Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-123

Papers

Baroque and Education in Portugal in the Seventeenth Century: Josefa de Óbidos1

1Universidade Estadual de Maringá (Brasil). celio_costa@terra.com.br

2Centro Universitário de Maringá (Brasil). giovanaversolatto@gmail.com

This paper’s aim is to identify in what way the Baroque contributed to the education in Portugal in the seventeenth century through the work of Josefa de Óbidos. Our hypothesis is that the Baroque was one of the elements in the educational process of that period because of its role in fulfilling the formative purpose of the time. To that end, we analyzed some of the referred artist’s works with the purpose of investigating the premises instilled in the images in order to identify her artifices of persuasion or guidance, which have corroborated with the educational process of the faithful/subject. We concluded that the Baroque's stylistic elements granted a directive character to Josefa's works, which contributed to guide the faithful/subject in their experience and learning of the Catholic faith and thus to the creed's perpetuation and preservation.

Keywords: Baroque; Josefa de Óbidos; Education in the Seventeenth Century

O objetivo deste artigo é identificar de que forma o Barroco contribuiu para educação de Portugal no século XVII, por meio das obras de Josefa de Óbidos. Nossa hipótese é que o Barroco tenha sido um dos elementos do processo educacional do período, por cumprir com o propósito formativo à época. Para isso analisamos algumas das obras da referida artista, com o propósito de investigarmos as premissas incutidas nas imagens, para identificarmos os artifícios de persuasão ou condução, que corroboraram para o processo educacional do fiel/súdito. Concluímos que os elementos estilísticos do Barroco, viabilizaram às obras de Josefa um caráter diretivo, que contribuiu para a condução dos fiéis/súditos à experiência e aprendizado da fé católica e, portanto, à perpetuação e conservação deste credo.

Palavras-chave: Barroco; Josefa de Óbidos; Educação no Século XVII

El propósito de este artículo es identificar cómo el Barroco contribuyó a la educación de Portugal en el siglo XVII, através de las obras de Josefa de Óbidos. Nuestra hipótesis es que el Barroco fue uno de los elementos del proceso educativo de la época, para cumplir el propósito formativo de la época. Para ello analizamos algunas de las obras del referido artista, con el fin de investigar las premisas inculcadas en las imágenes, para identificar los dispositivos de persuasión o conducción, que corroboraron el proceso educativo de los fieles / sujeto. Llegamos a la conclusión de que los elementos estilísticos del barroco hicieron de las obras de Josefa un carácter orientador, que contribuyó a la conducta de los fieles / sujetos a la experiencia y el aprendizaje de la fe católica y, por lo tanto, a la perpetuación y preservación de este credo.

Palabras clave: Barroco; Josefa de Óbidos; La educación en el siglo XVII

Introduction

This research is dedicated to the study of the History of Education in Portugal in the seventeenth century from the perspective of art, establishing the Baroque as one of the elements of that period’s educational process. The Baroque style was an artistic movement that developed in the seventeenth century and encompassed several realms of expression, such as music, literature, architecture and painting. This work focused mainly on the painting sphere, and its primary source is found specifically in the paintings of Josefa de Ayala e Cabrera (1630-1684), better known as Josefa de Óbidos - a painter who gained prominence in the Portuguese town of Óbidos.

In the interest of identifying if the Baroque contributed to the educational process of seventeenth-century Portugal and in what way, this work will seek to demonstrate the formative purposes of this period and analyze how this stylistic movement and Josefa de Óbidos’ productions influenced the education of seventeenth-century Portuguese individuals. In light of Saviani’s (2013: 43-44) assertion that education is meant for the furthering of man, the study will seek a deeper understanding of the situation of seventeenth-century man in order to determine what this furthering meant and in what way the Baroque has contributed towards that goal.

The reason why art was chosen as the basis for this study’s subject matter is due to its role as one of society’s formative elements. In this sense, to disassociate art from the History of Education would be to the detriment of knowledge since, as Barbosa (2012: 31) states, imagination is fundamental for human thought, be it in any age or activity, and by the same token, art and imagination are inseparable. Thus, a close relationship is established between art and cognition.

Moreover, according to a study by Magalhães (1996: 438), although the literacy of Portugal’s subjects had shown some advances in the sixteenth century, this tendency suffered a decline up until the last two decades of the seventeenth century. There was “a new period of hardship and stagnation, along with a general crisis in economic, political and cultural aspects [...] restricting the teaching of Latin in small towns.” Therefore, in the period between 1630 and 1684 in Óbidos - which is a small town - we presume that its population was made up of an illiterate majority and thence the artistic images may be appreciated as an important channel for conveying educational principles.

One other point to consider is that, as stated by Gombrich (2011: 135), in Gregório Magno’s view, in the sixth century images began to be used for the teaching of religious precepts, bearing in mind that “many members of the church could not read or write, and that in order to teach them these images were as helpful as drawings in an illustrated book for children”. This is especially true for Baroque art pieces, as argued by Argan (2004: 7), for “they had a practical, political and religious aim - or rather, as religion flowed into politics, the aim was simply political.”

According to Ferreira (2004: 59), Portugal’s formal education was controlled by the Society of Jesus. It had been founded in 1534, but in the end of the sixteenth century it already had schools in several of Portugal’s regions. Since the formal education promoted in this period was mainly directed by the Jesuits, it is necessary to note the educational purposes by which they oriented themselves. Ferreira (2004: 60) implies that “the Jesuits’ actions had the aim of maintaining the prevalence of Catholic doctrine and the cultural foundations associated with it, which were quite shaken by the Humanists’ free thought.”

In this sense, the Baroque conformed to the Society of Jesus’s goals. Or rather, the two of them were guided by the same spirit, the same purposes, because their actions were imbued with the mission of preserving the Catholic faith along with the interests of the clergy and the Crown. By means of rational artificiality and dramatic impetus, art was able to convey meanings to the faithful and subjects because Baroque paintings were directive, as stated by Maravall (1997: 135), or persuasive, as Argan (2004: 8) puts it; from his point of view, “to persuade means to solicit and believe something which is not present but nonetheless places itself in the horizon of things that are possible.”

