Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.20 Uberlândia 2021 Epub Jan 29, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v20-2021-33

Articles

Funding for women’s education: the case of Escola Profissional Feminina in Belo Horizonte city (1919-30)1

1Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (Brasil). laterzaribeiro@uol.com.br

2Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (Brasil). lizet@uol.com.br

3Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (Brasil). luciahelena.ufu@gmail.com

This study focuses on public funds granted to Escola Professional Feminina, a vocational school for women in Belo Horizonte city during the years 1928-30. Its starting point was the following question: what arguments would Benjamin Flores have presented to convince Minas Gerais government to grant subventions to his school? The study aimed to analyze conditions and actions associated with the subsidy grant. Linked to the history of education in general and to history of school institutions in particular, the research drew on newspapers and magazines, manuscripts, typed texts, and photographs. Analysis results indicate Benjamin Flores was able to gather a set of personal attributes (as citizen, public agent, teacher, school owner) that praised him and gave credibility to back up his projects. In his career from postal civil servant to school owner, he was able to stand out in Belo Horizonte society so that the government would bet on his school as important project for the city.

Keywords: Benjamin Flores; Public funds; Minas Gerais government

Este estudo enfoca a subvenção pública concedida à Escola Profissional Feminina de Belo Horizonte nos anos 1928-30. O ponto de partida foi esta indagação: de que argumentação teria se valido Benjamin Flores para convencer o governo mineiro e federal a investirem em sua escola? O estudo objetivou analisar condições e ações associadas ao subsídio concedido à escola. Situada na história da educação em geral e das instituições escolares em particular, a pesquisa se valeu de jornais e revistas, manuscritos e datiloscritos e fotografias. Os resultados da análise apontam que Benjamin Flores conseguiu reunir um conjunto de atributos pessoais (cidadão, agente público, professor, dono de escola) que o abonavam e endossavam seus projetos. Em sua trajetória de funcionário dos Correios a dono de uma escola, conseguiu se projetar na sociedade belo-horizontina de modo que o governo apostasse em sua escola como importante para a cidade.

Palavras-chave: Benjamin Flores; Subvenção pública; Governo mineiro

Este estudio discute la subvención pública concedida a la Escuela Profesional de Mujeres de la ciudad de Belo Horizonte en los años 1928-30. Su punto de partida es la pregunta: ¿qué argumento habría utilizado Benjamin Flores para convencer al gobierno de invertir en su escuela? El objetivo fue analizar condiciones y acciones asociadas con la subvención otorgada a la escuela. Situada en la historia de la educación en general e de las instituciones escolares en particular, la investigación se basó en periódicos y revistas, manuscritos y fotografías. Los resultados del análisis indican que Benjamín Flores fue capaz de reunir atributos personales (ciudadano, agente público, maestro, dueño de la escuela) que lo elogiaron y respaldaron sus proyectos. En su carrera como empleado del gobierno y propietario de escuela, él fue capaz de proyectarse en la sociedad de modo que el gobierno apostó en su escuela como importante para la ciudad.

Palabras-clave: Benjamín Flores; Subvención pública; Gobierno de Minas Gerais

Introduction

The concern with the offering of public school to train professionals at secondary level goes back to the imperial past of Brazil. A point of reference is the high schools of crafts, which appeared in the 1870s. Despite their importance, they were restricted to capitals and cities more economically developed; which means, they were in limited number. In the process of changes in the teaching scenario after the Republic proclamation, especially with state reforms, the subject of education to train professionals returned to the Brazilian government concerns. In June 1909, the President of the Republic, Nilo Peçanha (1867-1924), authorized free primary vocational education (in capitals). With the decree 7,566, it was determined the creation of schools of artisan apprentices - again, only in capitals. The matter was not restrained to the government agenda. Civil society was involved in the issue too, as it did in national congresses addressing educational issues. Educators and intellectuals interacted and articulated around ideas, theses and plans regarding schooling and vocational education.

This is true when it comes to Belo Horizonte, capital of Minas Gerais state, where the second edition of Brazilian Congress of Primary and Secondary Education took place in between September 28 and October 4, 1912,2 an occasion for such meetings and interactions. Not by chance, theses on professional education stood out. Congress participants expressed an overall understanding of vocational education “in general”. It would be something that “should specialize, even maintaining links with secondary education,” instead of being seen as something “strictly linked to the masses” (ROCHA, 2012, p. 231). Similarly, education to train women professionally was put into question in the debate; some asked: “[As] For the perfect female education [...] in the different moral, intellectual, physic, professional and social aspects: what are the means to be used today? [...] Wouldn’t it be better to recommend the foundation of escolas maternaes [motherly schools], of escolas de profissões domesticas [vocational schools for household professions], women’s vocational institutes?” (BRAZILIAN CONGRESS OF PRIMARY EDUCATION, 1912, p. 8; 27).

These questions permeated debates at the fifth congressional committee, whose members included teachers, clergy members, and others with a doctor’s degree. Among them, Benjamin Flores, a teacher, would stand out by his action. He went from the discourse on vocational education to its very practice by founding a school in 1912 to train work force for the commercial sector, besides a school for the training of women in certain professions. Although it is uncertain the year of the school for women’s appearance, it had the longest lasting; and to some extent, such longevity resulted from the arrangements Benjamin Flores he managed to make with Minas Gerais state government as to validate the school’s certification and as to grant subsidy to it from 1919 onwards.

The grant of public subsidies to a private school raises some thought. On the one hand, Belo Horizonte city had already created its vocational school in 1910, a School of Craftsmen and Apprentices. This means the capital had already being “benefited” with the fulfillment of the federal decree of 1909. On the other hand, some public institutions in both the state and in the capital demanded subsidies grant too, which could have led to some “competition” as to obtaining public funds grant. The study3 this paper presents deals with circumstances of granting public funds to a private vocational school for women. Its development derived from the following questions: how did an initiative of keeping a private vocational secondary school manage to obtain government subventions grant? What was the logic of Benjamin Flores’ argumentation to convince Minas Gerais state and Brazilian governments to invest in his school project?

The understanding outlined around these questions was driven by the following aim: to grasp historically and interpretatively conditions and actions in connection with subsidies granting to Benjamin Flores’s school for women. The study derived from such proposition belongs to the field of history of education in general and of history of schooling institutions in particular, above all of relations between the public and the private. Historical sources to develop the research underlying this work included newspapers and magazines articles, manuscript and typewritten texts containing school bookkeeping (administration reports, state inspection notes and others), and photographs. These sources had a crossed reading so that to cover any gap in a given primary document regarding a given topic. In fact, as for financing documents, there are written and printed records of numbers, demands and actions, among other examples. Nevertheless, the understanding of circumstances regarding the obtaining of public funds stemmed from a more interpretive reading of the whole of the sources combined with the contextual elements.

