Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-102

Dossiê 2 - Museus Pedagógicos: diálogos ibero-americanos

The National Pedagogical Museum and educational renewal in Spain (1882-1941)1

1Universidad de Murcia (España). plmoreno@um.es

The National Pedagogical Museum, founded in 1882 was originally known as the Madrid Museum of Primary Instruction. It was created following a proposal from the Free Institution of Teaching as part of its pedagogical and political project to achieve modernization and social transformation in the country. The initiative sprang from the need to undertake the necessary reforms to improve the conditions of primary education, and took as its reference the international museum experience. The Museum, as conceived by its first director Manuel Bartolomé Cossío (1857-1935), was to be the gateway through which all advances in early education in other countries were introduced into Spain. Its main action lines were aimed at teacher training, renewing school furniture and teaching materials, and at becoming the most important centre for information, study, renewal and pedagogical dissemination in the country.

Keywords: National Pedagogical Museum; Spain; Training; Research; Educational renewal

El Museo Pedagógico Nacional, fundado en 1882 con el nombre, inicialmente, de Museo de Instrucción Primaria de Madrid, fue creado a propuesta de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza como parte de su proyecto pedagógico y político para lograr la modernización y la transformación social del país. La iniciativa se vinculaba a la necesidad de acometer las reformas necesarias para mejorar las condiciones de la primera enseñanza tomando como referencia la experiencia museística internacional. El Museo, tal y como fue concebido por su primer director Manuel Bartolomé Cossío (1857-1935), tenía que ser la puerta por la que se introdujeran en España todos los adelantos que en la primera educación se verificaran en los demás países. Sus principales líneas de actuación irían encaminadas a la formación docente, la reforma del mobiliario escolar y el material de enseñanza, así como convertirse en el centro de información, estudio, renovación y difusión pedagógica más importante del país.

Palabras clave: Museo Pedagógico Nacional; España; Formación; Investigación; Renovación educativa

O Museo Pedagógico Nacional, fundado em 1882 em Madri, inicialmente com o nome de Museo de Instrucción Primaria, foi criado a partir de uma proposta da Institución Libre de Enseñanza como parte do seu projeto pedagógico e político. Visava a modernização e a transformação social do país. A iniciativa estava vinculada à necessidade de fomentar as reformas necessárias para melhorar as condições do ensino primário, tendo como referência a experiência museal internacional. O Museo, tal como foi concebido pelo seu primeiro diretor, Manuel Bartolomé Cossío (1857-1935), deveria ser a porta pela qual seriam introduzidos na Espanha os avanços já verificados em outros países em relação ao ensino primário. As suas principais linhas de atuação estavam direcionadas à formação docente, à reforma do mobiliário escolar e do material para o ensino. Propunha-se, também, converter-se no centro de informação, estudo, renovação e difusão pedagógica mais importante do país naquele período.

Palavras-chave: Museo Pedagógico Nacional; Espanha; Formação; Pesquisa; Renovação educativa

Introduction

Following what is known as the six democratic years (1868-1874), at the beginning of the Restoration in Spain, the liberal Sagasta party came to power in 1881, which enabled certain initiatives aimed at tackling the many problems the Spanish school was experiencing at the time. The first attempts at modernization and Europeanization of Spanish education, by Francisco Giner de los Ríos (1839-1915) and the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE) (Free institute of Education), founded in 1876 inspired by Krausist, reformist and regenerationist ideals to renew education as a pedagogical and political project to achieve social transformation of the country, gave rise to the gradual development of public agencies dependent on the State. The first initiative by the liberal administration, fruit of the Institution's enthusiastic and reforming spirit, was the creation of the Museum of Primary Instruction of Madrid in 1882, eventually known as the National Pedagogical Museum based on the budget law of 1894-95. An organisation which would be followed by other entities relevant to the scientific, pedagogical and cultural renewal and modernization of Spain such as the Junta para Ampliación de Estudios e InvestigacionesCientíficas (Board for Advanced Studies and Scientific Research) 1907, the la Residencia de Estudiantes (Student Residence) 1910, the Residencia de Señoritas (Girls Residence) 1915 or the Instituto-Escuela in 1918 (Molero, 2000; Viñao, 2004: 20-27).

The aim of our study is to make a general approach to the historical knowledge of the National Pedagogical Museum of Spain, in the context of the contemporary international museum movement, its origins, openness and international vocation, configuration and purposes, as well as the main actions carried out to favour the reception and circulation of emerging innovative pedagogical ideas and their projection in the transformation of the Spanish school.

