Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-67

Papers

Architecture, school culture, and physical education practices: the relevance of patios in Salesian institutions in the early 20th century1

1University of Campinas (Brazil). diego.edfisica.ferreira@gmail.com

2University of Campinas (Brazil). gois@unicamp.br

This research aimed to analyze the representation of the patio as a school space of Salesian educational institutes, in particular, the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa and the Liceu Coração de Jesus. The study had as its time frame the first decades of the 20th century, and the documentary research had as sources: yearbooks, record books, and photographs. From the analysis of the data, we observed that physical education practices were very present in those patios, engaged by an interrelation process between different school cultures, inspired by modern pedagogies and a Catholic educational project.

Keywords: History of schools; School architecture; Physical education

A presente pesquisa teve como objetivo analisar a representação do pátio como constituinte do espaço escolar de estabelecimentos educacionais salesianos, em específico, o Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa e o Liceu Coração de Jesus. Em um recorte temporal pertinente às primeiras décadas do século XX, a pesquisa documental teve como fontes: anuários, livros de registro e fotografias. A análise dos dados permitiu observar que nos pátios salesianos as práticas de educação física estavam muito presentes, e envolvidas em um processo de inter-relação entre diferentes culturas escolares marcadas por pedagogias modernas e um projeto educacional católico.

Palavras chave: História das instituições escolares; Arquitetura escolar; Educação Física

Esta investigación tuvo como objetivo analizar la representación del patio como un componente del espacio escolar de los establecimientos educativos salesianos, en particular, el Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa y el Liceu Coração de Jesus. En un marco de tiempo pertinente a las primeras décadas del siglo XX, la investigación documental tuvo como fuentes: anuarios, libros de registro y fotografías. El análisis de los datos permitió observar que en los patios salesianos las prácticas de educación física estaban muy presentes e involucraban un proceso de interrelación entre las diferentes culturas escolares marcadas por las pedagogías modernas y un proyecto educativo católico.

Palabras claves: Historia de las instituciones escolares; Arquitectura escolar; Educación Física

Introduction

This research aims to analyze the representation of the patio as a school space of Salesian educational institutes, in particular, the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa and the Liceu Coração de Jesus. The historiography of Brazilian school architecture has recently gained importance in research and, for Ermel and Bencostta (2019a, p. 2), “some gaps need to be better investigated, both from the point of view of time frames and new thematic prospects.” In this particular discussion, Ermel and Bencostta (2019a) state that the gaps in this field still lie in the need to clarify how the circulation of pedagogical ideas occurred internationally compared to national and regional perspectives at different times, but especially in the late 19th century and early 20th century2. We do not intend to fill these gaps, but to analyze in an original way the patio as an element of school architecture and its relationships with a pedagogy translated into physical education practices (GOIS JUNIOR; SOARES, 2018).

In this study, as a time frame, we chose the first three decades of the 20th century, a time when school spaces (buildings and houses) underwent major reforms in an attempt to respond to the new social demands linked to the modernization discourses of the main Brazilian cities (BENCOSTTA, 2005). According to Silva, Rizzini, and Silva (2012), school spaces and their architecture were part of the project to remodel the population’s behavior and customs.

The choice of these institutions is justified because both are characterized as the first Salesian educational institutions in the 19th century on Brazilian soil, being responsible for the education of a significant number of young people from the elites of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, in Niterói, was the first teaching institution of this Catholic congregation, founded in Brazil in 1883. The Liceu Coração de Jesus, based in the city of São Paulo, was founded in 1885. The organization of these first two schools was followed by the foundations of institutions in the cities of Recife, Campinas, Lorena, and Cuiabá, still in the 19th century (CASTANHO, 2008).

By a theoretical perspective identified with cultural history (BURKE, 2008), one can see the patios of these institutions as a materialization of a school culture (JULIA, 2001), in particular, constituted within the scope of a Catholic congregation. According to Julia (2001), although school culture represents “a set of norms that define knowledge to teach and behaviors to inculcate, and a set of practices that allow the transmission of this knowledge and the incorporation of these behaviors” (p. 10), one can also include children’s cultures in this context, “which develop in playgrounds” (JULIA, 2001, p. 11). In this sense, from the perspective of Dominique Julia, a religious school can no longer be just a place of knowledge but also become a place of incorporation of behaviors and habits that transcend Christian education and disciplinary learning (FARIA FILHO; VIDAL; PAULILO, 2004). Furthermore, it must be said that school culture is now understood in its plurality. In other words, we are talking about school cultures, since one has to consider, according to the study object, the experiences of teaching, learning, coexistence, socialization, regulation, and subversion, which enable the problematization of the institutionalization processes of the school at its different levels and teaching modalities (VIDAL, 2007). The study of school cultures considers the ways in which subjects relate to practices, as the school is a place of constant negotiation between what is imposed and practiced (VIDAL, 2005; 2007).

