Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.20 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Ene-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v20-2021-19

Articles

Body education at the João Alcântara School Group in Porteirinha/MG and its interface with the catholic Project1

1Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Northern Minas Gerais (Brazil). wilneyfernando@yahoo.com.br

2Federal University of Uberlândia (Brazil). armindo@ufu.br

The purpose of this article is to investigate the influence of the Catholic Church on the corporal practices of the João Alcântara School Group, in Porteirinha/MG, between the years of 1930 and 1945. For the Church, education was a powerful strategy with regard to the expansion and maintenance of it’s hegemony, and, through it’s doctrine, it proposed the bodily education of children, youth, and women so that they could add strength to religion. For the constitution of this task, the analysis of documentary sources was carried out in books of meetings of teachers, newspaper clippings, photographs, tombo books of several parishes and educational legislation. As a result, it can be said that the education of the body supported the education of mind and morals. As a result, sport became an interesting ally for a proposal of a State and a Church that claimed to be to be unitary, strong and fundamental within their domains.

Keywords: Education; Body; Catholic Church

A proposta deste artigo é investigar a influência da Igreja Católica nas práticas corporais do Grupo Escolar João Alcântara, em Porteirinha/MG, entre 1930 a 1945. Para a Igreja, a educação foi uma poderosa estratégia no que diz respeito à expansão e à manutenção da sua hegemonia, e, por meio da sua doutrina, ela propôs a educação corporal de crianças, jovens e mulheres para que pudessem somar forças à religião. Para a constituição dessa tarefa, foi realizada a análise de fontes documentais em livros de reuniões de professores, recortes de jornais, fotografias, livros do tombo de diversas paróquias e legislação educacional. Como resultado, pode-se afirmar que a educação do corpo dava suporte à educação da mente e da moral. Com isso, o esporte passou a ser um aliado interessante para uma proposta de um Estado e de uma Igreja que se diziam, dentro dos seus domínios, unitários, fortes e fundamentais.

Palavras-chave: Educação; Corpo; Igreja Católica

La propuesta de este artículo es investigar la influencia de la Iglesia Católica en las prácticas corporales del Grupo Escolar João Alcântara, en Porteirinha/MG, entre 1930 y 1945. Para la Iglesia, la educación fue una poderosa estrategia en lo que se refiere a la expansión y el mantenimiento su hegemonía, y por medio de su doctrina, propuso la educación corporal de niños, jóvenes y mujeres para que pudieran sumar fuerzas a la religión. Para la constitución de esta tarea, se realizó el análisis de fuentes documentales en libros de reuniones de profesores, recortes de periódicos, fotografías, libros de tombo de diversas parroquias y legislación educativa. Como resultado, se puede afirmar que la educación del cuerpo apoyaba a la educación de la mente y de la moral. Con eso, el deporte pasó a ser un aliado interesante para una propuesta de un Estado y de una Iglesia que se decía, dentro de sus dominios, unitarios, fuertes y fundamentales.

Palabras clave: Educación; Cuerpo; Iglesia Católica

Introduction

The present work, has as the main objective to investigate the influence of Catholic Church in bodily practices of a school group called João Alcantara, located in the city of Porteirinhas, in the north Minas Gerais, between the years of 1930 to 1945. The temporary cut coincides with the first fifteen years of the political emancipation of the city. With the creation of the school group and also with the installation of the local parish in the city of Porteirinha/MG, action that would bring the Church closer to the local government.

The text will be divided in three different parts: in the first one, we will introduce some official educational legislation of the period that marked out the purposes of teaching that dictated the formative and moralising tone for children, young people, men and women of that time. Upon entering the school institution, we will look into physical education, important obrigatory curricular component, that helped to shape the body, discipline it, making it strong and containing it, in short, this component was a big part of the political projectdesired for the Brazilian nation. The physical education supported the mind education and moral education. That way, the sanitized, civic and docilized body was prepared for a entire new way of sociability in wich the sports rules barred human momentum and natural instincts.

However, if the political component dictated the ways of education, the religious traced the way to walk. Therefore, we will show, in the second part of the work, how the manifestations of the sacred, the symbols and the catholic values were cultivated in that school group. In this space of actions, the ecclesiastical institution played a direct role in the way of people to see and be in the world. Finally we will understand, in this section, how it was made the main alliances between the church and the state. Finally, we will present the final considerations and references of the research.

For the accomplish of this task, a broad historical documentation was analyzed that presented practices, ampla, speeches, postures and experiences of the people of that time. In this way, we use documentary sources such as books of teacher meetings, local and regional newspapers clippings, school bulletins, tombo books from various parishes, laws and decrees of the executive branch, photographs and regional and national as well.

In the beginning of the decade of 1940, the city of Porteirinha had a population of about 20 thousand inhabitants (IBGE, 1947) wich desired an expansion of the primary school spaces. To fulfill this request, the city’s economic and social elite, through various political articulations with the state sphere, transformed the three mixed district schools into the João Alcântara school group (ESCOLA MISTA DO DISTRICTO DE PORTEIRINHA, 1929). The institution had as it’s objective to decrease the number of school-age children who were not recieving instruction2 and to educate this public within moral and catholic standards. Thus, created on June 30, 1937, by decree n. 885, published in the official gazette of Minas Gerais (MINAS GERAIS, 1937, p. 217) and installed months later, the school group, in its first year of operation, had 192 students, distributed in four classes, and four years later, had 420 registration (GRUPO ESCOLAR JOÃO ALCANTÂRA, 1946). The institution, that time, represented the biggest and was the main primary educational institution in the city.

It is important to register that, when we chose the place as a perspective of historical approach in the north of Minas Gerais, more specifically the city of Porteirinha and the João Alcântara School Group, we established a frontier where something began to be present: diverse sociabilities, in varied temporalities and territorialities, which began to gain forms portrayed by the school, the newspapers and the Church in this locality, immersed in transversality of the most diverse dimensions (political, educational, religious, cultural etc.). In these terms, the emphasis on local history is not opposed to global history, that is, “the cutout on local history only designates a more or less inclusive thematic delimitation according to the particularities to be determined, within the chosen social and temporal space” (CARVALHO; CARVALHO, 2010, p. 79).

Therefore, to understand the domains of the History of Education is to visualize them in a field of multiple dimensions, which shelters the regional, and this is inserted within a broader and more general spatial and temporal scenario, which dialogues with the proposals and discussions at the national and international levels. Thus, we do not propose to make a regional History of Education, but a Brazilian History of Education with emphasis on the regional.

Physical Education and Body Training in the School Group

Dialogue between teacher Olivia and her students:

- Mary, what does the body look like?

- It is similar to a plant because it grows.

- Mario, what is your opinion?

- I think it looks like an automobile, because it walks.

- And you, Jaime, what do you think?

- I think the body looks like a house because...

because we built it.

