In addressing school culture as an object of historical investigation, Dominique Julia underscores the importance of analysis based on a broader context, which includes relations with other cultures, be they religious, sociopolitical or socializing (JULIA, 2001). The school culture, thus, would encompass both the norms related to the knowledge to be taught and behaviors to be instilled, as well as the ways of transmitting knowledge and internalizing behaviors according to each historical context. This broader concept gave rise to the notion of school material culture (VIDAL, 2005; ALVES, 2010), which comprises a vast repertoire of objects, buildings, furniture, manuals and teaching materials. To this last category, we add the notion of school visual culture (POSSAMAI, 2015; KNAUSS, 2006), because it points to the specificity of visuality within the school and is closely linked to material culture, since images have always been linked to the objects that configure them. Research of school materiality and visuality, however, cannot be limited only to the intrinsic properties of objects and images or to what is conventionally called the "history of objects" (MENESES, 1992). As evidenced by several studies (ALVES, 2010; VIDAL, FARIA, 2005; SOUZA, 2007), material and visual objects are the result of human work, originating from social relations; they are linked to school practices and involve representations of various aspects of school culture.

Based on these conceptions, the notions of school material culture and school visual culture allow us to circumscribe specific research universes related to a variety of objects and images that were part of a person’s education. In this sense, the work of researchers such as Antonio Viñao (2010), Augustín Escolano Benito (2010), Elomar Tambara and Eduardo Arriada (2012), Margarida Felgueiras (2005), Paulo Knauss (2006), Ulpiano Bezerra de Meneses (2005) and Zita Possamai (2009, 2012, 2014, 2015), among many others, offers relevant contributions to the understanding of the history of education from these perspectives. However, it is not always possible to have access to the material and visual objects produced by the school culture over time, adequately preserved as an educational heritage. Even collections stored in educational institutions tell us little when dissociated from their context of production and circulation and from the practices that have given them usefulness and meaning. Inserting these objects into a visual dimension present in the social whole (MENESES, 2005) could aid in the search for a richer historical interpretation. In this sense, it is important to transcend what is visible and identify what is hidden from view and what it has to say. From this perspective, the search for clues, signs and traces is unavoidable as a methodology to tackle the written and visual documents available to us, whose production aimed a "desired school" (POSSAMAI, 2015), built in words and images, according to the ideals of social, scientific and economic progress of the positivism prevailing in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Given these premises, this paper analyzes public education in Rio Grande do Sul during the First Republic and its entanglements with the so-called "modern pedagogy"2 by investigating the material innovations that occurred in the state’s schools between the end of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the 20th century. Transformations directly linked to the adoption of a new teaching method, the intuitive method3, which by adopting the "object lessons" strategy provided a leap not only methodological, but also technological in terms of classroom materials and school furniture, which began to follow international sanitary standards.

The perspective we present here is the result of our study of the reports of the Secretary of State for Home and External Affairs between the years of 1891 and 1928, located in the archive of the Legislative Memorial of Rio Grande do Sul. These documents contain the reports of the Public Instruction’s inspectors general4 João Abbot (1891-1894), Manoel Pacheco Prates (1894-1911) and Fernando Gama (1911-1928), as well as the impressions of the secretaries José de Almeida Martins Costa Junior (1891-1892), Possidonio M. of Cunha Junior (1892-1894), João Abbot (1894-1904), José Barboza Gonçalves (1904-1905) and Protasio Alves (1906-1928). The methodology used includes a critical appraisal of the reports’ content, its critical assessment in relation to other documents (laws, decrees and product catalogs) and also with the specialized bibliography regarding the historical and social context of the time in several Brazilian states and also in several countries. Thus, it was possible to observe that practices related to the production of school material culture by the public instruction institutions of Rio Grande do Sul point to circulations and transfers of ideas, knowledge and objects between Brazil and other countries, thus enriching the transnational study of education history (PATEL, 2015; MATASCI, 2016; DITRICH, 2013).

