Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-127

Papers

The Student Youth and Authoritarianism in the Eyes of the Triângulo Mineiro Press (1964-1969)1

1Federal University of Uberlândia (Brazil). isauramelo66@gmail.com

2Federal University of Uberlândia (Brazil). sauloeber@gmail.com

The main objective of this article is to identify the most expressive representations aired by the Triângulo Mineiro press about the political actions and ideas existing among student youth in the face of the authoritarian in 1960s in Brazil (1964-1969) because they were marked by great political and sociocultural effervescence, close by monitored and recorded by newspapers across the country and, in this specific study, we focused in Cidade de Ituiutaba and Correio do Triângulo (Ituiutaba press); Correio de Uberlândia and Tribuna de Minas (Uberlândia press) and Correio Católico and Lavoura e Comércio (Uberaba press). There were more approximations than differences in the narrative produced by these vehicles of the press in relation to there presentations built around students, presented as citizens committed to "order and progress", and not to the "turmoil" that threatened the current status quo. Thus, newspapers acted between two poles ranging from immediate her acceptance to the authoritarian regime to the discreet challenge of their violent actions against students, building narratives and symbolisms of the local reality, aiming to manipulate and transform it according to the interests of the groups maintainers of this press.

Keywords: Student Youth; Press Representations; Civil-military dictatorship

Este artigo tem como principal objetivo identificar as representações mais expressivas veiculadas pela imprensa do Triângulo Mineiro sobre as ações e ideários políticos existentes entre a juventude estudantil frente ao autoritarismo da década de 1960. Privilegiou-se o recorte temporal dos anos iniciais da ditadura civil-militar no Brasil (1964-1969) por conta de terem sido marcados por grande efervescência política e sociocultural, acompanhada e registrada com proximidade pelos jornais de todo o país e, neste estudo em específico, enfocou-se os veículos Cidade de Ituiutaba e Correio do Triângulo (Ituiutaba); Correio de Uberlândia e Tribuna de Minas (Uberlândia) e Correio Católico e Lavoura e Comércio (Uberaba). Observaram-se mais aproximações do que diferenças na narrativa produzida por estes veículos em relação às representações construídas em torno dos estudantes, apresentados como cidadãos comprometidos com a “ordem e o progresso”, e não com a “baderna” que ameaçava o status quo vigente. Assim, os jornais atuaram entre dois polos indo da adesão imediata ao regime autoritário até a contestação discreta de suas ações violentas contra os estudantes, construindo narrativas e simbolismos da realidade local, visando manipulá-la e transformá-la de acordo com os interesses dos grupos mantenedores desta imprensa.

Palavras chaves: Juventude Estudantil; Representações de Imprensa; Ditadura civil-militar

El objetivo principal de este artículo es identificar lãs representaciones más expresivas que transmite la prensa del Triângulo Mineiro sobre lãs acciones e ideas políticas existentes entre La juventud estudiantil ante el autoritarismo de los años sesenta en Brasil (1964-1969) porque estuvieron marcados por una gran efervescencia política y sociocultural, monitoreados de cerca y registrados por periódicos de todo el país y, en este estudio específico, fueron enfocados los vehículos Cidade de Ituiutaba y Correio do Triângulo (Ituiutaba); Correio de Uberlândia y Tribuna de Minas (Uberlândia) y Correio Católico y Lavoura e Comercio (Uberaba). Hubo más aproximaciones que diferencias em la narrativa producida por estos vehículos em relación a las representaciones construídas en torno a los estudiantes, presentados como ciudadanos comprometidos com el “orden y progreso”, y no com la “confusión” que amenaza el statu quo actual. Así, los periódicos actuaron entre dos polos que van desde la adhesión in mediata al regimen autoritario hasta el discreta observación de sus acciones violentas contra los estudiantes, construyendo narrativas y simbolismos de la realidad local, com el objetivo de manipularla y transformarla según los intereses de los grupos mantenedores de esta prensa.

Palabras clave: Juventud Estudiantil; Representaciones de la prensa; Dictadura cívico-militar

Introduction

This paper discusses the representations about the actions and ideals concerning the secondary school and university students present in six newspapers published in the municipalities of Ituiutaba, Uberlândia and Uberaba in Minas Gerais in the period after the civil-military coup of 1964 until the end of the 1960s.2 Thus, it was chosen for study the printed papers Cidade de Ituiutaba and Correio do Triângulo published in Ituiutaba; Correio de Uberlândia and Tribuna de Minas, from Uberlândia; and Correio Católico and Lavoura e Comércio that circulated in Uberaba in this period.