These factors that were presented allow for an initial inference that education, art and history are all involved in an interdisciplinary dialogue whose end is to value the knowledge pertaining to human activities. They also provide insight into the Baroque: the stylistic movement that manifested itself as the expression of an age through dramatic, ennobling, light-and-dark contrasting, exaggerated pathways, and concomitantly as a guide of human conduct.

Josefa de Óbidos

Josefa de Óbidos was born in Seville, 1630, and died in Óbidos, 1684, where she lived for most of her life. Serrão (1985: 3) describes her as an estimable painter of still life, the Paschal Lamb, paintings for family devotions, works made on copper and religious retables, as well as an etcher. According to Hatherly (2016: 101), her career as a painter granted her notoriety and lasted for 38 years - from 1646 to 1684. During this period she produced more than 100 works, most of which were signed and dated.

As stated by Serrão (1985: 10), Josefa de Ayala e Cabrera was the daughter of Baltazar Gomes Figueira, a Portuguese man born in Óbidos, and of Catarina de Ayala Camacho Cabrera Romero, an Andalusian noblewoman. The couple met in Seville, to the detriment of Baltazar’s military career, which had been short-lived due to his release to pursue the craft of painting. They moved from Seville to Portugal when Josefa was five or six years old to live in the city of Peniche, where Baltazar produced some works for the local churches and over the course of his life until their deaths in Óbidos.

She was born in February 1630, and in the twentieth day of this month she was baptized in the Parish of Saint Vincent of Seville. According to Serrão (1991: 19-25), she was taught under the patronage of Francisco de Herrera el Viejo, a renowned painter from the city whose vaporous and unfettered Baroque art style has no point of contact with either her or her father’s art. Inside the walled town of Óbidos, as described by Serrão (1985: 10), the artist lived by the soft breeze of the seaside and in the peacefulness of the Quinta da Capeleira, her personal address.

As Hatherly (2016: 101) points out, Josefa de Óbidos went to the convent of Sant’Ana in Coimbra between the years of 1644 and 1647, where she received an ecclesiastical education but chose not to live as a nun. At the time, women2 who either did not marry or were nuns would live under the wing of their parents, so to speak. But for Josefa, that wasn’t the case: she emancipated herself legally and lived economically independent from her family through her artistic work.

After the death of Baltazar Gomes Figueira (her father and teacher) in 1674, Josefa came to live in his house at Rua Direita with her mother and two nieces: Josefa Maria and Luísa, the daughters of her sister Antónia d’Ayala (Serrão 1991: 22). In July 13, 1684, while severely ill, she wrote her will and died in July 22 of the same year, leaving her possessions to her mother and two nieces.

The Baroque as an educational tool

In the interest of advancing in our analysis of Josefa de Óbidos’ works and verifying the educational principles manifested in them which have contributed to the teaching of Portugal’s subjects in the seventeenth century, specifically during the artist’s lifetime (1630-1684), it is necessary to elucidate our understanding of the meaning of ‘education’. In Saviani’s (2013: 43-44) view, education is meant for the furthering of man and it has been so in all ages, and though its aims may differ, the attention it turns towards man remains constant. For this reason, to know mankind in a deep sense ought to be one of educators’ main concerns:

what good is education if it isn’t oriented towards the furthering of man? A historical overview of it reveals how it has always concerned itself with forming a certain type of man. The types vary according to the different requirements of different time periods (Saviani 2013: 43).

When addressing this matter, we are immediately faced with a human activity, namely, the realm of values (moral, spiritual, relational etc.), which can only be understood through the lens of human reality. In turn, ‘human reality’ may be conceptualized as the entire context where man is situated; as Saviani (2013: 44) puts it, his space and time. It refers to one’s dependency upon nature and all that exists independently from human action, such as fauna, vegetation, climate, physical space - entities of man’s natural environment, and also to the relationship to one’s own cultural setting, such as man’s historical heritage, his language, customs, traditions, as well as economic, institutional and governmental conditions. This placing of the individual into the world in a given time and place is synthesized by Saviani (2013: 44) as the “situation of man”.

Education’s role is to further man and enable him to know and transform the elements of his situation. In that sense, he is given a task:

Values indicate the expectations and aspirations that characterize man in his effort to transcend himself and his historical setting; in this way, they mark that which ought to be in opposition to that which is. Valuating is the very effort to transform what is into what ought to be (Saviani 2013: 46).

This gap between what is and what ought to be, between values and valuating, is vital to humanity, without which existence itself would be destitute of meaning (Saviani 2013:46). One can appreciate, then, that the aims of education are equivalent to those that pertain to human necessity, that is, to bring into reality that which is by transforming it into what ought to be. In Saviani’s (2013: 48) view, “the delineation of educational goals is dependent upon the priorities dictated by the situation in which the educational process is played out.” When a situation has an established hegemony with principles to be perpetuated, its educational goals will consequently be compatible with them and thus have the intent of legitimizing the education of man according to such principles.

As we turn our attention to the situation of Portugal in the seventeenth century, we identify paramount characteristics to the education of man, as well as the institutional structures that grounded such goals. As stated by Paiva (2004: 79-80), in this period the king was the highest representative of God on Earth and had the mission of helping his subjects ascend to salvation. Therefore, the piety to be displayed in the lives of all was his responsibility: an ordinance appointed by God, legitimized by society and enabled by the Church. Thence, our hypothesis is that art has contributed towards that mission by means of educational principles that were compatible with the interests of the Crown.