The construction of such analysis according to the historical records read with interpretative intentions fits analytical categories such as vocational education, politics, and poverty in Brazilian first Republic (1889-1929). Urban context relates to how the city reacted through the political discourse and concrete actions to institute vocational education as a “government tool” to deal with the so-called poor population. It relates to conjunctions and disjunctions, agreements and conflicts as to the state and federal government participation in vocational education as a measure of modernization of a capital seen as a republican model of city. Understanding political discourse and concrete actions as the creation of schools to train professionals under approval of federal and state government makes possible to grasp how Belo Horizonte reacted to both the modernization process and the Republican ideal; how relations between (vocational) education funded by federal government and poverty (then a strong feature in social reality) were.

This work presents the context of the creation of Benjamin Flores’ school for women in Belo Horizonte. A federal decree is the starting point of such contextualization, which includes movements regarding vocational education (congresses and creation of schools), the making of Belo Horizonte society and the creation and functioning of a school for women. Besides, it presents an understanding of the public funds grant by Minas Gerais state in view of Benjamin Flores’ relations with government and Belo Horizonte society. We sought to understand who he was in that context aiming to outline the points he may have gathered and expressed to plead - and to get - funding for his educational cause.

The federal decree: study as a life struggle

On September 23, 1909, the newly elected president of the recent Brazilian Republic, Nilo Peçanha, signed the decree 7,566. By doing so, he validated the law 1,606 of December 29, 1906, which ruled elementary education as vocational education too. The decree allowed creating in capitals the artisan apprentice schools as public elementary and vocational education (FONSECA, 1986). At first, it appeared nineteen schools of such type in Brazilian states. They would operate under the ruling of Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs.4

In a report submitted to the National Congress in 1909, the president Nilo Peçanha stated the decree’s motivations and purposes. The urban population increase had required giving “working classes the means of overcoming the ever increasing life hardships”. The chosen way to do so was to “enable poor children with the indispensable technical and intellectual preparation”, as much as to make them “develop habits of fruitful work”. This way, one could make them leave the “illiterate idleness” and deviate from “vice and crime”. To Nilo Peçanha, “educating citizens to be helpful to the Nation” was a primary duty in Brazilian government (BRASIL, 1909).

The federal decree number 7.566/1909 echoed in Minas Gerais state. As Chamon and Goodwin Júnior (2012, p. 329-30) says, in Belo Horizonte, the “project of schooling working classes and the installation of a vocational school by the federal government amplified a process that intended to be the feature of the city, being present since its early days”. The first concrete action to fulfill the decree was creating the capital’s School of Artisan Apprentices, on September 8, 1910. At the same time, theses on vocational education were presented in congresses, amidst the ones by Cipriano de Carvalho on elementary schooling. As to vocational education, theses were on the convenience of manual work training in secondary schools as well as of vocational (agricultural, industrial, and commercial) and teaching education (with the addition of subject matters).

Studying to help oneself and the homeland: Belo Horizonte’s school for women

Participants of the congress in Belo Horizonte mentioned women’s education in their theses (“vocational education”). Underlying the discussion on the subject was the idea that school for women had to worry about students’ morals, profession, body and behavior to achieve the “perfect education”. The school for women followed trends of nineteenth-century European countries where women’s education meant training for work. According to Souza (2001, p. 113), professional preparation should enable them to “afford themselves”, because “not all them would marry” or would have “family financial support” forever. For the poor and single woman, vocational education would be an important way to live a life in minimally favorable conditions. Married women would work to free themselves from marital dependence and humiliation; they would raise their children, “uplift their husbands and watch over home ruling and economy.” That is why it was important to learn “the basics of Home Economics”: women could “satisfactorily take advantage of the husband’s salary by not wasting it.” Women trained to apply certain procedures more rationally would be able to save money by dealing with “financial resources of the family” according to an economic-mathematical logic. In so doing, they would “avoid [...] riots, political struggles, strikes of workers dissatisfied with low wages.” In a word, their work was a way to help building “the country’s wealth and well-being.” 5

To Gomes and Chamon (2010, p. 3), vocational education is connected to a republican discourse to legitimize the new government regime, which meant the republicans ability to “lead the Brazilian nation to a promising future through the paths of progress.” Such a regime would accept women within the professional circle and the labor market in a capital seen as representative of Brazil’s modernity (Minas Gerais modernity). As those authors put it, since the early city planning with a focus on civilization and progress, Belo Horizonte was meant to be a modern city. Therefore, the city was supposed to expect a new scenario, while society had to constitute new spaces and new social, commercial, cultural, and educational practices to be part of the new model of society and citizen in progress.

The initiative of creating a vocational school for women arose in this scenario. As Gomes and Chamon (2010) think, vocational education, in particular at Benjamin Flores’s school for women, meant a blow of modernity winds, of new sensibilities to be placed within the discourse of a city aimed to stand out as a capital. The school was central to make women able to earn the right to schooling; it was relevant to Belo Horizonte ideal of being the republican capital, where democracy would be the very guideline of the polis. If professional education materialized the republican discourse (the idea of a promising future via progress and modernization), then the foundation of a school for women in the newly created capital of Minas Gerais would be an example to the country: of a new time, of a new possibility of existence, the one the Republic instituted.

As a type of “urban imaginary Leitmotiv”, the idea of progress led to “perspectives of the future Minas Gerais capital, in its different and even conflicting extractions,” as Julião (2011, p. 118) said. Some saw it as the security of the progress: it offered conditions to “domesticate nature and turn it into a utilitarian source.” The production of “results for the state commonwealth would be greater, boosting industries, railway, the creation of agricultural, professional and other establishments that would have repercussions in all areas of the State” if the capital were elsewhere “than Ouro Preto”. Others saw in the capital a reinforcement of prosperity evidence, due to its “commercial, industrial and artistic development”.