From this perspective, the analysis of architecture and school space transcends a traditional approach, since it allows the interpretation of other discourses embodied in the practices that were organized in those spaces (VIÑAO FRAGO; ESCOLANO BENITO, 2001). Thus, we seek to study the Salesian patio as a cultural construct that reflects, beyond its materiality, certain pedagogical discourses.

For the interpretation and constitution of this narrative, access to the institutions’ historical collection was of paramount importance. In both institutions, the dialogue was carried out by school yearbooks, register books of the main events during a year; iconographic materials that portrayed their daily lives under Salesian lenses; and official documents of the institutions, which constitute their memory.

The arrival of the São Francisco de Sales Congregation in Brazil at the end of the 19th century and the development of its educational institutions directly dialogued with the reflections on the Brazilian educational system that were in the air at the turn of the century. At the beginning of the new century, the Salesians already had educational institutions in the main Brazilian states (AZZI, 2002), and intermediated in their practices the rules proposed for the school environments of that period.

School education would be one of the fundamental elements for the construction of the new Brazilian political and economic scenario, the Republic. School has become one of the main instruments for disseminating new habits and behaviors considered appropriate.

If the Republic was the place of the new man, it became necessary to rethink this environment, organizing it, sanitizing it, that is, ordering the physical space of the city and, consequently, the physical space of the school. School buildings appear, at that time, with a specific purpose - the place where the formation of the citizen takes place (DÓREA, 2013, p. 169).

Therefore, it was necessary to build proper environments for a new school education (BENCUSTTA, 2001; 2005). According to Faria Filho (1998), in large urban centers, the construction of the school will then be closely linked to the symbolic construction of the city and the reformulation of the republic. The locations of the new school buildings stood out as a representative figure of the new times.

Inserted in this scenario, the Salesian Congregation had specifications for the construction of its educational institutions in the daily life of the city. According to Higino (2006), the congregation prioritized in its choice places that would provide protection and potential growth for its projects. Thus, the Salesian educational institutions spread first to centers and capitals, as in the case of the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa in Niterói, capital of Rio de Janeiro, and the Liceu Coração de Jesus, in the capital of São Paulo, both inaugurated at the end of the 19th century.

The schools started to be built with the most modern pedagogical, hygienic, and architectural precepts. These prerogatives expose the project for the construction of these new school buildings to a perspective that goes beyond the educational field. In the new project for Brazilian education, the dialogue between various sciences and a health-aware school would be present in the constitution of its institutions, based on norms and rules stipulated by hygiene as standards for living well (ROCHA, 2017). In architectural matters, these new buildings were built to be seen, admired, and revered, serving as an example to other institutions, and to work as modelers of habits, attitudes, and sensitivities (FARIA FILHO, 1998).

Salesian buildings did not fall short of these standards. Its institutions were represented by grandiose facades, announcing their modern constructions and internal spaces that would respond to the needs of a specific space for the education of Brazilian childhood. The Liceu Coração de Jesus represents this dialogue perfectly. As an example to other Salesian educational institutions, the architecture of the Liceu Coração de Jesus in São Paulo received mentions in several documents of the congregation itself. A passage entitled Lyceu Salesiano - As nossas impressões, a text published in the yearbook of the sister institution Lyceu Nossa Senhora Auxiliadora de Campinas, describes in detail the admired architecture of this establishment.

The building consists of a central body, one on the left with three floors, another on the right, and a magnificent hall, destined for future physical education, museums, and classrooms.

The central body is Roman in style, with three floors.

The entrance is charming in appearance, with a large atrium at the front and a circular hallway that serves as a playground in rainy weather[...].

Behind the building are beautiful avenues, a beautiful orchard, and a pleasant park for sports games. (LYCEU SALESIANO NOSSA SENHORA AUXILIADORA, 1914, p. 31).

It was by this representation in the search for an education beyond the wall and the modulation of social habits that the school buildings began to constitute, with all their grandeur and magnitude, the urban spaces where a youth belonging to the most privileged social strata of those cities lived and circulated. The new educational institutions were built along the path of the political and economic elite of the great centers.

The rapid consolidation of the Salesian Congregation as an articulated educational system in Brazilian territory was caused by several factors present in the socio-political and economic scenario of the country. Among them, we can mention the need to expand the educational system, a conception of education aimed at professional teaching (training of workforce), attention to youth, and the preservation of the Church’s dogmas. Despite the liberal thoughts that circulated in the elite sectors of society at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, the Church remained a strong institution in the definition of social values (NAGLE, 2001). In the same direction, Cunha (2009) explains that the failure of the abolitionists, who aimed to train the workforce from the schooling of the new freed slaves, gave way to the preferences of the ruling classes, who granted this role to religion and, preferably, to the Catholic Church.

