Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.20 Uberlândia 2021 Epub Jan 29, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v20-2021-47

Dossier - Traces that leave traces: personal archives and present time

A suitcase, an archive: ordinary writing in notebooks used outside school settings1

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas (Brasil). vaniagrim@gmail.com

Except in rare cases, women are responsible for keeping family memories. Personal archives and their objects in different media reveal how social and sensible are everyday traces. In that context, this paper seeks to analyze the personal archives of an unschooled woman to understand how written records support those memories. The subject of this research is an ordinary woman who recorded accounts, lists of names and surnames, regional, national, and world events, and others. We analyzed six notebooks used outside school settings that correspond to different periods between 1946 and 2012. They reveal traces of rural, everyday life through ordinary writing. Theory and methodology for this paper are based on Cultural History premises. It contributes to History of Education and to Contemporary History by analyzing ephemeral records.

Keywords: Personal archives; Ordinary writing; History of Education

A guarda da memória familiar é destinada às mulheres, salvo raras exceções. Os arquivos pessoais, com seus objetos em diferentes suportes, são reveladores de sociabilidades e sensibilidades dos rastros cotidianos. Nesse sentido, o presente artigo tem como objetivo analisar o arquivo pessoal de uma mulher com pouca escolarização, de modo a compreender os registros escritos como suporte de memória. Trata-se de uma pessoa comum que registrou contas, escreveu listas de nomes e sobrenomes, acontecimentos regionais, nacionais e mundiais, além de outras coisas. Foram analisados seis cadernos de usos não escolares que compõem temporalidades distintas entre os anos 1946 a 2012, trazendo os registros de traços do vivido no cotidiano rural por meio da escrita ordinária. A discussão teórica e metodológica está ancorada nos pressupostos da História Cultural e traz contribuições à História da Educação e à História do Tempo Presente por meio dos registros efêmeros.

Palavras-chave: Arquivos pessoais; Escritas ordinárias; História da Educação

La guardia de la memoria familiar es destinada a las mujeres, salvo raras excepciones. Los archivos personales, con sus objetos en diferentes soportes, revelan sociabilidades y sensibilidades de los rastros cotidianos. En este sentido, el presente artículo tiene el objetivo de analizar el archivo personal de una mujer de escasa escolaridad para comprender los registros escritos como apoyo a la memoria. Se trata de una persona común que registró cuentas, escribió listados de nombres y apellidos, hechos regionales, nacionales y mundiales, además de otras cosas. Han sido analizados seis cuadernos de usos no escolares que componen temporalidades distintas entre los años 1946 y 2012, trayendo los registros de rasgos de lo vivido en el cotidiano rural por medio de la escritura ordinaria. La discusión teórica y metodológica está basada en los presupuestos de la Historia Cultural y trae contribuciones a la Historia de la Educación y a la Historia del Tiempo Presente a través de los registros efímeros.

Palabras clave: Archivos personales; Escrituras ordinarias; Historia de la Educación

Introduction

The start of our life2! Based on this short phrase, I state that accessing private memories is no easy task, especially when it comes to family archives permeated by bonds of affection. Working with personal archives is about working with the memory of what is private (PERROT, 2005). It is about reflecting on relationship networks and on the history of certain subjects who keep those documents. I was inspired to write this paper by a personal family archive carefully maintained by the hands of a grandmother, who handed it to her granddaughter, this author, a suitcase full of papers and objects, most of them kept for over a generation.

This paper, therefore, seeks to analyze the personal archives of an unschooled woman kept in six notebooks used outside school settings to understand how written records support memory. The subject of this research is an ordinary woman who recorded family accounts, lists of names and surnames, songs, birthdays, local, regional, national, and world events, and other information.

The collated archive was organized in a suitcase and includes not only documents by the person who kept her records on the notebooks analyzed here, but also rolled-up invoices tied with colorful ribbons, scattered documents from other family members, and some personal use objects (pieces of clothing, glasses, coins, etc.). Judging by the dates and names that appear on them, most of that material belonged to previous generations of the family.

