Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-119

Dossier 4 - Transnational circulation of reading books and pedagogical manuals (between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century)

‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’: Schoolbooks to Instill Fascism Among Italians Abroad, the Brazilian case (1922-1938)1

1University of Caixas do Sul (Brazil). taluches@ucs.br

Schools with ethnic marks left by language, knowledge and way of operating spread across Brazil in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Since 1870, Italian schools would be inspected by consuls linked to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Books were shipped and distributed through consuls who were key figures in fascism. The objective is to understand the policies, production, circulation and distribution of schoolbooks made during fascism for Italian schools abroad, with special attention to those that circulated in Brazil between 1922 and 1938, when ethnic schools were nationalized and closed. An example is ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, a book of “brief news about a small people who knew how to give the world a great civilization” (FASCI ITALIANI, 1932, p. II). From the History of Education and Cultural History, a historical documentary analysis of laws, mailing, reports from consuls, photographs, schoolbooks and newspapers was carried out.

Keywords: Schoolbooks; Fascism; Italian schools in Brazil

Escolas com marcas étnicas pelo idioma, saberes e modo como operavam se proliferaram no Brasil em fins do século XIX e início do XX. Escolas italianas foram inspecionadas por cônsules ligados ao Ministério das Relações Exteriores desde 1870. A remessa e distribuição de livros foi efetivada por meio de cônsules que, no fascismo, foram centrais. O objetivo é compreender políticas, produção, circulação e distribuição de livros escolares fabricados durante o fascismo para as escolas italianas no exterior, atentando para aqueles que circularam no Brasil entre 1922 até 1938 quando da nacionalização e fechamento das escolas étnicas. Como exemplo, ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, livro de “breves notícias sobre um pequeno povo que soube dar ao mundo uma grande civilização” (FASCI ITALIANI, 1932, p. II). A partir da História da Educação e História Cultural foi realizada a análise documental histórica de leis, correspondências, relatórios de cônsules, fotografias, livros escolares e jornais.

Palavras-chave: Livros escolares; Fascismo; Escolas italianas no Brasil

Escuelas con marcas étnicas por el idioma, saberes y modo de operar proliferaron en Brasil a fines del siglo XIX y principios del XX. Escuelas italianas fueron inspeccionadas por cónsules vinculados al Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores desde 1870. La remesa y distribución de libros fue efectuada por medio de cónsules que fueron centrales durante el fascismo. El objetivo es comprender las políticas, producción, circulación y distribución de libros escolares fabricados durante el fascismo para las escuelas italianas en el exterior, con énfasis en los que circularon en Brasil entre 1922 y 1938, en época de nacionalización y cierre de las escuelas étnicas. Como ejemplo, ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, libro de “breves noticias sobre un pequeño pueblo que supo dar al mundo una gran civilización” (FACI ITALIANI, 1932, p. II). A partir de la Historia de la Educación y de la Historia Cultural fue realizado un análisis documental histórico de leyes, correspondencias, informes de cónsules, fotografías, libros escolares y periódicos.

Palabras clave: Libros escolares; Fascismo; Escuelas italianas en Brasil

Initial Considerations

The migrations of those who left Italy and settled in different places in Brazil between the end of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century produced conditions for the establishment of schools with ethnic marks resulting from language, knowledge and way of operating. Schools which proliferated in the Brazilian context, in urban and rural areas, but with unique nuances and characteristics. Operating in different manners, the so-called Italian schools on Brazilian soil were inspected by consuls and consular agents linked to Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, since 1870. In Rio Grande do Sul, several of these schools had ties with mutual aid associations, or with private teachers, or even with a local parish priest, as an Italian parish school. Or simply as an initiative of a group of families to offer their children conditions to read, write and count (and pray), that is, as an ethnic-community school. Most school initiatives of an Italian ethnic nature were ephemeral (Luchese, 2015), but it is true that some schools remained open for decades, despite instabilities and significant changes, as found by Rech (2016) in relation to the capital of Rio Grande do Sul.

The role of Italian diplomacy as a link between those who migrated and Italy was an important one, played under patriotic colors, it is true, but which gained very specific contours as of the mid-1920s, when Mussolini established a whole set of policies targeted at emigrants and descendants, which also resonated in cultural and educational matters. The emigrants became ‘Italians abroad’, and monitoring and tutelage policies underwent changes. Book shipping and distribution, school grants being sent, inspection, and even the referral of teachers were experiences that had been carried out since the end of the 19th century, albeit with some inconstancy, by Italian authorities in relation to the school. But the policies constituted by fascism were distinct and reverberated in the Brazilian and Rio Grande do Sul contexts.

Considering Italy’s fascist policies between the 1920s and 1930s and the country’s relations with Brazil, the objective is to understand the policies, production, circulation and distribution of schoolbooks made during fascism for Italian schools abroad, with special attention to those that circulated in Brazil between 1922 and 1938, when ethnic schools were nationalized and closed. The focus of the analysis is the book ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, a work of “brief news about a small people who knew how to give the world a great civilization” (FASCI ITALIANI, 1932, p. II). By scrutinizing the production of said book, thinking of it as a cultural asset, I seek to perceive in the materiality, in the support, the discursive crossings that constitute it through the texts, images and maps that are analyzed. Small evidence of its distribution and circulation was identified and is presented.

Based on the History of Education and Cultural History, and mobilizing the concepts of representation and production (Chartier, 2002, 2009, 2010, 2014 and 2017), in particular, a historical documentary analysis was carried out by means of laws, mailing, reports from consuls, photographs, schoolbooks and newspapers, which, crisscrossed, allow noticing some historical nuances. As mentioned by Choppin (2000), schoolbooks are complex objects that take on several functions. As supports of truths, they present notions of different orders. Manuals transmit values, result from specific cultural contexts, in this case, fascism in Italy, and the Vargas Era (1930s) in Brazil. Furthermore, they can be thought of as pedagogical tools, intended to facilitate learning, to spread ways of thinking and making sense of the world.

When narrating this story, the set of representations evoked on the pages of the book were thought of in the light of educational and cultural policies produced in Fascist Italy and which echoed in Brazil and in Rio Grande do Sul. In a first analytical movement, I narrate the traces of fascist policies and how they operated in the context of the southern state, with special attention to schools and cultural initiatives. In a second moment, I adjust the focus to think about the production of one of the books, ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, and analyzing this work, I intertwine the representations evoked, their relationship with the policies and discourses it disseminated, seeking to conform and educate for fascistization.