Thus, the Salesians constituted at the beginning of the 20th century a strong network of educational institutions considered to be references in the education of Brazilian youth. This occurred, particularly, by its initiatives of moral, professional, and religious education, prioritizing the instruction of the youth. A particularity of the Salesian educational project was the relevance of practices that could foster youth protagonism, such as games and recreational activities. However, we observed a diversity of physical education practices in the sources (GOIS JUNIOR; SOARES, 2018). In this study, sports, games, and gymnastics were all understood as cultural practices to which a Catholic educational institution imprinted its values through appropriations. These practices (CERTEAU, 2011) - which here will be established by the expression physical education practices - are constituted and dialogue with different identities, such as religious ones.

However, these practices were present in certain spaces, where their architectures are problematized and present demands for city modernization. Between bricks and pedagogies:

The school in its different embodiments is a product of each time, and its constructive forms are, in addition to the supports of collective and cultural memory, the symbolic expression of the dominant values in different times (VIÑAO FRAGO; ESCOLANO BENITO, 2001, p. 47).

The school, from a cultural bias, becomes a creation of society itself, being subject to historical changes (VIÑAO FRAGO; ESCOLANO BENITO, 2001). Therefore, the study of the school space brings us closer to the representations and appropriations of its path (CHARTIER, 1990). The possibility of analyzing the school space recovers the history of institutions, giving possibilities to different interpretations (DÓREA, 2013). The school space, beyond its architecture that represents a historical moment, has an educational dimension in itself. This dimension is ratified by Faria Filho (1998), who identifies in this space a discourse that institutes a system of values in its materiality.

The school space, built from architecture, environments, and experiences, is identified as an educating program, that is, an invisible, silent, and hidden element of the curriculum. Thus, it reflects a certain discourse that aims to guide educational practice.

In the approximation of the Salesian daily life from the constitution of the spaces of its institutions, one can observe the educational action of their structures, mainly in the distribution of their environments. By an educational philosophy preached by Don Bosco, in which physical education practices were encouraged in the educational process of young Salesians, some spaces gained prominence in the educational institutions of the congregation. In Salesian education, school architecture, paying attention to the distribution of its spaces, assumes the educational values propagated by the Congregation of Don Bosco. Explicitly or implicitly, it takes part in the modulation of the habits and behavior of young Salesians. Viñao Frago and Escolano Benito (2001) describe this relationship as follows:

School architecture is also in itself a program, a type of discourse that institutes in its materiality a system of values, such as order, discipline, and vigilance, which are milestones for sensory and motor learning and a whole semiology that covers different aesthetic, cultural, and also ideological symbols (p.26).

In these criteria, a space inside the Salesian buildings was highlighted in the educational program: the patio. The patio was responsible for materializing an important part of the philosophy proposed by Don Bosco to his followers. In it, the various practices of physical education, collective and recreational activities, celebrations, and presentations were experienced. The patio identified the Salesian institution.

However, when mentioning the patio, the constitutive space of Salesian educational institutions, we must not limit it to a physical space with masonry walls that occupies the central area of the establishment. In Fonseca’s (1998) reflections, the concept of patio in the Salesian tradition expands, being synonymous with movement, youth, joy. In particular, any open environment, with a good dimension for the practice of games and competitions, which allowed for gatherings of students, was considered a patio. Therefore, these environments spread within the Salesian institutions.

Protagonism of the patio at Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa

The Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa was the first educational institution of the São Francisco de Sales Congregation on Brazilian soil. Founded in 1883, the institution regularly received students in early 1884. Located in Niterói, capital of Rio de Janeiro, the school reaches the first decades of the 20th century characterized as a large school establishment present in the daily life of Rio de Janeiro.

As a Salesian institution, the school followed the guidelines propagated by Don Bosco to his entire Congregation. They included: openness to games, sports, dance, parties, and the youth movement, pedagogical instruments that, for the priest, made the schooling process more pleasant.

In the case of Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, the set of buildings that housed the institution presented itself, after several renovations and new constructions in the early 20th century, as a major architectural work that would meet all the specifications required for the period. Wide corridors, large windows, airy and well-lit classrooms, science laboratories, infirmary, dental office, dormitories, cafeterias, and patio, spaces for the passage and stay of Salesian students.