According to Perrot (2007, p. 30, translated), “organizing archives, maintaining them, keeping them - all those activities impose a certain relationship with oneself, with one’s own life, with one’s own memory”. By stating that, Perrot (2007) points out that destruction and self-destruction are more frequent than keeping one’s material. One example are women’s journals, which are often burned before their authors get married. Analyzing the history of women in the 19thCentury, Perrot (2005, p. 37, translated) states that “women trust their memories to the silent and acceptable world of things rather than to the forbidden world of writing”. If writing is forbidden, women most frequently trust their memories, their “thousands of nothings”, to objects that have been kept and collected.

It was under that perspective that I noticed the silent history of a grandmother when I received an archive in a suitcase, the history of a simple woman, a farmer who attended school only for a few years. When she arranged her belongings, she entrusted the next generation of women with her own memories in the form of written documents and personal objects towards which she nurtured affection. This takes us, thus, to what was left “of women of the past in women of today (which is not little)” (PERROT, 2005, p. 39, translated): a suitcase yearning to be opened, “exposing baubles and relics of family and group memory from that time [...] making it possible for historians to get to know details about social, cultural and political events of a given period” (CUNHA, 2019, p. 102, translated).

The task of maintaining men’s memories also fell upon the woman who wrote the notebooks analyzed here. In this particular case, those men had no political or social standing. The suitcase also includes documents from the men in the family who served the military between 1942 and 1945. This confirms the claim that women are trusted with keeping family memory.

Records found in the notebooks not only show awareness and sensibility towards herself but also towards social relationships and to news from around the world. Those notebooks combine everyday writing, as in the journal genre, and domestic ledgers, as well as fragments of local, regional, national, and international history. They are dated from a specific historical period, written in a domestic setting, and reveal order in daily life, never losing their touch with a broader social context. These sources contribute, thus, to the historiography of education, being at the crossroads between the present and longue durée (DOSSE, 2012).

Called “ordinary writing” by Daniel Fabre (1993), these types of sources refer to writing with no scientific quality by ordinary people, as opposed to prestigious writing created with the intent of publishing a work in print. That definition indicates that even people who do not use writing in their professional activities use it and create a variety of records on different supports. They are the writing of ordinary people (GÓMEZ, 2003), who are usually not very literate and who have attended school only briefly, and who use writing for personal reasons, leaving behind traces of their everyday life. In turn and in a certain social and historical context, those traces “allow historians to track in the present many ways of living and thinking from any given” (CUNHA, 2013, p. 252, translated).

Fragmented, written documents, often in the form of lists, local events, regional news, and some world news. Furthermore, a record of sales and sparse notes about renovations in the house or repairs in barns at the farm. A written autobiography by a rural woman who lived in southern Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) and who attended primary school only for a few years during the 1930s. Writing with spelling mistakes and swapped letters that show a low level of orthography knowledge, produced by this woman from Pomeranian ancestry3 - who used one language or another depending on the context, speaking Pomeranian at home while attending school in German. From the records included in her school notebooks4, dating from 1938, written in German and in Portuguese, I was able to ascertain the influence of the process of schooling nationalization at the time, when the use of German was banned. She also spoke Portuguese in formal events outside domestic settings5.

Notebooks analyzed here reveal their uses by registering everyday facts from 1946 to 2012. Writing in them intertwines ledgers that include accounts from the household and from the rural property with writing about the author herself, writing aware of the dates of family occurrences, and everyday writing of events and trivia, probably heard through the media (radio and television). What do these traces indicate? How writing about such contemporary times contribute to the History of Education?

From private life to international events: records in ephemeral fragments

All six notebooks analyzed here were used to record the most ephemeral of everyday occurrences, from lists of names to a timeline of one life, indicating its most important dates. Because of that, they were not organized chronologically year after year or even day after day. They date from different times between the years of 1946and 2012. In a single notebook, there are records from several years, all written in ballpoint pen (blue, black, red, and less often, green). From that fact, we can infer that the notebooks were revisited at different moments, possibly to add some information or to remember others. Therefore, even if this analysis tried to follow some sort of chronological sequence, it has not always matched the actual writing timeline, as the notebooks were used and revisited several times.

Another factor that came up during the analysis of the notebooks, which are the historiography sources for this study, had already been highlighted by Hébrard (2000): the “graphic space” that switches between different functions.

