibus Ejus”, in other words, “Everything is subject to your feet”. Still the Renaissance idea of man as a measure of things, but shown through an Old Testament text, the attempt to join an incipient scientific perception of the world with the things of the Faith, nothing more Baroque than this apparent paradox.

Source: http://archive.org/.

Fig. 9 Cover page of the first volume of Homo et Ejus Partes Figuratus & Symbolicus, by Fr. Ottavio Scarlattini, in folio edition published in Augsburgo and Dilingen, by the workshops of Johann Caspar Bencard, 1695.

Source: http://archive.org/.

Fig. 10 Leonhard Heckenauer, “Homo Figuratus et Symbolicus”, 1695. Intaglio engraving, frontispiece illustration, first volume, Homo et Ejus Partes Figuratus & Symbolicus, by Fr. Ottavio Scarlattini, in folio edition published in Augsburgo and Dilingen, by the workshops of Johann Caspar Bencard, 1695.

It was precisely this 1695 edition of Homo et Ejus Partes Figuratus & Symbolicus that existed in the collection of the Franciscan library in Olinda51, a large volume in folio52 and, therefore, intended not for reading fruition, but for use as a reference work, in the library itself. Divided into two parts, usually the title was bound with both copies in a single book53. Briefly, it can be said that the work reconciled the symbolic universe of the Emblematic with the field of Moral Theology studies, the nascent medical-anatomical research and also with impregnations of the mystical beliefs inherited from medieval practices and early Modern Age. In the first volume, the individual organs of human body are studied, according to the conception of that time, focused primarily on the highlight of the senses, still under the strong influence of Galean medicine, always relating them to figurative emblems: eyes, lips, nose, heart, ears, etc. The second volume deals with general aspects of morals and human life, each one related to an emblemata nuda.

Source: http://archive.org/.

Fig. 11 Emblem “Revocare ad Malleum” [Bringing the Hammer back], Homo et Ejus Partes Figuratus & Symbolicus, 1695 edition, vol. 1, p. 140.

The Saint Anthony Convent’s library in Igarassu village

The other Franciscan library in Pernambuco that has a record of the contents of its collection is the one that existed at the Saint Anthony Convent of Igarassu, a house where the novices entered as postulants and carried out lower studies until the moment of professing their first vows. The books available in his library should, essentially, meet the needs of the Latin Grammar masters and the Theology and Philosophy lecturers who worked in the religious house. When analysing the thematic distribution of the works that still existed in the library in 1852 and which are listed in the Livro dos Inventarios elaborated by the Friar Machado, it is clear the focus on Theology and Biblical Studies, which represented almost 40% of the works available, as well as those dealing with Sermons, with 7%, as would be expected in an institution that housed the initial formation classes of novices, with studies divided between Studia Artium, Studia Philosophiae and Studia Theologiae, covering Rhetoric, Oratory, Greek, Hebrew, Latin Grammar, Theology and Philosophy.

CHART 3: Themes in the Franciscan Library of Igarassu - PE, (1852’s inventory - 143 volumes)

| THEMES | NUMBER OF TITLES | % / TITLES RATIO | TOTAL VOLUMES | % / COLLECTION RATIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emblematic | 2 | 4.08 | 4 | 2.8 |

| Theology & Biblical Studies | 20 | 40.81 | 54 | 37.8 |

| Liturgy | 4 | 8.16 | 4 | 2.8 |

| Franciscan Studies | 3 | 6.12 | 4 | 2.8 |

| Marian Studies | 3 | 6.12 | 4 | 2.8 |

| Sermons | 2 | 4.08 | 10 | 7.0 |

| Hagiography | 1 | 2.04 | 1 | 0.7 |

| History of Portugal | 1 | 2.04 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Ecclesiastical & Papal Papers | 1 | 2.04 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Others | 12 | 24.48 | 60 | 41.9 |

| TOTAL | 49 | 100% | 143 | 100% |

Source: Data organized from the consulted documentation and from ALMEIDA, 2012, vol. 2, p. 527 -533.

One of the two Emblem titles available in Igarassu was the Mundus Symbolicus by Fr. Picinelli, with two volumes in the collection, which demonstrates the importance attributed to this book by the Franciscans to the their novices formation, since it also appeared in the collection of Paraíba and Olinda, as I have already pointed out. The other book present in the Igarassu collection is very peculiar: it is the Livre curieux et utile pour les sçavans et artistes, by Nicolas Verrien (c.1660?-c.1730?), a very prominent master clerk and engraver specialized in monograms and emblems in the France of Louis XIV, who worked in Paris between 1685 and 1724. Of that Livre curieux two copies are known in that library.

