Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-79

Papers

Sertões: stories and memories of the education and culture of the Sertanejo people1

1Instituto Federal de Alagoas (Brasil). jailson.costa@ifal.edu.br

2Universidade Federal de Alagoas (Brasil). naide12@hotmail.com

This paper presents researches carried out from 2011 to 2018, in the sertão of Alagoas, and were focused on literacy and culture actions, developed in the sertão community during the period of the civil-military dictatorship (1970-1985), based on Oral history, Alberti (2008) and Bosi (1994), privileging interviews and photographs as sources. These reports have as purpose to present the memorialistic narratives, about several Alagoas’ sertões, with emphasis on the education and culture of the people of the countryside. These narratives go against official history, which reinforces the stigmas about this region, led by the project of colonial domination that is perpetuated in the hegemonic discourses currents of our country even in nowadays, and constantly fights for the domination of powers and knowledge. The oral and visual sources brought new reflections in relation to the place - Alagoas’ Sertões - and made us realize that resignifications were possible, even during the military dictatorship.

Keywords: Memory; Orality; Photography

Este texto retrata pesquisas realizadas no período de 2011 a 2018, nos sertões de Alagoas, que tiveram como foco as ações de alfabetização e cultura, desenvolvidas na comunidade sertaneja no período da Ditadura civil-militar (1970-1985), apoiando-se na História oral, Alberti (2008) e Bosi (1994), privilegiando como fontes as entrevistas e fotografias. Estes escritos têm o objetivo de apresentar as narrativas memorialísticas, sobre muitos sertões alagoanos, com ênfase na educação e cultura do povo sertanejo. Essas narrativas vão na contramão da história oficial, que reforça os estigmas sobre a região sertaneja, encabeçados pelo projeto de dominação colonial que se perpetua nos discursos das correntes hegemônicas do nosso país, que lutam pela dominação dos poderes e dos saberes. As fontes orais e visuais trouxeram novas reflexões em relação ao lugar - Sertões alagoanos - e nos fizeram perceber as ressignificações que foram possíveis, mesmo em tempo de regime militar.

Palavras-chave: Memória; Oralidade; Fotografia

Este texto retrata las investigaciones realizadas durante el período de 2011 a 2018, en los sertones de Alagoas, cuyo foco fueron las acciones de alfabetización y cultura, desarrolladas en la comunidad sertaneja durante el período de la Dictadura civil-militar (1970-1985), con base en la Historia oral, Alberti (2008) y Bosi (1994), privilegiando las entrevistas y fotografías como fuente. El objetivo de estos escritos es presentar las narrativas memorialísticas, sobre muchos sertones alagoanos, con énfasis en la educación y la cultura del pueblo sertanejo. Estas narrativas se contraponen a la historia oficial, que refuerza los estigmas sobre la región sertaneja, encabezados estos por el proyecto de dominación colonial que se perpetúa en los discursos de las corrientes hegemónicas de nuestro país, en lucha por la dominación de los poderes y los saberes. Las fuentes orales y visuales trajeron nuevas reflexiones con relación al lugar - sertones alagoanos- y nos permitieron entender las resignificaciones que han sido posibles, incluso durante el régimen militar.

Palabras clave: Memoria; Oralidad; Fotografía

Initial Considerations

The reconstruction of the history of the Sertões of Alagoas, from the memories of its subjects, motivated our research through the Sertanejo community, a region that lacks the preservation of the real written memory, especially when the sources that register the facts are influenced by the political interests. In our writings, we use the term sertões, in plural, because we recognize the diversity that populates these spaces, which prevents us from using the sertão in the singular. In this "[...] space [we register our] regional identity [discovering ourselves, since] it has [our] difference, diversity, multiplicity of realities and, [...] of representations" (ALBUQUERQUE Jr., 2014, p. 41-42).

The Sertões of Alagoas, as well as the entire state of Alagoas, carry historical stigmas; nevertheless, in the countryside region these marks are even worse, since the priority, in the process of historical formation of these lands, was to serve the external market with the production of sugar cane in the mills. The less favored population had to face the periodic droughts of the Sertão.

The struggle for survival in the Sertões is strongly marked by the submission of small farmers, on lands usually borrowed from squatters, who had to struggle, in the midst of climatic conditions, for a harvest that would minimally guarantee the sustenance of a family, most of them numerous, during the whole year. The sertanejo families who ventured to leave the sertões, risking new life perspectives, encountered the obstacles of the production organization pattern, which left the popular classes dependent on the sugar mills and also on the textile industry, with the "[...] massive use of women's and children's labor." (VERÇOSA, 2006, p. 92).

The author emphasizes that this historical rancor made Alagoas reach the mid-twentieth century with a huge contingent of poor and laborious, completely dependent. In the Sertões, this dependence was linked to the presence of the coronelism, in which "[...] the colonel is the landowner who supports, protects, and helps his aggregates, demanding, in return, obedience and fidelity" (CARVALHO, 2015, p. 258).