Development of the National Pedagogical Museum

In the same year as the first National Pedagogical Congress in Spain, the first Pedagogical Exhibition was also held (Ferrer, 1882), with the liberal José Luis Albareda Minister of Public Works and the General Director of Public Instruction Juan Facundo Riaño (Giner, 1927), the official creation by Royal Decree of May 6, 1882 Gaceta May 7), of the previously named Museum of Primary Instruction of Madrid.

In its explanatory memorandum the Government justified its creation, in the need for reforms that modern societies demanded to “improve the conditions of primary education”. The authorities cautiously expressed the hope that the Museum would become “a nucleus of illustration” generating “enormous advantages”. The choice of an entity of this nature to respond to the existing challenges demonstrated governmental recognition of the development and trajectory that emerging pedagogical museums had been experiencing in the international arena, from their progressive development from the start of the second half of the XIX century, to their potential to transform reality and shape the future (Lawn, 2009).

Following in the wake of such museums, the rule established that the Museum would contain: models, projects, plans and drawings of Spanish and foreign establishments of primary education, furniture and school supplies, scientific and general teaching material, Froebel gifts -an author, whose pedagogical theories comprised one of the most outstanding signs of ILE identity (Otero, 2012: 442)-, games and a library of primary instruction. Its main rules included publishing catalogues of books and objects acquired, organising conferences, being an optional center, holding exhibitions, and displaying exhibited objects to visitors or testing the reproduction of teaching devices and materials. The Museum of Primary Instruction was constituted as an autonomous body, of a technical nature, directly reporting to the General Directorate of Primary Instruction (Moreno, 2012).

Some months later, the Museum's regulations, by Royal Order of July 8, 1882 (Gaceta August 6), provided the educational administration with the opportunity to continue refining the new body. On the one hand, it allowed it to complete the initial functions assigned to it, which would develop and expand over time and, on the other, to set the duties of its technical staff, initially limited to the figures of director and secretary, as well as regulating access to these positions through civil service exams.

One of the most innovative contributions of regulation was the value attached to material culture, to objects in the Museum, as a means to publicise the state of primary education in Spain and other nations, as well as “advances offered by the progress of pedagogy”. The Museum was assigned an eminently technical role, which transcended the Spanish context, as was attention to the study of pedagogical advances in other nations, serving as a reference for introducing possible future educational innovations into our country.

At the same time, regulation set the powers and functions assigned to both positions and detailed the selection procedure. Due to the essentially pedagogical tasks of its managerial staff, far from being reduced to the condition of mere conservators of objects or performing administrative activities, these should have a technical and optional nature. Appointment would be through civil service examination strengthening both the autonomy and technical and scientific authority of the new body (García, 1985: 59-60).

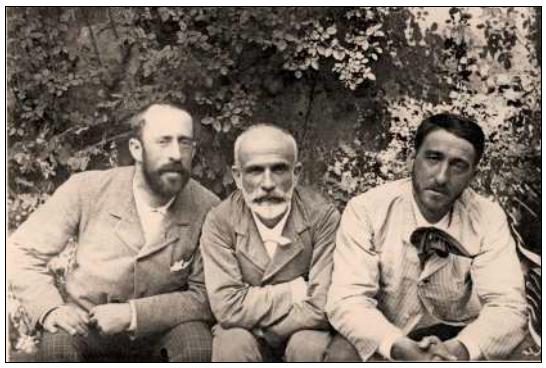

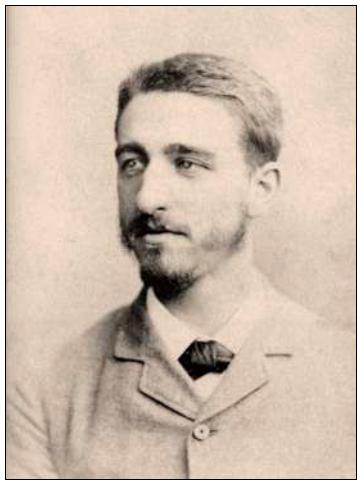

Examinations to fill the positions of director and secretary took place in August 1882, the first for management in late 1883 and the second, for the secretariat, in July 1884. These were temporarily held by Pedro de Alcántara García and Manuel Serrano Marquesi respectively, until inauguration when two important figures linked to the Free Institution of Education who had passed the exam process took over, Manuel Bartolomé Cossío (1857-1935) and Ricardo Rubio Álvarez (1856-1935). Cossío, disciple and follower of Giner de los Ríos, also became director of the Pedagogical Museum, the first professor of pedagogy at a Spanish university in 1904, counselor of public instruction in 1921 and president of the Board of Pedagogical Missions in 1931. Cossio could be considered the most emblematic Spanish pedagogue since the founding of the Institution to the Second Republic, and he was whom Giner trusted to carry out the project.

