Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-103

Dossiê 2 - Museus Pedagógicos: diálogos ibero-americanos

The Municipal Educational Museum of Lisbon (Portugal, 1883-1933): Journey and meaning of a renewing institution1

1Instituto de Educação, Universidade de Lisboa (Portugal). mjmogarro@ie.ulisboa.pt

The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa [Municipal Educational Museum of Lisbon] was inaugurated on 1 July, 1883, as part of an international affirming movement of similar institutions. Adolfo Coelho directed the Museum and played a key role in its organization; he designed its structure and selected and purchased its materials and books. As of 1892, the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, renamed the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa [Educational Museum of Lisbon] clearly illustrated the educational conceptions and orientations for a renewal of education that marked the pedagogical discourse of the time. It was part of the international modern education trend, which considered educational museums as fundamental mechanisms for the study of education and teaching and for the professional training of teachers. The reconstitution of its library confirms the Museum's place in the transnational network of idea circulation, containing works by renowned educational authors around the world and published in several languages.

Keywords: Educational museum; Circulation of education models; School culture

O Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa foi inaugurado em 1 de julho de 1883, inscrevendo-se num movimento internacional de afirmação de instituições semelhantes. Adolfo Coelho dirigiu o Museu e teve um papel fundamental na sua organização; ele concebeu a sua estrutura e selecionou e comprou os seus materiais e livros. O Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, a partir de 1892 designado Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa, ilustrava bem as conceções pedagógicas e as orientações para uma renovação do ensino que marcavam o discurso pedagógico da época. Ele integrava-se na corrente internacional da moderna pedagogia, que considerava os museus pedagógicos como dispositivos fundamentais para o estudo da educação e do ensino e para a formação profissional dos professores. A reconstituição da sua biblioteca confirma o lugar do Museu na rede transnacional de circulação das ideias, nela se encontrando obras de autores de referência da pedagogia mundial, publicadas em diversas línguas.

Palavras-chave: Museu pedagógico; Circulação de modelos pedagógicos; Cultura material escolar

El Museo Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa fue inaugurado el 1 de julio de 1883, como parte de un movimiento internacional de afirmación de instituciones similares. Adolfo Coelho dirigió el Museo y jugó un papel clave en su organización; elle diseñó su estructura y seleccionó y compró sus materiales y libros. El Museo Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, designado desde 1892 Museo Pedagógico de Lisboa, ilustra bien las concepciones pedagógicas y las orientaciones para una renovación de la enseñanza que marcó el discurso pedagógico de la época. Formaba parte de la corriente internacional de la pedagogía moderna, que consideraba a los museos pedagógicos como dispositivos fundamentales para el estudio de la educación y la docencia y para la formación profesional de los docentes. La reconstitución de su biblioteca confirma el lugar del Museo en la red transnacional de circulación de ideas, en la que se encuentran obras de autores de referencia de la pedagogía mundial, publicadas en varios idiomas.

Palabras-clave: Museo pedagógico; Circulación de modelos pedagógicos; Cultura material escolar

Introduction

The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa [Municipal Educational Museum of Lisbon] was inaugurated on 1 July 1883 and was a fundamental mechanism for the promotion of active teaching. Its creation was part of the educational renewal process, defended by a generation of educationalists, among whom Francisco Adolfo Coelho was noteworthy. In the context of the time, the creation of this museum must also be seen within the scope of the process of the emergence and affirmation of education sciences and in the dissemination of a modern educational culture. These ideas were a hallmark for the leaders of the city of Lisbon, which during the 1880s was experiencing a period of educational decentralization, thus creating the possibility for a remarkable set of initiatives for education - in addition to the educational museum, the Froebel magazine, the Froebelian-inspired kindergarten, the central and professional primary schools, etc. are noteworthy. In this process, the Museu Pedagógico played a strategic and significant role.

Adolfo Coelho directed and organized the Museu Pedagógico from its inception and also selected most of its materials, all the books held in its educational library and all the remaining compilations of the collection. The Museum’s organizational plan and various sections were also designed by Francisco Adolfo Coelho.

As of 1892, the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, renamed the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa [Educational Museum of Lisbon] clearly illustrated the educational conceptions and orientations for a renewal of education that marked the pedagogical discourse of the time at an international level. The Museum was a training institution, aimed at teachers and at the service of their professional development. Courses were held there, and educational and didactic material was acquired, tailored to the contexts in which they would be used. The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa was thus part of the international modern education trend, which regarded educational museums as fundamental institutions for the study of education and teaching -related issues and for the professional training of teachers. Through this museum, Lisbon positioned itself alongside other cities of reference, such as London, Toronto, St. Petersburg, Washington, Rome, Vienna, Zurich, Amsterdam, Brussels and Paris, which already had their own educational museums; for its part, it was more directly related to similar museums in Madrid and Rio de Janeiro. The reconstruction of its library is a confirmation of the Museum's place in the transnational network for the circulation of ideas, where the publications of renowned education authors in several languages (French, Portuguese, English, German, Spanish) are housed.

1. The role of Francisco Adolfo Coelho in the educational modernity construction process

The identity of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa is inseparably marked by the character at its origin, namely Francisco Adolfo Coelho, who was born in Coimbra in 1847 and died in Carcavelos, close to Lisbon, in 1919. He was a reference in Portuguese culture during the last quarter of the 19th century and early 20th century. However, his action in education is still relatively unknown as the few existing studies on this field of his activity focus on his development of educational thought in his publications on education and teaching (Fernandes, 1973).

The position attained by Adolfo Coelho in the Portuguese cultural scene was mainly asserted through his studies of literature and glottology, of popular traditions, anthropology, ethnography and ethnology. He was an expert in these fields and gave a fundamental contribution to their development. He introduced the new sciences to Portugal, and it was from an anthropological perspective that he addressed some of the problems of national education,2 also assuming a pioneering role in bringing new educational ideas to the country. His acknowledged importance on the part of his contemporaries is evident. The words of Marques Leitão, one of his peers, at around 1920 are particularly noteworthy:

it is not necessary to leave the house to seek the opinions of strangers. The principles disseminated today have already been examined with proficiency and careful research by erudite Professor Francisco Adolfo Coelho (...) [and reflected in] the organizational aspect of the former Rodrigues Sampaio school, to which this Professor gave a practical exemplification (...) Professor Francisco Adolfo Coelho, distinguished philologist, died on 9 February 1919. The country has lost one of its most cultivated teachers, who bequeathed highly valuable studies which earned praise from scholars overseas. (pp. 27 and 30)

Along with other fellow countrymen, he was at the origin of the famous Casino Conferences and participated with the conference A questão do Ensino [The Question of Education] (1872). Francisco Adolfo Coelho had previously experienced a childhood marked by hardship, following the death of his father. He studied at the secondary school of Coimbra and read Mathematics at the university of the same city. Disillusioned with the academic environment, the inquisitorial air of some of the teachers and the oratorical and "ornate" teaching (with which he would critically contrast the objective and scientific teaching of German universities), he abandoned his university studies and designed a training programme for himself, focusing mainly on German authors and learning the German language for such purpose.

