Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.20 Uberlândia 2021 Epub Jan 29, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v20-2021-45

Dossier - Traces that leave traces: personal archives and present time

Teachers’ personal archives: what do they keep and what do they tell us?1

1Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil). libanianacif@gmail.com

2Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil). michellerobert@gmail.com

The article refers to the Personal Archive of Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino (1929-2013): teacher of history on university-admission preparatory courses in the south region of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and active intellectual mediator, having worked in radio programs; unions and entities aiming to defend political rights during the military regime. The text is divided into four sections: the first reflects on the nature of the personal files of K12 teachers; the second describes the contents of Aquino’s archive; the third articulates the holder’s personal characteristics with the marks of a professional culture of high school history teachers; the fourth and last section points to the evidence and challenges that emerged in the research, woven into the dialogue between the archival organization and the research activities with these documentary sources.

Keywords: Personal archives; Basic education teachers; History of the teaching profession

O artigo se remete ao Arquivo Pessoal do Professor Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino (1929-2013): professor de história de cursinhos pré-vestibulares da zona sul da cidade do Rio de Janeiro e ativo mediador intelectual, tendo atuado em programas de rádio; sindicatos e entidades dedicadas à luta em defesa dos direitos políticos, durante o regime militar. Está dividido em quatro seções: a primeira reflete sobre a natureza dos arquivos pessoais de professores da educação básica; a segunda descreve o conteúdo do Arquivo em questão; a terceira articula as características pessoais de seu detentor com as marcas próprias de uma cultura profissional atinente aos professores de história do ensino médio; a quarta e última seção aponta os indícios e desafios que emergiram nas pesquisas que foram tecidas no diálogo entre a organização arquivística e as atividades de pesquisa com essas fontes documentais.

Palavras-chave: Arquivos pessoais; Professores da educação básica; História da profissão docente

El artículo hace referencia al Archivo Personal del Profesor Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino (1929-2013): profesor de historia de los cursos de ingreso preuniversitario en la zona sur de la ciudad de Río de Janeiro y mediador intelectual activo, habiendo trabajado en programas de radio; sindicatos y entidades dedicadas a la lucha por la defensa de los derechos políticos durante el régimen militar. Se divide en cuatro apartados: el primero reflexiona sobre la naturaleza de los archivos personales de los docentes de educación básica; el segundo describe el contenido del Archivo en cuestión; el tercero articula las características personales de su titular con las marcas de una cultura profesional relacionada con los profesores de historia de secundaria; la cuarta y última sección apunta a las evidencias y desafíos que surgieron en la investigación que se entretejieron en el diálogo entre la organización archivística y las actividades de investigación con estas fuentes documentales.

Palabras clave: Archivos personales; Profesores de educación básica; Historia de la profesión docente

Teachers’ personal archive: what do they keep and what do they tell us?

The article analyzes the Arquivo Pessoal do Professor Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino (1929-2013) [Personal Archive of Teacher Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino]. Aquino was a history teacher on preparatory courses for university admission in the south region on the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Though working full time as a teacher, he has also participated in several spaces of intellectual mediation, such as radio programs; cultural activities in unions; participation in entities that defended the rights of the families of those dead or who disappeared during the military regime, such as Amnesty International and the group Tortura Nunca Mais [Torture Never Again]. Besides this, he had two passions: the soccer team Flamengo and the Rio Carnival Samba School called Mangueira. Throughout his life, he accumulated a vast number of documents that assemble a variety of records, considering the multiple activities he developed. However, in this article, we will only deal with the documents referring to the pedagogical part of his Archive.

Receiving the personal Archive of a history teacher, who was a reference for a generation of teachers acting in K-12 education in Rio de Janeiro has given us the opportunity to follow a unique trajectory, as we can see in the evidences kept in the Archive. However, if the analysis of the documents allow us to observe the individual history of its owner, it also reveals some constraints, expectations, and hopes for a democratic society, articulating his work with this fight. It is worth highlighting that the didactic books he wrote have marked teachers’ and students’ trajectories who remember their impact, as they did not follow the standard of the books circulating in the 1980s and 90s. It has been common to hear testimonies of former students, many of whom tell us that the decision to become historians were, in a great measure, inspired by Aquino’s example.

After this initial introduction, we present the structure of the article which is divided into four sections: the first presents our point of view on the nature of personal archives of K-12 teachers; the second describes the content of Aquino’s archive; the third articulates the holder’s personal characteristics with its own characteristics of a professional culture of high school teachers; the forth and last section presents some evidences and challenges which emerged in the research done for the tenure thesis of one of authors and the masters’ dissertations of other author. The observations gathered here were drawn from the dialogue between the work of archival organization and the development of research activities on these sources.

