Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.19 no.3 Uberlândia set./dez 2020 Epub 26-Out-2020

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v19n3-2020-23

PAPERS

New public performances. Athletic clubs and the body education (Rio de Janeiro, 1884-1889)1

1Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil) victor.a.melo@uol.com.br

Founded in the 1870s in Rio de Janeiro, the British and American Club was the city’s first association dedicated to “athletic sports”, the beginning of athletics. The club was managed by Britons and at first only English speakers could take part on running, jumping and throwing competitions, among other games. In the early 1880s, Brazilians started competing and also organizing their own associations. The year of 1884 saw the beginning of an expansion in such activities. This study aims at discussing the experiences in athletics clubs created in the Brazilian Empire, between 1884 and 1889. Its goal was to point out how their activities worked as a non-formal process of education. The main sources used in this study were journals published in the Brazilian capital. In the end, it is concluded that sports presented new uses for the body in the public sphere, and this process included both competitors, who displayed a new muscular complexion, and the audience, who needed to learn how to dress and behave in the stands.

Keywords: History of Education; Education of the body; History of Sport

No Rio de Janeiro, fundado na década de 1870, o British and American Club foi a primeira sociedade dedicada aos “esportes atléticos”, primórdios do atletismo. Dirigido por britânicos, a princípio somente anglófonos participavam das provas de corridas, saltos, arremessos e jogos diversos. No início dos anos 1880, brasileiros começaram a também competir, bem como organizar agremiações próprias. A partir de 1884, houve uma expansão dessas iniciativas. Este estudo teve por objetivo discutir as experiências dos clubs athleticos criados na Corte entre 1884 e 1889. O intuito foi perceber como suas atividades se constituíram em um processo não formal de educação. Como fontes, foram utilizados periódicos publicados na capital nacional. Ao final, se concluiu que a modalidade apresentou novos usos do corpo na cena pública, algo que envolveu os competidores a exibirem uma nova compleição muscular, mas também a assistência que deveria aprender a se vestir e se comportar nas tribunas.

Palavras-chave: História da Educação; Educação do corpo; História do Esporte

En Río de Janeiro, organizado en la década de 1870, el British and American Club fue la primera sociedad dedicada a los “deportes atléticos, principios del atletismo. Dirigido por británicos, al principio solo los angloparlantes participaban en las pruebas de carreras a pié, saltos, lanzamientos y juegos diversos. En el inicio de los años 1880, los brasileños también empezaron a competir, además de fundar sus propias asociaciones. A partir de 1884, hubo una expansión de estas iniciativas. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo discutir las experiencias de los clubes deportivos creados en la Corte entre 1884 y 1889. La intención era entender cómo sus actividades se constituyeron en un proceso educativo no formal. Como fuentes, se utilizaron periódicos publicados en la capital nacional. Al final, se concluyó que eso deporte presentaba nuevos usos del cuerpo en la escena pública, algo que involucraba a los competidores que exhibían públicamente una nueva complexión muscular, pero también el público que debería aprender a vestirse y comportarse en las tribunas.

Palabras clave: História de la Educación; Educación del cuerpo; História del Deporte

Introduction

The structuring of an entertainment market is usually related to important changes in the dynamics of cities: a greater willingness to occupy the public space (partially due to political upheaval, but also to the circulation of new ideas about social life), and an economic strength marked by the formation of middle classes that expanded the base of consumption (CORBIN, 2001; MELO, 2010).

It is not possible to separate these entertainment settings from the expectations of marketing and transmitting new desires, elements related to noticeable changes in the productive world. As Porter (2001, p. 57) states, since the 18th century, “the history of the use of free time reproduces, (...), the general scheme of the development of industrial society, while reflecting some of its paradoxes2”.

A strain between the ideals of consumption and spectacle is noticeable. The latter is a concept that, in spite of its limits, expresses not only a new format of entertainment, but rather a new form of social dynamics, a means of establishing mediations with the reality that encompasses all human endeavors (CLARK, 2004, p. 43). Significant impacts in bodily experiences may be noticed in this scenario, marked by an intense circulation of ideas, products and people:

In all of these new systems of circulation, the drama of modernity sketches itself: a collapsing of previous experiences of space and time through speed; an extension of the power and productivity of the human body; and a consequent transformation of the body through new thresholds of demand and danger, creating new regimes of bodily discipline and regulation based upon a new observation of (and knowledge about) the body. (GUNNING, 2001, p. 40).

Entertainment is, therefore, an important historic occurrence, an expression of a determined era, connected to the social tensions of time/space. In its surroundings, it is possible to notice the impositions, resistances and negotiations of ways of behaving in public, related to the possibility of bodily exposition and the uses of the body.

This process may be seen in Rio de Janeiro in the 1880s. At the same time that entertainment-related ventures were becoming more diverse and better structured, there was a growing concern about their adequacy. The process of social distension triggered several tensions related to the usage of such amusements.

What happened in Brazil, especially in its capital, held similarities with the process in Europe3. There was (and still is) an ambiguity that surrounded the growing occupation of the public space. This excitability could not manifest itself freely, and was restricted by directives of different origins, including science. This was intensified by the fact that the body was turning into one of the main objects of intervention and investigation (FAURE, 2008).

It must be taken into account that, in Brazil, that decade was marked by an intense political upheaval, especially due to the initiatives of two groups that had become better structured: abolitionists and republicans (CARVALHO, 2012). Moreover, there was a better arrangement of different socioeconomic groups, including very heterogeneous middle classes (POPINIGIS, 2007). In the cultural sphere, contacts with the European “civilized world” had expanded (SCHWARCZ, 1998). The process of adhering to the ideal and imaginary of modernity was intensified.