“Pedagogical modernity” and the arrival of the new at Rio Grande do Sul

The first post-Empire survey on public education in Rio Grande do Sul fills the few pages of the Report of the Secretary of State for Home Affairs of 1891 and presents the situation found by the Rio-Grandense Republican Party (PRR) at the time of the Proclamation of the Republic. On November 15, 1889, there were 685 public classes, broken down into three grades - first (632 classes); second (34 classrooms); and third (19 classes) - with an estimate of 15,120 students enrolled. This separation by grades changed on September 9, 1891, when a provincial government act abolishes the second and third grade programs and all classes end up united in first grade5.

The 1893’s report shows the changes occurred in the Public Instruction in relation to this initial picture and over a period of two years. Under the direction of João Abbot and the interim administration of J. P. Henrique Duplan, the number of public classes provided increases to 747, out of 839 existing ones. In the same period, the Normal School had 187 enrolled: 93 in the Preparatory Course, 37 in the first year of the Normal Course, 39 in the second year and 18 in the third year.

In 1894, João Abbot became Secretary of State for Home and External Affairs (1894-1904). However, before this, in 1893, he divides the state into three school zones, under the responsibility of a fiscal body composed of nine members, three in each zone, "in order to exercise permanent supervision;"6 with the divisions of classes into four grades. It was the duty of the inspectors, besides supporting schools and teachers, to report to the Inspectorate General of Public Instruction any irregularity or dissonance with the positivist principles7 applied to the education system. As explained by Berenice Corsetti (1998):

The education authorities of Rio Grande created school councils, composed of heads of households whose children attended the schools, who performed, free of charge, various inspection tasks, an activity that was considered as "a relevant public service." Among those tasks was the monitoring of teachers’ moral and civil behavior, the examination of bookkeeping, enrollment, attendance and school discipline, the examination of the students, to verify their advance, as well as the monthly certification of teachers' activities, so that they could receive their salaries, among other duties. The system was complemented by the visits of the school inspectors, surrounding the school with permanent surveillance, with significant savings of resources. This system, also marked by administrative centralization, underwent improvements over the period. School councils became school districts, which kept members of the communities engaged in unpaid activities. The school inspectors were gaining more technical specialization, which was the innovation established at the end of the period. This entire service was coordinated by the Director General of Public Instruction, who gathered, within the Secretariat of Home and External Affairs, the information that enabled the broad knowledge and control of the Rio Grande educational sector. (CORSETTI, 1998, p. 66)

From this perspective of control, the state, since the early years of the Republic, places itself as responsible for the selection and provision of the material necessary for public classes. In 1893, Secretary Cunha Jr. presented a list of the materials provided: "books, paper, ink and other objects necessary for teaching in public schools, in accordance with the extension of the respective agreement signed with Rodolpho José Machado" (RIO GRANDE SOUTH, 1893, p.11). The items were sent to all schools of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande, São José do Norte, Pelotas, Jaguarão, Santa Maria, Cachoeira, Rio Pardo, Santa Cruz and São João Batista de Camaquã.

Teaching materials became a matter of greater attention as of 1896, when the new Inspector General of Public Instruction, Manoel Pacheco Prates, suggested the state should replace the books used in the first school grades with wall maps, a measure considered more economical and more in accordance with what he called "modern pedagogy," related to the intuitive method and the object lessons. Based on the law that reformed the Public Instruction in the State of São Paulo8, Prates writes its first bill for the Public Instruction of Rio Grande do Sul, providing for the centralization of the acquisition of furniture and school materials in the Inspectorate itself, an activity hitherto undertaken by the State Treasury.

Decree no. 89, dated February 2, 1897, reorganized the primary public education of Rio Grande do Sul and determined, according to the instructions of the primary education program prepared by Prates9, the adoption of the "intuitive and practical method" and "all important achievements of modern pedagogy," in order to establish a "rationally applied and uniform system of education." The writing of the program, inspired by experiments carried out in the United States and Argentina, was assisted by Professor José Theodoro de Souza Lobo10. According to the report of Manoel Pacheco Prates:

As for the pedagogical part, the most important achievements of modern pedagogy were enshrined. In the instructions, I followed as far as I could the American legislation, advantageously applied in the Republic of Argentina; I was careful to make the profound modifications demanded by our conditions and by the State Constitution. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1897, pp. 404-407)

In his reform, Prates returns to an idea he already proposed in the report of 1896: replacing the books used in the classroom with wall maps. To this end, he suggests the state obtain the rights to edit and reproduce the wall maps, the Cartilha Maternal (maternal guidebook) and the Livro de Deveres dos Filhos (book of children’s duties) by the Portuguese educator João de Deus Ramos Nogueira11, through direct negotiation with his widow in Lisbon.