1. Personal archives of K-12 teachers

We start this section stating that it is uncommon to find personal archives of K-12 teachers, institutionally organized and open to public research. On the other hand, we believe it is not uncommon to find archives organized by the teachers in their own houses. Both findings suggest some explanatory hypothesis. First, we should consider that teachers’ profession is established as a dissemination activity and the more democratic the access to school is in the country, the broader is its public. Such task demands a wide array of data and information, as well as the experimentation of different strategies to mediate scientific knowledge.

On the other hand, the profession of K-12 teacher is also an activity held by a great number of professionals that aim to establish a palatable communication for a large and heterogeneous audience, for most teachers composed of children and young people. Due to their work conditions, K-12 teachers deal with a tremendous fragmentation and expropriation of their time2, with a workday of multiple shifts and classes, often with different age groups. These also have diverse learning demands and contents, leading to dispersion and creating great professional challenges.

Thus, teachers develop a work of intellectual mediation that places them as disseminators of knowledge produced by others. We agree with Gomes and Hansen (2016), on the complexity and importance of works on cultural mediation, though we recognize the symbolic power of hierarchies surrounding the academic environment.

For these reasons, we believe that the preservation of the archives of K-12 teachers in safekeeping institutions3 is rare. On top of that, the fact that these intellectual mediators4 - teachers - do not have the available time to record their work and reflect on them. Therefore, they end up maintaining a certain invisibility on the relevance and complexity of the ways they produce and mediate knowledge, as well as the results of their works. Finally, we remember that the results of teachers’ work, as a rule, can only be mediated in the medium to long term, as they deal with human beings and visible and invisible factors may interfere in their work.

Summing up, we can say that as producers of a specific type of knowledge - school knowledge - these teachers create synthesis that articulate contents from different fields - in the case of our study, history and historiography; didactics and methods for history teaching; the political and the pedagogical debates; the theme contents of school curricula in different educational levels; knowledge on psychology and communication, among others. All these to make more attractive the contents to be taught, following the interest and the cognitive development of the school audience, adapting the intellectual mediation (what many call practical tasks) to the needs of the moment. It is worth highlighting that each student and each group have very particular characteristics and the good relationship between teacher and students requires fine-tuning, what demands a good measure of affection.

In this aspect, we must remember the advancements on the perception of the specificities of K-12 teachers’intellectual production, based on the studies of Maurice Tardiff (2010). The author shows that teachers’ knowledge are timeless, plural, heterogeneous, eclectic and syncretic, personalized and situated. Therefore, he offers us a positive interpretation - which avoids classifying teachers’ knowledge by what it is not, by the characteristics that it does not have when compared to scientific and academic knowledge, for example. This allows us to notice the documents preserved in the personal archives of K-12 teachers, considering their specificities and evaluating their value as the materialization of a complex, original, and creative work of intellectual mediation.

So, we conclude that the value attributed to the documents kept in the personal archive of a K-12 teacher requires a very specific interest. In our case, we wanted to understand what and how the teacher plays his/her role and fulfill his/her professional activity. To be interested in this work - one produced by so many other professionals in the same role - and also its production - so invisible, veiled by the rush to “make do” in time and answer to all and every demand - one needs to see its complexity and relevance, beyond appearances.

Our experience in exploring and organizing the documents of Aquino’s personal archive led us to think these questions from the artisanal way this teacher built his memory and his legacy. To Mills (2009) the personal archive of a social scientist (which we believe can be expanded to a teacher’s archive) expresses, above all, the way he/she sees him/herself as a professional and as a person.

Therefore, the documents kept by K-12 teachers tend to be an extremely personal archive and, at the same time, mundane. Personal because it assembles documents, texts, books, notes, class diaries, among other items that only interest them and keep useful information during a school year, becoming useless the next year.

On the other hand, the documents kept in the archives of these teachers can often seem extemporal. That is, they do not show precisely their times, except by the type of support used to produce them. In the case of the researched archive, there are many texts used in class, showing that a good text was used by many classes for many consecutive years, what explain the lack of headings and, sometimes, gluing the extracts of a new text, as well as topics of other syllabus to guide the explanations to be given in class. Such imprecisions, if we may say so, raised doubts in the team that organized the archive, as we will see in the following section which will deal on the composition and the issues emerged when describing the archived items.

2. The pedagogical archive

The pedagogical part of teacher Aquino’s archive was received5 on April 20th, 2017. We immediately started the organization of those documents, gathering the folders that assembled the documents used in the schools he worked. On this, it is important to highlight how fruitful was the effort to find a category that would best describe each item to register the catalogue of documents in the Archive. Following the Brazilian rule of archival description, a team of undergraduate researchers, under our coordination and the supervision of the archivist of the institution6 identified and grouped the documents, creating a preliminary catalogue. After that, we started the processes of adequate hygiene and safekeeping of the books on his pedagogical library for a later register.