At that time, some entertainment already offered the public activities marked by greater body exposure. In the first half of the 19th century, dancing societies and bullfighting arenas brought to the center of the scene a well-dressed body (MELO, 2015a; MELO, 2016). In the middle of the century, horse racing was responsible for the major sporting structures (in which rigorous clothing was still demanded), followed by rowing (in which the public, but mostly the athletes, wore lighter suits) (MELO, 2014; MELO, 2015b). Sea-bathing forged a new sociability on the beaches. They formed a more relaxed experience, even if, at first, largely regulated by moral and medical dictates (MELO, 2015c).

In fact, in the case of Rio de Janeiro, the emergence of a new set of concerns about health and hygiene simultaneously stimulated and restricted this dynamic. One of the repercussions of this process was the greater offer of content related to body education in schools, especially dances and gymnastics, which were even considered in legislation (PERES, MELO, 2014).

An indication of this new arrangement of customs, as already argued by Melo (2010), was the circulation of new terms. Among these, we can find the word “athlete”, which went through a transition during the 19th century. If at first it was used to define both those who were physically involved in combat and those who dedicated themselves to great causes, from the middle of the century onwards, it began to be progressively used to designate those who dedicated themselves to physical activities. Initially, there were no medical or educational connotations around it. It defined, for example, artists who exhibited acrobatic or force feats in the circuses. In the 1880s, however, the term was more commonly used to designate those who engaged in bodily practices with “higher” ends, suited to the ideals of civilization and progress. Regarding sports practitioners, the term “sportsman” was still used more often, a word that also applied to club officials and the audience.

This is one of the indicators that led us to take interest in the initiatives of clubs that promoted “athletic sports” competitions, that is, foot races (at the time so called to differentiate them from “horse races” and “boat races”), as well as throwing and jumping (called “athletic games”, a term that also encompassed activities in which skills were tested, such as tug of war, egg-and-spoon race or sack race).

At a time when sports were still seen more as a spectacle than as a lifestyle linked to health and hygiene, something that would become more common in the last decade of the 19th century, these early ages of athletics constituted an important experience of transition.

In the Brazilian Empire, the pioneering athletics club was created by Britons in the 1870s: the British and American Club. At first, only English speakers could take part in their competitions. In the early 1880s, Brazilians began to participate and also to create their own associations (MELO, 2019a). Beginning in 1884, there was an expansion of such enterprises.

Taking into account this initial debate, this study aims at discussing the experiences of athletics clubs created in Rio de Janeiro between the years 1884 and 1889, in a time when sport became more popular in the city, related to the strengthening of the entertainment market.

The goal was to understand how such experiences worked as mechanisms of education of the body, considered in this study, not only as more targeted interventions that occurred in formal institutions, but also as everyday initiatives related to the adjustment to customs, behaviors and ways of behaving. It is a relevant research effort to discuss “the techniques, pedagogies and instruments developed to subject them (bodies) to norms” (SOARES, 2001, p. 111).

In order to achieve this goal, journals published in Rio de Janeiro were used as main sources4. We consider that the press, a relevant forum for debates in the 19th century and an important agency in the formatting of entertainment initiatives, conveyed points of view on different sports. Those are worthy of attention for they express concerns about the suitability or not of those bodily practices.

Magazines and newspapers were treated based on the suggestions made by Luca (2005). The profile of the journals will be presented when dealing with the positions of chroniclers, considered not as expressions of absolute truth, but rather points of view to be understood in the spirit of their time. The same will not happen when referencing to factual information, unless it is considered to be related to the characteristics of the accessed title.

The growing interest in sport (1884-1885)

Starting in 1884, the process of popularizing “athletic sports” expanded, with the creation of new associations that joined the pioneering associations, which continued to promote their own events5. The British Amateur Athletic Sports remained active for some time, and their festivities were marked by the increasing presence of Brazilians in the audience and among competitors. The same happened to the Rio Cricket Club, also founded by Britons in 1880, which was mainly dedicated to cricket but also organized athletic sports events, occasions that enjoyed good public repercussions (MELO, 2017a).

In these associations, the possibility of gambling started to concern some members of the British colony when the number of events increased. Some associates even drifted away because they considered that such excesses went against the true educational feature of sports (THE RIO NEWS, 1889a, p. 3)6. In Rio Cricket, an extraordinary board meeting was held solely to decide whether or not to maintain horse betting (JORNAL DO COMÉRCIO, 1884, p. 2).

There was a concern in maintaining certain British parameters at a time when the growing contact with the Brazilian population interfered in the dynamics of the competitions7. Sport was supposed to balance between two dimensions: entertainment and education. Both were necessary for the success of the initiatives, but for some the limits should be made clearer, with greater emphasis on the second aspect.

The activities of two other pioneer clubs, both from the city of Niteroi, are examples of the goal of balancing these two dimensions: Clube Atlético Brasileiro, created in 1881, and Clube Olímpico Guanabarense, founded in 1883 (MELO, 2019b). It must be taken into account that runners from Niteroi used to take part in races in Rio de Janeiro, just like many from the nation’s capital that crossed Guanabara Bay to demonstrate their skills in the neighboring city. As more associations were created, this became even more common.