Italian fascist cultural and educational policies and their resonances in Rio Grande do Sul in the 1920s and 1930s

The school, as a space for spreading Italianity and assisting emigrants, had been thought of by the Italian government for many years. As mentioned, since 1870, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was responsible for monitoring, inspecting and disseminating Italian schools abroad. Consuls, diplomatic agents and even some Italian laws, such as those enacted in the Crispi government (1889), sought to financially support and draw emigrants and their children closer to Italy, especially by sending textbooks and some grants, since the end of the 19th century (Floriani, 1974). However, as I have mentioned in another manuscript, “the Italian foreign policy fluctuated, and the great mass of emigrants, spread across different countries around the world, was faced with different practices for the promotion and maintenance of Italianity ties, for the dissemination of the Italian language, of which so many emigrants were not aware, since they used regional dialects” (LUCHESE, 2017, p. 129). It should be mentioned that, at the dawn of the 1920s, there were few Italian schools in the context of Rio Grande do Sul, since the growing supply of free public or Catholic confessional schools offered options to immigrants and their descendants (LUCHESE, 2015). The attempt of resumption and the efforts made to do so with the establishment of a network of schools, as stated by Rech (2016), grew at the end of the 1920s.

In addition to the consuls’ role, the Società Dante Alighieri as a lay society2, the Italica Gens Federation (Catholic)3 and the Mutual Aid Associations are important, and so is the formation of the fascio all’estero4 and Doppolavoro5, which were present in Rio Grande do Sul. Despite all the mobilization of fascist policies aimed at ‘Italians abroad’, there is a gap of a few years, and this results in significant differences.

The establishment of the ‘Opera Nazionale Maternità ed Infanzia’ (1925), for assistance to popular and disadvantaged classes, the ‘Opera Nazionale de Dopolavoro’ (1926), for the promotion of physical and health activities for workers, the Opera Nazionale Balilla (1926), later replaced by Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (1937), responsible for activities targeting children and youth, are actions of the Italian context that also have repercussions on Rio Grande do Sul’s soil.

Young people and children emerged as the main target of the educational policy and propaganda of Fascism, because through them they could enter the private and public life of the Italian population. Schools, universities, workers’ associations (Dopolavoro), cinema and youth organizations took on the role of educating the ‘new man’ and spreading the political culture of the new regime. In Fascism institutions, boys and girls received an education focused on the fascist life, where they learned which values to internalize, how to behave in daily life, whom to idolize, and what social roles to take on. Boys were educated to be good fathers, good workers and good soldiers, whereas girls learned that a woman’s role was to take care of their homes, husband, offspring, in addition to reproducing the greatest number of children to make up the armies of workers and soldiers of Fascism. (ROSA, 2009, p. 622)

Fascism marks discourses with gender divisions, representing the man as the responsible soldier, with his virility and Roman virtue, to multiply the lineage, fight the enemy, while women, seen as naturally mothers, sheltered in their houses, reproduced the sacred values of family, embracing her maternal vocation, accepted as a teacher in childhood schools. It is relevant to situate fascism in a framework that factors in the set of ideological proposals, the mobilization of social-control tools, as well as international political strategies for cultural diffusion and propaganda.

Another fascist initiative for Italians abroad was the creation of an Inter-Ministerial Committee for the expansion of Italian culture in receiving countries. Also, Salvetti (2009) highlights that the main fascist action in relation to subsidized Italian schools was the sending of new textbooks permeated with the fascist ideology. Fascism, from its early years, sought support and a means for dissemination and conquest of followers in associations, newspapers and schools supported by Italians or descendants abroad. For Bertonha (2001), “the fascist government began to conquer the Italian school system abroad as early as 1923/1924, when several laws centralized the schools and accentuated their role of educating Italian young people abroad in an Italian manner” (p. 48).

The establishment of the General Directorate of Italian Schools Abroad (DGSIE), directed in Ciro Trabalza, and a commission dedicated to reorganizing and inspecting Italian schools in America, promoted a reorganization of the schools now called ‘Italian schools abroad’ (BARAUSSE, 2016). The most systematic offensive occurred with the appointment of Piero Parini to the General Directorate of Italian Schools and People Abroad, and as Plenipotentiary Minister; he placed emphasis on propaganda and on an education with totalitarian, fascistizing nuances. Parini also took on the role of secretary of the Fasci italiani all’estero, and his visit6 to RS, in 1931, was remarkable for the renewal of a set of cultural practices that expanded and gained strength in disseminating the feeling of belonging and in fostering the fascist propaganda in RS, with said practices being also materialized through books coming from Italy to the newly created libraries and reading rooms. Contributing to the expansion of these policies, there were consuls aligned with fascism and installed in the Italy Consulate General in Rio Grande do Sul, namely: Manfredo Chiostri, Mario Carli, Guglielmo Barbarisi and Santovincenzo Magno. In addition, it is important to remember the many free Italian courses being offered, for instance, at Dante Alighieri’s headquarters, in Porto Alegre. Not to mention the intense social agenda with plays, musical performances and civic rituals. As Beneduzi wrote (2011, p. 95), “in the regime’s propaganda project, many were the intellectuals, artists, representatives who, in some way, embodied this imagery construction of Italy as the maximum exponent of Western culture”.

In Table 1, I present, in a summary, some important policies for the dissemination and organization of the ‘Italian schools abroad’.

Table 1 Summary of the legislation and important events of the fascist educational policy for (elementary) ‘Italian schools abroad’ and ‘Italians abroad’

| Legislation | Prescription |

|---|---|

| Royal Decree No. 932, of April 19, 1923 | It established that teachers in Italian schools abroad should pronounce a solemn professional vow by which they promised to educate their students to love their country and have greater devotion to the king and his institutions. |

| Royal Decree No. 933, of April 19, 1923 | Creation of the Consiglio Centrale delle Scuole all’ Estero. |

| 16/04/1924 | Religious education is instituted in ‘Italian elementary schools abroad’. |

| Ordinanza 01/10/1924 | It established programs and set guidelines for Italian schools abroad. Through the diffusion of the Italian language and culture, of the national feeling, in the most diverse colonies scattered around the world, of the great fascist achievements, it sought to strengthen relations, influences and, in this way, also the gains for the homeland Italy regarding Italians from abroad and recipient countries. |

| Decree No. 177 of 21/01/1926 | It sets standards for the choice of teachers and management of ‘Italian elementary schools abroad’. |

| Decree of 10/12/1926 | Creation of Institutes of Italian Culture Abroad. |

| Decree No. 628 of 28/04/1927 | It abolished the General Emigration Commission and instituted the General Directorate of Italians Abroad. Within this Directorate, the Office of Propaganda for the Overseas was created. |

| Decree No. 1575 of 12/08/1927 | Approval of changes in school schedules and programs. |

| Decree No. 18 of 12/12/1929 | It established the General Directorate of Italians Abroad and Schools, under the administration of Piero Parini, general secretary of the Italian Fasci abroad. |

| 1929 | Institution of the single text for schools in the kingdom and abroad. |

| In 1932 | Mandatory affiliation of teachers to the National Fascist Party. |

| Service Order No. 24 of 25/09/1932 | It unified the General Directorate of Italians Abroad and Schools with the General Directorate of Italian Work Abroad. |

Source: Organized by the author from Floriani (1974).