In that sense, Ferreira (2004: 58) points out that with the purpose of reinforcing Catholic orthodoxy and perpetuating the decisions made in Trent, the State and the Church would not allow the development of instances of knowledge which didn’t improve upon already established models. Church, Inquisition and Crown became a three-part pillar to support the advancement of Catholich faith and their actions would have significant repercussions in the realms of education and culture. The Baroque synthesized the consequences of this in the cultural sphere:

art sought to impress through the exuberance of the elements, the arguments or the drama displayed in the scenes or depictions. The Baroque is an aesthetic consequence of this impossibility of presenting evidence dictated by the criterion of reason because it translates an artistic worldview characterized above all by the wish to captivate the observer through form and movement, to convert them through the decorative or argumentative apparatus, to suggest by means of the drama portrayed in the images or the power of metaphors (Ferreira 2004: 58).

The Jesuits were tasked with an educational mission, and through them Catholic doctrine reverberated in education with the objective of instructing Christendom both religiously and intellectually-wise. Paiva (2004: 81) asserts that schools were envisioned to act on behalf of the Church with the aim of teaching truth and the way to the truth, and according to the alterations of the social reality in which faith was fostered, “it was natural for the king to seek within the clergy the means to accomplish the teaching of letters in the terms of new social demands.”

Ferreira (2004: 60) points out that the efforts to expand Jesuit schools were associated with a pedagogical approach which, from the standpoint of a unifying organization, encompassed all of the schools the order had around the globe. “The Jesuits were undoubtedly able to quickly organize a well-articulated system and which was quite suitable for the ideological principles that oriented them” (Ferreira 2004: 61). The Society of Jesus operated with the aim of instituting schools and, by way of them, upholding the principles of Catholicism.

As stated in Saviani (2012: 83), the education promoted by the Society of Jesus was systematized: “once education is explicitly held as a main focus of attention, involving the development of intentional educational action, then systematized education will emerge”. By contrast, the pictorial activity that took place in the Baroque period in Portugal either through the works of Josefa de Óbidos or any other painter from the same period had unsystematic educational principles whose ultimate goal was not to teach, strictly speaking, but they still played that role nonetheless. Saviani also sheds light on this form of education:

in all segments of society, people communicate while oriented towards aims that are different from the aim of educating, but despite that, they do educate, and they do it amongst themselves. That is known as unsystematic education: there is an educational activity being carried out, but in the level of innate conscience - in other words, it happens concomitantly to another activity which is properly carried out in a deliberate sense (2012: 83).

The Society of Jesus promoted Catholic doctrine in a systematic way by means of its teaching method and art did the same through the Baroque. As a cultural consequence of its situation, art taught, even though this was not its main goal. The art pieces were commissioned especially to bring a sublime sense of beauty to churches, monasteries and convents, as well as to elevate the court and display the social distinctions between the classes in contrast to those who did not have access to such ornaments.

As Paiva (2004: 80) illustrates, the configuration of the seventeenth century determined that the social body should be set up to recognize a hierarchical dynamic in which, since the king was Catholic, so should be his entire kingdom. In that sense, one can appreciate the pedagogical relevance of art, since through its images it contributed towards the desired educational principles of the time: the edification of good Christian subjects, after all, “a Christian society was the only possibility for that time” (Paiva 2004: 80).

The Holy Office (also known as the Tribunal of the Inquisition) ensured that the works would abide by sacred themes, distant from the threat of paganism and so as to meet the ordinances of Trent. Gonçalves (1990: 111) claims that the Counter-Reformation brought important shifts in sacred art which led artistic production through a different path from the one where Renaissance art had walked, and he attributes this iconographic reform to the Council of Trent.

The Council of Trent was fully aware of the pedagogical value of visual depictions and, as stated by Gonçalves (1990: 112), established some guidelines, such as refraining from lasciviousness, dissolute beauty, dishonesty and elements that caused confusion, disorder or disruptions; furthermore, nothing profane should ever be seen in the house of God. Additionally, all images elaborated for the interior of the temples would have to be approved by bishops. Hence, the artistic freedom that had been characteristic of the Renaissance was ruled out and the themes became increasingly repetitive, in a setting where “art started to give special emphasis to scenes of miracles, of the mystic exaltation and to the theme of martyrs - scenes that served as tools for catechism.”

These ecclesiastical dictates were valid for all Catholic countries, and Portugal was no exception. Gonçalves (1990: 112) reveals that in September 12, 1564, Cardinal Don Henrique demanded that Portuguese tribunals collaborate with the enforcement of the Tridentine decrees and harmonize canon law with civil law. In order for the ordinances of Trent to be incorporated to the ecclesiastical practices of Portuguese bishoprics, thirty-six meetings with the bishops had to be held (Gonçalves 1990: 113).

Gonçalves (1990: 113) also asserts that the guidelines of the Council of Trent with regard to sacred art were mentioned in Portugal for the first time in 1565 with the Constitution of the Archbishopric of Don João de Melo of Évora. Subsequently, they were also found in 1568 in the Second Extravagant Constitutions of the Archbishopric of Lisbon, and in 1585 in the Synodal Constitutions of the Archbishopric of Porto. In all of them, the dictates are similar to those that were prescribed in Trent, with an additional one: “to remove aged images from their places” (Gonçalves 1990: 113). In other words, old paintings whose aesthetics probably matched that of the Renaissance would have to be removed. And ever since, the amount of works which were left unknown to us because of such an ordinance is immeasurable.

Some of the themes that used to be depicted before the Tridentine period were outlawed and they gradually faded from Christian art over the course of time. The emphasis placed upon the beauty of the human body and nudity as an expression of beauty would no longer be allowed to be reproduced, for they defied the Council of Trent’s orders and provided artists with an undue amount of leeway. The images where Mary, the mother of Jesus, was present also were also thoroughly debated. Her suffering in the image of Calvary was one of the main points of contention: as she was a wise woman, it could not be excessive, but her expression also could not be indifferent because she loved her son. Another aspect of the images with Mary which caused a bit of turmoil was related to the works that depicted the nursing of Jesus. As Gonçalves (1990: 117) puts it, “such a human vision of the Mother of Jesus displeased the Post-Tridentine Church, with its ever-present fear of misrepresenting the divine”.