At first, there were some short-lived clubs in the Brazilian Empire’s capital that relied exclusively on Brazilian runners, initiatives that deserve to be registered because they demonstrate the vitality of the sport. When writing about the creation of the Grêmio Filhos de Tethis, an association which was also dedicated to swimming, a chronicler noticed the movement around “athletic sports”: “Some fearless and daring youngsters, disdaining the triumphs achieved in the athletics clubs as too easy, go looking for new triumphs to later decorate their heads, not with laurels, but with seaweed crowns interwoven by beautiful nereids” (O PAIZ, 1885a, p. 2)8.

Competitions contributed to making the public display of body performances acceptable or even desirable, for some, presenting new uses of the body in a city in intense change. It was not a question of running with horses (horse racing) or with boats (rowing), but of a more direct use of the body as an instrument. On the one hand, races were, to a certain extent, less exciting due to the slower speed. On the other hand, however, it promoted an exposure of bodies that had never been seen in Rio de Janeiro.

Some associations were located in the south and central regions of the city, where the entertainment market was already better structured, especially in regard to sports initiatives. Among others, it is possible to mention Grupo Atlético dos Seis, formed in 1884, promoting events at the Passeio Público (a public park in Downtown Rio de Janeiro) (A FOLHA NOVA, 1884a, p. 3). In the same year, Sociedade Race Club was created in the Botafogo neighborhood, with the goal of organizing foot and bicycle races (the latter were predecessors of cycling, a modality that used to integrate athletics clubs' racing programs, celebrating the valorization of speed and other principles of progress9) (A FOLHA NOVA, 1884b, p. 1).

The practice soon spread to other parts of the city. In 1885, Clube Olímpico Riachuelense (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885, p. 1) and Clube Atlético Boca do Mato (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1884a, p. 2), located in the neighborhoods of Riachuelo and Engenho Novo, respectively, opened their doors in the northern region of the city, that was growing and becoming more heavily populated. Nearby, in the neighborhood of São Francisco Xavier, Clube Atlético Recreativo was created in 1886 (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1886a, p. 2). In 1887, Clube Atlético Leopoldinense was founded (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1887, p. 4). Clube Atlético Familiar was installed in a private owned turf located in Tijuca (O PAIZ, 1885b, p. 2), near Clube Atlético Andaraí Grande (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1886b, p. 2). Both are indicators of the greater occupation of that important area in the north region. Farther away, on the west side of the city, Clube Atlético Realengo was established (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1887, p. 5).

The growth in interest in the sport was also related to advancements in the urbanization process, the formation of middle classes and the improvement of public transport - the improvement of tram lines and installation of railways10. As the city spread, residents of the new neighborhoods became progressively interested in sports11. For these new areas, far from the sea and, at times, from horse racing tracks, the events held by athletics clubs were the first sports experiences, pioneers that promoted new uses of the body and a more soothing possibility of public exposure.

Besides clubs and associations, commercial sites dedicated to sport were also created, such as the Boat Rink, managed by Saul Severino in a new neighborhood called Vila Guarani. The venue could be rented by people interested in promoting competitions12 and promoted its own tournaments, profiting with revenues from the sale of tickets and betting. The establishment eventually attracted a considerable crowd and became popular in the city, but it was soon replaced by a horse racing track, called Prado Guarani (CHEVITARESE, MELO, 2018).

Other establishments had similar formats, but hosted exclusively Brazilian runners: Foot Rink (founded in 1884) and Club Rink (created in 1885) (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1886a, p. 1), both located in the neighborhood of Estácio, a not-so-noble region in the city. There was also the Sport Club, housed in the Politeama Theatre, located in Rua do Lavradio, in downtown Rio de Janeiro (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1886b, p. 4). All of them held betting and recorded fights due to controversies or distrust in the results, known as “tribofes”. Foot Rink was eventually destroyed by the mob's fury (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885b, p. 2).

It is then not surprising that such business arrangements were contested by some leaders of British clubs (A FOLHA NOVA, 1885, p. 1)13. The discussion was about what should be considered an appropriate use of “athletic sports”. If some people desired to get involved with the sport, they should follow certain dictates, so it would not be mistaken for games of chance. It was a debate about the good uses of the body in the public scene, something that, as we have seen, was heavily publicized by medical and pedagogical discourses.

In fact, these initiatives did not defend the ideals of athletics (which associated physical and moral traits with educational intentions), but rather served a society with growing appreciation of public entertainment and constantly searched for novelties. That is why its importance in popularizing the sport should not be overlooked.

They exposed the hybrid feature of a sport that balanced between the sheer assemblage of spectacles and speeches emphasizing its educational nature. Two formats of the practice coexisted, explaining tensions that have always surfaced the fields of sports and entertainment in general, to a greater or lesser extent. It was more than just a connection to determined speeches, but a matter of the limits of excitement and behavior in the urban sphere.

These arrangements were made explicit when, in 1885, the club that would become the most important athletic society of the time emerged: Clube Atlético Fluminense.

Clube Atlético Fluminense (1885-1887)

In September 1884, newspaper advertisements invited anyone interested in participating as shareholder/associate in the creation of Clube Atlético Fluminense. During those final months of the year, it is possible to notice the structuring actions of the association, including the making of statutes, the election of the first board and the construction of the headquarters, located at the confluence of the streets Conde de Bonfim and Haddock Lobo, close to the Largo da Segunda-Feira, in Tijuca.

The site was a former farm acquired from Pompeu Augusto Cesar da Costa, commander who owned a coffee plantation, crop that used to be common in the neighborhood that was changing its profile, abandoning its rural features. Tijuca was going through a modernization process and the new association was an indicator of it. It is important to notice that during the second half of the 19th century, factories and hotels were gradually more common in the neighborhood, taking advantage of the abundance of water. As a result, a public transport structure was also installed.