(REVISTA VIDA E SAÚDE, 1941, p. 16).

At the end of the 1930s, according to Lenharo’s studies (1986), numerous specialized magazines in health, hygiene, sports and physical education appeared. The body was the order of the day and the attention of doctors, politicians and teachers was on it. According to Schneider (2002), these vehicles of information made it possible to understand the discourse as a practice that assumed a place of power and, at the same time, a device for imposing knowledge and standardizing school and non-school practices. The circulation of magazines helped the propagation of new models, new body practices and the production of new habits.

In this sense, institutions such as the army, the churches and the school became aware that thinking about society in order to transform it necessarily involved treating the body as a resource for attaining the whole integrity of the human being. In the excerpt above, the dialogue between teacher and students explores comparative images of different perceptions of the body. The growing plant refers to the natural condition of the human body, a response that fits, in the text, a girl educated presumably to assume her role as a reproducer of bodies and, therefore, a more intimate knowledge of the natural movements of generation and growth. The automobile that walks reports to the domain of culture, at the level of the machined body, useful merchandise, radically shaped by human action itself. The body as a built house generates an image that superimposes itself on the others and puts emphasis on the moderate cultural and moral elaboration of the house-family. Both trails, which derive from the third image, will end up guiding the conduction of a pedagogical discourse, through which the teacher advises personal care with her own body and demonstrates the social repercussion of individually applied hygienic practices (LENHARO, 1986).

This pedagogical discourse sought to cultivate a beautiful, strong, healthy, hygienic, active, orderly and patriotic body, in contrast to the one considered ugly, weak, sick, dirty and lazy (VAGO, 1999). In schools, therefore, it was necessary to build the body of children and youth. In this context, the practice of Physical Education was an integral element of moral and civic formation, since it affirmed itself as an aspect of disciplining the bodies.

According to studies by Bercito and Novinsky (1991), during the 1930s and the first half of the 40s in Brazil, Physical Education was given the role of helping to build the Brazilian nation. This would be achieved by investing in the physical population as a whole in order to improve the Brazilian people physically and racially, making them strong, healthy and eugenized. At the same time, it would also be possible, from Physical Education, to introject values such as order, discipline, hierarchical respect, fighting spirit and obedience into individuals. The regeneration of society was projected as a resource to build a strong nation.

The Brazilian Constitution of 1937, promulgated by Getúlio Vargas, in its article 15, established the bases, determined the national education frameworks and outlined the guidelines to which “the physical3, intellectual and moral formation of childhood and youth” should obey. Article 131 established: “Physical education, civic education, and homework shall be obligatory in all primary, secondary, and high schools, and no school of any of these children may be authorized or recognized without meeting that requirement” (BRASIL, 1937, p. 12). The school curriculum served to support the national unity project.

Naturally, the official stance of the government was to support body practices4. Article 132 of this law ensured this:

The State will found institutions or give its help and protection to the foundations (referring to educational establishments) by civil associations, having one and the other in order to organize for the youth annual work periods in the fields and workshops, as well as to promote moral discipline and physical training, in order to prepare them to fulfill their duties towards the economy and the defense of the Nation (BRASIL, 1937, p. 13).

Following in the footsteps of the Magna Carta, the 1947 Constitution of the State of Minas Gerais also provided for the mobilization of body practices at school. Its article 131 prayed that:

Art. 131. The State shall stimulate and supervise the practice of physical education and sports throughout its territory.

Single paragraph. Gymnastics exercises are compulsory in all public or private schools (MINAS GERAIS, 1947, p. 22).

The school was a privileged place for the dissemination of the body practices of children and youth, and Physical Education increasingly occupied a consolidated place in the curriculum of schools in the country. In 1949, the Physical Education teacher of the João Alcântara School Group, when summarizing her activities for the monthly bulletin, declared “discipline is provoked through religion, taught to students, making them docile and obedient. I have not encountered any disciplinary difficulties” (GRUPO ESCOLAR JOÃO ALCÂNTARA, 1949, p. 34). The teacher completes the record and finalizes, “the students concentrated and attentive, executed well the gymnastics exercises and learned the rules of some sports. Every time the Group appeared in public in demonstrations and competitions, it always got the most heated acclaims” (ibid., p. 34).

The School and the State sought to ensure responsibility in forming the bodies and strengthen their action on physical fitness. During the entire school career, children and youth went through an educational process guided by hygiene, discipline and body docilization. As Lenharo (1986, p. 77) postulates, “the body becomes a producer of morality, because it produces the moral standards desired by the state. Moreover, at the same time that the body is a producer of a morality, it also becomes a transmitter of it”.

In this same line of reasoning, Horta (1994, p. 66) states that Physical Education would provide “students with the harmonious development of body and spirit, thus contributing to the formation of the man of action, physically and morally healthy, joyful and resolute, aware of his value and his responsibilities”. This relationship was not made by chance at that time, since Physical Education linked to the sanitary principles of the nineteenth century acquired at the beginning of the twentieth century, hygienic contours and began to be treated by public authorities and educators as an agent of public sanitation, in the search for a society free of infectious diseases and addictions that deteriorated the health, character and morale of man (CORRÊA, 2008).

In this way, the morally and physically disciplined individual would be prepared for the government’s wishes. The perspective was that of a healthy, robust and resistant body, however, it is noted that expectations exceeded the physical plane, reaching an obedient body to the Homeland.

Starting with the body, Lenharo (1986) states that the state has traced a physical identity, a uniformity for the Brazilian, giving meaning and form to the population through moral education, but also through physical education. All this would guarantee the desired unity and, at the same time, ensure the future of the national and race.

About this supposed race, it is important to say that the years 1930-1940 were characterized, in much of Europe, by the discussion of eugenics and the constitution of a pure and strong race that embodied the imaginary of an ideal nation. This search for national identity, personified by political and social elites, through the construction of a symbolic race, was also present in Brazil during the Estado Novo regime. The text contained in the minutes of the 1942 Physical Education Conferences is illustrative:

The new physical education should form a typical man, who has the following characteristics: slimmer than full, graceful of flexible muscles, light-eyed, agile, healthy skin, agile, awake, upright, docile, enthusiastic, cheerful, virile, imaginative, master of himself, sincere, honest, pure of acts and thoughts, endowed with a sense of honor and justice, sharing in the fellowship of his fellow men, and carrying the love of Providence and men in his heart (XAVIER, 1999, p. 35).

Besides being white and beautiful, the economic and political elites affirmed that man needed to be strong to support the rhythm of daily work, virile to generate more eugenicized Brazilians and docile to collaborate with state interventions (of reference, without resistance). The improvement of the supposed race, however, implied not only biological issues, but mainly moral issues, such as good customs and good habits, including sexual ones.

