Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-84

Papers

Between education, health and religion: Antônio de Almeida Lustosa and the educational care for the health of children and families in Pará (1935)1

1Federal University of Pará (Brazil). malu_callou19@hotmail.com

2Federal University of Pará (Brazil). laura_alves@uol.com.br

We analyze educational practices aimed at caring for children and the family, book used in the official schools of Belém entitled "Pastoral care for the physical and spiritual health of our inland diocesans" - 1935, written by the Salesian and Archbishop of Belém Dom Antônio Lustosa. Based on the documentary source and the understanding of the document as a raw material in the history of education, based on the cultural history of Roger Chartier, we problematize this work the dissemination of hygiene as an element of the educational process in the school, an instrument of moral and Christian morality in the city capital and inland, constituting in the family the culture of assuming a coherent and rational position in the care of the child in the historical context of the 30s, articulating science, health, religion as school knowledge.

Keywords: History of education; Education and Health; Salesian Congregation

Este artigo situa-se no campo da história da educação, onde analisamos as práticas educativas voltadas aos cuidados da criança e da família, apresentadas no livro utilizado nas escolas oficiais de Belém com título de “Pastoral em prol da saúde corporal e espiritual dos nossos diocesanos do interior” - 1935, escrito pelo Salesiano e Arcebispo de Belém Dom Antônio Lustosa. A partir da referida fonte documental e do entendimento de documento enquanto matéria prima da história da educação, pautados na história cultural de Roger Chartier, problematizamos neste trabalho sobre a disseminação da higiene como elemento do processo educativo no espaço escolar, instrumento dos bons costumes morais e cristãos, na capital e interior, constituindo na família, a cultura de assumir uma posição coerente e racional nos cuidados com a criança no contexto histórico dos anos 35, articulando ciência, saúde, religião como saberes escolares.

Palavras-chave: História da educação; Educação e Saúde; Congregação Salesiana

Este artículo se ubica en el campo de la historia de la educación, donde analizamos las prácticas educativas orientadas al cuidado de los niños y la familia, presentadas en el libro utilizado en las escuelas oficiales de Belém con el título “Pastoral para la salud corporal y espiritual de nuestros diocesanos. del campo”- 1935, escrito por el salesiano y arzobispo de Belém Dom Antônio Lustosa. A partir de la referida fuente documental y la comprensión del documento como materia prima en la historia de la educación, a partir de la historia cultural de Roger Chartier, problematizamos en este trabajo sobre la difusión de la higiene como elemento del proceso educativo en el espacio escolar, instrumento de buena moral y los cristianos, en la capital y el interior, constituyendo en la familia, la cultura de asumir una posición coherente y racional en la puericultura en el contexto histórico de la década del 35, articulando Ciencia, salud, religión como conocimiento escolar.

Palabras-clave: Historia de la educación; Educación y Salud; Congregación Salesiana

Introduction

In this article we analyze the educational practices related to the care of the child and the family, presented in the book used in the official schools of Belém entitled "Pastoral care for the physical and spiritual health of our inland diocesans" - 1935, written by the Salesian and Archbishop of Belém Dom Antônio Lustosa. Based on that documental source and on the understanding of document as a raw material of the history of education, based on Roger Chartier's cultural history, we problematize in this paper the dissemination of hygiene as an element of the educational process in the school space, an instrument of good morality and Christian manners, in the city capital and inland, constituting in the family, the culture of assuming a coherent and rational position in the care of the child in the historical context of the 35s, articulating science, health, religion as school knowledge.

It is curious to identify in that book representations and practices of the relationship between religion, health, science and education in the development of school knowledge in the 35s of the 20th century, enlightening us how and what place each of these fields occupied in the life of the population of Pará. It is interesting the relevance that health represents both for the State (the institution responsible for providing health and education to the population), and for the priest (a Salesian who takes with him in the 1930s not only the responsibility for the soul of each devotee, but for their physical and spiritual well-being).

This double concern of Father Lustosa can be explained by the Salesian sign that he carries, since his congregation has its origin in the precepts of Don Bosco, which prescribe the importance of physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being for divine and religious Christian communion, as well as for the exercise of the rules of good living in society, in a humanizing perspective.

Another issue that the source invites us to think about in this paper is the place that health occupied in the expansion and exercise of the Christian religion, as well as its importance for education in the 1935s, especially in the city of Belém, Pará.

Thus, our documental source allows us to say that it is a thought out reading from a specific historical context in the Pará´s Amazon, aimed to popular education and understood as a practice and social accomplishment for various purposes.

1. Antônio de Almeida Lustosa and the educational health care of Pará´s child and family (1935).

The history of children in the Amazon pervades and intersects with a history of religious congregations in Brazil, as these have been in the arms of Religious Congregations since Colonial Brazil, however, this relationship occurs in different ways, as they develop their social and educational projects. Each congregation has specific cultural practices, educational thinking, target audience, and work philosophies in their projects. For Bittencourt (2017), as of the Brazilian Republic, there was a strong immigration of Religious Congregations from various parts of the world, such as Italy and France, among other countries.

Immigration did not happen only according to the policies of liberal states, because the Church projected its expansion in the region colonized by Catholic countries - Portugal and Spain. Strategies began to be put into practice as early as 1858, with the foundation of the Pontifical Latin American Pious College in Rome, an institution created with the objective of forming priests for Latin-speaking countries, within the Roman canons (Fernández, 2000). However, the high point of the onslaught was the summoning by Leo XIII of all bishops and archbishops for the First Plenary Council of Latin America, celebrated in the papacy's headquarters, in the twilight of the 19th century - 1899- 1904. From this conclave emanated the guidelines for the Church´s action (BITTENCOURT, 2017, p. 38-39).