The expansion of the fascistization action of schools on the part of the state apparatus through the provision of subsidies, books and teaching materials, as well as by sending teachers and educational directors, gained greater evidence throughout the 1930s. The book, as “un producto fabricado, difundido y consumido” (CHOPIN, 2000, p. 110), gained clearly fascist contours. As analyzed by Giron (1998, p. 100), “Teaching texts before the fascist reforms were uninteresting: long and tedious. Few images are displayed to illustrate the endless descriptive texts.” On the other hand, the same author, when analyzing the books sent by the Italian government during the fascist period, states:

From a formal point of view, fascist books are of better graphic quality. They feature more pictures than text, many of the illustrations are in color. They have maps, printed with the necessary colors for one to understand the legends. Fascist textbooks are interesting. Each short text comes with examples and pictures that suit the topic addressed (GIRON, 1998, p. 100).

Fascistization policies resonated in several countries in America, but also in Europe itself, Africa and Asia, as pointed out by Pretelli (2009, 2010), Salvetti (1995, 2009). Zago (2020), for instance, speaks about the transnational fascistization strategies of the Italian regime in the Mexican context, analyzing with greater attention the actions of a Salesian girls’ school in the period.

However, in the Brazilian context, the period coincides with the Getúlio Vargas government and the nationalization agenda, accentuated with the New State in 1937. And in the case of Rio Grande do Sul, with the presence of Flores da Cunha as governor, who expands state educational policies with a comprehensive reform of Rio Grande do Sul’s schools. It is worth remembering that, in 1935, he created the State Secretariat for Education and Public-Health Matters (Sesp), regulated the teaching career and adopted new criteria for the appointment and removal of teachers. He broadened the network of schools and their physical structures, as well as student coverage and teacher appointment. According to Bastos and Tambara (2014, p. 86-87), “[...] in 1930, there were 718 teachers, with 2,131 municipal schools and 1,320 private schools; in 1937, the number of school units rose to 5,346, with 902 state schools, 2,807 municipal schools, and 1,637 private schools”. A substantial increase which, added to the work of the Technical Section of the General Directorate of Public Instruction and of the Center for Research and Educational Guidance (CPOE/RS), modernized and sought to nationalize education in Rio Grande do Sul.7

Educational and cultural policies produced in the context of fascist Italy are faced, in the Brazilian context, with events and attempts to expand Brazilianness, to confront discourses that initially accommodate themselves, share space, but which gradually repel each other and start to prohibit and curb existence. This is the case of Italian ethnic schools, all closed in 1938 in Rio Grande do Sul. Thus, even after mapping the diversified set of cultural practices, the establishment of libraries, and analyzing some of the reading books, I recognize that a small portion of the members of the Italian bourgeoisie and the local middle classes had a closer contact with fascist propaganda.

‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’: The work and its production

The production and distribution of textbooks and reading books in the context of Fascist Italy takes on clearer contours, as mentioned above, from the end of the 1920s, exalting the regime’s efforts and achievements, disseminating representations of values and models about the homeland, respect for authorities, the central role of labor, the feeling of family, and the virtues of the ‘new man’, as Ascenzi and Sani (2009) state regarding the ‘Italian abroad’. The book, as a cultural asset, was crossed by such discourses. And the investments made by the regime for production were high. We know that “su produción material y consecuentemente su aspecto evolucionan con el progresso tecnológico y con el concurso de otros suportes de la información” (CHOPIN, 2000, p. 110), but in the case of Fascist Italy, there was a project to select and produce such works. From a considerable number of titles sent to Brazil, I selected a particularly significant one for analysis.

The book ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’ was a work aimed at Italian youths abroad. It is a 32-page publication with maps added at the end. It is 17 cm wide and 24 cm high. There is no authorship information, only the mention that it was owned by the Fasci Italiani all’ Estero, then directed by the aforementioned Piero Parini. And the publisher record: Istituto Geografico Giovanni De Agostini8. According to Morandini (2001, p. 260), Giovani De Agostini was born in Pollone, Piedmont region, on August 23, 1863, and complete his university studies in Turin and Berlin, publishing some cartographic studies and other writings at a very young age. The publisher with which he was connected benefited from fascism due to the strategic capacity of the leaders to converge with the regime’s objectives by valuing the national territory and the care with production, always attentive to technological advances in order to qualify images and maps, for instance. The appointment of Arnaldo Mussolini as honorary president, in the 1920s, was intended to bring the publisher closer to the regime. They began to publish works aimed at Italian libraries abroad, and the fascist regime financed publications sent to France and America. Even with World War II, works were produced and sent to Germany and Japan. The Istituto De Agostini remained in operation for nearly a century, publishing atlases, wallcharts for use in schools, the so-called fun geographical encyclopedia of the late 1930s, and several textbooks for use in schools and reading. In addition to publishing works with themes in the field of Arts and Tourism. If “texts do not exist outside the material supports (whatever they are) that vehicles are” (CHARTIER, 2002, p. 61 and 62), the mediation of the editor is central to the form and making of the work, and the choice of the Istituto De Agostini becomes clear as we advance in the analysis.