In 1898, Prates asked the state’s Chamber of Representatives money for purchasing desktop world globes, maps, collections of teaching drawing books, object lessons teaching materials and geometric solids, which would be provided only to classes whose teachers had recognized competence12 in teaching by the intuitive method. He mentioned that the Public Instruction, among other books, adopted and distributed the Object Lessons textbooks by Saffray13, which he aimed to replace with wall charts over the following years. The charts would be organized by the 2nd Region Inspector, João Pedro Henrique Duplan, who died in 1899.

The following year's report (1899) established the logistics of distributing teaching materials to schools: teachers sent their requests to regional inspectors, who, based on the knowledge of the needs of the schools assigned to them by the government, made the changes they thought appropriate. Then a general map with the names of the teachers and the material needed for each school was produced. Based on this map, the material was distributed, and their receipt should be signed by the requesting teacher on the invoice accompanying the supply.

The Inspector General's report dated June 1, 1899, contains a list of the works and objects received by the Public Instruction warehouse and distributed as of that year to the schools. The books were the following: Cartilha Samorim; Segundo Livro Samorim; Terceiro Livro de Leitura - Na terra, no mar e no espaço and Quarto Livro de Leitura - Pátria e dever, by Hilário Ribeiro; Seletas, by Alfredo Pinto; Cartilha João de Deus; Livro de Deveres dos Filhos, by João de Deus; Primeira e Segunda Aritmética, by Souza Lobo; Corografias, by Henrique Martins; geography textbooks by Souza Lobo and by Henrique Martins; História do Brasil, by João von Frankenberg; História do Rio Grande do Sul, by João Maia; grammar textbooks by Bibiano de Almeida; Catequismos, by Dr. Lacerda; Cânticos Infantis; and Lições de Coisas, by Dr. Saffray. The objects were 50-sheet blank notebooks, reams of lined paper, reams of plain paper, collection of traslados14, wooden and brass pens, Faber pencils, feather boxes, ink bottles for students and teachers, metric rulers, ink (liters), stone pencils, chalkboards, chalk boxes, sponges (kilos), bells, water filters, agate mugs, blotting paper and agate and porcelain urinals.

The lists contained many items Prates considered outdated, such as Dr. Saffray's Lições de Coisas; it took some time for the stock of the Public Instruction warehouse to be updated according to the "modern pedagogy" instituted as a teaching method by Decree no. 89 of 1897. In 1898, the inspector general asked the Chamber of Representatives for the acquisition of material for the object lessons, as previously stated. In 1900, he explains to the Secretary of Home and External Affairs, João Abbot, the reason for the delay in launching a public call for purchasing intuitive teaching materials: the high price of the objects, all foreign-made. Two years later, Prates reiterates the need for more funds for buying books and materials, such as Levasseur's map of Brazil and charts of geometric figures by Ezequiel Benigno de Vasconcellos Junior, again emphasizing his intention of distributing them to 903 elementary schools.

In 1906, the public health physician Protasio Alves is sworn state secretary of Home and External Affairs. The decree n. 874 of February 28 of that year, based on the work of Prates, establishes new regulations for the Public Instruction and abolishes the District Colleges, replacing them with the Complementary Schools, institutions with the dual purpose of providing complementary education to all who desire it and training teachers.

Following the plans drawn up for the Public Instruction, Alves informs the governor, Borges de Medeiros, in 1907, of the purchasing order for "appropriate devices," among them "wall charts for teaching reading to elementary classes by the classic method of João de Deus"15. There is also the beginning of a move to replace the schools’ furniture, judged in disagreement with the prescriptions of science. For this, he orders the making in the workshops of the House of Correction of Porto Alegre of chairs and desks in several different heights. He also orders two thousand desks, along with chairs, to the American Seating Company16, based in the United States.