At this Latin American meeting, 53 prelates were present, among them 4 former Brazilian students of the Latin Pius College: D. Jeronimo Thomé da Silva, archbishop of Salvador and Primate of Brazil; D. Joaquim Arcoverde de Albuquerque Cavalcante, archbishop of Rio de Janeiro; D. Eduardo Duarte Silva, bishop of Goiás; and D. Francisco do Rego Maia, bishop of Petrópolis (Palomera, 2000; Souza, 2000, apud Bittencout, 2017). It is worth noting that Dom Francisco do Rego Maia was appointed Bishop of Belém do Pará by Pope Leo XIII, on June 5, 1901. He took office on March 25, 1902. He remained in Belém do Pará for four years. During his government, the following congregations arrived in Pará: Dominican Sisters, Marist Brothers, Barnabite Priests, Sisters of St. Catherine. He also approved the foundation of the Congregation of the Capuchin Regular Third Sisters.

Thus, it no longer made sense to dispute power with the State, but to align with a greater purpose, performing its actions aiming not only to constitute the good citizen, but also making him know and practice the religious teachings of a good Christian. Therefore, it is common when studying the implementation projects of the Catholic congregations in Pará - Republic, and realize that the actions of the Church are being articulated with the construction of the Liberal State. In fact, it is the liberal logic appropriating itself in the practices of reorganization and implementation of the Catholic Church. Thus, Dom Antônio Lustosa performs his actions aligned with the government of Magalhães Barata in Pará. Below in image 1: we have in the center of the photo, Dom Antônio Lustosa seated next to the Interventor, Magalhães Barata, in a visit to Bujaru-Pa.

Source: Archive of the Academia Paraense de Letras.

Image 1: Antonio Lustosa next to Magalhães Barata during a visit to Bujaru-PA

Dom Antônio de Almeida Lustosa was born on February 11, 1886, in the city of S. João del Rei - MG, he was ordained a priest in 1912. He was named bishop of Uberaba in 1925, remaining in office until 1928, and also held the bishopric of Corumbá (1928-1931), later being promoted to archbishop of Belém, Pará, by Pope Pius XI, on July 10, 1931. About the presence of Antônio de Almeida Lustosa in Pará, we know that this Salesian worked hard in a mission of romanization as archbishop between 1931-1941, reorganizing strategies with the objective of demarcating the space of the Catholic Church and Salesian presence in the north of Brazil. He was a notable religious intellectual, wrote books, occupied a seat in the “Academia Paraense de Letras” (1937), besides being a priest, he was a great writer.

Among the many achievements of Dom Antonio Lustosa - known as the Bishop of Social Justice, in Pará, the following stand out: the reopening of the Seminary “Nossa Senhora da Conceição”, entrusted to the administration of the Salesians; the creation of several congregations; the installation of religious communities of the Cruzio Priests, the Sisters Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent of Paul, the Capuchin Sisters, the Angelicas of St. Paul and the Sisters of Our Lady of the Annunciation; He also carried out the Sagration of the Basilica of Nazareth foundation of Catholic Action, participated in the restoration and uprising of the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, becoming co- founder, campaigned for good reading, the recitation of the rosary and sought to value the sacrifice of the Mass (“A VOZ DE NAZARE” NEWSPAPER, 2015, p. 5). In image 2, D. Lustosa on the left with some personalities from Pará and members of the Academia Paraense de Letras, demonstrating his value in literate culture and his participation in the vehicles of information and production of Literature from Pará.

Source: Archive of the Academia Paraense de Letras.

Image 2: On 18/08/1953 with personalities from Pará and some members of the Academia Paraense de Letras.

The Church, personified in several religious congregations and important ecclesiastical intellectual characters, made use of several resources to propagate the Christian religion, among them we have the press, engaging in the foundation of Catholic newspapers and in the realization of partnerships, religious and educational books, radio stations, as well as the creation of printed bulletins and pastoral letters that reached wide circulation quickly in the capital and inland. Besides this, we notice in the 20th century, the organization of a large Catholic network composed of several congregations, many of foreign origin, involved in the work with poor, orphaned and abandoned children, with the elderly, in hospitals, schools and associations. When studying these religious congregations, besides knowing the obvious, the project of romanization of the faithful, is it interesting to analyze how the philosophy of these institutions is articulated with the social problems faced by the population that one wants to romanize? What discourses and practices permeate the need for the installation of these congregations? What strategies do they use to involve parish priests and gain a positive presence in their prelates? What alliances are formed for the implementation of the religious work? What intellectual figures are involved in these processes and what ideologies surround them?

The historian José Maia Bezerra Neto affirms that Dom Lustosa made a great literary contribution to the historiography, not only of the Catholic Church in Brazil, but also of Amazon, with the registering of his writings during his pastoral visits to the interior of Pará. It is worth remembering that it was thanks to the efforts of D. Lustosa that the Congregation of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians (FMA) was installed in Belém on december 17, 1934. At the request of Bishop Antonio de Almeida Lustosa, the Salesian province of Turin, Italy, requested that the Congregation could send Salesian Sisters to found a missionary work in Belém do Pará. After all, our capital still did not have any Salesian work, being in the in the archbishop´s eyes, besides being necessary, a work of great social and religious return to the people of Pará. According to Azzi (2002), initially the referred work would be a boarding school and a festive oratory. Mendes (2006) when studying religious conflicts and political relations in Pará (1930 - 1941), in his master's dissertation, concluded that the effort of D. Lustosa in disseminating the Catholic presence in Pará and in the inland was linked to a larger project, that is, the Romanization.