Hence, the Holy Office concerned itself with enforcing the edicts of the Council of Trent in order to accomplish the general goal of the clergy and consequently of the king. In short, their work was meant to carry out what they understood by ‘divine will’. To that end, Catholic faith could neither be altered nor shaken by external heresies, no matter if they came from the Protestants or the Humanists, and the institutions which upheld the Faith were prepared to do away with dissident ideas. Art belonged to this strategy, and in light of that fact it would surely be outlawed when it strayed from its pre-established aims of perpetuating the dogmas of the Holy Roman Church:

religious art had always been destined to the function of playing the role of a mediator, instructing and captivating believers by means of its fascinating lesson. The Counter-Reformation did nothing but reactivate this tradition in full force, thereby cleansing art from the impurities that the pagan excessive worship of beauty had tainted it with (Hatherly 1991: 73).

Religious doctrine stated that the individual should refrain from sin to attain their salvation, and therefore the mission of seventeenth-century man was an arduous one: to better himself as an individual in order to gain divine salvation. We consider this an arduous task because in the Christian worldview human nature is sinful and the pursuit of sanctification is a struggle against one’s very essence, corrupted by the original sin of Adam and Eve.

Some elucidation on this point can be found in the passage by the Apostle Paul in his Letter to the Romans, chapter 7, verse 19: “For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do” (King James Bible 2004), which refers to the constant struggle of man against his own flesh so that he might become worthy of salvation. Conversely, Protestant interpretations of this theological matter, which were considered as heretical, upheld the maxim of “Sola Gratia” (By grace alone), i.e., salvation would only be attained through divine grace and not solely by works. To understand such a view, once again we ought to turn to a passage by the Apostle Paul in the book of Ephesians, chapter 2, verses 8-9: “For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: [it is] the gift of God. Not of works, lest any man should boast” (King James Bible 2004).

This is most definitely a point worth elucidating, since the contradiction between humanity’s current, sinful state - that which is - and the state that still has to be attained, the immaculate one - that which ought to be -, is directly reflected in the Baroque aesthetic, especially when one appreciates that from one state to the other there is the hiatus of the unattainable. This dynamic can be inferred from the drama that is present in the images, the constant contrasts, the exaggerations, the emphasis on suffering and, overall, in the spirit in which the Baroque is immersed. Hatherly (1991: 73) argues that this spirit is of a paradoxical nature: “If art is in itself a form of illusionism because it paints reality but is not reality, (ceci n’est pas une pipe!), for the Baroque’s pan-religious conception not even reality itself (which is the world) is real, because it is only the appearance of something else, something invisible, of which all visible things are but a hint”.

The representation of Christ is used to favor this premise, as can be analyzed in the artworks that display his suffering. Filled to the brim with meaning, they elicit an intuitive impact upon the observer, instilling in the devout conscience a sense of unworthiness and thus of their utter dependence on Christ for the forgiveness of sins and, as a result, their own salvation. Images with a dark background accentuate Jesus’ pale skin and create a contrast which highlights his blood and its intrinsic meaning.

Another important contrast can be brought about by the use of exaggeration, the exuberance and splendor of architectural monuments, the pictorial details and embellishments. This contrast is not immediately tied to another visual element, as in the case of tonalities. Rather, it is present in the reality of the observer: as he compares himself with the grandeur of the Baroque, he perceives his own being as insignificant, “for that which is superior can never be revealed directly to that which is inferior, without the mediation of the symbol-image” (Hatherly 1991: 73). This dialectic relationship does not reflect itself only in the religious spectrum, though this could also be the case; once again, it is closely tied to the unattainable: between divinity and humanity, nobility and poverty, courtiers and merchants, kings and subjects - all of which are structural contrasts necessary to the social strategy of the seventeenth century.

In the work “Baby Jesus, Savior of the World” (Figure 1) of 1673 there is a chain of flowers, a theme that is a recurrent in Josefa de Óbidos’ paintings, in which Jesus appears wearing a lace trim robe and standing on a pillow, with stylized sandals and a globe under his arm representing the world. All in all, this is a set of elements that hint at the life of a child from a noble family and not at the life of Jesus, the son of a carpenter who was born in a manger. The splendor, the deep sense of refinement, the sheer abundance of details, and the adornments are all part of the Baroque aesthetic, which imbued its characters with value, infusing new meaning into the observer’s conscience of the figure that was represented, since Baby Jesus could not look like a common child.

Source: Serrão, Vitor (1991): 91. Josefa de Óbidos and the Baroque period. Lisbon, TLP - The Portuguese Institute of Cultural Heritage.

Figure 1 Baby Jesus, Savior of the World; Oil painting; 95 cm x 116.5 cm; Mother Church of Cascais; Josefa de Óbidos, 1673.

Thus, in each case we understand that “religiosity, either earnest or imposed, extended itself onto everything, constituting an imaginary world as palpable as the natural one” (Hatherly 1991: 71), and that the focus of education in Portugal in the seventeenth century was aimed at the instructing of man and overlapped with underlying religious educational principles. Standing on the foundations set up by the Crown and the Inquisition, education manifested itself in iconoclastic culture through the Baroque aesthetic, promoting catechetical and consequently educational art forms. One also observes that the desired value (salvation) directly unfolds in the iconographic depictions of the Baroque, providing images with dramatic power, strategic contrasts and pictorial formulas which upheld the interests of the Church.

An analysis of Josefa de Óbidos’ works and its constitutive aspects

Apart from the isolated analysis of Josefa de Óbidos’ works, the array of her paintings has also much to be explored, since her creative productions act as a guide for each of her phases, as well as for the historic tendencies that art has either witnessed or endorsed. The present research has taken 98 works into consideration, which correspond to a significant part of the artist’s known production and were gathered for the exposition “Josefa de Óbidos and the Baroque Period”. This study plans to verify the themes and the elements that were most frequently depicted in her works.