The quality of the work, considering the time it was printed, the use of colors, the selection and paper, the photographs and maps, allow understanding the relationship with the Istituto and the proposal of the regime as aspects that conformed to each other. The book features writings in Latin in some parts, recalling the heritage of the ancient Romans. Regarding the structure of the work, I present the following table:

Table 2 General structure of the book ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’

| Cover | It shows the title “Quando il Mondo era Roma”, an image representing the fascio symbol signed by A. Della Torre and, below, “Alla Gioventù Italiana all’estero”. |

| Spine | No pictures or writings. |

| Cover sheet | It brings the title “Quando il Mondo era Roma” followed by “Brevi Notizie su um piccolo popolo che seppe dare al mondo a grande civiltà”9, Rome as location, and MCMXXXII - X as date, i.e., 1932, 10 years of fascism. The marking of the count of the ‘fascist era’ has a celebratory nature and started to be done by legal order of 1926. |

| Back of cover sheet | “Dedicato agli italiani che vivono all’Estero e che di fronte agli stranieri devono sostenere l’onore e l’onore di essere gli eredi dell’antica Roma”10. Right below is this information: “La riproduzione del texto e delle illustrazione rimane di exclusiva proprietà dei Fasci all’ Estero”11. At the bottom of the page, “Istituto Geografico De Agostini S. A. - Novara, Sezione Calcocromia, Printed in Italy”. |

| Back cover | With the symbol of the Fasci italiani all’estero. |

Source: Organized by the author.

From the set of evidence presented in Table 2, we can already locate the work’s clear addressing, its objective and some representations: the honor of being a descendant of the ancient Romans, an honor to be carried by those who ‘live abroad’. It is known that the production of effects of senses, uses and meanings imposed by the forms of its publishing and circulation are important, but it is certain that, on the other hand, as Chartier writes (2010, p. 43), it is necessary to “understand how the concrete appropriations and inventions of the readers” signify the work in the context of its written culture. That is, on the one hand, restrictions and conventions and, on the other, the “way in which social actors give meaning to their practices and statements [...] the inventive capacities of individuals or communities” (CHARTIER, 2010, p. 49). As Galfré argued (2005, p. 27), “it is the government’s purpose - according to the official statement - to give the book not only the fascist vestments, but also the fascist soul”.

The cover is relatively simple, but brings a clear message. The drawing, shown in the left corner, is the symbol of the fascio and contains the illustrator’s signature: Angelo Della Torre. Inside the work, there are other drawings, such as reproductions of buildings or, for instance, of the hills on the banks of the Tiber, where Rome was founded. There are no new signatures, so we are left to wonder whether Della Torre was also responsible. According to a study by Colin (2012), Angelo Della Torre was a painter, sculptor and illustrator. Born in 1903 and died in 2000, he graduated in painting from the Fine Arts of Rome. According to Colin (2012, p. 475), Della Torre was

still active in the eighties, he was particularly happy representing children, of whom he effortlessly expressed the most diverse sensations and the most diverse feelings with his sober, discreet, always clear, sometimes harsh drawings, well supported by the gentle use of soft colors [...].

The style described by Colin is different from what is possible to analyze about the cover’s aesthetics and the colors used to represent the fascio. The symbology of the fascio12 was adopted, as explained by Tarquini (2011), to express the compact union of a group, and at first, the fascist program (1919) did not mention the values of the Roman world, but in 1921, Romanity becomes the main symbolic instrument of fascism. On the back cover, centered, is the symbol and identification of the copyright owner: Fasci italiani all’estero.

Source: Reproduced by the author from FASCI ALL’ ESTERO, 1932.

Figure 1 Front and back cover of the work ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, from 1932

The effects produced by typographic techniques (Chartier, 2009) that seek to regulate the reading action are well structured in the analyzed work, mediating text and images. All images are captioned, some are photographs, others are drawings/illustrations of themes to which one wants to draw attention. There is a cadence in the composition of the pages, since, following the written text, which is relatively short and presented in a large font, with good spacing, the reader is invited to read the written text and the images that accompany it. Everything arranged and correlated, seeking to build the meaning that one wants to produce, the reading protocols.

The work begins by recalling the distant times of the foundation of Rome, announcing the peoples who, living on the banks of the Tiber, such as Latins and Sabines, warrior peoples who set the narrative, composed Rome. “Città dal petto forte” [strong-chested city], the Etruscans would have intuited, as presented in the book. The Sabines would have said that Rome was the “città del fiume” [the river city] and, thus, the description begins to include a series of representations of who the Romans were and how they conquered, one by one, peoples and distant lands. The narrative comes with images - both photographs and drawings. For a more thorough analysis of the content of the work and its game of representations, from an attentive look to the text, I present two analytical categories, as shown in the table below:

Table 3 Content analysis of the work ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’

| Analysis categories | Excerpts from the work | Free translation by the author |

|---|---|---|

| Representations of the Roman | “Un po’pastori e um po’ agricoltori” (p.4). | “A little shepherds and a little farmers” (p. 4). |

| “Avvevano l’ ardimento dei marinai grechi, la robustezza e a tenacia dei montanari della Sabina, la intelligenza viva degli Etruschi. Modesti e frugali nell’appagare i propi bisogni, ostianti nel raggiugere uno scopo prefisso, abili nel trattare un negozio, sereni nel giudicare, pronti a qualsiasi fatica, coraggiosi nell’ affrontare il pericolo anche se ignoto” (p. 4 and 5). | “They had the boldness of the Greek sailors, the robustness and tenacity of the mountaineers of Sabina, the lively intelligence of the Etruscans. Modest and frugal in meeting their own needs, ostentatious in achieving a goal, skillful in dealing with business, calm in judgment, ready for any penury, courageous in facing danger even if it was unknown” (p. 4 and 5). | |

| “il senso de vincolo comune” (p. 5). | “the sense of common bond” (p. 5) | |

| “segnato sulla fronte dei rozzi romani l’impronta dei dominatori” (p. 5). | “marked on the forehead of the rude Romans with the mark of the rulers/dominators” (p. 5). | |

| “il romano [...] non vacila” (p.6). | “the Roman [...] does not waver” (p. 6). | |

| “Signori delle terre e dei mari” (p. 18). | “Lords of lands and seas” (p. 18). | |

| “sua fiducia e nel suo coraggio há trovato la capacità di regere il timone del mondo” (p. 21). | “their confidence and courage found the ability to rule the helm of the world” (p. 21). | |

| “prova materiale e tangibile di quello che è stato lo spirito civile che i Romani seppero diffondere, ognuno resta muto, smaritto” (p. 31). | “material and tangible proof of what the civil spirit that the Romans managed to spread was, everyone becomes mute, lost” (p. 31). | |

| “Se è vero che ‘la Storia insegni’, le vicende dell’antica Roma devono insegnare a tutti gli Italiani, anche a quelli que sono fuori dei confini, ad aver fiducia nei destini della Patria comi i Romani” (p. 31 and 32). | “If it is true that ‘history teaches’, the events of ancient Rome must teach all Italians, even those who live outside the borders, to have faith in the destiny of their homeland like the Romans” (p. 31 and 32). | |