Something important to note is that it was in the name of better religious assistance that Lustosa put into practice (and, therefore, also had facilities) the romanization in the Amazon. Following the orientation of Dom Macedo Costa, who with the collective pastoral of 1890 and an official document intended for the other parish priests and bishops of the country, called "Points of Reform of the Church of Brazil", recommended the Romanizing practice and the pastoral visits as a way to keep the population - in its entirety, given the size of the visits - close to the ecclesiastical institution. This practice was close to his intention of acting in the political field: to get more space in the public arena. To this end, the good image of the regime and of the Catholic Church in Pará was necessary for the government to run smoothly. (MENDES, 2006, p. 141).

Dom Macedo Costa was a great inspiration to D. Lustosa, who even wrote a biography of him, narrating his great deeds in the Amazon, being much admired by him, perhaps because of this, so committed to his Catholic mission. Mendes (2006) states that Dom Antônio de Almeida Lustosa took office as Archbishop of Belém in December 1931. Through the Catholic Newspaper - “A Palavra”, he announces that he will develop a project of change for the Archdiocese of Belém, involving the dissemination of the duty to the social, the evangelization of the poor, the good press, and the assistance works, being these actions manifestations of faith and therefore should be priorities in his archbishopric (MENDES, 2006).

This new way of conducting Catholic society was personified in the social practices developed by D. Lustosa. In search of the social and educational work performed by D. Antônio de Almeida Lustosa in Pará, we found a Pastoral letter written by him, and adopted as official reading by State schools. In this sense, we see the concern in bringing to light the reality of the countryman, the hostile universe in which families and children of the Amazon lived, and the guidance in relation to health issues that they did not have access to. Instilled with the principles of Salesianity, this Archbishop took on a strong pastoral mission in several states, such as Minas Gerais, Pará, and Fortaleza, a strong pastoral mission focusing on poor children and the community in general, founding numerous social works, including schools. Given the gap in the study of this important intellectual, regarding the extent and impact of his social and educational work for children and the community of Pará's society, we must study him and understand the way Dom Lustosa built these practices involving the principles of religion and science.

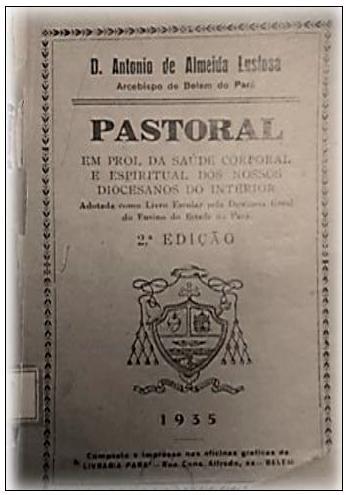

Source: Rare works archive of the Federal University of Pará Library.

Image 3 Schoolbook adopted as official reading by the General Board of Education of the State of Pará - 1935, 2nd ed.

In image 3, we have the cover of a reading, documentary source analyzed in this article. In cultural history, the reading carries several meanings in a specific society, in the work History or the reading of time, Chartier (2009) points out that a reading is produced from a local context, with specific intentions that involve new ways of thinking or perceiving something, being the historian's task to organize, treat, and analyze the representations found in these documents, elaborating scientific and historical knowledge about the past.

In this sense, searching for the author of the work, we found that it was written by the Archbishop of Pará, D. Antonio Lustosa, during his long visits to the congregations in the interior of Pará. Adopted as a schoolbook by the General Directorate of Education of the State of Pará, it is a 2nd edition of 1935, has 54 pages, and is divided into 3 chapters: 1) "The reason of this", which explains why the book was written; 2) "The house", this chapter lists several precautions that must be taken at home to avoid infections and their proliferation among its inhabitants, including children; 3) A short history of the fight and prevention of “paludismo” or malaria - name given by the Italians to the disease, which means “bad air”. There are guidelines on how malaria should be fought in Pará, contemplating also several examples of how this evil was faced in Europe.

In the face of these issues, we realize the important relationship between religion, health, science, and education in the development of school knowledge, clarifying the place of each one of these fields in the life of Pará´s population. It is interesting to observe in this work the relevance that health represents both for the State in the representation of an institution responsible for providing health and education to the population, and for the Salesian priest who takes with him in the 1935s not only the responsibility for the soul of each devotee, but for their physical and spiritual well-being.

This double concern of Father Lustosa can be explained by the Salesian mark that he carries, since his congregation has its origin in the teachings of Don Bosco, which prescribe the importance of physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being for divine and religious Christian communion, as well as for the exercise of the rules of good living in a humanized society.

About the way we should analyze a writing Chartier makes a warning to those who perform the duties of an historian, he "must be able to link in a single project the study of production, transmission and appropriation of texts. Which means to handle at the same time textual criticism, the history of the book and beyond, the printed or written, and the history of the public and reception” (CHARTIER, 1999, p. 18). Therefore, it is interesting to notice, that it is not by chance the selection of this or that reading for circulation among the popular community of Pará. From the 1930s, we have several studies that prove the various ways of organizing the space and time of popular education aimed at the community and the selected teaching programs. For Faria Filho:

Historical as well, the school space and time were being produced differently throughout our history of education and constituted two major challenges faced to create, in Brazil, a system of primary or elementary education that would meet, minimally, the needs imposed by social development and / or the demands of the population (FARIA FILHO, 2000, p.20).