It is noteworthy that these newspapers produced representations of the Triângulo Mineiro youth in large numbers at a time when students were projected as a source of resistance to the authoritarian government established in the country in 1964, presenting themselves in that context as one of the few channels that stood up to the civil-military dictatorship, through the actions of bodies such as the DCEs (Central Student Directories), the UEEs (State Student Unions) and the UNE (National Student Union), among others.

The reaction of the Brazilian student youth sought to oppose the civil-military coup that ended a democratic period of almost two decades after the end of Vargas' Estado Novo (1945-1964), starting a new prolonged authoritarian period based on a highly repressive apparatus towards civil society in general. In other words:

Authoritarianism also translated itself into an attempt to control and suffocate broad sectors of civil society, intervening in trade unions, repressing and closing institutions representing workers and students, extinguishing political parties, as well as excluding the popular sector and its allies from the political arena [...]....] The military state was characterized by increased intervention in the economic sphere, contributing decisively to the growth of the country's productive forces, under the aegis of a perverse process of capitalist development that combined economic growth with a brutal concentration of income (GERMANO, 2005, p.55-56).

The critical and protesting student movement became the main target of the dictatorship, among all the persecuted social categories. This fact can be verified by the large number of students arrested and killed. Between 1964 and 1974, representatives of the intellectualized social strata made up most of the opposition groups to the dictatorship, so that 57.8% of the total of 2,112 persons prosecuted by the Military Justice were young people, the majority of whom 51.8% were up to twenty-five years old, 81.7% of them belonging to the male gender (RIDENTI, 2010).

Even considering that the Brazilian student youth was one of the most expressive focuses of struggle against the civilian-military government, it cannot be understood as a homogeneous body committed in its entirety with the social transformations. There was a great diversity of political positions in the different student entities that emerged in this period, being located in various spectrums even those radically right-wing, such as the Communist Hunting Command (CCC).

It is from this pluralist perspective of the student movement that we sought to study it based on the representations conveyed by the Triângulo Mineiro newspapers, identifying the images-ideas produced in the relationship between the written press and this social group, presenting its contradictions and approximations in a context of great political unrest. It is clearly evident that the theme that associated the students to national politics disappears from the newspapers' pages as the authoritarian regime increases repression, so that the student movement gradually stops occupying the pages of the written press as a political agent.

In the data collection process of the research, the expression "student youth" was adopted to categorize the practices and ideals of the students present in the pages of the written press. Youth is understood as a phase of human development that comprises the period between adolescence and adulthood which is transformed by social changes that have occurred throughout history. This being marked by the diversity of social, cultural, gender and even regional conditions, among other elements (DAYRELL, 2001).

Besides the adoption of the theoretical instruments related to the debate around the concept of youth, we resorted to Roger Chartier (1990) and his concept of representations, which understands these as narrative and symbolic constructions of a given reality, but which would possess elements capable of transforming them, motivated by the interests of the groups which forge these representations:

The representations of the social world thus constructed, while aspiring to the universality of a diagnosis based on reason, are always determined by the interests of the groups that forge them. Hence, for each case, the necessary relationship of the discourses is uttered with the position of those who use them. The perceptions of the social are by no means neutral discourses: they produce strategies and practices (social, school, political) which tend to impose an authority at the expense of others, looked down upon by it, to legitimize a reforming project or to justify, for the individuals themselves, their choices and conducts (CHARTIER, 1990, p.17).

Therefore, we started from the understanding that the analysis of the press representations must be directly related to the study of the political and sociocultural context in which they were produced. When using periodical press as a source in historical researches, it is necessary to observe the multiplicity of socio-cultural elements present in the scenario where the journalistic reports were produced, as well as to try to be clear about the social role played by the newspaper under study (LUCA; MARTINS, 2006).

On this last aspect, it is important to situate, even if briefly, the context and main links of the newspapers, since as Chartier (1990) stated, the representations are forged from the interests of the groups that create them and seek means to convey them, in this specific study, the journalistic written press of the Triângulo Mineiro.

