Initial considerations

Playing ball, practicing exercises, singing, and even playing games may be a memory of many students about Physical Education classes in the first grades of primary school. In this sense, this study aims at analyzing memories of teachers of a school in Caxias do Sul/RS about how they organized Physical Education classes, from 1974 to 1985.

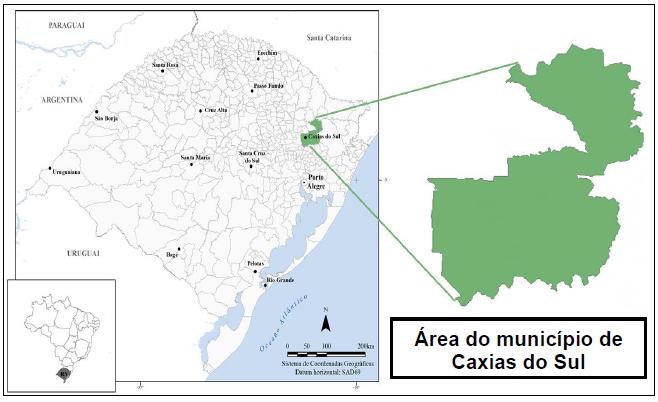

The municipality of Caxias do Sul is located in the northeastern region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul (RS), as shown in Figure 1. Currently the municipality has a total area of 1,638.34 km², with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, located about 127 km from the capital Porto Alegre. It borders to the north with São Marcos, Campestre da Serra and Monte Alegre dos Campos; to the south with Vale Real, Nova Petrópolis, Gramado and Canela; to the east with São Francisco de Paula; and to the west Flores da Cunha and Farroupilha (CAXIAS DO SUL, 2017).

Source: RIO GRANDE DO SUL (2019). Adapted from Rio Grande do Sul State Geopolitical Division, State Foundation for Economics and Statistics.

Figure 1: Caxias do Sul highlighted on the map of the Rio Grande do Sul state

The processes of implementation of Giuseppe Garibaldi School (GGS)2started in the beginning of 1974, at a meeting held at the residence of Mr. João Neves, between Cristo Redentor Neighborhood Association3 and the Mayor Mario Bernardino Ramos. At this meeting the community's demands were presented, highlighting the claims for building a school. The mayor appointed the secretary of education, Santina Barp Amorim, to be responsible for resolving the legal procedures and organization for the opening and functioning of the school (EMEFGG, 1974).

To expedite all bureaucratic processes, given the urgency exposed by the community, the local government suggested renting the lower floor of the residence of Mr. João Neves. However, the space would need some physical adaptations to receive students. This was made possible by the aid of Mr. Ernesto Romualdo Rissi, president of the Residents' Association, and some members of the community, who carried out the work (EMEFGG, 1974; JACIRA, 2017).

For Luchese (2014, p. 147), although a research might have a local character investigating the educational processes related to primary Physical Education4 performed in a specific institution, many of these processes are connected “[...] by networks of contexts and relationships at different spatial levels: local, regional, national and international ”, either through relationships, practices and/or human cultures.

The research was based on two primary teachers from different periods and educational backgrounds. The first teacher, Jacira Koff Saraiva, graduated from the primary teacher training course in the late 1960s, was one of the promoters for the founding of the school in 1974, as well as accumulated the duties of principal and teacher that same year. The second teacher, Jaqueline Gedoz Vita, graduated from the primary teacher training school in the early 1980s, joining the school in 1982 to teach primary school. It is noteworthy that both teachers received a generalist training regarding Physical Education (JACIRA, 2017; JAQUELINE, 2017).