‘He decides (...) on the difficult task of educating himself, exploring an atmosphere characterized by the positive spirit of science, by intellectual restlessness and by great synthetic and eclectic movements stemming from Comte, Spencer and German Romanticism. He frequently returns to late 18th century nationalism as a starting point for understanding the 19th century, namely in order to interpret the growing influence of Germanism. A rationalist and an intellectual, by engaging in self-education Adolfo Coelho adopts an 'intellectual education that is conducted at random, almost without method, beyond what the experience of failure teaches, feeling his way, so to speak.’ (Magalhães & Machado, 2003, p. 345)

His vast and multifaceted work condenses the strands of philologist, ethnographer and educationalist, and is rooted in the systematic pursuit of updated and scientifically consolidated information. In these three domains, he seeks to find an explanation for the national decadence, as well as a direction for the country’s resurgence, which would involve "a reform of mentalities driven by educational action" (Magalhães & Machado, 2003, p. 345). It is also in this sense that his positions on the total separation of the State and the Church (resisting the submission of teaching to religious ideas) and the defence and promotion of freedom of thought may be understood.

Source: Adolfo Coelho, Print, Alberto, in O Occidente, Lisbon 1880, vol. III, p. 184.

Figure 1: Francisco Adolfo Coelho

Francisco Adolfo Coelho was a professor at the School of Letters, where he taught Comparative Romance Philology and Portuguese Philology, and witnessed the transformation of this school into the Faculty of Letters of the University of Lisbon. He also practised teaching activities at the Escola Normal Superior de Lisboa and belonged to several secondary and higher education committees. He emerged as an ever-present, informed, critical and caustic participant in the intense educational debates that occurred during his lifetime, with a vehemence that was also reflected in his numerous newspaper articles and the controversies in which he was involved. However, his duties as Director of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa and of the Escola Primaria Superior Rodrigues Sampaio (both institutions created with his decisive contribution and strongly interconnected) are the focus of this paper.

Adolfo Coelho made a name for himself in academia in view of his studies, mainly in the fields of philology and ethnography, and was therefore proposed by a large number of intellectuals to teach in the School of Letters, despite not having a university degree. His merit was acknowledged by his peers (particularly Carolina Michaelis de Vasconcelos and her husband, Joaquim de Vasconcelos, who always supported him) and culminated in the award of an honorary doctorate by the University of Gottingen (Germany) in 1888.

In the dedication of a book written by António Sergio in 1914 and given to Adolfo Coelho, he states that he was "one of the very few men of true knowledge and high intellectual honesty that he had ever encountered in a country of charlatans” (Sá, 1978, p. 57).

2. The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa (1883-1892) and educational modernization in a period of educational decentralization

The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa was an important mechanism in the process of educational modernisation in Portugal, along with the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, both of which were directed by Adolfo Coelho. These institutions were created under the educational policy of the municipality of Lisbon in the 1880s, in the context of the decentralization of education (Mogarro, 2010, pp. 89-114).

The educational development project of Teofilo Ferreira gained a more prominent role when he became responsible for education in the City Council of Lisbon and, along with a group in which the presence of Adolfo Coelho was noteworthy, implemented a remarkable set of initiatives: the Froebel. Revista de Instrução Primária [Froebel. Primary Education Magazine] a fortnightly publication in Lisbon, 24 issues, between 21 April 1882 and 1884 [no month]); the (Froebelian inspired) kindergarten of Estrela (the first in Portugal); the Escola Central Municipal n.º 1, a graded school; the Lisbon Municipal Pedagogical Museum; the upper primary Rodrigues Sampaio (boys school, of a professional nature); and the Maria Pia school (girls school). In their diversity and complementarity, these educational mechanisms, were essential to the process of educational renewal and innovation developed by the municipality of Lisbon.

In the pages of the Froebel magazine, the concerns, action and thought of this group of educationalists are expressed. Some of its most important texts were written by Adolfo Coelho, namely articles on: The Life and Works of Frederico Froebel, School Savings Boxes, primary education in France, manual work in primary school and Technical education and general education. The texts published by Adolfo Coelho reveal the affiliation of his and his peers’ educational thought to the international renewal movement, electing Froebel as his main reference, while safeguarding the necessary adaptations to the case of Portugal. In fact, Froebel had been very much a part of Adolfo Coelho's educational trajectory as, in the 1870s, he had already received in Porto, "details from Carolina Michaelis of the practice of Froebel's educational exercises, which enabled him to defend and disseminate both his work and the kindergartens” (Sá, 1978, p. 52).

The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa was inaugurated on 1 July, 1883 (Froebel. 1883, p. 127), as had been announced a month earlier by Adolfo Coelho himself in the report submitted to the Junta Departamental do Sul [Departmental Council of the South] at the Portuguese Associations Congress: "The museum will be open to the public on 1 July, in very modest conditions and in a provisional, not very suitable facility of municipal school No. 6" (Coelho, 1883, p. 74), in Santa Isabel. The above-mentioned issue of the Froebel magazine highlights this inauguration, and also includes a detailed article on the Museum by Feio Terenas (Terenas, 1883, pp. 121-123). The press also reported the opening of the Museum:

The municipal educational museum was inaugurated yesterday [...]Mr. Rosa Araujo was chair, with Mr. Theophilo Ferreira, Councillor for education, on his right and Mr. Adolpho Coelho, Director of the museum, on his left. Once the session had begun, the chair called upon the illustrious educationalist Mr. Adolpho Coelho, who gave an eloquent speech explaining the aims and usefulness of this agreeable institution. His authoritative speech was received with great interest by the large audience that filled the room, and duly crowned with a warm round of applause. A great number of ladies attended this brilliant cultural occasion, and Mr. Henrique Midosi, Silva Amado, Oliveira Feijão, Estrella Braga, Sousa Telles, Feio Terenas, Ferreira Mendes, Caetano Pinto, Branco Rodrigues, Eduardo Dias, member of the school board; Pedro Monteiro, Martins da Fonseca, Costa e Sousa, José Antonio Dias, José Miguel dos Santos, the director of the school, and the municipal teachers were among the gentlemen present. Hundreds of people visited the museum rooms and were unanimous in expressing their admiration for the choice and good display of the exhibits. In the main room of the museum the material was displayed for education and teaching in the family, in the crèche, in the kindergarten, in the elementary and complementary primary school, in the professional schools, in the adult and further general or industrial training courses and in the teacher-training schools; the educational library, the first to be established in Portugal, and the archive comprising works by the pupils of the primary schools, documents relating to teaching in our country, etc. In another room school furniture models, expressly ordered overseas and chosen from the best catalogues of the United States and Europe, were on display. The battalion of municipal students (...) were the Guards of Honour. Open to the public. (Diário de Notícias, 1883, p. 1).

As far as Adolfo Coelho is concerned, the educational museum served as a fundamental support mechanism for active teaching, and its creation was part of the educational renewal process he so defended. The establishment of this museum should also be seen in the context of the time, when the emergence and affirmation process of education sciences was under way and the aim was to disseminate a modern educational culture. These ideas were a hallmark for the municipality of Lisbon, which advocated the education of the people and during the 1880s was experiencing a period of educational decentralization, thus creating the possibility for a remarkable set of initiatives for education. Within this process, the museum played an instrumental role of significant importance for education.