Thus, we intend the analysis of the book published in 1935, as "PASTORAL ON BEHALF OF THE BODILY AND SPIRITUAL HEALTH OF OUR INLAND DIOCESANS” (PPSCENDI), written by a religious and directed to the lower class people that he wants to approach, using not only the scientific knowledge of hygiene, but also the official religious practices (catechism, marriage, baptism, among other practices).

This reading consists of detailed reports about the behaviors, relationships established among the community, as well as the absence of educational practices related to health and childcare. We understand here the concept of education in the broadest sense, as a set of behaviors and knowledge taught and learned by a social group, in a given historical space-time.

The origin of the official book adopted in the schools of Belém is a pastoral letter prepared by Father D. Almeida Lustosa and due to its importance in the context of Belém´s society in 1935, it was transformed into an official book to be used in schools. In the mentioned work, we identify that the reason for the elaboration of the educational- pastoral character reading is the relationship between "rural hygiene and the pastoral munus, is charity and the desire to make the parish work more efficient" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 7), so he says:

Charity, only those who have traveled inland in our Archdiocese can calculate how much the inhabitants of our countless islands, on the banks of this network of countless rivers and streams suffer. Our heart bleeds to see the state of physiological misery of these organisms impaired by impaludence, intoxicated by verminosis. And was it possible to see this man in such a state of misery and go on without doing anything to help him free himself from the ills that afflict him? How many children have confrained our hearts with their morbid, distressing appearance! Premature death or an existence of pain-the only possible prospects-at the very threshold of life! (PPSCENDI2, 1935, 7-8).

In the face of this outburst, Dom Antônio Lustosa demonstrates not only the poverty in which children and their families lived in 1935, but also the precarious conditions of hygiene and health. It is worth remembering that Dom Lustosa, during his archbishopric in Pará, sailed through almost all of Pará's territory making pastoral visits, and checking not only how the congregations in the interior were doing, but also the condition of the poor population. Thus, he learned about the situation of the archbishop in the inland, feeling sorry for the conditions in which the riverside dwellers lived. Seeing this desolate scenario, he had no choice but to free these people from these evils and save the children.

Regarding renowned institutions that engaged in the care of children, we had the Institute for Protection and Assistance to Childhood (Instituto de Proteção e Assistência à Infância -IPAI), located in the capital of Pará, being a reference in care related to mother - child protection and childcare in Pará. It is worth mentioning that this institute went through serious difficulties to maintain itself, thus announcing difficult times not only in the capital of Pará, but for the state of Pará. According to Alves and Araújo

By 1933, IPAI had achieved the respect of the population and especially of the government. The third headquarters of IPAI was already serving a significant number of poor children. Facing difficulties to maintain itself, the institution needed help from the state government to continue its social activities. After the departure of the physician Ophir Pinto de Loyola, due to serious health problems in 1934, IPAI faced serious difficulties and urgently needed its own headquarters. After the premature death of Dr. Ophir Loyola, in Rio de Janeiro, where he went to treat liver cancer, IPAI was renamed "Ophir Loyola Institute", in honor of its founder. (ALVES E ARAÚJO, p. 35,2016).

Regarding this hostile universe that the inland child lived in, in the 1930s, we can revisit it when we perused through the reports of the trips made by D. Lustosa in Pará. In his ten years as prelate, he visited practically the entire territory of the Diocese of Pará, had contact with the community, and was an eyewitness to their behavior, the living conditions in which they lived, the way they related in their daily lives, what made up their food, their work system, and the relationship of this community with religion. On the question of the efficiency of the parish work, Lustosa reports that the malarial fevers are efficient

in destroying the spirits of its victims. The impaled feels completely defeated when fever strikes him. His energy collapses, his plans collapse, his ideals fade. These effects may be common to almost all illnesses; but they vary greatly in intensity. The impaled, we repeat, are a mong the most damaged in their moral breath - a precious gift in the struggles of life. The life of faith that the parish works aim to conserve and develop is continually demanding of the Catholic the effort and enthusiasm. Progress in virtue is all the fruit of victory. Take away a man's willpower and he cannot be a good Catholic. (PPSCENDI, 1935. p.8)

One of the bishop's great concerns is about the influence of good health in parish work before the community and the importance of this in the constitution of the good Catholic. Thus, it is inferred that the good Catholic is the one who moves, practices the habitus of courage, cheerfulness and enthusiasm in the conservation and development of the duties of the good Catholic, which sometimes highlight the qualities for work, hygiene with the body and spiritual life care.

In our congregations throughout the world, the religious service takes place partly in the parish headquarters and partly in different points of the parish territory. Nor can it be otherwise because the population is dispersed and the territory is vast. Towns, between which there was only one league, are in fact six or more leagues apart, because the winding road that connects them, rectified, would be thirty or more kilometers long. Despite the fact, however, that the vicar is transported to different points to facilitate the practice of religion by the parishioners, evidently some of the inhabitants of these large congregations will also have to travel. How many times during the pastoral visitations we heard people say: "If it were not for the fevers, how many people would have come" (PPSCENDI 1935, p. 9-10).