Interconnected, it comprises a homogeneous continuum that follows both the rationale of time (memorial, journal, diary) and the rationale of reason (large book), as well as the division of labor (supporting books). Through writing, this continuum offers early and multiple ways of accessing a translation of the complexity of the world. It allows the application of subtle perspective-changing techniques for the same operation, which offer different views on the same reality (HÉBRARD, 2000, p. 45, translated).

The words of Hébrard (2000) help to reflect on function, reason, and different times for each of the six notebooks described below. What I mean is that each notebook was used with no concern for sequential writing, year after year. Writing and information were added as necessary, as imposed by everyday life on the farm, or whenever the author of the records felt the need to go back to writing, adding details. For better understanding, each notebook will be described in a way as to highlight any information that is relevant for the analysis. As a researcher, I tried to determine an order of description according to the year each record was made even if the dates do not follow a strict sequence, as mentioned above.

The first notebook6 does not include dates on any of its 15 sheets, it only includes the year, 1947, on the cover alongside the name of the author of the records and the place. Out of the whole set of six notebooks and considering all documents, this is deemed the first notebook as we ascertained that the author of the records married in 1946.

Recording is a way to archive memory of private matters, as if one needs to know “about family and everyday life, ask women!” (PERROT, 1989, p. 17, translated). I understand that the desire to record traces of what has been experienced at the beginning of married life in a role of “memory keeper” stems from a desire to make the present and the past visible also in the future. Those records, thus, are to be maintained and read again, in a feminine continuity of memory.

Besides its sheets, the first notebook includes loose papers, such as invoices for purchases, lists, advertisements for radios, and notes about a clock (date of purchase, first repair, and second repair): “Este relógio foi comprado ano 1934. Teve 20 anos parado des Novembro 1971. Começo trabalhar 21 de abril 1991. Foi na reforma 19 Outubro 2007. Custo 40.00 real”7.

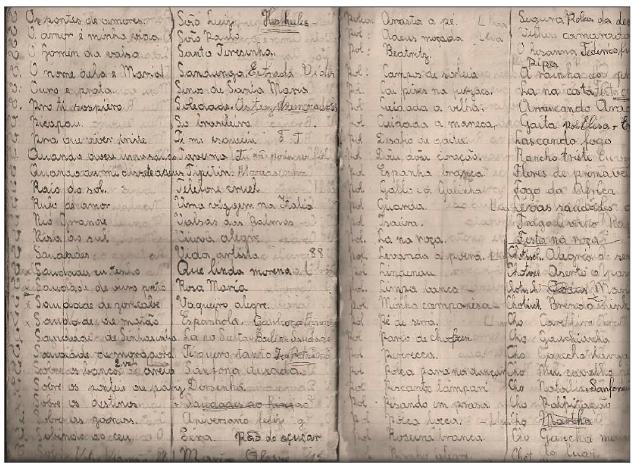

On the sheets on the inside of the notebook, there are handwritten days and months alongside the name of people and the city or place from where they are. Judging by how the records were made (day and month, with no year), we can infer that they are birthdays. On the last three sheets, there are lists with the name of songs and their respective genres (waltz, rancheira, polka), in some sort of genre compilation. On the margins of the notebook, there are notes indicating waltzes with the letter “v” [for “valsa”, orwaltzin Portuguese] and polkas with the notation “pol”, as we can see in Figure 1.

From the different colors of ballpoint pens used for the inscriptions, we can verify that their author revisited the notebook throughout the years, adding new names to the list of birthdays, as well as new songs and genres. Writing in lists is something recurring in this notebook and in all other notebooks analyzed. According to Eco (2010), as a list shapes a series, it orders a set that would otherwise be disorderly. Writing in lists is also associated with a lower level of writing appropriation, as it is easier for its intended purposes: archiving names, songs, birthdays, and other everyday matters.