In a modern republican city such as Belo Horizonte, women could rely upon a social development place that went beyond elementary and secondary regular public schools, since it reached other modernization process instances in the new capital. This thought echoes Gomes and Chamon (2010) idea that school for women sought to “build the representation of teaching in articulated connection with modern values in a modern city”, of “a modern teaching method suitable for capitalist industrial society”, in tune with the “symbol city of republican modernity”. As the authors say,

It would not be an exaggeration to say [...] that, in certain sense, it is the product of the coming of new sensibilities. It seeks to reflect the modern in a modern city. It is a way of integrating into the discourse, of building from it, even if its practices are still rooted in old habits. In a way, it is undeniable that it represents a will for change as to the place of women in society. On the other hand, it also shows how this was a difficult step to take (GOMES; CHAMON, 2010, p. 5).

This quotation allows inferring that Benjamin Flores had a modernization spirit. His school for women was an example of what had been denied to Brazilian women, especially the poor ones. Minas Geraes newspaper presented it in 1920 as it follows:

founded in August 1919, as stated in Minas Gerais newspaper of that month and year: The “Escola Professional Feminina, based in Belo Horizonte, is a technical and vocational educational institution, with indefinite duration and aimed to prepare its students by teaching them solid knowledge of an art or profession, so as to make them helpful in the struggle for life, useful to themselves and the homeland” (MINAS GERAES , Jan. 23, 1920, p. 4; our italics).

As said, the date of creation of the school seems uncertain, because it was necessary to rely on a 1919 newspaper edition. At the same time, the newspaper sets the creation of the school aligned in Nilo Peçanha speech that the school would, it should be noted, educate “helpful citizens to the nation”. Indeed, the school founder, Benjamin Flores, established the foundation of his school in 1919 too. An accountability report of his school for women submitted to Minas Gerais’ Public Security Secretary informs the following: “In operation since 1919, with legal personality, the Escola Profissional school is patriotically fulfilling the task it took on itself as to open new horizons to women’s activity and to preparing city young girls to work on behalf of the for the aggrandizing” (ESCOLA PROFISSIONAL FEMININA/EPF, 1928, p. 1; our italics). The caveat expressed in the term with legal personality allows us to infer that the school had operated without such status, that is to say, not only without the federal and state seal, but also without legal formalities

This possibility converges to sources recording the origins of Escola Profissional Feminina existence and gathered up to now. In March 1913, a newspaper in São Paulo city reported the return of “Mrs. Alexandrina de Santa Cecilia, teacher of Work at the Teaching School of Belo Horizonte, and Alice Horta, student of the third year at the school. [...] Mrs. Alexandrina told us that it would be soon installed and celebrated in the capital of Minas Gerais a vocational school [for women] similar, as much as possible, to the one in São Paulo’s capital (CORREIO PAULISTANO, March 1913, p. 3). Still in the 1950s, it was mentioned the year 1913. In Barreto (1950, p. 217), one may read the following: “teacher Benjamin Flores founded the Escola Profissional Feminina and in 1920 he managed to have legal authorization for the school certification” (our italics). Belo Horizonte’s 1953 Yearbook (BELO HORIZONTE, 1953, p. 151) quotes Barreto, but adds a year: “In 1913 teacher Benjamin Flores founded the Escola Profissional Feminina and in 1920 he managed to have legal authorization for the certification of his school.”

The possible certainty around 1913 as the year Benjamin Flores created his vocational school for women is dissipated by information in a report addressed to the President of Brazil by minister, Miguel Calmon du Pin and Almeida (1925, p. 640), from Ministry for Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs. As the ministry was the one from where it came funds to finance school for women in Belo Horizonte, such information is supposed to be based on documents submitted by the school to obtain granting. The report says the school was “Founded in 1917” and that it had its “certificates recognized by State of Minas Gerais government.”

Nevertheless, records of the school existence are more abundant from 1919 to the 1960s, when its activities ceased. It was the subject of a Minas Geraes newspaper article from January 1920 on topics like curriculum, school terms, and teachers above all. In this regard, it is as if the school for women history had begun, precisely, when Minas Gerais state recognized the legitimacy of the school’s certification, therefore, of the institution as well (GOMES; CHAMON, 2010). The following table displays information on how long such recognition lasted.

Table 1 Public funds aimed at Escola Profissional Feminina at Belo Horizonte city, 1919-45

| information source | date | funding | funding origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correio da Manhã newspaper | Sept. 16, 1919 | 10:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce |

| O Paiz newspaper | Aug. 8, 1922 | 7:500$000 | Public Expenses Board of Directors |

| Report of Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs | 1923 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| O Paiz newspaper | Feb. 2, 1923 | 220:000$000 | Public Expenses Board of Directors |

| O Jornal newspaper | Feb. 2, 1923 | 220:000$000 | Public Expenses Board of Directors |

| O Brasil newspaper | Dez 4, 1923 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| Report of Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs | 1924 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| O Jornal newspaper | Feb. 2, 1924 | 12:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce |

| Correio Paulistano newspaper | Feb. 2, 1924 | 12:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce |

| O Paiz newspaper | Nov. 23, 1924 | 12:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| O Paiz newspaper | Dec. 12, 1925 | 12:000$000 | Ministry do Tribunal de Contas |

| Report of Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs | 1926 | 12:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| Correio da Manhã newspaper | Dec. 12, 1926 | 12:000$000 | Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs |

| Report of Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs | 1928 | 13:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs |

| O Paiz newspaper | Sept. 17, 1928 | 25:000$000 | Minister of Justice |

| Jornal do Commercio newspaper | Sept. 17, 1928 | 25:000$000 | Minister of Justice |

| A Manhã newspaper | Nov. 30, 1928 | 10:000$000 | Minister of Agriculture |

| Report of Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs | 1929 | 10:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs |

| O Paiz newspaper | Nov. 24, 1929 | 10:000$000 | Minister of Agriculture |

| O Jornal newspaper | Nov. 24, 1929 | 10:000$000 | Ministry of Agriculture |

| O Paiz newspaper | Dez. 2 and 3, 1929 | 25:000$000 | Account Court House |

| Jornal do Commercio newspaper | Sept. 28 and 29, 1930 | 25:000$000 | Minister of Justice |

| O Jornal newspaper | Jan. 16, 1931 | 10:000$000 | Ministry of Education and Public Health |

| Jornal do Commercio newspaper | Jan. 16, 1931 | 10:000$000 | Ministry of Education and Public Health |

| O Jornal newspaper | Dec. 29, 1931 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice |

| Correio da Manhã newspaper | Dec. 29, 1931 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice |

| Diario de Notícias newspaper | Dec. 29, 1931 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Justice |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1937 | 20:000$000 | Ministry of Finance |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1939 | 15:000$000 | Ministry of Finance |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1941 | 6:000$000 | Ministry of Finance |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1943 | 5.000,00 | Ministry of Finance |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1944 | 5.000,00 | Ministry of Finance |

| Union Overall Balance Sheet - Ministry of Finance | 1945 | 10.000,00 | Ministry of Finance |

Source: indicated in the first table column

Judging by the numbers and dates in the table above (on public funds grant to the school for women), subventions were granted until 1945. It was not possible to locate records indicating that the grant continued after 1945. It is important to say Benjamin Flores managed to keep funds coming even at the time of budgetary cuts made by Olegário Maciel’s government policy (after all, the school already had funds coming from Brazilian government).6 In this regard, the following figure seems to converge to this fund granting: a photograph presented as a tribute to the rise of Olegário Maciel, an image made exclusively for the occasion.

