Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-118

Dossier 4 - Transnational circulation of reading books and pedagogical manuals (between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century)

Adaptations and translations: primers and reading books “from Americans to Filipinos” (early 20th century)1

1Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Brasil). Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa do CNPq. mjwarde@uol.com.br

The domination of the United States over the Philippines, which began in 1898, was the first test of the model of cultural colonization that they would later adopt in other territories. It represents a modality of “transnational relationship” in which the parties entered in very unequal conditions. Once the main insurgent foci were annihilated, the US government began to invest heavily in the schooling of Filipinos by selecting and adjusting their educational standards. The article interrogates the US arguments for domination and focuses on reading books and primers translated and adapted for Filipino students as primary tools of the cultural arsenal used.

Keywords: Schoolbook; Philippines; United States

A dominação dos Estados Unidos sobre as Filipinas, iniciada em 1898, foi o primeiro teste do modelo de colonização cultural que adotariam a partir de então em outros territórios. Representa uma modalidade de “relação transnacional” na qual as partes entraram em condições muito desiguais. Uma vez aniquilados os principais focos insurgentes, o governo dos EUA passou a investir pesadamente na escolarização dos filipinos selecionando e ajustando seus padrões educacionais. O artigo interroga os argumentos dos EUA para a dominação e focaliza os livros de leitura e as cartilhas traduzidos e adaptados para os estudantes filipinos como ferramentas primeiras do arsenal cultural utilizado.

Palavras-chave: Livro escolar; Filipinas; Estados Unidos

La dominación de los Estados Unidos sobre las Filipinas, iniciada en 1898, fue la primera prueba del modelo de colonización cultural que adoptarían a partir de entonces en otros territorios. Representa una modalidad de “relación transnacional”, en la cual ambas partes entraron en condiciones muy desiguales. Una vez aniquilados los principales focos insurgentes, el gobierno de los EUA pasó a investir pesadamente en la escolarización de los filipinos, seleccionando y ajustando sus patrones educacionales. El artículo interroga los argumentos de los EUA para la dominación y focaliza los libros de lectura y las cartillas traducidos y adaptados para los estudiantes filipinos como herramientas primeras del arsenal cultural utilizado.

Palabras-clave: Libro escolar; Filipinas; Estados Unidos

Introduction

In the major American urban centers, between the late 19th century and the following years, prints circulated in public spaces carrying terms such as imperialism, chauvinism, belicism, fanatical patriotism, jingoism, as well as their antonyms. American historiography often refers to the period as “The age of American imperialism” or “American colonial period”, including in this “era” the invasion and subsequent annexation of Hawaii, in 1898, as one of the territories of the United States and, in the same year, as a result of the victory in the Spanish-American War, the dominion over Guam, Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico. That year, the president of the United States was William McKinley, in whose 1900 reelection campaign he was pressured by disputes between supporters and antagonists to defend expansionist positions. Assassinated in 1901, he was replaced by Theodore Roosevelt who gladly welcomed the adjectives of imperialist, chauvinist, jingoist 2, among others. In the memorabilia of the war between Spain and the United States, countless evidences of betrayals perpetrated by all sides are kept, but none stands out to those committed by the United States against local populations. They started with the argument of saving Cubans from Spanish atrocities and collaborating in the struggle for an autonomous government, free from secular Hispanic rule. They came up with the Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, by which Spain renounced any advantage over Cuba and, once having left the island entirely, the United States could occupy it, respecting all obligations established by international law. The Treaty also provided for the transfer by Spain to the United States of all the islands included in the so-called West Indies - notably Puerto Rico - and in the East Indies - Guam and the Philippines, the latter upon payment of 20 million dollars to Spain 3. But it was the domination of the Philippines that marked “the turning point of American territorial expansion” (HARRINGTON, 1935, p. 211; HARRINGTON, 1937). After establishing control over territories, populations and governments, maintained as zones of interference even when formally returned to their populations, the United States was accused by local people of the same barbarities that the Spaniards had previously been accused of (KARNOW, 1989).

The “Philippine matter”

In an interview given in 1903, the then President of the United States, William McKinley, presented a very personal, even intimate, version of those recent events.

I would like to say just a word about the matter of Philippines. I've been criticized a lot because of Philippines, but I don't deserve it. The truth is, I didn't want the Philippines and when they came to us, as a gift from the gods, I didn't know what to do with them. When the Spanish War broke out, Dewey4 was in Hong Kong and I ordered him to go to Manila and capture or destroy the Spanish fleet, and he had to do it; because, if defeated, he would have no place to reform on that side of the globe, and if the Gifts [Lords] were victorious, they would probably cross the Pacific and would devastate our Oregon and California coasts. And so he had to destroy the Spanish fleet, and he did! But that was all I thought then, when I realized again that the Philippines had fallen to our lap, I confess I didn't know what to do with them. I sought advice from all sides - Democrats and Republicans alike - but had little help. I thought that first we would just take Manila; then Luzon; then also other islands, perhaps. I walked through the White House night after night [...]; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that more than one night I have knelt down and prayed to Almighty God by light and guidance. And late one night it occurred to me like this - I don't know how it happened, but it happened: (1) That we could not return them to Spain - that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not deliver them to France and Germany - our trading rivals in the East - that would be a bad and shameful deal; (3) that we could not leave them alone - they were incapable of self-government - and they would soon have anarchy and disgrace worse than that of Spain; and (4) that there was nothing left to do but take them all and educate the Filipinos; elevate them, civilize and Christianize them, and, by the grace of God, do the best we can for them, as our fellow men, men for whom Christ also died. And then I went to bed and fell asleep; I slept soundly, and the next morning I sent for the Chief Engineer of the War Department (our cartographer) and told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States (pointing to a large map on the wall in his office), and there they are, and there they will stay as long as I am president! (McKINLEY, 1903, p. 64).

A significant portion of congressmen and businessmen enthusiastically welcomed the appropriation of the Philippines by the United States, under the most varied arguments, from the candid belief in "American exceptionalism" - which would prevent leaving the other "alone", immersed in the " incapacity for self-government” - even the most brazen interest in extraterritorial expansion for the purposes of commercial exploitation. Among the prominent names in favor of colonization was the magnate and congressman Marcus Alonzo Hanna, known as Mark Hanna, whose economic interests dispensed with the Methodist envelope adopted by his pupil McKinley in political matters. On the other hand, there were many protests against the expansionist initiative. Men and women from all life spectrum, for about two years, fought energetically for the United States to renounce the spoils of war. They did not obtain the desired results, but they created a tradition of fight that only intensified and deepened over time (CHATFIELD, 2020).

Boston was one of the first and most combative poles of the anti-imperialist fight; in this city, in November 1898, the first Anti-Imperialist League emerged, whose name was changed to the New England Anti-Imperialist League to distinguish itself from other leagues that were emerging across the country; in 1904, it reverted to its original name. According to Winslow (1899), in May 1899 the [New England] Anti-Imperialist League had over thirty thousand members. By the end of that year, around fourteen cities had formed their leagues-Boston, Springfield, Massachusetts, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and Portland. In October, with delegates from thirty states gathered in an anti-imperialist conference, those local organizations created a central league, the American Anti-Imperialist League, based in Chicago, which did not replace the onslaughts of associations spread across the country (HARRINGTON, 1935); LANZAR CARPIO, 1930; WINSLOW, 1899).

The diverse list of allies against US expansionism comprised prominent figures in the most different spheres of activity, such as: Jane Addams, Mark Twain, William James and Andrew Carnegie5, highlighted here only as a small sample. At the fifth annual meeting of the New England Anti-Imperialist League, held on November 28, 1903, philosopher William James expressed the values that united such disparate individuals under the same flag:

We used to believe that we were from a different clay than other nations, that there was something deep in the American heart that responded to our happy birth, free from that hereditary burden which the nations of Europe carry and which forces them to grow up by attacking their neighbors. Dream go away! Pure Fourth of July fantasy, dispersed in five minutes by the first temptation. In every national soul, there are potentialities of the most brazen piracy, and our own American soul is no exception to the rule. Angelic impulses and predatory desires divide our hearts just as they divide the hearts of other countries. It's good to get rid of hypocrisy and sham and get to know the truth about ourselves. Political virtue does not follow geographical divisions. It follows the eternal division within each country between the most animal and the most intellectual men, between conservative and liberal tendencies, jingoism and animal instinct that would govern things by main force and brute possession, and the critical conscience that believes in educational methods and in rational rules of law […]. The country has once and for all regurgitated the Declaration of Independence and the Farewell Address6 , and it will not immediately swallow what it is so glad to have spewed. It came to a hiatus. It deliberately pushed itself into the circle of international hatreds and joined the common wolf pack. It relishes the attitude. We take off our swaddling clothes, it thinks, and come of age. We are objects of fear for other lands [...]. (JAMES, 1903, p.25-26).