Livre curieux came to light for the first time with royal privilege in 1685, receiving a reissue in the following decade, in 1694 or 1696, and a third edition already in 1724, in addition to a copy - which did not give credit to Verrien - published in Amsterdam in 1707, all of them printed in octavo54, i. e., it was a work of easy handling, designed for personal use. Its presence in a Franciscan house, where the religious formation of the postulants began, is quite significant, since this book was, above all, a small catalog of emblem models, or in other words, a type of reference and consultation handbook, but which also provided ideas for the creation of imagery allegories, whether visual or discursive. Within the scope of the Baroque persuasive culture, it was undoubtedly the most sophisticated manual in the field of Emblems to appear in a library, regardless of whether it was a religious or secular institution.

Source: http://archive.org/.

Fig. 13 Cover page of Livre curieux et utile pour les sçavans et artistes, by Nicolas Verrien, published in Paris with royal privilege, 1695.

Source: http://archive.org/.

Fig. 14 First page of emblems of Livre curieux et utile pour les sçavans et artistes, by Nicolas Verrien, with the respective explanation of the allegories on the next page, 1695.

Through the Livre curieux’s images the novices of Igarassu convent could learn to train their gaze to identify the symbolic analogies embedded in the emblems, and, in the same way, use them to construct new visual metaphors in their Oratory exercises. It is undoubtedly one of the most interesting ways for the establishment and naturalization of a so complex and erudite language like that of the Emblematic, no doubt, but it seems too, given the quality of the books of this type acquired by the Franciscans for their libraries, there was in fact a big concern to use them in their Pedagogy on a daily basis.

The Saint Anthony Convent’s library in the city of Paraíba

Finally, we reached the last collection registered in the Livro dos Inventarios by the Friar Machado in 1852, the one that belonged to the Saint Anthony Convent’s library in Paraíba. With a total of 78 titles and 184 volumes, the dimensions of the Paraíba’s collection did not differ much from that existing in the Igarassu library, although it exceeded it in more than 40 volumes and 30 titles, which may be explained by the distance in relation to the most dramatic theatre of the armed conflicts of Pernambuco’s Restoration, in the middle of the 17th century, and the fact that the friars abandoned the Paraíba’s convent during the Dutch occupation and kept the library’s collection in a safe place, avoiding the loss of works from the previous period to the presence of the invaders, a detail that may not have happened in Igarassu and it certainly did not happen in Ipojuca, as will be seen later.

CHART 4: Themes in the Franciscan Library of Paraíba - PB, (1852’s inventory - 184 volumes)

| THEMES | NUMBER OF TITLES | % / TITLES RATIO | TOTAL VOLUMES | % / COLLECTION RATIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emblematic | 2 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 |

| Theology & Biblical Studies | 35 | 44.9 | 74 | 40.2 |

| Canon Law | 8 | 10.3 | 16 | 8.7 |

| Bible | 1 | 1.3 | 13 | 7.1 |

| Marian Studies | 4 | 5.2 | 12 | 6.5 |

| Ecclesiastical & Papal Papers | 2 | 2.6 | 11 | 6.0 |

| Philosophy | 3 | 3.8 | 8 | 4.3 |

| Liturgy | 8 | 10.3 | 8 | 4.3 |

| Sermons | 2 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 |

| Christian Doctrine | 2 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 |

| Franciscan Studies | 2 | 2.6 | 3 | 1.6 |

| Dictionary | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Ecclesiastical History | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Others | 7 | 9.0 | 21 | 11.4 |

| TOTAL | 78 | 100% | 184 | 100% |

Source: data organized from the consulted documentation and from ALMEIDA, 2012, vol. 2, p. 515 -526.