As of the beginning of 1883, Adolfo Coelho directed and organized the museum and chose much of its equipment, all the books housed in the educational library attached to the museum" (Terenas, 1883, pp. 121-122) and the rest of the institution's contents. In the words of Rogério Fernandes, "it [the Museum] was intended to support educational studies and was the first establishment of its kind in the country" (1973, p. 215). The organisational plan and the sections of the Museum were also designed by Francisco Adolfo Coelho.

Section A was dedicated to construction and furniture, containing architectural plans, elevations and models of crèches, kindergartens and nursery schools, shelters and rooms, elementary and upper primary schools, professional schools, public lecture halls, public and school libraries and school, public and educational museums. As for the furniture, the models for early childhood and general "school furniture" were considered. The scientific organisation of this sector reflected a concern with adapting the types of construction and furniture to the new teaching conceptions, which presupposed innovative educational and didactic techniques. The architectural space and furniture were meant to correspond logically and harmoniously to the most advanced educational concerns.

Section B consisted of the material for education and teaching. Focusing on the ontogenic development of children, their educational trajectory was mapped, beginning with «education and teaching before school», education in the family, in the nursery, in the shelters and in the kindergarten. It then moved on to documentation related specifically to school education and teaching - in elementary and upper or complementary primary schools, professional schools, adult and further general or industrial training courses of both sexes and in the teacher-training schools, in which particular didactic goals were considered such as: reading and writing, general instructive teaching, mathematics, cosmography, geography, natural history, physics and chemistry, physiology and hygiene, social history, technology, drawing, watercolour and modelling, music, horticulture and agriculture, manual work of both sexes, gymnastics and movement games. This section also contained documentation relating to courses and public conferences, as well as to the education and teaching of students with disabilities (who at the time were referred to as stutterers, deaf-mutes and idiots, for those who were intellectually challenged).

The library occupied Section C and was structured around educational studies. The first field, Pedagogy, began with its history: the foundations embodied in the works of the classics of pedagogy (originals and translations), followed by the general and specific histories of education and teaching, the monographs of educationalists and notable teachers, as well as the history of school institutions (universities, colleges and schools). The holdings also comprised the scientific basis of pedagogy, including works on physiology, human and comparative psychology (books by the most renowned psychologists and history of psychology), ethics (works representing the main former and modern schools) and social economy, the inclusion of which in the field of education sciences expressed a truly innovative perspective. The library also contained a set of works relating to systematic, general and specific theoretical and practical pedagogy, as well as contemporary (non-systematic) works on education and teaching. The organization of teaching and education at that time and in all the countries considered to be civilized was also covered, with a clear record of the need for the library to contain legislation, study plans and programmes, as well as statistical data. The library also housed mixed collections, educational and teaching magazines, documentation on school architecture and hygiene, children's books, elementary and auxiliary class books for the referenced educational establishments, as well as books for school and public libraries.

Finally, Section D contained the archive where documents relating to the various levels of education in the Portuguese education system were collected, with a particular emphasis on primary education, in addition to documents regarding public, school and municipal libraries, educational propaganda associations and also the works of primary school pupils in Portugal, especially those belonging to the municipality of Lisbon.

The plan that Adolfo Coelho had designed for the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa was advanced by Feio Terenas in the Froebel magazine and was a clear illustration of the educational concepts and orientations for a renewal of teaching defended by its author. The aim of its creation was to provide:

an exposition of facts for the study of comparative pedagogy ... [which would enable an understanding of] the current or remote means and processes of teaching and education, whether of one or many countries, of a given period or of an extensive era, is the same as having facts to which to apply observation, to read in the observations of others, and, consequently, to gather the best study elements. (Terenas, 1883, p. 122)

It was also the mission of the Museum to contribute to the training of teachers and other educational professionals. Thus, one of the initiatives taken by Francisco Adolfo Coelho was:

to offer a Froebelian pedagogy course in the Museu Pedagogico Municipal on Mondays and Fridays from 3pm to 4pm, exclusively for the staff of the Froebel school and children's classes (...) and for some alumnae of the Sunday courses, with the required equivalence, who wish to dedicate themselves to teaching. (Lisbon, City Council. Official Notice of the Director of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, to City Councillor... Teofilo Ferreira, dated 8 October 1883, Official Notice No. 19)

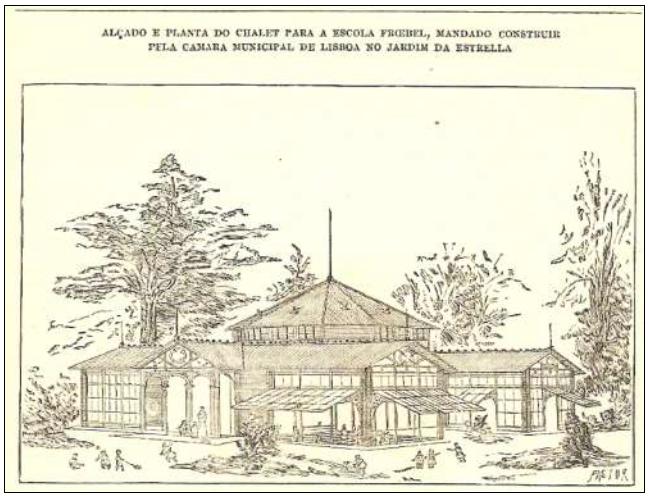

The Lisbon Kindergarten was the first Froebelian Infant School in Portugal and another symbol of Lisbon’s municipal policy throughout this decade. Solemnly opened in Passeio da Estrela on 21 April 1882, it was the highlight of the centenary celebrations of the birth of Frederico Froebel, along with the magazine named after the German educationalist. The municipality of Lisbon aspired to creating a Froebelian - inspired kindergarten, which had been expressed by the City Council at the time of the three hundredth anniversary of the death of Camões, in 1880 (City Council of Lisbon, 1880, p. 315). A new impulse would be given to this idea by Teofilo Ferreira, as soon as he became responsible for education in the Lisbon City Council. The first infant school was housed in a sober and elegant chalet, built out of wood, painted green and consisting of classrooms and covered outdoor spaces. The building was designed by the technical department of the City Council of Lisbon under architect José Luís Monteiro.

The Froebel school was inspired by the education system designed by the German educationalist, aimed at the simultaneous development of children's physical and intellectual faculties. The enthusiasm and persistence invested in the construction of the Froebel school in Lisbon by Teofilo Ferreira and his group can only be understood in light of the knowledge they acquired from the international circuits. In 1880, Teofilo Ferreira participated in the International Congress of Pedagogy, held in Brussels, and remained abroad to visit schools in Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France. He was convinced that Froebelian-type institutions were needed in Portugal and his initiative fell within the scope of the European educational reality (Ferreira, 1883, pp. 141-142 and 256). This aspiration was in line with the interests of Adolfo Coelho, as demonstrated by his formative action.

Source: Froebel. Primary Education Magazine, n. 1, of 21/4/1882.