James' appeal to the moral conscience of his fellow citizens confronted more than "the Philippine question," for, after all, even when years later the right of self-government was conferred on some of the new possessions, the United States did not relinquish command either way. to maintain economic control - as in Cuba, for example - or to sustain, in addition to economic, military and cultural control, as in the Philippines. That's what James is all about. His country's government is pursuing an expansionist and xenophobic policy. It had beaten Spain by very unequal military means and had bought territories from her at modest prices - as it had already done with France; betrayed the local populations of those territories long involved in struggles for independence from Spain and in dreams of building a republic. The United States joined the fight to support them, but it did not take long to betray them. The intellectual elite of New England protested against what seemed to them to be a new perverse face of the politics practiced by the United States, a country so recent and promising in terms of democracy. His struggle aimed at preserving the values contained in the doctrines of the founding fathers that invoked the veto of governments to impose themselves on peoples and the obligation of the United States not to imitate the old methods of meddling in foreign affairs that Europe had historically adopted (HARRINGTON, 1935).

The reports of the military forces responsible for the government of the Philippines in the years that followed the Spanish-American war and, then, of the superintendents responsible for the schooling of Filipinos and for the subordination of current cultural practices in favor of a new, updated, Americanized, Western and Christian civilization, realize the priority interventions of the United States in the islands: health, basic sanitation and the (re)modeling of Filipinos through education.

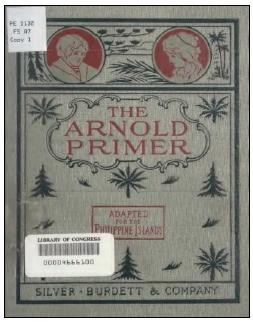

In the process of accelerated construction of schools and massive export of school artifacts, many American industries engaged in the manufacture of slates, desks, maps, alphabets, among other devices, as well as publishers mobilized in the production of notebooks and books intended for children, young and adults Filipino. Publishers such as the American Book Company and Silver, Burdett & Co, who were already engaged in this expansionist movement in Cuba, Puerto Rico and other territories, did not take long to contribute to the conquest of Filipino hearts and minds. The first waves they sent to the islands already included The Baldwin Primer and The Arnold Primer, respectively, intended for teaching reading and writing.

Pacifists and anti-imperialists like James did not mirror those practices. However, it is reasonable to assume that the United States was rehearsing at the time a style of domination that, despite being inaugurated and maintained by force, operated strategically through conviction, the subjugation of souls, enchantment and gratitude; cultural shaping practices, pacification of spirits as counterparts of the civilizational benefits offered by them: running water, sewage, eradication of pests, schools and a lot of religious preaching were arguments used with high persuasive potential. Tested internally with great success, they did not take long to prove effective externally: the image of an American soldier holding, in each hand, “schoolbooks and krags”7 has been used for more than a century as an emblem of that salvific imperialism.

The hypothesis adopted here indicates that the United States as a cultural amalgam produced both warmongering, xenophobia, contempt for the non-white, the non-Christian and managed anti-slavery, the defense of education, pacifism, diplomacy and the right to self-government of all peoples. It is not by chance that manifestations come from William James - within the limits of civility - about the belief in the “superiority of America” (JAMES, 1903). The also pragmatist, from the neo-Hegelian branch, George H. Mead offered arguments to that hypothesis. Interested in the topic of social identity and the constitution of the individual, Mead invoked the desire of every society for universality and, in order to achieve it, the development of mechanisms and institutions capable of guaranteeing the generalization and subjectivation of its principles and values. Or rather, every society seeks to include as many individuals as possible so that their conduct is guided by those principles, as well as seeks to ensure mechanisms that lead them to internalize those precepts with as much psychic rooting as possible.

Mead considered, however, that historically universality understood as generalization and subjectivation did not always exist. He identified, Hegelian and evolutionist that he was, three successive forms taken by societies or social groupings in an attempt to universalize themselves.

The first form would take place through the extinction or physical elimination of the other (society or social grouping); by the use of brute force. This would be the proper form of tribal societies. In the second form described by Mead, societies or groupings would no longer aim at elimination, but at subordination for the conservation of social groups or entire societies. The use of the principle of the subordination of the other in place of the principle of its physical elimination would be indicative of two important political manifestations for the social history of man: a) the origins of Imperialism and b) the sense of social universality.

Thus, two phenomena would stand out in the process of replacing elimination with subordination: i) alteration, on the one hand of the conditions for the formation of men's personalities; ii) on the other hand, through the mechanisms of subordination between societies or social groupings, relations of superiority and inferiority would be established: the dominant group seeks to convince the subordinate that it is effectively superior to it.

For Mead, the emergence of this second form would have given rise to the emergence of a third, which he calls "functional superiority", which finds its first and best example in the Roman Empire:

there is a sense of pride on the part of the Roman in his administrative capacity as well as in his martial might, in his ability to subjugate all the peoples of the Mediterranean and to administer them. The first attitude was that of subjugation, and then the administrative attitude appeared, which belonged more to the type I have been referring to as functional superiority [...] itself more than brute force (MEAD, 1972, p. 285).

The universalization of society or social grouping through "functional superiority", according to Mead, is "desirable and compatible" with the rules of democratic coexistence and it is in societies governed by this mechanism, therefore, in democratic societies, that individuals have better conditions to develop their personalities. Thus, for him, "functional superiority" would enable the best collective ordering and, therefore, would offer the best conditions for the individual's development because each individual "can [could] fulfill himself in the other through what is peculiar to oneself" (MEAD, 1972, p. 288)8 .

From Mead's understanding of the relationship between collective identity and individual identity, it is possible to derive: i) societies that build their identity are capable of expressing it in the form of a universal; that is, the uniqueness of a society is what makes it capable of attesting to itself (therefore, to its members) and to other societies its universality; ii) collective identity is realized and manifested in the institutions created by society, and it is through them that society exposes to its members and to other societies what can be called possible “consensus” that it has created over time; finally, iii) it is through social institutions that individual identities are constituted.

The definition presented by Mead of “institution” allows us to understand why he places the weight of social relations on it: “the institution represents a common reaction on the part of all members of a community in the face of a special situation” (MEAD, 1972). 261) On the contrary, however, of crushing individuals or annihilating their individualities, institutions can constitute self-conscious individuals, because they make individuals aware of the other. Institutions, in short, mediate the individual and the "generic" society or, to use a key category of his thinking: individual identity is constituted by the internalization of the "generalized other".

Thus, the institutions of society are organized ways of social or group activity, ways organized so that the individual members of society can act appropriately and socially by adopting the attitudes of others towards these activities. Oppressive, stereotyped and ultra-conservative social institutions - such as the Church - which, with their more or less rigid and inflexible anti-progressivity, crush or eclipse individuality, or inhibit any distinctive and original expression of conduct and thought of the people or individual personalities involved and subject to them, are undesirable products, but not necessary from the general social process of experience and behavior (MEAD, 1972, pp. 261-262).

Mead defends the thesis that democratic societies, governed by the principle of "functional superiority", offer the best conditions for the constitution of individual identities, as they are societies in which interactions within the scope of institutions allow the transit between values and principles that shape the universal identity of that society and the formation of society's members according to those same values and principles. One can complete the author's reasoning and state: to the extent that a society manages to (im)impose its universality on its members, it builds the conditions to impose its alterity/authority on other societies. Mead's arguments in favor of democracy serve as a justification for him to legitimize the empire that subordinates other societies through “functional superiority”. In it, there is a consistent argumentative game in which what is at the heart of American hegemony, born in the sameperiod of time in which its modern cultural identity was constituted in the United States: the “functional superiority” of the Roman Empire, its first example history, would find in the “democracy of America” the same conditions of flourishing. The legitimacy of internal subordination mechanisms is reiterated in relation to external members: this democracy is the expression of their “functional superiority” and can legitimately sustain the flourishing of the “American Empire” 9

A polite people exposed to the world

At the 1904 Exposition held in Saint Louis, Missouri, to commemorate the purchase of Louisiana, the United States reserved many spaces for the exhibition of the most varied subjects related to the Philippines. That year, the country was still involved in combating the insurrectionary movements that were breaking out across the islands. While the armed forces were killing, torturing and arresting the insurgents, the US government was interested in providing the world with evidence of the enormous anthropological and formative benefits that were being granted to Filipinos by the colonization inaugurated in 1899. As witness, they took around 1,200 native Filipinos, negritos, igorot, moros and visayans to be exposed (KRAMER, 1999; RYDELL, 1984). And what better occasion to expose the incorporation of the Philippines into the United States than the 100th anniversary of the purchase of Louisiana from the French for three cents an acre of land?10 That fair was the manifest destination on a global scale (RYDELL, 2003). It was a moment of epiphany for American progressivism and exceptionalism (WARDE, 2002).