Luciana Heymann (1997) highlights the tensions that permeate the constitution of a private archive, emphasizing the selection done by its holder, who keeps or throws away these ‘residues’ according to the memory that will best mirror the identity marks he/she values. Besides the interference of the holder when composing the archive, the author reminds other following interventions, especially after the holder’s death. Some interventions are done by part of the family, which reorganizes the documents depending on the space and the ways to safekeep them; others by the safekeeping institutions that, when receiving the archive, submit them to the required technical rules.

In fact, as we have highlighted, the collection of documents we focus on this article is a small part of a much larger and diversified document set. In this pedagogical section, we have found the books he wrote; materials gathered to write his books and prepare classes, especially illustrations, maps, and cartoons; some institutional letters, and many lesson plans, summaries, booklets from the different schools he worked; comments on films; themed dossiers, among other items. The documents have arrived with the organization established by the author and later readjusted by his heirs, with the aid of a family friend, who is a professional in the area of history and librianship7. This previous organization has helped the access and the handling of the items, respecting, whenever possible, the holder’s organization.

The size of the archive led his inheritors to fragment the document set, to facilitate its distribution through different safekeeping institutions8. This shows another characteristic: its variety. Though we have worked with just a part of the broad set of documents, it was possible to notice a clear articulation and integration of the records in different actions and the ambitions drawn by the holders’ trajectory. Knowing the content of the other parts of the set has certainly contributed to this perspective. On this, it is worth highlighting the importance of other Documentation Centers to promote a broader dissemination on the location of parts of the archive under their keep, allowing researchers to promote an integrated interpretation of the evidences that compose the totality of the Archive left by the holder.

During the work of document organization, it was clear to the team how Aquino structured himself as a history teacher and performed the functions demanded by his job. The observation of some document sets allowed us to dialogue with the procedures he adopted aiming to prepare his lessons and communicate with the students. Regarding our research interest, the intention was to capture the particularities and the common ways to teach that emerged from reading this material.

There are abstracts, class plans, annotated summaries, lists of contents followed by newspaper clipping, among many other ways to organize the information to be taught to his students. These documents show that the teacher knew (from the examples given by Aquino) how to turn extremely complex contents into something understandable to students. The class plans were repeated in different reproduction supports (mimeographed, typed, printed in inkjet, in laser jet, etc.). This shows that, when establishing his archive, Aquino lived a moment of technological transition in which digital supports started to appear, showing some hybridism on the archived material.

As we have signalized, these repetitions in the class plans - encompassing an articulated list of events that marked the historic processes studied - shows the great number of classes he taught, the amount of students that, some courses with 200 students in the classroom, as his own testimony9

In this sense, the characteristics pointed out show a type of modus operandi of the work of intellectual mediation developed, highlighting its complexity. As observed by Gomes and Hansen (2016, p. 32-33):

the mediators’ work, even when understood as a simplification/didactization of codes, languages, and knowledge, is far from easy. The simplicity acquires an array of complex meanings, grounded on ideas of selection and careful choice; a depuration that specify the more important meanings that needs to be communicated, what demands competences and specific and specialized experiences.

However, at first sight, some documents seem to have little importance, as a good part of the files gathers everyday materials that were constantly replicated. For instance, leftovers of materials used in the classroom, thus, carrying the personal marks of the teachers who worked with them. Besides this, they can be outdated, as history, and the knowledge that explains it, are extremely dynamic.

Therefore, within an organization perception with no research goal, these documents could be historic garbage, that is, could have been discarded, because of its extremely informal format, as many class plans did not even have a data or a header to identify the institution it belonged. If historic garbage refers to every document that does not deserve to be kept, thus becoming a historic source, it is important to notice that, under the appearance of an object with no historic value, these plans potentialize many interferences of the team on the arts of teaching10. The debate around its importance and the option of discarding these materials allowed us to reflect on the multiple possibilities to describe them, dialoguing with archival organization.

In the pedagogical library,11 we have found books, based on dissertations and theses that analyzed the beautiful lies told by didactic books, as well as those proposing to unveil the ideologies behind them.12 On this, among the typed documents, there are some studies Aquino developed on the didactic books circulating, from his undergraduate degree until the 1990s/2000s.

We can thus conclude that the personal Archives of K-12 teachers, in general, and the Pedagogical Library of the Archive of teacher Aquino, in particular, might offer excellent contributions to the studies on the area of history of education and the curriculum, historic and history education, as well as the profession of teachers.

3. The Archive: marks of the holder and the profession

Other documents have allowed us to follow the process of creating didactic books, with the proofs and adjustments done in the process. We must register a set of illustrations and maps prepared to compose the didactic books he wrote, as well as the cartoons, and other types of illustrations that directly dialogue with his authorial production. The use of cartoons in didactic books is a very peculiar trademark of Aquino, considering the possibilities he saw in the articulation between texts, drawings, and humor. He probably imagined to be possible to use this mixture to break the prejudice students held against the memorization history- based on a succession of facts and dates- far from the experiences and the interests of children and teenagers to whom he taught.