It is noteworthy that the press since its beginnings was marked by interests, deadlocks, divergences, ideologies and specific views of the world, man and society, which circulated by certain groups present in each historical moment, so that "If the text is the result of the conception of a particular elite, literate, it does not fully correspond to reality, but makes up an interpretation, a representation of reality, formulated at a particular time, under the influence of specific conceptions (GONÇALVES NETO, 2002, p. 205)".

From this perspective, it is important to know a little about newspapers, these factories that produce ideas in the social imaginary. In the table below, some information of the set of printed materials used in the research can be seen:

Table Written Press in the Municipalities of Ituiutaba, Uberaba and Uberlândia (1964-1969)

| Year | JOURNAL | FOUNDER/DIRECTOR | CHIEF EDITOR | HOME TOWN | RUNNING PERIOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897 | Correio Católico | Cônego Aurélio Elias de Sousa | Cônego Armênio Cruz | Uberaba | 1897 a 1972 |

| 1899 | Lavoura e Comércio | Antonio Garcia Adjunto | Quintiliano Jardim | Uberaba | 1899 a 2003 |

| 1938 | Correio de Uberlândia | José Honório Junqueira | Valdir Melgaço Barbosa | Uberlândia | 1938 a 2016 |

| 1959 | Correio do Triângulo | Benjamin Dias Barbosa | Jayme Gonzaga | Ituiutaba | 1959 a 1965 |

| 1966 | Cidade de Ituiutaba | Benjamin Dias Barbosa | Benjamin Dias Barbosa | Ituiutaba | 1966 a 1970 |

| 1966 | Tribuna de Minas | Cônego Antônio Afonso da Cunha | Antonio Pereira da Silva | Uberlândia | 1966 3 |

Source: Public Archives of the municipalities of Ituiutaba, Uberaba and Uberlândia, 2017.

Regarding the newspapers of Uberaba, the Correio Católico would have originated from another paper, the Jornal de Uberaba created on July 2, 1896 under the direction of Canon Aurélio Elias de Sousa, having several political collaborators, but after the 79th edition, it was transferred to the property of the local Dominican priests, receiving the name of Correio Católico, on October 10, 1897. Soon it began to be published daily under the command of Father Armenio Cruz. The creation of this newspaper, in the late nineteenth century, happened at a time of expansion of the Catholic press and ecclesiastical journalists, a movement encouraged after the publication of the Apostolic Letter by Pope Leo XIII on January 25, 1882, mobilizing the Catholic and ecclesiastical intellectuals to use newspapers as a vehicle for the conduction of religious moral principles (PONTES, 1976). The Catholic Courier was printed in black and white, published initially in weekly editions until it reached the daily format in the mid-1960s with six pages.

Lavoura e Comércio newspaper was also founded at the end of the 19th century, on 6July 1899, by the then Executive Agent of Uberaba Antonio Garcia Adjunto, which remained in this newspaper until 1903, when it was sold to Francisco Jardim, occupying the post of editor-in-chief his brother Quintiliano Jardim until his death in October 1966. As its title suggests, Lavoura e Comércio was founded to initially meet the needs of the farmers of the region. In the beginning, it had the objective of making a protest against the rural territorial tax considered abusive at the time. At the beginning of the 1950s, it published an average of five thousand six hundred copies, reaching the highest sales of the countryside newspapers (PONTES, 1976). It was printed in black and white, of daily publication and in six pages, being conveyed until the early 2000s.

If the Uberaba newspapers were linked to the tradition of ruralist and Catholic groups in Uberlândia the scenario was not different from the neighboring municipality. The Correio de Uberlândia was founded in 1938 by the rural producer from Ribeirão Preto, José Honório Junqueira, owner of seven other newspapers, who gave his son Luiz Nelson Junqueira responsibility for this newspaper, who soon hired Abelardo Teixeira as its editor-in-chief. Such periodicals, which represented the interests of social groups that were in power, effectively contributed to the consolidation of political and social imaginary of Uberlândia as a progressive municipality, which followed the developmentalism at the national level (ARAÚJO, 2007). It is noteworthy that this print since the 1940s had belonged to businessmen and politicians linked to UDN. Among its leaders were João Naves de Ávila, Nicomedes Alves dos Santos, Alexandrino Garcia and Valdir Melgaço Barbosa (FERNANDES, 2008). The latter took over the direction of the newspaper in 1952, remaining there during the years 1950 and 1960. In the period studied, the Correio de Uberlândia was published in black and white, every other day and also in six pages.