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 offered its thousands of visitors the cultural, if unfinished, synthesis of what the United States was becoming: an amalgamation of civilization and barbarism, in unstable equilibrium.

That international exhibition held in Saint Louis, Missouri, ranked, as had never been done before, the sequence of peoples in evolutionary order - from the most savage to the most civilized; from the darkest to the most purely Caucasian; from shaman-worshippers to Christians - through a classification so competent that it would have delighted the forensic anthropologists, Spencerians, Lamarckians, and certainly Lombrosians who visited it. So detailed that it looked like the work of entomologists!

That was the great opportunity to drown out the voices of William James and all the critics of American imperialism. At the Saint Louis World's Fair, they would see Filipinos fraternizing with white Americans; they would see Filipinos willing to work; they would see their little children learning English in classes guided by modern pedagogy; all Americanized and, better still, all wanting to be Americans.

The organizers of the Saint Louis Exposition set aside 47 acres to reconstitute a reserve in which between 1,100 and 1,200 natives of the Philippine Islands represented their ways of life in their own homes. On the edges of the reserve, different tribes were grouped, which in themselves drew attention for their habits and ways of life; among these tribes, the exhibition showed that there are more or less 20 peoples and 100 tribal dialects, with clear lines of differentiation, depending on the degree of evolution reached.

The exhibition of Philippine education gained special attention from the organizers, since its first initiatives in 1902. The guidelines of the civil governor of the Philippines, William H. Taft, include all legislation to be brought together for the exhibition; the most complete description of the schools, the system of supervision and administration, the methods of instruction and training, the curricula and teaching plans; evaluation systems; teaching materials; textbooks and other schoolbooks; furniture and other equipment; museums, collections and libraries with the respective catalogues. In duplicate, photographs of the schools accompanied by the history of each one; school work; experiments; researches; teacher guidelines and much more (THE PHILIPPINE EXPOSITION BOARD, 1902)

Around forty of the “samar moros” from the island of Mindanao were exhibited; these were Muslims and considered “pirates”. For two and a half centuries they had made life miserable for the Spaniards and the natives of the Islands, because they looted villages, churches and took the Spaniards prisoner. The “negritos” came from the mountains near the Islands and were the aboriginal inhabitants; they were described as resembling black Africans, but smaller in stature, with an extremely small intelligence and a very primitive method of living (BUEL, 1904). The “Bagobos”, in some respects, were ranked as the most primitive and the most spectacular of the peoples of the Islands. They wore garments made of pearls extracted from shells; they were even more savage than the “Moros”, because they offered human sacrifices to the gods, more for cultural than religious reasons. Finally, three recently domesticated tribes - the “bontoc”, the “suyoc igorot” and the “tinguianes” - who were distinguished not only for being the most economically evolved but also for having more readily accepted the American government in the Islands and, therefore, they collaborated with him in a “civilized way” (WARDE, 2002; BUEL, 1904).

To fuel further amazement, Filipino dwarfs Juan (John) and Martina (Mary) Della Cruz, the two smallest adults known to the civilized world, were introduced. Juan was 29 years old and 29 inches; Martina was 27 inches and 31 years old. They were children of normal parents and had a normal 8-year-old son (WARDE, 2002; BUEL, 1904)11 .

Sanitizing souls and bodies, as it should be!

Once the Filipino rebellion against US domination was fiercely contained in 1902, the US government deployed in the islands began the creation of a public education system. In the same wave of colonization and at the same time, the creation of education systems in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal Zone and substantive reforms in the Hawaiian education system began. Not by chance, even though they were independent initiatives, they had many common elements, both in terms of guidelines and in terms of the apparatus used. The military government installed in the Philippines initially took care of the creation of schools and their provision; to the subject, dedicated part of their long reports - covering all aspects of local administration - addressed to the federal government of the United States, through the Philippine Commission 12.

This issue and others that were intended to support the Filipinos' path to civilization were of interest to the military, but with considerable relief they managed to get civilian help in organizing educational services as well as other sectoral services. In 1901, President William McKinley appointed William Howard Taft as civilian governor-general of the Philippines after the initial years of the War Department's rule. The tasks related to education and professional training were transferred to the civil governor; with it, the Philippine Bureau of Education was created. On August 23, 1901, an army ship transported 523 who became known as “thomasites” - American professors who were willing to leave the United States to save a portion of humanity, serving their homeland and God, in those distant islands of the Pacific13. The objective was to create and operate an “American” system of education in the Philippines, its degrees and modalities. To this end, they exported superintendents, teachers, curricula and study plans, teaching materials and school furniture, including bells, clocks, United States flags, number boards, terrestrial globes, maps of the Pacific Ocean, the world and the United States, blackboards, metric rulers, slate gallons, desks, slate and graphite pencils, paint gallons, shelves, among others. And many schoolbooks, including primers, reading books and grammar books in English

The Report of the Philippine Commission (UNITED STATES, 1901), corresponding to the period from December 1900 to October 1901, records the export to the Philippines of a batch of books published for the first grades of American schools, still without adaptations (Table 1) 14.

Table 1 Primer, Reading Books and Grammars exported to the Philippines between 1900 and 1901

| Report of 1900-1901 | Additional Information (MJW) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Title 15 | Amount received | Author | Publisher | Probable year of ed. used |

| Primer and reading books | Baldwin’s Primer | 60.000 | May Kirk [Scripture] | American Book Co. | 1899 |

| Baldwin’s First Year Reader | 10.000 | James Baldwin | - | - | |

| Baldwin’s Second Year Reader | 25.000 | James Baldwin | American Book Co. | 1897 | |

| Baldwin’s Third Year Reader* | 10.000 | James Baldwin | American Book Co. | 1897 | |

| Bass’s Beginners’ Reader | 10.000 | - | - | - | |

| New Educational Reader | 10.000 | - | - | - | |

| Thought Reader | 10.000 | Maud Summers | Ginn & Co. | 1900 | |

| Supplementary readings | Big People and Little People of Other Lands | 10.000 | Edward R. Shaw | American Book Co. | 1900 |

| Fifty Famous Stories Retold | 10.000 | James Baldwin | Franklin Publ. Co. | 1896 | |

| Health Chats with Young Readers | 10.000 | M.A.B. Keally | M. A. B. Kelly | 1898 | |

| Heart of Oak, Series nº 2 | 10.000 | Charles E. Norton Kate Stephens George H. Browne |

D. C. Heath Co. | 1895 | |

| Heart of Oak, Series nº 3 | 10.000 | Idem | D. C. Heath Co. | 1895 | |

| Little Nature Studies | 10.000 | John Burroughs | Ginn & Co. | 1895 | |

| Nature Studies, Davis | 10.000 | - | - | - | |

| [The story] Robinson Crusoe for Youngest Readers | 10.000 | Daniel Defoe Rebecca Hoyt Gordon Browne |

Educational Pub. CO. | 1898 | |

| Friends and Helpers | 10.000 | Sarah J. Eddy | Ginn & Co. | 1891 | |

| Grammars | First Steps in English | 10.000 | [Hans C. Peterson?] | [A. Flanagan Co.?] | [1902?] |

| Mother Tongue, nº 1 | 10.000 | Sarah L. Arnold George L. Kittredge |

Ginn & Co. | 1900 | |

| Mother Tongue, nº 2 | 10.000 | Sarah L. Arnold George L. Kittredge |

Ginn & Co. | 1900 | |

*Requested in August de 1901. Sources: UNITED STATES, 1901, p. 560-562 and another sources consulted by MJW.