Responding to the new demands placed on the school environment by hygienist precepts (STEPHANOU, 1999; ROCHA, 2003; GONDRA, 2004), Salesian architecture was molded to the discourses of doctors and engineers disseminated in different sectors of society in the name of a modern Brazil (HERSCHMANN; PEREIRA, 1994). In several passages of its yearbooks, documents, and reports, the term “hygiene” is presented as a description of the institution’s internal environments.

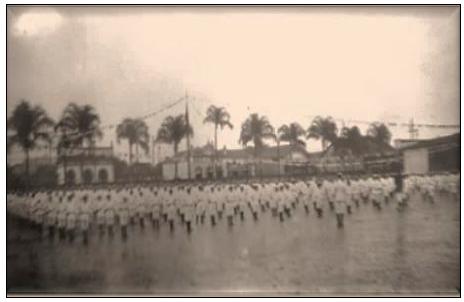

In view of the exhibition of its physical spaces, some environments in particular gained prominence: the wide open spaces, the sports fields, and the large patios. These spaces were primarily intended for experiencing the various physical education practices that characterized the educational system created by Don Bosco.

Higino (2006) reports that these environments were, in the construction of the school, virtually mandatory, dialoguing with the pedagogy of games proposed by Don Bosco to young people in his institutions. At the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, specifically, the organization of its spaces took place as follows:

The land of more than 100,000 m2 was occupied by a series of solid buildings, well ventilated and adapted to the requirements of a good school, with wide and tree-lined patios for each of the six student divisions, fields for games, theater hall for dramatic performances and conferences, laboratories, offices, and museums. (HIGINO, 2006, p.25)

Later, entering the first decades of the 20th century, with the growth and development of the various sports practices in the city, the Colégio Salesiano would house in its interior the mark of these new social practices. Thus, the wide spaces, patios, and fields, which initially promoted games and free movement, became specific places for certain sports practices.

The open spaces, patios, and fields gained lines, beams, nets, several balls, rackets, wheels, and various instruments of modern sporting events. Sports, already enshrined in the city’s daily life, were increasingly present in the internal spaces of the school. According to Melo (2019), sports provided a new entertainment sensitivity in the city of Niterói in the 1890s. From these environments, one can see the relationship that the educational institution developed with the daily life of the city in which it was inserted. Its internal spaces became the representation of this dialogue.

At the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, the alterations carried out in its spaces, mainly those responsible for the experience of physical education practices, reveal in a striking way an educational project that gave more space to pedagogies considered modern, such as sports. In 1927, a proposal drawn up by the Salesian superiors, aiming to make sports teaching official, argued with the following presentation of the institution:

Considering that this institute, perfectly equipped with its own buildings, which are hygienic and adequate, have offices for natural, physical, and chemical history, sports fields, and other modern pedagogical needs, fulfills the purposes of education and instruction;

Considering that this institute thus meets all the requirements of suitability for the exact performance of its high cultural mission, and provides an inestimable sum of benefits to the education of destitute or needy childhood (COLLEGIO SALESIANO SANTA ROZA, 1927, s.p.).

The observation of the spatial distribution of Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa allows for different analyses that precipitate the institutions routine. In the presence and absence of the walls of its buildings, there is an increase in hygienic practices, the legacy left by Don Bosco in the patios, and the presence of modern sports in specific spaces. All these spaces were filled daily by several students, who gave life to every meter of the institution. The spontaneous and free movements of the countless students received by the missionaries gave the Salesian school day a unique moment in the life of each participant.

The protagonism of the patio at the Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa accompanies the entire course of the institution from Niterói. In each reform, change, adaptation, celebration, tribute, competition, the patio would be represented in the institution’s daily life.

The patio as a privileged space for these practices constituted a rich contact zone, as an area of convergence of different school cultures. In the encounter between the Salesian tradition inspired by the pedagogy of Don Bosco and the pedagogical discourses of the modern school guided by the government, we understand that physical education practices were not just prescriptions, since they asserted themselves between different school cultures and gained new dynamics from the experiences of students.

Protagonism of the patio at Liceu Coração de Jesus

The second educational institution analyzed in this study was the Liceu Coração de Jesus, founded in the late 19th century in the city of São Paulo. Unlike the land for the construction of the institution in Niterói, the acquisition of the space for the construction of the project in São Paulo did not start at ground zero. The Salesians took over a constructed building in the capital of São Paulo, which was a High School project for the city of São Paulo that was not concluded (ISAÚ, 1985).

Little by little, the building located in Campos Elíseos gradually gained the features and characteristics of a Salesian teaching institution. Between works and renovations, an imposing building gained the specific contours of the Congregation and, slowly, the façade, the internal spaces, the spatial distribution, and the entire structure acquired the peculiarity of the teaching institutions of Don Bosco.