The way the sheets of the notebook were used is also interesting. They were divided into two columns and used in full as if there were no margins or lines. Was this need to fully use all space available for writing due to fear of not having another notebook in which to continue to write? Or can we ponder about the use of this support medium outside of a school setting, with a personal purpose, allowing the author to use the sheet with no concern for rules, but “focused on a sense that time goes by and on the writer’s efforts to create a representation and a memory from that sense” (HEBRÁRD, 2000, p. 30, translated) at different points of her life? Faced with so many everyday senses inscribed in the notebook, we must ask: which representation and which memory does writing seek to preserve?

There are several pieces of information we can only understand by analyzing records from all six notebooks. As an example, I can mention a drawing in the form of a blueprint for the construction of a house, found in a piece of paper among the sheets of the first notebook. In that drawing, made in pencil, there is writing in pen dating it to June 1932. This information can only be fully comprehended by analyzing the sixth notebook, which lists the major events in the life of the author (a summary of events experienced) and their respective dates. One of those events records the following: 1962 - Este comsemos a casa 13 de junho, fico proto 13-12-19628. As a blueprint for construction, this small piece of paper represents an intention, as well as a project for the family home. Most likely, the date inscribed in pen was added many years after the blueprint was made.

It is important to analyze, therefore,a personal archive as a whole, crossing information to reveal certain relationships among the set of sources that were archived, as anyone who archives something does that with a purpose: that someone in the future reveals the old papers, reads them,bringing up a reflection on the present.

We can understand the second notebook as a ledger, as it includes the accounts for the farm. As Hébrard (2000, p. 38/39, translated) explains, “a livre de raison [ledger] is a book in which a good manager or businessperson writes down everything they receive or spend to account for their business and to explain to themselves the reason for it”. With no cover and many blank sheets, recording is guided by seasonal or yearly “safras” [“harvests”]9 of crops raised by the family between 1953 and 2003. It includes records for fifty years of produce sold, as well as respective quantities sold or harvested, prices, weights in kilograms of each produce, and buyers.

The author organized those ledgers to explain to herself all domestic accounts. For each record about a harvest, there is one or there are several blank sheets, as if other information still had to be added throughout the years. As well as recording harvests, she also recorded costs from repairing barns and purchasing furniture, animals, and other items for work on the farm, such as tools, seeds, etc. The notebook does not belong to someone from the business world, but it seeks to monitor the author’s own life, which means writing is “directly connected to its everyday uses” (GÓMEZ, 2012, p. 69, translated).

Among the records of accounts, between onion, potato, garlic, peach, flower, and vegetable harvests, there is also the record of a trip to the state of Paraná, entitled “dia 27 de abril 1971! Um passeio S. Helena Paraná [April 27, 1971! A trip to S. Helena, Paraná]. The two-page text describes the bus itinerary through major cities and the travel time there and back, as well as promenades in the visited city, as a travel journal. It includes a brief account of each day between the start of the trip on April 27, 1971, until May 12 of that same year, the date of return. It finishes as follows: “Toda viagem custo 350 cr. Fim!”10.Once again, I seek in Hébrard (2000) the inspiration to understand this motion to order life through written fragments scattered throughout a ledger. A mixture of accounting with records of leisure activities give order to what was lived and experienced:

Recording financial accounts and events of life are similar acts that increasingly intertwine. The graphic space for double-entry recording is a place where written elements offer multiple possibilities to grant an order to the dispersed actions of life (HÉBRARD, 2000, p.39, translated).

Among different records, the archive reveals different aspects of life with different facets, encompassing different moments, from trips taken to costs of repair for a barn or the sale of a dozen eggs. Everyday writing leaves traces of and orders different “disperse actions of life” (HÉBRARD, 2000) from farm routine.