The headquarters was planned to host not only racing competitions (with a 300 by 8 meter track), but also shooting, skating, fencing, gymnastics, among others (A FOLHA NOVA, 1884c, p. 1). This is an important differential feature: the multisport character of the association. The diligence in preparing the facilities was often followed in details by the press, which, from its early moments, filled the initiative with laurels. The venue could receive around 2000 people, offering diverse facilities, although, at times, the chroniclers suggested a much larger audience.

If, on the one hand, Clube Atlético Fluminense had associated members, on the other hand it also manifested the intention to attract audience by charging admission. To this end, several strategies were developed. Inaugurated with a big party, in July 1885, counting with the presence of the Imperial family and important members of the city, the venue stood out for being open daily and offering an intense and varied program.

Frequently, the association was praised for its dynamics: “Clube Atlético has managed to stand out since the day of its inauguration, not only for its good management but also for the way in which it seeks to carry out its intended purposes, and the result can be seen in the reception that it has found in the public” (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885c, p. 1)14. Due to the variety and regularity of its events, the issue regarding the uses of the body in public was made even more explicit there than in other cases.

The runners, who practiced daily, replicated the habits of rowers, characters who were not yet notorious, but were already on the way to becoming distinguished for their lifestyle and body shape, something that would be more evident in the final decade of the century (MELO, 2001). Where there was no sea, there were athletics clubs. In both cases, bodies were exhibited in increasingly appreciated performances.

Although the club was farther away from the central and southern regions of the city, it attracted people who lived in those areas. A chronicler observed that the number of trams arriving in Tijuca on the days of events was rather large (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885d, p. 1). On these occasions, the city tram company (Companhia de São Cristóvão) used to increase the number of vehicles on the lines that served the neighborhood, and also offered extra direct lines from Largo de São Francisco, following a plan by Paulo de Frontin, who was already involved with sports and at the time led the creation of the Derby Club.

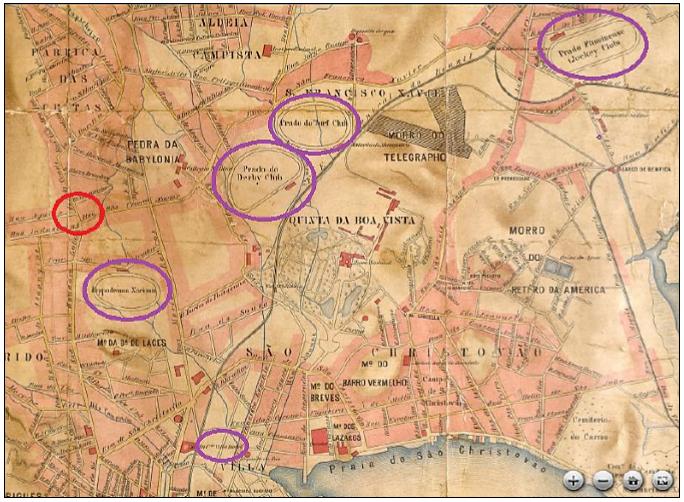

It is worth noting that not only the city started to throb in a region that not very long before was essentially rural, but people from other areas of the capital also traveled to attend the events promoted there. In fact, the association anticipated and integrated the entertainment scenery that would be provided by four horse racetracks that were installed in its vicinity in the latter half of the 1880s. Prado Fluminense had already been functioning since 1849, but it became more active in the 1870s (MELO, 2001).

Source: Luso-Brazilian Digital Library. Available at https://bdlb.bn.gov.br/acervo/handle/20.500.12156.3/27205. Accessed on Aug 18. 2020.

Figure 1 Map of the city of Rio de Janeiro and suburbs, Ulrik Greiner, 190? In lilac, the five horse racetracks of the city. In red, the area of Clube Atlético Fluminense.

The public repercussion of Clube Atlético Fluminense was recognized by Artur Azevedo, an author, journalist and playwright who was always attentive to what was happening in the city, and who used to mobilize sports to engage in social criticism (KNIJNIK, MELO, 2015). Azevedo inserted a reference to the association in one of his magazine pieces, O Bilontra, from 1885, where he compared it with Derby Clube. The characters suggested a difference between the ends of the two societies (assuming that part of the audience actually preferred horse races):

1st SPORTSMAN - Nevermind! It is the most beautiful of the race tracks!

2nd SPORTSMAN - I prefer Clube Atlético Fluminense, which also opened this year.

1st SPORTSMAN - For Goodeness sake, Mr. Xavier, don't you mix things up. A Club is a club, and a race track is a race track.

2nd SPORTSMAN - I know that; it’s no news for me.

1st SPORTSMAN - And as far as races are concerned, I want the ones with animals. This thing with tailless donkeys is not for me.

This dialogue shows once again the two dimensions that surrounded sport. The horse races were just pure entertainment, and little concern on health and hygiene was associated to them. Foot racing, jumping and throwing competitions, however, could be considered less exciting, as they were not as fast, but they more intensely dramatized the possibilities of using the body based on certain principles.

Such aspect was made clear when the club promoted one of the events that contributed to the popularization of the sport: Bargossi and his wife, internationally renowned European runners, were received in a grand celebration and ceremony, to compete in races and demonstrate their speed and endurance skills (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885c, p. 1).15 The athletes, who were received by the emperor, also performed in other areas of the city. The repercussions of these exhibitions were recorded for years in the newspapers. As one chronicler suggested: “Now that Bargossi is here, everyone wants to show that if they don't have a pair of legs like his, they at least try to rival those of the famous wanderer” (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885e, p. 1).