In this context of poverty and struggle for survival, the actions of the Brazilian Literacy Movement (Mobral), although alienating and the assistentialism system, were the only opportunity for literacy to the countryside people; but it was mechanical and without the intention of politicizing the subjects, since their actions were the result of the military regime.

The narratives we present in this text are situated as strong human experiences, which in the words of Alves and Garcia (2008, p. 274), "[...] have amplitude in time and space. They are found narratives that [allowed us] a resignification, a different story from the [...] official political knowledge, which is, above all, written."

In this specific case, we deal with the knowledge of the Sertanejo people. In the research path (from 2011 to 2018) the oral history approach based on the theoretical postulates of Alberti (2008) and Bosi (1994), constituted the type of research used by us, articulating the photographs that are narrative images, becoming also sources. It is important to say that the appearance of the photographs at the time of the interviews helped us to realize the need for this interaction between the visual sources - photographs - and the oral sources - the memorial statements of the subjects who participated in the historical event.

In our study trajectory, oral history has played a fundamental role in the reconstruction of historical facts, since it has allowed us to: "[...] conduct recorded interviews with people who could testify about events, conjunctures, institutions, ways of life, or other aspects of contemporary history" (CPDOC).

In this sense, we operated with the thematic interview, which "[...] is primarily [dedicated] to the participation of the interviewee on the chosen theme" (ALBERTI, 2008, p. 175). The restitution of the past through memory, in our studies was and will always be carried out with great care. We learned, in dialog with Bosi (1994) about the impossibility of recovering the past. It is only possible to reconstruct and rethink this past, based on the ideas and images of the present. In this direction, the author points out that "Memory is an image constructed by the materials that are, now, at our disposal, in the set of representations that populate our current consciousness" (BOSI, 1994, p. 55).

We emphasize in this investigative path the importance of the interaction of oral sources with others sources - the photographs -, trying to compose a documental network, agreeing that: "In the analysis of oral history interviews one should also keep in mind other sources - primary and secondary; oral, textual, iconographic etc. - about the subject studied" (our emphasis) (ALBERTI, 2008, p. 187).

In order to present the memorial narratives, about many of the Sertões of Alagoas that we experience, with emphasis on education and culture of the countryside people, this article is composed of four items: in the first, we comment on the regulatory conceptualizations that invisibilize the Sertões and its people, constituted with great force in the course of official history. In the sequence, we present Santana do Ipanema, the starting point of our research through the Sertões; anchored in the memorialistic narratives of two sertanejo people; in the third and fourth item we lay on the memories of the sertanejo people with emphasis on literacy and on aspects of the traditional cultures of the sertanejo community.

Conceptualizations that invisibilize the Sertões and the Sertanejos

The history insistently told and presented about the sertões and the inhabitants that populate this space were/are histories marked by the hegemonic discourses that dictated and continue to dictate what it is convenient for them to say about the history of the sertanejo people. The stigma of this region comes from the colonial domination project that is perpetuated in the discourses by the hegemonic forces of our country, which constantly fight for the domination of power and knowledge, disrespecting the countless differences that characterize the various contexts of a country of continental dimensions.

The conceptions that have been propagated about the Sertões, through the stigma of a backward place where disorder and brutality reign, can no longer be the main discourse about this region. Other stories need to be elucidated in order to break the stereotypes created and cultivated about the Sertões of the Northeast. In this sense, in this text, we are going against official history in an attempt to demonstrate what has not been/is not told, seeking, above all, to deconstruct the regulatory conceptualizations constituted with great force throughout history about the Sertões and its people.

João Guimarães Rosa, in his work Grande sertão: veredas, demonstrates sensitivity when he ratifies that this region cannot be reduced to a mere place, since: "if you search for sertão you will never find it." The sertão goes beyond the spaces ideologically demarcated and stigmatized by men, thus the sertão pluralizes, ceases to be unique and reaches other proportions and suddenly and insistently "[...] when we do not expect, the sertão appears" (ROSA, 1986, p. 356). It is a space that goes beyond the stereotypes that have been attributed to it, it is a field of plurality, taking into account the diversity that permeates this region.

The discursive formulations that are propagated, both by literature and the media, present the Northeast and its sertão as a space stopped in time, and which need to be rethought, considering, above all, the sertão as a space of diversity. This vastness of the sertão appears strongly in the work of Guimarães Rosa (1986, p. 458) when the author seeks to demythologize the imaginary of the sertão as a geographically demarcated space: "The sertão accepts all names: here is the Gerais, there is the chapadão, over there is the caatinga”. The territorial infinity that Guimarães Rosa describes gives the sertão the immeasurable value that this space carries.

In his masterful work Os Sertões, published in 1906, Euclides da Cunha presents concepts he built of the Sertões and its inhabitants, images that are often ambiguous and contradictory. The author emphasizes the landscape that, at the same time that it is desolate and desert-like, is also paradisiacal, describing it as a land that goes "From extreme aridity to extreme exuberance. (CUNHA, 1954, p. 231). These contradictions appear in the author's narratives when he clarifies that, when the rains come, away from the prolonged periods of drought "The sertão is a paradise" (CUNHA, 1954, p. 43). The author presents this space in its imprecisions, especially climatic, when he says that "the sertão is a fertile valley. It is a vast orchard, with no owner".