| Representation of Rome, the Motherland | “Roma vince e dopo ogni vittoria, con l’espansione della conquista tocca confini di altri popoli, intacca nuovi interessi, si crea nuovi nemici” (p.5). | “Rome wins, and with each victory, with the expansion of the conquest, it reaches the borders of other peoples, reaches new interests, creates new enemies” (p. 5). |

| “Roma combatte” (p. 5). | “Rome fights” (p. 5). | |

| “la bela storia di conquista non si interrompe” (p. 5). | “the beautiful story of the conquest does not stop” (p. 5). | |

| “giusta legge, con la saggia amministrazione, com la tolleranza delle costumanze e delle religioni, irradiare quella luce di civiltà che illuminò i primi passi di molti popoli e di molti paesi” (p. 15 and 16). | “fair law, with wise administration, with tolerance of customs and religions, to radiate that light of civilization that illuminated the first steps of many peoples and countries” (p. 15 and 16). | |

| “gloria della Città dominatrice, del Capo del Mondo” (p. 18). | “glory of the ruling city, of the head of the world” (p. 18). | |

| “Il Romano ha sempre avuto un’enorme fiducia in sè stesso e nei destini della propria pátria” (p. 21). | “The Roman has always had enormous confidence in himself and in the destinies of his homeland” (p. 21). | |

| “testemoniare lo splendore di Roma perfino in quelle località ove oggi è tornata la solitudine” (p.31). | “witness the splendor of Rome also in the places where loneliness has today returned” (p. 31). |

Source: Organized by the author from the work.

In the game of representations, the appeal to the relations between the exaltation of ancient Rome and the new Italy and the ‘new man’ that the fascist regime sought to establish are evident. Senses of grandeur, dominance and superiority over other peoples, the recurrent idea of fight, of conquest... there are several senses that one wanted to intuit between the ‘splendid’ past and the future being built by fascist action. As Chartier teaches, “the page layout, the way of dividing the text, the conventions that govern its typographic presentation” (CHARTIER, 2017, p. 35) are means by which authors and/or editors exercise ways in which they can “express an intention, to govern reception, to repress interpretation” (CHARTIER, 2017, p. 35). And in the case of ‘Il Mondo era Roma’, to direct a set of representations that are not enough with the written narrative, but comes with images - illustrations and photographs - distributed throughout the work. Thus, recognizing how richly the book was illustrated, I present the cataloging in the table below, to provide better argumentative precision on the dimension and the tone of its presence in the work:

Table 4 Mapping of the images present in the work

| Page | Image |

|---|---|

| 1 | Drawing of the ‘Hill on which the city of Romulo stands”. |

| 2 | Busts of Scipione the African and Mario. |

| 3 | Busts of Silla (described as Rome’s first dictator) and Pompey the Great. |

| 4 | Bust of Giulio Cesare and image of the Roman trireme. |

| 5 | Bust of Cesare Ottaviano Augusto. |

| 6 | Photograph of Tunisia, former port of Carthage. |

| 7 | Fascio - “sono il símbolo della unità, della maestà, della forza dello Stato. Ricordiamo l’origine agricola di Roma e la fusione di vari popoli, nella nuova città”13. |

| 8 | Photographs of Spain, Seville - Roman wall and Spain - Sagunto - Roman theater. |

| 9 | Missing in the copy. |

| 10 | Missing in the copy. |

| 11 | Photographs of France - Orange - Arch of Triumph; France - St. Rhemy - Mausoleum of the Giulli and France - Nimes - Temple of Diana. |

| 12 | Photographs of France - Nimes - Roman aqueduct; drawing of the wall and guard post of the Danube borders. |

| 13 | Drawing of Hadrian’s wall in Great Britain; Photograph of Germany - Colonia - Roman tower and drawing of Yugoslavia - Spalato - reconstruction of Diocletian’s Mausoleum. |

| 14 | Photographs of Yugoslavia - Spalato - Diocletian’s Palace, the Golden Gate and Yugoslavia - Spalato - Diocletian’s palace peristyle. |

| 15 | Model photography - Romania - Adamaclisi - Trajan’s trophy and photography Greece - Athens - Hadrian’s library. |

| 16 | Drawing of the wall in Dacia and photography Greece - Athens - Hadrian’s arch. |

| 17 | Photographs of Greece - Thessalonica - Pillar of the Arch of Valerius and Africa - Cyrene - Temple of Apollo. |

| 18 | Africa - Tunisia - Susa - mosaic of Virgil and photograph of Africa - Cyrene - basilica of Apollonia. |

| 19 | Photographs of Africa - Tunisia - the amphitheater (internal) and Africa - Tunisia - the amphitheater of El Gem, external view. |

| 20 | Photographs of Africa - Tripoli - Sábrata - the capital and the theatre. |

| 21 | Photographs of Africa - Tripoli - the basilica from two angles. |

| 22 | Photographs of Africa - Tripoli - aqueduct’s cistern and Marco Aurélio’s arch. |

| 23 | Photographs of Africa - Tripoli - the spas and Algeria - the triumphal arch |

| 24 | Photographs of Africa - Algeria - the forum and theater columns |

| 25 | Photographs of Africa - Algeria - forum columns and the theatre. |

| 26 | Photographs of Asia - Ephesus - theater scene and Africa - Algeria - Trajan’s Arch. |

| 27 | Photographs of Turkey - Constantinople - Justinian’s Aqueduct in Pyrgos and Obelisk of Theodosius. |

| 28 | Photographs of Asia - Turkey - Ankara - Temple of Augustus and Rome; Syria - Temple of Trajan. |

| 29 | Photograph of Asia - Syria (currently Jordan) - Gerasa - panorama of the ruins and forum columns. |

| 30 | Photograph of Asia - Pamphylia (Turkey) - Hadrian’s Arch and Aspendo - Roman theater. |

| 31 | Photographs of Asia - Arabia - Petra - the wall and Syria - the great temple of Heliopolis. |

| 32 | Photographs of Asia - Syria - Damascus - the citadel and drawing of the castle on the bridge of Deutz, Germany. |

Source: Organized by the author from the analysis of the work.