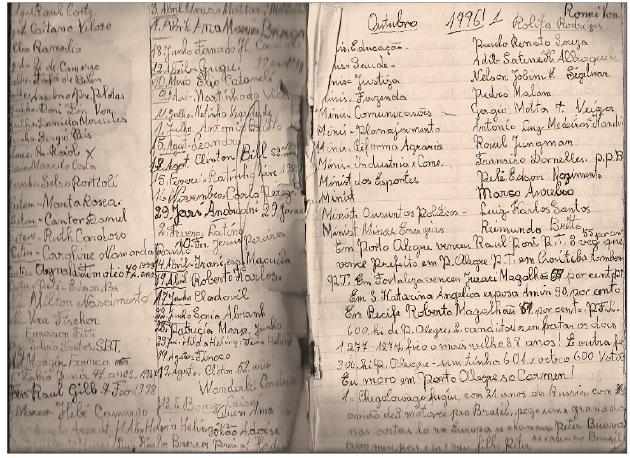

The word “Companheiro” [Companion] is printed on the cover of the third notebook, referring to its brand. The back cover includes the Brazilian flag and informs the extension of the country’s territory and an estimate of its population. It comprises 52 numbered pages. Writing is spread throughout the cover and the sheets with no spaces between lines as well as on the margins, which means there are no blank spaces - hand written content occupies all spaces. There are records from the years 1996 to 1999, indicating on the margin the day and month (mostly abbreviated) when each record was made. The reference year is at the top of each page. Figure 2 presents an example of how writing is organized in the third notebook.

Again, lists appear in the notebook. This time, they include the names of influential people, probably heard through the media, such as Ministers (Education, Health, Justice, Treasury, Communications, etc.) of the Federal government, Brazilian singers (Milton Nascimento, Fafá de Belém, Martinho da Vila, etc.), and other. Once again, I appeal to Umberto Eco (2010), who corroborates this debate when he states the following: “The technique of the list does not intend to question any order in the world, on the contrary, it intends to reiterate that the universe of abundance and consumption available to all represents the only model of an organized society” (ECO, 2010, p. 353, translated). Writing analyzed here includes names that were probably heard through the media, organized as inscriptions by dates (date and month) as a way to order abundant information.

The third notebook described here is of the journal genre. It does not include intimate writing, however, as its writings present local (municipal elections), regional, national, and international events. Here are some more examples beyond those already mentioned above: birthdays, aviation disasters, the death of Princess Diana, the death of Brazilian singer Renato Russo, an earthquake in Italy, a storm in India, occurrences in Russian coal mines. Thoserecords from small and large events alike “contribute to our understanding of the recent past of our society and encourage us to reflect about connections between past and present” (CUNHA, 2013, p. 259, translated).

Furthermore, these records also include some trivia, copied poems, an advertisement for a parody contest, songs that were written down, names of singers, and titles of soap operas and other TV shows. The final sheets show names of players for the Brazilian national soccer team, as well as the names of players for the national teams of Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands in 1998, when the soccer World Cup was held in France.

Therefore, we can see that topics such as politics, economy, the weather, agriculture, sports, and art appear side by side in everyday writing. Some selected examples are worth mentioning:

Em Porto Alegre venceu Raul Pont PT. 55 por cento. 3 vez que vence prefeito em P. Alegre PT em Curitiba também (...)11 [October 1996].

30. Ago. Morreu princesa Diana em Pariz com 36 anos! Em 1981 casos e Charles, deixa 2 filhos, 1 irmão, 2 irmã nasceu 1 Julho 1961. Os Willian 15 anos Harri 13 anos12[August 30, 1997].

12 Marco - Forte chuva e temporal hoje no Rio de Janeiro [March 12, 1998: Strong rains and storm today in Rio de Janeiro]

21 de Julho Nelson Mandela 80 anos Sul Africano visita Brasil [July 21, 1998: Nelson Mandela, 80 years old, from South Africa, visits Brazil]

The notebook also includes notes about the beginning or the end of soap operas, as well as the name of a brand of face cream, and names of Federal Ministers and their respective offices. In light of so many variables and diverse subjects, we must pose several questions while reading the empirical evidence: What kind of selection was made by the author of the records? Why are such different themes recorded together? Where does that information come from? The need to apprehend information about the most diverse aspects of life is prominent in records in a journal.

As Artières (1998) contends, we do not archive our lives in just any way. According to him, “we make a deal with reality, we manipulate our existence: we omit, we erase, we cross out, we underline, we highlight certain passages” (ARTIÈRES, 1998, p. 11, translated). In these notebooks, we can notice the author’s concern for organizing her personal life without ignoring her social life and important information from around the world or from close by places.

For that reason, information recorded seems dispersed, but in truth, it comprises its author’s personal life and considerations about it, according to a selection made by her: Traces of her personal life recorded in notebooks alongside local, regional, national, and international events appear together with dates and numbers.