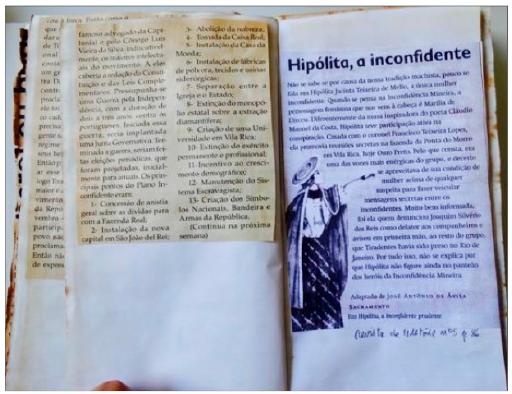

Thereby, he articulated different types of texts, documents, and illustrations, creating the conditions to allow historic subjects to be seen as human beings, same as the readers. These characters expressed the angst, ambitions, and doubts of common people who, in the end of the day, spoke about the historic context in which people lived. In the cartoon reproduced bellow, he personified Brazil - skinny and ruined by the institutionalized exploitation of the Colonial Pact. The later represented by the physician’s briefcase, who is well nourished and with Portuguese features

Source: Arquivo Aquino - Proedes / UFRJ.

Figure 1 Cartoon commissioned by Aquino to illustrate a didactic book he authored.13

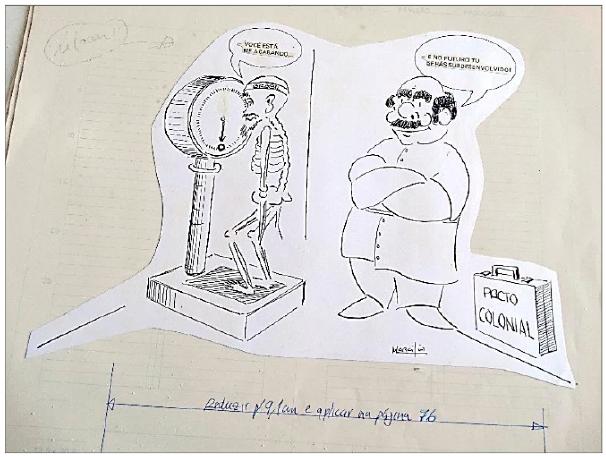

In the following cartoon, he created a curious dialogue between the clergy, the nobility, and the bourgeoisie to approach the Absolutism of Divine Right. He also takes the moment to approach the issue of censorship who, hidden in the shadows, is afraid of its role.

Source: Arquivo Aquino / Proedes - UFRJ.

Figure 2 Cartoon commissioned by Aquino to illustrate a didactic book he authored.14

Another aspect that can be seen as a personal characteristic on Aquino’s way to teach history, but that can also be perceived as a collective expression of the strategies of other K-12 history teachers, were the marks left in the books, with scribbles, newspaper clippings about the book or the topic approached. These evidences his interaction with the material, through reading/selecting/classifying/thoughts, and written marks. These marks left by the holder when interacting with the items archived, certainly indicate the paths to prepare the classes and the work of composing the texts that will be published, materializing themselves, in the class plans and compendiums he organized, as well as in his authorial work, such as booklets, didactic books, books on the themes of his preference - such as soccer and insurgent movements - and articles in collections.

The photos reproduced below are from a paradidactic book on the Conjuração Mineira, co-authored by Aquino. On the first page, we find a mark in red, correcting his own name, and, in the other pages, there are other review marks and the adding of new content through collages, such as a list with the claims of the insurgents and the information on Hipólita, the only woman in the group, probably unknown by the authors until the book was released.

On the other hand, the presence of songs and films, together with the pedagogical and historiographic material offer a perspective on the peculiar way Aquino composed his archive. Certainly, the news, songs, and movies he preserved were selected considering its didactic usefulness. Thus, we can suppose that these would be converted into tools to touch students through images, movement, and news on the individuals amidst the historical processes. When transformed into didactic material, these cultural products could also expand the focus of political history, which, traditionally, has been the organization axis of the subject curriculum, composing the contents required to college admission exams. Thus, he would keep the political focus strictusensu, but made an effort to call students attention to the habits, arts, affective relationships, and other subjective aspects of social life, reminding them that these aspects are always crossed by the processes and political events of their times.

As examples, the issue of culture and counterculture exemplified in the hippie movement of the 1960s-1970s, and the focus on other youth movements, such as May 1968 in France and the phenomenal success of the Beatles. Such themes are present in the documents selected by Aquino through news published in newspaper and magazines. This are part of his archive as cultural and political references widely known and recognized by its historical importance, but that would hardly be on the didactic books that circulated before or during his time as a teacher.