The overall body position (sitting and standing), the contained gestures (hands resting on the lap, arms resting along the torso, feet and legs joined) and the solemn expression (serious countenance) of the students of Benjamin Flores’ school for women suggest the importance of the photography as a tribute. At the same time, their clothes seem to remind of military clothing, especially the blouse, which converges to the circumstances of military conflicts at that moment. Source: Minas Gerais Public Archive.

Figure 1 Students from Escola Profissional Feminina of Belo Horizonte city, November 1930

The public financial support aimed at the Escola Profissional Feminina was granted in a context of reorganization of primary education in Minas Gerais. In 1920, the article 9 of the state law 800 focused on the appointment of teachers profile for the elementary school: single female teachers or widows without children would be preferred. Benjamin Flores mentioned this preference in a school report submitted to Minas Gerais government, as one reads:

Despite the school enrollment fee being excessively inexpensive, its board makes it free to many students who are daughters of poor widowers and of parents lacking resources. Some of them are provided by the school with books and other class material (EPF, 1929, rel., p. 1).

Indeed, enrollment numbers deserve some consideration. In a report of the school activities in 1928, the number of regular students amounted to 150; in 1929, to 197. Given these numbers, a dilemma arises as to information contained in the report by minister Miguel Calmon du Pin and Almeida (1925, p. 640) abovementioned. This document states that, “Since the foundation, 823 students enrolled in the school.” To state more than eight hundred students after six years of public subvention granting was to think of an annual average of 130 students (a number relatively close to the average of the late 1920s) and just when the received funds still were not considered enough (“Income is a little more than 20 contos de réis”). If it seems questionable to state an average of 130 new enrollments each year since 1919, than it would be more acceptable if the sum of 823 students dated back to pre-1919 enrollments. If so, then this means the school already operated before it began to receive public funds and, thus, to start its “official history”. This possibility grows stronger if one considers a caveat made in the reading process of a manuscript document on the request for funds made by Benjamin Flores. In the text, a certain “R. Lopes” notes, on September 1, 1929, that “The school counts 6,242 days of hospitalizations, I mean, care” (MINAS GERAIS, 1929; underline in the original). Despite the copyist vocabulary miswriting, it is important to think about the numbers. In a simple calculation, such a number of days adds up to more than seventeen years. If so, then Benjamin Flores may have founded his school for women in 1913; and from that year until 1919, it may have operated without the legal personality status, that is to say, with certain anonymity, certain discretion that did not attract press attention.

Minister Calmon (1925, p. 640) recognized that the school income was small if compared to its “somewhat larger expenditure”. Hence, the school’s “rather modest” conditions. Yet it “provides good services to society.” Over the years, the income expanded. State records of the granting process for the 1928-30 span show the grant amount reached more than 33 contos of réis, including federal and state funds (EPF, 1928); but, even with increase in the funding value for the school, it was not enough to change physical facilities. The school’s 1928 report mentioned its building. The expectation was to have a “larger building” to try and “inaugurate new courses of arts and professions suitable for women and of more remunerative specialties”; of course, it would “depend on our resources” (EPF, 1929, p. 1).

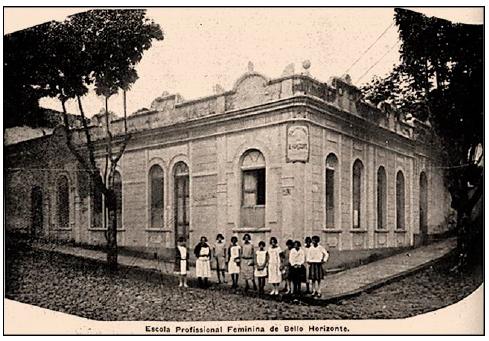

Indeed, “Appropriate facilities to classes and workshops” were seen as a central condition for the “good teaching result”, alongside a “well-oriented study program”, teachers’ “competence and attendance” and the “indispensable studying material”. As the school was “operating within a private and inadequate building [see figure 2] for the functioning of the vocational institute, our efforts aim at a new building - whether by constructing it or by acquiring it - that fully satisfies its purposes” (EPF, 1929, p. 5).

The building rented to house the school for women in of Belo Horizonte city between 1919 and 1933 was on the corner of Sergipe Street with Tymbiras Street. Renting was the second highest expense of the school. The external appearance suggests limited room for school activities, especially in workshop activities; the small number of students appearing in the photograph seems to reinforce physical space the limitations. Source: FonFon (1925, p. 46)

Figura 2 Building in Belo Horizonte city where Escola Profissional Feminina operated from 1919 to 1933

Besides being inadequate pedagogically and didactically for classrooms and teaching work, the school building required limiting its enrollment capacity. In 1928, a school report informed that enrollment number of new students had reached “one hundred and fifty-two” in various courses, so that “the school board had to refuse some enrollment applications.” It was “not only because the building where school currently operates is cramped, but also because high numbers of enrollment are harmful to students’ hygiene, discipline, and development” (EPF, 1928, p. 1). Between expanding enrollment budget with opening of more vacancies and compromising the schooling life of regular students with conditions inappropriate to study, it was preferable to accept the physical limitations of the school. It was not worth taking the risk of losing Belo Horizonte society recognition, since people had trusted in Benjamin Flores’ educational project.

Dynamics of public funds granting and implementation

Historical sources considered in this study covers the period from August 1928 to September 1930. Information they contain is on subventions granted by Minas Gerais state to the school for women. That is why such documents offer little as to understand the relationship with federal government in this regard. Despite that, it is possible to project the subvention granting dynamics. Once approved, the process had its documentation scrutinized: what characterized the school and its proposal, its actions and its personnel, expenses and forms of resource use, among other points. In this sense, sources considered to develop this study make possible to see how was the granting of public funds, especially the state government’s, whose subvention the school received every six months.

