Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-114

Dossier 3 - Personalized and community pedagogy in the ibero-american space (1950-1970)

Personalized and community pedagogy in Mexico: the first summer course in Guadalajara (1975)1

1Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil). Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa do CNPq. norbertodallabrida@hotmail.com

2Instituto Pierre Faure de Guadalajara (México). nbross@pierrefaure.edu.mx

This article aims to understand the first summer course animated by the French Jesuit Father Pierre Faure, which took place in mid-1975, in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico. Initially, it contextualizes the circulation of personalized and community pedagogy as proposed by Pierre Faure in Latin America, particularly in Mexico. The text focuses on the main pedagogic aspects explored by Faure in his lectures, which are the core of this course. In the light of Marta Carvalho’s historiographic perspective, the summer course is regarded as a strategy for the circulation of personalized and community pedagogy. The 1975 summer course was remarkable due to Father Faure’s pioneering presence in Guadalajara, which attracted educators from Mexico and other countries.

Keywords: Personalized pedagogy; Community pedagogy; Pierre Faure; Circulation

Este artigo se propõe a compreender o primeiro curso de verão animado pelo padre jesuíta francês Pierre Faure, ocorrido em meados de 1975, na cidade de Gualajara, México. Inicialmente, contextualiza-se a circulação da pedagogia personalizada e comunitária proposta por Pierre Faure na América Latina, particularmente no México. Enfocam-se no texto os principais aspectos pedagógicos explorados por Faure em suas palestras, que constituíram o cerne desse curso. À luz da perspectiva historiográfica de Marta Carvalho, considera-se o curso de verão uma estratégia de circulação da pedagogia personalizada e comunitária. O curso de verão de 1975 foi marcante devido à presença pioneira do padre Faure em Guadalajara, que atraiu educadores do México e de outros países.

Palavras-chave: Pedagogia personalizada; Pedagogia comunitária; Pierre Faure; Circulação

Este artículo tiene como objetivo comprender el primer curso de verano animado por el padre jesuita francés Pierre Faure, que tuvo lugar a mediados de 1975, en la ciudad de Guadalajara, México. Inicialmente, se contextualiza la circulación de la pedagogía personalizada y comunitaria propuesta por Pierre Faure en América Latina, particularmente en México. El texto se centra en los principales aspectos pedagógicos explorados por Faure en sus conferencias, que son el núcleo de este curso. A la luz de la perspectiva historiográfica de Marta Carvalho, el curso de verano se considera una estrategia para la circulación de la pedagogía personalizada y comunitaria. El curso de verano de 1975 fue notable debido a la presencia pionera del padre Faure en Guadalajara, que atrajo a educadores de México y de otros países.

Palabras clave: Pedagogía personalizada; Pedagogía comunitaria; Pierre Faure; Circulación

Introduction

Formulated since the 1940s by the French Jesuit Father Pierre Faure, the personalized and community pedagogy seeks to bring closer together Catholic educational principles and pedagogical matrices of the New Education movement. The Catholic Church had a long school tradition that had been founded by the Society of Jesus, whose reference was the Ratio Studiorum, updated when the Jesuits came back to the European scene in the early 19th century. Since the 1930s, Catholic education was defined by the papal encyclical Divini Illius Magistri, which emphasized the spiritual dimension in the comprehensive development of a human being. On the other hand, guided by a methodological interest, Father Faure took hold of several pedagogical matrices of the New Education, including those that clashed with Catholicism and advocated pedagogic naturalism (FAURE, 2008). Through Lubienska de Lenval, Faure came to know and became enthusiastic about the Montessori method and, although disagreeing with its Marxist bias and its Pavlovian psychology, he praised Célestin Freinet’s educational innovation, which was both individualizing and collaborative. Thus, the “new Catholic school” (SAVIANI, 2008, p. 300) created by Father Faure had a personalized dimension, but also a community one.