Considering other types of documents, beyond those directly used to compose the curriculum content of his booklets/books, we have found other items, such as poems, letters, magazine articles, supplements, maps, normally taken from printed materials from the a period of 30, 40, 50 years. Generally, the clippings are not ordered by dates but by themes. The article clippings are overlapped in different dates, updating debates, and given a continuity aspect to Aquino’s different readings, highlighting the dynamic aspect of his readings, which were in constant production15. Thus, we can point out the dialogic character - that is, relational and coherent- that these clipping represent in establishing the knowledge considered to be relevant by Aquino.

The effort to accumulate information resulted in a broad archive of knowledge that intended to be complete, closer to an encyclopedic knowledge. Such characteristic expresses a pressure exerted by the curriculum demand of university admission exams. The great demand for places in higher education and the insufficient offer, especially in the 1970s-1980s, created a great social pressure to broad the access to higher education, increasing the demands of the admission exams, so as to balanced the distribution of the few places available based on meritocratic individual criteria. In an articulated way, we believe that the broadening of knowledge demanded in the university admission exams has contributed to maintain a content-encyclopedic education that, still today, distinguishes the average level of the educational levels that make up K-12.

But the high school curriculum, in general, and the preparatory courses, in particular should be seen as the result of conceptions and shared action of specialized teachers that influenced the composition of curricula and tests to select the students considered to be apt to enter the universities, mainly public ones. In this aspect, two educational traditions complement each other and, - though criticized by the young teacher Aquino, cannot be dismissed by him, as this could disallow him as a specialist in his subject area and as a teacher, exactly at the final step of high school.

The first tradition refers to the teaching of the then- Faculdade Nacional de Filosofia (FNFi)16, before the University Reform of 1968. Still shaped by strict hierarchies between the professor and his/her aides, as well as the predominance of erudite, classic, and universal knowledge. The education of the historian in the FNFi demanded from its professors and students the mastery of broad types of knowledge. The second tradition comes from the characteristic that has historically defined high school as a mark of the elite education, those who would have access to higher education and the higher job positions. In this sense, the history curriculum in high school also had marks of erudition and a Eurocentric perspective of history. In the next section, we will approach some evidences and challenges on the work on organizing and researching the Archive.

4. The Archive: evidences and challenges

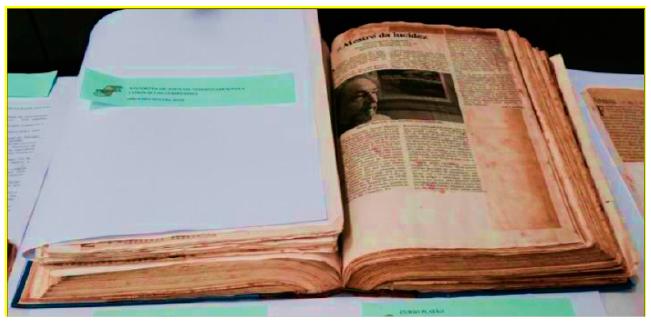

In the part named Pedagogical Library, the collection of different supports dedicated to the study and teaching of history, as well as the debate on education in its political and ideological dimensions referred us not only to a set of items kept, but also allowed us to track some reading and writing practices, visible to the way he dealt with the organization of his work material. They are bound in a letter size with around 300 pages that the team initially called dossier and later compendium.

This material is composed of newspaper clippings, authorial texts, articles on the few specialized magazines at the time, and parts or books or any printed material that could be considered useful to store and gather information on specific themes. The intellectual ambivalence of the period justifies such creation, as many of the themes, due to its topicality or originality, did not have consistent and available studies. The daily activity of clipping newspapers and classifying the data collected - already during breakfast time- reveal the dedication of this teacher to the everyday task of organizing, grouping, and giving a coherence to the elements that, together, express the paths apparently taken to prepare his innumerous activities of intellectual mediation.

This idea referred us to the volume and diversity of materials and marks seen in this Archive, showing the apparent incoherence that trespasses the textual documents, illustrations, maps, reference books, abstracts and content tables, among other archived documents. We see a cornucopia of material, data, and information that, in some moment, stopped to signalized chaos and acquire the format demanded to identify the cultural product that we call book, in its final configuration. Borges (1998) considers that a Library is the result of combinations of everything that is expressed. We refer to the wish of the Archive holder to organize what he read and collected daily, producing a support that he considered appropriate to do so, a type of cyclic book, a compendium, as a way to corroborate so many other supports in his library, and for consultation purposes. It is interesting to mention the existence in the archive of several sets of clippings that were not bound, thus becoming a compendium. The fact that it is not bound does not remove the cyclic character of the compendiums, as some of these supports were added of materials considered pertinent to the themes clipped, even after the bidding.