As Oliveira points out (2008), in 1939 was founded the first onfootball team in the city of Porteirinha, the Porteirinha Futebol Clube. The newspaper Gazeta do Norte printed an invitation to the population of the entire region to join the new association:

The man of today must face life differently. He needs to have other resources, it is indispensable to prepare him not only intellectually and morally, but physically. It is urgent to strengthen man, to improve his physical condition, to ensure his organic balance, to endow him with special conditions, and finally to make him strong in three aspects: physical, moral and intellectual.

Therefore, the guidelines of the Club tend to stimulate the youth in the practice of sports, seek to propagate the moral and social purposes of physical activities and raise public attention to this aspect of the educational problem, supporting the program of government, to improve and enhance our race. Therefore, O glorious youth, direct your attention to these guidelines, seek to cooperate with this association for the aggrandizement of yourselves, thus aggrandizing our country (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1943b, p. 4).

We emphasize that the development and discipline of the body had meaning on eugenic and improvement bases of a supposed Brazilian race. See that the newspaper presents the guidelines of the team, postulated in the ideal of the new Brazilian. The Porteirinha Futebol Clube had as objectives to strengthen the man, to improve the physical, to make him strong and to assure the organic balance. By participating in the club, the subject cooperated with his physical and moral health, but also with the association and the country.

In the eyes of the population, the founding of a football club would mark the beginning of the spread of this practice in Porteirinha. Initially restricted to members of the city’s elite, football, volleyball (see Figure1) and other sports were received with excitement. Oliveira tells how they were inserted in the city:

In 1940, the city started to have a sand box for high jumps; and also a basketball court [...]. Volleyball was practiced daily, always with good assistance, in the schoolyard. The practitioners of this sport, at that time were: José Gomes de Oliveira, Antonio Nunes da Silva, Olegário Bonfim and his brother José Bonfim, Anfrísio Coelho and his brother Antímio Coelho, Alcebino Santos (Major) and Waldeck Cardoso (OLIVEIRA, 2008, p. 90, emphasis added).

In addition to being the place where the children’s bodies were formed, the school also served the local youth. With the purpose of “propagating the moral and social ends of physical activities”, the members of the elite, duly uniformed, gathered at school for the practice of sports. At the time, sport could contribute to the important task of curbing addictions and loitering, improving morale and proper behavior.

Source: CIDADE MINEIRA. Porteirinha. Photo Gallery, 2016. 1 photo. Available at: http://www.cidademineira.com.br/galeria_fotos.php. Access on: 10 Apr. 2016.

Figure 1 Porteirinha/MG Men’s Volleyball Team

To the female public, the Gazeta do Norte, in 1943, reported on the value of body practices as well as the advantages of eugenicist politics:

Female physical education is the first chapter of all physical regeneration. In the reconstruction that Brazil is going through, in the desire to lead and prepare a healthy and optimistic youth, female gymnastics imposes itself as a powerful adjunct to eugenics. It aims first and foremost at health. And health is what is most precious for the mortal being, and for the woman it is a necessity. Women’s physical education aims at obtaining organic vigor, increasing their resistance, putting them in better conditions to fight effectively against diseases. It aims at dexterity, acquiring muscular and nervous habits adaptable to the practical life, and finally, as a crowning of the previous qualities, appears the quality that is the apanagio of the woman: the beauty (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1943a, p. 5).

Behind this discourse where health and beauty were indispensable to women, there was a subtle social control over the improvement of the racial qualities of future generations. According to Soares (1994), at the time maternity was based on principles of hygiene and eugenics. Hygienists preached the “pedagogy of good hygiene”, while eugenicists preached about good procreation, studying the influence of genetic inheritance on the physical and mental qualities of individuals.

The powerful nationalist spirit of the time corroborated with the thought that a woman should generate strong children who could collaborate with the future of the nation. Thus, eugenicists, together with hygienists, recommended that women should also be healthy in order to be able to generate their offspring of equal standing. This speech can be found in another issue of the Gazeta do Norte:

In all times the problem of human regeneration has never been more of a concern to governments than it is now. Eugenicists have been unceasingly concerned to ensure a promising future for future generations. And to make them composed of peace and labor - there is only the resource of the practices dictated by EUGENICS, the only ones that effectively influence the links in the chain of life represented by the cells of immortality of the species.

It is up to women to conserve the species in the investigation of the race; it is their health and vigor that depend on the strong, splendid, victorious generations, who will always conduct with brilliance the luminous beam of a vigorous heredity through the generations to come. The woman needs to be healthy, beautiful and strong and only a rational physical education methodical and scientific, she will find the infallible and necessary means to obtain these superior qualities. The woman of today needs, therefore, to practice physical exercises to conserve her youth, her beauty, the flexibility of the joints, the balance of the forms, the freshness of the skin, the stiffness of the muscles, the vigor of the organs and the capacity of resistance. He needs to escape from a sedentary life and look for the sports squares, the stadiums, an outdoor life in joyful and healthy competitions. It is a duty to himself and to Patria (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1944, p. 6).

The print makes a link between the female image and obedience to some rules for the care of maternal health. It also represents a delicate and maternal woman, who should take care of her health so that she can fulfill her purpose: to generate, raise children and contribute to the formation of strong and healthy men for the “aggrandizement of the race and the Homeland”. Female Physical Education would be the indispensable instrument for this purpose.

Besides the need to strengthen her body, the woman needed to possess a character of virtue, defined by the appreciation of qualities such as generosity, kindness, decency and self-denial (GOELLNER, 2003). Because of this, the care for health was essential, because she was seen as necessary for a woman to be beautiful and be prepared, in all ways, to bear a child.

For the thinking of the time, eugenics was necessary so that ideals could be described from the progressive improvement of the species, promotion of a good generation, healthy and/or healthy procreation, and physical, intellectual, and moral improvement of the individual. For this, all people would be responsible for such an undertaking. The following newspaper cut out this call to society for the formation of a good generation:

Mothers of families, collaborate with these guidelines by sending your sons and daughters in search of the key to happiness in order to adjust to the magnificent closure of harmonies. Try to instill in your children the daily habits of physical education so that it accompanies them through life outside with the enexhaustible source of invaluable physical and moral predicates and reproduce themselves for generations to come, as a powerful collaboration of strength of the race and aggrandizement of our Brazil. The strong mothers are the ones who make the people strong (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1944, p. 6).

Lenharo (1986, p. 79) gives the name to this movement of corporativization, which “obstinately pursues not only the configuration of a unique physical type for the Brazilian, but also aims at the definition of a single racial profile, to the point of establishing a simple relationship between race and constituted Nation”. The importance of the body’s treatment was crucial and the projection of a physical and balanced part with the spiritual dimensioned a balanced social whole, in which tensions and conflicts were left out of place by the singular nature of its constitution.