In their study of material culture and learning of writing in Brazil, Elomar Tambara and Eduardo Arriada (2012) trace an evolutionary line of teaching materials: from sand banks, through stone writing slabs to lined notebooks. Transformations accompanied by school furniture:

Thus, the individual desks with inclined top were indicated, which facilitated "much the regularity of the traces and, therefore, the evenness of the letters." Without any embarrassment, the benches and chairs manufactured in any carpentry workshop in Brazil were replaced by cast iron furniture imported from the United States and Europe in the name of the modernity of the teaching-learning process. (TAMBARA; ARRIADA, 2012, p.85)

In his next report (1908), Protasio Alves, whose work in the Public Instruction is much more active than that of his predecessor, states:

School hygiene has improved. It has disappeared from the schools of the Capital that anachronistic furniture, which was replaced by elegant desks that fit the height of the children. I ordered to cease the distribution of desks, as has been done, of uniform size. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1908, p.10)

In 1910, the House of Correction workshops - which were not being able to meet the demand - supplied tables, platforms, cabinets, desks, benches, armchairs, ordinary chairs, tools for calculations, shields, hangers. The list17 with the quantities distributed and the cities benefited is on page 171 of the Public Instruction Report presented by Manoel Pacheco Prates, who was inspector general until 1911, when he took up the chair of Civil Law at the São Paulo Law Academy (Editor, 1938). He was replaced as the head of the renamed 3rd Directorate of the Central Office by career officer Fernando de Albuquerque Gama, according to Decree no. 1,746, dated July 25, 1911.

Under the administration of Protasio Alves, a supplying alternative, less expensive than imports to the public coffers, is found: the local (re)production of international models. This activity was not restricted only to furniture and objects, but was extended to books, among them those published by Livraria Selbach in Porto Alegre, such as the Cartilha Maternal ou Arte de Leitura - Método João de Deus and the book História do Brasil by João von Frankenberg. The norms for publishing school textbooks and reading books - including those regarding language, approach, printing, material, finishing and binding - are in the 1913’s report, pages VI to VIII, and establish in broad lines that "school textbooks should be printed in black ink, on good paper, slightly yellow, not glossy; they shall not be bulk and shall be sewn with line and not stapled.” They should be easy to read and start from the "known to the unknown," and in addition:

Preferably, subjects should relate to our people and our things. Our nature, our homeland geography and history, the life and deeds of the great benefactors of humanity; the most important discoveries and inventions will provide the content for such books. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1913, page VII)

In 1911-1912, Protasio Alves organized an "inventory of the state’s school furniture" (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1912, page IX), a document that would be in the possession of his Secretariat, but that does not integrate the reports researched. In the 1912 report, he records the delivery of three thousand double desks, "Triumph type"18, from the American Seating Company, to 15 elementary schools (Bagé, Canguçu, Arroio Grande, Santa Maria, Rio Pardo, Santa Cruz, Taquari, Bento Gonçalves, São Sebastião do Caí, São João de Camaquã, São Jerônimo, Encruzilhada, Passo Fundo, Caxias, São João do Montenegro) and urban schools of nine cities (Rio Grande, Pelotas, Jaguarão, Santa Vitória do Palmar, Uruguaiana, Itaqui, Quaraí, São Borja, Santana do Livramento). Based on this model, considered revolutionary for the time, Alves orders the House of Correction19 to manufacture similar ones that, instead of being made of maple wood and cast iron, are adapted to the local reality and produced with native wood and beaten iron.

In the 1912’s report, the secretary also informs about the provision for the special instruction of indigenous peoples of "besides the usual school supplies, cereal seeds to serve agrarian instruction [...] and devices to serve as attractions through enjoyable amusement, such as gramophones with appropriate songs and lectures" (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1912, page VII). Regarding the new acquisitions for the schools, he informs of the arrival, together with the furniture imported from the USA, of globes for the study of cosmography and green screens to replace the blackboards. Along with the shipment of ordinary school materials, all educational institutions received geographical maps of the state and Brazil (Olavo Freire edition, for junior high school, ordered from Francisco Alves & Cia.20). The following year (1913), the schools received geographical charts of the five great parts of the world, edited in Portuguese by House Jablonski21, of France.