The time frame adopted begins in 1974 with the constitution of GGS (Giuseppe Garibaldi School), and ends in 1985 with the indirect election of President Tancredo Neves, on January 15, 1985 (MENDONÇA, 2005). This period of the Brazilian military civil regime was characterized by the practice of Physical Education in schools, mainly through sport and civic activities, as a formative plan focused on the ideal of a grand nation, in industrial, social and economic development, as well as on control and social alienation of subjects and diciplined bodies. According to Oliveira (2002), school Physical Education, conducted by Law No. 5.692/715 in its 7th article, became compulsory at all school levels. This requirement was regulated by Decree No. 69.450/71, which set standards for Physical Education classes within the school environment.

Thus, Physical Education in the school was structured according to the formative current of sports, which in many moments was related to technical teaching and still emphasized skills related to civic activities. This overview aimed at the formation of a disciplined subject with good skills for the labor market. Thus, we seek to compare the national movement that occurred with Physical Education in primary education with the local scope, highlighting the generalist formation of primary teachers, the physical spaces adapted for classes and the scarcity of didactic materials to organize other educational possibilities.

Theoretical and methodological perspectives

Historical narratives become plausible and credible from theoretical choices and lenses that help researchers elucidate their goals. Thus, the selected theoretical assumptions are supported by Cultural History, by the narrative possibilities of different life courses, institutions, social groups in different forms and concepts.

For Souza (2011), Cultural History allows researchers to analyze schooling processes, daily experiences and the contexts of their constitutions in given places and moments. We also justify this theoretical choice by “[...] identifying how in different places and moments a particular social reality is constructed, thought, given to be read” (CHARTIER, 1988, p. 16-17). A relevant contribution of Cultural History was constituted by the new possibilities in the use of sources, such as photographs, ordinary documents6, notebooks, diaries, as well as orality and the use of memories as documents (BURKE, 2008).

From the above, we sought to highlight the forms of organization and development of classes and practices of primary physical education led by teachers Jacira and Jaqueline, permeating the narrative between the historical context of the period and the memories about school daily life. For Halbwachs (2006), memories are intertwined with social coexistence, and their “constructions” occur through the relationships between the subjects or groups of which they are part, and which may be the result of the influences to which they are subjected, as, for example, family, school, society, government, power relations and their own rules. From this point of view, memories are attested both individually and collectively.

Moreover, according to Hobsbawm (1998), memories are constituted through an individual selection of the infinite memories that are remembered or that can possibly be remembered, and which can provide encounters of a past with the present, structured by the “[...] experiences, spaces and places, moments, people, feelings, perceptions/sensations, objects, sounds and silences, scents and flavors, textures, forms” (STEPHANOU; BASTOS, 2011, p. 420). The recollections of the subjects can highlight elements, evidence, subsidies that other documents do not reach, helping researchers to understand the ways in which primary teachers organized Physical Education classes and, above all, the representations of school practices of those places and moments.

School practices, according to Vidal and Schwartz (2010), are engendered by the creative and active actions of the subjects that influence the ways they understand their identities, experiences and perceptions of the world. They are produced in the school environment, in the relations between the subjects in different stages of development, composed by rules, relations, values, social and cultural principles, as well as in the direct and indirect relations of the social groups that take part in the process, because these are “[...] the practices that aim at recognizing a social identity, exhibiting their own way of being in the world” (CHARTIER, 1988, p. 23).

From a methodological point of view, Oral History was selected for the perspectives of producing a historical “version and vision”, through the subjects' narratives about the practices, cultures, conjunctures, daily life and their relations (LOZANO, 2005). In this way, we chose to conduct semi-structured interviews, which after transcribed, organized and categorized became empirical documents subject to analysis, interpretation and contextualization. According to Ferreira and Amado (2005), Oral History is a scientific method that organizes and establishes criteria and procedures in the various ways of working on interviews. Memory is the essential subsidy for the use of this methodology, since

in oral history, the historian's object of study is retrieved and recreated through the memory of the informants; The instance of memory necessarily starts to guide historical reflections, leading to important theoretical and methodological developments [...] (FERREIRA; AMADO, 2005, p. 15).