The Pernambuco writer Josué de Castro, in his famous work Geografia da fome, in the 1940's, already denounced the social and political aggravating factors that deteriorate this space. When presenting aspects about the difficult survival condition of the "sertanejos", he clarifies: "Much more than drought, what causes hunger in the Northeast is generalized pauperism, progressive proletarianization, it is thinness, relative or absolute misery, depending on whether it rains or not in the sertão" (CASTRO, 1984, p. 260).

The author portrays, in his work, the hardship that threatened the existence of the sertanejos, making them hostages of the exclusion processes that were constantly spreading within the poor layers of Brazilian society. The writer considers the "phenomenon of hunger" to be of economic interest to a dominant minority: "A silence premeditated by the very soul of culture: it was the interests and prejudices of the moral, political and economic order of our so-called western civilization that made hunger a forbidden theme [...]" (CASTRO, 1984, p. 20).

Therefore, it is a theme that for a long time has been ignored by the rulers of this country. Given the scenarios presented to us by Rosa (1986), Castro (1984), and Cunha (1954) and the readings we have done, we assume in our research the term sertão in the plural. As noted by Xavier (2018, p. 513) we highlight the need to recognize the "[...] territory as a scale of place. Let it speak and reveal its tensions and conflicts, its shortcomings, its conformisms and its revolts, but also its riches, its values, and its possibilities".

It is important to note that in the Sertões of Alagoas we still find in its depths the relationships of “bossiness”, which means landlords still rule with an iron hand. As already denounced by Ramos (2007, p. 175): "[...] there nobody gets land easily, the salary is low - and in the gates of the despotism of the landlord you have to deprive yourself of everything". The small farmers who pursued survival, fleeing the hunger of the sertões, where the thistle - a plague of farming - destroyed the plantations, sought space to produce on borrowed land in a part of the state where the land is destined for sugarcane production in order to survive.

These historical facts ended up creating a stereotype of the sertanejo region, assigning this locality and its people a secondary, unprivileged place. In this sense, caricatures of the Sertões subjects were coined as beings worthy of pity and assistance from the powers that dominate, in a patriarchal and colonialist way, those judged by them as "incapable". The rupture of this stigmatized vision becomes a huge challenge, and the struggle to overcome a unified history must take place, in the perspective of breaking the invisibility built by the excluding historical process that was unable to perceive the differences and is present in the reality we are living in Brazil, starting January 2019.

We affirm this, considering that the stigmas that have been circulating about the Northeast, the Sertões, and the countryside are perpetuated in the images of these localities and the people who inhabit them. These are perspectives that seem to have been dormant and unbroken. We have discovered in our research that these people have a lot to tell in their stories. Stories of experiences that are not linear, stories of experiences that are re-signified in everyday life, therefore, they cannot be taken as one-way stories.

We focus on emphasizing Boaventura de Sousa Santos who very aptly criticizes the project of domination and clarifies that, in this system of distinctions, differences are established through radical lines that

'divide social reality into two distinct universes: the universe 'on this side of the line' and the universe 'on the other side of the line'. The division is such that 'the other side of the line' disappears and as reality becomes non-existent, and is produced as non-existent (SANTOS, 2010, p. 23).

In this perspective, there is only room for what is "on this side of the line", in other words, what is presented by a hegemonic force that dominates knowledge with power. What is "on the other side of the line" is considered invalid, disrespected, disregarded - invisible. Thus: "On the other side of the line, there is no real knowledge; there are beliefs, opinions, magic, idolatry, intuitive or subjective understandings, which, at best, can become objects or raw material for scientific inquiry" (SANTOS, 2010, p. 25).

The author argues that popular knowledge is disregarded in the name of scientific knowledge. The knowledge that comes from the layers that are outside the hegemonic mainstream cannot be propagated, it must be denied, since it deconstructs what was historically established as truth. Santos, (2010, p. 31) states how evil this distinction is when he denounces that: "The negation of one part of humanity is sacrificial insofar as it constitutes the condition for the other part of humanity to assert itself as universal." One can see that the annulment of the other is the central point for the self-affirmation of those who dominate the powers and knowledge, making this practice historically naturalized.

We observe that the Sertões and the Sertanejo people are on the other side of the line. They are hostages of a historical stigma told and retold with such eloquence that, for the majority, it has become naturalized as truth. In these truths, the specificities of the Sertões region and its inhabitants have been succumbed.

In this sense, it is possible to observe the hides existing in the homogeneous history, emphasizing the historical debt tied to the history told by the winners that, in turn, ends up disregarding the peculiarities of those who did not have, in the telling of history, their value.

It is important to highlight the Sertão as a heterogeneous space that has its own life. This heterogeneity needs to be respected, especially regarding the fact that the sertão is a space in constant change. It is necessary to understand the contemporary experiences of this space, which has not remained stagnant in the past, but is daily reinvented.