Regarding the physical structure of the Liceu Coração de Jesus, a specific space was also the protagonist there: the patio. As already discussed, one of the characteristics of Salesian educational institutions is juvenile games, music, movement, and joy (AZZI, 1982).

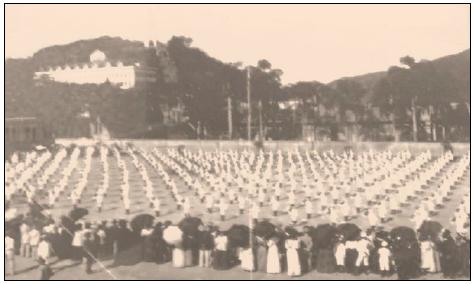

Thus, the concern with physical education practices was relevant, since the floor plan of the grandiose architectural complex of Liceu Coração de Jesus featured large outdoor spaces, such as fields, courts, and patios. The description of these spaces was frequently reported in documents, leaflets of the time, and the yearbook of the Salesian institutions. But, in particular, the patio was best represented the joy and free movement proposed by Don Bosco’s pedagogy. It was in this space that the various physical education practices were experienced by Salesian students. The patios of the Liceu Coração de Jesus were a representation of the juvenile movement within the institution. When the students came back to school, it was this environment that announced the return of the school’s daily life.

The patios, days before so little animated, regained the joyful and tumultuous life of the past. And what movement! Last year there were about 380 or so; this year there are 450 who move and shake, who talk and laugh, who jump and run every day. (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1916, p.7).

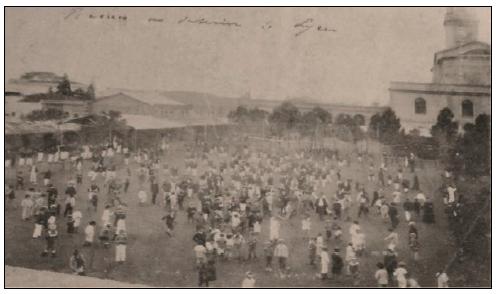

At the Liceu Coração de Jesus, the patios were used mainly for the youth’s moments of recreation. In those moments, without any solemnity or special event, the patio was photographed and registered in the official documents that would tell the institution’s history.

Source: Liceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus (1906).

Image 5 “Estado” game between Boarding School and Day School, beginning of 1906.

Recreation in the patio was not an official solemnity or formal event, but it was at this time that one of the greatest characteristics of the congregation was present. It was in this space that free movements were also practiced by students, an aspect that Don Bosco always emphasized in his teaching institutions.

Source: Liceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus (1908).

Image 6 Recess at the patio of the Liceu Coração de Jesus, 1908.

The photographs above show the prominence given to the dynamics of the Salesian patio in two different moments. The first, in 1906, shows the Liceu patio as a large open area without many constructions or boundaries. Since its foundation, at the end of the 19th century, up to the limit of the time frame of this research, in 1930, the Liceu went through several reforms, making the school more and more suitable for the education of São Paulo’s youth. The simplicity of the terrain did not prevent the practice of games, movements, and moments of recreation among the Salesian students.

The other moment illustrated by the photograph above is of a more institutionalized Liceu, with a greater number of students in its patio. However, the way of practice experienced in this environment did not change; the patio continued to be the materialization of a pedagogy centered on recreational games, but also on sports and gymnastics. The image as an instrument for preserving the institution’s memory captures aspects that characterize it and create its identity.

The photographs express the trajectory of the construction of the Liceu, from the establishment donated to the Congregation at the end of the 19th century to the imposing school building at the beginning of the 20th century. The renovations for the construction and improvement of its spaces were continuous, always aiming at the best way to develop Salesian education and respond to the needs demanded by the public authorities. Amidst the entire process of renovations and constructions, the patio was always highlighted. The reform that took place in 1918 is reported in the yearbook as follows:

And the vast two-story house of large classrooms, full of air and overflowing with light, was undoubtedly a beautiful novelty for the newcomers.

The expansion of the patios, due to the land gained from the demolition of the mechanic and carpentry workshops, which had been transferred to Bom Retiro, was another development that students appreciated even more than the new building, since the acquisition of more a few hundred square meters to run, jump, play, in wider and more capricious lines and curves, was for them an achievement of value only comparable to the terrain that, inch by inch, is disputed with the enemy on the battlefields (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1918, p.5-6).

The patio was almost always present in the renovations, with the aim of adapting the physical space of the Liceu more and more to the educational requirements of the time and to the Salesian educational methods. Other reforms that took place in the institutions highlighted the living spaces, such as the free and open areas and the terraces. In the construction of the new building, once again, spaces for recreation were highlighted. “An important part of the new construction is the large terrace, intended to be the patio for the semi-boarding students. It measures 520 square meters. From there, a magnificent landscape is unfolded. It will be a hygienic and loose playground, with no dust and no soccer balls.” (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1925, p.6).