The runner also called the attention of Artur Azevedo, who dedicated some chronicles to the “wanderer of the wanderers” (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885f, p. 1). As the author stated, always with a pinch of irony:

He is a magnificent type of the strong human race. Cheerful, alive, intelligent, healthy. He gesticulates like a provincial actor and speaks through the guts of Judas… He has been walking pedibus calcante all over Europe, and it will be no wonder that one day he will do the very same thing that Vasques has so often done for mockery: a trip around the world on foot. (…). A man who runs so much must really be an object of admiration in a country that is walking so slowly. Bargossi's legs have iron muscles (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885f, p. 1).

Bargossi was called the “locomotive-man”, an explicit metaphor for the modern representations that surrounded him. The newspaper Diário de Notícias portrayed him in their pages informally dressed, with a challenging stance, exhibiting a proud masculinity16.

On the same occasion, the first prominent Brazilian runner appeared, Germano de Almeida, a challenger for Bargossi. A pioneer of “heroes” who received great attention and praise from the press and were acclaimed as examples for the youth, role models for the adoption of the habit of exercising (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885b, p. 1)17. If the public spectacle worked as an education of the senses when presenting other possibilities for the use of the body, these “sportsmen” were represented as carriers of the message of a new time, whose challenge was to reach the same level as the so-called more civilized societies.

In fact, it is worth noting that the newspapers often registered the large number of people enrolled in the races. At Clube Atlético, there were around 300 per competition at times, including many women, who occupied a constant and important space in the races18. Furthermore, over time, they adopted a format that is closer to what we have today in athletics competitions.

Many chroniclers began to record the forging of the new habit: “So what? Is the taste for racing developed or not?” (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885f, p. 1). Even considering that such a position could be marked by optimism from those who supported the development of sports, the contributions of athletics clubs to the popularization of the sport should not be neglected.

The profile of the managers of Clube Atlético Fluminense was an expression of the group that was involved. Two presidents took over in the first term. Antonio Pereira de Araujo Bessa was a Mason and businessman linked to a small enterprise, Companhia Industrial de Encaixotamentos, while José Coelho Barbosa was the owner of a homeopathic pharmacy and a member of the Hahnemannian Institute. Important traders served as secretaries, João de Azevedo Fernandes Guimarães and Jacintho Pinto de Lima Junior (future president of the Clube de Regatas do Flamengo).

Like the directors, the associates were part of the middle class, living in the vicinity of Tijuca or the city center, involved in professions connected to the city's “progress”, as engineers, military, doctors, pharmacists and small entrepreneurs. It is not surprising, therefore, that the sport was interpreted for utilitarian purposes: utile Dulce, a dimension that has always marked the development of the sports field (MELO, 2014). According to these speeches, people should not encourage any sort of entertainment, but only those that could bring some symbolic and material gain to society and the nation.

One example of this connection is the fact that the board often programmed races for children and young people, always announcing intentions to contribute to the education of the youth through a civilized and healthy experience. That is a reason why the existence of betting, to a certain extent, was overlooked by critics, since the profits were invested in improving the facilities of the association.

For a chronicler, in order to avoid having to resort to betting as a means for maintenance, athletics clubs should receive government funding, since they allegedly encouraged important habits for citizens who should be ready to protect the nation (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885a, p. 2), a concern that had grown as a result of the Paraguayan War (SILVA, MELO, 2011). Racing was, in his opinion, a good tool for military training. For that reason, some defenders of the sport preferred endurance to speed races (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885h, p. 1).

There were also suggestions regarding how the sport could be beneficial to people’s health, due to the development of "the strength of the motion organs and the increment of the capacity of the lungs" (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885i, p. 1). This was still, in fact, little understood at the time. It may be seen as another indicator of the influence of medical thinking on the application and encouragement of the new uses of the body.

The main point, however, was the potential contribution of a civilized experience to social development. As suggested by Sportman, a chronicler specialized in the theme, “everything that is elegant in the high life of Rio de Janeiro can be found there, as in a joyful meeting” (GAZETA DA TARDE, 1885, p. 2)19.

It was an experienced marked by little formality, with more comfort than luxury, that moved elite visitors, especially women, to look for the most appropriate outfits. The newspapers stressed this need to dress accordingly for athletics events, taking into account the new public spirit. If new uses of the body were on the scene, the procedures and limits of these new occasions had to be explained.

Progress, an idea so widely used in the actions of the association, did not admit the old exhibitions of very heavy outfits. Nor should they be too short. There was a new idea of elegance to be sought, in another indication of body regulation. It was a forum for negotiations in the context of cultural and economic changes - new habits and new products weighed in the debate regarding the constitution of a renewed possibility of dressing20.

Demonstrating their progressive spirit, the board of Clube Atlético took other measures. For example, the club contributed with social aid initiatives, including those related to the liberation of slaves, joining other associations in the entertainment field that were engaged in the cause (MELO, PERES, 2014). At the same time, they never neglected the public, introducing diverse activities to make their programs more attractive, usually offering competitions or exhibitions of different modalities, in addition to their restaurant and the beautiful gardens, in which there were constantly musical performances.

Clube Atlético Fluminense quickly became part of the sporting scenery in Rio de Janeiro. A rowing team competed in races promoted by the Clube de Regatas Guanabarense. Gymnastics classes and a partnership with Clube Ginástico Português were instituted. It became the main skating space after the old Skating-Rink closed (MELO, 2017b). Several associations and schools used the club’s facilities to organize athletics events. It became a “physical education center”, a radiating point for the practice of physical exercising.