The reports make many references to the practices adopted in the United States, Europe, Argentina and Uruguay (a country to which a state’s teacher delegation was sent in 191322), as well as comparing the regional situation with that of states such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Among them, the overhaul of public instruction and the study of the German national, mentioned by Manoel Pacheco Prates as a model of "teaching direction unit" (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1897, p.403) and the adoption of methods such as the intuitive and the Sloyd, aimed at the manual arts and that, according to an explanation of Protasio Alves to the governor Borges de Medeiros:

The Sloyd [method] transplanted to North America in 1888 by the Swedish professor Larrson, who came to teach it in Boston, developed to such an extent that today exceeds what is done in its country of origin. The 'object lessons' are part of our education programs; ... the manual arts are its complement (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1909, p.11)

We can observe the attention given to the pedagogical innovations in circulation in other Brazilian states and in other countries, especially regarding the development of a market for school products for the public education project. When the Public Instruction was not able to purchase the products, due to high costs, local manufacturing alternatives were sought, which was the current practice in other countries. Thus, between 1911 and 1912, a thousand school collections were ordered, with 130 items each, from the Júlio de Castilhos Museum (POSSAMAI, 2012, p.10). Charged by the inspector general Fernando Gama to coordinate the activity, the director of the institution, Francisco Rodolfo Simch, creates school museums23 containing:

[...] samples of the minerals most common in the State, fragments of stones, earth in glass jars, with their proper descriptions, in order to be distributed to the students of our schools so that they may have a rudimentary knowledge of mineralogy. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1912, p.230)

This "home-made" production of school museums for the object lessons learning activities is not an unprecedented solution in the history of education. In Argentina, which inspired some of the changes in teaching adopted in Rio Grande do Sul, there were several initiatives undertaken aiming to produce teaching materials more suitable to the local reality. This is the case of the projects of the Italian Pedro Scalabrini (1880-1900) and of the Argentineans Guillermo Navarro (1895) and Carlos M. Biedma (1908). According to research by Susana García (2014), the Museo Escolar Argentino, or Museo Scalabrini, had the form of school boxes containing "between 50 and 100 samples of minerals, woods, fossils, mollusks, bones and other natural products of the coast of the country, each object constituting a lesson in natural history" (GARCÍA, 2014, p. 78). Navarro’s Museo Escolar Nacional was composed of a cedar cabinet containing nine large boxes and about a thousand samples, following the French example, and emphasized national industries and potential productive resources. Biedma’s Practical System of School Museums consisted of 35 models with reproductions in plaster, cardboard and paper of geographical accidents and the main historical, ethnographic and industrial feats of Argentina, as well as charts and scale models. These initiatives originated institutions such as the Pedagogical Museum of the Province of Buenos Aires, the Popular-School Museum of Las Conchas and the Sarmiento School Museum.

Other associations of the method chosen for public education in Rio Grande do Sul and its application with the logic of museums appear in the reports of 1916 and 1917. In the first, Protasio Alves mentions the holding of annual exhibitions in Porto Alegre and in complementary schools that exhibited handicraft done in the classroom. In the second, he mentions "industrial museums" to be established by and in industrial schools and zootechnical and agricultural stations associated to courses of Veterinary Medicine and Agronomy (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1917, p. XIII). The latter need to be better investigated.

Until the end of the administration of Borges de Medeiros, Protasio Alves continues to report the purchase, manufacture and constant delivery of furniture and teaching material to public schools. In his 1927’s report he states that:

School supplies were regularly and carefully supplied to public establishments, although it was found that the money approved for this purpose was insufficient. The material is distributed on request for each establishment that does so, taking into account the vacancies and the enrollment of poor students. The considerable increase in the number of educational establishments and in the attendance of those who have been operating in previous years has demanded more pieces of furniture than it is possible to produce in the workshops of the House of Correction, so it is necessary to purchase furniture for supply. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1927, p. XX)

However, it was his successor, Osvaldo Aranha, who presented to the new president of the state, Getúlio Vargas, an overview of public education from the ideological point of view of the PRR, since the proclamation of the Republic to the last day of Protasio Alves as secretary of Home and External Affairs:

We have been able to disseminate thus a useful, fruitful, intuitive teaching and a physical, civic, hygienic and social education. We do not teach to read, but to learn, live and work. Each child that this school integrates into social life will be a potential for immensely reproductive work and progress, both from an economic and a financial point of view. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1928, p.33)

Based on the lessons received from Protasio Alves and continuing the work of his predecessors, Aranha suggests measures for a systematic plan for reforms and action, such as the creation of the Board of Public Instruction; the reform of complementary education, with the creation of new introductory and teacher training schools; the increase of the budget for purchasing school materials; and the creation of the Revista do Ensino (teaching magazine), among other measures.