Oral History values the memories of the interviewed subjects, which are relevant to those who experienced the events that are currently the object of research. In the context experienced by the interviewees, the assumptions of memory dimensions were also adopted, in this case the “conditioned forgetfulness”. As Grazziotin (2008, p. 62) makes clear, the fact of forgettingf memories can be perceived in societies,

[...] subjected to totalitarian regimes [...] that did everything to cause the forced amnesia of a society led to forget what is not desired at a given time, implanting another memory, conditioned to an intentionally created truth regime.

From this principle, teachers should theoretically be careful about the contents, knowledge and ideals that they organized and developed in the schooling processes. It is noteworthy that, although we adopt this assumption of memory dimension - the “conditioned forgetfulness" -, the interviewees did not show or mention any type of repression or censorship by the government, and reported having “freedom” to organize and develop their classes.

In reference to the 7interviews, ten guiding questions were elaborated but whenever new questions arose new questions were asked, constituting a semi-structured interview format. For Manzini (2012, p. 156), the semi-structured interview “[...] is characterized by a script with open questions and is indicated to study a phenomenon within a specific population [...]”. The selection of teachers aimed to bring together “[...] those who participated, lived, witnessed or became aware of occurrences or situations related to the theme and that can provide significant testimonials” (ALBERTI, 2013, p. 40).

The first interviewee8, teacher Jacira Koff Saraiva remembered the school foundation, the first physical spaces, the organization and the development of the classes. Jaqueline Gedoz Vita, the second interviewee, joined the new school facilities, which were inaugurated in 1976, in 1982 allowing her to understand how the physical improvements, the expansion of materials and the changes in the organization and development of the classes took place. Thus, it was possible to obtain evidence about both Giuseppe Garibaldi School places and moments and the differences in the organization and development of these classes.

Thus, the article was organized into five parts, in addition to the introduction. The first part presents the theoretical and methodological assumptions adopted for this study. In a second moment it contextualizes the period of the military civil regime and the educational processes related to classes and Physical Education practices at national and local levels. After that, the context is structured through the memories, which allowed us to reconstruct one of the possible stories about Giuseppe Garibaldi School classes and Physical Education practices, as well as the final considerations.

National and local context: ways to organize physical education in primary education

In this section, we present the educational context experienced at the national and local levels and their relationship with the ways of organizing and developing physical education classes in primary education. Research that focuses on particular school institutions is relevant to the field of the history of Brazilian education, as these institutions are part of broader school systems and are permeated by the values of each historical period (BUFFA, 2002).

The educational institutions of this historical period consisted largely of the so-called school groups. According to Bencostta (2005), this model of school institution differed from the others9 by creating the sequencing of primary education in four years, in which each grade has its own teacher, with the ordering of school knowledge contained in the teaching programs. It was in the school groups that new ways of teaching organization emerged, characterized by:

[...] rationalization and standardization of teaching, the partitioning of teaching work, the classification of students, the establishment of exams, the need for own buildings with the consequent constitution of the school as a place, the establishment of large and encyclopedic programs, the professionalization of teaching, new teaching procedures, a new school culture (SOUZA, 1998, p. 49-50).

Brazilian primary education, during the military civil regime, was based on technical teaching methodologies directed to training for the labor market. The technicist objective was aimed at boosting the economy of the country, through the qualification of the workforce, without pretensions of critical formation of the subjects. The government aimed at achieving its objectives of industrialization, labor qualification and economic growth also mediated by educational legislation reforms (FURLAN, 2013).

In this sense, the deprived educational formation had as its main objective the preparation for the labor market, “[...] and not for the development of broader and more diversified individual skills, thus forming a large mass manipulated by political and economic orders” (FURLAN, 2013, p. 2). These moral values, social and educational norms were implemented in the 1960s and endured during the regime by utilizing the “[...] repression and political ideological control of education, with the aim of eliminating any and all forms of criticism to consolidate its project of domination” (MACIEL et al., 2016, p. 6).