Perhaps the determining factor for this difference is that already in the first years of the Custody a Latin Grammar class was installed in that religious house, destined to the postulants and also to the children of the colonists, and thus, despite not usually teaching minor studies in Theology or Philosophy, in the Provincial Statutes of 1709 - which in several aspects repeated the determinations of the 1683 counterpart document - the functioning of a permanent Magister Grammaticæ in the Paraiba house had been established:

So that the Students, who are going to go to Philosophy, are good Grammarians, we order that in the Convent of our Father Saint Francis of the City of Paraíba there should be a study of Grammar, because it is the foundation of all the most sciences; for which the Brother Minister will elect when visiting ten, or twelve Religious, who come to have genius, & ability for the most sciences; & for the Master of said Grammar study, he will choose the Religious from the whole Province, who is best seen in it, so that his explanation can be used by the disciples; to which Master we exempt from all the Choir & obligations of the Convent.55

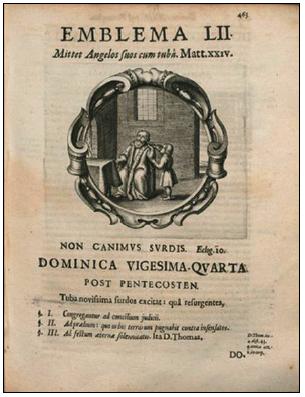

Given the responsibility of teaching Latin grammar to postulants, therefore, the quality of the library’s collection in Paraíba must also be considered. It contains two copies of Suplemento ao Vocabulario Portuguez e Latino by Fr. Raphael Bluteau, what would be expected in a house where instruction to novices had this characteristic, of formation in the Latin language. As in the other Franciscan libraries, the books of Theology and biblical studies stand out in the Paraíba collection, with more than 40% of the titles and volumes of their shelves. The Emblematic books was only 2.7% of the collection, with five volumes and two titles: one of them was, as I mentioned, Mundus Symbolicus, by Fr. Piccinelli, with three copies; the other two volumes were of a title that had no less than 115 editions between 1648 and 175056, Lux Evangelica sub Velum Sacrorum Emblematum Recondita in Anni Dominicas, by Fr. Heinrich Engelgrave, S.J.

Source: http://www.flandrica.be/.

Fig. 15 Cover page of Lux Evangelica Sub Velum Sacrorum Emblematum Recondita in anni Dominicas, by Fr. Heinrich Engelgrave, S.J., published in Antwerp, in the workshops of the widow and heirs of Jan Cnobbaert, 1648.

Source: http://www.flandrica.be/.

Fig. 16 Emblem LII “Non Canimus Surdis” [Let’s not Sing for the Deaf], concerning the 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time, after Pentecost, Lux Evangelica Sub Velum Sacrorum Emblematum Recondita in anni Dominicas, 1648 edition, vol. 1, p. 463.

Lux Evangelica had editions in several prominent European typographical centres of the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Amsterdam, Antwerp and Cologne, appearing in different configurations, in in quarto or in octavo format, but always divided into two volumes. The first of them contains 52 sermons distributed on Sundays, preceded by an overview essay. The emblems that precede each of the sermons are reproduced in several editions as an emblemata nuda, i.e., without the pictura. In the illustrated editions, each pictura is attached to two motti: the first is a biblical text; the second is an excerpt from classical literature, usually Latin. Right after that, comes the indication of the feast or theme of that particular Sunday, then a small extract of the treaty is presented which will be developed later in the text. The description of the pictura follows, and in this excerpt the connection between the emblem and the sermon, between allegory and Christian oratory, between a whole universe of symbols and Baroque persuasion is skilfully constructed.

It was on this amalgamation between pictura and motti and his argument that Fr. Engelgrave deftly constructed an entire speech explaining the sacred texts that served as an inspiration for priests to prepare themselves for the exercise of preaching in their daily functions in the various masses they conducted. Lux Evangelica’s proposal was based on the model already consolidated at that time, of training the Jesuits with the use of Emblems as preparation for the art of homiletics57: in a Catholic world in which literacy was still low - contrary to what was conforming in the spaces expansion of Protestantism - oratory was essential for the transmission of religious ideas and the spread of the Catholic Faith. In this sense, the fact that Engelgrave served as rector of three Jesuit schools in the south of the Netherlands certainly prepared him very well to adapt his work to the formative intentions of the Society of Jesus and the Ratio Studiorum, which other Catholic congregations and religious orders adapted to the use his Emblematic book in theirs seminarians, postulants and novices instruction. The emblems of the first edition, published in Antwerp, were designed by Hendrik Snyders, an engraver who was active there in the middle of the 17th century, and were reproduced in the following editions, even when there was some change in the number of pages or the presentation of the text of one to two columns. The second volume of the work follows the same scheme as the first in the illustrated editions, but is dedicated especially to the feasts of the liturgical year and to the Church’s saints and the Virgin Mary58.

Possible inferences: as a way of a conclusion?