The Fourth Annual Report of The Philippine Commission (UNITED STATES, 1904), for 1903, lists the books adopted at the Normal School in the capital, Manila, for teaching the English language without information if they adapted or not.

Table 2: English Books Adopted at Manila Normal School (1904)

| Report referring to 1903 | Additional Information (MJW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Text-books | Author | Publisher | Probable year of ed. used |

| First Year | ||||

| English | Fifty Famous Series Old Stories of the East Stories of Animal Life Fairy Stories and Fables |

- James Baldwin [Different authors] James Baldwin |

- American Book Co. - American Book Co. |

- 1896 - 1895 |

| Second Year | ||||

| English | Stepping Stones, nº 4 | Sarah L. Arnold Charles B. Gilbert |

Silver, Burdett & Co. | 1897 |

| Third Year | ||||

| English | Allen’s Grammar16

Stepping Stones, nº 4 |

- Sarah L. Arnold Charles B. Gilbert |

- Silver, Burdett & Co. |

- 1897 |

| Fourth Year | ||||

| English | Allen’s Grammar Stepping Stones, nº 5 |

- Sarah L. Arnold Charles B. Gilbert |

- Silver, Burdett & Co. |

- 1897 |

Source: UNITED STATES, 1904, p. 827 e and another sources consulted by MJW

In the following report, the Fifth Annual Report of the Philippine Commission (UNITED STATES, 1905) covering the year 1904, there is an annex where textbooks written or adapted for use in Philippine schools are listed.

Table 3: Schoolbooks written or adapted for the first grades of Philippine schools (1904)

| Title | Author | Publisher | Year of request |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Arnold Primer: Stepping Stones to Literature Series | Sarah Louise Arnold | Silver, Burdett & Co. | 1903 |

| A First Reader: Stepping Stones to Literature Series | Sarah Louise Arnold, Charles [B.] Gilbert | Silver, Burdett & Co. | 1903 |

| The Story of the Philippines | Adeline Knapp | Silver, Burdett & Co. | 1903 |

Source: UNITED STATES, 1905, p. 900.

According to the Fifth Annual Report, these schoolbooks, as well as other equipment, would make up “exactly” the same lot destined for schools in the United States: paper, pencils, blackboards, etc. in large numbers, as was done in American schools (UNITED STATES, 1905). For Philippine schools, however, books were intended not only in their original versions but also adaptations of books in English; furthermore, after many attempts, the leaders of the education system surrendered to the evidence: as the Moros were not willing to read, write and speak in English, they provided them with the same books, but “printed in Arabic characters, so that learn to read and write [at least] in their own language” (1906, p. 346), on the assumption that this learning would be a step towards the acquisition of the English language.

The resistance of the Moros, Igorots and some other inhabitants of the islands to the linguistic, and therefore cultural, domination of the United States fueled an avalanche of studies, but also of insults against these “precivilized” or “uncivilized” peoples, or even insubordinate to any form of civilization. Peoples who would have escaped, in every way, the evolutions through which humanity had already passed; part of them pagan; another Muslim part, which represented for the invaders an equivalent level of non-civilized, because non-Christian. All this the Exhibition of 1904 had shown abundantly; scholars had written about it, as had Stanley Hall in the second volume of Adolescence, first published in 1904, and Professor EB Bryan had testified before hundreds of his peers at the 1904 annual meeting of the National Education Association, held exactly at that Louisiana Purchase Exposition 17.

The failure to spread the English language to all the inhabitants of the Philippines was regarded as a serious sign of the non-universal reach of the American education system, a regrettable deficiency, considered the primary objective of the entire enterprise, clearly manifest in 1901 and repeated in all later reports.

Subjects of study for elementary schools may include reading, writing, grammar, arithmetic, geography, history, physiology, music, drawing, physical exercises, manual training and natural studies. Teaching in the English language should take first place. The teachers are prohibited from teaching any unauthorized subjects in public schools during legal school hours (p. 561-1901-2).

For Bryan, however, it was not the fault of the competent superintendents, the supervisors, or the devoted and well-prepared teachers. It was the fault of those tribes that could not even be called Filipinos (BRYAN, 1904).

In 1915, the Annual Report, referring to 1913-1914 (UNITED STATES, 1915), informs that all books for primary and intermediate schools, with the exception of Music books and most supplementary texts, had been prepared for Filipino schools. Specific books on commercial geography, colonial history, and economic conditions for high schools had been published, and chapters on the Philippines had been added to texts on physical geography, US history, and biology. All these books would have been adapted to the needs of Filipino schools and students; when compared to similar Americans, the result was favorable. Still, “a committee carefully evaluated the books in 1913 and indicated desirable changes and recommended adoption for a period of five years” (UNITED STATES, 1915, p. 286).

In the first lists of schoolbooks reported in the official reports of the US government in the Philippines, it is evident the presence of few authors responsible for more than three titles, including James Baldwin (1841-1925) and Sarah Louise Arnold (1859-1943); from 1903 onwards Arnold seems to have definitively supplanted Baldwin18. Both Baldwin and Arnold were introduced in the Philippines in versions created for school audiences in the United States, only to later gain versions adapted for Filipinos, almost exclusively in English, but not only. Pedagogical manuals for trained or in-training teachers also circulated in the Philippines, translated into Spanish and originally used in Cuba and other US possessions 19, in addition to that small portion of booklets and reading books printed in Arabic characters adapted for “rebels Muslims”.

Milligan (2004, p. 457-458), a scholar of the Philippines, Islam and ethno-religious conflicts, examines differences instituted by the Bureau of Education in the Philippines between schools for Moros and schools for other Filipinos, highlighting among the biggest, the exchange of the “most appropriate” instrument of instruction. In his words.

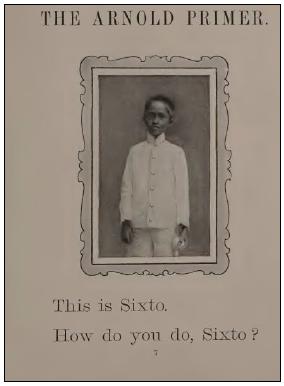

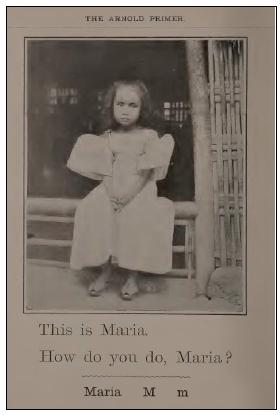

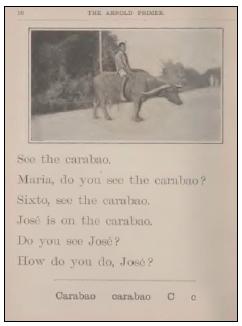

The first governor of the province of Moro, Leonard Wood, saw little value in the local languages, which he described as not displaying "characteristics of value or interest beyond a wild type of language". However, Superintendents of Public Instruction Najeeb Saleeby and Charles R. Cameron, as well as Governor Tasker Bliss, later favored teaching the children through their own languages. They believed that this was a more efficient and effective way to teach American ideas and to become literate. To that end, Saleeby created reading books in Tausug and Maguindanao using Arabic script. They contained a phonetic primer as well as an Arnold Primer translation formatted in the same way as the English version for ease of translation. Despite these differences, however, the underlying language policy was to make English, after all, the common language of the entire country (MILLIGAN, 2004, p. 458; MILLIGAN, 2020, p. 74) 20.

Sarah Louise Arnold's circulation in schools in the Philippines therefore went beyond her famous translated and adapted primer; she was also present through her manuals for teachers, translated or not, and through guidelines for the area of Home Economics, in which she was an expert, and instructions for Girl Scouts, given her leadership in this environment (WARDE, 2014; 2002). It did not take long to prevail over other authors of textbooks - notably James Baldwin - and pedagogical manuals, thanks to the professional and personal investment of the publisher Silver, Bardett & Co., and, to a lesser extent, of others such as Ginn & Co. they exercised control of the textbook market (WARDE, 2011) 21. Sarah Arnold's growing adherence to the analytical method also weighed in favor of Sarah Arnold's view of sentencing in the primer and the anecdotes in the reading books [readers], which, added to the investments of Silver, Burdett & Co., allowed her to increase the approximation of these pedagogical materials to the universe of target children's audiences through translations and “adaptations” provided by the publisher itself 22.