On May 13, 1966, in Uberlândia another catholic periodical was born as well as in the neighboring Uberaba, the Catholic Church sought to form opinion through the press founding the newspaper Tribuna de Minas, published three times a week, under the direction of Canon Antonio Afonso da Cunha and as editor Antonio Pereira da Silva. It is observed that the Catholics entered the narrative dispute in relation to the problems of that period, seeking to convey ideals that met their interests in local society through the written press.

Finally, the newspapers of Ituiutaba are presented, starting with Correio do Triângulo, which circulated between February 1959 and November 1965, weekly on six pages. It belonged to Benjamin Dias Barbosa, had as director and editor Jayme Gonzaga and as commercial director Joaquim Pires das Neves. On December 25, 1965, Benjamin Dias Barbosa started another venture creating the newspaper Cidade de Ituiutaba only changing the name of the previous newspaper and promoting some other changes, even so, it remained a weekly, printed on four pages until the year 1972, when it began to circulate bi-weekly, the following year it became tri-weekly, and daily in 1974, being sold in 1976. Benjamin Dias Barbosa as owner of these two newspapers that circulated in Ituiutaba worked to defend the interests of the ruralist elite of the municipality (FRANCO, 2014).

As can be seen, the newspaper owners were linked to the tradition of these municipalities, binding themselves to the rural and Catholic world of the region, they also fought for social prestige and the desire to share power. In this sense we corroborate the understanding of John Wirth (1982) in an analysis of the mining press after the Proclamation of the Republic:

The local press was another landmark of regionalism in Minas Gerais. In general, a small-town newspaper contained political news and commercial advertisements in a weekly edition of 500 copies. It was usually owned by the local political boss, whose dominance was disputed by a rival boss with his own press. It is clear that newspapers played a key role in local politics (WIRTH, 1982, p.131).

This logic that associated the written press and power lasted throughout the twentieth century, losing its strength with the emergence of other means of communication, however, still in the 1960s, the cut of this research, the newspapers maintained a large insertion in the political debate. This is evidenced in the analysis proposed here, which links the authoritarian regime to the change in the representation of student youth in the pages of the press.

The article is organized in three sections, besides the introduction and final considerations, namely: "The event of April 64 and the control of student youth in the eyes of the local press"; "Representations of student youth facing the authoritarianism of the years of lead" and "The national student movement and the "subversion" reported".

The April '64 event and the control of student youth in the eyes of the local press

In the days preceding the civil-military coup in April 1964, a movement self-titled "March of the Family with God for Freedom" spread across the country, especially in the large capitals. These demonstrations represented the impulse that was missing from the coup plotting spirit of the armed forces, which unleashed the movement supported by sectors of civil society that would culminate in the deposition of President João Goulart and the military takeover of power; the marches would continue until June of that year, giving legitimacy to the authoritarian government.

In the region of the Triângulo Mineiro it was no different, the press in this scenario gave prominence to the holding of such marches involving also the participation of a student portion, associated with conservative interests and in defense of the maintenance of the capitalist system. This movement was supported by the then governor of Minas Gerais, José de Magalhães Pinto, who mobilized the state troops and called for the cooperation of all miners in defense of the marches (SANFELICE, 1986).

The press celebrated this conservative social movement and highlighted the participation of students in the march in Uberlândia, as well as members of various sectors of the local civil society, as stated in its headline "Thousands of Uberlandia citizens in the March for Freedom" (Correio de Uberlândia, 05/04/1964):

PEOPLE'S PARTY. The monumental March with God for Freedom was an authentic and spontaneous people's party. But it was also a demonstration that Uberlândia is on the side of order, of democracy, in opposition to the atheist and disintegrations communism that destroys the Brazilian family. The samba schools of the people paraded, the students, the workers, the laborers, the intellectuals, the men of commerce and of the countryside, in short, all the social classes said 'present' to the march, symbolizing the 'no' to the totalitarianism that was tried to impose on free Brazil.

A newspaper from Uberlândia sought to create in the local imaginary the idea of unity around the fight against communism ("atheist and desegregationist"), annulling social differences and presenting after "the samba schools", "the students" in a clear movement that aimed to insert them as a category in the adhesion to April 1964.