Vocation of international openness of the Museum and project of Manuel Bartolomé Cossío

As proposed by Marc-Antonie Jullien of Paris, to whom some authors first attributed a pedagogical museum (Pellisson, 1911: 1367), in his work Esquisse d'un ouvrage sur l'éducation idea of instituting comparée et séries de questions sur l' éducation, 1817, to regenerate and improve public education, it was necessary to create, among other initiatives, a “Special Commission on Education, not very numerous and comprising men in charge of collecting (...), the materials of a general work on schools and methods of education and instruction from the different states of Europe” (Jullien, 2017: 9).

The transnational vocation of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE) drove the creation of the Museum and constituted an inherent principle of its project of national modernisation. The relationships maintained by the ILE, and the entities and initiatives that it promoted with the European pedagogical renewal movements were constant (Otero, 2012a; Otero, 2020: 179-181). In the case of the Pedagogical Museum, the purposes attributed to it in the founding legal texts and bases to govern and guide its actions and the characteristics needed by those who chose to manage it, showed that from the beginning the new body had a patent international openness. One test for access to the position of director, for which considerable knowledge of foreign languages was required, consisted of presenting a report containing an idea on the main existing museums, as well as what the director envisioned the Museum to be.

Cossío had a long history of stays in foreign academic institutions and experience in international relations. He had had a scholarship at the Real Colegio Mayor de San Clemente de los Españoles in Bologna, Italy from November 1879 to July 1880, where he made contacts and visited prominent Krausists and educational institutions in Naples, Rome and Venice, as well as other journeys in 1880 to Switzerland, Belgium and France with similar aims. This first tour of Europe allowed him first contact with some pedagogical museums. In Switzerland he visited those in Bern and Zurich, where he met Köller, the director of the city´s museum. In Belgium he attended the inauguration of the Brussels Pedagogical Museum on August 24, 1880, an institution that he highly praised (Otero, 2007: 47-50). Two years later, after having won a position to chair History of Fine Arts at the School of Barcelona, to prepare new appointments to the Museum board, he undertook a new journey for forty days, from August 10, 1882, to personally know, and often revisit some of the main pedagogical museums in Germany, Austria, Belgium, France and Switzerland. On this occasion, Cossío was able to visit the museums of Leipzig created in 1865, Vienna 1872, Zurich 1873, Munich 1875, Berlin 1877, Bern 1878, Paris 1879, Brussels 1880 or Dresden 1881 (Otero, 2012b). A year later, in 1883, prior to the civil service exam for the Museum's board, he made a third trip with Giner de los Ríos to the recently inaugurated Municipal Pedagogical Museum of Lisbon. Adolfo Coelho was the head of this Museum, with whom Cossio shared pedagogical and reformist affinities and would maintain a stable epistolary relationship and exchange of publications over the following years (Mogarro, 2003: 88; Otero, 2004). The impressions made by the pedagogical museums of Europe, in the summer of 1882, were not actually very positive. Cossío would record the following in his personal notes:

Hardly any of the museums I have seen has a well-defined purpose or knows where it is headed and what it should and should not do and how far it can be extended and where it cannot, and most of them remain unsuccessful (Loc. cit. Otero, 2008: 84).

However, upon his return, he claimed to be “very happy. I bring data and it is exactly of what they are, and should be. Nothing I have seen can compare to the Spanish Project (Loc. cit. Otero, 2008: 94).

The Museum´s programmatic lines were presented by Cossío at the International Conference on Education in London from August 4 to 9, 1884, a few months after his inauguration as director. In his intervention, which constituted the international public presentation of the Museum, he highlighted the main keys to understanding the purposes, orientations and scope of the new organisation. The newly appointed director stated that he intended it to be a pedagogical and not a school museum, whose main aim was to collaborate in training of teachers. For Cossío, the gradual transformation of primary education in Spain needed to be based on the professional competence of the teaching profession, both those who educated children, and those responsible for training future teachers in normal schools. The Museum also intended to influence the modernisation of the material conditions of the school, school premises and buildings, school furniture or teaching materials. At the same time, it would have a pedagogical library, publish a pedagogical magazine, establish relations with governments in other countries to promote the exchange of publications and materials, be aware of the state of Spanish and foreign schools, organise visits and trips by staff. Cossío added, in his speech at the London Conference, that the Museum should be “the gateway through which all the advances made in early education in other countries were introduced into Spain” (Cossío, 1884: 593).

Source: Francisco Giner de los Ríos Foundation, Free Institution of Education, Madrid (Guerrero, 2016: 55).

Figure 2: Manuel Bartolomé Cossío in London, August 1884. Photo by Goodfellow.