In the municipality of Caxias do Sul, school groups also constituted a large portion of educational institutions, especially between the 1970s and mid-1980s, when new ways of organizing teaching began to emerge. Primary education was based on three bases: reading, writing and arithmetic (DALLA VECCHIA; HERÉDIA; RAMOS, 2008). These local institutions also had the same characteristics as other Brazilian schools, but they had singularities, such as the feeling of belonging to an “Italian culture”, through the religiosity expressed by Catholicism and by school attendance linked to the discipline for the formation of a responsible citizen (DALLA VECCHIA; HERÉDIA; RAMOS, 1998).

Regarding Catholicism, Jacira and Jaqueline (2017) pointed out in their narratives that at Giuseppe Garibaldi School classrooms there was commonly a crucifix fixed on the blackboard, and that there were moments at the beginning of classes in which prayers were held. They also point out that class attendance was related to school duties and assessment activities. According to Iwaya (2000), some rites were characteristic and remained over the years in Brazilian primary institutions, especially the formation of queues before entering the classrooms and the control over the schedules for each activity, elements that make up parts of a culture of these primary institutions.

Regarding physical education at the national level during the 1970s, we can conjecture that the guidelines of the government, based on social and economic development, through technical education were fulfilled. This way, the performing of

[...] the technification of body practices would represent an improvement in the conditions of the workforce, in order to make it more efficient and effective in the production process; rationality and the planning of the economics of education then configured public policies and, consequently, school practices, leaving little or no space for the intervention of those subjects in history (OLIVEIRA, 2001, p. 36).

The interference of the national government on educational guidelines has made school physical education practically restricted to sports practices. According to Oliveira (2002), this interference may have been influenced by two factors. Sport was presented as a standardized and institutionalized practice that would be able to reproduce the pretensions of control, and that would not open educational possibilities for both teachers and students. The second point, according to the author, stems from the affirmation of sport as a mass cultural phenomenon worldwide.

The use of sports in the organization and development of Physical Education classes during this period was termed as a competitive current of teaching, by advocating technique and performance. School practices in Physical Education classes had as their main foundation the teaching and development of technique, gesture and sports repetition, reducing the possibilities of body practices to a few techniques reproduced in mechanized ways (OLIVEIRA, 2001).

For Soares et al. (2009), the competitive current in schools also contributed to restrict practices essentially to sports. Gymnastics10, athletics11 among other activities, were put in the background, which characterized the classes as sports training practices with a view to performance. Also, according to the authors, the social relations of Physical Education classes were directly impacted by the use of sports, which provided the constitution of a dichotomy evidenced by the “technical teacher” and “student-athlete”.

At the municipal level, during the 1970s, classes were organized and developed mainly by games linked to leisure practices. Sports, soccer and volleyball, maintained their prominent place in the classes, but they were performed in an adapted manner, as the school groups in the region did not have adequate physical spaces and there were few didactic materials (GIACOMONI, 2018).

Beginning in the 1980s, new movements emerged contrary to the technicist conceptions of education, as the military civil regime ended with the indirect election of President Tancredo Neves on January 15, 1985. Gradually, Brazilians are beginning to have a wider social, political and educational overview of the country (MENDONÇA, 2005). That widening of sight was aimed at “[...] the transition from a dictatorial political model to a redemocratization model” (SILVA; BEZERRA; SANTOS, 2017, p. 2).

The new proposal for an educational model guided by the Brazilian edemocratization had two fundamental premises: to promote the critical education of the student through pedagogical pluralization and to provide schooling for all of school age, preferentially to the needs of the most popular classes (RICCI, 2003). For Zientarski and Pereira (2009), this movement of redemocratization of Brazilian education also presupposed the democratization of knowledge, access to it, guarantee of permanence in it, its management, quality and gratuity, which in practice did not happen that way.