In the municipality of Ituiutaba the "Victory March", according to the position defended by the press, took place on 3 April 1964, with the participation of about five thousand people in a march and mass in front of the local Mother Church, where the victory of the "Christian principles" over the so-called "communists" was celebrated.

3 April was a date that will be recorded in the history of Ituiutaba. No less than 5000 people participated in the grandiose victory parade, celebrating the change of government and the consequent defeat of communism that threatened the institutions and national sovereignty itself. Despite the almost improvisation, the parade sponsored by the Ituiutaba Student Union, was spectacular. Such enthusiasm and civic vibration had never been registered in our land. Prayers interspersed with hymns and cheers [...] On the improvised platform in the centre of 20th Street, several speakers were heard, among them Mr. Gotardo Soares Ferreira and Mr. Gersón Abrão, both law students [...] Ituiutaba vibrated in one of the largest public demonstrations ever held in our land. I rejoiced in the victory of democracy. It was a real Family March, with God for freedom (sic) (Correio do Triângulo, 07/04/1964).

This article also shows support for the military takeover of power through the march which, according to the newspaper's point of view, had the collaboration of a large part of society, led by the students represented by the "Ituiutaba Student Union" and by the "law academics". Through the reportage, the newspaper described the movement as the true act of civism, mixing "prayers interspersed with hymns and cheers".

In Uberaba, such a march commemorating the arrival of the military in power took place only on April 23, 1964, with a concentration in front of the Rui Barbosa Square. The organization of this event counted on the participation of ladies belonging to the local ruling classes and the Uberaba Commercial and Industrial Association.

The newspapers of Uberaba published a series of articles in support of the so-called "March with God for Democracy". The next day after the demonstration, Lavoura e Comércio newspaper published the headline "Uberaba lived the greatest civic hour of its history" (24/04/1964). In spite of the announced participation of several sectors of the Uberaba society in such an event, the local student class, differently from the other two municipalities, was not mentioned by the newspaper as one of the groups that collaborated and took part in this enterprise.

It is important to remember that right after João Goulart's deposition, most of the Brazilian press showed support to the military for taking power (BARBOSA, 2007), as did the Triângulo Mineiro newspapers.

In this context of adhesion of several sectors to the civil-military coup, students from Triângulo Mineiro were more closely observed by the written press. Since a considerable part of them had supported Lott and João Goulart in the elections to the presidency and vice-presidency of the Republic in 1960:

Source: Folha de Ituiutaba, 21/05/1960.

Figure 1 Article about the "Men's Student Committee for Lott

The students' organization in support of Lott indicated the alignment of ideals of part of the secondary students in the Triângulo Mineiro with the national4 student movement. In this period, the leaders of UNE, UBES and UME also showed support for Lott, with political tendencies closer to the progressive sectors (FRANCO, 2014).5 Soon the national student movement throughout the country was an immediate target of the repression instituted by the 1964 political regime, of conservative and authoritarian tendencies.

The UESU (Union of Secondary Students of Uberlândia) as well as the national student movement suffered the consequences of the authoritarianism imposed by the regime, as indicated by the local press:

The board of directors of the UESU, elected on March 29 could not take office, as we found out, on May 1, the date that had already been set, because some elements of its composition are under accusation of practicing communist ideas, contrary to the democratic regime established thanks to the revolutionary movement of April 1 [...] (Correio de Uberlândia, 13/04/1964).

On that occasion, the winning slate of elections for the year 1964 in a legal vote was prevented from taking office, its members were accused of being communists and demoralized before the local society, so that:

UESU suffered political interference, because of the leadership considered subversive and sympathetic to communism, but the movement did not need to be decimated, only replaced its leaders by others of political affinity with the new government (GUEDES, 2003, p.29).

After the students, considered "subversive", were prevented, another slate was elected and took office at the headquarters of the organ. This fact demonstrated the control of the students' manifestations in the region by the established conservative political forces, and the press had to collaborate with this perspective, which represented the desires of the dominant elites to deflate this movement.

The names of the secondary students who presented themselves as candidates for student representation went through a sort of screening so that they could direct the student unions in that locality. In this way, these bodies had to adapt to the new scenario of persecution of the students who engaged in opposition to the authoritarian political regime.