The starting point context - Santana do Ipanema

The epistemological curiosity to investigate the mobilization of the Sertanejo community around the actions of Mobral (1970-1985) came from previous researches, due to the recurrence of quotes from this movement, which led us to the city of Santana do Ipanema, located in the middle Sertão of Alagoas.

The territory of the middle Sertão of Alagoas is configured as a space of plurality, because it is composed of nine municipalities that have their peculiarities, despite being so close geographically. Among these Sertões that are part of the middle sertão of Alagoas, the emphasis goes to the municipality of Santana do Ipanema, which was characterized as a starting point for these and other investigations.

The first landmark in the history of Santana do Ipanema is registered in the XVIII century, a time when the city was reduced to a village inhabited by Indians and mestizos. Melo, F. and Melo, D. (1976), in their reports, explained that before the creation of the District of Alagoas there was the concession of some allotments in the region, and one of them was located where the city of Santana do Ipanema is nowadays. In this context, “the farms appeared, close to each other so that they could communicate with themselves, and also with the riverside villages of the valuable and traditional São Francisco River" (MELO, F.; MELO, D., 1976, p. 19-20).

It is a city located in the Sertões of Alagoas that started its development in a rural way, with the name Ribeiro do Panema. In 1771, it was renamed Santa Ana da Ribeira do Panema, due to the construction of a chapel in honor of Saint Ana.

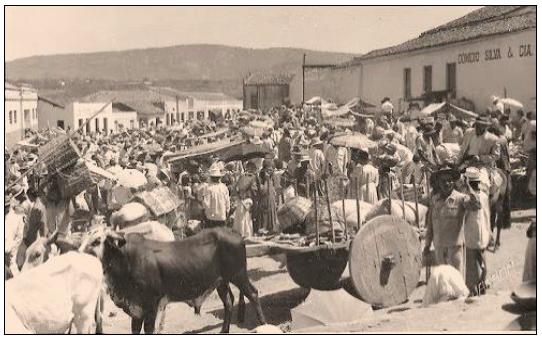

In the late 1920s, an economic aspect that gained prominence in the town was the open market, on Saturdays. It became, then, an important support for the region's economy. The movement was intense, as shown in figure 1 below, due to the "[...] arrival of numerous oxcarts and traders, not to mention other people who came to the place to buy their foodstuffs, their chitas (traditional portuguese cotton fabrics), their alpercatas or to deal with the authorities. (MELO, F.; MELO, D., 1976, p. 8).

Source: Available at: http://www.maltanet.com.br/galeriadefotos/foto.php?id=754.

Figure 1 Santana do Ipanema on an open market day. Image: Mr. Sulino Collection: Erinha.

The photograph in the figure above is "[...] a mirror of past moments" (LEITE, 1993, p. 160) and show to us the people that crowded to celebrate the culture of gathering weekly to practice this democratic cultural act, in a public space full of diversity, although the shining sun of the Sertões. This space is strongly marked "[...] by the multiplicity of voices, speeches, and sayings that mix, confuse themselves, and end up generating a real gibberish of voices.

The figure also refers to the "[...] multiplicity of appeals around the distinct merchandises in order to sell" (ALBUQUERQUE JR., 2013, p. 24). A place of popular convergence, in which the products produced in the urban and rural communities of the Sertões are traded, making the city a meeting point of diverse cultures.

Barros (2010, p. 76), in a memorialistic text, describes how the Santana do Ipanema open market used to happen. It occupied an extensive physical space and took place on Saturdays, when people climbed the hillsides. The author explains that there were

people walking in all directions, crowded stores, blind people singing while swinging the ganzá, arriving trucks, ox carts, carts with women dressed in powder-coats and many horsemen. Saying good afternoon to all the people leaning out of the windows, many women dressed in long skirts and big heads passed by. They were the matutas with white or totally black cloth on their heads. They came to do the fair arriving from the outskirts of Santana, from the small properties in the neighborhood.

The population growth of the town was very much related to the cangaço2 in the region. Families living at the time in the rural area, faced with the constant attacks of Lampião3, decided to migrate to Santana do Ipanema. According to Rocha (2014), around 1925 appeared in the Santana community three emblematic figures that marked the imagination of many Sertanejo, supported in the caste of heroes: "the 'colonel' Delmiro Gouveia, who had controlled the Paulo Afonso waterfall; the 'captain' Lampião, who wandered constantly victorious in the caatingas of Alagoas; and Lieutenant José Lucena, who competed with him on behalf of the government [. ...]" (ROCHA, 2014, p. 19).

With the population growth, the city presented the need for expansion of public agencies, such as: schools and health centers for the care of people who arrived at the municipality. In the educational field, the mayor Joaquim Ferreira da Silva got state funds for the construction of a school that he named Padre Francisco José de Albuquerque and also "He made the teaching staff come [from the capital] to educate the child population. It was a partial solution to this case." (MELO F.; MELO, D., 1976, p. 63).