In succinct terms, elements which are used repeatedly configure not only the painter’s aesthetics but also the tendencies that are characteristic of the Baroque movement itself, as well as the themes chosen by Josefa. Of all the themes depicted by her, the religious one is the most constant, since there are sixty-seven religious paintings and three religious engravings and twenty-seven paintings and one engraving containing everyday themes. To structure the analyses in a systematic fashion, we have divided her works that were meant to narrate religious scenes into two groups: works with biblical scenes (which amount to thirty-five) and works with scenes of saints who were later canonized (which amount to twenty-one).

To conduct the analysis, we will suppose that the use of engravings as models or sources of inspiration for paintings was a universal practice during the Baroque period. Either copied in their entirety or interpreted, sectioned and combined with other motifs, the Italian, French and Flemish engravings have birthed hundreds of other paintings of all genres, and which are found in all Western countries (Sobral 1991: 51). Although Josefa did indeed copy several works, her production has a very relevant vision. Each work would illustrate a message, for, as has been discussed earlier, art devoted itself to this catechetical, narrative role. On the other hand, what did the still-life paintings mean to teach? What was instilled in the depiction of flowers, fruits, and sweets?

In a context which included the habit of attributing a hidden meaning to all things, it is only natural that many of the works produced then were enigmatic, hieroglyphic, symbolic, for their purpose was to convey a lesson hidden in appearances; such a lesson could not be represented truthfully, but it could be hinted at by means of allusion and allegory (Hatherly 1991: 71).

We find Hatherly’s point on the metaphorical illusionism inscribed in Baroque paintings persuasive, which had a tendency to reveal things at a superficial level and at the same time to conceal enigmatic meanings. However, the still-life works crafted by Josefa are marked by a more gracious, decorative nature - a testament to her humble ways of perceiving artistic elements. On the subject of the Bodegones of Josefa de Óbidos (which is how the Portuguese and Spanish used to call the still-life art genre), Serrão believes they “reflect more of a certain descriptivist curiosity than of elaborate edifices of symbolic meditation; besides, usually the clients themselves for whom these paintings were made were not sensitized to them (Serrão 1991: 40).

The way how Josefa addresses some themes, with her systematic naiveté, is noted by some critics as a form of “paintings boys as one would paint cakes”, with “a lace trim religiosity, gluttonous and ultimately sublime in its own pathetic innocence” (Serrão 1991: 41-45). In any case, though she took part in the Baroque in a town court with a serene audience, her still-life works - which make up 26% of her known productions - do have underlying meanings. One ought to consider, for instance, that in Naritomi’s (2007: 39) view, the sugarcane cycle was in its golden age. The century of sugar lasted from 1570 to 1670 and, therefore, to conceive of paintings depicting sweets may have conveyed a message that was significant to those times.

Sugar represented wealth. It was directly linked with economic power and thus to the rise of the merchant class that used to commercialize this resource. One infers, then, that to have still-life works with the depiction of sweets could work as a form of communicating one’s recent ascendance into a new financial standin. This would explain the importance of plenty and exuberance, as well as the refinement in details - features that are an exact match to the artistic style of Josefa de Óbidos.

Next, we will conduct an analysis of the work “Still-Life with Sweets and Flowers”, which demonstrates the relevance of sugar for the artist and her clients. In the painting, the elements we plan to analyze have been enumerated with the aim of investigating the possible meanings that may be inscribed in the elements depicted. We will put forth some suggestions on their meaning, but without deeming them as final.

The veiled manner of addressing some themes as if to steer away from the interference of the Inquisition or Catholic morals was quite common, as Hatherly explains: “To conceal things while also calling for the unveiling of that which was concealed; this is what poetry and paintings that carry an encrypted message do” (Hatherly 1991: 73). Be that as it may, this is a possible way of interpreting the work, not a definitive one.

Source: Serrão, Vitor (1991): 205. Josefa de Óbidos and the Baroque period. Lisbon, TLP - The Portuguese Institute of Cultural Heritage.

Figure 2 “Still-Life with Sweets and Flowers”; Oil painting; 85 cm x 160.5 cm; The Anselomo Braamcamp Freire Santarém Public Library; Josefa de Óbidos, 1676.

Source: Serrão, Vitor (1991). Josefa de Óbidos and the Baroque period. Lisbon.

Figure 3 Indicative illustration of the elements of “Still-Life with Sweets and Flowers”, by Josefa de Óbidos.

The first element enumerated represents the ginjas (sour cherries) (1), which are a type of cherry with a more acidic flavor. They are less rounded than common cherries and taste less sweet, so for that reason they carry a less gracious meaning. Hatherly (1991: 76-77) argues that while innocence is attributed to cherries, ginjas convey a character of perfection and suffering. The second element enumerated represents the Eggs of Aveiro (2), a typical candy from the region of Aveiro; this confectionery is made using egg yolk, sugar and water, which are enveloped by a mass similar to that of the sacramental bread. The adornments around the “Eggs” are made with ribbons, giving them a jewel-like finish.

Due to the presence of jewels, the Silver Platter with golden details (3) which contains the sweets is incredibly detailed. The glimmer in some of the platter’s angles demonstrates the artist’s ability in meticulously illuminating her work. The sweet (4) whose covering resembles a flower could be the “Queijada of Graciosa”*, with a filling of milk and eggs (a recurrent pattern). Right next to it, there is a long sweet (5) whose appearance leads us to presume that it could be the “Pillow of Sintra”*, whose puff pastry envelops its filling of eggs and almonds.

As revealed by the title, this painting does not refer solely to the sweets, but also to the flowers, which carry important meanings for the sense of the compositions. Serrão (1991: 248) and Hatherly (1991: 82) can help us identify these inherent meanings. We find, for instance, that one of the flowers is repeated nine times in the artwork: the poppy (6), which stands for sorrow. Barely visible in the dark background, the flower garland shows the vine flower (7), whose sense is good will.