These two sides of the coin in personalized and community pedagogy are embodied in the work tools and didactic moments that Pierre Faure has created by means of educational essays carried out at the Center for Pedagogical Studies, installed in Paris and directed by him in the immediate post-war period. According to Dallabrida (2018, p. 330):

The first ones [work instruments] consist initially in programming - selection of contents and techniques used by the teacher to stimulate the student’s personal work, which must conform to the prescriptions of regions and countries, but must go beyond them -; work plan defined by the student; use of guidelines or forms for the student’s personal work, which does not exempt the teacher’s collective class; and course material, consisting of a classroom library or a library common to several rooms with books and documents, sensory-motor material, audiovisual material, as well as material for student self-control. The didactic moments (independent work, group work, sharing, synthesis and personal record, oral and written presentation, and continuous assessment) do not have a fixed order and can be made more flexible according to the student’s needs.

Through these didactic-pedagogic procedures, school work was not kicked off with the teacher’s classes, but with the role of a student who chose a study guide that was carried out without the chronological time division. The student research activity could be done with classmates and even provoke exchanges and discussions in small groups. Thus, there were no standardized tests nor grade failure, but the student who could not complete the program was offered an amelioration school group. In this learning mode, the teacher played a role of animator and guide (KLEIN, 1998).

Since the early 1950s, personalized and community pedagogy under continuing construction has been disseminated in several countries, particularly by Catholic circuits and, to a large extent, French ones. At the invitation of the Jesuit Father Artur Alonso, who headed the Catholic Education Association (Associação de Educação Católica [A.E.C.]), Pierre Faure came to Brazil in 1951 to deliver a lecture at the 4th Inter-American Congress of Catholic Education (ALONSO S. J., 1952). And, in mid-1955 and 1956, he came respectively to the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo to animate meetings with heads and teachers of Catholic schools who wanted to renew the traditional Catholic schooling, especially in primary education, which became known as pedagogical weeks (AVELAR, 1978). Thus, Pierre Faure kick-started the dissemination of his pedagogy in Brazil with a circuit of Catholic women’s congregations of French descent devoted to childhood schooling. In early 1959, Pierre Faure came to the city of São Paulo to prepare teachers from Catholic schools who wanted to deploy experimental secondary school groups - innovative essays in secondary education (DALLABRIDA, 2018). In addition to returning to Brazil almost every year to encourage teachers in pedagogic innovation, Pierre Faure published articles of an educational nature in the SERVIR ‒ Boletim da A.E.C., a fact that gave even more dissemination to personalized and community pedagogy.

In Hispanic-American countries, personalized and community pedagogy began to circulate only in the early 1970s. In Mexico, although Pierre Faure’s first interventions took place in Mexico City, it was in Guadalajara, capital of the state of Jalisco, that personalized and community pedagogy took root, especially through pedagogical sessions that, because they take place during the school holidays, were named as summer courses. Animated by Father Faure and supported by some of his French and Latin American disciples, these courses were held annually from 1975 to 1983, and each of them generated some written memory (SILVA, 2021). Thus, this article aims to understand the importance of the first summer course held in Guadalajara, in 1975, because it had verbal interventions of the creator of personalized and community pedagogy. To do this, its main source is the document produced by transcribing Pierre Faure’s lectures, entitled “Memoria del curso sobre Educación Personalizada” (CIPE, 1975). In its introit, the document states that “Dr. Faure’s spoken style has been intentionally kept, considering that this way the document will be more lively...” (CIPE, 1975, s.d., our translation). It is the official source for the 1975 summer course, which must be read in a contextualized and critical way as a document-monument.

The summer course held in Guadalajara in 1975 is regarded as a strategy for the circulation of personalized and community pedagogy. In the light of Carvalho’s (2003) historiographic reflections, the circulation of pedagogic models takes place through the displacement of people in other spaces and through the publication of printed material such as newspapers, specialized periodicals, and books, as well as movies and documentary films in various material supports. Therefore, it is neither natural nor linear, but marked by the interests and power games of individuals and/or social groups that have elective affinities. Finally, the text is divided into two parts: initially, there is a Latin American contextualization of the first summer course in Guadalajara, and then Pierre Faure’s lectures and their educational consequences are analyzed.