In the early 1970s, in the middle of the civil-military dictatorship, a new manager took over the municipal government of Santana do Ipanema. According to the authors, the period of his administration was one of difficulties, since a great drought occurred, which caused a terrible economic and social crisis in the town. As a consequence, there was hunger and thirst, with more intensity among the rural population, and diseases decimated herds of cattle. According to Melo, F. and Melo, D. (1976), despite this situation, the mayor managed to build an elementary school in an agreement signed with the Secretariat of Education of Alagoas and, in that decade, supported the implementation of one of the Mobral Programs, called Functional Literacy Program (Programa de Alfabetização Funcional - PAF), to assist illiterate adults during the nighttime.

Memorial narratives of Sertanejos’ literacy process

Following the guidelines of oral history, we left the municipality of Santana do Ipanema in search of other Sertões, where it was possible to make contact with people who had stories and memories of education and culture of the Sertanejo people, based on their memorial narratives from oral and visual sources. In this context, we highlight the contribution of two people who experienced the actions of Mobral - especially the PAF, developed in the Sertões of Alagoas. Both were direct participants, with differentiated participations. They were a former student and a former area supervisor of the program.

The PAF/Mobral was a program that, since its nomination in 1967, had two perspectives. The first functional perspective was a way of literacy, which had the purpose of using it for immediate application in daily life of the students, it also should be done in a short period of time, quickly reverting the condition of the labor force from illiterate to a minimally literate one.

The second perspective brought the concept of functionality, dedicated to literacy, came from international formulations and agreements of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), in a political strategy to reverse the alarming picture of illiteracy in the world, by the logic of capital, demonstrating the ambiguity of the agency's actions. By this logic, literate workers were more productive and wasted fewer resources in all the activities performed.

Despite the strong motivation of the population for the activities of Mobral, it was far from the multiple experiences of popular education initiated and developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, based on Freire, which assumed an emancipating role for the poor population and of the popular classes, especially in the Northeast of the country. These experiences, however, were aborted by the civil-military dictatorship.

The project of the military dictatorship was to help the capitalist advance in the country's constitution through industrialization and, for this reason, it needed qualified labor - which included more schooling and reduction of illiteracy among the industrial workforce - in order to attract multinationals and to be able to "get Brazil out of the historical backwardness". This project also included improving the levels of schooling of young people and adults, who had been historically denied the right to education in the country. The first path, undeniably, was learning to read and write in order to consider them no longer illiterate, so men and women could meet the requirements of capital and the labor force. Literacy was presented as a quick possibility, because the dictatorship was in a hurry to execute its project of building a "big Brazil".

For the repressive government of that historical moment, adult literacy made sense because the development of the country, with the entry of multinationals, required a labor force capable of mastering, at least, basic reading and writing techniques, so they could comply with international dictates regarding the reduction of illiteracy among workers, which was solved with short literacy proposals.

At the time, there were many implications between the rural and the urban. These implications were both psychosocial and affective, as well as politico-ideological, since this displacement proposal, in our understanding, must have contributed to lower self-esteem and also to increase the feeling of impotence in face of the difficulties of displacement of those rural sertanejos, who were being provoked to become literate, which had never happened in the region.

The initiative of implanting literacy classes in the farms and ranches, even in precarious situations, was very important for the attendance of many rural workers, who after their daily work, still found the strength to attend the classes, which, according to one of the former literacy students, took place in spaces, many times, such as the flour house, illuminated by the light of a

Candlestick or lantern. When the gas of the lantern ran out, we had to use the lamp. They put the lamp close to the blackboard and then we could see the letters. We never studied in a school, it was in the houses, then we went to a bodega that had a big room. It was very difficult, that's why many people gave up (FERNANDO, 69 years old).

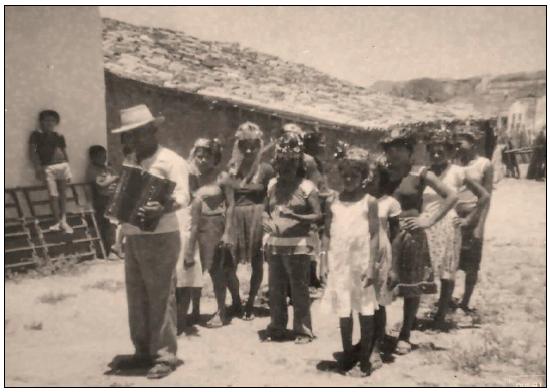

The next photograph shows a group of literacy students from the Functional Literacy Program (PAF) in the municipality of Palestina, also located in the sertão of Alagoas, near Santana do Ipanema, according to the testimony of the former supervisor of the region. The photo is a record of one of the cultural presentations by the PAF students and shows how the integration between the Cultural and Literacy Programs worked. According to the narrator, the photograph captured the moment when the group was organizing to perform the reisado, one of the most traditional cultural manifestations in Alagoas.

Source: Personal archive of Hélio da Silva Fialho - Mobral's former area supervisor.

Figure 2 Cultural activity with the PAF students.