Despite its success, in 1887, the club ceased to exist. We don't know exactly why, but it is possible to infer something about the end of its trajectory. In the first half of that year, there seems to have been some discomfort in the board that interfered with the functioning of the association, difficulties in renewing and mobilizing members (GAZETA DA TARDE, 1887a, p. 2). In July, a provisional commission tried to recover the previous dynamic (O PAIZ, 1887a, p. 2). That month, they managed to promote an event, apparently with the usual success (GAZETA DA TARDE, 1887b, p. 2). In September, the facilities were used in an activity of the German School. In October, it became clear that the efforts did not seem to have been successful with the establishment of a liquidating commission (O PAIZ, 1887b, p. 2). Soon the auction of the club’s assets and the land of the headquarters was announced (O PAIZ, 1887c, p. 2).

In fact, in the transition from the 1880s to the 1890s, there were several problems that surrounded athletics associations. Perhaps even the excessive number of activities contributed to its decline. Rio de Janeiro’s society increasingly valued novelties. Moreover, it was not easy to make the initiatives financially viable. Betting was always an important element for this. However, at that time, a number of debates took place around its prohibition.

In addition to the aggravation of the British with the damage to sport’s educational character, the Ministry of the Empire, chief of police Costa Ferraz, and José do Patrocínio, as councilor, proposed attitudes to restrict and regulate betting, triggering a major public debate21. In general, this had greater effect on horse racing clubs, but rowing and athletics events also felt its impact, also due to the establishment of taxes and the suspension of bets, which troubled their maintenance mechanisms. Furthermore, the House of Representatives banned sports activities between December and April, apparently due to health concerns in the summer (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1887l, p. 1).

In Niterói, the clubs Olímpico Guanabarense and Atlético Brasileiro also closed their doors, in 1887 and 1888, respectively (MELO, 2019b). In the nation’s capital, Rio Cricket still promoted its events until 1889 (THE RIO NEWS, 1889, p. 2), but it faced a strong identity crisis, accentuated by the proclamation of the Republic, that had direct impacts in its functioning (MELO, 2017a). The British Club, likewise, did not resist and closed down. In Rio de Janeiro, all the above-mentioned associations were extinguished, but others were created.

In 1889, the clubs Oito de Setembro and Olímpico Fluminense, the latter in the São Cristóvão neighborhood, promoted races. In that same year, Clube Esportivo Nove de Julho was created in Sampaio. In 1890, Clube Campesino organized events in the neighborhood of Riachuelo. In a region farther from the city center, Clube Atlético de Irajá (based in Madureira) and another Clube Atlético Brasileiro (in Cascadura) were founded. The sport continued to be structured in the areas farthest from the central region.

It is also worth mentioning Clube Atlético Guanabarense, dedicated to foot racing and cycling, founded in 1889, in the Botafogo neighborhood, taking advantage of a public excitement already forged with the regattas since the mid-19th century, especially with the initiatives of Clube de Regatas Guanabarense and Clube Guanabarense.

Popularity may not have been the same, but it is safe to say that the continued creation of athletics clubs demonstrates that a taste for the sport was established in the population of Rio de Janeiro, something that would become exponential and gain other formats in the following decades.

Conclusion

“Athletic sports”, the beginning of athletics, were spreading in Rio de Janeiro during the 1870s and 1880s, passing from a modality eminently valued by English speakers, pioneers in structuring initiatives, to a sport that drew assistances and that was later practiced also by Brazilians, who in turn gave it their own connotation, sometimes clashing with the British colony vision.

The popularization of the sport was a result of a dynamic in which a more intensely developed entertainment market was articulated with the process of adhesion to the ideas and imaginary of modernity, with greater affiliation to notions of civilization and progress.

In addition to cultural exchanges, related to the influence of foreigners, the creation of athletics associations was also an expression and indicator of the growth of the urban area of the city, and the need to expand the area of residence for people from middle strata who became better defined according to socio-economic changes. It should be considered that the fact that associations dedicated to “athletic sports” needed less investment in structure than horse racing and nautical ones made it easier for them to appear.

The sport was a link between the moment when sports were mostly conceived as a spectacle and another in which a moral base linked to medical and pedagogical discourses also developed more effectively. It is not uncommon, therefore, that some actions of athletics clubs overlapped with other initiatives in the sports or gymnastics field, to the same extent that there were experiences that adopted an eminently entrepreneurial structure.

In this scenario, it was possible to notice the tensions surrounding sports, related to the good uses of the body and the city. Clube Atlético Fluminense managed to articulate the two dimensions under debate, adopting the dynamics of spectacles, but also initiatives and speeches that highlighted the concerns with education, health and hygiene. As a result, it achieved great acceptance and social respectability. Despite its short existence, it made great contributions to the spread of the sport and the conformation of sport in general in Rio de Janeiro. And also regarding a process of education of the body, as we tried to demonstrate.

Athletic sports did a good job in presenting new uses of the body in the public scene, something that involved competitors showing a new muscular complexion, but also the public learning how to dress and behave in the stands. The limits of these behaviors were established in the tension between the pure marketing of the show and the dictates of medical and pedagogical order. It was clearly a process of educating the body.

In the future, it will be worth investigating the experiences of athletics clubs at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when the speeches relating sport to health and hygiene parameters were already more consolidated, as well as a morality standard that definitely condemned betting and elected athletes as important social role models.