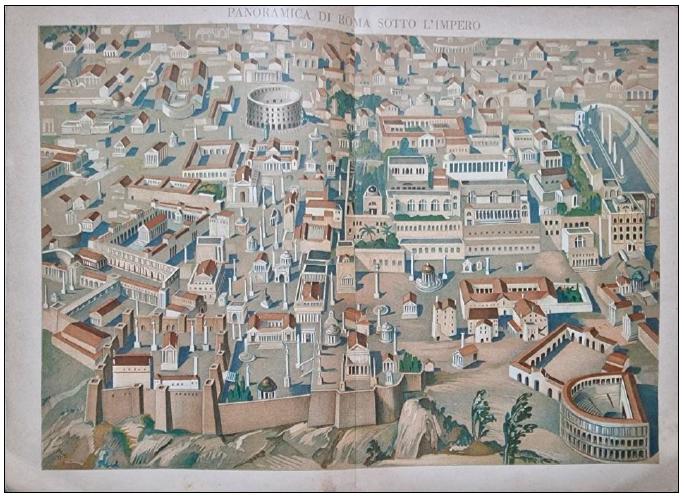

On several pages, two images and their captions take up all the space. In the middle of the work, a colored drawing - as an insert - presents the reader with a panorama of Imperial Rome, as shown in Figure 2:

Source: Reproduced by the author from FASCI ALL’ ESTERO, 1932, colored-illustration insert in the middle of the work.

Figure 2 Colored insert ‘Panorama of Rome in the Empire’

The richness of details, the colors, the way of presenting Rome as a model of ancient imperialism, the remembrance of a memorable past that had to be recovered. In the visuality presented by the succession of images, “the process by which readers, spectators or listeners make sense of the texts (or images) they appropriate (CHARTIER, 2010, p. 35 and 36) was also being conducted by the text.

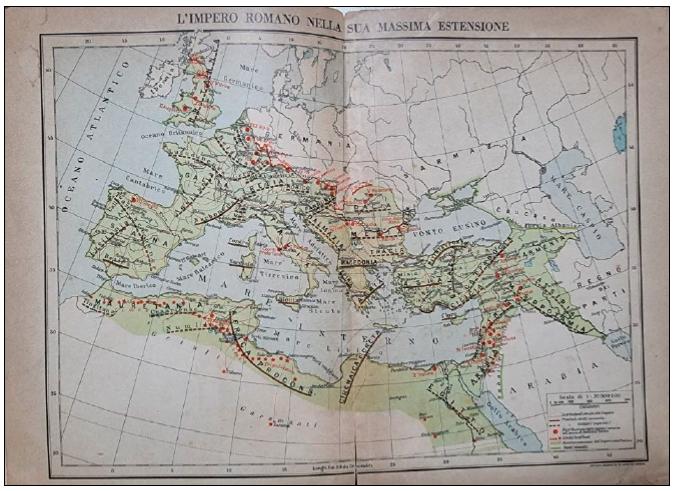

It should be noted that, in addition to the images, the Istituto Geografico De Agostini produced the maps that are included in the work. The colored maps that come with the publication are arranged at the end of the numbered pages and include: (1) the eagle’s nest with the representation of Rome’s dimensions, foundation, and the expansions that took place in the Monarchy, Republic and Empire; (2) Rome and the border peoples in the 5th century a. C.; (3) Rome and its allies in the Samnite confederation in 298 BC. C.; (4) Expansion of the Roman territory in Italy during the social war; (5) Progressive expansions of the Empire of Rome from 264 a. C. until century III d. C., and (6) The Roman Empire to its fullest extent. The maps are in color, presented clearly, visibly and on good quality paper. In Figure 3, I show one of the maps:

Source: Reproduced by the author from FASCI ALL’ ESTERO, 1932, maps at the end of the work.

Figure 3 Map of the ‘Roman Empire to its fullest extent’

The Istituto Geográfico De Agostini was recognized for the quality of the maps made and, as mentioned, produced several materials that supported schools in Italy and abroad. In the case of the work ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’, it is relevant to recognize that, even though it is a work of a few pages, its target - Italian youth abroad - makes the search for fascistization evident. It is true that appropriations are a sensitive matter that it has not yet been possible to identify in the investigative process due to the absence of documents. But the circulation of the book was wide; it was distributed through the consulates, and from them to consular agents who passed them on to schools, libraries and reading rooms in associations and cultural centers. Analyzing aspects of the same work, Giron (1998, p. 101) concludes: “there does not seem to be any doubts about the recipients of the work nor who owns the copyright. Fascism knows to whom it directs its works and what message must be sent. Links with Italy are ensured in the works aimed at young “Italians abroad”.” And its circulation was considerable, not only in Brazil, but in America and beyond.

Further Considerations

The challenge of understanding the educational and cultural policies of Italy and its link with the Brazilian and Rio Grande do Sul contexts during the 1920s and 1930s, paying special attention to the policies, production, circulation and distribution of schoolbooks produced during fascism for ‘Italian schools’ abroad’, allows us to follow several analytical paths. In this article, two movements were chosen, a broader one seeking to understand Italian policies and their relations/resonances in Brazilian lands, especially in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and a second one, with the delimitation in the analysis of a significant work by the relation that constitutes it: (a) published under the direction of the fasci all’estero; (b) linked to the myth of Romanity and taken as so dear by the fascists; and (c) for having been directed at ‘Italian youth abroad’.

It is true that the expansion of public schools and the significant presence of confessional educational institutions in the Rio Grande do Sul context, especially in the Italian colonial area, somehow frustrated the advance and attempts of fascism to institute ‘new schools’. There was no room for what they proposed - the propaganda of fascism and the constitution of a feeling of belonging for the little ‘Italians abroad’, even though they were already a second generation born in Brazil. The ‘good neighbor policy’, so strong between Brazilian and Italian authorities, did not prevent the closure, in 1938, of all 5 Italian schools that still existed in Rio Grande do Sul. The imposition of nationalization laws and Brazil joining the Second War against the Axis countries, in 1942, caused many of the materials, books, associations, the fasci all’estero and a whole set of cultural practices to be subsumed from the public horizon.