This photo allowed the analysis of an instant in which the group, composed mostly by women, was getting ready to present themselves to the public, and had the help of a musician, also a literacy student from the PAF, who brought an eight-bass accordion to please the people. This instrument, according to the narrator, belonged to the Mobral Cultural Center, which always made it available for presentations in nearby areas. The physical space represented in the image reminds us of the simplicity of the rural communities of the Sertões, in a context where many mud houses decorated the streets of the small villages.

These memories and others, which we evoked in this research, from subjects forgotten by official history - living witnesses - brought new reflections about Mobral, especially in relation to the place, the Sertões. We saw narratives different from the ones that populate the national imaginary about this program. This made us realize the multiple meanings that can be built in Brazil in the practices developed by a program with the dimension that Mobral had.

These studies had their relevance in the need to reconstruct the actions of the Functional Literacy Program and the Cultural Mobral Program based on the stories and memories of the people from the Sertões of Alagoas, about how they experienced and gave new meaning to the actions developed by Mobral during the civil-military dictatorship. Re-signification understood in this research as "ways of doing" that, in the words of De Certeau (2011, p. 41), "[...] constitute the several practices that the users reappropriate the space organized by the techniques of sociocultural production", or, in other words, the meanings attributed in their own cultures to the actions presented by the Mobral Cultural Program in the Sertão community.

The cultural practice of the Batalhão de Lagoa

In our research through the sertões we were able to gather, in addition to the oral narratives, a documentary corpus of 87 photographs characterized by various photographic behaviors, mostly by unknown professionals, among which emerged the possibility of reconstructing the history of the Batalhão de Lagoa.

Based on the orality and photographic records dating from the early 1980s, we opened a space to comment on the experience of a group of people belonging to the Sertão community of Santiago, located nearby the municipality of Pão de Açúcar - Alagoas’ Sertão.

In its organization, the Batalhão de Lagoa has room for the opening of cooperation among the members of the participating communities. They help each other in the daily work, as well as share the popular festivities that resist the colonizing standardizations, with the popular manifestations that are still recurrent in the most traditional communities in the Sertão of Alagoas.

Thompson (1998) gives support to confirm this resistance of the traditional communities that, even though few in numbers, still preserve their culture and traditions. The researcher clarifies that these fields of resistance are punctual and, generally, are evidenced in communities of small farmers and fishermen, in which the rhythm of work is still dictated by nature and not by market time; the logic that prevails in these contexts is the need to perform daily tasks, mentioned in the quote below, which the author calls "natural" rhythms of work:

taking care of sheep at the time of calving and protecting them from predators; milking cows; taking care of the fire and not let it spread to the peatlands (and those who burn coal must sleep beside it); when iron is being made, the furnaces cannot go out (THOMPSON, 1998, p. 271).

Despite the duty of those tasks, the subjects of the popular classes have not yet surrendered to the time of capital, that is, to the time of the clock, which makes them peculiar and, above all, resistant to the commands of capitalism in their rural occupations.

The task-forces(multirão) or Batalhão are understood as a form of cultural creation of the people. Carlos Rodrigues Brandão (1995, p. 209) when describing the characteristics of a Mutirão clarifies that this collective task contains the elements of:

giving, receiving, giving back. There is an invitation governed by the need for a collective work, associated with the desire to accomplish it not through a paid company, but through a collectivization of a service experienced in one day, as a rite. There is an obligatory response to the invitation, for reasons of kinship, neighborhood, friendship, associated or not with a previous and equivalent debt on the part of an invitee (the invitee has previously participated in a Mutirão on his land).

The element of giving, of collectivity, of companionship, ends up softening the physical tiredness of manual labor. Our narrator, a former area supervisor in this Sertão region, narrated the experience and the tradition of the Sertão:

A group of local residents who worked in the rice plantation, on whose land in Lagoa do Santiago the rice was planted in sharecropping, that is, of the amount of rice that was harvested, 50% went to the land owner and the other 50% stayed with the plantation owner. Each day, depending on the area of land to be planted and replanted, the same group (Batalhão da Lagoa) would leave the plantation owner's house (villager) to 'close the land' of a certain person (villager), where the group would spend the whole day working and singing traditional local folk songs. (HÉLIO FIALHO - FORMER MOBRAL AREA SUPERVISOR).

The culture, traditions, and rituals are also narrated by the interlocutor, who tells with enthusiasm and pride having lived with these subjects the cultural experiences of a peculiar context in the history of these workers, and very moved he continues:

Usually the group would leave the 'owner's' house to the area of land to be planted in the lagoon. The owner of the plantation would carry a white flag raised on a pole. Upon arriving at the desired location (the area of land to be planted in the lagoon), the group members would enter the lagoon waters and the white flag would be planted at the margin (on the land). To get through the long and arduous day's work under the scorching sun, the group would sing continuously - some would sing a few verses and others would answer. And so they spent the whole day working. At dusk, the group returned the same way it had walked in the morning. Upon arriving at the house of the 'midwife of the day', the members began to dance a kind of 'coco de roda' or 'pagode de coco'. During and after the closing of the land (until returning home), the members of the group (women and men) drank wine, cachaça and ate rubacão with stewed meat (cattle or poultry). And so, the traditional lake groups, very common in the riverside localities that lived from rice plantations), resisted time, but did not resist the disappearance of the lakes of the Velho Chico. (HÉLIO FIALHO - FORMER SUPERVISOR OF THE MOBRAL AREA).