Rich in information presented in tables, maps and charts, the Reports of the Public Instruction of Rio Grande do Sul offer indications of the school material culture produced and acquired by governmental instances in line with the prerogatives of what was considered a modern pedagogy. Studying the practices among subjects within the school space using these objects is a more complex task suitable for the history of education. Photographic images, in this sense, may offer some clues.

The classroom as an image of progress

Photographs can be rich documents to capture the material culture of the school, which itself is the product of school visual culture. For this, we follow Knauss (2006) when he points out that:

When we refer to institutions, it is important to observe the organized social relations around the production of the image and its circulation. Bodies, in turn, remind us of the need to consider the presence of the observer, the viewer, as a necessary "other" in the circuits that promote visual meanings, and that someone guides the control of the image. The plan of figuration does not allow us to forget that the images have a privileged role in the sense of representing or figuring the world in visual forms. [...] The dialectic between seeing and not seeing questions the knowledge as the fruit of the sensible, arguing for a bridge between the fact and the abstraction that allows one to see where others do not see. It is a matter of defining one’s look as thought and making it the matter of historical knowledge. (KNAUSS, 2006, pp. 114-115)

The reports studied have few photographs. The only series of illustrative photographs of public schools and their activities are in the volume relative to the year 1924, whose images are in the photo/caption format, without identifying the author, who probably was a professional hired for this function. In the reports, these images aimed to document the progress made by the PRR government through the adoption of innovations and trends identified with "modern pedagogy" by the public education managers. Therefore, we included other images from museum collections and commemorative albums in our study.

According to the perspective presented in this paper, we selected four photographs: two of classrooms and two of the carpentry and metalwork workshops of the House of Correction, chosen for their documentary and illustrative purpose and also for the representative character of the interaction of students, teachers and workers with teaching objects and furniture. The concept of "desired school" is used here as proposed by Possamai - the idea of a "rational and modern scientific education within the republican aspiration" (POSSAMAI, 2009, p.940) - whose ideas were reinforced by photographic representation, made in order to construct the image of a school-monument.

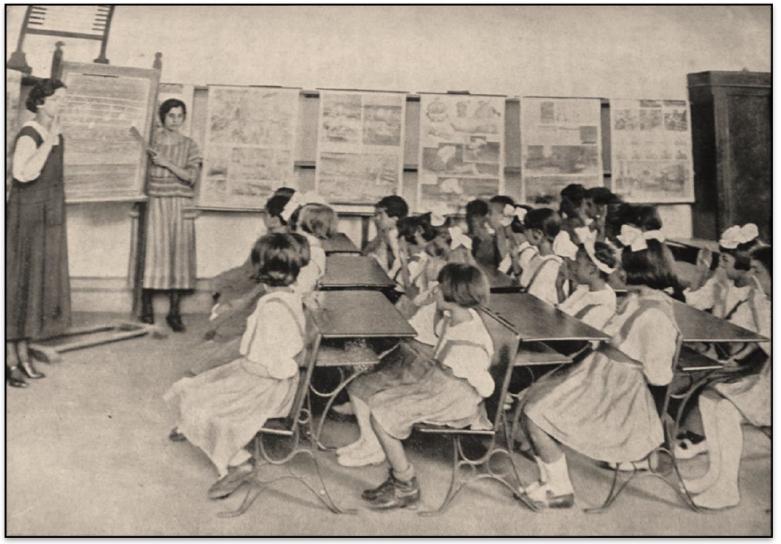

The first of these is of a practical class at the Complementary College of Porto Alegre, an institution defined as a "model school" by Protasio Alves since the beginning of his administration as secretary:

Complementary schools are excellent establishments of instruction. The one that was located in Porto Alegre, with its own building and other improvements, which I hope to see implemented soon, will be a model school. Appropriate equipment has already been ordered so that it will provide the most comprehensive teaching. The learned director, as soon as he receives the wall charts, will personally begin to teach reading to the elementary classes by the classic method of João de Deus, incomparable when well applied, which until now has not been done here. These lessons will be attended by the students of the higher education course, who will be teachers and go to elementary classes to learn the teaching technique. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 1907, p.11)

In the image, students preparing to be teachers are in front of a class of children and observe the methodology used to educate them. Aside from the caption accompanying the photograph, there is no more information about the activity and daily life that it represents. Images such as this one, in which aspiring teachers position themselves in front of the class and not amid the students, observing the teacher, are uncommon, deserving further, more accurate studies of what the photograph below represents to the training of teachers at the time.