The 1925 yearbook reported that the patio seemed small for the number of students, so that the terraces were used to enlarge the spaces, decongesting those spaces during the hours aimed at recreation. One option for better coexistence was to divide the students’ recess into two periods. The Liceu registered over 10,000 square meters of open areas for recreation and the experience of various physical education practices, and this dimension was achieved by the following measures:

Total area of the Liceu court: 15,200 m2.

Total built area: 5,500 m2.

Outdoor area for recreation: 7,235 m2.

Covered playground area (porches): 2,465 m2.

Terrace area of the Day School: 520 m2.

Hence it is concluded that the Liceu has 10,220 m2 for recreation. (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1925, p.6).

The various reforms carried out at the beginning of the 20th century, which generally highlighted the issue of patios and recreation spaces, were pervaded by hygienic precepts that hovered in the daily life of large urban centers, which in turn were adopted by educational institutions. In the documents responsible for exposing and disclosing the renovations and their needs to São Paulo society, the hygienic conditions were present in the students’ ample accommodations, in the airy rooms, and in the terraces without the dust of the dirt fields.

The hygienic requirements present in large cities at the beginning of the 20th century implemented guidelines in educational institutions, which were encouraged and disseminated by public authorities, doctors, and intellectuals (SOUZA, 1997; STEPHANOU, 1999). The Liceu, which in number of students was already the main Salesian institution on Brazilian soil, often depended on popular and governmental donations to maintain itself and carry out its educational work. Therefore, it could not escape the hygienist precepts propagated by doctors, engineers, and educators (HERSCHMANN; PEREIRA, 1994). Hygiene, in addition to being a requirement, became advertisement for a modern educational institution integrated with society and its new demands.

In the 1920s, the institution already demonstrated the magnificence of its buildings, which represented an open publicity for Salesian education. The 1921 yearbook, in the introduction to its Statute, described the hygienic institution based on its social environments.

Hygiene and comfort

The hygienic conditions of the establishment are excellent. Vast halls for dormitories and classrooms, abundantly served by air and light; spacious patios with plenty of areas for all sorts of outdoor games; large filtered water tanks on all premises of the institution and on all recreational patios (more than four thousand liters of filtered water constantly supply their large pressure filters); excellent sanitary facilities, washbasins with abundant running water; installations with cold and hot water; excellent modern fitting kitchen; an excellent infirmary built expressly, equipped with all modern resources, with large halls and rooms for patients; complete pharmacy and resident pharmacist in the establishment; daily medical visit from a very competent physician; first order dental office, with two in-house graduate professionals; modern barber salon, with in-house staff; in a word, all the hygiene and comfort resources that, along with moral, intellectual, and artistic education, can make collegial life at the same time healthy, fruitful, joyful, and pleasant, to form healthy and robust boys and young men, gifted in body and spirit. (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1921, p. 132).

Publicized in São Paulo society, the Liceu Coração de Jesus acquires great prestige as an educational institution. The number of students grew during its trajectory. In the year of its foundation (1885), the institution met few students from nearby villages. In 1930, according to its yearbook, the Liceu had 1280 students from different cities in São Paulo and from other Brazilian states. (LYCEU SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS, 1930).

The patio of the Liceu Coração de Jesus was the space for the manifestation of the various physical education practices that moved the institution’s daily life. From the recreation and games provided by the tradition of the Salesian Congregation to the modern sport that, from the city environment, entered the institution, the patio of the Liceu was the space for representation and mediation between different school cultures, such as the Salesian tradition, the modern school ideals, but also the particularities of each Salesian institution.

Final considerations

The mark of Salesian institutions at the beginning of the past century had as one of its main characteristics their architectural collection. Imposing buildings that, by new constructions, renovations, and adaptations, represented Salesian teaching on Brazilian soil. Inside the establishments, a space in particular gained prominence: the patio.

Defined by a broad concept, the Salesian patio was the protagonist of the main moments of the analyzed institutions: Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa and Liceu Coração de Jesus. The Salesian patio, which originated in the tradition of the Congregation of Don Bosco, was the place responsible for perpetuating the teachings of the Italian priest. Recreation, games, free movement in the patio were part of the pleasant moment that gave lightness to Salesian education. However, this did not mean the absence of sports and gymnastics marked by modern education. On the contrary, the Salesian patio was also an important mediator between different school cultures. The manifestations experienced in these spaces represented intermediations between the hygienist ideals of a modern school and the Catholic Salesian tradition. Not very far from what Cancilini (2003) observed in the field of Latin American arts, this multitemporal heterogeneity is the consequence of a history in which modernization has rarely operated by the replacement of the traditional by the modern. These contradictions were favorable so that only Brazilian elites could have access to practices considered modern, to the comforts of an urban, hygienic, rational civility, according to the prescriptions of doctors and intellectuals, but they also concurrently maintained social structures in pre-modern models, such as religious education.