Next to the vine flower, the tiny ox-eye daisy (8) can be seen, a flower that could remain unnoticed due to its minute size; its meaning is suffering. The carnation (9), alone and slightly timid, appears to be turning its back towards the observer, as if it didn’t wish to be noticed; its meaning relates to desire and affection. Lastly, there’s the sweet briar (10), which represents beauty, and the yellow daisy (11), which stands for mercy.

flowers are often typified as the archetypal figure of the soul, as a spiritual core [...]. If the allegorical use of the flower is vast, the use of floral symbolism to laudatory-mystic purposes is so frequent in the seventeenth century in all arts and literature that it would not possible to give here even a small idea of its magnitude (Hatherly 1991: 79).

After briefly uncovering all of these meanings and highlighting some elements, it is now possible to build interpretations around the work. As seen earlier, the composition brings together ginjas (perfection and suffering), poppies (sorrow), vine flowers (good intentions), ox-eye daisies (suffering), a carnation (desire and affection), sweet briars (beauty) and daisies (mercy). This assortment of meanings may express a narrative which speaks to other works.

The carnation can be the starting point for this interpretive exercise: alone and “shy”, whose meaning is desire. One could consider, for instance, that if it were painted yellow, it would stand for ‘distrust’ and if it were painted white, it would mean ‘chastity’. But rather it was colored in red, connoting desire; hence, we opt to interpret this element in that sense. Next, we turn our focus to the poppies. They hint at the idea of sorrow, since even in the midst of the fulfillment of other pleasures linked to taste a desire that is not satisfied is still present, which elicits such a negative feeling. Much in the same way, suffering is also represented by the ginja and the ox-eye daisy. In any case, in painting the yellow daisies the artist pleads for divine mercy, and she also reveals her own good will by means of the vine flowers, even though they do not stand out in the composition.

These possible interpretations, along with many others, arise out of the mythologizing spectrum of the Baroque through the use of the contrasts and exaggerations, out of the conventions that imbue the elements of nature with meaning and emphatically censor certain themes. In short, these are decorative paintings that reveal the importance of a product (sugar) and the social tendencies of a time period (the rise of the merchant class). Also, at the same time, they work as educational tools because they convey religious and also enigmatic themes by way of the intimate messages contain in them. The importance of these decorative works for art as a whole cannot be understated, because at the end of the analyses they have offered much more than the testimony of an age.

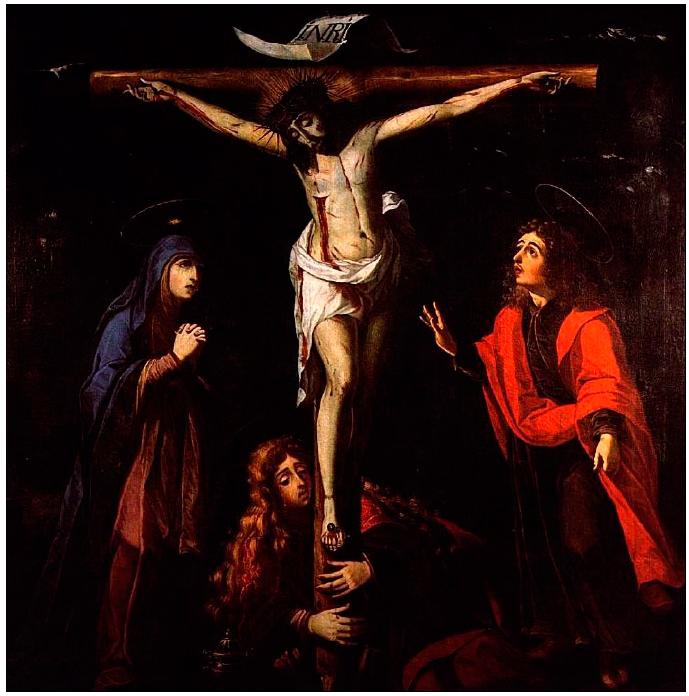

Lastly, we will conduct an analysis of “Calvary” - an iconic painting both for Josefa de Óbidos’ productions and for the Baroque movement. As is the case in practically all of her works, it does not have an emphasis on visual depth (perspective) and it has an extremely dark background. In this work specifically we suppose that there is a purpose for this artistic choice: apart from creating the contrasts between light and dark, it refers to Jesus’s death on the cross, which is described in the Bible as a time period where the world was covered in darkness: “Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land unto the ninth hour” (King James Bible 2004; Matthew 27:45). Still, there is a flash of light that comes from above, and both the robes and Christ are lit up by it.

Source: Serrão, Vitor (1991): 222. Josefa de Óbidos and the Baroque period. Lisbon, TLP - The Portuguese Institute of Cultural Heritage.

Figure 4 “Calvary”; Oil Painting; 160 cm x 174 cm; The Holy House of Mercy of Peniche; Josefa de Óbidos, 1679.

Each of the characters displayed in the painting will be analyzed separately in order to examine the possible meanings instilled in their representations. In the Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 27, Verse 56 (King James Bible 2004), the biblical narrative states that during the act of the crucifixion some women were present, and the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 23, Verse 49 (King James Bible 2004) states that all of Jesus’ friends were present. This observation is relevant in the sense that it relates to Josefa’s choice of depicting three characters around the cross - Mary, Mary Magdalene and John. Such a selection could have its own potential purposes, and it could be the case that the artist herself was not the one responsible for this choice since, as has been pointed out earlier, many of the paintings either used to be based on engravings or were derived from other paintings.