In the face of this happening, about this relationship between education, health and scientific knowledge, we can affirm, therefore, that not only the hygienists had this concern, but also the religious congregations of Salesian nature, when settling in Pará by the 1930s, saw these spaces as an opportunity to exercise the presence and the exercise of Christian sentiment and communion with the divine in their social-christian-educational work. According to Gondra (2000) and Faria Filho (2000) apud Panizzolo (2005) the development of scientific knowledge, especially the medical knowledge, in the figure of the hygienists, were decisive for the construction of the need of the school own and specific space. Thus, the school space became a territory of ideological dispute, where the State created teaching programs, methods, and actions that helped to strengthen the power and social control and, at the same time, the church, embodying the religious missions in the country, expanded its Christian educational works.

As for the challenge of this religious and pastoral mission, fever and locomotion are remembered by the Archbishop as challenges and impasses for the practice of religion, during the pastoral visits, made by the vicars to the riverside communities.

our zealous Vicars who constantly see many of their parishioners prevented by illness from enjoying their ministry - how much they do not feel the persistence of this cause! We have often heard in Belém that it is a grave injustice to accuse our "cabloco" of being indolent. Because - they say - it's not a question of indolence, but of illness, or better, the effect of illness. It is really astonishing that a man, who has just been stricken with fever, takes up the axe to cut down a tree or row for hours on end. And that makes the inland man. But whether or not the tendency of this man to rest is justifiable, the fact is that the tendency exists; the aversion to constant work, the capitulation in the struggle against obstacles, the escape when reaction is required - will fatally imprint its mark on the life of the man intoxicated by malaria. Education, and particularly virtue, can, in spite of everything, give examples to the contrary; but it is up to us to predispose the physical to moral triumphs. Let us pay attention to ordinary cases (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 10-11).

In the section of the Pastoral Letter, called paternal, Antonio Lustosa wishes that the improvement of the state of bodily health be understood by the leaders of the congregations as a matter of necessary charity in striving and that it does good to the soul of the children of the interior. Thus, to be a good Catholic, it is necessary to practice a hygienization of life. Lustosa points out that this work has a scientific content, but will be done in a parternal way, as an extremely useful parish service. And who is the one who takes the parish word to the community, in Lustosa's view? It is the vicar, in his view, a well educated and respected man,

his advice makes an impression on the minds of his listeners. It is not our intention, in this Pastoral, to advise our Vicars to medicate the sick people of their congregations. Absolutely. We want them to make an effort to persuade their parishioners of the necessity of living according to the laws of hygiene. We want them to facilitate their parishioners in the practice of hygiene, suggesting to them what science requires in order not to lack health. We want them to practice that charity which seems directed to the temporal life of their neighbor and contributes so much to his spiritual well-being. (...) The psychology of our inland man is that he can only assimilate the doctrine taught in a way that we can call pastoral (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 12-13).

In view of these statements, we can infer that the inland man is the one who does not know how to read, and when he does, he understands better a simple reading, without many scientific terms. It is a man raised without knowing the precepts of hygiene for themselves or for their children. In many communities, these inland people find it difficult to get to the parish to practice their religion, or they usually attend celebrations that are not officially recognized by the Catholic Church. These are people affected mainly by malaria and verminosis, diseases of major concern for Lustosa when he wrote this Pastoral Letter. Thus, the preparation and publication of this printed Pastoral Letter is part of a larger project of Lustosa, linked to the Salesian mission in the Amazon: to form good citizens and good Christians, from childhood. On the issue of resorting to the principles of science in conducting the work in the interior, Arantes (2011) explains that many hygienist doctors understood that children should be cultivated, and became objects of special care.

In the art of nurturing children, the medical hygienism placed itself as the best ally of the state and to it can be credited, in large part, the emergence of the sense of childhood in Brazil. The child emerges as the future of man and country and its autonomy should be developed (ARANTES, 2011, p. 187).

In the section called microscope, Lustosa gives instructions on what this instrument is, what it is used for, and its importance in hygiene science, showing that Pasteur can demonstrate the existence of microbes in air that seems pure to us and in water that we think is crystal clear. He tells that when he advises a fisherman to prevent himself against mosquitoes,

the guests in his house and in the hold of his canoe, who harass his children, sometimes he [the fisherman] answers: "Come on, if they have to get sick, it's no use”. How often we see healthy people in contact with those who are sick with contagious diseases! "If God doesn't want me to get sick, I won't have anything". And we even find people afraid to take precautions, as if to say: "If I am repulsed, it's worse, because God can punish me”. Beloved children [says Lustosa], never say such expressions. There is a highly offensive sim to Divine Justice which is called tempting God. To tempt God is to get into danger unnecessarily and to claim what one hears among the people: "God said: help yourself, and I will help you" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 18).

This way, D. Lustosa teaches that the doctrine of fatalism must be overthrown, God does not take anyone's life, and we are responsible for our health and hygiene. And D. Lustosa goes on

The holy writ warns us against the danger of leprosy (Leviticus - Chap. XII and XIV). The man who gets into danger and then demands from God the miracle that will save him, wants to oblige the Lord to support his imprudence. God wants us to do what we can, and then in good conscience He will avail us. It is worthy of all praise the man who, to fulfill his duty, faces the dangers without fear. But entirely reprehensible and insulting to God is the behavior of the indolent who does not work trusting in providence, of the reckless one who squanders everything, exposing his family to starvation, saying: "God is great" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 18-19).

Health thus becomes a great gift from God, and we must preserve it. Lustosa argues that we are free to make choices about how to live, where "the fatalistic doctrine denies man his freedom; therefore, it is terribly harmful to him and contains monstrous falsehoods. Never say, dear children: 'If I have to get sick, there is no use in avoiding this or that” (19). Lustosa really assumes a paternal relationship with his parish priests from the inland, which is what the discourse revealed in the analyzed print shows us.