It was also frequent in this period the contact between the student entities in the region, as indicated in the column "Student Life" 6of the Correio do Triângulo of May 17th, 1964, which reported the visit of the president of the UEI (União Estudantil de Ituiutaba) to the headquarters of the UEU (União Estudantil de Uberaba):

On the 1st pp. the president of the U.E.I left for the neighboring city of Uberaba, where he went to deal with personal matters and those of the students of this city. He brought a message of solidarity and support to Marshal Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, entered into conversation with the current directors of the U.E.U. and brought us the honorable news of the victory of a person from Ituiutaba for the presidency of that entity [...] the names of that plate will be sent to Belo Horizonte, and there go through a screening process and then be sent back to Uberaba, not finding any compromising element will give the new leaders of the Uberaba Student Union (Correio do Triângulo, 17/05/1964).

The UEI and the UEU, as well as the UESU, suffered the impositions and restrictions established by the oppressive government, in an attempt to curb possible protests by secondary students against the new political directions, as occurred in the capitals.

In this repressive scenario, the student bodies were guided to organize their statutes according to the interests of the rightist forces. Even before the approval of the Suplicy de Lacerda Law, the UEI held an "Extraordinary General Assembly" that had the intention of elaborating a new constitution for the body, as demonstrated in the notice of convocation below:

STUDENT UNION OF ITUIUTABA

CONVOCATION

Extraordinary General Meeting

The president of the ITUIUTABA STUDENT UNION; in the act of his attributions, considering that the Statutes of the U.E.I are not in conditions to help both the Board of Directors, as well as the students affiliated to it in their activities, and using the prerogatives granted to him by Article 41 of Chapter VIII of the statutes of the entity, calls all registered students and those who are in good standing, in full use of their rights, to the Extraordinary General Assembly, which will be held on October 24 of this year, at 13.30 hours, in the Parish Hall Pius XII, at Rua 20 between avs. 5 and 7, in this city, where it will be discussed and submitted for approval the new CONSTITUTION of the Ituiutaba Student Union [...] Ituiutaba, October 1, 1964 [...] President of the U.E.I (sic) (Correio do Triângulo, 15/10/1964).

The Suplicy Law (no. 4.464 of 09/11/1964) proposed by the then minister of Education and Culture Flávio Suplicy de Lacerda provided for the dissolution of the State Unions of Students and the UNE establishing greater control over the student unions and student directories, these entities could not manifest themselves on issues of political order, thus, the regime sought to impose on the student entities new objectives and rules of operation (RIDENTI, 2010). The Castelo Branco government sought to limit even the cultural actions of the secondary students.

In high schools, groups may only be formed for civic, social and sporting purposes, whose activity shall be restricted to the limits established in the school regulations and shall always be assisted by a teacher (BRASIL, 1964).

In this way the civil-military dictatorship would establish a national climate of persecution of student leaders throughout the country, so that "[...] parallel to repression, the military governments and the social groups they represented engaged in an obsessive task, aiming at the control, manipulation or redefinition of the student movement" (SANFELICE, 1986, p.30).

In this sense, it is evident from the publications above that the triangulin press quickly sought to associate the local students to the movement in support of the authoritarian government that had been installed, not hesitating to expose the young students ("communists'') who placed themselves in opposition to the new regime. On the other hand, they celebrated the social conservative movement of the marches in their headlines, however they were defined in each newspaper: "Marcha pela Liberdade" (Correio de Uberlândia), "Marcha da Vitória'' (Correio do Triângulo), "Maior Hora Cívica" (Lavoura e Comércio), linking the marches to freedom, victory and civism.

Representations of student youth facing the authoritarianism of the years of lead

In April 1965, the academics of the Law Faculty of Uberlândia, on the occasion of the visit of President Marechal Castelo Branco to the city, took the opportunity to show "solidarity" and "support" for his government, demanding the immediate federalisation of this institution, as reported by the Correio de Uberlândia in the note "FDU students: they are with Castelo":

During the visit of Mal. Castelo Branco to Uberlândia, scheduled and confirmed for the day after tomorrow, the Academic Directory 21 de Abril, representative body of law school students, will deliver to the president a memorial which, among other things says: 'We are not just writing a motion of solidarity; we mortgage you a sincere vote of confidence, symbol of recognition and trust from the student body'. Next the memorial states that: 'the Uberlândia Law School, pioneer of university teaching in the city, headed by the illustrious and dynamic director Dr. Jacy de Assis, internationally renowned jurist, founded to defend the university ideals and the democratic postulates, expects from you immediate federalization, so that, united to the federal government, it can continue to monitor the government goals, so well traced in attendance to the true social norms - protection and support to the Brazilian people'. The manifesto will be signed by the university Públio Chaves, president of DA 21 de Abril (Correio de Uberlândia, 02/04/1965).