The formation of a strong and prosperous race and the moral and intellectual formation of Brazilian youth were closely linked to the “regeneration of the race”. Physical exercises were used as a powerful instrument for the “medicalization of Society” (SOARES, 1944, p. 81). It was important to implement hygiene as an educational strategy. Physical education “would provide energy and vigour to children and young people, bringing them closer to nature through direct experience, which would lead them to new sensibility, aesthetics, to what was morally correct” (OLIVEIRA; BELTRAN, 2013, p. 29).

In this sense, in white uniform and long skirts, some women from Porteirinha often gathered for the practice of volleyball, as shown below:

Source: OLIVEIRA, Palmyra Santos. Porteirinha: memória histórica e genealogia. Belo Horizonte: O Lutador, 2008, p. 91.

Figure 2 Porteirinha/MG Women’s Volleyball Team

The memorialist Palmyra Santos Oliveira tells who were the participants of the sports team:

The female team included Dame Marocas Fonseca (wife of Mayor Doc. Altivo), Hilda Martins Gomes (Dida), Raquel and her sister Belica Lacerda, Rita and her sister Marluce Gomes, Nadir Brito, Dame Rola (wife of Mr. José Clemente, City Hall inspector), Licinha and her sister Izene Coelho, Suzete Rosa de Brito, Geralda Nunes de Brito (Picucha), Bebete Cardoso, Jandira Machado, Lindalva Antunes da Silva, Bichim e Branca de Jovêncio, Dedésia Angélica Teixeira, Palmyra Santos Oliveira etc. (OLIVEIRA, 2008, p. 90, our griffon vines).

As specified by the author, the players were socially recognized women and the names in prominence are the teachers of the João Alcântara School Group. In the photograph, the expression of body rectitude tells us a lot about the moral standard. Beauty, maternity, femininity and health were desired both by the media that disclosed them and by the population itself, which in its social imaginary identified in women a means for the modernization of the country. Characteristics such as beauty, health, perseverance, dedication, youth, prudence and disposition should be transformed into virtues conquered in front of women’s participation in society, including in the places where body practices and sports activities were carried out (GOELLNER, 2003).

In general, the belief of intellectuals and politicians that the construction of a prosperous nation and state depended largely on the triad of “intellectual, moral and physical education” of the subjects was strengthened. The State’s action on the physical formation of Porteirinha’s youth can be seen in Law n. 27 of February 25, 1949:

The people of Porteirinha by their legaes representatives, decreed and I, on their behalf, sanction the following law:

Article 1º - The executive power is authorized to donate to the local Sport Association the amount of CR$150.00 (one hundred and fivey cruises) per month, whose purpose will be the physical development of local youth.

Article 2º - The opening of a special credit in the amount of CR$1650,00 is authorized to occur to the expenses referred to in Article 1º (PORTEIRINHA, 1949, p. 381).

For the formation of the children in the mould of that triad, the Porteirinha Scout Group was founded in 1942. According to Horta (1994, p. 199), “the aim of Scouting was to educate the young people in the life of the group, in spirit and discipline, opposing the aspiration of independence and inculcating in them moral and Catholic principles”. The purpose of this movement in Porteirinha was to enhance the physical, intellectual, social, affective and spiritual qualities of children and youth and to train responsible and useful men. The group carried out activities that had as their pillars civism, understood as “patriotic consciousness”, moral education as “spiritual elevation of personality” and Physical Education (PORTEIRINHA, 1942, p. 268).

By Decree Law n. 37 of November 8, 1942, the group began to receive an annual subsidy of 1,000 cruises from the municipal government. In a speech during the foundation of the Scout Group, the mayor of Porteirinha, Altivo de Assis Fonseca, said:

It is essential at this time to offer the children and young people of our glorious Brazil a safe, fruitful and precise orientation. This orientation is the creator of a superior spiritual mentality, praised in the grandiose ideal of the mystical conception of Patria. The Scouts Group came to the city to expand the sublimated tasks of the school, and to form disciplined and healthy citizens based on the highest standards and moral values for the growth of our country (FONSECA, 1942, p. 1).

National education had as its objective the formation of the complete man, useful to social life, by the preparation and improvement of his moral and intellectual faculties and physical activities, this being the primary task of the family and public powers. The transmission of knowledge was to be his immediate task. It was also part of the general principles to define what should be understood by “Brazilian spirit”, that is, the orientation based on the Christian and historical traditions of the Homeland, as shown in the previous excerpt (SCHWARTZMAN; BOMENY; COSTA, 2000). Thus, an individual who achieved a superior physical and psychic quality could not shy away from fulfilling another role within society that did not aim at another eminently necessary purpose: that of well serving Brazil.

According to Azzi (2011, p. 105), “body training was considered a fundamental aspect to facilitate people’s entry into urban society. The posture was a constitutive element of the educational process”. This aspect was strengthened with the Physical Education classes and with the participation of students in civic parades. This time, the patriotic demonstrations were a powerful instrument used to show the local population the importance of education, capable of leading hundreds of children and young people to the streets, in full order and discipline.

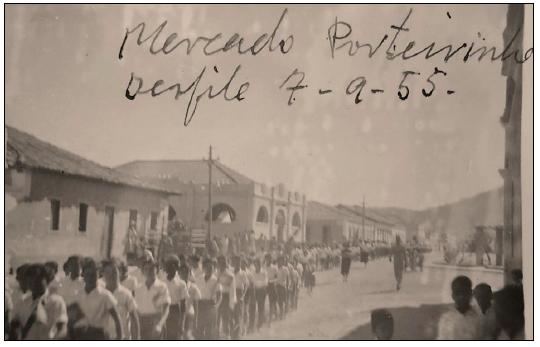

In 1955, priest Julião Arroyo Gallo5 vicar of the city of Porteirinha, photographed the civic parade of September 7 that had the usual participation of the students of the João Alcântara School Group.

Source: GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de fotografias. Desfile 7 de setembro de 1955. 1 fotografia, Porteirinha/MG, setembro de 1955.

Figure 3 Parade of September 7, 1955 in Porteirinha/MG

In these parades, the body should be kept upright, with the shoulders pulled back and the chest enfunado forward. All the movements were to be executed immediately, as soon as the orders of command were received. The body was trained for immediate obedience. The pupils were educated to pay homage to the national symbols as well as to the constituted authorities. Through rigid body movements, pupils learned to express their decision and serve their country, submitting themselves to the higher authorities, who were responsible for deciding upon the directions to be taken in conducting the country (AZZI, 2011).

To produce strong bodies, docile and capable of meeting the demands of the country was the desire of the Brazilians responsible for making the educational system and public institutions work. Thinking about the body of children and youth, inside and outside the school, leaders conducted campaigns with the intention of transforming the reality of these bodies that, in the near future, would take the place of representatives of the Homeland (PYKOSZ; OLIVEIRA, 2009).