This essence of openness attributed by Cossío, to the Museum to contribute to the reception and dissemination of the advances of contemporary international pedagogy in Spain, was constant in his pedagogical thinking (Esteban, 1975). Fifteen years later, in a speech given at the National Assembly of Producers (Zaragoza, 1899), entitled “On reform of national education”, he would express himself in a similar fashion:

for all reform, internal or external, in programs, plans, methods, organisation, etc., there must only be one formula: do what other people do. It is useless and ridiculous to start inventing the thermometer. Our great mistake consists in having been left out of the general movement of the world and our only salvation is in entering the current and in adopting what other nations do. In teaching, as in almost everything else, we are an exception and we must stop being so (Cossío, 1966: 182-183).

Thus, the tendency toward international openness of Spanish regenerationism, promoted by the members of the ILE, would be constant, present both in its ideals and in the actions developed by the National Pedagogical Museum, as well as the relationships maintained throughout its existence, with the pedagogical museums of other countries that are still pending study.

The National Pedagogical Museum and educational renewal in Spain

Throughout the various stages and vicissitudes experienced during its almost sixty years of existence (García, 1985: 55), the Museum was characterised as being a living and dynamic organism, a research and teaching centre, a gateway to the reception, study and spread of international educational innovations, which contributed to the renewal and modernisation of primary education and Spanish pedagogy.

Teacher training

For Cossío, the transformation of primary education in Spain depended greatly on the dignification of the teaching profession. A teaching staff that should have appropriate remuneration and broad and deep cultural, professional and pedagogical training. The main mission of the Museum in these areas, consisted of cooperating with the normal schools in training and pedagogical updating of teachers. To this end, from the start of its activities in 1884 the Museum promoted courses and conferences on general culture and general and special pedagogy. As of 1894, these initiatives were strengthened with the setting up of two laboratories, areas for experimentation, innovation and training, which anticipated the creation of pedagogical institutes in Europe (García, 1987).

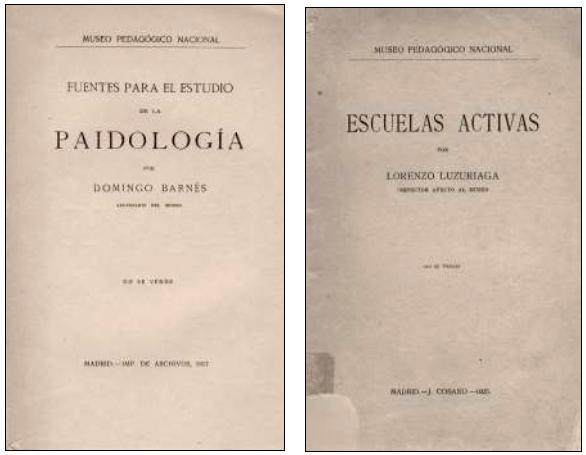

The Laboratory of Anthropometry and Experimental Psychology, also called Pedagogical Anthropology or Pedagogical Anthropology and Psychology, the first of its kind in Spain, led by Luis Simarro promoted the building of pedagogical knowledge on new bases. From there, courses in anthropometry and psychometry, physiological psychology, pedagogical psychology, pedagogical anthropology or experimental psychology would be promoted. The actions of the Museum generally and of this laboratory in particular, played a crucial role in developing research in the fields of pedagogical psychology, padiology, school hygiene or pedagogical anthropometry among others. Some relevant research fields would also be cultivated by important figures on the Museum Board such as Lorenzo Luzuriaga or Domingo Barnés Salinas both of whom would later be involved in republican educational policy (Moreno, 2019: 412-413).

The second laboratory-Physics and Chemistry, exerted notable influence on the modernisation of science education in Spain, both through training courses on experimental and laboratory strategies, and by becoming a reference centre for its innovative pedagogical orientations. The three figures in this field at the Museum, Ricardo Rubio from Botany, and Francisco Quiroga and Edmundo Lozano from Chemistry, would also deal with the central problems presented by science teaching and teacher training at different educational levels (Bernal, 2001: 63-99).

The entity of teaching activity developed by the Museum was soon recognised and appreciated both within Spain (Posada, 1904) and beyond its borders (Buisson, 1887: 1986-1987; Monroe, 1896: 390; Romano, 1897: 21- 29; Melon, 1898: 102). Some initiatives increased from 1911 due to the increase in its own training, as well as its collaboration with the Museum of Natural Sciences, the School of Higher Studies of Teaching, the Student Residence or the Board for Expansion of Studies. Such initiatives faded at the end of the second decade of the 20th century and laboratories would disappear. Following reorganisation of the Museum during the republican period, teacher training continued although it became merely testimonial (García, 1985: 115).