In relation to school material, one can see, at first, the ample and illuminated environment, besides the sets of Triumph-style chairs and desks and a system of interchangeable chalkboards. The children, all in white uniforms, have their tables empty and all show the same posture, with their hands folded in their lap. The teachers in training take note, while the focus is on the performance of the class teacher.

Source: RIO GRANDE DO SUL. Report presented to the Illustrious Mr. Dr. A. A. Borges de Medeiros, President of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, by Dr. Protasio Alves, Secretary of State for Home and External Affairs, on September 6, 1924. Porto Alegre: Officinas Graphicas d'A Federação, 1924. Collection of the Legislative Memorial of Rio Grande do Sul.

Figure 1 "Complementary School - Capital. Practice Class." No attribution.

The second image depicts a singing class at the Elementary School in the municipality of Cachoeira. In terms of the material and visual culture represented, it is the richest. In addition to the benches and desks, we can see a wall with three levels of shelves, filled with wall charts and an abacus, and a large cabinet at the back of the room. We can infer that the cabinet contains one of the school collections of the Julio de Castilhos Museum, as well as materials such as books, geometric solids and maps. One of the teachers points with a ruler to a chart in a holder, probably showing a song, while the other makes conducting movements. The children are in uniform and sitting with one hand behind their backs and the other raised, making the same gesture as the regent.

Source: RIO GRANDE DO SUL. Report presented to the Illustrious Mr. Dr. A. A. Borges de Medeiros, President of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, by Dr. Protasio Alves, Secretary of State for Home and External Affairs, on September 6, 1924. Porto Alegre: Officinas Graphicas d'A Federação, 1924. Collection of the Legislative Memorial of Rio Grande do Sul.

Figure 2 "Elementary School of Cachoeira - A group of students in a music class." No attribution.

These photographs differ from others also included in the governmental reports produced in the same republican context that aimed to document actions and public works carried out in the year before. A previous study (POSSAMAI, 2009) points out that images of school buildings were the most common in the reports of the Public Instruction of Rio Grande do Sul, since these were especially aimed at showing the construction works underway or carried out by the state government.

In a different way, the school images presented here show the interior of the classroom, in which we can observe aspects of the material and visual school culture within their context, but also capture the subjects in action. By analyzing these images, we can see that both were produced with the purpose of showing and recording the existence of order, rules, method and cleanliness in the Public Instruction, that is, to give visibility to the school the republican political project aspired. This is apparent in the standardization of the children, not only in clothes and in the hair ties of the girls, but also in their posture. The teachers and aspiring teachers, through their posture, participate in the staging, feigning disinterest in the camera that documents their activity. The exception that exposes the scene is the look of a teacher in training in the first image, who looks directly at the photographer and ends up catching the eye of the observer, as if challenging the researcher to decipher what was happening then.

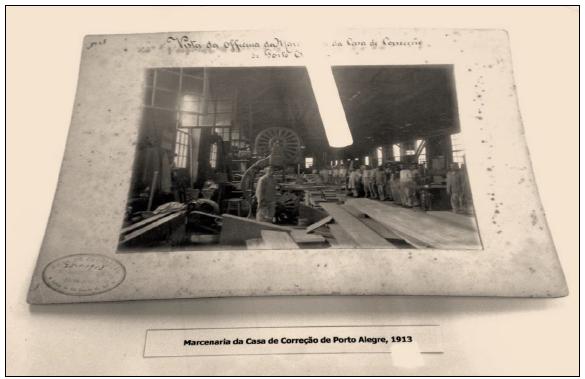

The third and fourth images studied represent the activity of inmates in the carpentry and metalwork workshops that made school furniture. In the images, the protagonists are the workshops, portrayed in open plan. In both images, the attention is drawn to the immobility of those who pose and are not photographed in activity, an aspect that demonstrates the extraordinary moment that was the photographer's presence in their work environment. The uniform homogenizes these workers and inscribes their visual identification as inmates of the House of Correction. The environments have windows and natural light, and the photographic representation gives, as in the case of the Complementary School classroom, an impression of order, rules, method and hygiene.