Another event held in the city of Porteirinha in August 1944, which took place through the Symbolic Fire Race of the Homeland, the Mayor Altivo de Assis Fonseca set up a prestigious commission to welcome the embassy and promote the organization of civic solemnities for August 12 of that year. The commission was composed of teachers from the School Group, public servants and businessmen (PORTEIRINHA/MG, 1944, p. 196).

According to Rolim and Mazo (2009), the Symbolic Fire Race began in 1938 and emerged as a tradition rooted in the Estado Novo regime. The Race began with a torchlighting ceremony, followed by the passage of the torch to the athletes through a relay through the cities, until the arrival at the pyrelighting ceremony in Porto Alegre, during Homeland Week.

The Race was part of the process of building a Brazilian national identity proposed by the Estado Novo regime. This tradition reinforced the bonds of solidarity between members of society sharing myths and common memories seeking to build a representation of cohesion or national unity in people’s imaginary. This representation took place mainly through the format of touring Brazilian cities (ROLIM; MAZO, 2009).

In 1944, the passage of Symbolic Fire Race in Porteirinha moved the João Alcântara School Group and local sports associations. The sports clubs should demonstrate their patriotic feeling, engage in the activities of reception of the embassy and promote sporting events aimed at the “union of races and brazilians” (GALLO, 1944, n/p).

With the help of the School Group teachers, priest Julião was responsible for planning and organizing the patriotic celebrations, the reception of authorities and athletes, and the festive celebrations, which included the sports competitions. During the official reception of the embassy in the city, priest Julião gave the following speech:

On behalf of the town, I have the great honor and undisguised satisfaction to present to you our best wishes. [...] The population of this mining unit in formation, a piece of the hinterland of Minas Gerais, prides itself on its honorable passage. First, I would like to register that sport is an effective antidote against softness and life in comfort, it awakens a sense of order and educates to examination and self-control, to contempt for danger without boastfulness or faintheartedness. Thus, it goes beyond physical robustness to lead to strength and moral greatness. The practice of sports is the provider of social coexistence, an instrument for improving health and strengthening the collective will, representative components of good christian conduct. [...] Finally, sport forms the new man, loaded with civism, morality and patriotism. Sport forms the disciplined, hardworking and educated man for the New Brazil (GALLO, 1944, n/p, emphasis added).

In his speech, the parish priest sought to highlight the governmental intentions of the political project of the time by citing the cultural identity being constructed from a man postulated by civism, morality and patriotism. However, he made an interpretation of sport through the Catholic gaze when he affirmed that the experience of sport is a provider of good Christian conduct. In the next section, we will see how bodily practices have been incorporated into the doctrine of Catholicism.

The body that energises the soul and strengthens the faith: sport and the Catholic Church

Don’t you know that in the stadium all athletes run, but only one wins the prize? So run, to get the prize. The athletes abstain from everything; they, to win a perishable crown; and we, to win an imperishable crown. As for me, I too run, but not as one who goes aimlessly. I practice boxing, but not as one who fights the air (BÍBLIA SAGRADA, 1Cor. 9, 24-27, 1990, p. 1399).

In the excerpt, the apostle Saint Paul, in the book of Corinthians of the Holy Bible (1990), speaks of sport and the care of the body. Through the metaphor of sporting competition, he highlights the value of life, comparing it to a race towards a goal that is not only earthly but transcendent and divine. Thus the apostle invites Christians to become athletes of God, faithful and fearless preachers of the Gospel. For Saint Paul, the practice of sports can also lead man to God. Remember the apostle:

Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, who was given to you by God, and who does not belong to you? For you have been redeemed at a high price! Therefore glorify God in your body (BÍBLIA SAGRADA, 1 Cor. 6:19-20, 1990, p. 1399).

According to Werle and Metzler (2010), for Christian culture, the physical is a representation of the soul and of the levels of closeness to the transcendent, the first step to begin the process of formation of the person and, in this case, of the future educator. The model of Christian education, normatized by the Catholic Church, has adopted the practice of sports as a mediator of the principles of faith characterized by social coexistence, care and discipline of the body to achieve spirituality.

Thus, the religious institution was interested in participating directly in the performance, discipline and shaping of bodies. For her, sport was an instrument capable of adding spiritual values. It was a cultural practice capable of spiritualizing the physical, motor and biological dimension of man. Finally, for the Church, sport helped man to be dignified and elevated; it would be an instrument for proclaiming the word of God.

As a pedagogical tool, sport, since the Brazilian colonial and imperial period, was already present by the initiative of the Jesuits and religious of other orders, in their schools. In Montes Claros, the largest city in the north of Minas Gerais, for example, the insertion of sport can be attributed to the action of the Premonstratense order. At the beginning of the 20th century, priest Vincart, one of the first Belgian missionaries to arrive in this city, used soccer as a tool to attract young people and form the population by practicing the sport (SILVA, 2012).

One of the main analyses of the Catholic Church’s bodily practices at the time was expressed by pope Pio XII in 1945. Speaking to the youth of Catholic Action that year, the Pontiff stated that “sport, when well understood, represents the occupation of the whole man, perfecting body and spirit, helping him to reach the end: the service of worship of the Creator” (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1945, p. 3).

Let us look in more detail at the Church’s ideas on the practice of sports, widely reported in local newspapers:

Pope Pio XII says that sport has much value, but instead of being considered as an end, it should be considered as a means to improve man intellectually, morally and physically. Sport, properly directed, develops character, makes a man brave, a generous loser and a gracious winner. It refines the senses, gives intellectual penetration and strengthens the will to resist. It is not just a simple physical improvement. [...] In the service of a healthy, robust, ardent life, in the service of a more fruitful activity in the fulfillment of the duties of one’s own state, sport can and must also be in the service of God. To this end he inclines the spirits to direct the physical forces and moral virtues which he develops; but while the pagan submits to the severe sporting regime in order to obtain only a perishable crown, the Christian submits to it for a higher scope, for an immortal prize (GAZETA DO NORTE, 1945, p. 4).

For Pio XII, sport was a mediating component of evangelization fully integrated with Catholic doctrine. His words are close to the concept of physical education that associates sport to health, but especially to good behavior. Health integrates the physical and spiritual components, while good behavior is specified in the ideal of Christianity. The body should not be divinized, but improved, because, according to the religious view, what differentiates man from the rest of the animals was not the physical strength, but the intellectual and spiritual question. Then, as St. Augustine affirms, the work of the body should be done to improve intellectual performance and, at the same time, to help in the spiritual sense, since the Church sees in the body a simulacrum of the spirit6 (AGOSTINHO, 2000).

For the Pontiff, the Church is interested in forms of body education, such as sport, which has an important educational function:

Modern sport, conscientiously exercised, strengthens the body, makes it healthy, strong and full of life to carry out this educational function; sport subjects the body to a rigorous and at times harsh discipline that dominates it and truly retains it in servitude: training for fatigue, resistance to pain, habits of continence and severe temperance, all indispensable conditions for those who want to achieve victory. Thus he goes beyond physical robustness to lead to strength and moral greatness (PIO XII, 1953, p. 4).