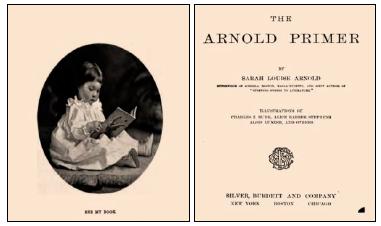

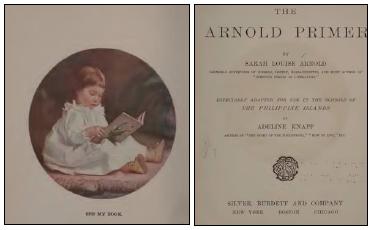

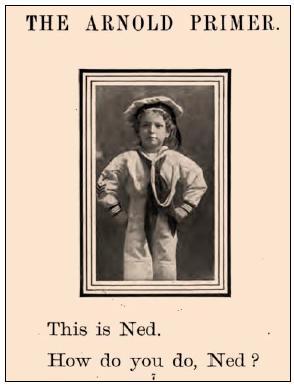

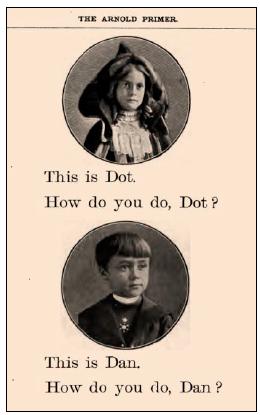

It doesn't take much to realize that The Arnold primer in English, adapted for a Filipino audience, is one of her most conspicuous achievements. Some images of the covers and inside pages of the 1901 edition for the United States and 1902 for the Philippines allow us to visualize what was given by “adaptation”. The two editions are repeated in terms of format, size, distribution of pages (128) and “lessons” (which follow one another without formal separations). In the 1901 edition, however, the first message, supposedly from the author, is addressed to children “to be read to them by the teacher”, while the 1902 edition, also unsigned, is addressed to the teacher. In both versions, the “lessons” end with a letter signed by Sarah Louise Arnold to the teachers regarding the steps followed in the booklet: first sentences, followed by the words that compose them and then initial letters common to the words - “carefully selected” - and the sounds of the words, warning that “words not [being] entirely phonic - e.g. “beautiful” - should be taught by sight, not sound”, so they would be better memorized, “as experience shows” (ARNOLD, 1901, p. 128; 1902, p. 128).

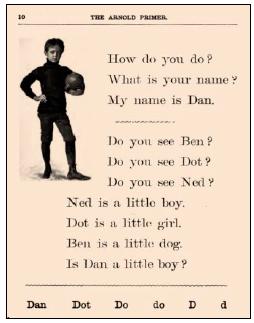

As in the first images above, most of the pages are fully repeated - images, phrases and words. In those pages where the “adaptations” are inserted, it is the images and words substituted that generate strangeness as they put in the place of a dashing and confident girl and boy, a sad, downcast girl and boy. On p. 10 of the American children's version, a boy named Dan is presented very well dressed, in a nice sports outfit, hugging a ball; on the equivalent page of the Filipino children's version, José appears on top of an animal; José is not exactly a boy and his features are not very friendly; however, he is not the central character on page 10: he is the carabao! An animal that reappears in the following pages as the maximum expression of the “adaptation” to Filipinos, of incorporation of the Filipino child's culture into the school message: it's not an ox, it's not a cow, it's not a horse, it's a carabao, the most Filipino of all animals!23 (WARDE, 2002).

A third factor contributed to Sarah Louise Arnold's success in America's school forays into the Philippine Islands: her intersection with Adeline Knapp, one of those 523 teachers from 1901 who became known as the "thomsatise", a name derived from of Thomas, the ship that transported them there (TARR, 2006)24 .

The men and women who made up the group did not share a common past; they came from different places; worked in different institutions; they came from families rooted in different religious, political and cultural aspects. Observed under a microscope, it is possible to find them developing specific, individualized pedagogical practices, even within the limits established by the leaders; but as individuals, they preserved singularities in the interaction with children, parents and so-called local communities. Even so, they were preserved in the memory of the American intervention as a cohesive and homogeneous group; heroic for the courage to face those people and their contagious diseases; worthy of astonished admiration for their willingness to dedicate some time of their lives to civilizing an “other” who was not so close. The mythology surrounding this group grew to the point that, over time, its name was extended to all other American teachers who worked in Philippine schools. Tarr (2006) tries to contain them in their proper dimensions: they were fewer in number than legend tells; they were human, all too human, each in their own way 25.

Little is known of Adeline Knapp, responsible for adapting Sarah Arnold's books for Filipinos and author of The Story of the Philippines, published in 1903 by Silver, Burdett & Co.; all adopted by the islands' public schools, as reported in the aforementioned Reports. There are few references to her name in educational circles; it appears as one of the most prominent among American writings on women writers and journalists, notably lesbian women who have stood out in the public space, including their oscillation, first in favor and then against the female vote26.

Born in 1860 in Buffalo, NY and died in San Francisco, Ca, in 1909, Adeline E. Knapp is said to have been a journalist and newspaper owner, writer, social activist, environmentalist, educator, suffragist and anti-suffrager. She projected herself on the San Francisco literary scene at the turn of the century, where she had moved, and on the political scene by writing in newspapers against child labor and the destruction of nature. Indeed, Knapp wrote about everything; including livestock, but expanded her notoriety as a national and even international journalist, recording in loco the annexation of Hawaii to the United States, which she defended under geopolitical arguments - defense of the coasts of her country - or under political-anthropological arguments - inability of Hawaiians to think for themselves what they wanted and what they needed after the overthrow of the reign then in force. Knapp thus expressed her position on the salvationist role of the United States in relation to backward peoples in the race towards progress; the same argument used by William McKinley to take possession of the Philippines.

Her vision of the “other” expressed in the case of Hawaii was even more forceful in relation to China, which she not only despised it but also mobilized her to participate in the movements to ban Chinese entry into the country, specifically in California. In the Philippines, she reaffirmed her prejudices, across the lines and between the lines of her 1902 The Story of the Philippines, tracing hierarchies between white and non-white tribes: the former, effectively Filipinos, and the rest, who arrived on the islands in lower evolutionary stages. Upon her return to the United States, Knapp already made explicit her abandonment of the suffragette cause. She gave testimony in the New York State Senate, participated in anti-suffrage movements and what she wrote on the subject ended up serving thesis against women's autonomy at home and at work (DAVIS, 2010).

In the same year of arrival to the Philippines, a group of thomasites decided to publish testimonies about the trip that would have lasted from July 23 to August 21, the date of arrival in Manila. The booklet was titled The Log of the “Thomas” and dedicated to the ship’s crew for “their high character and their kind and courteous efforts, which resulted in a most enjoyable voyage to our new home - the Philippines” (GLEASON, 1901, s/p). Only men took care of the edition and, with one exception, they signed the articles included in the booklet. The exception was “Miss Adeline Knapp” whose testimony, A Notable Educational Expedition, was inserted first 27.

There is another record, this one unsigned, that says something about the work that resulted in the textbooks Knapp wrote for Filipino students:

Thanks to Miss Adeline Knapp, former member of the 'San Francisco Call' [newspaper where she had work, MJW], for the excellent editorial on the mission of this great educational movement of which we are all a part. Miss Knapp will engage in literary work while on the islands and will collect material for a Philippine school history, a work in which she has been engaged for more than a year (GLEASON 1901, p. 50).

This note suggests that, perhaps, Knapp traveled with some training and, therefore, a license to teach, but she did not settle in the Philippines with this objective, but rather to gather information of a different nature about the life and habits of the inhabitants of the Islands. This is the thesis of Steinbock-Pratt (2013), one of the few historians to pay attention to Adeline Knapp in the field of education. Examining the advantages of travelling for single women, she recalls that after having published long after her stay in Hawaii when the monarchy fell in the 1890s, Knapp would have been willing to stay in the Philippines for a while planning to “write textbooks for Silver, Burdett Company, which could be used in the Philippines” (p. 103). The diary of Bernard Moses, the first Secretary of Education of the Philippine Commission, supports this thesis, as he tells that Knapp had come to him to ask what changes would need to be made to the school's "readers" to adapt them for use on the islands. Two months later, she informed Moses that she was sick and needed to return to the United States. She stayed for a short time, but it was enough to visit schools, socialize with teachers and students, talk to parents, and, above all, observe the daily habits of the population (MOSES apud STEINBOCK-PRATT, 2013). With these records, she wrote two books that she published for Silver, Burdett & Co., and certainly for the adaptation he introduced in Sarah Arnold's primer: the aforementioned The Story of the Philippines (1902), mentioned in the 1905 Report (see Table 3) and How to Live: A Manual of Hygiene for Use in the Schools of the Philippine Islands (1902), whose purchase or adoption is not mentioned in the consulted Reports; however, Steinbock-Pratt (2013) suggests that it has been effectively adopted in American schools on the islands.