Trying to reconstitute the collection and scale the reach of libraries in the Franciscan Province of Saint Anthony of Brazil are obviously challenges that can never be fully achieved, for various reasons, starting with the tragedy that represented the inexorable destruction of so many irreplaceable works that all shelves in the thirteen convents of the Province kept in the 18th century, since even houses where lower or higher studies or fixed classes of Latin grammar did not develop daily should, by virtue of the Provincial Statutes, have a space to store books and serve for the friar´s study hours59. If only with the thematic description of the collection of libraries in four of those convents and focusing on their Emblematic books, it is already possible to make some very significant inferences about such reading spaces, their relationship with Seraphic Pedagogy and, even more, the importance of these specific books for the basic instruction and friars’ theological and philosophical refinement, since the novitiate and even after they have already professed their vows, what to think if perhaps we knew what books existed in the libraries of other Franciscan religious houses?

Libraries and the world of books constituted an indispensable universe for the foundation of the Franciscan praxis in the secular world, this has already been discussed by several authors with regard to the European scenario60 and, clearly, it is shown as a characteristic also present among the seraphic observers who settled in Portuguese America. From the thick volumes of Theology, Biblical Studies, Philosophy, Marian and Franciscan Studies, Hagiography, Liturgy, Christian Doctrine and Oratory came the theoretical bases for catechetical action, while the Emblematic works undoubtedly came refinement and scholarship to enable the friars to build images full of persuasion, whether they were in fact crystallized in works of stonework or wood carving, or else in nimble brushwork on altarpieces, medallions, panels and ceilings scattered throughout the province’s convents - since even though the friars did not directly execute these pieces, they commissioned them and established their execution plans - or in sermons that were pearls of baroque oratory and of which very few records remain to nowadays.

In chart 5 it is possible to observe the distribution of Emblematic works by the libraries that I analyzed in a panoramic way and it’s clear that, even in convents of lesser projection, such as the ones of Igarassu and Paraíba, such works were present, and if in houses Olinda and Salvador, where the major studies of the young professed friars took place, and more clearly in Pernambuco, there is a certain record of the existence of a greater variety of these titles, obviously the Franciscans attributed some importance to this theme for formation and scholarship of their friars. The fact that the emblems of the Theatro Moral were chosen to decorate the tiles in the cloister of the Salvador’s convent only reinforces this understanding.

CHART 5: Emblem books in the Franciscan Libraries Saint Anthony of Brazil Province - BA / PE / PB - 18th century

| BOOKS | SALVADOR CONVENT | OLINDA CONVENT | IGARASSU CONVENT | PARAÍBA CONVENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theatro Moral de la Vida Humana | 2 | - | - | - |

| Mundus Symbolicus | - | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Homo et Ejus Partes | - | 1 | - | - |

| Caelum Empyreum | - | 3 | - | - |

| Lux Evangelica | - | - | - | 2 |

| Livre Curieux | - | - | 2 | - |

| TOTAL VOLUMES | 2 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

Source: data organized from the consulted documentation and from ALMEIDA, 2012, vol. 2, p. 482 -533.

In the Our Lady of the Snows Convent’s library there were also at least two volumes of a very interesting book, which was not of Emblematics, but which summarizes the sense of books and libraries in the seraphic universe in its frontispiece illustration. This is the Bibliotheca Universa Franciscana, by Friar Juan de San Antonio (OFM), also known as Juan de Soto (1667-1736)61.

Soto’ book intended to cover the biography, even if only briefly, of all Franciscan authors born until the date of its publication in Madrid, i. e., 1732 for the first two volumes, and 1733 for the third. Presented in large format, in folio, it was a reference book, designed for handling and occasional consultation, and its natural environment of use was the libraries, without a doubt. But looking to the engraving on the frontispiece of his first tome, there we can see the idealization of the desirable library in the seraphic world: the winged patriarch of the order, with the same wings as the seraph who printed his stigmas, rests on a stylized terrestrial globe, and this in turn is presented surrounded by subjects of interest to Franciscan authors, practically an inventory of the themes present on the shelves of the conventual libraries: “Res Biblicæ, Expositiva, Dogmatica, Escholastica, Mystica, Ascetica, Moralia, Concionatoria, Cathechistica, Regularia, Philosopiica, Christifera, Mariana, Juridica, Politica, Mathematica, Historia, Medica, Astrologia, Pœtica, Grammatica, Varia”. Involving the globe, an exhortation to pay attention to laws and scriptures, with a final reference to an excerpt from the vulgata, the second chapter of the Second Book of the Maccabees, where the care of books and their conservation is admonished. In addition, the entire globe appears populated by eyes and pens of writing, possibly in an allegorical representation of the Franciscan look and writing scattered around the orb.