Gradually, following the educational changes, the organization and development of Physical Education classes begin to change. According to Bracht (1999), Physical Education in primary education begins to interact with the fields of social and human sciences, through a critical analysis of the competitive and technicist model. The main point questioned was the social function that Physical Education occupied in primary education. It was through discussions of educational policies that psychomotricity12 was included and used in the 1980s, and introduced to students.

[...] opportunities for movement experiences to ensure their normal development, so as to provide the children their movement needs. Its theoretical basis is essentially the psychology of development and learning [...] (BRACHT, 1999, p. 78).

Evidence points out that in the 1980s in Caxias do Sul, the teaching of Physical Education was also developed according to the precepts of psychomotricity, however, another modality that gained space in primary schools was indoor soccer13, even though it is not in the law as a compulsory curriculum component. This occurred due to the physical spaces for Physical Education classes, the weather conditions and also the number of students needed to form teams (FONSECA, 2010). For the author, in the 1980s, there was the perpetuation of sports without competitive characterization and the growth of athletics, given the low need for materials and also the possibility of apprehending a vast motor experience by the students.

Another point highlighted in the city refers to the construction of new buildings for school groups or the improvement of existing ones. Thus, the schools received new and/or better physical spaces, some with adequate courts for Physical Education classes, others, as GGS, only a patio paved with concrete. The teaching materials offered to the teachers were also expanded, which enabled the organization and insertion of new educational possibilities in the classes (GIACOMONI, 2018).

Having presented the two educational contexts to which primary physical education was linked, it is also noteworthy that the teachers Jacira and Jaqueline had educational records with a generalist formation related to this field. Thus, in the city of Caxias do Sul, as in much of the country, the teachers who were trained in teaching schools and worked in primary education, including GGS,

[...] received a minimal training regarding the area, as during their training as teachers they had little learning about the issue of Physical Education. The only subject related to the teaching of Physical Education was the so-called Physical Education Didactics, where future teachers already knew the contents that they should develop in their classes. Thus, there was very little initial teacher education that was taught in municipal primary schools (FONSECA, 2010, p. 540).

Therefore, there were differences in the ways of organizing classes and practices of primary physical education in the 1970s and 1980s. During the 1970s, nationwide, the classes were organized and developed with attention focused on sports, especially soccer and volleyball, however, at the municipal level teachers used the games and sports in an adapted way without the competitive and technical bias. In the 1980s, the new educational approaches sought a pedagogical expansion regarding Physical Education classes, which was possible due to the better physical spaces and the expansion of didactic materials, providing the consideration of psychomotricity in the organization of Physical Education classes. Sports, however, maintained their prominent role, and primary teachers continued to receive incomplete training in the field of Physical Education.

Memory of physical education classes and practices at Giuseppe Garibaldi School (GGS)

This section intends to recompose one of the possible historical versions of Physical Education at GGS's primary education by directing attention to the classes and practices organized and developed by teachers Jacira and Jaqueline. Despite the social, political and educational contexts, we emphasize that the teachers' memories about their Physical Education classes and practices at GGS showed singularities and specificities when compared to the national level.

To understand these processes it is necessary to reiterate that the teachers Jacira and Jaqueline did not have a specific formation in the area, which may have restricted the practical possibilities to the knowledge linked to the exchange of information with other teachers, readings of books and magazines and/or courses taken. In addition, GGS spaces in both the old and new buildings did not provide favorable conditions for the development of classes. Added to this fact, still they coped with the scarcity of didactic materials (JACIRA, 2017; JAQUELINE, 2017).

GGS, inaugurated in 1974, remained only for two years at the house of Mr. João Neves. The building was made of masonry and the inner walls made of wood, there were three classrooms, attended by about 90 students in the morning and afternoon shifts. The school spaces for Physical Education classes were in a gravel yard or in the classroom itself, and the materials consisted of a few balls and ropes (EMEFGG, 1974; JACIRA, 2017). According to Gatti Júnior (2000), school spaces are not neutral places as they are formed by students, teachers, staff, objects and materials, which are interrelated, which have bonds and meanings that are employed by these subjects in these spaces, allowing possibilities or limits for schooling processes.