Figure 2: Elevation of the chalet for the Froebel School, commissioned by the City Council of Lisbon in Jardim da Estrela

In the Hispano-Portuguese-American Educational Congress held in Madrid in 1892, an unsigned paper was presented on this infant school. However, Bernardino Machado, responsible for the Portuguese division, attributed its authorship to Carlota Sofia de Brito Freire, Director of the Estrela kindergarten (Machado, 1898, p. 279). Early childhood education was presented, a decade after its emergence in Portugal, as one of the most significant aspects of the educational modernisation of the country and its capital.

The building of this school still exists today. In its early days, it consisted of four classrooms and a hall for the purpose of school exercises, playground and dining room, where the children had their meals. It was furnished with two long and very low tables, suited to the children's small stature. It was also equipped with a fountain for the children to wash their hands at mealtimes. The support facilities included a vestibule, storage room, 2 offices, toilets and a fenced outdoor space (Figueira, 2004, p. 43).

During his educational mission to Europe, namely to Portugal, in the late 19th century, Brazilian Luiz Augusto dos Reis visited the Lisbon Froebel School and described it enthusiastically, emphasising that the rooms "are very cheerful and admirably clean", quite airy - the building itself appears to be "entirely made of glass, such is its abundance of doors and windows, which are almost open to the ground" (Reis, 1892, p. 82). His appraisal confirms the suitability of the options taken for the location and construction of the infant school ten years earlier. He also praised the equipment, stressing the uniformity of the school furniture, with the desks and attached low benches of the Froebel system, suited to the age of the pupils, as well as the tables for meals, and the maps and objects required for the type of teaching in this school. This material was certainly part of that ordered by Adolfo Coelho in 1883, thus establishing a bridge with the educationalist's action in favour of Froebelian infant education. The appraisal of Luiz Augusto dos Reis (1892) was, therefore, particularly appreciated, in which he underlines the following:

I did not find in Spain, France or Belgium a kindergarten superior to the Froebel kindergarten of Estrela in Lisbon, either for its building, or for its neatness, or for the order and regularity of its work. This is what one could wish for in terms of usefulness, elegance and beauty. It is frankly this that I have to say. (pp. 83-84)

Augusto dos Reis also records sending the elevation and plan of this kindergarten in Lisbon to the Pedagogium, the educational museum in Rio de Janeiro, as well as some of the children’s works given to him by the Director.

Adolfo Coelho also prepared the inauguration of the Escola Primária Superior Rodrigues Sampaio, which equally fit into his conceptual framework and had been previously explained in 1883.

All the countries concerned with reforming their public education have understood that the key to reform lies in the creation or organisation of model schools where good teaching methods can be studied in practice. The municipality is planning to create a public school with manual work as preparation for learning, and one cannot fail to see in this project, carried out under good conditions, an important step towards solving the problem of technical education. (Coelho, 1883, p. 74)

The Escola Primária Superior Rodrigues Sampaio (which would change its name several times over the years) was inaugurated on 16 October that year. Francisco Adolfo Coelho was its headmaster and teacher and remained in office until 1915, having a fundamental role in the organization of this vocational school, namely in establishing the goals and curricular plan.

In 1885, the Lisbon City Council also created the Escola Maria Pia for girls. This school occupied a building in Largo do Contador-Mor, in Alfama, and its main objective was the emancipation of women through education, as stated in its first report; of an eminently practical nature, it sought to "initiate the teaching of productive careers in the country that can and should place women (...) under provisions pertaining to basic needs, enabling them to earn honest means of subsistence" (as may be read in the report of the Escola Maria Pia regarding the academic year 1885-1886). With these objectives, it offered 4 courses: manual work, typography, telegraphy and commercial bookkeeping.

For its part, the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio was housed in the building of municipal central school No. 6, along with the municipal museum. However, this building, located in Rua de Santa Isabel, n. º 25, did not have suitable conditions for the Museu Pedagógico Municipal and the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio to function, therefore, in September 1884, these institutions were transferred to another more appropriate building and rented by the City Hall, in Rua do Sacramento à Lapa, n. º 25 and 27. The building subsequently underwent adaptation and restoration, forcing the closure of the Museum for a year until its reopening again in August 1885.

Despite being distinct institutions, the school and museum had been created and inaugurated a few months apart, shared the same director and were housed, until 1892, in the same building - in this coexistence, many resources were most likely shared as were also the activities, functions and human and material resources.

The Museum's Visitors' Book (which will also have been the school's) received the signature of Francisco Giner de Los Rios and Manuel Bartolomé Cossío on its first page, when they visited Adolfo Coelho in September 1883. From then on, they maintained close collaboration, also involving Bernardino Machado (Otero Urtaza, 2004, pp. 9-37).

As Director of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, Adolfo Coelho developed his educational activities in a persistent and continuous manner, expressing many of his concerns and educational ideas. It was the contribution of the German educational culture that constantly underlay his activity. This influence may be exemplified in two paradigmatic cases. In the first case, namely in 1894, he stated the following in relation to the management of programmes and the organisation of timetables.

It is also necessary [reforming the mathematics and natural sciences programmes] to make general changes to the programmes of the various subjects so that they correspond to each other. The timetables have reduced the number of lessons in most subjects, forcing some to last an hour and a half, which in terms of literary and scientific subjects is most inconvenient, as is acknowledged in the teaching practice of the most advanced countries. For instance, in Germany, in primary and secondary education, no lesson, except for drawing or manual exercises, ever lasts more than 50 - 60 minutes. (ANTT, 1894, Letter from the Director of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, [to the Inspector of Industrial Schools of the South District, Fonseca Benevides] dated 25 August 1894, NP 1436, no. 20)

He was also strongly critical of the fact that either textbooks did not exist or they were of very poor quality.

Another inconvenience we struggled with last year, one with which we have struggled since the school was created, is the lack of adequate books to facilitate pupils’ repetition, but above all to serve as a guide for teachers, putting an end to the vagueness of the syllabus (...)

12. Books. I will leave this very important point for the end. Adequate books for teaching, as it should be conducted in a school of this nature, are lacking, and it will be very difficult to make them, even when the bidder has the required scientific knowledge if he has not studied the problem from a pedagogical angle. (...) I have almost completely translated an excellent book from German, the plan and method of which are a true educational revolution, and it is designed for the teaching of the elementary principles of chemistry, physics and physiology, referred to by the Germans as Naturlehre, and the translation is being completed to better adapt the book to our teaching. This work has served as a guide for ten years for the teaching to which it refers in this school, and the experience has been extremely satisfactory, and it would be more so if we had it translated and printed, with the necessary modifications and additions, and if we had all the material required for its execution. (ANTT, 1894, Letter from the Director of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, [to the Inspector of Industrial Schools of the South District, Fonseca Benevides] dated 25 August 1894, NP 1436, no. 20)

Adolfo Coelho had a high notion of his responsibility and presented a plan for the edition and distribution of the manuals he was translating; this plan did not move forward, as there are no further details regarding this project. One aspect that is reinforced in his letter is the fact that German culture and pedagogy continued to be his major reference for educational issues.