Source: Exhibition "House of Correction - Saying the Unspeakable," Museum Julio de Castilhos, Porto Alegre, 2017. Collection of the Museum. Reproduction Cristiane Miglioranza.

Figure 3 "Carpentry workshop of the House of Correction of Porto Alegre, 1913." The stamp reads "House of Correction, 1/25/1913, illegible part, Porto Alegre, State of Rio Grande do Sul.” No attribution.

Source: STATE OF RIO GRANDE DO SUL. [Secretariat of Public Works]. Public Works: Centenary of Independence. Porto Alegre: Officinas Graphicas d'A Federação, 1922. Collection: AHRGS.

Figure 4 House of Correction (original title). Metalwork workshops (original caption).

These images, intertwined with the written evidence on the school material culture, allow us to capture elements of the school culture, but also of the social relations within that historical context that go far beyond the school universe. Initially, the aspects of the production of school desks, which the reports specified were manufactured in the House of Correction, gave little or no visibility to the subjects who actually made these objects. The images, although circumscribed to the configurations of a photographic representation, gave visibility to these subjects. Somehow, pupils, teachers and teachers in training from the school were linked to the inmates of the House of Correction, who had made the classroom desks.

Final considerations

The new republican order in Rio Grande do Sul was marked in the Public Instruction by a centralized government with positivist characteristics. Public Instruction officers aimed to adapt the schools to a "modern pedagogy," at the heart of which was the adoption of the intuitive method as a novelty in teaching. In order to achieve the desired modernization, it was essential to acquire objects, books, wall charts and furniture appropriate to the pedagogical and health precepts, widely disseminated in other countries.

The need for materials by the teachers required the development of a process involving the assessment of the demand, the government purchase from the manufacturing companies and, later, the distribution to schools throughout the state of Rio Grande do Sul. An example of this practice was the purchase and distribution of three thousand Triumph desks from the American Seating Company, among other teaching materials.

However, it was not always feasible to acquire the materials considered more advanced, since the import from foreign companies made the prices too high for the possibilities of the state. To address this situation, educational agents embarked on the practice of manufacturing on their own, with the available resources, the objects and furniture they needed. Thus, the inmates of the House of Correction began to make school desks in the same model acquired through importation; the Júlio de Castilhos Museum produced school museums containing samples of minerals for schools, among other initiatives.

We observed the circulations and transfers of objects of material culture, as well as the ideas and the knowledge that served to Brazilian officers propose local measures for the implementation of a desired school in the mold of modern pedagogy, so advocated in their writings. Although the high prices are presented as justification for the non-acquisition of these materials, it is important to highlight the creative solutions and the peculiar practices that gave shape to a real school whose vestiges and evidence were pursued here.

The few photographic images presented in the reports of the Public Instruction show the school in different ways than other images that pictured exclusively the school buildings. In order to register in images the material culture and the design practices related to it, it was essential to see the inside of the classrooms. In this way, we were able to observe the image of a desired school and its subjects, teachers and students, in action in the order and tranquility of a class, at least while the photographer was present for the making of the extraordinary record, to be eternalized for the researchers of the present. Other clues were sought to build this mosaic of the history of material and visual culture of the past. In this sense, the photographic images of the House of Correction workshops, one of them published in an album commemorating the State Government and another found in an exhibition of the Júlio de Castilhos Museum, helped to visualize the makers of the furniture shown in the classrooms. Thus it was possible to interweave a wider culture within that historical context with the material and visual culture of the school.

The Public Instruction in Rio Grande do Sul and the material and visual culture generated by local educational activities still demand further research, especially with regard to the social memories involved, the representations, the imaginary and the material reminiscences that remain without voice in the collections of museums, waiting for research and exhibitions, or remain still invisible in school institutions, waiting for a look that values them as an educational heritage.

text in

text in