Hispanic-American circuits of Faurian pedagogy

According to Klein (1998, p. 103), “Anne Marie Audic, French, Maria Nieves Pereira, Spanish, and Celma Pinho Perry, Brazilian, accompanied Father Faure in 1972 to Mexico City to advise the first course for Mexican educators.” The first woman was Pierre Faure’s main French collaborator at the Paris Catholic Institute and author of a Ph.D. thesis on personalized and community pedagogy turned into a book (AUDIC, 1988); the second woman was the main disciple of the French Jesuit between Spain and Hispanic-American countries; and the third woman was one of the main responsible for promoting the pedagogical weeks in Brazil in the mid-1950s (AVELAR, 1978). This course in Mexico City attracted Catholic educators from other countries, such as the Jesuit Father Alfonso Quintana, professor at the School of Education in the Javeriana University of Bogota, and his brother in a cassock, Father Angel Maria Pedrosa, school head of the Society of Jesus in San Salvador - capital of El Salvador (KLEIN, 1998). Thus, from December 10 to 20, 1973, assisted by Maria Pereira Nieves, Pierre Faure was the animator of the “personalized education days for teacher training” (PEREIRA DE GÓMES, 1997, p. 49, our translation), held at the School of Pedagogy in the Javeriana University of Bogota.

To understand the circulation of personalized and community pedagogy in Mexico, it is worth considering the professional history of Maria Nieves Pereira, because she gained centrality as a pedagogic mediator. During her formative period, she was a pupil of Pierre Faure at the Paris School of Educators from 1966 to 1968 (PEREIRA DE GÓMES, 1997, p. 301), and then worked with her Jesuit and French master in the personalized education days, held from February 14 to 16, 1972, at the University of Murcia, Spain. There, Maria Nieves Pereira defended her doctoral thesis, under the title Educación personalizada: un proyecto pedagógico em Pierre Faure, which was published in book format in Mexico in 1976, and later translated into Portuguese in Brazil (PEREIRA DE GÓMES, 1997). In the mid-1970s, she moved to Mexico and became Pierre Faure’s main mediator in Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. Thus, Maria Nieves Pereira actively participated in moving the center of circulation and appropriation of personalized pedagogy from Mexico City to Guadalajara.

In the early 1970s, personalized and community pedagogy became known in Guadalajara. According to Bross Leal and Romero Garcia (2008, p. 9), “on July 18, 1973, in the city of Guadalajara, Jalisco, a group of parents and teachers met to legally establish a non-profit Civil Association, called the ‘Center for Research and Educational Planning’ (Centro de Investigación y Planeación Educativa [CIPE])” (CIPE, 1975, our translation). In the light of personalized and community pedagogy, the CIPE created the Pierre Faure Institute (see Figure 1), which started offering primary education and, later, secondary and pre-school education, being headed by the experienced teacher Rafael Paz, who gathered the teaching team and provided its preparation through an intensive one-week course in July of that year. During the 1973-74 school year, the Pierre Faure Institute’s teachers continued their ongoing training by means of a meeting from Monday through Friday in the afternoons, which had a didactic nature because it aimed to prepare the classes (BROSS LEAL and ROMERO GARCIA, 2008). At the end of the first school year, the head of the Pierre Faure Institute bet even more on teacher training, offering a two-week course in July 1974, with daily lectures on personalized and community pedagogy and a workshop on psychomotricity. About this unprecedented initiative, Bross Leal and Romero Garcia (2008, p. 24, our translation) affirm:

For the preparation of this course, a team was gathered under the coordination of the Institute’s head, Rafael Paz, who in turn invited Dr. Ma. Nieves Pereira and Dr. Begoña Ezcurra to shape the teacher’s work with children to see how the EPyC is put into practice. It was from the summer of 1974 on that the school teachers began to be advised by people outside the institution.

Source: Norma Cecilia Bross Leal’s personal archive.