When I was creating an organigram of the documents, I searched for evidence to help understand and observed evidence that explains why writing was so precise on dates and other information involving numbers. Other documents from the suitcase, such as invoices and payment slips, helped complement that data. Noticing the purchase of the first battery-powered radio in 1963 and the arrival of electricity to the family’s rural property in 1994 and crossing those events with other data from the notebooks themselves led me to conclude that the details were heard and seen through the media, then recorded on those notebooks. Furthermore, my memory as a woman who is the grandchild of the author of the records was jogged, and I remembered that on the piece of furniture on whichmy grandmother’s radio and her television were placed, there were always a notebook and a pen close at hand.

The fourth notebook only has its front cover, not the back one. As in the records from the third notebook, the fourth one is also a journal of local, regional, national, and international events by their respective date and abbreviated month on the margin, as well as a brief inscription about what happened that day. References to the year are at the top of the page. Sheets in this notebook were numbered up to 85. Out of those sheets, 62 have writing in them, and sheets from 80 to 85 were torn up.

Records are from August 1999 to 2012. For 2012, there are only brief notes for just some of the months of the year and that include names of a few people. On these manuscripts, we can see that the calligraphy is different from previous notes and that letters seem shakier, which indicates writing was not as regular and not done every day anymore.

Among those few records for 2012, I would like to highlight two notes that appear in the following order: the death of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemayer (December 5, 2012), and notes about the municipal elections in Morro Redondo (October 7, 2012), a small town in the state of Rio Grande do Sul where the author of the records lived at the time. The records for the election include the name of the candidates for mayor alongside the number of votes they received, as well as the name of the elected municipal council members alongside the number of votes each received.

Both records, one for an international event (Oscar Niemayer) and another for a local event (municipal elections), point to the concept of “glocal”, as defined by Chartier (2009): “processes through which shared references, imposed models, texts, and goods that circulate worldwide are appropriated to make sense at a specific time and a specific place” (CHARTIER, 2009, p. 57, translated). This presents Education Historians with some questions about those documents: How does a woman from a rural background, who attended school for only a few years, includes in her records local, regional, national, and international events? Furthermore, why did she keep non-school notebooks in a private archive until she was old enough to write in them?

The fifth notebook includes records dated from years 2005 to 2012. There are blank sheets at the beginning and the end as if there was much still to be written. Sheets and the back of the front cover were divided into two columns for writing. Manuscripts show lists with monthly dates and full names rather non-chronologically. The focus here does not seem to be any precise sequence of dates or filling line after line, but the intention of recording experienced events.

Loose sheets found together with this notebook include information about the seniors’ club the author attended, announcements for meetings and social activities held by the club, such as monthly balls, and messages about those seniors. Crossing writing on the notebook with data from loose sheets, I verified that those lists indicated dates and locations (name of the venue) where those balls were held, alongside the name of the band who played in them, and names of friends who attended the ball and with whom the author of the records danced.

We can verify there is some relationship between the information recorded in lists and the division of sheets into two columns. Writing in lists seems to be an easier way to organize information in light of a fear of not being able to recount them all (ECO, 2010), so the most important details are written down and facts are presented more succinctly. Is the lack of continued education an indication of the reason why life events were recorded as lists? Maybe this answer is not possible due to the limitations of the sources used in this analysis, but it is a point that stands out because all notebooks analyzed here include lists with different contents.

The analysis of the sixth and final notebook reveals records made between the years 2007 and 2012. Like the first notebook, it includes lists with songs and their genres (more waltzes, more rancheiras, more polkas, etc.). As in the first notebook, this final one also includes lists with titles of soap operas, lists with repeated names and different surnames, lists with brands of yerba mate, and the names of drugstores.

Furthermore, there is a summary of the author’s life in brief dates and in calligraphy that reveals fingers too tremulous for writing. On the top of the page, there is an inscription: “Começo da nossa vida!” [The start of our life!]. This record then includes brief notes indicating different years and a small phrase that summarizes each of them. The start of her married life on October 19, 1946, the purchase of the farm and the beginning of rural work in 1947, the birth of the twin sons at the family’s house in 1950, a surgery undertaken in 1986, various dates when furniture was purchased for the house, dates of events linked to the family’s farm life, such as the purchase of horses and the selling of milk to the farmers’ co-op... I also highlight the purchase of a “new” Bible in 2009, and finally, the purchase of Christmas lights in December 2012.