From these perspectives, Physical Education classes began to be taught by the principal and also teacher Jacira Koff Saraiva in 1974, who gave basic guidelines on how to organize these classes. Basically, Jacira (2017) mentions in her narrative that “[...] the local government gave the books according to the grade and we followed the books [...]”. According to Luckesi (1994), that narrative has characteristics of a technical planning of teaching, linking teachers as transmitters of knowledge, thus, students interacted and acted critically little in the classroom.

According to Jacira (2017), most of the classes taught by the primary teachers were directed by oriented or free play, and when there was the possibility of using the gravel patio, sports were preferred. Eventually, there were structured classes with organized lesson plans with content linked to gymnastics or athletics. She reiterates that the purpose of these classes was not to train athletes, to exclude students who could not perform the activities, and that there were no distinctions between genders, as they all performed the same activities, each in their own time and manner.

Thus, we understand that competitiveness was not considered since Physical Education “[...] was simply part of it, because it was good and, of course, physical activity is extremely important, but it was never linked to exigence [...]” (JACIRA, 2017). Classes were held once or twice a week in the gravel yard when the weather was favorable or inside the classroom when it was raining or very cold. In addition, evidence points to the fact that a monthly class was structured with the composition of a lesson plan and specific objective, defined by the primary teachers (JACIRA, 2017).

Faria Filho and Vidal (2000) point out that the adaptation and improvisation of school spaces was accentuated in the 1950s and 1960s, as the government sought to simplify and save on the construction of school buildings, indicating changes in educational conceptions about these spaces. Thus, the school spaces became functional environments, designed for a fast and efficient education, which besides the classroom had specific places to welcome teachers and staff.

Moving forward into the 1980s, GGS now occupies another physical space, inaugurated on November 14, 1976, near its former facility. This masonry building is comprised of two floors and larger, airy and bright classrooms. However, there are still no specific courts for Physical Education, and as a resource, teachers start to use the covered concrete floor patio to develop their classes (EMEFGG, 1974; JAQUELINE, 2017).

As portrayed by Jacira in her narrative, Jaqueline (2017) recalls that there were also textbooks provided by the local government, however, they had greater freedom of organization and performance in their classes. Most of these classes were held in the covered patio, regardless of the weather and with weekly frequency ranging from two to three times. According to Ribeiro (2004), the new school spaces should be characterized by pleasant places for students and teachers, as these environments can be limiting or facilitate the schooling processes as well as the social and cultural relations between the subjects that permeate it.

The sports practices still have protagonism in relation to the other activities, mainly through soccer and volleyball, and also in adapted form, without the competitive and technical characterization. On the other hand, sports were also developed when the teachers did not want to teach the Physical Education class, so they took the students to the school yard “[...] to play, let's say a long break, so it didn't help to physically develop the students” (JAQUELINE, 2017). For Silva (2010), the playground is an informal moment for practices linked to Physical Education since they do not have direct intervention of teachers.

However, some significant changes are evident regarding the organization and planning of Physical Education classes, as primary teachers begin to worry about practices that involved students with “[...] broad psychomotor skills to develop well and to leave the care for the fine psychomotricity to be worked in class. So we wrote the letters on the floor and they passed over, they didn't like it, they wanted to play, to run” (JAQUELINE, 2017).

Through Jaqueline's narrative, indicators of a concern in her classes with the components of wide and fine motor coordination were noticed. We understand that these practices of Physical Education were directed to students as a result of their teaching training, understanding it as a field that enables the development of schooling processes in an interdisciplinary way, as well as favoring the physical, cognitive, affective-emotional aspects and also contributing to the formation of personality (FONSECA, 1988).