REFERENCES

A FOLHA Nova, Rio de Janeiro, 20 out. 1884b. [ Links ]

A FOLHA Nova, Rio de Janeiro, 25 mar. 1885. [ Links ]

A FOLHA Nova, Rio de Janeiro, 29 jun. 1884a. [ Links ]

A FOLHA Nova, Rio de Janeiro, 3 dez. 1884c [ Links ]

ASSUNÇÃO, Beatriz Albarez de; ITALIANO, Isabel Cristina. Moda e vestuário nos periódicos femininos brasileiros do século XIX. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, São Paulo, n.71, p.232-251, dez. 2018. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v0i71p232-251 [ Links ]

BRASIL, Eric; NASCIMENTO, Leonardo Fernandes. História digital: reflexões a partir da Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira e do uso de CAQDAS na reelaboração da pesquisa histórica. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 33, n. 69, p. 196-219, jan.-abr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/s2178-14942020000100011 [ Links ]

CANCLINI, Néstor García. Culturas híbridas: estratégias para entrar e sair da modernidade. São Paulo: Edusp, 1997. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, José Murilo. A vida política. In: CARVALHO, José Murilo (coord.). História do Brasil Nação (1808-2010) - volume 2 - A construção nacional (1830-1889). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2012. p. 83-130. [ Links ]

CHEVITARESE, André Leonardo; MELO, Victor Andrade de. Embates na sociedade fluminense: a experiência do Prado Guarany (1884-1890). Revista Brasileira de História, São Paulo, v.38, n.78, p.235-258, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-93472018v38n78-11 [ Links ]

CLARK, T. J. A pintura da vida moderna. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

CORBIN, Alain (org.). História dos tempos livres. Lisboa: Teorema, 2001. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro 22 mar. 1887l. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 1 jul. 1886a. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 10 ago. 1885c. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 12 ago. 1885a. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 14 ago. 1885e. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 16 out. 1885g. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 2 fev. 1886b. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 20 ago. 1887. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 23 ago. 1885h. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 24 abr. 1887k. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 24 ago. 1885b. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 26 fev. 1887j. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 27 jul. 1885d. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 3 dez. 1885i. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 31 jul. 1885f. [ Links ]

FAURE, Olivier. O olhar dos médicos. In: CORBIN, Alain; COURTINE, Jean-Jacques; VIGARELLO, Georges (orgs.). História do corpo. Da Revolução à Grande Guerra. Volume II. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 2008. p. 13-55. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Nelson da Nobrega. O rapto ideológico da categoria subúrbio. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 1995. [ Links ]

GAZETA da Tarde, Rio de Janeiro, 10 ago. 1885. [ Links ]

GAZETA da Tarde, Rio de Janeiro, 11 jul. 1887b. [ Links ]

GAZETA da Tarde, Rio de Janeiro, 7 set. 1887a. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 10 ago. 1885b. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 12 jun. 1887. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 12 nov. 1884c. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 19 out. 1884b. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 21 mai. 1886a. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 21 nov. 1884a. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 28 abr. 1885. [ Links ]

GAZETA de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 8 mai. 1886b. [ Links ]

GUNNING, Tom. O retrato do corpo humano: a fotografia, os detetives e os primórdios do cinema. In: CHARNEY, Leo; SCHWARTZ, Vanessa (orgs.). O cinema e a invenção da vida moderna. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify Edições, 2001. p. 39-80. [ Links ]

HOLT, Richard. Sport and the British: a modern history. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

JORNAL do Comércio, Rio de Janeiro, 4 ago. 1884. [ Links ]

KNIJNIK, Jorge; MELO, Victor Andrade de. Uma nova e moderna sociedade? O esporte no teatro de Arthur Azevedo. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, Florianópolis, v. 37, n. 1, p. 11-19, jan.-mar. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2012.05.001 [ Links ]

LUCA, Tânia Regina. História dos, nos e por meio dos periódicos. In: PINSKY, Carla B. (org.). Fontes históricas. São Paulo: Ed. Contexto, 2005. p. 111-153. [ Links ]

MAIA, João Marcelo E. Costa Pinto em dois tempos: os efeitos periféricos na circulação de ideias. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 31, n. 2, p. 173-198, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2019.148331 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. “Pois temos touros?”: as touradas no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX (1840-1852). Análise Social, Lisboa, v. 50, p. 382-404, 2015a. [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. A sociabilidade britânica no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX: os clubes de cricket. Almanack, Guarulhos, v.16, p.168-205, 2017a. https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320171604 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Antes do club: as primeiras experiências esportivas na capital do império (1825-1851). Projeto História, São Paulo, v. 49, p. 1-40, 2014. [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Cidade Sportiva: primórdios do esporte no Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará/Faperj, 2001. [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Enfrentando os desafios do mar: a natação no Rio de Janeiro do Século XIX (anos 1850-1890). Revista de História, São Paulo, n.172, p.299-334, jan.-jun., 2015c. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2015.98755 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Esporte e lazer: conceitos - uma introdução histórica. Rio de Janeiro: Apicuri/Faperj, 2010. [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Experiências de ensino da dança em cenários não escolares no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX (décadas de 1820-1850). Movimento, Porto Alegre, v.22, n.2, p.497-508, 2016. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.56852 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. O espetáculo que educa o corpo: clubes atléticos na cidade de Niterói dos anos 1880. História da Educação, Pelotas, v. 23, e85836, p. 1-34, 2019b. https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/85836 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. O sport em transição: Rio de Janeiro, 1851-1866. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 21, n. 2, p. 363-376, 2015b. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.49489 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Trânsitos culturais: as experiências dos primeiros clubes athleticos do Rio de Janeiro (1873-1883). Movimento, Porto Alegre, p. e25098, dez. 2019a. Disponível em: <https://seer.ufrgs.br/Movimento/article/view/90653>. Acesso em: 11 fev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.90653 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de. Uma diversão civilizada - a patinação no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX (1872-1892). Locus, Juiz de Fora, v.23, n.1, p.81-100, 2017b. https://doi.org/10.34019/2594-8296.2017.v23.20843 [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade de; PERES, Fabio de Faria. A gymnastica no tempo do Império. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2014. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 10 jul. 1887a. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 16 out. 1887b. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 18 nov. 1885a. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 20 dez. 1886. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 24 mai. 1885c. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 26 out. 1887c. [ Links ]