It is still unclear what or who would have led to the crossing of Sarah Arnold (1859-1943) with Adeline Knapp. Just a year apart in age, Arnold and Knapp were both born on the same Atlantic side of the United States, where the former remained, while the other settled on the Pacific coast during her adult life. At the beginning of the 20th century, both had already achieved a reasonable reputation, at least in the American intellectual circles, through newspapers, books and other activities in the public sphere; however, nothing indicates, so far, that they belonged to the same sociability networks or created ties at a distance, which would not be unusual 28. With this, it is reasonable to assume that the relationship was mediated, at least at the beginning of the editorial procedures, by the publisher Silver, Burdett & Co.

Signs that the two schoolbooks were already ordered from Knapp by the publisher when she traveled to Manila are clear. On the one hand, because orders for textbooks had already become common practice in publishing houses such as Silver, Burdett & Co., especially since they practically controlled this market share using very advanced production, marketing and advertising practices; on the other hand, because the serialization of schoolbooks was already a consolidated practice in the United States. In other words, to risk little - in a segment that is very controlled by different agents and agencies - to earn a lot. It is not surprising, therefore, that The Story of the Philippines is the ninth book in a series called The World and its People composed of “geographical readers”.

But why assign such delicate tasks, such as the writing of these two books and the adaptation of Arnold's primer, to a renowned journalist who, however, had no experience in school work and, it seems, continued not having, considering the activities you dedicated yourself to in the Philippines? Who would have nominated Adeline Knapp for Silver, Burdett & Co., which allegedly introduced her to Sarah Arnold?

Final considerations

These questions will not be answered here. On the one hand, because they demand consultation of new documentary funds; on the other hand, because they do not belong to the central aims of this article, which must end with a return to its starting point. American school textbooks circulated in the Philippines - just as they circulated in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii... - in many versions: original, translated and adapted. These paths make up a modality of “cultural transnationality” or “transculturation” (PRATT, 1999) or, even, of “cultural translation” (BURKE; HSIA, 2009), quite different from those in which “choices between equivalents” or, more poetically, that involve “elective affinities”29. Here, a modality of “transnational relationship” was examined in which one of the parties chose nothing and the other decided everything, to the point where, looking in the mirror, the former no longer knew whether to see itself or the other with whom it was used had merged. But in the name of what did the United States impose itself on the Philippines? G. Mead would answer: in the name of its “functional superiority”. And Mead was a Democrat and on the left of the American liberal spectrum.

In the 1920s, Paul Monroe was called to chair a committee of teachers who, like him, were from Teachers College at Columbia University, to evaluate the Philippine educational system, for which they adapted tests and other instruments used with students in the United States. They arrived at similar results, now obvious, to those that were being obtained in other colonies existing at the time, not only in the United States: “the transplant” of entire educational systems does not give good results, because it ignores local conditions. In other words, the “adaptations” made were, at the very least, innocuous (PHILIPPINES, 1925). The first and biggest problem found among Filipinos: precarious command of the English language, although English has become an official language, constitutionally. From this came many others embarrassments. They also found that the local administrators who were then responsible for the government of the islands were not sufficiently competent and prepared for their duties. In a word, the Filipinos had not sufficiently Americanized themselves and the Philippine Islands together did not constitute the union of American states (PHILIPPINES, 1925)

REFERENCES

ALEXANDER, Nathan G. Unclasping the Eagle’s Talons: Mark Twain American Freethought, and the Responses to Imperialism. The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, n. 17, p. 524-545, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781418000099 [ Links ]

ARNOLD, Sarah L. The Arnold Primer. Especially Adapted for Use in the Schools of the Philippine Islands by Adeline Knapp. New York, Boston, Chicago: Silver, Burdett and Co, 1902. [ Links ]

ARNOLD, Sarah L. The Arnold Primer. New York, Boston, Chicago: Silver, Burdett and Co, 1901. [ Links ]

ARNOLD, Sarah Louise; GILBERT, Charles B. Stepping Stones to Literature. A First Reader. Adapted for Use in the Schools of the Philippine Islands by Adeline Knapp. New York, Boston, Chicago: Silver, Burdett and Co, 1902. [ Links ]

BALDWIN, James. Reader First Year. Adopted for use in the schools of the Visaya Islands by the Department of Public Instruction of the Philippines. Trad, Antonio Medalle e Edward P. DAVIS, Cynthia J. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography. Palo Alto, Ca: Stanford University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

BRYAN, E. B. Education in the Philippines. In: NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION: Journal of proceedings and addresses of the forty-third annual meeting held at St. Louis, Missouri in connection with the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Washington, D.C.: NEA, 1904. p. 100-104. [ Links ]

BUEL, James W. (ed.). Louisiana and The Fair. An Exposition of The World, Its People, and Their Achievements. Saint Louis, World’s Progress Publishing Co., 1904, v. IV. [ Links ]

BURKE, P.; HSIA, R. P. (orgs.). A tradução cultural, nos primórdios da Europa Moderna. São Paulo: UNESP, 2009. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL, Sydney A. The Illustrated Philippine Reader. New York: D. Appleton & Co, 1905. [ Links ]

CHATFIELD, Andrew The Anti-Imperialist Moment. Australasian Journal of American Studies, v. 39, n. 1, p. 81-100, Dec, 2020. [ Links ]

COLEMAN, Mary E.; PURCELL, Margaret A.; REIMOLD, O. S.; RITCHIE, John W. The Philippine Chart Primer. Philippine Education Series. New York and Manila: World Book Co., 1908. [ Links ]

COON, Deborah J. One Moment in tje World’s Salvation: Anarchism and the Radicalization of William James. The Journal of American History, v. 83, n. 1, p. 70-99, Jun, 1996. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2945475 [ Links ]

DAVIS, Cynthia J. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography. Redwood City, Ca: Stanford University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

FEE, Mary H. A Woman’s Impressions of the Philippines. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1912. [ Links ]

FREER, William B. The Philippine Experiences of An American Teacher: A Narrative o f Work and Travel in the Philippine Islands. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/198693 [ Links ]

GLEASON, Ronald P. (org.) The Log of the “Thomas”, July 23 to August 21. [S.l.: s,n,], 1901. [ Links ]

GOETHE, Johann W. As afinidades eletivas. São Paulo: Peguin, 2014. [ Links ]

HALILI, Maria Christine N. Philippine History. Manilla: Rex Book Store, 2004. [ Links ]

HARRINGTON, Fred H. Literary Aspects of American Anti-Imperialism 1898-1902. The New England Quarterly, v. 10, n. 4, p. 650-667, Dec., 1937. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/359930 [ Links ]

HARRINGTON, Fred H. The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898-1900. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, v. 22, n. 2, p. 211-230, Sept, 1935. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/1898467 [ Links ]

HILL, Mary A. Charlotte Perkins Gilman - The Making of a Radical Feminist. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980. [ Links ]

IIAMS, Charlotte C. Civic Attitudes Reflexted In Selected Basal Readers for Grades One Through Six Used In The United States From 1900-1970. 265f. Dissetation (Doctor in Philosophy Major in Elementary Education) - University of Idaho Graduate School, Moscow, ID, 1990. [ Links ]

JAMES, William. Address by Prof. William James. In: Fifth Annual Meeting of The New England Anti-Imperialist League. Boston: The New England Anti-Imperialist League, Nov 28-30, 1903, p. 21-26. [ Links ]

KARNOW, Stanley. In Our Image. America’s Empire in Philippines. New York: Ballentine Books, 1989. [ Links ]

KNAPP, Adeline. A Notable Education Expedition. In: GLEASON, Ronald P. (org.) The Log of the “Thomas”, July 23 to August 21. [S.l.: s,n,], 1901 [ Links ]

KNAPP, Adeline. How to Live: A Manual of Hygiene for Use in the Schools of the Philippine Islands. New York, Boston, Chicago: Silver, Burdett and Co, 1902. [ Links ]