An understanding of the significance of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio is again conveyed by the Report of Luiz Augusto dos Reis who, in 1892, described it as a model institution for professional education, "a special school (...) created by the City Council in 1883" and which was "directed by the notable teacher and distinguished writer and philologist Dr. Adolfo Coelho" (Reis, 1892, pp.73-74). In the portrait he draws of the Lisbon schools, this one provides a detailed and flattering description of the facilities, programmes and other dimensions of school life, focusing especially on the workshops. F. Adolfo Coelho gave Luiz Augusto dos Reis a collection of the pupils’ manual works, which the latter referred to as "magnificent":

The collection of manual works made by the pupils of that school is magnificent... In this collection there are iron works exercises; figures made of sheets of the same metal; polished pieces of iron and steel; iron sheet bindings; woodwork exercises; objects of common use; preliminary wood lathe exercises; tools and objects of common use made on the lathe.

Some of these works have been produced with the greatest care, revealing the great skill of the children who worked on them, and do great honour to the very useful and well-run Escola Rodrigues Sampaio. (Reis, 1892, p. 81).

Luiz Augusto dos Reis sent these manual works to the Pedagogium, the Brazilian educational museum, as well as the collection of works he had been given at the Froebel school.

In the same report, Luiz Augusto dos Reis refers to the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa (from whose designation the word municipal had already disappeared) as being connected to the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, "of which it is an integral part". He describes it as "good, but small, very small, for now (...) However, it has some good collections and the physics and chemistry cabinets are regularly supplied". He states that Adolfo Coelho had informed him that "it had just begun to function and that it could only be considered a trial" (Reis, 1892, p. 75). In 1887, the Museum was deemed by the City Council an "integral part" of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio and "its management subject to the Director of the same school" (Sanches, 2010, p. 32). For his part, Adolfo Coelho wrote in 1892 that "although [the museum] does not live up to such name, as its collections do not correspond to that title, it already has very valuable materials for school teaching.” (Coelho, 1892, p. 24)

It should be noted that the Museu Pedagógico clearly expresses the educational conceptions of F. Adolfo Coelho, which surpassed the restricted milieu of an enlightened and committed intellectual and bourgeois elite, which nevertheless fought for the progress and development of the country and the educational and cultural enhancement of the Portuguese population. Through this museum, Lisbon positioned itself alongside other cities of reference that already had their own educational museums, and it served as a vehicle through which a "fraternal" dialogue with similar institutions could be established, such as the educational museums of Madrid (through Francisco Giner de Los Rios and Manuel Bartolomé Cossío) and of Rio de Janeiro (through Luiz Augusto dos Reis).

3. Educational modernity and material culture in Portuguese schools: the case of Lisbon

F. Adolfo Coelho's up-to-date knowledge was also revealed in the supporting teaching equipment and materials, showing that he was up-to-date with the most recent material that appeared in the universal exhibitions and published by the specialized European companies.

For instance, F. Adolfo Coelho promoted and controlled the acquisition of Froebelian material. Along with his teacher-training activities, F. Adolfo Coelho arranged for the acquisition of suitable teaching material, namely Froebel's contributions and occupations with which he had been familiar since 1875. His correspondence with the Councillor for education illustrates this process: "I am sending you a list of the material which should be acquired as soon as possible for the Froebel school, the infant classes and elementary classes of the central schools". (Lisbon, City Council. Official Letter from the Director of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, to the Councillor ... Teofilo Ferreira, dated 8 October 1883, Official Letter no. 19). It should be stressed once more that Adolfo Coelho administered educational courses for the teachers of the Lisbon municipality (namely for the teachers of the Estrela kindergarten), a training practice he prioritized in his action.

Records later emerged of the materials acquired and the involvement and control of Adolfo Coelho in this acquisition process: "On the date of this letter, I am sending the objects ordered from Paris through Cruz e Companhia to the Froebel School. The Honourable Gentleman should check that all the requested objects have arrived and send me a receipt for them to be filed in this department" (Lisbon, City Council. Official Letter (copy) of the Ombudsman for Education of the City Council of Lisbon, João José de Sousa Teles, to Francisco Adolfo Coelho, dated 26 November 1883, Official Letter no. 574). The affiliation of F. Adolfo Coelho with the Froebel school is clearly evident in his concerns.

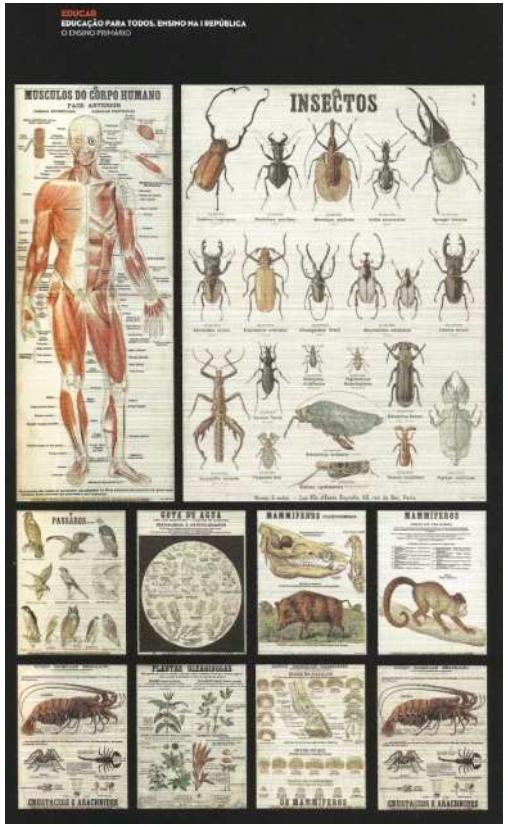

In the same year, Adolfo Coelho affirmed that the schools he had visited in Lisbon were beginning to display good school museums, without which an education reform would not be possible. These schools had collections of materials that were necessary for the teaching of the metric system, geometric shapes and parietal charts. Some of them were already equipped with a physics cabinet. The schools also had the «the natural history prints of the excellent school museums of Saffray and Deyrolle» (Coelho, 1883, p. 73).

Source: Educar - Educação para Todos. Teaching in the First Portuguese Republic. Primary Teaching (Proença, 2011, p. 33).

Figure 3: Set of parietal charts in the Portuguese schools, namely of the Musée scolaire Deyrolle (Exhibition“Educar - Educação para Todos”, 2011).

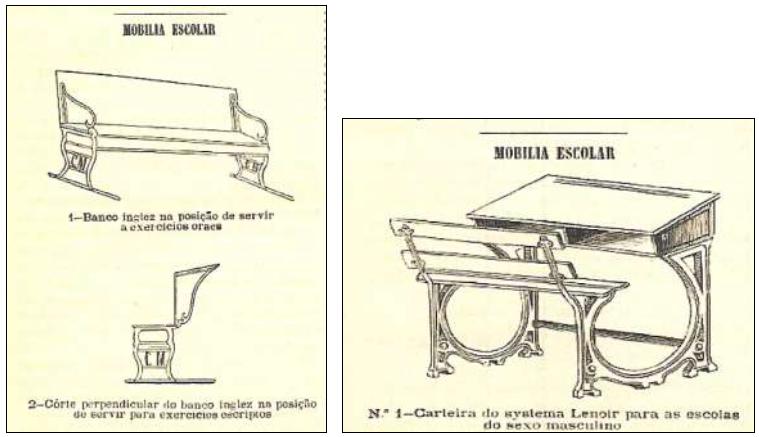

The Froebel magazine also reflected the concerns of this generation of educators with the application of the ideas on education and hygiene that dominated the debate in the educational field. Thus, the desk models illustrated below equipped the schools of Lisbon, as they were considered suited to the anatomy of the pupils.