In the Archive he also registered some reading and writing practices, through marks that allowed us to notice the routine of clipping his readings associated to the intense dialogue with the renovation of History writing,17 and the creation of a pedagogical bibliography. This observation led us to conclude that the innumerous evidences of intellectual mediation to which Aquino dedicated his life - and that are documented in his Archive - establish an integrated practice. His reading practices are associated to the actions inscribed in the creation of the compendiums, gathering data and information that fed not only the class plans, but also the writing of booklets and didactic books, as well as present in other types of authorial texts.

Source: Authors.

Figure 5 Photo of an open compendium. In the collage, an news article on Professor Manoel Maurício de Albuquerque, of FNFi, who lost his position in the institution after the establishment of the military regime.

In the records of the multiple activities Aquino developed, there is much of himself, his identity as a teacher, also revealing his sociability network. On this, it is important to observe the mixture of generations that composed the sociability nets he interacted, through the citations and references present in the documents of his Archive, as well as the co-authorship of booklets and didactic books. First, it calls out attention the friendship he established with former professors of FNFi, where he completed his Bachelors’ in 1963. After that, there were teachers from the courses he worked and authors for the history booklets for the university admission test. From this partnership, we can see some participations in didactic books and co-authorships with younger generations, including some former students.

On the other hand, said Archive has many challenges due to its heterogeneity and diversity. It has reached us already fragmented and thus we can consider it a sample. However, we should stress that what defines its complexity is not its size, -- that is, the one measured by a ruler measuring the height, width, and giving us a hint of its finitude --, but the potential it represents, arising in us this utopic will, as pointed out by Farge (2009), of one day completely take hold of it. When we finally see ourselves faced by a document set, over which it is possible to elaborate a description, a new challenge emergesso as not to create precipitated interpretations, due to a forced intimacy.

To treat and systematize the archived content, it was very important to create a controlled and objective terminology to identify the items in the Archive. This is done in articulation with a methodology of classification, cataloguing, and indexing that are not restricted to the areas of Archival Sciences and Librarianship, as the document collection gathered could lead to diverse uses, interests, and interpretations. Thereby, we took advantage of our multidisciplinary team to have long debates on the best and most adequate way to call each type of document.18

Regarding the bibliographic material, our participation was to check items related to the “subjects” present in the access table to the archive, observing cases of duplicity and producing associations and equivalences to make feasible the access to future researchers. To create the descriptors we needed to observe, flip through, read, and process the pieces related to 322 volumes present in the Library. There are still folders with booklets, didactic material and possibility proto-materials under processes, these can be gathered to create new compendiums but were not yet bound. Thus, during the work of revising the descriptors identified by the team to compose the list of documents, we considered, for instances, the notes from his reflections on the news of the time, in the constant discussion between past and present, as well the attention to articles that approached the historiographic debate of the time, or those that released research results that interested him to his teaching and writing activities, among others.

Such diligence and discipline of the holder are shaped to a daily life dedicated to teaching and committed with the reflection on the present time. These two activities are unmistakably associated. The archiving is articulated, in this case, to a practice of intense bricolage, an interposition of collages, clippings from his daily reading and teaching, together with letters, dedications, and booklet texts. There is much of him there, of his subjectivity, but also much of his concepts on teaching, curriculum, and formative virtualities of school education. Beyond the documents kept, we paid attention on the marks left by the holder on the books to be updated, the class plans to be adapted to different classes, the compendiums that would ground the writing of booklets, and the transposition of their parts to create didactic books.

As we have highlighted, some of the challenges faced in the organizational work of the Archive were noticed from the reading of Arlette Farge’s (2009) text “The Allure of the Archives”. After starting processing the bibliographic material, some distresses echoed. These anxieties are common to those who, beyond organizing, also wish to research the Archive with which they are interacting. A first challenge was related to the diversity of materials that compose it, with repetition of pieces, overlapping, collages, as well as the need to control the expectation that hit us as we started to explore the Archive to consider each detail as a potential indication to answer our questions. However, as the research progressed, it was possible to identify more precisely what should be observed according to our research questions.

Final remarks

The excessive perfectionism of a daily life shaped by reading protocols and writing practices draws a pathway through which the pedagogical material in the Archive engenders the creation of his books, mostly written with other authors. Thus, they highlight a network of sociability and their concepts with history, its teaching, and even life experience. Finally, we stress, as a theme and methodological articulation, that there are evidences of an integrated practice of reading, writing, and production of materials connected with teaching that, in the end, will result in the publication of his books, didactic and essay ones.