2. Science and Religion in the construction of good citizens and good Christians: a pastoral educational work focused on health and care for children in Pará´s inland.

D. Lustosa, through literary production, also showed concern for the inland children and in his wanderings observed that

with the new generations, other methods can be effective. Children attending schools can learn and - most importantly - assimilate well the indispensable principles of hygiene. To learn only, to know only the theory, is very little. It is necessary that the child assimilates the hygienic precepts in such a way that he feels the need to put them into practice. And how many children in the whole world are completely unaware of school! How many others have attended for such a short time that they have acquired almost nothing! But, besides children, adults also need hygienic rules, and convincing them is not an easy task (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 13).

Thus, D. Lustosa (1935), reveals the reality of access to education for inland children of Pará, where besides not knowing the precepts of hygiene, they are completely unaware of school attendance. This ignorance can be due to the fact that elementary school became mandatory in a constitution of national scope, a year before this writing (1934) and therefore, school was not for everyone. In a certain moment of pastoral orientation, D. Lustosa (1935) relates that the men of the interior are avid for medicines, they treat themselves for illnesses that are focused inside the house and again contaminate themselves with germs. In addition, they take medicine on their own, if a third-party assures them that it will cure their illness. The priest stresses that it is necessary to medicate the sick person, but teaching about hygiene is fundamental. D. Lustosa also reiterates that the educational action on this care transcends the question of charity, it is also a great patriotic work, because the one who loves his country takes care of his children. In relation to this concern with child mortality that moved religious, psychologists, educators and doctors during the 20th century, Alves explains that

with the advent of modern science, they began to worry about the mortality of children, by producing studies concerning the discoveries of the origin of many diseases, as well as preventive methods and medicines to treat them, and in the case of childhood, specifically, some researchers began to produce studies focused on this social segment, which referred to the feeding of the child, the health of mothers, childbirth, the peculiarities of the newborn, bathing, clothing and, especially, research that dealt with the diseases that most affected children (ALVES, 2018, p.8).

D. Lustosa (1935) in the home section, raises the thesis that there are differences between poverty and lack of hygiene. There is a concern in the writing of his Pastoral to explain scientific terms such as prophylaxis and antiseptic, making a point of saying that it means cleanliness. In this way, by knowing the real meaning of the word cleanliness, the inland man can preserve his health, save on medicine, and avoid illnesses. In interior cleaning, domestic animals should be avoided inside the house, because they attract flies and mosquitoes, "spitting on the floor is a very bad habit. Many times children walk on the floor, contracting diseases through contact with this infected floor. Avoid wetting this floor in order to keep it clean" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 22). As for the care outside the house, D. Lustosa explains that it is necessary to "maintain strict cleanliness around the house. No debris, infected mud, stagnant water nearby. "If you have pets, get used to sleeping away from them. Great advice to avoid malaria is this: never sleep without a mosquito net" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p.22).

In the section on water, D. Lustosa explains that although it is often said that water is health and life, in many places it "harbors death". With this warning, he begins the section and disseminates various special cares with water regarding the benefits achieved with the process of boiling it, as well as with the proper storage in a pot and even with the installation and maintenance of the water well, which should be far from the cesspool and sentinas (PPSCENDI, 1935).

When writing about manners, the priest gives visibility to the typical country man, who has not yet had access to medical-scientific knowledge. Regarding children, it is important not to let them put their hands to their mouths, in order to avoid contact with germs

It is a very bad habit of some people to touch their lips with their fingers. These fingers can bring disease germs into their mouths, transmitting them to others. Parents should take the utmost care to keep the hands of small children clean, as they often put them in their mouths. Drinking water in the concave of the hand, taking food into the mouth with it, without washing, is always imprudent (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 27).

Lustosa's concern shows that the inland children needed a pastoral mission that included them, after all these little ones would be the men of the future and needed to be prepared with the appropriate corporal and spiritual care. In this sense, we infer that reason, religion and loving kindness (“amorevolezza”), the preventive tripod of Don Bosco's education system, was also present in this mission faced by the Salesian Archbishop Lustosa. Where: in the aspects of reason we have the presence of science as an important element that must be taken into account in orientations and health instruction; religion as a fundamental element to romanize and make itself marked in the heart and mind of the good Christian, as well as in his cultural practices; finally loving kindness, which materializes through the affection and care that we must have with ourselves and with our peers. The priest tries to get as close as possible to the social reality of the community, giving examples from their daily lives, so it is easier to instill the knowledge that he understands as necessary. In this sense, the example below where he talks about the coexistence between humans and animals, he argues that

In the first place it should be noted that animals also get sick. Also, among them there are diseases transmissible by contagion, there are epidemics that cause herds, shoals, etc. to fall. Let us also note that, among them, the instinct of conservation is also manifested by scruples similar to what science suggests. Give an ox, for example, an ear of corn that has already touched the mouth of another ox, and he will refuse it. It should also be noted that human nature differs from those of brutes; and among them there is also a difference in nature. To vultures, putefractious meat does not cause infections; mud is the habitat of several animals (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 27).

Therefore, the popular saying "Woe betide the smaller animal that the bigger one eats”, or “what doesn't kill you, makes you stronger", "falls to the ground" and cannot be practiced in D. Lustosa's view. These remarks lead us to imagine that the behaviour of the inland man was to breed animals near their dwellings, facilitating the transmission of diseases. Thus, he wants us to understand that hygiene is part of human nature, guided by the principles of science, and that it establishes different care than that given to animals.