Source: Froebel, no. 2, 15/5/1882

Source: Froebel , no. 3, 1/6/1882

Figure 4 and Figure 5 School desks (English bench and Lenoir system desk)

In his report of 1892, Luiz Augusto dos Reis described the teaching materials he had encountered in the schools of Lisbon, which also illustrate the concerns with active, experimental teaching, supported by modern, scientifically elaborated didactic materials:

Central School No. 1: physics cabinet; Saffray's museum for the lessons of things; 1 piano for singing exercises; trapezes, parallel bars and other tools for teaching gymnastics; 40 rifles with bayonets (for the school battalion); and a public library attached to the school;

Central School No. 2: library; physics cabinet;

Central School No. 5 and Escola Maria Pia: library; physics cabinet; chemistry laboratory; natural history museum; school museum; magnificent drawing and embroidery school works;

Central School No. 6: musical instruments; artillery pieces, rifles, bayonets, horns, etc;

Parish School: books, quills, pens, drawing paper, ink, pencils, etc.

The evidence of Portugal's integration in the process of production, circulation and appropriation of cultural and educational models is embodied in these educational materials that had already begun to equip the schools of Lisbon in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and were intended to convey modernity and active methodologies.

4. The path of the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa and the dispersion of its collections: in search of a lost library

As a product of the local educational policies of the City Council of Lisbon, the Museu Pedagógico Municipal suffered the negative consequences of the transfer of public education affairs back to central government in 1892. It lost its municipal dimension and became the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa that year. This period was followed by years of decline, characterized by fighting the lack of interest of the public authorities which, in turn, were experiencing difficulties with their staff establishment plan, and an irreversible period of decadence was set in motion. The museum’s materials were dispersed among various institutions over the course of a slow process that dragged on for years, as revealed by the research exemplarily conducted by Isabel Sanches (2010, 2016). However, the books retain the marks of having belonged to the original Library, as proven by the Museum's stamps.

Source: Books of the Museu Pedagógico belonging to the Historical Library of Education of the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Education.

Figure 6 and Figure 7 Stamps of the Museu Pedagógico

The museum's initial collection, constituted and organised by Adolfo Coelho, underwent a physical separation in that year of 1892: part of it comprised the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa, which was transferred to the (previously occupied) premises of Central School no.6. In the late 1890s, Adolfo Coelho, who was still directing both institutions, managed to secure the museum’s connection again to the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, thus appearing in several dissemination and information materials (Sanches, 2010, pp. 54-56). Once again, Adolfo Coelho had the two institutions in the same space, thus facilitating the use of materials in his educational activities.

Later, in 1919, the collections of the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa were transferred to the Escola Normal Primária de Lisboa (located in Benfica), as part of the project to create an educational museum, which did not come to fruition. Adolfo Lima refers to these collections as the "badly preserved specimen remains, " (Lima, 1932, pp. 118-119), which occupied three rooms. When, in 1933, the Biblioteca Museu do Ensino Primário [Museum Library of Primary Education] was created, directed by Adolfo Lima himself, the surviving materials of these collections that had remained at the Escola Normal de Lisboa were incorporated in the new Museum Library, which was housed in the same building as the teacher training school. In the 1980s, the teacher training schools were replaced by higher education schools and, in Lisbon, this process was accompanied by improvement works in the old Benfica building. The collections of the Biblioteca Museu do Ensino Primário [Library and Museum of Primary Education] were then transferred to the premises of the General Directorate of Basic Education, in the Ministry of Education. Some works bearing the stamp of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa remained in the library of the Escola do Magistério Primário de Lisboa [Primary Teacher Training School] and are currently part of the reserve funds of the Escola Superior de Educação de Lisboa [Lisbon Higher School of Education] (Toledo & Mogarro, 2011, pp.161-183).

The Instituto Histórico da Educação [Historical Institute of Education], created in 1998, partially treated and organized this collection, disseminating it among researchers. However, the Instituto Histórico da Educação was short-lived and became extinct in 2002. Since then, the collection of the former Biblioteca Museu do Ensino Primário has been under the tutelage of the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Education.

On the other hand, a significant part of the collections of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, which, in 1892, were integrated in the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, remained in this institution, following its trajectory until 1997, when this school was closed; on that date, the old library of the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio was donated to the General Secretary of the Ministry of Education. It is worth noting the donation of 24 books to the Academia Portuguesa de História [Portuguese Academy of History], at the latter's request, in 1938. The stability of this collection (far more numerous than that of the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa...) contrasts with the successive journeys across time made by the books of the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa, which migrated to various institutions. This bumpy journey may have given rise to greater losses than those recorded in relation to the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, and this was also reflected in the state of conservation of the works, which are in a greater state of decay (Sanches, 2010, pp. 98-99).

The custodial history of the Library of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa is reflected in the current location of the bibliographic documents, established by Isabel Sanches in 2010 and updated by the same author in 2016. Today the situation is as follows: Biblioteca Histórica da Educação [Historical Education Library] of the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Education and Science (MECSGBHE) - 855 works from the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio + 197 works from the Biblioteca Museu do Ensino Primário, totalling 1052 works; 32 works in the Escola Superior de Educação de Lisboa; 25 works in the Academia Portuguesa de História [Portuguese History Academy]; and 315 unlocated works. Thus a set of 1,424 works are considered (Sanches, 2016, pp. 15-20).

It should be noted that the Biblioteca Histórica da Educação of the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Education and Science (MECSGBHE) is the institution that holds most of the books and journals that belonged to the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, albeit in different collections. As previously mentioned, the documents that were transferred to the Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, to which we had access through the library of that school, with the exception of the 25 books transferred to the Academia Portuguesa da História in 1938, were those that suffered the least damage over the last 130 years. In fact, almost all the "unlocated" documents are works that, having remained in the Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa, had a much rougher journey, as they "travelled" between more institutions, thus possibly leading to more losses and negatively reflected in their state of conservation. (Sanches, 2016, p. 18)

5. The educational library of Adolfo Coelho in the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa: identity and meaning

The initial collection of the Library of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa was constituted by Adolfo Coelho in accordance with his educational interests and is a reflection of his critical thinking and priorities regarding the educational and teaching activity. The "identity of this collection" (Walker, 2009) is inextricably linked to the personality of this intellectual, who was one of the most informed and productive educationalists of his generation and who developed remarkable educational action in the transition from the 19th to the 20th century.

The research that served to replenish the library catalogue of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa shed new light upon this dispersed collection and the significance of Adolfo Coelho's thought and action (Sanches, 2010, 2016; see also Raven, 2004). In the reconstruction of this Library, Isabel Sanches crossed data and developed procedures that involved the original catalogues, bibliographical databases and cataloguing techniques, in a systematic search for the dispersed books (often resorting to signs of ownership, such as stamps). Furthermore, she made online searches in international reference catalogues when the physical absence of the works forced her to look for the books' data in other libraries, where there were still copies of the same work. Thus, it was possible to glean a clear overview of the first Portuguese educational library.