The rituals mentioned in the narratives of the interlocutor leave room for us to infer about the various possibilities of interpretation of the experiences and traditions of the sertanejos. Brandão (2002) when emphasizing the popular knowledge present in the culture of each community emphasizes that:

Within the culture of the people there is a knowledge; their history makes this knowledge alive and continually transmitted between people, becoming an education (our emphasis). It is from these connections of popular culture work that the popular educator must situate their work through culture. They have no right to invade these domains of education and knowledge of the people's culture. (BRANDÃO, 2002, p. 97).

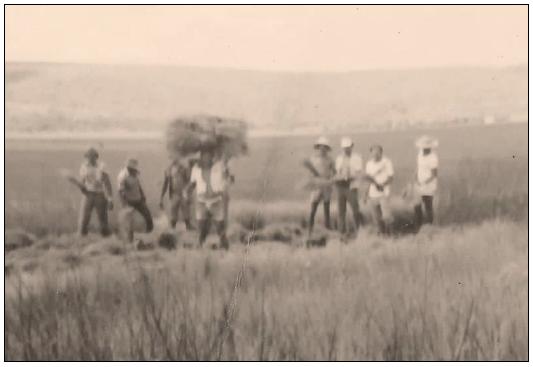

The word education refers in its broad sense to the everyday social relations established within communities. In other words, the knowledge impregnated in the culture of the people of the rural communities of the sertões. The following image shows those groups' work rhythm, orchestrated by the singing and the collective effort of the peasants who, in the name of tradition, anchored in solidary coexistence, develop productive and, above all, cooperative work.

Source: Personal archive of Hélio da Silva Fialho - Mobral's former area supervisor.

Figure 3 Batalhão de Lagoa - Povoado Santiago, August 1981.

The photograph, which, for Guran (2011, p. 80) "[...] is by nature eminently descriptive," records the daily work of the sertanejos, some of them former students of the PAF/Mobral, who aggregated to do a certain part of the work proposed for that period of the day, better known as the serviço de eito. The determination of the workers to do the eito demonstrates that the ritual of those groups was also controlled by the exercise of competition and often conflict among the laborers (BRANDÃO, 1995).

The construction of the Xingó Hydroelectric made the formation of the lagoons reduced, which put an end to the culture of rice production in Sertanejo lands. The disappearance of the lagoons represented, for the riverside communities, the end of the production of a cereal considered to be the main ingredient in the diet of the sertanejos, and that added to beans makes the diet balanced, providing energy for the fulfillment of the arduous manual labor daily tasks.

It is important to point out that rice cultivation in Mutirão, taking advantage of the flooding of the lagoons, certainly existed long before the Mobral. This cultural practice started to be supported by Mobral, on a propitious occasion, and hence was considered by the Commission of the Municipality of Pão de Açúcar as one of the most significant cultural practices. We understand that in this case there was an appropriation by Mobral of a form of action typical of the local culture.

Final considerations

As a "conclusion", we emphasize that the "answers" built during our studies were originated, above all, from an exercise of listening to ordinary people who, generally, do not appear in the official written records, but who are subjects that helped in the recreation of the history of Mobral, as recommended by Walter Benjamin: "against the grain".

We believe that to study the Sertões is a way of breaking the regulatory paradigms that conceptualize it. This deconstruction implies, above all, the breaking of the stereotypes attributed to the Sertões subjects, historically constituted as rude subjects, stagnated in a past far away from the contemporary world. It is important, therefore, to continue our research through the Sertões, deconstructing the conceptions that regulate and annul the knowledge of the Sertanejo people.

Besides the oral narratives, the photographs used as a source - with non-verbal messages - allowed the dynamics of the memory of the interviewed subjects and, also, helped to sharpen our analysis. We hope that they will help readers interested in this work to decipher the meaning and cultural content of the images taken as historical documentation, to recover the construction ignored in the official history.

In the process of this research, it became explicit that the Sertanejo people in this study let themselves be invaded by what they could not control, but resisted with the popular wisdom, showing what they knew to do. This was part of the "tricks" of popular resistance to the services offered by Mobral. What this does not mean is that the community's involvement in the cultural and literacy actions represented the acceptance/passivity of the actions presented, because when these actions were implemented, certainly there was already a social structure of popular culture based on the habits and traditions of the people from the Sertões. Examples of this reality are the workers of the Batalhão de Lagoa that appear in Figure 3, with their rites, which existed long before Mobral.

The strong ideological charge that surrounded the national imaginary did not prevent the Sertanejos from acting as cultural practitioners, re-signifying the actions with their "ways of doing", based on the "uses" they made of them in their "space" - the sertão of Alagoas -, creating possibilities of new interpretations and appropriations of the actions developed.