Floretsan Fernandes, a great Brazilian sociologist of the 20th century, publishes in "Mudanças Sociais do Brasil" (1979), travelers' reports from Brazil´s inlands, to show the country's socioeconomic conditions. In one of these reports, we find the author of "Viagem Ao Tocantins", a physician of the yellow fever service of Rockefeller Foundation, Júlio Paternostro, stating that the infant mortality rate in Pará´s inland is astonishing. In 1935, on one of his trips, it was found in Igarapé-Miri, that the infant mortality rate was 58% - from January to March 48 individuals died, of which 23 were children. Paternostro infers that malnutrition and ignorance of childcare, associated with malaria outbreaks, act together, increasing the mortality rate among children. (FLORESTAN FERNANDES, 2015).

Regarding the care with domestic utensils: clothes, kitchen utensils, and handkerchiefs, D. Lustosa informs that these are big sources of infection, and gives practical examples of how these infections can occur, based on cases he has certainly witnessed.

Often to give a misunderstood proof of friendship, one does not demand, or permit, the washing of the cup or glass that another person in presence has just used. This false show of trust must be combated, in the spirit of charity. It's a very bad habit that two people eat from the same plate. They do it in some places in the interior out of camaraderie; but who can know if they have a contagious disease? Children are very receptive; they are not immunized like adults against various diseases. However, these careless children, without even suspecting the danger of contagion, are often victims of the imprudence and lack of hygiene of their elders. They drink from their own glasses and allow them to eat from their own plates. There is in this manifestation of affection a great objective evil, albeit unconscious. Almost identical would be the case of someone who gives the child a poisoned sweet on good faith. Let reason guide us and not sentimentalism (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 29-30).

Established cultural practices can become vehicles for the transmission of diseases, D. Lustosa calls attention to this. Orienting that ties between acquaintances should not be made without the practice of hygiene. D. Lustoso perceives that the sense of non-hygiene present in the imaginary of the people from the inland is a manifestation of affection, and of the non impugnance to the tie constituted among acquaintances, being this custom in reality, a great evil in the eyes of the Priest, evil that dwells in the unconscious of each person who practices it. Thus, warns D. Lustosa, "Let us not jeopardize our health or that of our fellow men, by imprudently trusting that perhaps no harm will come to us" (PPSCENDI, 1935, p.28). About the handkerchief as an artifact that should be used with caution, since it is a dangerous object and present among the community.

There is in your house, and it is always with you, beloved Children, a dangerous object. However, you are not careful against it; you even have it in your pocket. It is the handkerchief. Are you afraid of leprosy? Well, the handkerchief of the leper is a danger, because the germs of the disease pass from his nose to his handkerchief. Are you afraid of tuberculosis? The handkerchief used by the tuberculosis sufferer probably contains the bacilli of the disease which almost always attacks his lungs. This is why it is so easy to lend the used handkerchief to other people, even to children. The uncleaned handkerchief is used to wrap edibles, like fruit, bread. You shake the handkerchief next to other people's faces. You hold this handkerchief in your hand for a long time, and you still consider your hand to be clean. Let no one say: "I can do all this because, thank God, I have no illnesses that can be transmitted. But there are many people who think they are healthy and they are not. In case of doubt, prudence and charity order to take precautions that are actually so simple (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 31-32).

The child, for D. Lustosa, needs hygiene practices so much, that it was highlighted in The children section, where several special cares are listed to be dispensed to them, because the child is fragile, needs to be conducted in the educational process, and is a being unable to defend itself from all these harmful agents.

The child - a delicate being, incapable of defending itself by itself from the agents that transmit the enemies of health and life - deserves special hygienic care. Doctors teach that the man who reaches adulthood, in general, has already won the battle of various diseases that were assaulting them in the early years of life. The child who has not yet faced the danger of these attacks is a more exposed life. His defenseless organism is an open field. The intelligence and affection of their parents must supply what is still lacking in the defensiveness of the children, in the human species (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 33).

About the need for guidance, protection and maternal care cites that the act of the child taking the mouth in hands, is as dangerous as leaving a knife within reach, warning about the danger of verminosis.

The child does not distinguish between food and poison. Maternal care must be ensured at all times. And this care generally exists when it is a matter of avoiding accidents or injuries or serious evident dangers. But when it is a matter of avoiding the contagion of diseases, the deficiencies are obvious. You don't leave a razor within the reach of a child's hand; but you allow him to take a piece of bread that has rolled on the ground into his mouth, a key that is everywhere, suck their fingers, and yet you neglect the cleanliness of his little hands! (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 33-34).

The priest claims that enemies of the child are those who are aware of the imminent dangers of unhygienic children and continue to practice inappropriate behavior, putting not only the child's life at risk, but also his relationship with God as a Christian. We Christians have a biblical duty to take care of our children, and by not doing so, we displease God.

Don't let the child put on the head hat of adults, wear someone else's handkerchief, drink or eat someone else's leftovers. Do you love your children? Be true, coherent, rational your affection (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 34)

Thus we understand that parents are accountable to God for the care given to their children, so both the health and the life of the child are of great importance to God, after all He who has gifted them with a child. About the cultural practice of kissing the child's face, Dom Lustosa classifies this gesture as a "false proof of affection" and adds "You should prefer that they give your child a slap instead of a kiss. This false proof of affection can be a stab to the health of this child. For him saliva is often the carrier of very dangerous germs”. (PPSCENDI, 1935, p. 34)

There are also reports about the danger of plants exposed to the children, and warns that there have been cases of children "falling victim to liamba, or diamba: a plant that is fatal for health. Thank God the area is restricted". The section about the child ends emphasizing the place that the priest wants the child and his family to occupy in the Amazon, that is, people who know and practice moral knowledge, good manners and health conservation. And so he concludes by showing that health care founded on scientific bases should also be part of the formation of body, spirit and mind in the modern, Catholic society of the 1935s.