In conclusion, I recall Chartier (2014, p.30), who, in a provisional sense, thinks of culture as the process that “articulates symbolic productions and aesthetic experiences, removed from the urgencies of everyday life, with the languages, the rituals and the behaviors, because of which the community revives and reflects its relationship with the world, with others and with itself”. Thus, is it proper to think that cultural practices articulated by fascism were mobilized in the Rio Grande do Sul context between immigrants and descendants transformed into ‘Italians abroad’? If, for a few years, the celebration of September 20 was a common date between Rio Grande do Sul people and Italians, if the ‘hero of both worlds’ represented by Garibaldi brought them together and generated consensus, many disputes and tensions were also present in this story. What meaning was attributed and what effects were possible, when decades already separated a good portion of the descendants from the distant Homeland? When reading works such as ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’ and dozens of others sent and distributed, was there any identification with Italianity? I agree with Bertonha that “[...] only a small portion of emigrants was converted into militants of the Fasci italiani all’estero, and that, of these, the majority consisted of members of the local Italian bourgeoisie and middle classes” (BERTONHA, 2001, p. 43). Many others were openly anti-fascist, and some, especially those from rural areas, struggled in their daily lives to survive, with little concern for the political colors.

Finally, I resume the challenge proposed by Chartier (2010, p. 52) for the continuity of the investigation, when considering the importance of “linking the power of writings to that of the images that allow reading them, listening to them or seeing them, with the socially differentiated mental categories, which are the matrices of classifications and judgments” to think that “a text only exists if there is a reader to give it a meaning” (CHARTIER, 2017, p. 11). I continue to search for records of uses, appropriations by immigrants and descendants of the many works that circulated, of these materialities full of senses kept in personal and institutional collections that instigate us, in order to know the singularities of the history of Brazilian education, but beyond national borders.

REFERENCES

ASCENZI, Anna e SANI, Roberto. Il libro per la scuola tra idealismo e fascismo. Milão: Vita e Pensiero, 2005. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, A. From the Mediterranean to the Americas. Italian Ethnic schools in Rio Grande do Sul between emigration, colonialism and nationalism (1875-1925). In.: Sisyphus- Journal of Education, V. 4, 2016, pp. 144-172. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, A.; LUCHESE, T. Â. Nationalism and schooling: between italianity and braziliity. Dispute in education of italian gaucho people (RS, 1930-1945). History of Education and Children’s Literature, v. XII, n. 2, p. 443-475, 2017. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. Os livros escolares como instrumentos para a promoção da identidade nacional italiana no Brasil durante os primeiros anos do fascismo (1922-1925). Hist. Educ. (Online), Porto Alegre, v.20, n.49, 2016, p.81-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/60384 [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. The construction of national identity in textbooks for Italian schools abroad: the case of Brazil between the two World Wars. History of Education & Children’s Literature, Macerata, v. 10, n. 2, 2015, p. 425-461. [ Links ]

BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara e TAMBARA, Elomar Antonilo C. A nacionalização do ensino e a renovação educacional no Rio Grande do Sul. In QUADROS, Claudemir (org.). Uma gota amarga: itinerários da nacionalização do ensino no Brasil. Santa Maria, RS: EdUFSM, 2014. [ Links ]

BENEDUZI, Luis Fernando, “Uma aliança pela pátria: relação entre política expansionista fascista e italianidade na comunidade italiana do Rio Grande do Sul”. Dimensões, vol. 26, 2011, p. 89-112. [ Links ]

BERTONHA, João Fábio. O fascismo e os imigrantes italianos no Brasil. Porto Alegre: PUCRS, 2001. [ Links ]

BEVILACQUA Piero; DE CLEMENTI, Andreina; FRANZINA, Emilio (orgs.). Storia dell’emigrazione italiana: ii arrivi. Roma: Donzelli, 2009. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger (org.). Práticas de leitura. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2009. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história ou a leitura do tempo. 2ª ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2010. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A mão do autor e a mente do editor. São Paulo: Unesp, 2014. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A ordem dos livros. Livros, autores e bibliotecas na Europa entre os séculos XIV e XVIII. 2ª ed., 4ª reimpr., Brasília: ed. da UNEB, 2017. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. Os desafios da escrita. São Paulo: ed. Da UNESP, 2002. [ Links ]

CHIOSSO, Giorgio (dir.). TESEO’ 900: editori scolastico-educativi de primo novecento. Milano: Editrice Bibliografica, 2008. [ Links ]

CHIOSSO, Giorgio. Libri di scuola e mercato editoriale: dal primo ottocento alla Riforma Gentile. Milão: Franco Angeli, 2013. [ Links ]

CHOPIN, Alain. Pasado y presente de los manuales escolares. In: BERIO, Julio Ruiz. (ed). La cultura escolar de Europa. Tendências históricas emergentes. Madrid: Ed. Biblioteca Nueva, 2000, p.105-141. [ Links ]

COLIN, Mariella. I bambini di Mussolini. Brescia: La Scuola, 2012. [ Links ]

FASCI ITALIANI ALL’ ESTERO. Quando il Mondo era Roma. Novara, Itália: Istituto Geografico De Agostini S.A., 1932. [ Links ]

FLORIANI, Giorgio. Scuole italiane all´estero: cento anni di storia. Roma: Armando, 1974. [ Links ]

FRANZINA, Emílio; SANFILIPPO, Matteo. Il fascismo e gli emigranti. Bari: Laterza, 2003. [ Links ]

GALFRÉ, Monica. Il regime degli editori: libri, scuola e fascismo. Roma: Laterza, 2005. [ Links ]

GIRON, Loraine Slomp. Colônia italiana e educação. Hist. Educ. (Online), Porto Alegre, v. 2, n. 3, 1998, p. 87-106. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, T. Â (org.). Escolarização, culturas e instituições: escolas étnicas italianas em terras brasileiras. Caxias do Sul: EDUCS, 2018. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela (org.). História da escola dos imigrantes italianos em terras brasileiras. Caxias do Sul: EDUCS, 2014. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. Da Itália Ao Brasil: Indícios da Produção, Circulação e Consumo de Livros de Leitura (1875-1945). Hist. Educ. [online]. 2017, vol.21, n.51, p.123-142. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/68894 [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. O processo escolar entre imigrantes no Rio Grande do Sul. Caxias do Sul, RS: EDUCS, 2015. [ Links ]

MEDICI, Lorenzo. Dalla propaganda alla cooperazione: la diplomazia culturale italiana nel secondo dopoguerra (1944-1950). Italia: Antonio Milani, 2009. [ Links ]

MORANDINI, Maria Cristina. Istituto Geografico Giovanni De Agostini. In: CHIOSSO, Giorgio (dir.). TESEO’900. Editori scolastico-educativi del primo Novecento. Milano, Itália: Editrice Bibliografica, 2008, p. 260 - 271. [ Links ]