Courses were taught by Museum staff, ILE teachers, the University of Madrid or the body of primary-school inspectors. For conferences, figures from the world of science, culture and politics arrived, Francisco Giner de los Ríos, José Ortega y Gasset, Américo Castro, Carlos Navarro and Rodrigo, Juan Facundo Riaño, Emilia Pardo Bazán or Juan Valera, and renowned European pedagogues and psychopedagogues, including Alexis Sluys, founder of the Brussels Model School, or Édouard Claparède, promoter of the Juan Jacobo Rousseau Institute in Geneva.

The museum's training activities would reach teachers of different educational levels, mainly from Madrid, commissioned by their municipalities or councils, students from normal schools and the Central Normal School, intellectuals, university students and the general public. Testimonies by students who came from the provinces to Madrid to complete training at the Central Normal School, like Félix Martí Alpera (1875-1946) in the 1894-95 academic year, left a record of the imprint of courses and conferences by the Museum, for example, by Luis Simarro, Rafael Altamira or Emilia Pardo Bazán, of cultural visits with Cossío or Rubio to Madrid museums such as the Prado, the “artistic excursions” to Segovia, Guadalajara, El Escorial or Toledo, trips to natural environments, “geological excursions” or simply their admiration of Cossío himself (Martí, 2011: 127-139).

Renewal of school furniture and teaching materials

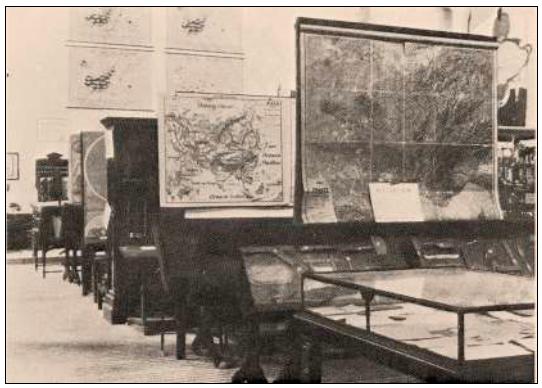

Originally located in a corridor and two rooms at the Veterinary School of the Central University of Madrid, the Museum received an extra boost following its final move to the Central Normal School of Teachers in 1886. Its rooms highlighted renewal of the school's material conditions. In these, school furniture and teaching materials were exhibited, noteworthty being natural sciences and geography, among others, from the houses of Fischer, Reimer and Chun in Berlin, Meinhold in Dresden or Suzanne and Delagrave in Paris, collections of handicrafts from the Swedish School of Nääs, calligraphic works, embroidery, etc. The furniture and material came partly from the Pedagogical Exhibition of the National Pedagogical Congress of 1882, and acquisitions and donations from publishers, merchants, industrialists, private individuals, educational establishments and national and official foreign organisations (Cossío, 1887b: 249-257).

Source: (Institución Libre de Enseñanza, 1985: 15).

Figure 3: Room at the National Pedagogical Museum. Madrid, 1909.

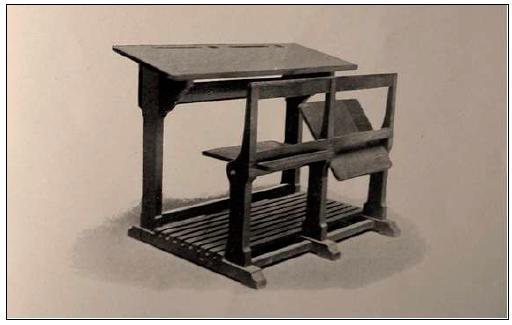

Right from its inception, the Pedagogical Museum (like Cossio himself on his travels) paid great attention to school furniture and became the reference point in this field in Spain. It contributed to introducing international hygienic and pedagogical innovations in our educational institutions. The design and construction of different types of school furniture made the Museum a centre of experimentation in these works. Likewise, its condition as a technical consulting body would, in this case, have political-administrative consequences. An opinion on school furniture requested by the General Directorate of First Education, would lead to the writing of the Technical Report on school furniture and decoration, of April 23, 1913, and be announced by the Ministry, by Royal Order June 30 of 1913 (Gaceta of July 11), setting forth guidelines on school furniture. In fact, this rule would make the table-bench from the Pedagogical Museum, the official model of desk used in Spanish schools (Moreno, 2005: 76-77).

Source: (Ministerio, 1913, Moreno, 2006: 804).

Figure 4: Two-person school bench-table model designed by the Pedagogical Museum.