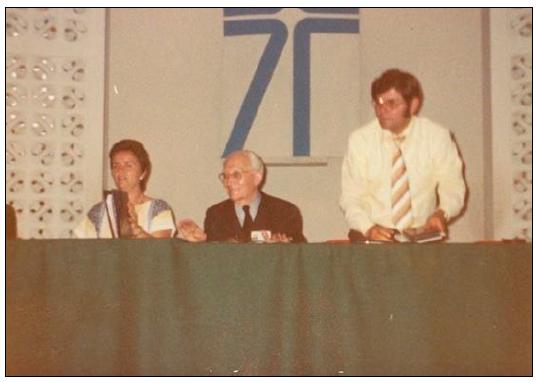

Figure 2 Pierre Faure to the center, besides Maria Nieves Pereira e Rafael Paz

At the end of the 1974-75 school year, the head Rafael Paz made efforts to enable the arrival of Pierre Faure himself to animate the 1975 summer course. This was a pioneering and encouraging fact, because the creator of the pedagogy used at the Pierre Faure Institute would animate a course from July 28 to August 8, 1975, with daily lectures, followed by time for questions, as well as observation sessions with students during school activity - as shown in Figure 2. This summer course attracted 395 educators from various states in Mexico, as well as from Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador, extending its scope of action to Central America. And it was made possible by the partnership between the CIPE and the Association Internationele pour la Recherche et l`Animation Pédagogique (AIRAP), created by Pierre Faure in 1971, which published the Revue AIRAP (CIPE, 1975). At the end of the summer course, Antonio Huerta, parents’ representative in the Pierre Faure Institute, said: “I have news to communicate to you, i.e. the AIRAP, through Pierre Faure, has given us its representation for Latin America and to begin with, we accept the responsibility of translating the journal [...]” (CIPE, 1975, p. 74, our translation). Guadalajara has therefore become the Latin American capital of personalized and community pedagogy.

Pierre Faure’s lectures

During the summer course held in Guadalajara in 1975, Pierre Faure delivered a series of lectures on personalized and community pedagogy. He began by underlining the puericentrism so dear to the New Education movement, stating that children are educators’ guides in the search for better educational attitudes and more adequate teaching methods. He asserts that the education needed by the contemporary world must be based on a pedagogy “where it is not repeated, nor recited, but rather it is a matter of assimilating personally according to one’s own rhythm, according to the manner of each one, not as the other assimilates it. It has been given the name of a personalized teaching that may guarantee the future teaching [...]” (FAURE, 1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 2, our translation). However, he draws attention to the fact that there are more and more initiatives to individualize school education, but personalizing it is a process of another nature, which involves respect for the uniqueness of each individual. Therefore, he rejects the stimulus-response mechanism of behavioral psychology and argues that, through external stimuli, each student responds in his own way and in an active and creative manner. In the key of personalized pedagogy, a teacher must move away from mechanical and external discipline and bet on the interiorization of the learning process that turns a student into a co-author in the learning process.

Not without reason, the French Jesuit suggests the prescriptions about Maria Montessori’s silence and the decisive contributions by Jean Piaget, which were already well known in the Western world. On the positions regarding the Swiss pedagogue’s learning process, Faure (1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 18, our translation), states:

For fifty years, Piaget worked on how to build what we call the child’s spirit, and therefore how to proceed for their mental development. The conclusions he has reached are very interesting and refer to the central issue of building mental structures. He believes that the child is being built by an ‘autogenesis’ of a grown child, i.e. by the body growth of an individual in relation to the entire species. Piaget is interested not in the group like the ‘Marxists,’ but in the person who belongs to the group. I do not say it this way, but I express it in other terms: “my first general result ‒ he says ‒ is that the importance of the active and constructive role of an acting individual, of the knowledge act of an acting individual, has become more and more strongly imposed, rather than the simple acquisition, the mere registration of data.

Based on Piagetian premises, Father Faure builds his educational personalism by refuting both the ideas that reduce human beings to genetic inheritance and those of a Marxist nature. Among the latter, he mentions the pedagogies of Célestin Freinet and Paulo Freire that, due to their socialist foundation, address the child in their social group, disregarding the uniqueness of each one.