We register that, even in situations conceived with diverse and previously defined purposes, aiming at the social control of the populations, the investigated reality imposed itself beyond political strategies. From the real conditions emerged unforeseen daily "tactics" that invented new logics of appropriation of what was offered to the subjects, which escaped control, and may result in new forms of meaning.

In the Sertão of Alagoas, many reflections still remain open, making itself, therefore, as a fertile field for research in Alagoas, as we have already evidenced, due to the absence of written memory. This awakening generates possibilities of continuity for this study and, also, for other researchers interested in reconstructing history through the eyes of the "ordinary people" forgotten by history. These people keep in their memories significant experiences that deserve to be triggered in the present moment, with the purpose of valorization and preservation of memory and, consequently, modifying monolithic visions of the stories that are commonly told about the Sertões.

REFERENCES

ALBERTI, Verena. Histórias dentro da história. In: PINSKY, Carla B. (Org.). Fontes históricas. São Paulo: Contexto, 2008, p. 155-202. [ Links ]

ALBUQUERQUE JR., Durval Muniz de. A feira dos mitos: a fabricação do folclore e da cultura popular (Nordeste 1920-1950). São Paulo: Intermeios, 2013. [ Links ]

ALBUQUERQUE JR., Durval Muniz de. Distante e/ou do instante: “sertões contemporâneos”, as antinomias de um enunciado. In: FREIRE, Alberto (Org.) Culturas dos sertões. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2014. [ Links ]

ALVES, Nilda; GARCIA, Regina Leite. Prefácio - Continuando a conversa. In: FERRAÇO, Carlos Eduardo; PEREZ, Carmem Lúcia Vidal; OLIVEIRA, Inês Barbosa de Oliveira (Org.). Aprendizagens cotidianas com pesquisa - novas reflexões em pesquisa nos/dos/com os cotidianos das escolas. Petrópolis: DP et Alii, 2008. [ Links ]

BARROS, Luitgard de Oliveira Cavalcanti. Santana do Ipanema pelos caminhos da memória. In: MELO, José Marques de; GAIA, Rossana. (Orgs.). Sertão Glocal: um mar de ideias brota às margens do Ipanema. Maceió EDUFAL, 2010. [ Links ]

BARROS, Luitgard de Oliveira Cavalcanti. Pelos sertões do Nordeste. Maceió: Eduneal: Impressora Oficial, 2015. [ Links ]

BRANDÃO, Carlos Rodrigues. A partilha da vida. São Paulo: Geic/Cabral Editora, 1995. [ Links ]

BOSI, Ecléa. Memória e sociedade: lembranças de velhos. 3. ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1994. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Cícero Péricles de. Formação histórica de Alagoas. 3.ed. Maceió: EDUFAL, 2015. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Josué de. Geografia da fome: o dilema brasileiro: pão e aço. 10 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Antares, 1984. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Euclides da. Os sertões. 23.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves, 1954. [ Links ]

DE CERTEAU, Michel. A invenção do cotidiano: 1 Artes de fazer. 17. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2011. [ Links ]

GURAN, Milton. Considerações sobre a constituição e a utilização de um corpus fotográfico na pesquisa antropológica. Discursos fotográficos, Londrina, v.7, n.10, p.77-106, jan./jun. 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5433/1984-7939.2011v7n10p77. [ Links ]

JANNUZZI, Gilberta Martino. Confronto pedagógico: Paulo Freire e Mobral. São Paulo: Cortez, Autores Associados, 1987. [ Links ]

LEITE, Miriam Moreira. Retratos de família. São Paulo: Edusp, 1993. [ Links ]

MELO, Floro de Araújo; MELO, Darci de Araújo. Santana do Ipanema conta a sua história. Rio de Janeiro: Borsoi, 1976. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Graciliano. Viventes das Alagoas. 19. Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2007. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Tadeu. Modernismo & Regionalismo. 3. ed. Maceió: EDUFAL, 2014. (Coleção Nordestina; v. 85). [ Links ]

ROSA, João Guimarães. Grande sertão: veredas. 20. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1986. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Para além do pensamento abissal: das linhas globais a uma ecologia de saberes. In: SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa & MENESES, Maria Paula. Epistemologias do Sul. São Paulo: Cortez, 2010. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, Edward Palmer. Costumes em comum: estudos sobre a cultura popular tradicional. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

VERÇOSA, Elcio de Gusmão. Cultura e educação nas Alagoas: histórias, histórias. 4. ed. Maceió: EDUFAL, 2006. [ Links ]

XAVIER, Marcos. Lugar, Pluralidade da Existência e Democracia. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos Regionais, São Paulo, v.20, n.3, p.506-521, Set-Dez. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2018v20n3p506. [ Links ]

2Characterized as a revolutionary struggle against the abuses of the oligarchies, the men of the group wandered through the cities in search of justice and revenge for the lack of jobs, food, and citizenship, the causes of the disordered routine of the peasants. The term cangaço comes from the word canga - a piece of wood used to fasten oxen to an ox cart or plow.

Received: August 12, 2021; Accepted: November 10, 2021

text in

text in