We will conclude this chapter as before by pointing out the morality of life, the good habits, for the preservation of health. God intended that those who profane the laws of morality should, as a rule, have at least part of their punishment, in this life, in failing health. Do you have children? Let us repeat it once again: keep them pure, and besides God's blessings, they will profit in their physical and mental health (PPSCENDI, 1935, p.38).

Concluding remarks

The Impresso "Pastoral in favor of the corporal and spiritual health of our inland dioceses”, deals mainly with special care for children, detailing the hostile universe in which inland children lived. It also approaches the dissemination of hygiene as an element of educational process in the community and propagation about the importance of the search for health treatments on a scientific basis, encouraging the deconstruction of the fatalistic doctrine onstituted until then in this universe of the inland social thought and condemning the practice of self-medication.

The advertising of this paper in churches and schools, has the intention of disseminating new educational project adopted by D. Almeida de Lustosa, which is, to romanize the parish priests of the interior through not only religion, but hygiene practices, since in the vision of this priest, a fragile and unhealthy body has no virtue to perform the activities of a good Christian. Thus, in simple language, we have detailed guidance on education and health, in order to avoid mortality among children, youth and adults, by diseases such as cholera and malaria, frequent ills in the capital and inland in 1935.

By putting this printed material in circulation in the capital and especially in the inlands of Pará, the aim was to constitute in parents the culture of assuming a coherent and rational position in relation to affection with their children, and that they could teach them hygiene care and understand the consequences of non-hygiene. The intelligence and affection incorporated through these educational practices of defense, prevention, and protection of the child strengthen the entire community and his pastorate as Archbishop of Belém between 1931 and 1941.

All this care is part of a larger project, where it is necessary to save the poor children and communities, keep them strong and healthy, give them a useful destiny surrounded by good morals, so that they can contribute to the progress of the Salesian work and Catholicism in Pará.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Laura Maria Araújo. Presença da infância e da criança no Almanaque de Lembranças Luso-brasileiro (1855-1910). IN: Anais do XI Encontro Maranhense de História da Educação.2018. [ Links ]

ALVES, Laura Maria Silva Araújo; ARAÚJO, Sônia Maria da Silva Assistência, proteção e direito à infância em Belém do Pará com a fundação do IPAI (1910-1912). International Studies on Law and Education, 22 jan-abr 2016, CEMOrOc-Feusp / IJI-Univ. do Porto. [ Links ]

ARANTES, Esther Maria de Magalhães. Rostos de crianças no Brasil. IN: A arte de governar crianças: a história das políticas sociais, da assistência à infância no Brasil. Irene Rizzini, Francisco Pilloti. 3ªedição. São Paulo: Cortez.2011. [ Links ]

AZZI, Riollando. As Filhas de Maria Auxiliadora no Brasil: Cem anos de História (1917- 1942). VII. São Paulo: 2002. [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, Agueda Bernardete. A era das congregações - pensamento social, educação e catolicismo. DOSSIÊ: Empreendimentos sociais, elite eclesiástica e congregações religiosas no Brasil República: a arte de “formar bons cidadãos e bons cristãos” Revista Pro.posições. V. 28, N. 3 (84) | set/dez. 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2016-0117. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história ou a leitura do tempo. Tradução de. Cristina Antunes. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2009. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A aventura do livro: do leitor ao navegador. Tradução Reginaldo de Moraes. São Paulo: Unesp, 1999. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Florestan. Mudanças sociais no Brasil. 3ª Edição. São Paulo, Difel, 1979. [ Links ]

FILHO, Luciano Mendes de Faria; VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. Os tempos e os espaços escolares no processo de institucionalização da escola primária no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Educação, mai/jun/jul/ago 2000 Nº 14. [ Links ]

FOTOGRAFIA DE ANTÔNIO DE ALMEIDA LUSTOSA E O INTENDENTE MAGALHÃES BARATA. Arquivo da ACADEMIA PARAENSE DE LETRAS. [19--]. [ Links ]

FOTOGRAFIA DE ANTONIO DE ALMEIDA LUSTOSA COM INTELECTUAIS NA ACADEMIA PARAENSE DE LETRAS. Arquivo da ACADEMIA PARAENSE DE LETRAS. 1953. [ Links ]

JORNAL A VOZ DE NAZARÉ. DOM ANTONIO LUSTOSA - O BISPO DA JUSTIÇA SOCIAL. Período de 18 a 24 de setembro de 2015. p.5. [ Links ]

MENDES, Mayara Silva. Conflitos Religiosos e relações políticas no Pará (1930 - 1941). São Paulo, 2006. Dissertação de Mestrado. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Livros de leitura e o ensino no Brasil: campos de disputa, espaços de poder. Anais do 15° Congresso de Leitura do Brasil.Unicamp.2005. [ Links ]

PASTORAL EM PROL DA SAÚDE CORPORAL E ESPIRITUAL DOS NOSSOS DIOCESANOS DO INTERIOR”. Livro Oficial Escolar. 2ª edição de 1935. [ Links ]

Received: July 28, 2021; Accepted: October 15, 2021

text in

text in