In his text entitled “O guarda-memória” [The Garde‐Mémoire/Memory Keeper] Philippe Lejeune (1997, p. 116, translated) asks “how many pages are necessary for someone to recount their life - theirwhole life? A life can be purchased on retail or in bulk. It may be recounted from the start or from the middle”. The records analyzed in this last notebook reveal the retail, as per Lejune (1997): small doses of what makes more sense to register - many things left out because they were forgotten, so many intentionally not recorded. Writing in the sixth notebook reveals a brief summary of events that occurred throughout 66 years and were summarized in two sheets. It is important to note, however, that this period is not a complete life, as currently (as of 2020) the author of those records is 94 years old, which means a lot has been left out!

Final remarks

One life summarized in six notebooks! A life that may be recounted, pondered, and remembered for several years between past and recent history. To finalize this paper, I think of the words of Koselleck (2014, translated): “How much of the past inhabits our present?” In light of this question, I would consider adding one more: How much of the future inhabits our present? What do we project, or what is projected upon us, after receiving a family archive with writing embodied in six notebooks? How much can histories recorded in those notebooks contribute to analyze our future? What is the relevance of studying writing from a regular woman, a farmer, inscribed in supports and genres that are not always easy to label? Finalizing this paper, many questions remain - more questions and fewer certainties.

The most likely answer is to continue perpetuating feminine family memories through non-school notebooks that include traces of rural everyday life, of regional, national, and world events, as analyzed throughout this paper. It is a task for historians who are interested in traces and records of everyday life and on ephemeral papers with no scientific qualities to develop continued research on personal and family archives.

Writing in non-school notebooks reveal other ways of being, of keeping family memories for oneself and for future female generations, as “women trust their memories to the silent and acceptable world of things” (PERROT, 1989, p.13, translated). Lists, names, and local, national, and world events reveal several facets of everyday life through ordinary writing, which contributes to the analysis of the recent past byHistory of Education historiography.

REFERENCES

ARTIÈRES, Philippe. Arquivar a própria vida. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v.11, n. 21, p. 9-34,1998. [ Links ]

BAHIA, Joana. O tiro da Bruxa: identidade, magia e religião na imigração alemã. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2011. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Maria Teresa Santos. (Des)arquivar: arquivos pessoais e ego-documentos no tempo presente. 1 ed. São Paulo: Florianópolis: Rafael Copetti Editor, 2019. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Maria Teresa Santos. Territórios abertos para a História. In: PINSKY, Carla Bassanezi, DE LUCA, Tânia Regina (Org.). O historiador e suas fontes. São Paulo: Contexto, p. 252-279, 2013. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história ou a leitura do tempo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2009. [ Links ]

DOSSE, François. História do tempo presente e historiografia. Tempo e Argumento. Florianópolis, v.4, n.1, p.5-22, jan/jun. 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5965/2175180304012012005. [ Links ]

ECO, Umberto. A vertigem das listas. Trad. Eliana Aguiar. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2010. [ Links ]

FABRE, Daniel. Introduction. In: FABRE, Daniel (org.) Écritures ordinaires, Paris: Bibliothèque Publique D’Information (Centre Georges Pompidou), 1993. [ Links ]

HÉBRARD, Jean. Por uma bibliografia material das escrituras ordinárias: a escrita pessoal e seus suportes. In: MIGNOT, Ana Chrystina Venâncio, BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara, CUNHA, Maria Teresa Santos (Org.). Refúgios do eu: educação, história, escrita autobiográfica. Florianópolis: Mulheres, p. 29-61, 2000. [ Links ]

GÓMEZ, Antonio Castillo. Das mãos ao arquivo. A propósito das escritas das pessoas comuns. Percursos, Florianópolis, v.4, n.1, p. 223-250, jul. 2003. [ Links ]