Indeed, documents lacking pieces were likely to stop the fund grant process; in other words, the release of public funds depended necessarily on showing certain documents: school actions report, expenses description and resources use proof. Judging by the communication of the school with Minas Gerais government authorities, gathering and presenting proofs of public funds spending was a key requirement for the state, to the point of stopping the release of resources. Consequently, in cases where of subsidy withholding, meaning non-payment to the school, the delay resulted in further delay for the school as to obtain and submit documents; in particular, documental proof of public funds spent in favor of the school for women. This understanding draws from formal requests written in his own hand by Benjamin Flores addressing the government as an attempt to release subsidies. For example, on August 7, 1928, Benjamin Flores signed a formal request addressed to the “Secretary of Security and Public Assistance”. Part of what he was asking for is the following:

This document assignee, from the board of Escola Profissional Feminina [vocational school for women], comes to request the grant payment to which the school is entitled and referring to the second semester of the current year [1928] ex-vi of current budget provision. This request asks permission to present in due time documents proving the use of granted resource, since the school still did not received either the amount referring to the last year, nor that of the first semester of this year (FLORES, 1928; underline in the original).

Apparently, the school did not receive state funds for a year and a half. Subventions transferring only happened in August 1929, as one may infer from the following formal request:

The Escola Profissional Feminina [vocational school for women] of Belo Horizonte, represented by its principal - this document assignee -, comes to request the payment of public funds to which the school is entitled relatively to the first half of the current year [1929]. With an enrollment of 197 students in the current schooling year, the school keeps 38 students who do not pay for studying [...]. Having received subventions referring to last year’s second semester at the end of last July, the school asks permission to submit in due time documents proving the spending of funds received lately - 1.782$000 (FLORES, 1929; underline in the original).

Although the school for women received public funds as for 1927, the first subvention of 1928, to be paid in July, rested unpaid just when enrollment had been higher (197 students). The situation forced Benjamin Flores to ask for the release of funds because the non-fulfillment of gaps in the documentation stemmed from delay even in the receiving of subsidies. On September 3, the secretary replied to a new Benjamin Flores formal request. According to the reply, the school’s request would be assessed, as one may infer from the following: “the secretary thinks that, according to the prosecutor reply, the institution, having no equity income” and having “its ordinary income […] all spent in the institution maintenance it” and no cash on hand, then the school could perhaps be allowed to present required document at another time [...] To consideration.” On December 14, the “amount of 3:497$520” (MINAS GERAIS, 1929) was approved.

Part of the dynamics of granting Escola Profissional Feminina with state subsidies may be characterized minimally by sources considered in this study. In this regard, the process - one should stress - required the submission of a report on the school’s actions and funds spending. Once the report had the government approved, a state authority paid a visit to the school to inspect and inform his considerations in a visiting note.

The school report had a more or less predefined structure. The contents went from the presentation of the school to the certificates; it presented information on enrollment (including on free ones), courses, showcase of works, exams, completion, teachers, schedules, attendance, teaching material, revenue/expense and annexes (subjects description and balance sheet), subjects taught, among others. The main element for approval and referrals was the description of revenue and, above all, of the expenditure. The following table displays numbers for this part of the reports.

Table 2 Revenue and expenditure of Escola Profissional Feminina in Belo Horizonte city, 1928

| 1928 | |

|---|---|

| Revenue | Amount |

| Federal subsidy (net value) | 22:500$000 |

| State subsidy (first semester apportionment) | 2:814$830 |

| Student enrolment fee | 7:350$000 |

| Verified deficit | 605$970 |

| Expenditure | |

| Building rental | 8:400$000 |

| Sum paid to printing services (newsletters, receipts, booklets, etc.) | 755$000 |

| Sum paid to Casa Pratt for the fixing of 14 typewriters | 450$000 |

| Sum paid to Casa Pratt for a typewriter | 550$000 |

| Building fixing and cleaning | 450$000 |

| Classroom chairs, cabinets, and tables fixing | 397$000 |

| Sum paid to Dias Cardoso for secretary work material, chalk, paper, ink, books etc. | 248$000 |

| Salary payment for teachers and other employees, 1928 | 22:000$000 |

| 1929 | |

| Revenue | |

| Federal subvention as for first semester | 12:000$000 |

| Enrollment fee for first semester | 3:730$000 |

| State subvention (first semester apportionment) | 1:782830 |

| Deficit | 138$000 |

| Expenditure | |

| Building rent | 4:200$000 |

| Paid to Casa Pratt for the fixing of 14 typewriters | 450$000 |

| Bonus to teachers and other employees | 13:000$000 |

Source: EPF (1928; 1929)

Although there was an increase in revenue, Benjamin Flores saw the school resources as scarce: due to the “scarce resources available, we have a modest teaching material” (EPF, 1929, p. 5). The same regard had the prosecutor Antônio Leal Costa, responsible for inspecting the Escola Profissional Feminina on Minas Gerais state behalf. His 1929 visiting note said this “The strain of resources within which he [Benjamin Flores] has to put his welcomed school project is relieved by the right guidance in administration and the devotement of its teachers, who are specifically educated and efficient.” For the prosecutor, the school “fully fulfills the aims for which it was created” (COSTA, 1929).

Even if the school had modest facilities, it cannot be said such condition prevented it of developing school activities and the institutional functioning. This statement draws on inspection and visiting notes written by the prosecutor-school inspector. In general, the inspection took place after the submission of school documents to the government; it is as if the biannual reports were the basis for guiding the visit. The handwritten version of the 1929 visiting note reveals a complimentary tone:

I attest that I visited the Escola Profissional Feminina [vocational school for women], which operates with high attendance [...] the school’s expenses are in proportion to the relevant services provided to youth [...] and [I attest] that there was no lapse in the subvention spending by the school administration in (COSTA, 1929).

This recognition of Benjamin Flores’ school developments reappears in a visiting note of June 1929. As the school inspector wrote, “From my inspection, I think that the Escola Profissional Feminina [vocational school for women] [...] is providing the state and society extremely relevant services with, because it is preparing efficient workers for the elevation of our homeland, which should expected all from tomorrow’s youth” (COSTA, 1929).

Interestingly, this June visiting note refers to Benjamin Flores’ school as it follows: “it has been operating in this capital for almost ten years now, with a high number of students.” It allows questioning the date when the school appeared. In this case, it is appropriate to think of the possibility in which a private school managed to rely on public funds in the same year it was created (COSTA, 1929).