However, Pierre Faure does not limit himself to theoretic discussions and concentrates his energies on the methodological operationalization of his pedagogic proposal, as Pereira de Gomes (1997, p. 15) correctly says: “he started by doing, not putting together theories.” In light of his faith in personalism in education, he claims that, despite starting from the same program, each student’s work plan is specific and must be strictly observed. He emphasizes the programming, which cannot be confused with the official program, aimed at teachers and administrators in each country, but “it is, on the contrary, what the teacher must do in his class, the topic he explains, how he is going to teach it, i.e. how he is going to do it in the classroom, how he is going to translate the official program, how he is going to choose the concepts. What their students have to buy [...]! (FAURE, 1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 24, our translation). It is the teaching operation of school contents that, according to Pierre Faure, must come from the simplest towards the most complex, observing, at the same time, the logical perspective, i.e. providing the chain of notions, the psychological ones, according to the biopsychological growth of students. Faure (1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 24, our translation) insists that the program must be clear and operational:

Each program notion must correspond to some work instruments or guidelines, or documents (depending on the theme). Thus, we allow the child to seek, to find, to understand, or to exercise what they have already learned; therefore, among the work instruments, application exercises should also appear, they may be the control that has been understood, sometimes even self-corrections of the same exercises can be added so that the instruments are there and the child knows what it is, to do, they know how far to advance or how far to go back in order to fix something that has been barely acquired; and so on throughout the year.

The work instruments play a strategic role in Faurian pedagogy, because they must contribute to the student’s self-control aimed at the search for new knowledge. In the lecture entitled “Check, not correct,” Faure (1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 43, our translation) says that “a second measure of self-control is the presentation of work to the teacher.” The teacher’s role is not only watching students, but also controlling them, i.e. monitoring their learning processes, so that they correct themselves. The teacher must be available for students to seek him out, in order to provide them with guidelines to seek solutions to their problems and doubts. In this direction, assessment is embedded in the learning process, so Pierre Faure recommends that teachers keep their students’ work plans as assessment documents for a school year, as well as in the medium term to show learning progress. And he insists that the assessment process does not focus only on knowledge, but also on skills in seeking knowledge in different supports such as the book and Pythagoras board. Finally, Faure (1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 44-45, our translation) completes his view on school assessment, by stating:

It is necessary to ensure that assessment is real, fair, and objective so that it allows giving grades or marks; even when we express them with a figure, that figure can be commented on, why it is possible, why it can be analyzed. If a child has really worked, their true assessment is the job itself.

These didactic-pedagogic devices concurred to encourage the interiorization of a learning process, so that external and coercive discipline was abandoned in favor of self-discipline inspired by Montessori. Not without reason, one of the lectures delivered by the French Jesuit was entitled “Normalization,” defined as “do things normally as they ask to be done” (FAURE, 1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 48, our translation), indicating that the methodology of personalized and community pedagogy should produce a behavior stemming from the students’ subjectivities. Thus, the personalized dimension of Pierre Faure’s pedagogic proposal ‘regulated’ - in the Foucaultian sense - the students, i.e. ruled the school population by inciting them to self-government (DUSSEL and CARUSO, 2003). Not without reason, the Faurian pedagogy is one of the most powerful contributions of the Catholic New School coming from France.

However, in light of a critique of the excessive individualization of Maria Montessori’s pedagogy and the Dalton Plan, Pierre Faure builds the community dimension of his educational project, so that to the Montessori’s motto “helps me do it myself” he added: “with the help of others” (AUDIC, 1988, p. 180). For many years, Pierre Faure’s educational initiative was known as personalized pedagogy, but he insisted that its community dimension was crucial. Thus, the book-synthesis by Faure, published in France in 1979 and translated into Portuguese in Brazil, was entitled Ensino personalizado e comunitário (FAURE, 1993), underlining the two aspects of school education that he proposed. In the 1975 summer course in Guadalajara, Father Faure addressed social education as an attitude that must be worked on at school so that it becomes something permanent in a student’s after-school life. Social education initially means realizing that others exist, but above all being aware that we are part of a social group, a school, a municipality, a nation, and that we must observe the other’s differences and help them through positive critique, as well as cheer for the success of others, just as in the case of sports (FAURE, 1975 apud CIPE, 1975). In this vision of social conscience, there is no reference to social inequality and the concentration of income in Latin America, which, at the time, was criticized by Liberation Theology. Marxist analysis was not only disregarded in the field of pedagogy, but also in analyzing the social world.