The library consisted of books by authors of various nationalities, containing the most important names in world pedagogy along with other texts of an educational nature. The languages of the 1,418 analysed titles are characterized by the predominance of French (436), followed by Portuguese (374) and then German (262), English (253) and Spanish (82); Latin (9) and Danish (2) are residual (Sanches, 2016, pp. 14-15),

The composition of the Library highlights the importance of "civilised countries", the expression used by Adolfo Coelho to refer to the most developed countries, which served as a reference and whose organisation of educational systems and teaching methods deserved to be studied and implemented in Portugal, by means of an adaptive process. He advocated this reform as fundamental for the progress and development of the country. In the constitution of his first educational library, he favoured the most well-known names in the pedagogy of his time and the themes he deemed most appropriate, attributing a strong tone of modernity - a genetic mark of his thought, of his educational action and of the nature of this first Portuguese educational library.

The publication dates of most of the works in this collection lie between 1870 and 1883 (around 1,110 titles), and were significantly concentrated in the years from 1880 to 1883 (around 646 titles; note also that around 132 titles did not have a publication date). These data confirm how Adolfo Coelho kept up to date with the most recent publications both in Portugal and abroad (Sanches, 2010, pp. 96-106; 2016, p. 15). Considering the structure of the library presented in the Froebel magazine in 1883, it was possible to establish a map of the works that composed the collection and synthesised the themes and problems to be mastered by Portuguese teachers and mobilised for educational situations. In this regard, the presence of works in the areas of "education and teaching before school", "music", "drawing, watercolour and modelling", "horticulture and agriculture", "manual work for both sexes", "gymnastics and movement games", as well as the "history of pedagogy", in which the reading of the great educationalists and "notable" teachers should be noted, along with the knowledge of the reference institutions are of particular relevance. The areas with "diverse, non-systematic contemporary works on education and teaching" are well represented (around 90 titles), as well as the "organization of teaching and education in our time, in all civilized countries, including legislation, study plans and programmes and statistics" (over 110 titles) and the "courses and public lectures" (almost 40 titles). The reports produced in the scope of different Universal Exhibitions were also present in this collection, bearing witness to the importance attributed to them by Adolfo Coelho, as a reflection of the nations' development and excellent sources of information on the technological progress in several areas, particularly in the field of education and teaching and the production of didactic materials (such as school museums). The main editorial collections identified by Isabel Sanches (2016, pp. 15-17) in this library express the nature of the themes and constituent contents.

Conclusion

The Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa played a key role in the educational modernisation of the country by assuming its teaching and teacher training reformist nature. This status is inseparable from the thought and action of Adolfo Coelho, who designed, organized and directed the Museum. In fact, his achievements take on greater meaning in the context of a generation of remarkable educationalists who accompanied this trajectory, however he played a unique and central role throughout the process. It was not a peaceful path; on the contrary, it was marked by conflicts, clashes of ideas, compromises and hypothetical agreements. However, this conflict allowed the Museum to assert itself as an educational institution of reference at the time, in articulation with the other institutions that were part of this renewal and modernization process.

The reconstitution of the Library of the Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa (Sanches, 2010, 2016) provides an insight into the nature of the Museum and its path, marked by the dispersion of books that travelled through various institutions following its closure. The other materials in its collections will have seen the same outcome, although it has not yet been possible to establish their "journeys" over time. The contents of the Library are closely aligned with the criteria and organisation defined by Francisco Adolfo Coelho in 1883, and in line with the functions attributed to this museum. This coherence between conception and implementation is surprising, both due to the solidity of the correlations that may be established and also to the broad range of themes and approaches included in the bibliographical set, which confirms Francisco Adolfo Coelho's enormous erudition and ability to update. One of the most obvious aspects is the influence of Germany on the thought and work of Adolfo Coelho, which is clearly reflected in the bibliographical and archival universe mobilised for this study. It is as if part of a German library and a set of teaching materials produced in Germany or France (or in other countries of reference) had travelled to us, condensing the main knowledge of the period.

The ability to place Portugal in the circuit of production, circulation and appropriation of the cultural and educational models produced in the civilized countries of the time was accomplished through Adolfo Coelho, who transported them to the Portuguese institutions under his direction. It was in these institutions that he made a personal appropriation of that knowledge, using it for his activity as a teacher and educationalist. Thus, the concept of "travelling library" (Popkewitz, 2005, pp. 3-36) makes perfect sense. However, the appropriation of this educational approach was not carried out in a solitary manner, but in the context of a social network to which Adolfo Coelho belonged, interacting with other educationalists of the time who, like him, were bearers of an educational modernization project for the country. Nevertheless, within this network he occupied a unique position.

In his self-taught path, Francisco Adolfo Coelho found in the German culture the main scientific foundations to build a conceptual framework marked by philological, ethnographic and educational studies, but it was in the educational field that he developed his practical achievements (Mogarro & Sanches, 2009). In fact, he argued that Portugal was not fatally decadent, hopelessly poor or necessarily backward and that, on the contrary, it could be regenerated through the reform of public education. This positive conviction, which, however, was not shared by all the intellectuals of his generation, was grounded on the scientific basis of his works and is inseparable from the pivotal position he occupied in the introduction process of the social sciences in Portugal and the educational modernisation of the country.

REFERENCES

ANTT - Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (1894). Carta do director da Escola Rodrigues Sampaio, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, [ao inspector das Escolas Industriais da Circunscrição do Sul, Fonseca Benevides] datada de 25 de agosto de 1894, sobre o trabalho desenvolvido na referida escola no ano lectivo de 1893-94, condições de funcionamento e algumas propostas de alteração do mesmo, ANTT - Ministério das Obras Públicas, Comércio e Indústria, Escolas Industriais, NP 1436, n.º 20. [ Links ]

Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (1880-1882). Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa. Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Ferreira, T. (1883). Relatório do pelouro da instrução da câmara municipal de Lisboa relativo ao ano civil de 1882. Lisboa: Tipografia de Eduardo Rosa. [ Links ]

Froebel. Revista de Instrução Primária (1882-1885), 24 números. [ Links ]

Coelho, A. (1883). A instrucção do povo em Portugal: relatório apresentado à Junta Departamental do Sul em sessão de 2 de Junho de 1883. In Congresso das Associações Portuguesas, 1, Lisboa, 1883 - Trabalhos complementares do Primeiro Congresso das Associações Portuguezas: realisado na Câmara Municipal de Lisboa desde 10 a 15 de junho de 1883: relatorios das secções da Junta Departamental do Sul. Lisboa: Typopgraphia Universal. [ Links ]

Coelho, A. (1892). O ensino primário superior. Lisboa: Imprensa de Lucas Evangelista Torres. [ Links ]

Diário de Notícias (1883, 2 de Julho), Lisboa, p. 1 [ Links ]

Fernandes, R. (1973). As ideias pedagógicas de F. Adolfo Coelho. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Ferreira, T. (1883). Relatório do pelouro da instrução da câmara municipal de Lisboa relativo ao ano civil de 1882. Lisboa: Tipografia de Eduardo Rosa. [ Links ]