It is noted that the aforementioned newspaper emphasized firstly the "support" of the representatives of the "Diretório Acadêmico 21 de Abril" to the federal government, in the title of the article, and secondly revealed excerpts of the memorial produced by the students in favor of the federalization of the college. Thus, the newspapers expressed themselves more cautiously in order to escape censorship, even those with a more conservative profile.

In 1966, as a result of the persecution of the politicized student movement, rumors circulated that the UESU could be closed down due to the fact that the federal government had suspended the activities of the UNE and the UEE of Minas Gerais for six months, as previously discussed. The congresses held by the UEE of Minas Gerais in the municipalities of Uberaba and Uberlândia in 1965 addressed political themes that were accused of communist inspiration by the government's National Information Service (CUNHA, 2007).

The UESU board of directors immediately tried to provide clarifications to the population through the press, as it addressed the note "UESU Was Not Closed: Secundaristas Explain":

The UESU (Union of Secondary Students of Uberlândia) in a message sent to this newspaper warns all secondary students that, contrary to certain rumors spread that said that the federal government had closed the UESU, we only warn that it suspended the UEE (State Union of Students), the body that leads university students in Minas Gerais, for six months. We have not received any communication from the constituted authorities and we don't think that we will, because the UESU only looks after the welfare of the students, since its Statute forbids it to manifest itself in any way on national or international politics. The statement of the UESU thus undoes misunderstandings which claimed its closure and bears the signature of the young student Reinaldo da Silva Gomes. Secretary - general (sic) (Correio de Uberlândia, 08/07/1966).

In this way, the secondary students from Uberlandia demonstrated the fear as to the repression instituted, justifying the adequacy to the Suplicy Law, as to the denial of the political character of the entity in this period. This fact indicated the existence of persecution also against the student movement in the region, so that the students saw themselves in the duty of clarifying the society, using for this the privileged vehicle of the press.7

It is important to consider the fact that, in less than two years of military rule, the government was showing signs that it would not hold new elections as it had announced, so that the dictatorship would start to lose support from part of civil society and would move towards increasing repression against student-led protests. 8

According to Poerner (1995) the climax of the student rebellion was reached on 22 September 1966, defined as the National Day of Struggle against the Dictatorship. This was marked by the occurrence of marches moved by the theme "Organized people overthrow the dictatorship". The government reacted immediately to the student demonstrations and in the early morning of the 23rd occurred the famous "Massacre of Praia Vermelha", when hundreds of police officers invaded the University of Brazil, now the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Praia Vermelha Campus, and violently attacked about six hundred students.

Such event generated even more tension between the student movement and the government, multiplying the actions around the country: "Starting from the repression of a small student demonstration in Belo Horizonte, a cycle of protests against police violence grew like a snowball, which provoked new repressive acts generating other demonstrations against repression" (MARTINS FILHO, 1998, p.17). In this context the press all over the country gave prominence to the student agitation, since, still according to Martins Filho (1998), for the first time the military government did not hesitate to repress severely the manifestations of the young people belonging to the middle class.9

Such events also had repercussions on the protests of the Central Directory of Students of Uberaba, which considered the press to be the privileged vehicle for the dissemination of the position of the student representatives on the situation of repression experienced by the student movement all over the country. Soon the university students from Uberaba aligned to the interests defended by the UNE promoted a general meeting among all the Academic Centers to discuss the best way to protest against the atrocities experienced in the national sphere. These events always had space in the Catholic Courier, as the note of September 19, 1966: "Students decide today: strike or protest march".

From this assembly, the DCE of Uberaba, with the support of the Academic Centers, decided to hold a general strike as a sign of protest against the violence suffered by students in several Brazilian capitals. Fact communicated in two newspapers of the city: "To the Students of the Law College of the Triângulo Mineiro" (Correio Católico, 20/09/1966); and "Diretório Central dos Estudantes de Uberaba - esclarecimentos" (Lavoura e Comércio, 21/09/1966):

Source: Lavoura e Comércio, 21/09/1966.