KNAPP, Adeline. The Story of the Philippines. New York, Boston, Chicago: Silver, Burdett and Co, 1902. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Paul. Making Concessions: Race and Empire Revisited at the Philippine Exposition, St. Louis, 1901-1905. Radical History Review, v. 73, p. 74-114, 1999. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1999-73-75 [ Links ]

KRAMER, Paul. The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Paul. The Pragmatic Empire: U. S. Anthropology and Colonial Politics in the Occupied Philippines, 1898-1916. 1998. Dissertation (Doctor of Philosophy) - Department of History of Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, 1998. [ Links ]

LANZAR-CARPIO, Maria C. The Anti-Tmperialist League. The Philippine Social Science Review, v. III, p. 7-12, 1930 [ Links ]

McKINLEY, William. Interview with President McKinley [concedida ao General James F. Rusling]. Christian Advocate, v. 78, n. 4, p. 137, Jan 22, 1903. [ Links ]

MEAD, George H. Mind, Self and Society: from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972. [ Links ]

MILLIGAN, Jeffrey A. Democratization or neocolonialism? The Education of Muslims under US Military Occupation, 1903-1920. History of Education, v. 33, n. 4, p. 451-467, 2004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760042000221826 [ Links ]

MILLIGAN, Jeffrey A. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy. Schooling and Ethno-Religious Confict in the Southern Philippines. Singapure: Palgrave/MAcMillan, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1228-5 [ Links ]

PHILIPINNES. BOARD OF EDUCATION SURVEY (The); MONROE, Paul. A Survey of The Educational System of The Philippines Islands. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1925. [ Links ]

PHILIPPINE EXPOSITION BOARD (The). Circular Letter of Governor Taft and Information and Instructions for the Preparion of the Philippine Exhibit for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition to be Held at St Louis, Mo, USA, 1904. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing, 1902, p.32-33. [ Links ]

POLLEY, Mary E.; BATICA Andres. Rosa at Home and School. Primer Philippine Child Life Readers. New York: D. C. Heath and Co; Rochester, NY: The Lawyers Cooperative Publishing Co., [1928]. [ Links ]

PRATT, Mary Louise. Os olhos do Império. Relatos de viagem e transculturação. Bauru: EDUSC, 1999. [ Links ]

RYDELL, Robert W. All the World’s a Fair. Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1984. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226923253.001.0001 [ Links ]

RYDELL, Robert W. Interview with Robert Rydell. Race - The power of an illusion. Disponível em: https://www.pbs.org/race/000_About/002_04-background-02-11.htm#top 2003. Ultimo acesso: 02 ag. 2021. [ Links ]

RYDELL, Robert W. World of Fairs. The Century of Progress Expositions. Chicago: The University Chicago Press, 1993. [ Links ]

STEINBOCK-PRATT, Sarah Katherine. "A great army of instruction": American teachers and the negotiation of empire in the Philippines. 2013. Tese de Doutorado. 315f - The University of Texas at Austin. Austin, 2013. [ Links ]

TARR, Peter J. The Education of The Thomasites: American School Teacers in Philippine Colonial Society, 1901-1913. 2006. Dissertation (Doctor of Philosophy) - Graduate School of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2006. [ Links ]

UNITED STATES. PHILIPPINE COMISSION. Annual Report, War Department, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1915, Report of the Philippine Comission to the Secretary of War, July 1, 1913, to December 31, 1914 (in one part), Washington: Government Printing Office, 1915. [ Links ]

UNITED STATES. PHILIPPINE COMISSION. Fifth Annual Report of the Philippine Comission, 1904. Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department. Part 3. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905. [ Links ]

UNITED STATES. PHILIPPINE COMISSION. Fourth Annual Report of The Philippine Comission. Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department. Part 3. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904. [ Links ]

UNITED STATES. PHILIPPINE COMISSION. Report of the United States Philippine Comission to the Secretary of War for the Period From December 1, 1900, to October 15, 1901. The Division of Insular Affairs, War Department. Part 2. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901. [ Links ]

UNITED STATES. PHILIPPINE COMISSION. Seventh Annual Report of the Philippine Comission, 1906. Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department. Part 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907. [ Links ]

UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA. American Primers: Guide to The Microfiche Collection. Introductory Essay By Richard L. Venezky. Bethesda, Md: UPA, 1990. Disponível em: https://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/academic/upa_cis/3453_americanprimers.pdf. Último acesso em: 13 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

WARDE, Mirian J. A industrialização das editoras e dos livros didáticos nos Estados Unidos (do século XIX ao começo do século XX). Educação & Sociedade, v.32, p.121-135, 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302011000100008 [ Links ]

WARDE, Mirian J. No rastro do autor: a trajetória de Sarah Louise Arnold, autora de livros de destinação escolar. MORTATTI, M. R. L.; FRADE, M. I. (org.). História do ensino de leitura e escrita: métodos e material didático. 1ªed.São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2014, p. 61-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.36311/2014.978-85-393-0541-4.p61-92 [ Links ]

WARDE, Mirian J. Oscar Thompson na Exposição de St. Louis (1904): an exhibit showing “machinery for making machines”. FREITAS, Marcos C. Os Intelectuais na História da Infância. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002, p. 409-458. [ Links ]

WILSON, David N. Comparative and International Education: Fraternal or Siamese Twins? A Preliminary Genealogy of Our Twin Fields. Comparative Education Review, v. 38, n. 4, p. 449-486, Nov., 1994. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/447271 [ Links ]

WINSLOW, Erving. The Anti-Imperialist League. Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Boston: Anti-Impérialist Leagues, 1899. [ Links ]

1With the support of CNPq. English version by Staff Apoio Administrativo Terceirizado Ltda. E-mail: staff.apoioadmterceirizado@gmail.com. Revision done by Luiz Ramires Neto. E-mail: lularamires@alumni.usp.br.

2Jingoism” in English; jingoísmo in Portuguese. Word rarely used today, but widely found in documents of the period. Synonyms: xenophobia, nationalism, patriotism, parochialism, nativism, xenophobia and chauvinism.

3 In additional acts of the Congress - the Teller Amendment (1898) and the Platt Amendment (1901) - the United States extended its conditions of control and exploitation of Cuba; T. Roosevelt reaffirmed them in his second term. The United States maintained Cuba as a “protectorate” until 1933 when it supported Fulgencio Batista for president. After two long and dictatorial terms, Batista was removed from power by the Revolution of 1959.

4It refers to George Dewey, admiral who commanded and won the battle against the Spanish fleet in 1898, thus beginning the domination of the United States over the Philippines.

5Andrew Carnegie was one of the movement's biggest backers. Also worthy of attention are the anti-imperialist arguments of Mark Twain recorded in different media. Alexander (2018) lists a substantial part of Twain's writings on the subject.

6Farewell Address: George Washington's final address to his fellow citizens as he leaves the presidency. He wrote the speech in 1796 but never delivered it. In it, Washington discusses the dangers of divisive partisan politics and strongly warns against permanent alliances between the United States and other countries.

7 Krag: type of carbine brought by the United States to the Philippines during the invasion and domination. As defined by a gun sales website: “.30-40 caliber, 22" barrel, S/N 260196. Walnut stock. Filipinos were not comfortable with full-body rifles. After the turn of the century, several M1899 Krag carbines, along with some M1898 carbines, were altered for police use, equipping them with cut M 1898 Krag rifle stocks, equipped with swivel slings and bayonet handles. The ends of the larger diameter carbine barrels were turned down to allow the use of the standard bayonet. These modified Krag carbines looked like miniature rifles and are now commonly known as Philippine police rifles.” Available at: https://www.cowanauctions.com/lot/us-krag-model-1898-philippine-constabulary-rifle-160567. Accessed on: Aug, 19th 2021.

8 The book was released in 1934, posthumously, thanks to the initiative of former students of George H. Mead.

9The theses defended by Mead are post-World War I and contemporary with the rise of Fascism and Nazism. It is necessary to think of them, necessarily, in this context. As well as thinking of William James as the most direct heir of England's independence and as a witness to the Civil War; moreover, dead in 1910, James escaped witnessing the eruption of barbarism in subsequent years. On the set of manifestations of William James against the expansionism of the United States, especially the domination over the Philippines, see Coon (1996).

10In 1803, the United States gave France 15 million dollars for the territory of Louisiana, which was 2,144,476 km² (529,911,680 acres). The French territory of Louisiana - which was called New France - included, in whole or in part, the regions of present-day Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Montana, Wyoming and Colorado; that is, 23% of the current territory of the United States. Accessible at: http://www.blm.gov/natacq/pls02/pls1-1_02.pdf.