In 1910, it should be stressed, Minas Gerais government created a vocational school in Belo Horizonte. In addition, other city’s public institutions demanded state funds too. Thus, it is surprising that Benjamin Flores had managed to persuade the state government to fun partially his project of a vocational school for women in Belo Horizonte. One guideline to understand his achievement is to think that he had gathered and combined personal attributes that backed him and his projects up. In this case, such attributes would have sufficed to Belo Horizonte society, as to support his school project by enrolling girls, and to the government, as to bet on the project as an important measure for the city by funding it. The question is of focus on a practical measure: that of setting up and running a school at the turn of 1919 to 1920. After all, judging by table 1, October 1919 seems to have been the date the funds granting began.

Benjamin Flores’ vocational school

Benjamin Flores’ direct communication with government authorities highlights his central position at the Escola Profissional Feminina: he was the one responsible for it. The pedagogical and administrative activity in the school was subjected to his scrutiny, as one may infer from comparative reading he used to make between manuscripts and their typed copies to revise them. This position places him as the one who would have to obtain subsidy for his school by interacting personally with federal and state government representatives. In possible meetings with government people, he probably showed in detail his project of a school for women to train them as professionals who would help to aggrandize the homeland; and he possibly did it with great confidence in his ideal, for he was successful. If so, then one might think Benjamin Flores’ confidence had roots in him as a Belo Horizonte citizen since the city early days. Between late 1890s and late 1920s, he was able to establish himself and project himself among public authorities as someone remarkable for his abilities and actions, much more than for his attributes of political or financial elitism, for example.

Ribeiro e Silva (2018) wrote about Benjamin Flores life. Their study helps outlining his social position in Belo Horizonte because it exposes a background full of clues of him as citizen, father, teacher, public agent, council member, and school owner; above all, it deals with his involvement in problems of the working class such as housing and housing surrounding conditions. It was common then children death due to unhealthiness in neighborhoods inhabited by the working class. He knew these problems closely because he bought a house in one of these neighborhoods that developed along with the city. His relationship with working class people was such that they elected him to chair neighborhood associations.

According to Ribeiro e Silva (2018) study, the civil servant Benjamin Flores working at Ouro Preto city post office at the end of the nineteenth century became the owner of a school for women in Belo Horizonte. As civil servant, he managed to conciliate his work as a copyist with teaching in several schools, whether in Ouro Preto city or Belo Horizonte. The fact that he graduated in the traditional Colégio do Caraça high school gave him a lot of credibility as a teacher. Once established in Belo Horizonte, he applied for a vacancy in the city council. In 1903, his name appears as an alternate director; in 1904, as a council member, position he kept until 1919 (cf. SILVEIRA NETO, 1981). In the meantime, he articulated actions and projects, such as that of remunerating the city council members - disapproved (RIBEIRO; SILVA, 2018) - and constructing a building for the city council - approved.

On September 6, 1914, the Municipal Council Palace was inaugurated. The opening event was attended by Bueno Brandão, then Minas Gerais governor, and Belo Horizonte former mayor, Olinto Meireles, and his substitute, Cornélio Vaz de Melo. The city council chairman, Levino Lopes, stressed Benjamin Flores work, as it reads in Silveira Neto (1981, p. 294-5),

The initiative of building this place has nothing to do with me; but I did use to think it was a shame a city council without a place of its own. I grew sad when answering those who asked me “where [is] the Municipal Palace?” that we did not have it. It was the same as saying “There is no aldermen in the city; your government is not constituted”. This initiative is up to our colleague, Mr. Flores, who proposed it - if I recall - and managed to see the necessary funds for the building acquisition or construction included in the city budget, which would not be possible without the former mayor goodwill. After all, laws worth nothing if not fulfilled (Minas Gerais, 29-9-1914).

As it reads, the presence of Benjamin Flores in Belo Horizonte’s city council placed him alongside state and municipal authorities as mayors and governors. In other words, authorities of high position in Minas Gerais the political hierarchy accompanied his projects.

In the meantime, he had worked as teacher, alderman, and school manager, besides helping thinking of education in Minas Gerais by taking part in education congresses. Due to a multifaceted action in Belo Horizonte society, Benjamin Flores was a constant and remarkable presence within the city. His social penetration crossed social strata: from the working class to the political elite, from the popular neighborhoods to the instances of the state government (city council). His circulation situated him in places of varied sociability: from the workplace as copyist to classrooms as teacher and to secretary rooms as school manager, from public administration places and offices to events attended by intellectuals, whether congresses or a bookstore inauguration (RIBEIRO; SILVA, 2018).7

Before joining the city council, in 1899 Benjamin Flores had become Latin teacher at Ginásio Mineiro school and joined the Superior Council of Public Education, chaired by Delfim Moreira, secretary of the Interior. Then, he was appointed by the ministry of Justice and Interior Affairs to oversee school exams and was chosen by federal government to evaluate and report the Academy of Commerce situation. At Ginásio Mineiro, he went beyond teaching by forming a group of teachers to find ways out with the help of the rector. Even teaching at Ginásio Mineiro and working in the city council, Benjamin Flores was able to teach in other schools and even to found schools. In 1912, alongside two people, including a senator, he created the School of Commerce. Two years later, he joined other enthusiasts to create the School of Agronomy and Veterinary (OLIVEIRA; SILVA, 2018).

Benjamin Flores left the council in 1919, just as he began receiving state subsidies on his behalf - it is likely his staying was incompatible. At the same time, with the public recognition, his school would expand attendance capacity, that is to say, the amount of work to do. After all, enrollment in 1929 was higher in almost 50 students compared to 1928’s. Therefore, school administration and teaching would require much more dedication (time, attention, concentration, disposition, etc.).

That said, in wanting and obtaining public subsidy for the Escola Profissional Feminina, Benjamin Flores gathered important attributes as knowledge on education (elementary, secondary and higher), on school management, and on public administration (budget and municipality demands). Besides, he created a network of political relations at the municipal, state and federal levels; as city advisor, he established bonds with politicians like Fidélis Reis, a key name in the vocational education in Minas Gerais (RIBEIRO; SILVA, 2018). Above all, Benjamin Flores knew the profile of the population and its demands, so he was able to glimpse the including of part of the population in the development process of Belo Horizonte. His multifaceted presence in the capital society projected him amid conditions, circumstances and facts that backed him up with positive attributes to his person - his behavior - and to the acceptance of his projects for the city.