Inserted in the Physical Education classes, there were also the games, directed by the conducting teacher 14 or freely, which was understood as a moment of "energy release" of the students. Despite the findings of Fonseca (2010), we found no evidence of indoor soccer practice at GGS. For Bracht (1999), some of the factors here displayed led the school Physical Education to a lack of identity in this period, generating conflicts about its educational purposes and threatening its presence in schools, since it did not have its own theoretical body and inconsistent data on the field were disseminated.

Thus, regardless of the legal requirements, we understand that the teachers were aware of the importance of these practices for the formation of students in their various contexts, and not only for the physical aspects, but for the construction of a “[...] whole of knowledge and practices, values and behaviors that configure senses and meanings linked to focused body practices and built by this social practice within the school institution” (RODRIGUES; BRACHT, 2010, p. 94).

From the above, we realized that the teachers Jacira Koff Saraiva and Jaqueline Gedoz Vita organized and developed their Physical Education classes through games aimed at leisure, adapted sports without competitive bias and were limited by lack of training in the area, by school spaces and by the teaching material which was offered. Even so, there is an evident teaching effort to follow the plans proposed by the law, to find educational solutions both concerning spaces and materials for a satisfactory development of Physical Education classes.

Final considerations

Research in the field of the history of education which links different scopes and contexts makes us (re)think about the similarities, differences, permanence, singularities and their relationship with the Physical Education teaching processes in the primary grades. Thus, from the memories of teachers Jacira Koff Saraiva and Jaqueline Gedoz Vita, it was possible to know, understand and analyze a little more about the forms of organization of classes and Physical Education practices in primary education at GGS in the city of Caxias do Sul during a period of the military civil regime.

The narratives of teachers Jacira Koff Saraiva and Jaqueline Gedoz Vita about the years 1974 to 1985 show that the Physical Education classes in primary education at GGS were organized and developed from a pedagogical proposal, as they followed the books provided by the local government or from their own knowledge on the subject but not from nationalistic aspirations. Despite their distinct formative conceptions and the two places and school moments, many memories evidenced by the interviewees were similar regarding physical education classes and practices.

Regarding the physical spaces for Physical Education, we emphasize that in both school buildings there were no suitable places designated for these classes. Thus, at GGS's former school facilities, teacher Jacira had two options: the gravel-covered dirt floor or the small classroom built by the neighborhood's own residents. In the new building, there were no specific blocks for Physical Education, but teacher Jaqueline had two advantages over the old space: a covered patio with concrete floor, and large, well-ventilated and bright classrooms.

The school also lacked teaching materials for the development of Physical Education classes, as they had only a few balls, hula hoops and ropes. The other materials were always adapted from plastic bottles, metal cans, broom handles and the like. They refer that they were not obliged by their superiors, be it from school or from the Local Department/Office of Education, to teach the subject of Physical Education in the primary grades, but in their understanding they considered it important for the development of their students.

Analyzing the narratives, the period of formation of the teachers and also of their subsequent formations, we can assume that: Jacira had a technical background that ended up not being reflected in her practices, given the choice of games, sports in an adapted way, perhaps justified by the limitations of space and materials. Teacher Jaqueline, on the other hand, had direct influences from the field of the school subject of Physical Education in her teaching training, as well as from the courses and the social and didactic exchanges between schools and teachers, which provided the insertion of new educational possibilities for students. We emphasize that both teachers lived in different contexts, spaces and times at GGS, which also influenced the ways of organizing their classes and practices.

Therefore, despite the difficulties encountered by the primary teachers of GGS, we consider that the students obtained a satisfactory use of Physical Education classes within the possibilities presented in that period. The physical spaces and the teaching materials were limiting of the educational processes, but surpassed by the intense initiative of the teachers in the search of work methodologies for their Physical Education classes, besides the exchange of didactic and pedagogical materials for the constitution of these classes between the schools and also among these same primary teachers.

text in

text in