The Catholic tradition has associated educational formation with faith, understanding man in the physical and psychic aspects, guided by the spiritual aspect. For the Church, the physical dimension was centered on the corporal experience and represented the first stage of the person, believing that the transcendent meaning of life reflected in the way the body was treated and valued. The moral dimension, associated with the process of communication, had a greater scope than the physical, because at this level is the process of participation, integration and consciousness. The spiritual dimension, while the fundamental one, included the search for meaning in life, religious experience and dialogue with God (WERLE; METZLER, 2010).

The newspaper A Verdade brought the concept of “physical, intellectual and moral education”, and the appreciation of the latter:

Indeed, man’s physical and intellectual development is an immense good, but that is not enough - moral life is indispensable to him. It demands the formation of the will, of conscience and of the heart; it encloses the customs, that is to say, the habits, the uses and all the conduct of man. [...] But this moral education must be religious - for there is no true morality without religion! (A VERDADE, 1907, p. 3).

This same line of thought is supported by Pio XII, in 1952, when he speaks to Physical Education teachers in Rome:

When the religious and moral content of sport is carefully respected, it must enter into the life of man as an element of balance, harmony and perfection, and as an effective aid in the fulfilment of other duties. Therefore base your joy on the correct practice of gymnastics and sport. Bring to the midst of the people their beneficial current so that physical and psychic health may prosper more and more, and bodies may be strengthened in the service of the spirit; above all, do not forget, in the midst of the hectic and intoxicating gymnastic-sport activity, that which in life is worth more than all the rest: the soul, the conscience, and, at the supreme apex, God (PIO XII, 1953, pp. 13-14).

For the pope, “sport and gymnastics should not command and dominate, but serve and help. It is their function, and there they find their justification” (PIO XII, 1953, p. 8). To conclude the analysis, he concludes: “Do you want to act righteously in gymnastics and sport? Observe the commandments of God!” (ibid, p. 14).

In Porteirinha, during the opening of the Intermunicipal Sports Championship in November 1941, involving this city and that of Grão Mogol, priest Julião told the athletes and the community:

Using the sport, today an important step was taken that aims to bring together all the citizens of Porteirinha and Grão Mogol here present. We want the spirit of loyalty, enthusiasm, cordiality and fraternity to make this event transcend the sporting competition and become an extra step in building strong, upright and civic men. The “Porteirinha Sport Club” takes a proficient step in the development of physical culture in this place; but not only that, this action provides the pleasant construction of bonds of camaraderie and union. We know that the sport is of great necessity, and it enters today in almost all the programs of education. The sport develops the muscles, activates the circulation, improves the traits, modifies the gestures, punishes the habits and deprives the vice, interweaves and unites friendly hearts and forms the character! (GALLO, 1942, n/p).

Still in his speech, the priest made explicit the Catholic conception of sport:

On sport, dear athletes, good religion says: “first of all, render to God the honor that is due to Him, and above all, sanctify the day of the Lord”. In this way, the practice of sport does not exempt anyone from religious duties and from participating in Mass. Do not forget also that the Creator wants harmony and affection within the family. Remember, therefore, fidelity to family obligations which must be preferred to the supposed demands of sport and of sports associations (GALLO, 1942, n/p).

The Tridentine look at sports and gymnastics arrived in Porteirinha by priest Julião, and it seems that body practice has integrated into the culture of faith. In the João Alcântara School Group, body experiences, such as initiation to sports, games and dances, were fundamental contents. The body practices were present in several school times and spaces: the sport initiation was present in Football; dances were rehearsed for the presentations in the auditoriums; the games were held during the excursions; and in order to brighten up the patriotic celebrations in the city, the Physical Education teacher trained exercises and gymnastic numbers to be shown in the public presentations (GRUPO ESCOLAR JOÃO ALCÂNTARA, 1946).

These actions were in accordance with official legislation. The Organic Law of Primary Education, Decree Law n. 8.529, of January 2, 1946, ensured that the purpose of this level of education was “to provide the cultural initiation that leads to the knowledge of national life, and the exercise of the moral and civic virtues that maintain it and enhance it (BRASIL, 1946, p. 1). Physical Education, as an obligatory curricular component, had much to offer to this model of civic and moral formation of children and youth.

In this way, if the political component dictated the paths of education, the religious traced the way forward. The Physical Education teacher of the School Group wrote about a sports day of the Children’s Week programme, in 1952:

In the morning, before we left for the Church, I taught the students lessons on how to do well in the street and the obedience they should have to my orders by training them morally. At headquarters, everyone behaved and remembered the good manners and the rules of respect and education. In the afternoon, there was an enthusiastic and festive football match between the classes of the Group. Before the matches, the National Anthem was sung, and at the beginning of each game, the students prayed for health and victory. I noticed that the boys put into practice the spirit of cordiality, good will, energy and the joy of living. At the end, after being served a hearty snack, I read the message: “seek to work and win medals, but above all, seek the main trophy of life: God” (GRUPO ESCOLAR JOÃO ALCÂNTARA, 1952, p. 15).

According to Souza (2008), this period required a policy of engagement between the state, which needed the legitimation of the Catholic hierarchy to enforce its proposals, and a Church, which channelled its efforts to obtain favors from the new authoritarian regime. “This alliance of friendly outlines would represent the conviction that only united in the same purpose and distinct in its organization and competence would Church and State be able to create and sacralize a new harmonious social order” (SOUZA, 2008, p. 172).

The body practices have been covered with religious elements. The teacher taught the ways of behavior, the moral precepts in force and a rationalization of the body for the faith that involved postures, gestures and behaviors. See that part of the school time and activities of Children’s Week was dedicated to thanking God. The students, in turn, understood this message and put into practice Christian manifestations, such as prayers before the game and the consecration to Christ for the victory achieved.

This speech, no doubt, reminds us of the dialogue between Teacher Olívia and her students, described at the beginning of the section. The various body manifestations present in Porteirinha allowed us to think about the construction of bodies in the perspective of making them grow, develop and reproduce, as the student Maria thinks. Men and women seeking to make their bodies cleaner, more productive, morally effective, a body thought of as a machine that produces, as Mário justifies. It also made us imagine the body as a house that needed to be built, as the student Jaime points out. In this aspect, the body, submitted to the modelling action of the original powers of the family, the State and Catholicism, took contours and paths that led it and built it under the ground of morality.

Finally, school, in a special way, “would provoke in the children a change of sensibility, language, behaviour and even personal perspectives. This is a new representation that is being consolidated around the place of school in social practices”, as Vago writes (1999, p. 31). In this way, the formation of intelligent, strong, civic, disciplined and docile men, from education and physical education, was sought and pedagogical discourses revealed traces and allowed us to decipher daily experiences, the network of sociability and postures of children, young people, teachers and leaders. It produced bodies that speak, that energize the soul and strengthen the faith.