In line with ideas by Cossío the Pedagogical Museum also placed large emphasis on teaching material to achieve material constructed and vivified by the teacher (Moreno, 2016: 415). In this case, the actions of the Museum were similar to those on school furniture. It was not limited to exposure of novelties by publishers and producers, but rather sought to analyse pedagogical usefulness, and influence the industry to improve production processes. The Museum was intended as a centre for experimentation of teaching material (Cossío, 1887b: 253-254 and 260). After remodeling in the Second Republic, with the new regulation of 1932, this field would be strengthened by allocating two of the three sections to teaching materials, under the responsibility of Regina Lago a teacher from the Normal School of Segovia, and Vicente Valls the primary education inspector in Madrid responsible for the pedagogical approach (García, 1985: 184).

Centre for information, study and pedagogical spread.

The Museum became the main educational information centre in Spain. Its library had two services, the reading room and the general circulating library, and another circulating service for children in the second decade of the 20th century. Between 1886 and 1901, the number of books increased by about 800 volumes on average annually, and in 1911 reached 16,225 volumes and 12,870 pamphlets. The library's holdings, initially nurtured by basically foreign bibliography, included pedagogical treatises, texts aimed at teacher training, as well as a large list of general and pedagogical periodicals published in Latin America ‒Argentina, Chile, Cuba or Uruguay‒, the United States and Europe ‒Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom‒ (Cossío, 1915: 198-201). Except for the National Library, the library at the Pedagogical Museum in Madrid attracted the largest and most diverse number of Spanish and foreign readers, mainly students from the Central University, normal schools, the Higher School of Teaching, professors or students sitting for Civil service exams for teaching bodies, with average daily consultations of over two hundred in the second decade of the last century. Its funds were made known through the Museum´s publication of the Bibliography and teaching material series, published in its entirety, between 1913 and 1927. The library was the only Museum service that lasted throughout its entire existence. The Museum´s advisory work was also seen in the field of reading through its choice of works for school libraries, circulating libraries for children and popular libraries distributed by the Board of Pedagogical Missions (García, 1985: 126-132).

The Museum was also a pedagogical study and dissemination centre. Rather than publish the planned Pedagogical Bulletin, it chose to promote a series of monographs based on Mémoires et Documents Scolaires type of the Pedagogical Museum of Paris, the Circulars of Information of the Ministry of Education of Washington or the Special Reports of the London Education Committee. It performed outstanding editorial work of its own from its inception in 1884 to 1934. Besides the aforementioned Bibliography and teaching material series, of nine titles, there was another on summer holiday camps with some thirty brochures, the memories of initiatives of this nature promoted by the Museum, which had introduced them and contributed to their configuration and promotion in our country (Moreno, 2009: 137-143), would also publish almost fifty titles. A first group of texts corresponded to studies by Domingo Barnés, Manuel B. Cossío, José Castillejo, Lorenzo Luzuriaga, Ricardo Rubio or translations by authors, such as Friederich Paulsen, Andrew F. West and Edward D. Perry, on systems and different educational levels, international statistics, teaching and the pedagogical renewal movement -new education, active school, etc.- in the world, particularly in Latin America, Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Holland, Portugal, United Kingdom or Switzerland. A second collection of works included innovative methodological proposals for teaching history, botany, physics or chemistry, by authors such as Rafael Altamira, Ricardo Rubio, Ignacio González, Ramiro Suárez or Edmundo Lozano. In turn, it edited reports on education in Spain, teaching material, school furniture, studies on the history of education, pedology, anthropometry, teacher training, special centres, Pedagogical Missions, school libraries, lectures by Rafael Altamira, Pedro Blanco, Manuel B. Cossío, Lorenzo Luzuriaga, Heinrich Morf or Emilia Pardo Bazán, or official Museum documents. Research promoted by the National Pedagogical Museum and consequent editorial production shows its outstanding role in the reception, study and spread of international innovating pedagogical currents, as well as its efforts toward the modernisation of education in Spain.

Conclusion

In summary, the National Pedagogical Museum constituted a centre of high pedagogical culture, an institution that developed essential mediation work between the detection and reception of new pedagogical trends, their introduction and adaptation, where appropriate, to the Spanish school and their dissemination among teachers. Through its teaching and research activities, it promoted scientific pedagogy and renewal of teaching methods, in accordance with psychological and pedological trends and advances in contemporary physiology, hygiene, medicine or sociology. Not only was it an entity limited to exhibiting collections of inert objects, but also a centre for testing and renovation of school furniture and teaching material that reflected on its pedagogical utility and influenced the cultural industries involved in producing school equipment. Its technical reports would have normative and practical consequences for the transformation of our educational institutions. It was both the main pedagogical information centre in Spain and a platform for creating and disseminating studies on some of the most relevant educational systems in the world, the international pedagogical renewal movements, as well as on Spanish reality. The National Pedagogical Museum represented the first bulwark of the Free Institution of Education and exerted huge influence on the modernisation of the Spanish school and education, followed by a period of decline that was overcome with remodeling during the Second Republic and which would later be suppressed by the Franco regime in 1941.