PRETELLI, Matteo. Fascist textbooks for Italian schools abroad. Biennal Conference of the Autralasian Centre For Italian Studies, 5, 2009. Congress proceedings… Auckland: Australasian Centre for Italian Studies. Disponível em http://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au Acesso em 17/04/2020. [ Links ]

PRETELLI, Matteo. Il fascismo e gli italiani all’estero. Bolonha: Clueb, 2010. [ Links ]

RECH, Gelson L. Escolas étnicas italianas em Porto Alegre/RS (1877-1938): a formação de uma rede escolar e o fascismo. Pelotas: UFPel, 2016. 449f. Tese (doutorado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas. [ Links ]

SALVETTI, Patrizia. Immagine nazionale ed emigrazione nella Societá Dante Alighieri. Roma: Bonacci, 1995. [ Links ]

SALVETTI, Patrizia. Le scuole italiane all‟estero. In: BEVILACQUA Piero; DE CLEMENTI, Andreina; FRANZINA, Emilio (orgs.). Storia dell’emigrazione italiana: ii arrivi. Roma: Donzelli, 2009, p. 535-549. [ Links ]

TARQUINI, Alessandra. Storia della cultura fascista. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2011. [ Links ]

TRENTO, Angelo. Do outro lado do Atlântico: um século de imigração italiana no Brasil. São Paulo: Nobel; Istituto Italiano di Cultura di San Paolo; Instituto Cultural Ítalo-Brasileiro, 1989. [ Links ]

ZAGO, Octávio S. “Hemos Hecho Italia, Ahora Tenemos Que Hacer a los Italianos”. El Aparato Educativo Transnacional Del Régimen Fascista Italiano, 1922-1945. História Mexicana [on-line]. 2020, vol.69, n.3, pp.1189-1246. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24201/hm.v69i3.4021 [ Links ]

1With the support of CNPq and Fapergs. English version by Maria Dolores Dalpasquale. E-mail: dolorestradutora@gmail.com.

2The Dante Alighieri Society was created in 1889 by Giacomo Veneziam with the proposal of protecting and diffusing the Italian language and culture outside the Kingdom, particularly by subsidizing and establishing schools and libraries. According to Salvetti (1995 and 2009), the Society promoted ‘moral bread’ to emigrants, concerned with providing conditions for an educational and cultural formation.

3According to Barausse (2015, 2016, 2017), in order to leverage the action of religious organizations, the Associazione Nazionale per soccorrere i missionari italiani emerged at the end of 1886 and operated on several continents at the initiative of Ernesto Schiaparelli. In 1909, in Turin, the federation of religious congregations active in the field of assistance to immigrants residing in the Americas was established. Almost all Italian religious orders and congregations joined and mobilized to organize and promote Italian national interests through the dissemination of the Italian language and culture by founding new schools.

4The Fasci all’estero were sections of the National Fascist Party installed outside Italy. They were groups organized and fostered by fascist policies for propaganda and diffusion of the ideology among Italian communities abroad, trying to co-opt and mobilize them. They also developed assistance and cultural activities, ceremonies in defense of Italianity and fascism (FRANZINA and SANFILIPPO, 2003; PRETELLI, 2009 and 2010; BERTONHA, 2001).

5The Dopolavoro all’estero were associations aimed at workers abroad and which became “a very effective means of drawing Italians abroad closer to fascism, through recreation, sports and culture”, reports Bertonha (2001, p. 46).

6Piero Parini arrived in Brazil to strengthen ties and cultural exchanges. He visited Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul. In the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, he was welcomed by numerous authorities and, in his honor, dinners and musical performances were offered; he also visited several conational enterprises, as well as colonial areas in RS. In addition to Brazil, he went to Argentina and Chile.

7Bastos and Tambara also inform that: “The expansion of the public school network came along with measures to enhance the apparatus of education in Rio Grande do Sul. This meant restructuring the system, centralizing it in such a way that it achieved the pedagogical modernization advocated by the renewal movement started in 1937, homogenizing educational guidelines” (2014, p. 91). Further on, the same authors emphasize that “a series of technologies were employed: courses, seminars, lectures, pedagogical missions, guidance subsidies, announcements. They contributed more to organizing the regulatory processes of pedagogy, in search of a scientific organization of the education administration, than to promoting the autonomy and creativity of teachers, as the work turned to pedagogical practices conceived elsewhere. The CPOE/RS was established as a place that, at the same time as it produced and disseminated knowledge in the pedagogical field, established itself as a field for the conception or application of this knowledge” (BASTOS and TAMBARA, 2014, p. 109).

8In June 1900, the owners of a graphic arts house in Aarau, Switzerland, Jaques Muller and Augusto Trub, opened a branch in Como, commune of Lombardy, which was under the responsibility of Giovanni de Agostini and Arturo Reslieri, and had a cartographic section. Such initiative, according to records, though ephemeral, as in 1901 it was already in the process of closing, started what would be a successful experience in the publishing field for De Agostini, according to Morandini (2008, p. 260). With the bankruptcy of Muller and Trub’s branch, De Agostini decided to continue with the ‘Istituto Cartográfico De Agostini’, or also the ‘Istituto Italiano Cartográfico’. With the support of associates, in 1909, he moved the institute’s headquarters to Novara and opened a branch in Turin. In 1919, De Agostini went through financial problems and took on the role of scientific director. The business is partially closed in April 1920. But it starts to appear as managed by associates. De Agostini is left with small works until 1937, when Italgeo was founded. De Agostini carried out several support works for primary schools through maps, geographic atlases, school manuals, wallcharts, etc. The search for expanding the publishing house’s typographic business takes them overseas, and they opened branches in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, for instance (MORANDINI, 2008).

9“Brief news about a small people who knew how to give the world a great civilization” (free translation by the author).

10“Dedicated to the Italians living abroad and who, before foreigners, must uphold the honor and honor of being the great heirs of ancient Rome” (free translation by the author).

11“The reproduction of both the text and illustrations remain the exclusive property of the Fasci all’Estero” (free translation by the author).

12Tarquini explains (2011, p. 128) “non vi era l’emblema del fascio littorio, un mazzo di verghe di betulla tenute insieme da nastri di cuoio simbollegiante il potere di punire esercitato dai magistrati romani, ma um pugno chiuso che serrava spighe di grano” [the emblem of the fascio littorio was not a handful of birch sticks held together by leather bands symbolizing the power to punish exerted by Roman magistrates, but a clenched fist that clenched wheat ears.].

Received: November 17, 2021; Accepted: February 15, 2022

text in

text in