One final attribute Benjamin Flores may have used in favor of subvention grant would be his school for women itself. Indeed, if the date of 1913 (or even 1917) is correct as the year of creation of his school for women, then it is worth thinking that he may have presented concrete results to the government: students’ names, teaching program, and plans to expand the school, building, facilities and others. He would have pleaded for subsidies with the confidence of someone aware of what he wanted and needed, precisely, because of the practice, which would have led him to perceive the modernization process (and desire) within the (society of the) capital of Minas Gerais and work so that population could see it clearly.

If it is correct to say Benjamin Flores was able to sustain his school for a minimum of time without public subsidy, then one might think society had reacted together with him to the modernization process. The biggest proof of this reaction would be the grant of state funding to the school. It is as if the educational project of the school converged to society expectations, especially the elite that was forming and with what Benjamin Flores related as a public agent and teacher. Therefore, for society, it was justifiable to approve the inclusion of his private school in the apportionment of state resources grant to public institutions (such as the city council itself, whose head office was constituted with municipal funding, it is worth remembering). Although the school for woman was private (Benjamin Flores’ and his family’s “business”), its purposes were in line with intentions attributed to vocational education by Brazilian government; besides, Benjamin Flores was attentive to the debate on (the problems of) education in Brazil as an intellectual, as an active teacher and as a public agent able to propose solutions. Not by chance, the presence of references to the homeland and patriotism mark discourses associated with the school, in its characterization in newspaper or in the assessment of authorities who inspected it. Benjamin Flores’s private school seemed to be taken as a public school oriented towards patriotism.

Final remarks

As historical writing depends above all on evidence (sources, documents, vestiges, etc.), history continues as long as sources appear. This means the writing of history (of education) does cease. At least to us, the possibility of making this study is a proof of this inexhaustible doing. As an academic work, this article belongs to a larger research that dealt only superficially with themes discussed here because there were not enough sources. Thanks to the discovery, in 2018, of more documents, it was possible to broaden the historical understanding of vocational education in Minas Gerais, subject of previous studies.

Sources considered in this study instigated a revision of the date of creation of Escola Profissional Feminina in Belo Horizonte city, which was a vocational school for women. They suggests the official date of 1919 cannot be considered without questioning, that is, the year of foundation cannot be taken as the year of recognition of the school certification and subsidy granting. The right date of creation is important because Benjamin Flores’ school - and attitude - may be seen as a milestone in the modernization process of Minas Gerais attributed to the construction of Belo Horizonte. In this model capital, it was necessary to ensure means for women to leave their traditional condition of restriction and submission and to enter the modern condition of freedom and autonomy. While the opinion of “inspectors” in visiting note stressed this role of the school, Benjamin Flores’s concern with the poor was noted in his communication with the state as a factor that highlighted his school. In this sense, if it is correct to say the school appeared, in fact, in 1913, then one may see in the presence of Benjamin Flores in the 1912 congress of education a starting point to go from discourse to practice; more than that, one may recognize his vision of the future, recognize him as ahead of his time.

Indeed, the population and institutions of Belo Horizonte in the first decades of the capital aligned themselves in the agenda of progress and modernization that would guide the republican government project and modify political life at its most local levels. Belo Horizonte society reacted to the input to meet demands that can be derived and associable to school and poverty. Society assimilated the relationship between education and poverty and elaborated it through its public agents. Thus, if there was an educational movement for vocational education (see the decree of 1909), then Belo Horizonte’s reaction was to bet on initiatives oriented to such movement and to be ready to meet modernization demands and enforce the republican ideal.

This paper is an initial approach of newly found sources (records of relations between the school for women and the state regarding subsidies granting). The potential of manuscripts and typing is enormous. Its content opens to the understanding, for example, the public agents involved (see the prosecutor as inspector), the correlation between grant money and its spending by the school, the relationship between increased enrollment and increased subsidies, among other numerous analysis possibilities.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Miguel Calmon du Pin e. Relatórios do Ministério da Agricultura - apresentados ao presidente da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil pelo ministro de Estado da Agricultura, Industria e Comércio. 1925. [ Links ]

BARRETO, Abílio. Resumo histórico de Belo Horizonte - 1701-1947. Belo Horizonte: Imprensa Oficial, 1950. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Prefeitura. Anuário de Belo Horizonte, v. 1, ano 1. Belo Horizonte 1953. [ Links ]

BICCAS, Maurilane de Sousa. O impresso como estratégia e formação: Revista do Ensino de Minas Gerais (1924-1940). Belo Horizonte: Argvmentvm, 2008. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Decreto 7.566, de 23 de setembro de 1909. Crêa nas capitaes dos Estados da Republica Escolas de Aprendizes Artifices, para o ensino profissional primario e gratuito. Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1900-1909/decreto-7566-23-setembro-1909-525411-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em: 15 set. 2020. [ Links ]

CAJAZEIRO, Karime Gonçalves. A cidade jardim belo-horizontina e o campo do patrimônio cultural: representações, modernidade e modos de vida. 2010. Dissertação (mestrado em Ciências Sociais) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte. [ Links ]

CHAMON, Carla Simone; GOODWIN JÚNIOR, James William. A incorporação do proletariado à sociedade moderna: a Escola de Aprendizes Artífices de Minas Gerais (1910-1941). Varia hist., Belo Horizonte, v.28, n.47, p.319-40, jun. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-87752012000100015 [ Links ]

CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE INSTRUÇÃO PRIMÁRIA E SECUNDÁRIA, 2., 1912, Belo Horizonte. Anais... Belo Horizonte: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de Minas Gerais, 1912. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Claudia. Ser mulher, mãe e pobre. In DEL PRIORE, Mary. História das mulheres no Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto, 2013, p. 510-33. [ Links ]

GOMES, Warley A.; CHAMON, C. S. Entre o trabalho, a escola e o lar: o caso da Escola Profissional Feminina de Belo Horizonte. In: SEMINÁRIO NACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO PROFISSIONAL E TECNOLÓGICA, 2., Belo Horizonte, 2010. [ Links ]

JULIÃO, Letícia. Sensibilidades e representações urbanas na transferência da Capital de Minas Gerais. História, São Paulo, v. 30, n. 1, p. 114-47, jan./jun. 2011. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, B.O.L.; SILVA, E.F. “Na luta pela vida, uteis a si e á Pátria”: perfil biográfico-profissional do professor Benjamin Flores. Cadernos de História da Educação, v.18, n.3, p.621-39, nov. 2019. https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v18n3-2019-3 [ Links ]