REFERENCES

BERNAL MARTÍNEZ, J. M. (2001). Renovación Pedagógica y Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Medio siglo de propuestas y experiencias escolares (1882-1936). Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

BUISSON, F. (Dir.) (1887), Dictionnaire de Pédagogie et d'Instruction Primaire. Paris: Librairie Hachette, 2 Vols. [ Links ]

COSSÍO (1884). Some account of the Educational Museum of Spain. En R. Cowper (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Conference of Education. London, 1884 (pp. 590-598). London: William Clowes and sons, Limited. vol. II. (Texto publicado en español en Cossío, M. B. (1887a). El Museo Pedagógico de Madrid. En Anuario de Primera Enseñanza correspondiente a 1886 (pp. 235-245). Madrid: Imprenta del Colegio Nacional de sordomudos y de ciegos). [ Links ]

COSSÍO, M. B. (1887b). Memoria sobre los trabajos del Museo 1882-1886. En Anuario de Primera Enseñanza correspondiente a 1886 (pp. 247-266). Madrid: Imprenta del Colegio Nacional de sordomudos y de ciegos. [ Links ]

COSSÍO, M. B. (1915). La enseñanza primaria en España. Segunda edición renovada por Lorenzo Luzuriaga. Madrid: Museo Pedagógico Nacional. [ Links ]

COSSÍO, M. B. (1966). Sobre reforma de la educación nacional. En M. B. Cossío, De su Jornada (pp. 181-190). Madrid: Aguilar. [ Links ]

ESTEBAN MATEO, L. (1975). Cossío, el «Museo Pedagógico Nacional» y su actitud comparativista europea. En Homenaje al Dr. D. Juan Reglà Campistol (pp. 391-403). Valencia: Universidad de Valencia. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, vol. II. [ Links ]

FERRER Y RIVERO, P. (1882). Revista de la Exposición pedagógica celebrada en Madrid en junio de 1882 por iniciativa de El Fomento de las Artes. En Congreso nacional pedagógico (pp. 421-450). Madrid: Librería de G. Hernando. [ Links ]

GARCÍA DEL DUJO, A. (1985). Museo Pedagógico Nacional (1882-1941). Teoría educativa y desarrollo histórico. Salamanca: ediciones de la Universidad de Salamanca. [ Links ]

GARCÍA DEL DUJO, A. (1987). El Museo Pedagógico Nacional y la formación del profesorado. En J. Ruiz Berrio, A. Tiana Ferrer y O. Negrín Fajardo (Eds.), Un educador para un pueblo. Manuel B. Cossío y la renovación pedagógica institucionista (pp. 149-175). Madrid: UNED. [ Links ]

GINER DE LOS RÍOS, F. (1927). Riaño y la Institución Libre. En F. Giner de los Ríos, Obras completas. Ensayos menores sobre educación y enseñanza (pp. 59-66). Madrid: Espasa Calpe, t. I. [ Links ]

GUERRERO, S. (Ed.) (2016). El arte de saber ver. Manuel B. Cossío, la Institución Libre de Enseñanza y el Greco. Madrid: Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos [Institución Libre de Enseñanza] / Acción Cultural Española. [ Links ]

INSTITUCIÓN LIBRE DE ENSEÑANZA (1985). Manuel B. Cossío y el Museo Pedagógico: [exposición]. Madrid: Institución Libre de Enseñanza, Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos, Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid. [ Links ]

JULLIEN DE PARÍS, M. A. (2017). Esbozo de una obra sobre educación comparada y series de preguntas sobre Educación. Edición y estudio introductorio de L. M.ª Naya Garmendia. Madrid: Delta. [ Links ]

LAWN, M. (Ed.) (2009). Modelling the Future. Exhibitions and the Materiality of Education. Oxford: Symposium Books. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15730/books.71. [ Links ]

MARTÍ ALPERA, F. (2011). Memorias. Edición y estudio introductorio de Pedro L. Moreno Martínez. Murcia: edit.um. Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia. [ Links ]

MELON, P. (1898). L’Enseignement Supérieur en Espagne. Paris: Armand Collin. [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DE INSTRUCCIÓN PÚBLICA Y BELLAS ARTES (1913). Material escolar. Dictamen técnico e instrucciones. Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra. [ Links ]