GÓMEZ, Antonio Castillo. Educação e cultura escrita: a propósito dos cadernos e escritos escolares. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 35, n. 1, p. 66-72, jan./abr. 2012. [ Links ]

KOSELLECK, Reinhard. O conceito de História. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2014. [ Links ]

LEJEUNE, Philippe. O guarda-memória’. Estudos Históricos, v. 10, n. 19, p. 111-120, 1997. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michelle. Práticas da memória feminina. Revista Brasileira de História. São Paulo, v. 9, n. 18, p. 09-18, Ago/Set 1989. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michelle. As mulheres ou os silêncios da história. Bauru, SP: EDUSC, 2005. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michelle. Minha história das mulheres. São Paulo: Contexto, 2007. [ Links ]

RÖLKE, Helmar Reinhard. Descobrindo raízes, Aspectos Geográficos, Históricos e Culturais da Pomerânia. Vitória: UFES. Secretaria de Produção e Difusão Cultural, 1996. [ Links ]

WEIDUSCHADT, Patrícia; TAMBARA, Elomar; Cultura escolar através da memória dos pomeranos na cidade de Pelotas, RS (1920-1930). Cadernos de História da Educação, v.13, n.2, p.687-704, 2014. [ Links ]

3Pomeranians come from Pomerania, a region located on the coast of the Baltic Sea. They descended from Slavs and Wends and worked mainly as farmers and fishers (RÖLKE, 1996). They are an ethnic group with particular characteristics, having a different language and different customs than those from other German ethnic groups (WEIDUSCHADT; TAMBARA, 2014).

4Memory and research center Hisales (History of Literacy, Reading, Writing, and School Books - School of Education/Federal University of Pelotas) maintains two school notebooks (one from 1937 and another from 1938) as well as the primer used to teach the author of this material to read and to write. School notebooks include writing in German and in Portuguese, concretely demonstrating the process of nationalization. For more information on memory and research center Hisales, please visit www.ufpel.edu.br/fae/hisales/.

6The cover shows a depiction of a Brazilian map and includes the text “Brasil: Ame-o com energia” [Brazil: Love it energetically]. The short phrase is an analogy to food items shown in the back cover of the notebook: corn starch (Maizena), sugar, and milk.

7Portuguese text was kept exactly as written on the paper, as it represents a low level of education and includes orality features. Transcription of the text and translation: Este relógio foi comprado no ano de 1934. Esteve 20 anos parado [sem uso] desde novembro de 1971. Começou a trabalhar [funcionar] em 21 de abril de 1991. Foi para reforma em 19 de outubro de 2007. Custou 40,00 reais. [This clock was purchased in 1934. It had stopped in November 1971. It started working again on April 21, 1991. It was sent for repairs on October 19, 2007, which cost 40.00 Reais].

8Transcription of the text and translation: 1962 - Este [ano] começamos a casa em 13 de junho, ficou pronta em 13-12-1962. [1962 - This year, on June 13, we started building the house, and it was completed on December 13, 1962].

10Transcription of the text and translation: Toda viagem custou 350 cruzeiros. Fim! [The whole trip cost 350 Cruzeiros (Brazilian currency at the time). The end!].

11Transcription and translation: [Outubro 1996] Em Porto Alegre venceu Raul Pont do partido PT com 55 por cento dos votos. 3 vezes que vence um prefeito do partido do PT em P. Alegre, em Curitiba também. [(October 1996) In Porto Alegre, Raul Pont, of the Workers’ Party, has won with 55 percent of votes. It is the third time a mayor from the Workers’ Party has won in Porto Alegre, as well as in Curitiba].

12Transcription and translation: 30. Ago [Agosto]. Morreu a princesa Diana em Paris com 36 anos! Em 1981 casou com Charles, deixa 2 filhos, 1 irmão, 2 irmãs, nasceu em 1 Julho 1961. Os filhos Willian 15 anos e Harry 13 anos. [August 30. Princess Diana has died in Paris at age 36! In 1981 she had married Charles, and she leaves 2 sons, 1 brother, 2 sisters. She was born on July 1, 1961. Sons Willian, age 15, and Harry, age 13].

Received: November 04, 2020; Accepted: February 24, 2021

text in

text in