Analyzing the patios of Salesian educational establishments involves us in a different process of reflection, which, based on cultural collections and on a methodology that takes advantage of new sources, such as structures and school spaces, tells another story of school institutions.

REFERENCES

ARATA, Nicolás. Un episodio de la cultura material: la inauguración de 54 edificios escolares en la ciudad de Buenos Aires (1884-1886). Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v.23, e84235, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/84235. [ Links ]

AZZI, Riolando. A obra de Dom Bosco no Brasil: cem anos de história. Barbacena: Centro Salesiano de Documentação e Pesquisa, 2002. v. III. [ Links ]

AZZI, Riolando. Os salesianos no Brasil a luz da história. São Paulo: Salesiano Dom Bosco, 1982. [ Links ]

BENCOSTTA, Marcus Levy Albino. Arquitetura e espaço escolar: reflexões acerca do processo de implantação dos primeiros grupos escolares de Curitiba (1903-1928). Educação em revista, Curitiba, n.18, p.103-141, dez. 2001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.236 [ Links ]

BENCOSTTA, Marcus Levy Albino (Org.) História da Educação, Arquitetura e Espaço Escolar. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2005. [ Links ]

BURKE, Peter. O que é História Cultural? 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editora. 2008. [ Links ]

CANCLINI, Nestor García. Culturas Híbridas: estratégias para entrar e sair da modernidade. 4. ed. São Paulo: EdUSP, 2003. [ Links ]

CASTANHO, Sergio. A institucionalização escolar entre 1879 e 1930. Série-Estudos, Campo Grande, n. 25, jun. 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20435/serie-estudos.v0i25.219. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A escrita da história. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2011. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A História Cultural: entre práticas e representações. Lisboa: DIFEL, 1990. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antonio. Educação, Estado e Democracia no Brasil. 6. ed. Cortez, Niterói: Editora da Universidade Federal Fluminense; Brasília: FLASCO do Brasil, 2009. [ Links ]

DÓREA, Célia Rosângela Dantas. A arquitetura escolar como objeto de pesquisa em História da Educação. Educação em revista, Curitiba, n.49, p.161-181, set.2013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40602013000300010. [ Links ]

ERMEL, Tatiane de Freitas; BENCOSTTA, Marcus Levy. Arquitetura escolar: diálogos entre o global, nacional e regional na história da educação. História Educ., Santa Maria, v.23, p.1- 6, 2019a. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/88785. [ Links ]

ERMEL, Tatiane de Freitas; BENCOSTTA, Marcus Levy. Escola graduada e arquitetura escolar no Paraná e Rio Grande do Sul: a pluralidade dos edifícios para a escola primária no cenário brasileiro (1903-1928). Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v. 23, e83527, 2019b. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/83527. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes. O espaço escolar como objeto da história da educação: algumas reflexões. Educação e pesquisa, São Paulo, v.24, n.1, p.141-159, jan.1998. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-25551998000100010. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes; VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves; PAULILO, André Luiz. A cultura escolar como categoria de análise e como campo de investigação na história da educação brasileira. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v.30, n.1, p.139-159, abr. 2004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022004000100008. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Jairo de Matos. Sistema Preventivo de Dom Bosco. Belo Horizonte: CESAP, 1998. [ Links ]

GOIS JUNIOR, Edivaldo; SOARES, Carmen Lucia. Os comunistas e as práticas de educação física dos jovens na década de 1930 no Rio de Janeiro. Educação e pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, p. 1-19, 2018. [ Links ]

GONDRA, José G. Artes de civilizar: medicina, higiene e educação escolar na Corte Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: EdUERJ, 2004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201844175380. [ Links ]

HERSCHMANN, Micael M.; PEREIRA, Carlos Alberto M. Invenção do Brasil Moderno: Medicina, Educação e Engenharia nos anos 20-30. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1994. [ Links ]

HELFENBERGER, Marianne; SCHREIBER, Catherina. Construindo cidadãos: arquitetura da escola e seu programa social - visões comparativas da Suíça e de Luxemburgo nos séculos XIX e XX. Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v. 23, e82303, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/82303. [ Links ]

HIGINO, Elizete. Um século de tradição: a banda de música do Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa. 2006. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro 2006. [ Links ]