As a Catholic priest, Pierre Faure discusses children’s religious education, i.e. the faith education provided by teachers. In the light of personalized and community pedagogy, Faure (1975 apud CIPE, 1975, p. 31, our translation) states: “as always, it must be helping the child, making clear what is alive in them. First, helping the child to put themselves before God, in an attitude of respect, of adoration, attitudes that lead them to this adoration, which supposes an atmosphere of calm and silence.” This prescription is aimed at creating an atmosphere of interiorization among students, with a clear Montessori’s inspiration, which contributed to the personalization of education in the faith. On the other hand, Father Faure points out the importance of inciting students to liturgical practice, i.e. encouraging them to participate in masses, baptisms, Eucharist, confirmation, priestly ordination, among others, which work more on the external and community dimension of religious life. He highlights the first Eucharist, which, in addition to being a feast with relatives and neighbors, is a time for acknowledging the presence of Christ in each one’s life and acquiring content from the catechism. However, he criticizes the intellectualist nature in the Catholic liturgy, which was certainly an unfolding of the Second Vatican Council, which had made major changes in the liturgical rituals of the Catholic Church, particularly in the mass, which started being prayed in national languages and stimulated the believers’ participation.

According to the French Jesuit, faith education must be sought above all through readings about the divine intervention in the lives of men and women and, therefore, the school must make available to students books with Catholic content. First, the Old Testament, which tells the story of God revealing himself to the people of Israel and guiding their leaders; then, the New Testament, which tells the story of Jesus Christ and, at the same time, shows that God is trinity and one; finally, books pointing out that the Catholic Church continues the divine plan outlined by Christ. To materialize the learning of religious content, Father Faure makes some suggestions, starting from the creation of a documentation room, which has books, documents, and some program about the life of Jesus, the history of the people of God, and the growth of the Catholic Church, which must be seen from a geo-historical perspective. And it also points out the importance of making available to students in the documentation room or elsewhere a framework of current affairs on Christian life and the Catholic Church with press articles, as well as information about the gospel each Sunday (CIPE, 1975). Finally, after the challenging 1960s and the aggiornamento during the Second Vatican Council, the French Jesuit suggested the need to offer, in school education, a consistent and up-to-date religious education.

Final remarks

Pierre Faure’s lectures in the first summer course in Guadalajara focused on the foundations of personalized and community pedagogy updated by new social, religious, and educational trends. Not without reason, the theme of programming has a unique importance in Faurian pedagogy, because it is the operation that didactically takes hold of the official program defined by the Ministry of Education in each country, which must be built in a consistent and creative manner. By advocating collective teaching work and in-depth study, programming is the centerpiece of the methodology suggested by the French Jesuit, due to the fact that it is the basis of each student’s personalized work, a moment when learning actually takes place. In this process, a teacher is not made redundant, but takes on the role of a mediator, guide, instigator of a student’s search for knowledge and may even provide a moment of simultaneous teaching. In Faurian pedagogy, a teacher should not correct because the program and available material are expected to do this, but act in regulating - in a Foucaltian sense - learning as wished by the New School movement. On the other hand, in light of the criticism of individualizing pedagogical matrices such as the Montessori method and the Dalton Plan, Pierre Faure insists on the community dimension of his educational proposal, filtering the ideas of his fellow countryman Célestin Freinet. Thus, personalized student work can and should be carried out with collaboration of classmates and it even provides a moment to share the research studies with the whole class, being animated by a teacher.