Final considerations

The Physical Education in the João Alcântara School Group sought to ensure responsibility in forming the bodies and strengthen action on physical preparation. Children and youth were educated, sanitized and shaped by the institution. The discipline sought to docile the bodies to be better used by the Brazilian government project, which sought to form a new Brazilian. This process also embraced women, as it included the representation of a delicate and maternal woman who should take care of her health so that she could fulfill her purpose: to generate, raise their children and contribute to the formation of strong and healthy men for the advancement of the race and the Homeland.

The Catholic Church has also made an interpretation of the sport and has proposed to participate directly in the performance, discipline and shaping of the bodies. According to the Church, the experience of sports was a proportion of good Christian conduct. Sport and Physical Education were instruments of spiritual values, that is, they formed a cultural practice capable of spiritualizing the physical dimension of children and young people.

The School Group valued and idealized the moralistic dimension in education. The government, in turn, expected the support of all moral forces. Together with the Catholic Church, the school was one of the means to sanitize the moral environment of Porteirinha. The practices developed within that school space can be understood as producing senses and identities. These senses, in a way, were sedimented by the insertion of Catholicism in the public school.

Finally, in concluding the presentation of the research results, the data reveal traces and allow us to decipher daily experiences, the network of sociability, postures and compact codes. It is thus explained that the theme developed in the work is quite current and perennial. Issues such as Religious Education in public schools, the School without Party project, secularity and the influence of religion in the various spaces arrive to the present day and, with great force, are discussed in the legislative chambers, in the senate and in various places that debate social and educational policies.

REFERENCES

AGOSTINHO, Santo. Confissões. Coleção Os Pensadores. São Paulo: Nova Cultural, 2000. [ Links ]

AZZI, Riolando. A Igreja Católica na Formação da Sociedade Brasileira. 9. ed. Aparecida: Santuário, 2011. [ Links ]

BERCITO, Sonia de Deus Rodrigues; NOVINSKY, Anita. Ser forte para fazer a nação forte: a educação física no Brasil, 1932-1945. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1991. [ Links ]

BÍBLIA SAGRADA - Edição Pastoral. 34. ed. São Paulo: Paulus, 1990. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição (1937). Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, 10 de novembro de 1937. Disponível em <http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/ consti/1930-1939/constituicao-35093-10-novembro-1937-532849-publicacaooriginal-15246-pl.html>. Acesso em: 17 out. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto-lei n. 8.529, de 2 de janeiro de 1946, Lei Orgânica do Ensino Primário. Rio de Janeiro, 2 de janeiro de 1946. Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/ fed/declei/1940-1949/decreto-lei-8529-2-janeiro-1946-458442-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em: 26 ago. 2016. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Carlos Henrique de; CARVALHO, Luciana Beatriz de Oliveira Bar de. História/historiografia da educação e inovação metodológica: fontes e perspectivas. In: COSTA, Célio Juvenal Costa; MELO, Joaquim José Pereira; FABIANO, Luiz Hermenegildo. Fontes e métodos em história da educação. Dourados/MS: UFGD, 2010, p. 79-110. [ Links ]

CORRÊA, Denise Aparecida. A Educação Física Escolar nas Reformas Educacionais do Ensino no governo de Getúlio Vargas. In.: VIII Congresso Nacional de Educação - EDUCERE: Formação de Professores. Curitiba: PUCPR, 2008, p. 222-234. [ Links ]

GOELLNER, Silvana Vilodre. Bela, maternal e feminina: imagens da mulher na Revista Educação Physica. Ijuí/RS: Unijuí, 2003. [ Links ]

HORTA, José Silvério Baia. O hino, o sermão e a ordem do dia: regime autoritário e a educação no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 1994. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA (IBGE). Recenseamento Geral do Brasil de 1º de setembro de 1940. Série Regional - Minas Gerais, Tomo 1. Censo Demográfico, população e habitação. Rio de Janeiro, 1950. [ Links ]

LENHARO, Alcir. Sacralização da Política. 2. ed. São Paulo: Papirus, 1986. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marcos Aurélio Taborda de; BELTRAN, Cláudia Ximena Herrera. Uma educação para a sensibilidade: circulação de novos saberes sobre a educação do corpo no começo do século XX na Ibero-América. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Campinas, v. 13, n. 2 (32), p. 15-44, mai./ago. 2013. https://doi.org/10.4322/rbhe.2013.024 [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Palmyra Santos. Porteirinha: memória histórica e genealogia. Belo Horizonte: O Lutador, 2008. [ Links ]

PYKOSZ, Lausane Corrêa; OLIVEIRA, Marcus Aurélio Taborda de. A higiene como tempo e lugar da educação do corpo: preceitos higiênicos no currículo dos grupos escolares do estado do Paraná. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 9, n. 1, p. 135-158, jan./jun., 2009. [ Links ]

REVISTA VIDA E SAÚDE. Para meninos e meninas. Santo André/SP, v. 3, n. 11, novembro de 1941, p. 16. [ Links ]

ROLIM, Luís Henrique; MAZO, Janice Zarpellon. A Corrida de Revezamento do Fogo Simbólico da Pátria em Porto Alegre (1938-1947): estudo sobre a participação dos clubes esportivos. Movimento. Porto Alegre, v.15, n.4, p.11-33, out./dez., 2009. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.5704 [ Links ]

SCHEIDER, Omar. A Revista Educação Physica (1932-1945): circulação de saberes pedagógicos e a formação do professor de Educação Física. In.: Congresso Brasileiros de História da Educação (SBHE). Natal, 2002. [ Links ]

SCHWARTZMAN, Simon; BOMENY, Helena Maria Bousquet; COSTA, Vanda Maria Ribeiro. Tempos de Capanema. 2. ed. São Paulo: Fundação Getúlio Vargas; Paz e Terra, 2000. [ Links ]

SILVA, Luciano Pereira da. Em nome da modernidade: uma educação multifacetada, uma cidade transmutada, um sujeito inventado (Montes Claros, 1889-1926). Tese (Doutorado em Educação), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2012. [ Links ]

SOARES, Carmen Lúcia. Educação Física: Raízes Européias e Brasil. 2. ed. Campinas: Autores Associados, 1994. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rogério Luiz de. A Igreja Católica no processo de Nacionalização. In.: SOUZA, Rogério Luiz de; OTTO, Clarícia (Orgs.). Faces do Catolicismo. Florianópolis: Insular, 2008. [ Links ]

SUCHODOLSKI, Bogdan. A Pedagogia e as Grandes Correntes Filosóficas: a Pedagogia da Essência e a Pedagogia da Existência. São Paulo: Centauro, 2002. [ Links ]