O PAIZ, Rio de Janeiro, 27 set. 1885b. [ Links ]

PERES, Fabio de Faria; MELO, Victor Andrade de. O corpo da nação: posicionamentos governamentais sobre a educação física no Brasil monárquico. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.21, n.4, p.1131-1149, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702014000400004 [ Links ]

POPINIGIS, Fabiane. Proletários de casaca. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 2007. [ Links ]

PORTER, Roy. Os ingleses e o lazer. In: CORBIN, Alain (org.). História dos tempos livres. Lisboa: Teorema, 2001. p. 19-58. [ Links ]

SCHETINO, André Maia. Pedalando na modernidade: a bicicleta e o ciclismo: uma análise comparada entre Rio de Janeiro e Paris na transição dos séculos XIX e XX. Rio de Janeiro: Apicuri, 2009. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. As barbas do Imperador. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

SILVA, Carlos Leonardo Bahiense; MELO, Victor Andrade de. Fabricando o soldado, forjando o cidadão: o Dr. Eduardo Augusto Pereira de Abreu, a Guerra do Paraguai e a educação física no Brasil. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.18, n.2, p.337-354, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702011000200005 [ Links ]

SOARES, Carmen Lúcia. Corpo, Conhecimento e Educação: notas esparsas. In: SOARES, Carmen Lúcia (org.). Corpo e História. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2001. p. 109-129. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Gilda Mello e. O espírito das roupas: a moda no século XIX. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1987. [ Links ]

THE RIO News, Rio de Janeiro 26 ago. 1889b. [ Links ]

THE RIO News, Rio de Janeiro, 14 jan. 1889a. [ Links ]

2When discussing these paradoxes, Porter is referring to the fact that industrial society stablishes a strong rhythm of labor in consonance with an increasingly intensive entertainment market. A dubious message is then emitted: one must work hard, but also play hard. This scenario sets the tone for an activism that eventually ends up disqualifying the “unoccupied time”. It is, therefore, a symbolic and material construct that reinforces the interests of industrial society. That is why I rather approach it as an ambiguity than a paradox.

3This should not be seen as a traditional center-periphery relationship, in which people in Brazil would have copied exactly what happened in Europe. It is aligned with authors who perceive that there are asymmetries and cultural traffic flows. Noticing, nevertheless, the reinterpretations and reframings of such processes. For a debate on the topic, see Maia (2019). See also Canclini (1997).

4The journals were accessed through the National Library’s digital newspaper section, called Hemeroteca Digital. About the advantages, limitations and precautions to be taken when using this resource, see Brasil and Nascimento (2020)

6This journal published information that was considered relevant to English speakers, including every day news, among which those of sporting events.

8O Paiz was a major newspaper in Rio de Janeiro. It stood out due to its active participation in the abolitionist and Republican campaigns. Important chroniclers of the time wrote for the newspaper, many of them were eager to see the progress of society in Rio de Janeiro.

11Other associations appeared outside the capital city, in the province of Rio de Janeiro. In 1884, Clube Atlético Campista was founded in the northern region (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1884b, p. 4). In the southern region, Clube Atlético Vassourense (DIÁRIO DE NOTÍCIAS, 1885a, p. 2) was created in 1885 and Clube Atlético de Barra do Piraí in 1886 (O PAIZ, 1886, p. 2).

12The Fenianos club, for example, organized events at the venue (GAZETA DE NOTÍCIAS, 1884c, p. 3), as did a local gymnastics club, Congresso Ginástico Português (O PAIZ, 1885c, p. 2).

13This journal achieved certain notoriety at the time, but due to financial troubles joined the journal Brazil and originated the Diário de Notícias.

15Achilles Bargossi was born on April 22, 1847, in the city of Forlí, Italy. He was a common character from the 19th century, who used certain set of skills to earn a living by performing in spaces that were becoming more common with the expansion of the entertainment market. It was a moment of transition between the circus and sports exhibitions, in the modern sense (MELO, PERES, 2014). He exhibited his skills in many countries in Europe and in the Amercias (something that was only possible because the means of transport had been significantly improved, especially, in this case, the efficiency of steamships).

16Fabio Peres reflected on this topic in the blog História(s) do Sport. See https://historiadoesporte.wordpress.com/2014/08/24/mercado-de-entretenimento-saude-e-praticas-corporais-no-seculo-xix-a-historia-do-artista-atleta-bargossi-e-de-sua-familia-no-rio-de-janeiro-parte-1/>. Accessed on: 11 Feb. 2020.

17Gazeta de Notícias was one of the most important and influent newspapers in Rio de Janeiro in the 19th century. Many important chroniclers worked there, with critical gaze to Rio de Janeiro’s society.

18It is not our goal do discuss women’s participation in this article. It is nevertheless relevant to notice that “athletic sports” were important to promote the presence and importance of women in the public scene.

19Directed by José do Patrocínio, this newspaper was marked by its abolitionist feature and its attention to minority groups in the city.

Received: November 08, 2019; Accepted: February 09, 2020

texto em

texto em