We argue that there is a pretense in this selection, for Baroque paintings employ scenic elements abundantly and in a setting where there could be a group of people, only three figures were chosen to be depicted. By way of this choice, the artist implies to the imagination of the faithful that this episode supposedly occurred in the presence of these three single characters; each one of them has their own representativeness. On the topic of how a typical observer usually reads such images, Dondis (2000: 81) believes that we observe images much in the same way as we read books, from left to right, and we tend to value the upper part of the image. In that sense, we will follow along this sequence for the characters’ description.

The first element worth highlighting in the figure of Mary is her blue robe, which is associated with her image due to a cultural convention that has enabled the adornment on her head to differentiate her from the representations of ordinary women. The blue robe directly relates to the Ark of the Covenant, which by God’s orders was supposed to be covered with a piece of blue fabric every time it was transported over long distances. Since both of them - Mary and the Ark of the Covenant - bore the presence of God, this allusion was made linking the image of Mary to the blue robe. The symbolism of the robe also draws a parallel with the obedience of Israel in its fulfillment of the divine commandments, a trait that could also be attributed to Holy Mary.

As mentioned earlier, the intensity of the Virgin’s suffering at the feet of the cross was determined by the treaties of the Holy Office. According to Gonçalves (1990: 119), the Mother of God could not be made to suffer in a disproportionate manner because of the soundness of mind that was attributed to her. On the other hand, her suffering could not vanish altogether because of the love she had for her son. For those reasons, her facial features resemble an expression of serenity, devotion and piety and she does not weep like Mary Magdalene - though there is a tear rolling down her eyes - and she does not seem perplexed like Saint John. Because the work is quite dark, the details of the representation are difficult to inspect, but we can identify the halo above her head, representing her sanctity, and the position of her hands as a demonstration of intercession. Her face resembles that of a young woman, though she had a 33-year-old son, but Josefa’s intention of alluding to a gracious image in order to captivate her observers is understandable.

We suppose that John was put into the picture because he was set as the personification of the devotee who loves God. His symbolic role as the disciple whom Jesus loved the most evokes the possibility for the faithful to connect with Christ, and because of this one finds that out of the three characters, he is the only one who seems to be moving forward - an action that demonstrates a possible attempt to get closer to/touch his Savior.

His robe is colored in bright red and draws more attention than the blood that emanates from Christ. While Holy Mary and Mary Magdalene occupy half of the frame, Josefa granted Saint John the entirety of the other half, yet the artist portrays his halo as less luminous to demonstrate that he is inferior to Holy Mary. Saint John’s long hair is part of Josefa de Óbidos’ habitual style, who adorns in a womanlike manner all the elements that give her the opportunity to do so. Some tears can be seen in the perplexed face of Saint John as well as an expression of angst, exemplifying the way in which the faithful must act if he was faced with the possibility of losing his Savior.

Whereas Saint John could be personifying the God-fearing faithful, Mary Magdalene, who had previously been a prostitute and was forgiven by Jesus, personifies the faithful that is in need of mercy and thus of divine forgiveness. She is one of the characters who are able to express the devotion, penitence and the redemptive work of Jesus most earnestly. “Repentant, dramatic and lost in her love for Christ, she is one of the emblems of the Baroque catechetical church, a supreme exemplum of Catholicism’s endless willingness to welcome sinners” (Sobral 1991: 55).

Right next to Mary Magdalene there is a vial - a direct reference to the pint of perfume that she poured over Jesus’ feet and then wiped with her own hair days before his crucifixion. Such a demonstration of love is interpreted as an unconventional act of devotion, an absolute consecration of one’s being that is demonstrative of her gratitude for having her sins forgiven. In the painting, her bent posture as she clasps the cross’ feet with tears rolling down her face gives proof of her intensity. These deeds dramatize how the observer’s relationship to the divine ought to be like: intensity-driven, marked by devotion and an utter surrender of one’s soul. She doesn’t wear a robe, nor is there a halo over her head - such elements would have sanctified her. We presume that the painter’s intention was to illustrate to the faithful that all have access to Jesus, not only the Saints.

Once we analyze the sequence of the characters we have discussed, we find that Mary comes first, John comes second and Mary Magdalene comes third (note that in this painting we are not focusing on Jesus, who is the central figure). Furthermore, it has been observed that the nuances of suffering increase according to the level of corruptibility of the character that is being depicted, as if suffering was inversely proportionate to one’s level of sanctity.

This possible interpretation of the work is one example of an educational principle put forward by means of the (Baroque) aesthetic and the (biblical) narrative used in the painting, which does teach even though teaching may not have been its express aim; and it fulfills this role by providing the observer with meaning. As the religious goal of the Baroque was to persuade believers to live righteously and in accordance with the biblical narratives which were made accessible by way of the paintings, we believe in the validity of the exercise of conducting an analysis of the message conveyed through the work. To that end, one seeks to look beyond the evident aspects and search for those that are instilled in the painting, whose dramatic impetus has a directive potential.

Maravall (1997: 258) asserts that in this historical period the world was conceptualized as a clash between opposites, and that the Baroque lives at the center of these oppositions, amongst the different religious mindsets and the conflicts for economic or political sovereignty, to name a few examples. As attested by its nature, the Baroque lives in the midst of all the polarities that drive it to be a mediator between two rationalities, the result of the contradictions between laughter and weeping, the current state (corruptible) and the state that is wished for (incorruptible), thus providing the works with a sense of drama.

The dramatic impetus conveyed by the work is proportionate to the event that it depicts: the redemptive act of Christ is elementary for the Catholic worldview. The purposes imbued in the precepts of the Catholic Church are centered on the sacrifice of Jesus, which has granted to those who would come to believe in him the possibility of salvation. As has been pointed out earlier, salvation was the end that the faithful in seventeenth-century-Portugal would strive toward. And it was the king’s task to tend to it, with the Church’s collaboration.