VAGO, Tarcísio Mauro. Início e fim do século XX: Maneiras de fazer educação física na escola. Cadernos CEDES, ano XIX, n. 48, ago./1999, p. 30-51. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32621999000100003 [ Links ]

WERLE, Flávia Obino Corrêa; METZLER, Ana Maria Carvalho. Missão evangelizadora: mediações da prática esportiva. Revista História da Educação, v.14, n.32, set./dez., 2010, p.199-219. [ Links ]

XAVIER, Libânia Nacif. O Brasil como laboratório: educação e ciências sociais no projeto do Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Educacionais. Bragança Paulista: EDUSF, 1999. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

3º Livro de atas do Centro do Apostolado da Oração do Sagrado Coração de Jesus da Paróquia de Porteirinha. Porteirinha/MG, 7 de abril de 1957 a 30 de abril de 1967. [ Links ]

A VERDADE. A Educação Moral (Papel do Pae de Familia). Anno I. N. 25. Montes Claros/MG, 2 de dezembro de 1907, p. 2-4. [ Links ]

CIDADE MINEIRA. Porteirinha. Galeria de fotos, 2016. 1 fotografia. Disponível em: http://www.cidademineira.com.br/galeria_fotos.php. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2016. [ Links ]

ESCOLA MISTA DO DISTRICTO DE PORTEIRINHA. Livro de acta de exames e termo de promoções da escola mista do distrito de Porteirinha. Grão Mogol/MG, 1929. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Altivo de Assis. [Convite]. Porteirinha/MG, 1942. Grupo de escoteiros na cidade. [ Links ]

GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de fotografias. Desfile 7 de setembro de 1955. 1 fotografia, Porteirinha/MG, setembro de 1955. [ Links ]

GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de recortes de jornais. Esportes em Porteirinha. Porteirinha/MG, 17 de dezembro de 1942. [ Links ]

GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de recortes de jornais. Porteirinha/MG, 23 mai. 1947b. Ao Pôvo da Paroquia de Porteirinha - Campanha pró-Matriz Paroquial. [ Links ]

GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de recortes de jornais. O Brasil Novo. Porteirinha/MG, 10 de setembro de 1944c. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. Educação Fisica Feminina. Montes Claros/MG, 20 de fevereiro de 1943a, p. 5. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. O futebol. Montes Claros/MG, 21 de setembro de 1943b, p. 4. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. A importância da Educação Fisica para a mulher. Montes Claros/MG, 7 de dezembro de 1944, p. 4. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. O esporte é um meio de aperfeiçoar o homem. Coluna Vida Católica. N. 1618. Montes Claros/MG, 30 de agosto de 1945, p. 3. [ Links ]

GRUPO ESCOLAR JOÃO ALCÂNTARA. Boletins Mensais dos registros escolares do Grupo Escolar João Alcântara. Porteirinha/MG, 1944 a 1955. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. Livro de atas das reuniões das professoras do Grupo Escolar João Alcântara. Porteirinha/MG, 1956. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. Livro de atas de exames, termos de promoções, de instalação da escola desta cidade e dos termos de visitas dos srs. Assistentes Técnicos. Porteirinha/MG, 1946. [ Links ]

GAZETA DO NORTE. Livro de atas de exames, termos de promoções, de instalação da escola desta cidade e dos termos de visitas dos srs. Assistentes Técnicos. Porteirinha/MG, 01/02/1946 a 16/07/1954. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Decreto n. 885, 30 de junho de 1937. Cria um grupo escolar no distrito de Porteirinha, municipio de Grão Mogol. Diário Oficial de Minas Gerais, Poder Executivo, Belo Horizonte, 30 jun. 1937, p. 217. [ Links ]

PIO XII, Papa. Sobre o Desporte e a Educação Física. (Documentos Pontifícios). Petrópolis, São Paulo: Vozes, 1953. [ Links ]

PORTEIRINHA/MG. Decreto-Lei n. 2, de 16 de fevereiro de 1939. Baixa o Código de Posturas do Município. Livro n. 1 de Leis e Decretos da Prefeitura Municipal de Porteirinha, 2 de janeiro de 1939a, p. 13. [ Links ]

PORTEIRINHA/MG. Decreto-Lei n. 37, de 8 de novembro de 1942. Dispõe sobre concessão de subvenções, contribuições e auxílios. Livro n. 1 de Leis e Decretos da Prefeitura Municipal de Porteirinha, 2 de janeiro de 1939b, p. 189. [ Links ]

PORTEIRINHA/MG. Prefeitura Municipal. Comissão de recepção da Embaixada do “Fogo Simbolico”, ano de 1944. In: GALLO, Julião Arroyo. Álbum de recortes de jornais. Porteirinha/MG, 1944, p. 196. [ Links ]

PORTEIRINHA/MG. Lei n. 27, de 25 de fevereiro de 1949. Dispõe de doação financeira à Associação Esportiva local. Livro n. 1 de Leis e Decretos da Prefeitura Municipal de Porteirinha, 25 de fevereiro de 1949, p. 381. [ Links ]

1This work was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) - CAPES and supported by the Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Norte de Minas Gerais (Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Northern Minas Gerais) - IFNMG.English version by Josué de Andrade Calixto. E-mail: josue339@icloud.com.

2According to the 1940 General Census of Brazil, 72% of people in Porteirinha could not read or write (IBGE, 1950, p. 430).

3In order to maintain the originality of the documents, we chose to keep the original spelling of texts and documents and quote them literally.

4The term body practice, used here, encompasses cultural manifestations that focus on the human body dimension, such as: sport, gymnastics, dance and games. We also understand that body practice can be experienced in the school space (in a synthesized way) and outside it (individually or collectively, informally or in sports associations or clubs).

5Julião Arroyo Gallo was born on July 6, 1904 in Burgos, Spain. Extremely doctrinaire, he arrived in porteirinha in 1941 and articulated with the political, social and educational powers. He was an intellectual who received a better education than most of the local population and was one of the few people who left written several texts located in newspapers, institutional books of the Church and manuscripts about the social, political, cultural and educational aspects of the region. Gallo was at the head of the Porteirinha parish for almost thirty years.

6The idea of the body as a simulacrum of the spirit comes from Augutinian thought. Saint Augustine learns from the Platonic that a materialistic or corporative explanation of the human being alone does not account for the human experience. “From Platonism, Augustine assimilated the conception that truth, as eternal knowledge, should be sought intellectually in the world of divine ideas”. That is why he defended the path of self-knowledge, the path of interiority, as a legitimate instrument for the search for truth (SUCHODOLSKI, 2002, featured author). In his work Confessions, the bishop of Hippo asks: “if happiness is in god and not in carnal pleasures, would the body be an evil to be avoided?”.

Received: April 24, 2020; Accepted: July 08, 2020

texto en

texto en