MOGARRO, M. J. (2003). Os museus pedagógicos em Portugal: história e actualidade. En V. Peña Saavedra (Coord.), I Foro Ibérico de Museísmo Pedagóxico. O museísmo pedagóxico en España e Portugal: itinerarios, experiencias e perspectivas. Actas (pp. 85-107). Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [ Links ]

MOLERO PINTADO, A. (2000). La Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Un proyecto de reforma pedagógica. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

MONROE, W. S. (1896). Educational Museums and Libraries of Europe. New York: Educational Review. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2005). History of School Desk Development in Terms of Hygiene and Pedagogy in Spain (1838-1936). En M. Lawn & I. Grosvenor (Eds.), Materialities of Schooling. Design - Technology - Objects - Routines (pp. 71-95). Oxford: Symposium Books. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2006). The Hygienist Movement and the Modernization of Education in Spain. Paedagogica Historica, 42 (6), 793-815. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230600929542. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2009). De la caridad y la filantropía a la protección social del Estado: las colonias escolares de vacaciones en España (1887-1936). Historia de la Educación, 28, 135-159. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2012). El Museo Pedagógico Nacional y la modernización educativa en España (1882-1941). En J. García Velasco y A. Morales Moya (Eds.), La Institución Libre de Enseñanza y Francisco Giner de los Ríos: Nuevas perspectivas. 2. La Institución Libre de Enseñanza y la cultura española (pp. 458-475). Madrid: Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos [Institución Libre de Enseñanza] / Acción Cultural Española, Vol. 2. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2016). La modernización de la cultura material de la escuela pública en España, 1882-1936. En M. C. Menezes (Org.), Desafios Iberoamericanos: o Patrimônio Histórico-Educativo em Rede (pp. 393-438). São Paulo: CME/FEUSP - CIVILIS/FE/UNICAMP RIDPHE. [ Links ]

MORENO MARTÍNEZ, P. L. (2019). El Museo Pedagógico Nacional. Un laboratorio para la formación del magisterio. En B. Alarcó (Coord.), La Nueva Educación. En el centenario del Instituto-Escuela (pp. 408-415). Madrid: Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos [Institución Libre de Enseñanza] / Acción Cultural Española. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2004). Adolfo Coelho: as súas relacións pedagóxicas e intercambio de ideas con Francisco Giner e Manuel B. Cossío. En Investigación e innovación na Escola Universitaria de Formación del Profesorado de Lugo (pp. 269-288). Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2007). Las primeras expediciones de maestros de la Junta para Ampliación de Estudios y sus antecedentes: los viajes de Cossío entre 1880 y 1889. Revista de Educación, núm. Extraordinario, 45-66. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2008). El viaje de Manuel Bartolomé Cossío por los Museos Pedagógicos de Europa en 1882. En I Encontro Iberoamericano de Museos Pedagóxicos e Museólogos da Educación. Santiago de Compostela, 20 ao 22 de febreiro de 2008. Actas (pp. 73-97). Santiago de Compostela: Museo Pedagóxico de Galicia. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2012a). La relación de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza con los movimientos pedagógicos europeos. En J. García Velasco y A. Morales Moya (Eds.), La Institución Libre de Enseñanza y Francisco Giner de los Ríos: Nuevas perspectivas. 2. La Institución Libre de Enseñanza y la cultura española (pp. 437-457). Madrid: Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos [Institución Libre de Enseñanza] / Acción Cultural Española, Vol. 2. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2012b). Manuel B. Cossío’s 1882 tour of European education museums. Paedagogica Historica, 48 (2), 197-213. [ Links ]

OTERO URTAZA, E. (2020). Las relaciones transnacionales en la creación del Museo Pedagógico de Madrid (1879-1889). En A. Barausse; T. de Freitas Ermel y V. Viola (Eds.), Prospettive incrociate sul Patrimonio Storico Educativo (pp. 179-202). Lecce/Rovato: Pensa MultiMedia. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2010.542763. [ Links ]

PELLISSON, M. (1911). Musées Pédagogiques. En F. Buisson (Dir.), Nouveau dictionnaire de Pédagogie et d'Instruction Primaire (pp. 1367-1376). Paris: Librairie Hachette, 2 Vols., 2ª ed. [ Links ]

POSADA, A. (1904). El Museo Pedagógico Nacional. Nuestro Tiempo, 2, 74-87. [ Links ]

ROMANO, P. (1897). Il Museo Pedagogico Nazionale di Madrid e l'insegnamento della Pedagogia in Italia. Torino: G. B. Paravia. [ Links ]

VIÑAO, A. (2004). Escuela para todos. Educación y modernidad en la España del siglo XX. Madrid: Marcial Pons. [ Links ]

Received: September 09, 2021; Accepted: November 11, 2021

texto en

texto en