Figueira, M. H. (2004). Um roteiro da Educação Nova em Portugal - escolas novas e práticas pedagógicas inovadoras (1882-1935). Lisboa: Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

Froebel. Revista de Instrução Primária (1882-1885), 24 números. [ Links ]

Leitão, C. A. Marques (1920). Trabalhos manuais educativos: instrução secundária, [S.l., s.n., ca 1920]. [ Links ]

Lima, A. (1932). Metodologia. Lisboa: Ferin. [ Links ]

Lisboa, Câmara Municipal. Pelouro de Instrução. Museu Pedagógico Municipal - Ofício do director do Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, para o vereador do Pelouro da Instrução, Teófilo Ferreira, datado de 8 de outubro de 1883, em que solicita autorização para efectuar um curso de pedagogia froebeliana, AML - EDUC, Gestão Administrativa das Escolas, B-040/01 (Ofício n.º 19). [ Links ]

Lisboa, Câmara Municipal. Pelouro de Instrução. Museu Pedagógico Municipal - Ofício (cópia) do Provedor da Instrução da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, João José de Sousa Teles, para Francisco Adolfo Coelho, datado de 26 de novembro de 1883, sobre o envio de material solicitado para a Escola Froebel, AML - EDUC, Gestão Administrativa das Escolas, B-025/01. (Oficio n.º 574) [ Links ]

Machado, B. (1898). O ensino. Coimbra: Tipografia França Amado. [ Links ]

Magalhães, J. & Machado, J. (2003). Coelho, Francisco Adolfo. In A. Nóvoa (Dir.). Dicionário de educadores portugueses (pp. 345-357). Porto: Edições ASA. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. (2003). Os museus pedagógicos em Portugal: história e actualidade. In V. P. Saavedra (Coord.). I Foro Ibérico de Museísmo Pedagóxico - O Museísmo Pedagóxico en España e Portugal: itinerarios, experiencias e perspectiva (pp. 85-114). Santiago de Compostela: Xunta da Galicia / Mupega - Museu Pedagóxico da Galicia. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. (2010). Cultura material e modernização pedagógica em Portugal (sécs. XIX-XX). Educatio Siglo XXI, Facultad de Educación. Universidad de Murcia, Vol. 28, n.2, pp.89-114. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. (Coord) (2013a). Educação e Património Cultural: escolas, objetos e práticas. Lisboa: Colibri/ IEUL. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. (2013b). Francisco Adolfo Coelho e o Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa. In A. C. V. Mignot (Org.). Pedagogium: símbolo da modernidade educacional republicana (pp. 281-306). Rio de Janeiro: Quartet/FAPERJ. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. (2020). O Museu pedagógico de Lisboa num tempo de modernização educativa e de circulação transnacional de ideias. In A. Barausse, T. F. Ermel, V. Viola (Ed.). Prospettive incrociate sul Patrimonio Storico Educativo / Perspectivas cruzadas sobre o Patrimonio Histórico Educativo / Perspectivas entralazadas en el Patrimonio Histórico Educativo (pp. 151-178). Lecce, Rovato: Pensa MultiMedia Editore. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. & Namora, A. (2013). Educação e Património Cultural: escolas, objetos e práticas, perspetivas multidisciplinares sobre a cultura material. In M. J. Mogarro (Coord). Educação e Património Cultural: escolas, objetos e práticas (pp. 9-44). Lisboa: Colibri/IEUL. [ Links ]

Mogarro, M. J. & Sanches, I. (2009). A presença de obras alemãs nas bibliotecas portuguesas: a acção pedagógica de Francisco Adolfo Coelho. In J. M. Hernández Díaz (Coord.). Influencias alemanas en la educación española e iberoamericana (1809-2009) (pp. 535-550). Salamanca: Globalia Ediciones Anthema. [ Links ]

Otero Urtaza, E. (2004). Giner y Cossío en el verano de 1883. Memoria de una excursión inolvidable. BILE - Boletín de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza, Madrid, n.º 55, octubre, pp.9-37. [ Links ]

Popkewitz, T. S. (2005). Inventing the modern self and John Dewey: modernities and the traveling of Pragmatism in Education. An introduction. In T. S. Popkewitz (Ed.). Inventing the modern self and John Dewey: modernities and the traveling of Pragmatism in Education (pp. 3-36). Nova York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Proença, M. C. (2011). Educar - Educação para Todos. Ensino na I República. Lisboa: Comissão Nacional para a Comemorações do Centenário da República - CNCCR, Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. [ Links ]

Reis, L. A. dos (1892). O ensino público primário em Portugal, Hespanha, França e Bélgica. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Raven, J. (Ed.) (2004). Lost libraries: the destruction of great book collections since Antiquity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Sá, V. (1978). Esboço histórico das ciências sociais em Portugal. Lisboa: Instituto de Cultura Portuguesa. [ Links ]

Sanches, I. (2010). Em busca de bibliotecas perdidas: a biblioteca do Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa. Dissertação de Mestrado, Departamento de Ciências Documentais (Orientação de M. J. Mogarro). Lisboa: Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Sanches, I. (2016). A Biblioteca do Museu Pedagógico Municipal de Lisboa. Lisboa: Secretaria-Geral da Educação e Ciência. [ Links ]

Terenas, F. (1883). Museu pedagógico municipal de Lisboa. Froebel. Revista de Instrucção Primária, n. 16, pp. 121-123. [ Links ]

Toledo, M. R. A. & Mogarro, M. J. (2011). Circulação e apropriação de modelos de leitura para professores no Brasil e em Portugal: Edições pedagógicas da Companhia Editora Nacional nas bibliotecas portuguesas. In M. M. C. Carvalho & J. Pintassilgo (Orgs.). Modelos culturais, saberes pedagógicos, instituições educacionais: Portugal e Brasil, histórias conectadas (pp.161-183). S. Paulo: Edusp/Fapesp. [ Links ]

Walker, A. (2009). The Library of Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753): creating a catalogue of a dispersed library. In World Library and Information Congress: IFLA General Conference and Council, 75, Milan. Disponível em: https://www.ifla.org/past-wlic/2009/78-walker-en.pdf. [ Links ]

1In this text, our previous publications on the topic are updated, namely in collaboration with other authors (Mogarro, 2003, 2010, 2013a, 2013b, 2020; Mogarro & Namora, 2013; Mogarro & Sanches, 2009; Toledo & Mogarro, 2011; Sanches, 2010). In particular, to a great extent the text resumes the ideas presented in Mogarro, M.J. (2020). The Museu Pedagógico de Lisboa [Educational Museum of Lisbon] in a period characterized by the modernization of education and transnational circulation of ideas. In A. Barausse, T. F. Ermel, V. Viola (Ed.). Prospettive incrociate sul Patrimonio Storico Educativo [Crossed Perspectives on Educational Historical Heritage] / Perspectivas entralazadas en el Patrimonio Histórico Educativo [Interwoven Perspectives on Educational Historical Heritage (pp. 151-178). Lecce, Rovato: Thinks MultiMedia Editore. It is a collection published in Italy in the form of a book. English version by Daniel Gregg. E-mail: danielgregg@flat62.pt.

Received: September 09, 2021; Accepted: November 11, 2021

text in

text in