IBARRA, Carlos Ortega. Una arquitectura escolar nacional y popular durante la revolución constitucionalista de 1914-1917. Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v.23, e83400, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/83400. [ Links ]

ISAÚ, Manoel. Liceu Coração de Jesus. São Paulo: Editora Salesiana, 1985. [ Links ]

JULIA, Dominique. A cultura escolar como objeto histórico. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v.1, n.1, p.9-43, jan./jun. 2001. [ Links ]

MELO, Victor Andrade. O espetáculo que educa o corpo: clubes atléticos na cidade de Niterói dos anos 1880. Revista História da Educação, Pelotas, v.23, p.1-34, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/85836. [ Links ]

NAGLE, Jorge. Educação e Sociedade na Primeira República. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2001. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Heloisa Helena Pimenta. A higienização dos costumes: educação escolar e saúde no projeto do Instituto de Hygiene de São Paulo. Campinas: Mercado de Letras; Fapesp, 2003. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Heloisa Helena Pimenta, Regras de bem viver para todos: a Bibliotheca Popular de Hygiene do Dr. Sebastião Barroso. Campinas: Mercado de Letras; Fapesp, 2017. [ Links ]

SILVA, José Cláudio Sooma; RIZZINI, Irma; SILVA, Maria de Lourdes. Remodelar a capital carioca e sua gente: educação e prevenção nos anos 1920. Revista História da Educação, Pelotas, v.16, p.198-224, 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S2236-34592012000200010. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. Templos de civilização: um estudo sobre a implantação dos Grupos Escolares no estado de São Paulo (1890-1910). 1997. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1997. [ Links ]

STEPHANOU, Maria. Tratar e educar: discursos médicos nas primeiras décadas do século XX. 1999. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. 1999. 2v. [ Links ]

VIÑAO FRAGO, A; ESCOLANO BENITO, A. Currículo, espaço e subjetividade: a arquitetura como programa. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2001. [ Links ]

VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. Culturas escolares: estudo sobre práticas de leitura e escrita na escola pública primária (Brasil e França, final do século XIX). Campinas: Autores Associados, 2005. [ Links ]

VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. Culturas escolares: entre la regulación y el cambio. Propuesta Educativa, n. 28, p. 28-37, 2007. DOI: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=403041700005. [ Links ]

VIOLA, Valeria. Arquitetura escolar durante o fascismo em Itália. Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v.23, e82782, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/82782. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

COLÉGIO SALESIANO SANTA ROSA. Anuário de 2003 - 2004. Niterói: Memorial Histórico do Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, 2004. [ Links ]

COLLEGIO SALESIANO SANTA ROZA. Proposta de oficialização. Niterói: Memorial Histórico do Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, 1927. [ Links ]

COLLEGIO SALESIANO SANTA ROZA. Anuário de 1915. Niterói: Memorial Histórico do Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, 1915. [ Links ]

COLLEGIO SALESIANO SANTA ROZA. Anuário de 1930. Niterói: Memorial Histórico do Colégio Salesiano Santa Rosa, 1930. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO NOSSA SENHORA AUXILIADORA. Anuário de 1914. Campinas: Lyceu Salesiano Nossa Senhora Auxiliadora, 1914. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Anuário de 1916. São Paulo: Lyceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus, 1916. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Anuário de 1918. São Paulo: Lyceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus, 1918. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Anuário de 1921. São Paulo: Lyceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus, 1921. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Anuário de 1925. São Paulo: Lyceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus, 1925. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Anuário de 1930. São Paulo: Lyceu Salesiano Sagrado Coração de Jesus, 1930. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Jogo “Estado” entre interno e externo, início 1906. 1906. 1 fotografia. Memorial do Colégio Salesiano Coração de Jesus. Pasta de fotos n. 3, Lyceu Coração de Jesus 1902 - 1907, cartelas 38 a 84. [ Links ]

LYCEU SALESIANO SAGRADO CORAÇÃO DE JESUS. Recreio no pátio do Lyceu 1908. 1908. 1 fotografia. Memorial do Colégio Salesiano Coração De Jesus. Pasta de fotos n. 3, Lyceu Coração de Jesus 1908 - 1914, cartelas 85 a 126. [ Links ]

1English version: Tikinet Edicão. The authors thank Espaço da Escrita - Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa - UNICAMP - for the language services provided..

2In 2019, the journal História da Educação published a dossier on the subject including studies by Helfenberger and Schreiber (2019), Viola (2019), Ibarra (2019), Arata (2019), and Ermel and Bencostta (2019b). The dossier addressed primary school architecture in different geographic spaces, between the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century.

Received: June 10, 2021; Accepted: September 15, 2021

texto en

texto en