Leaving San Francisco’s lips, as was common in Baroque representations, tapes represent his speech, containing a variant of another part of the vulgata, Psalm 18, beginning with his 5th verse: “In omnem terram exivit”, i. e., “It was preached all over the Earth”. To the excerpt from Psalm 18, references to Regula Bulata and to the mission and catechesis practiced by the poverello d’Assisi are added.

Source: http://bdh.bne.es/.

Fig. 17 Friar Matías de Irala Yuso, “Funiculus Triplex Dificile Rumpitur” [It is Difficult to Break the Cord of Three Knots], image from the frontispiece of Bibliotheca Universa Franciscana, by Friar Juan de Soto, vol. 1, Madrid, 1732. Intaglio engraving; 29,2 X 18,7 cm.

The four Franciscan libraries presented here briefly, and even more, the chosen approach, of entering its universe of study and scholarship through a set of books that were typical of the Baroque culture, i. e., the Emblematic books and their symbolic and almost always hermetic language, which referred to deciphering keys often related to elements of classical culture external to the Catholic universe, demonstrate, in my understanding, how sophisticated the Seraphic Pedagogy practiced in Portuguese America could be, even without the so famous Franciscan Studia Generalia62 wich existed in conjunction with European universities.

It was certainly through the books present in the collections of these libraries, and not just those of Emblematics, that knowledge circulated between overseas and the colonies, even if there was an explicit prohibition, in the Statutes of 1709, to borrow or withdraw works from one convent to another within the Province63. Perhaps the determination arose precisely because of the daily traffic of books between religious houses without proper control and registration, which must have caused the loss of some volumes, because in the middle of the 17th century there is reference not only to the size of the library of the convent of Ipojuca, but also to the circulation of books between that religious center and the Paraíba convent:

190 books were found in this library, I mean 200 books with the little ones. Among which the ordinary glosses come in six volumes, the parts of sacred theology in five volumes, the works of Saint Augustine in five volumes, the works of Saint Bernard in two, the Incognito, the works of Moral of Diana in two large volumes. These books include this library of the convent of Saint Anthony of Ipojuca. Eleven books are here from the house of Paraíba; the rest of the books in this convent, as some in the other houses, were lost among the successes of the war. And actually, I sign myself today on the April 24th, 1648. (Signed) Friar Jácome da Purificação, visiting commissioner. Friar Masseu de S. Francisco, secretary. 64

Considering that in the middle of the 17th century, the library of the Ipojuca convent had two hundred volumes already after the West India Company invasion and the battles of the Pernambuco Restoration that culminated in the Dutch expulsion, it’s feasible to suppose that in the 18th century its collection was larger, considering the norms of constant provision and care with the books that the guardians of the seraphic houses had to follow since the Custody period, as was usual among the Franciscans. As it is unfortunately no longer possible to know what the contents of the Ipojuca shelves were, we can at least imagine the richness of what was hopelessly lost, from this brief account of the visiting friar, dated from the mid-seventeenth century. There was probably also a title in that religious house whose pages were adorned with emblems.

This is because I believe that Emblematics books, in my understanding, were largely responsible for the crystallization of allegorical scholarship present in the Baroque decoration of all convents in the Province of Saint Anthony of Brazil. When choosing themes and forms to represent them, define which attributes and symbolic elements to add to sacred images or even simple decorative elements, referring to the emblematic works of their libraries, sometimes more explicitly, sometimes more veiled, the friars were transposing to visuality a conception of being-in-the-world that was understood as deeply amalgamated with the sacred, a way of putting itself into daily life that was extremely baroque and, for this very reason, very current in the 18th century.

It is in the Emblematic works that this symbolism is easily found, and the convents of the Saint Anthony of Brazil Province had not only a significant collection of them, considering the reality of libraries in the 18th century both in the Americas and even in Europe, but also they had the most prestigious titles, even if they were few in variety - only six titles. They were what today we now call best sellers, like Lux Evangelica by Fr. Engelgrave, with its more than 115 editions, for example. After all, it seems that America, at least in this matter, was not placed as far on the periphery of the Empire as was once thought...

texto en

texto en