On the other hand, it is in these traces of teaching practices that we can understand the intense derivation of it and through it, in its imbrication on the reading protocols and the marks that precede writing and teaching, which we can perceive in the compendiums. The continuous assemblage of printed materials present in his everyday life and kept in his Archive expresses the snapshots of reality Aquino considered to be interesting to his work and activism. In this pendulum movement of observation/organization/typification and dialogue with the items of such material, in the complexity of his Archive, this reader, teacher, author of multiple facets delimits himself, though imprecisely by us.

The dialogue with the social history of reading and writing, in the line proposed by Roger Chartier (1996), has instigated us to search for the historicity of the documents written, paying attention to the marks that indicate not only the presence of the Archive holder, but his ways to interact with the archived items, combining, non-stop, everything he read and that could have been useful to his incursions on the universe of historical knowledge.

Through very particular reading practices and, at the same time, amidst the possibilities established by the historiographic renovation of that time19, the holder of the Archive articulates the bases of his writing and produces his interpretations, giving them topicality, coherence, and consistence. The varied weaving of the texts gathered in these compendiums answers then the expectations of intellectual production and the mediation of the knowledge produced from the first readings of the day, passing through their selection, classification, and grouping, until the writing, review, and following updates.

The ways of appropriation, as well as the strategies of dissemination of his publications, would demand an analysis of the resulting writing production, the reception of students and other teachers, and editorial strategies to release his books, what escapes the scope of this article. On the other hand, the observation of the ways to compose his authorial publication led us to focus on the spaces and sociability networksin which Aquino has circulated, pointing out the need to consider the multiple contexts - intellectual, pedagogical, cultural, among others - that weaved and entangled his authorial texts, a theme that demands continuing our studies and, therefore, cannot be deepened here.

Beyond the unfoldings of this study, in these final remarks, we wish to highlight that it is in the configuration of personal archives that we can glimpse the traces and evidences of a personal and professional trajectory. The evidences highlighted in this article articulate aspects as the organization of knowledge bases to be configured in different filing supports and types of writing, considering, among them, the operations of selecting, composing, altering, reediting, collaging, post-additions, as primordial elements of the materiality of reading and writing practices perceived through the constitutive marks of the items kept.

Thus, despite the risks, we have made an effort to understand the pedagogical Archive of teacher Rubin Santos Leão de Aquino as a creation of self, that is, the holder of the Archive. However, we also believe it is possible to know more about teaching culture, especially the generation of history teachers in preparatory courses in the south region of Rio de Janeiro, between 1960s-1990s. Working on approximation and separation, we believe it would be possible to draw, from the evidences shown here, a portrait on the structures of feeling that permeated the expectations of teachers who articulated teaching and political activism, as did Aquino, together with peers who shared the same utopias, feelings, and political projects.

We have then attempted to articulate the different social roles portrayed here: the teacher, writer, producer of didactic books, teacher activism, and an activist on many causes. Among those causes, we highlight his effort to disseminate the knowledge of an alive and engaged history, through the education of youth; the expectation of interfering in the political pathways of the country and the sharing of a structure of feelings involving many teachers, artists, and intellectuals of a generation who lived the repression time imposed by the military dictatorship and the process of democratic construction which followed the end of this regime20. As observed by Ridenti (2000) on the artists of the 1960s-1970s, this structure of feeling could be seen on the criticism of national reality, associated to a certain idealization of the ‘man of the people’, his simple character and, in a certain way even naivety, but, at the same time, full of revolutionary potential and genuine inclination towards the engagement on a fight to build a society grounder on political freedom and social justice. How we miss these times!

REFERENCES

BAHIA, Bruno. As negociações identitárias do professor de filosofia no Ensino Médio da escola pública no Rio de Janeiro: tempo, experiência e seu lugar na escola. 2016.330f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, 2016. [ Links ]

BORGES, Jorge Luis. A Biblioteca de Babel. In: BORGES, Jorge Luis. Obras Completas: Ficções.v.1. São Paulo: Editora Globo, 1999. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A invenção do cotidiano: as artes de fazer; 16 Ed., Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2009. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger (Org.) Práticas de leitura. São Paulo: Ed. Liberdade, 1998. [ Links ]

FARGE, Arlette. O sabor do arquivo. São Paulo: Edusp, 2019. [ Links ]

GOMES, Ângela de Castro; HANSEN, Patrícia Santos. Intelectuais Mediadores: Práticas culturais e ação política. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2016.489p. [ Links ]

HEYMANN, L. Q. (1997). Indivíduo, memória e resíduo histórico. Estudos Históricos. Rio de Janeiro, CPDOC-FGV, n.19, pp. 41-66. [ Links ]

KOSELLECK, Reinhart. Futuro passado: contribuição à semântica dos tempos históricos. São Paulo: Contraponto, 2006. [ Links ]

MILLS, Charles Wright. Sobre o artesanato intelectual e outros ensaios. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed, 2009. [ Links ]

RIDENTI, Marcelo. Em busca do povo brasileiro: artistas da Revolução, do CPC à era da TV. Rio de Janeiro-São Paulo: Record, 2000. [ Links ]