11According to Rydell (1993), the Missouri Historical Society did “oral history” with visitors to the St. Louis Exposition and recorded that the Philippine Reservation left them astonished at what they saw. He considers the joint displays by American Indians and Filipinos a demonstration of US government imperialism, but one that would not have been as brazen as the displays of the same nature in Seattle later in 1909 were.

12The Philippine Commission was the body appointed by the President of the United States to assist him in governing the Philippines. Two commissions with executive powers were appointed, in 1899 and 1900; two years later, the commission also gained legislative powers. In 1916 it was abolished in favor of a senate as the upper house of the Legislature (HALILI, 2004).

13“Thomas - Army Transport Ship, US Thomas, which transported 523 of the first 1,000 to Manila in July 1901” (TARR, 2006, p. 9). Tarr estimates that 2,000 Americans taught in the Philippines for a year or more during the first decade of the 20th century. Two months before the “thomasites”, 46 other pioneer teachers had arrived.

14The website WorldCat Identities states: Baldwin’s reader (first year), traducción p/ castellano-visaya p/ Captain Edward P. Lawton del 19º Regimento de Infanteria e P. Antonio Medalle for use in the schools of Visayan Islands, Philippines [1905]; however, no reference to this Baldwin's reader translation was found in the official documents or in the consulted bibliography. Available at: http://worldcat.org/identities/viaf 126146029612935822336/. Access in: Jul, 18 2021.

15All titles in this and the following tables are recorded here as they appear in the Official Reports.

16No book with this title has been found to date. As such, it was not possible to confirm neither that the grammarian Joseph Henry Allen Nenhum was the author or among the authors.

17E. B. Bryan had been superintendent of education in the Philippine Islands, and in 1904 he was teaching Education and Psychology at Indiana State University, Bloomington, Ind. His speech on Education in the Philippines stands as irrefutable testimony that the Igorots and Moros were not Pure-blooded Filipinos, that is, were not Christian Filipinos (BRYAN, 1904). In the same volume, there are other interventions on the Philippines.

18 Research needs to be carried out further so that one can confidently state what is suggested in the official reports: books with the name of Baldwin practically disappear from purchase lists to give the first place to Sarah Arnold and other authors and titles. Furthermore, it is necessary to confirm the circulation in Philippine schools of Baldwin's translations into Castellano-Visaya.

19Reference to books by Sarah Arnold translated into Spanish for use in the Philippines is found only in Iiams (1980, p. 52, note 2): Arnold's The Stepping Stones to Literature "has had Spanish editions, sometimes stated as intended for use in the Philippines”.

20Milligan cites Saleeby himself, Najeeb M. Sulu Reader for the Public Schools of the Moro Province as a source of this information. Zamboanga City: Mindanao Herald Press, 1905. Regarding the treatment given to the Moros, Tarr (2006, p.451, note 78) presents the following considerations: “Most of the Moro children who received schooling were enrolled in Islamic pandita schools. independent, managed by Moro clerics. The American schools in Zamboanga were unusual because enrolled Moro and Christian children; were also unusual in that Christian children were taught in Spanish and English, while Moro children were taught in the local Moro language, in Arabic characters, using Arnold Readers translated by Najeeb M. Saleeby, the first superintendent of education for the province of moro. See Wolcott, 'My Philippine Experiences'. American attitudes toward pandita schools, which they did not regulate, have varied over the years. Some educational superintendents and governors favored and encouraged them; others refused to recognize its legitimacy. In American schools, Moro children were barely represented, and their number, relative to total enrollment, grew rather slowly in the early years, in part because of Moro's intense suspicion that public schools were agents of Christian evangelization. In the 1904 school year, only 2,114 children were enrolled in public schools in the province of Moro, of which 240, or 11%, were Moro. In 1906, the total enrollment was 4,231, of whom 570 were Moro (13%) and about 80 were Pagans (2%). In 1909, enrollment was 5,042, including 843 Moros (16.7%) and 122 Pagans (2.4%). In 1913, the last year of military rule in Mindanao, the total enrollment was 7,568 (average daily attendance was less than 60%); at that time, 1,825 Moros were enrolled (24%) and 525 Pagans (7%) [...] Using conservative numbers - a Muslim population of 350,000, 20% school age - would give a school age population of 70,000 for those years. Thus, in 1909, Muslim enrollment would have been 1.2 percent of the school population, compared to about 25 percent in public schools for Christian children across the archipelago.”

21In the guide published by the University Publications of America, American Primers (1990), six textbooks adapted for the Philippines are listed. Four were not found in the official reports consulted: Mary E. Coleman, Margaret A. Purcell, O. S. Reimold e John W. Ritchie. The Philippine Chart Primer. Philippine Education Series. New York and Manila: World Book Co., 1908; Mary E. Polley e Andres Batica. Rosa at Home and School. Primer. Philippine Chilf Life Readers. New York: D. C. Heath and Co.; Rochester, N. Y.: The Lawyers Cooperative Publ. Co., 1928 e Sydney A. Campbell. The Illustrated Philippine Reader. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1905. From Baldwin, the Reader First Year, translated into castellano-visaya, also does not appear in the reports; only the original version in English appears (Table 1). Finally, two are in the official reports: by Sarah Arnold, Arnold Primer and Stepping Stones...first reader, this one with Charles Gilbert as co-author (Tables 2 and 3).

22It is worth remembering here the order that Oscar Thompson made in 1904 to the publisher to adapt and translate the booklet, targeting the public schools of Saint Pauls (WARDE, 2002).

23On Wikipedia this animal is presented as follows: “The carabao (Spanish: Carabao; Tagalog: kalabaw) is a domestic marsh buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) native to the Philippines. Carabaos were introduced to Guam from the Spanish Philippines in the 17th century. They have acquired great cultural significance for the native Chamorro and are considered the unofficial national animal of Guam. In Malaysia, carabaos (known as kerbau in Malay) are the official state animals of Negeri Sembilan.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carabao).

24Tarr's doctoral thesis (2006) is one of the most comprehensive and critical studies on “thomasites; It also contains, in addition to more precise data and concepts about the aforementioned teachers and their performance in the Philippines, a vast bibliographic review that includes memories of teachers who composed that group, of which, here, two of the easiest access in the literature stand out on online archives: Mary H. Fee, A Woman's Impressions of the Philippines, 1912 and William B. Frer, The Philippine Experiences of An American Teacher, 1906. Tarr verticalizes his analysis in the performance of seven “thomasites”.

25Although giving the thomasites the right dimension, there is no way to minimize the fact that the Peace corps affirm its origin in this group of teachers which they refer to as “an army like no other” (KRAMER, 2006; 1998; WILSON, 1994; Karnow, 1990).

26What is known about Adeline Knapp owes much to what Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935) wrote about her in her autobiography, letters, and diary, and to what Gilman's biographers have said about her. Also known by her second husband's surname, Charlotte Perkins Stetson, she became very famous in the United States and abroad both for her poetry, short stories, novels and for her public positions in favor of immigrants, the poor, female autonomy and, above all, the female vote, recorded in lectures, newspaper articles, etc. There is plenty of evidence that Adeline and Charlotte would have been girlfriends, as well as partners in newspapers and other ventures. The rupture was dramatic, and they ended up following opposing political and ideological paths. Unlike Knapp, Perkins has won many works about her until today (DAVIS, 2010; HILL, 1980).

27She opens by saying that this was the most important of the three voyages that had elapsed since the Spanish-American War; the happiest; the one that should bear the best fruit! The first would have been the voyage undertaken by the Spaniards back to their land. The second is the one that brought Hispanic-American professors from Cuba to the United States “to study American methods and ideas in a large summer school at Harvard University [...] It was a generous and gracious act on the part of that government [of the United States], and this expedition was as happy as the other [first] was sad (KNAPP, 1901, p. 11). She continues to distribute grandiose words of hope in that army without weapons capable of accomplishing what is characteristic of the “American genius”: to go deep into the jungle, in the inhospitable, to meet “a people that neither knows nor understands the basic principles of our civilization, but which, for our mutual happiness and liberty, must be brought into agreement with us.” Knapp ends up calling these people “compatriots”. This was the American “genius”: to face the “other man” as a similar to pull him out of incivility towards the designs imposed on them (KNAPP, 1901, p. 11-12)