ROCHA, Marlos Bessa Mendes da. A lei brasileira de ensino Rivadávia Corrêa (1911): paradoxo de um certo liberalismo. Educ. rev., Belo Horizonte, v. 28, n. 3, p. 219-39, set. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-46982012000300011 [ Links ]

SILVEIRA NETO. Conselho deliberativo. R. Inf. Legisl., Brasília, v. 18, n. 70, abr./jun. 1981, p. 294-5 [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rita de Cássia de. Sujeitos da educação e práticas disciplinares: uma leitura das reformas educacionais mineiras a partir da Revista do Ensino (1925-1930). 2001. 355 f. Dissertação (mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

CORREIO PAULISTANO. Lorena - instrucção publica mineira. São Paulo, SP, segunda-feira, 17 de março de 1913, ed. 17833, “Telegramas” [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DE MINAS. Inauguração da Livraria Alves. Belo Horizonte, 16 jun. 1910, s. p. In: MONIZ, Edmundo. Francisco Alves de Oliveira (livreiro e autor). 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: ABL, 2009, p. 114-6. [ Links ]

FON FON. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 16 de maio de 1925, ano XIX, n. 20. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAES. Belo Horizonte, MG, 23 de janeiro de 1920, ano XXIX, n. 19, “Seção alheia”. [ Links ]

REVISTA DE ENSINO. Conferência de Aprígio Almeida Gonzaga, sobre a - I Finalidade do trabalho manual para mulheres; II Finalidade do trabalho manual para os homens; III - Finalidade do trabalho manual na formação civica dos jovens. Belo Horizonte, MG, ano 1, n. 5, 14 de julho de 1925. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

COSTA, Antonio Leal. Cópia do termo de visita, lançado no livro pelo próprio punho do Dr. Promotor de Justiça. Datiloscrito, folha, assinada e conferida. Belo Horizonte, MG, 10 de junho de 1929. [ Links ]

COSTA, Antonio Leal. Termo de visita. Datiloscrito, 1 folha assinada e conferida. Belo Horizonte, 9 de março de 1929. [ Links ]

ESCOLA PROFISSIONAL FEMININA DE BELO HORIZONTE. Relatório referente ao anno de 1927. Datiloscrito, 9f., grampeado. Belo Horizonte, 31 de janeiro de 1928. [ Links ]

ESCOLA PROFISSIONAL FEMININA DE BELO HORIZONTE. Relatório referente ao anno de 1928. Datiloscrito, 9f., grampeado. Belo Horizonte, 31 de janeiro de 1929. [ Links ]

FLORES, Benjamin. [Exm. Ins. Dr. Secretário da Segurança e Assistencia Pública... requerimento]. Manuscrito, 1 folha. Belo Horizonte, 7 de agosto de 1928. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Secretaria de Segurança e Assistência Pública. 4ª seção. [Registro de tramitação e resolução de requerimento]. Manuscrito, 1 folha. Belo Horizonte, 3 de setembro de 1929. [ Links ]

2The first primary and secondary congress was in São Paulo state in 1911; the third one in Bahia in 1913; the fourth in Rio de Janeiro city in 1922.

3The research underlying this article stems from the research project called Educação, pobreza, política e marginalização: formação de trabalho na nova capital de Minas Gerais, 1909-1947, on education, poverty, politics, marginalization and the making of schooled-trained work force in Minas Gerais state capital. The project had the approval of FAPEMIG, Minas Gerais’ research support foundation, and of CNPq, Brazil’s national research council.

4In connection with the 1909 decree, there was the following context: the consolidation of the project was reinforced by the creation of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade Affairs. The inclusion of industry and commerce in the ministerial affairs was an economic measure that allows us to understand that, as a central guideline in a country, economy affects social life. For example, manufacture making and manufacture distribution would take place, respectively, in urban areas of low population density (industrial districts) and in areas of high population density (city central region and its neighborhoods) (FONSECA, 1986).

5Revista do Ensino, a magazine aimed at teachers, published the “Conference of Aprígio Almeida Gonzaga, on the - I) Purpose of manual work for women; II) Purpose of manual work for men; III) Purpose of manual work in the civic education of young people” (p. 119). It is worth to quote the view of this educator and director of vocational schools, one for men, the other for women’s in São Paulo state: “The subject of the school: to me, the purpose of vocational teaching of arts and crafts for women does not seem well oriented. The vocational school should be called: school of domestic and vocational education. I want a school that prepares the wife by giving her a profession, instead of a school that turns her into a worker in spite of her social mission. We leave aside this whole issue of rights, claims, and feminism. Let us meet nature, which, in the organization and organic differentiation of each person, established functions and adaptations to life. The vocational school [is] to me a great home and based on such view I will unfold my way of seeing to show this orientation opportunity and rightness.”

6The restrictive policy of Olegário Maciel’s government dissatisfied the education sector. As Biccas (2008, p. 67) says, “Changes arising from the post-revolution period have affected profoundly the educational guidelines coming from the education reform of 1927. Measures adopted in the provisional government eventually outlined what education would be in the state from then onwards. [...] In 1931, the Department of Education and Public Health, through numerous official acts, stopped teaching in 335 rural schools, in 112 urban schools, and in 26 night schools. Reasons for that were low attendance, low demand [...] and lack of available buildings.” The government extinguished rural schools and those with low attendance and demand. There was, of course, teacher unemployment, while families turned out to be the sole responsible as for educating their sons and daughters. Differently, the Escola Profissional Feminina — then having its certification officially recognized — continued to receive subsidies from the state government.

7“It was inaugurated yesterday, being then opened to the public attendance, an important commercial establishment, […]. Its worthy owners Mr. Francisco Alves & Comp., who owns the large and well-known bookstore established in Rio de Janeiro too, come to provide our capital with this new important bookstore as well as Minas Gerais state, where the lack of a large establishment of this kind was visible. The distinguished engineer Dr. Manoel Pacheco Leão, partner in the bookstore business and representative of that commercial firm, was kind enough to invite people from Belo Horizonte society to solemnize with his presence the auspicious event, grateful mainly to intellectuals and educationists, of the opening of a complete bookstore. [...] Among the people present at the act, we were able to take note of the following: [...] teacher Benjamin Flores” (DIÁRIO DE MINAS, 1910, s. p.).

Received: September 18, 2020; Accepted: December 10, 2020

text in

text in