SILVA, Amanda. Tempo e docência: dilemas, valores e usos na realidade educacional. Jundiaí: Paco Editorial, 2017. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, Jean François. Os Intelectuais. In: REMOND, René. (Org.). Por uma história política. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ-FGV, 1996. [ Links ]

TARDIF, Maurice. Saberes Docentes e Formação Profissional. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. [ Links ]

XAVIER, Libania Nacif. Relações e vínculos evocados no ato de ensinar. Tese apresentada à Faculdade de Educação da UFRJ para progressão à categoria de professora titular, outubro de 2018 (mimeo). [ Links ]

2On the dimensions of time present in the organization of the work of K-12 teachers, see the studies of Silva (2017) and Bahia (2016).

3Though each safekeeping institution has specific criteria to select the Archives under its care, we can affirm that, in general, personal Archives are those whose holders held a public position or were renowned academics and/or artists.

4On the concept of intellectual mediators, see J. F. Sirinelly (1989); Gomes and Hansen (2016).

5The Pedagogical part of the Archive is preserved in the Educational an Society Program of Studies and Documentation - Proedes / UFRJ.

6At Proedes-UFRJ, the organization was coordinated by Michele Almeida, with the participation of the then master student Michelle Robert and the undergraduate students Mariana Correa e Mariana Vieira, under my supervision.

7The initial organization of the Archive was carried out by the historian, librarian, and friend of the family Vera Lúcia Medina Coeli.

8The other document sets were distributed by the family so as to contribute for their availability for public consultation in pertinent safekeeping institutions, such as Arquivo Público do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (APERJ), which received the documents on military dictatorship in Brazil and his actions in the Comitê Pró Anistia and Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais; the Museu de Arte Moderna (MAM), which received books and DVDs of his archive; Museu da República, which received the material on the Republic; Departamento de América Latina da PUC-Rio, with the documents on the region, and the Centro de Ciências Humanas da Universidade do Recôncavo Baiano (UFRB) that received around 700 items among books and videos.

9A time not to be forgotten, testimony given to Mário Lúcio de Paula and Patrik Granja. Nova Democracia. Ano IX, n.06, June 2010. Available in: http://anovademocracia.com.br/no-66/2836-um-tempo-para-nao-esquecer#n2. Accessed in April 26, 2018.

10We use the terms arts of teaching, as a reference to Michel de Certeau (2009), to whom the ordinary subjects, that is, who do not hold positions of powers, cannot be reduced to simple reproducers of discourses, rules, and prescriptions imposed to them, but they act as agents that reinterpret these discourses and rules, during their everyday life, developing their arts of making.

11The Library is composed by 322 items, among didactic and academic books; booklets and leaflets, collections of texts and selected documents, atlas, dictionaries, etc. We can see a strong presence of French didactic and history books.

12On books see: DEIRÓ, Maria de Lourdes Chagas. As belas mentiras: a ideologia subjacente aos textos didáticos. São Paulo: Moraes, 1978; and FARIA, Ana Lucia G. Ideologia no livro didático.16. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008.

13Translator’s note (TN): The thin figure says “You are killing me”. The doctor says “And, in the future, you will be underdeveloped”. On the briefcase, we can read the words “Colonial pact”.

14TN: Behind the wall, the man says “I am embarrassed to be the censorship!” The man on the left with a sword raised proclaims “I am the State religion”, the one in the middle states “I am the mercantilism”, on the right the man says “I am the Divine Right”.

15As shown by Reinhart Koselleck (2006), past and future are contained by the present, be it as memories of past experiences that guide our decisions, or the expectations we have in the present that will happen in the future.

16The Faculdade Nacional de Filosofia was created by a decree in April 1939, connected to Universidade do Brasil, with four sections: Sciences; Mathematics; Chemistry; Natural History; History and Geography and Social Sciences. According to Ferreira (2013), until the 1960s, the section History and Geography privileged the training of secondary teachers, using a conception of national, factual, history, focusing on the great historical characters and their feats.

17The movement of historiographic renovation is portrayed through newspaper clippings, highlighting the approached of English social history, that criticized positivist and nationalist history and identified itself with a type of Marxist approach closer to the study of subaltern classes and interdisciplinary dialogue.

18In the team, there were two undergraduate researchers from the History Institute and two from the Pedagogy undergraduate degree, as well as a Master’s student graduated in Letters, a member of the Archival area, and another from History of Education.

19Though we have not done a thorough survey of the historiographic references of his writings, the influences of English social history can be seen, through the interdisciplinary approach of the historical events, as well as the interest to study the history of the working classes, their habits, and emerging movements.

20On the topic, see: Ridenti (2000).

Received: November 04, 2020; Accepted: February 24, 2021

text in

text in