It is worth placing the first summer course in Guadalajara in the movement to expand personalized and community pedagogy in Latin America. In Brazil, this pedagogic project was disseminated, in Catholic and French circuits, since the early 1950s, by Pierre Faure himself, through the publication of his articles in the SERVIR ‒ Boletim da A.E.C. and the realization of his pedagogic sessions that prepared teachers for Catholic schools at both primary and secondary levels. In the 1970s, when this irradiation in the Brazilian territory subsided, the Faurian pedagogic proposal gained ground in Spanish-speaking Latin American countries, especially in Colombia, Chile, and Mexico. In the latter country, the city of Guadalajara became the capital of personalized and community pedagogy, due to the foundation of the Pierre Faure Institute, as this is the place where the summer courses were held and for becoming the headquarters of the AIRAP in Latin America in 1975. Furthermore, this penetration of Pierre Faure’s educational ideas in Mexico - and in other Hispanic-American countries - had the decisive mediation of lay educators, particularly Maria Nieves Pereira and Rafael Paz, who deserve another historical inquiry.

REFERENCES

ALONSO S. J., Artur. Resumo do Relatório Geral da A.E.C. SERVIR-Boletim da A.E.C. do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, n.3, set.1952. p.10-15. [ Links ]

AUDIC, Anne-Marie. Pierre Faure S.J. 1904-1988: vers une pédagogie personnalisée et communautaire. Paris, Éditions Dom Bosco, 1988. [ Links ]

AVELAR, Gersolina Antônia de. Renovação Educacional Católica: Lubienska e sua influência no Brasil. São Paulo: Cortez & Moraes, 1978. [ Links ]

BROSS LEAL, Norma Cecilia. Colegio Pierre Faure. Informador.mx, 30 nov. 2012. Disponível em: https://www.informador.mx/Ideas/Norma-Cecilia-BrossLeal-Colegio-Pierre-Faure-20121130-0227.html. Acesso em 18 mai 2021. [ Links ]

BROSS LEAL, Norma Cecilia; ROMERO GARCIA, Bertha Margarita. Proyeto de formación permanente para los profesores de la primaria del Instituto Pierre Faure. Guadalajara, México: Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente, 2008. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Marta Chagas de. A Escola e a República e outros ensaios. Bragança Paulista: EDUSF, 2003. [ Links ]

CIPE. Memoria del curso sobre Educación Personalizada: “Verano de 1975” - Conferencias de Pierre Faure. Guadalajara: Centro de Investigación y Planeación Educativa, A. C., 1975. [ Links ]

DALLABRIDA, Norberto. Circulação e apropriação da pedagogia personalizada e comunitária no Brasil (1959-1969). Educação UNISINOS. São Leopoldo, n. 22, n. 3, p.297-304, jul.-set.2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4013/edu.2018.223.08 [ Links ]

DUSSEL, Inés; CARUSO, Marcelo. A invenção da sala de aula: uma genealogia das formas de ensinar. São Paulo: Moderna, 2003. [ Links ]

FAURE, Pierre. Ensino personalizado e comunitário. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 1993. [ Links ]

FAURE, Pierre. Précurseurs et témoins: d`un enseignement personnalisé et communautaire, Paris, Éditions Don Bosco, 2008. [ Links ]

KLEIN, Luiz Fernando. Educação personalizada: desafios e perspectivas. São Paulo, Edições Loyola, 1998. [ Links ]

PEREIRA DE GÓMES, Maria Nieves. Educação personalizada: um projeto pedagógico em Pierre Faure. Bauru, SP: EDUSC, 1997. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Demerval. História das idéias pedagógicas no Brasil. Campinas, Autores Associados, 2008. [ Links ]

SILVA, Daniele Hungaro da. Circulação da pedagogia personalizada e comunitária no Brasil e no México (1954-1983). 2021. Tese (Doutorado em Educação. Centro de Ciências Humanas e da Educação - Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, 2021. [ Links ]

Received: September 02, 2021; Accepted: December 10, 2021

texto en

texto en