The educational principles instilled in the narrative illustrated by the painting are not enigmatic, as seen in the previous paintings. Rather, they are clairvoyant: they sway the observer and elicit piety in him, as well as feelings of guilt and unworthiness. Mary, John and Mary Magdalene’s suffering around the cross serves as a model for how the faithful ought to respond to Jesus’ martyrdom. In this regard, Hatherly (1991: 73) claims that art used to appeal to “allegories and parables to describe the relationship of visible things with invisible, transcendent things.”

Although such a theme is portrayed quite often, one ought to consider that this painting calls the faithful’s attention as it was meant to be placed in church, an environment that is conducive to contemplation. Such an environment guides the faithful through an experience of fear and consequently to the experience of a dialectical reaction that leads to self-reflection and a change in their conduct. Biblical stories depicted by pictorial means work similarly to uttered sermons: their aim is to produce a reaction in the devotee’s reality. Since in that period the individual was both subject and faithful - spectrums which were not separated - art educated in a religious manner in order to perpetuate its own social situation.

Closing remarks

In light of this, we have found that in each work analyzed there are premises revealed whose purpose is illustrating a religious truth and that they do, after all, teach. Through the analysis, it has also been observed that even paintings of a decorative nature have much to contribute in the investigation of the time period in question; moreover, they may contain encrypted messages which reveal how artists expressed themselves. It has also been verified that most of the paintings are derived from engravings, which have greatly contributed to perpetuate the hegemonic principles, pictorial formulas and allegories of Catholicism, as well as the Baroque movement in a general sense. Lastly, we have found that the Baroque aesthetic, immersed in contrasts, exaggerations and paradoxes, persuades the faithful/subject to perform a re-evaluation of his own deeds in search of salvation, adhering to the educational principles advocated by the situation of the Catholic Reformation.

In conclusion, the Baroque was linked to a resonant attitude in its spectators, as the formal aspects of this movement have directive features that are meant to guide its observers. In that sense, we have based our reasoning on Saviani’s (2013: 43-44) understanding of the nature of education: because its aim is the furthering of man, this closely relates to the prevailing institutional objectives of seventeenth-century-Portugal. We argue that the Baroque has contributed for the education of seventeenth-century-man because it made it possible to promote in him the desired characteristics for his education. It aspired to propagate and preserve the Catholic faith, goals which were instilled in the individuals of the Seicento. Finally, when we analyze the works of Josefa de Óbidos, we see possible educational principles, especially of a religious sense.

REFERENCES

ARGAN, G. C. Imagem e persuasão. Ensaios sobre o Barroco. São Paulo/SP: Schwarcz, 2004. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, A. M. A imagem no ensino da arte. São Paulo - SP: Perspectiva, 2012. [ Links ]

BÍBLIA. Português. Bíblia de Jerusalém. São Paulo: Paulus, 2002. [ Links ]

DONDIS, D. Sintaxe da Linguagem Visual. São Paulo - SP: Martins Fontes, 2000. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, A. G. A educação no Portugal Barroco. In: STEPHANHOU, M.; BASTOS, M. H. C (Orgs.). História e memória da educação no Brasil. Vol I - Séculos XVI-XVIII. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2004. pp. 56-76. [ Links ]

GOMBRICH, E. H. A história da Arte; Álvaro Cabral. Rio de Janeiro - RJ: LTC, 2011. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, F. História da Arte: Iconografia e crítica. Lisboa. Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1990. [ Links ]

HATHERLY, A. As Misteriosas Portas da Ilusão. A propósito do Imaginário Piedoso em Sóror Maria do Céu e Josefa d’Óbidos. In: SERRÃO, V. Josefa de Óbidos e o Tempo Barroco. Lisboa, TLP - Instituto Português do Património Cultural, 1991, p. 71 a 85. [ Links ]

HATHERLY, A. Esperança e desejo: aspectos do pensamento utópico Barroco. In: Josefa d’Óbidos: uma flor pintada não é uma flor. Carcavelos: Theya, 2016. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, J. P. Ler e escrever no mundo rural do Antigo Regime. Um contributo para a história da alfabetização e da escolarização em Portugal, v. 4, p. 435-445, 1996. [ Links ]

MARAVALL, J. A. A cultura do Barroco. São Paulo - SP. Edusp, 1997. [ Links ]

NARITOMI, J. Herança Colonial, Instituições & Desenvolvimento: Um estudo sobre a desigualdade entre os municípios Brasileiros. 100 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Economia) - Pontifica Universidade Católica, Rio de Janeiro, 2007. [ Links ]

PAIVA, J. M. de. Igreja e educação no Brasil colonial. In: STEPHANHOU, M e BASTOS, M. H. C (Orgs.). História e memória da educação no Brasil. Vol I - Séculos XVI-XVIII. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2004. pp. 77-91. [ Links ]

SERRÃO, V. Josefa de Óbidos e o tempo Barroco. Lisboa: TLP - Instituto Português do Património Cultural, 1991. [ Links ]

SERRÃO, V. O essencial sobre Josefa d’Óbidos. Lisboa: INCM - Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 1985. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. Educação: do senso comum à consciência filosófica. São Paulo - SP. Autores Associados, 2013. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. Educação brasileira: estrutura e sistema. Campinas/SP. Autores Associados, 2012. [ Links ]

SOBRAL, L. M. Josefa d’Óbidos e as Gravuras: Problemas de Estilo e de Iconografia. In: SERRÃO, V. Josefa de Óbidos e o Tempo Barroco. Lisboa, TLP - Instituto Português do Património Cultural, 1991, p. 51 a 69. [ Links ]

2Serrão (1991: 45) points out that it was quite uncommon in the seventeenth century for a woman to work as a painter. However, there were some exceptions to the rule. In Spain, Luísa Roldán, Jesualda Sánchez and Josefa Sánchez can all be named as examples. In Flanders, Clara Peeters, Judith Leyster and Louise Miollon were all renowned artists. In Portugal, there were less prominent cases than Josefa de Óbidos, such as nuns Maria dos Anjos and Joana Baptista.

Received: August 14, 2021; Accepted: October 25, 2021

text in

text in