Figure 2: Note with clarification from the Uberaba DCE to the local population.

It is observed by this note that the newspapers, despite opening space to the students, maintained some caution, this publication of the DCE was inserted in the interior of the periodical, highlighting the expression "On Request" that reinforced the authorship of the communiqué, trying to exempt the editorial staff of the newspaper. The students were also cautious, when they called for the deflagration of the "strike for 48 hours" in repudiation of the violence against their category, reinforcing that the movement was peaceful and democratic. Even so, the note demonstrated the engagement of the youth in denouncing to the local society the acts of violence of the oppressive government, especially against the students.

The strike of university students in the Triângulo Mineiro occurred as a reflection of a process of discussion at the national level of the decisions established by the UNE on September 18, 1966, which decreed a general strike of academics throughout the country as a result of successive attacks by the government to the protesting student movement. Through the clarification of the students from Uberaba to the local population, it was possible to evidence the contact with the national student movement in a moment of strong tensions.

The fact that the manifestos and the clarifications made by the students to the local population never appeared on the front pages of the newspapers, being published in very small notes on the last pages, certainly as a result of the censorship and repression scenario experienced at the time, should be stressed again.

Thus, it was sought to pay attention to the materiality of the printed content. According to Chartier (1991), the form with which the text reaches its reader determines the author's intentions and the imposition of the workshop. In this way, it can be observed that the articles considered more "delicate" in relation to the political context, intentionally presented a location that made it difficult to read them.

Another element that was noteworthy was the absence of photographs of students in their protests, campaigns and political demonstrations. This indicated the intention to protect the image of the young students of the region, keeping them away from polemic manifestations and at the same time not promoting public figures without counterparts.

In relation to such protests on the part of the student movement, the newspaper Lavoura e Comércio pronounced the defense of Marshal Humberto Castelo Branco by means of the headline "The university students of Uberaba return to classes" (Lavoura e Comércio, 22/09/1966):

The head of government Mal. Humberto Castelo Branco, recommended that the authorities concerned and principally the State governors redouble their efforts to moderate the repression of students during demonstrations. The Head of the nation stated that this repression should be as mild as possible, and should only serve to maintain order [...].

The position of that newspaper in publishing the speech of the then president, indicated its intention not to commit itself in publications contrary to the purposes of the government, seeking to assume a certain exemption of positions. Besides, it presented a message that constituted at the same time a defense of the authoritarian government, representing also a message to the students, especially to the rioters that should be the target of repression.

The Uberlândia university students also published their protest in the Tribuna de Minas and, as in Uberaba, declared a general strike in solidarity with the aggressions suffered by the student movement on a national level, under the headline "Uberlândia university students on strike":

The Manifesto addressed to the university students and to the people in general considers the following items: 'Whereas 1) - our colleagues have suffered unjust oppression in various states of Brazil. 2) - we cannot remain insensitive to the struggle undertaken by our colleagues in defense of our inalienable rights. 3) - The university students of Uberlândia have always been guided by moderation in all student movements. 4) - This manifesto is addressed to the real students and not to those who take advantage of the present situation to agitate the nation. 5) - We will continue in constant vigilance for the autonomy of our class and in the supreme struggle for the causes and interests of our university colleagues. WE RESOLVE: we declare a strike from today until the 26th (inclusive) of the current month in solidarity with our colleagues from all over Brazil' (sic) (Tribuna de Minas, 25/09/1966).

It is evident the commitment of these young people with the defense of the interests defended by the students all over the country. On the other hand, they defended moderation within the student movement, denouncing the excess of agitation provoked by "false students". Besides, it is noted that when the violence reached the middle and upper class youth, these newspapers began to give more prominence to these occurrences.

Below the student protest, the Tribuna de Minas newspaper published, as did Lavoura e Comércio, Castelo Branco's speech in relation to the latest events taking place throughout the country, as well as the defense of the uberland students, it is noted:

Castelo Branco calls for calm. In a previous statement, President Castelo Branco asked the authorities to be more accommodating to the students, without, however, allowing them to carry out abuses [...] The students from Uberland seemed to want to maintain an atmosphere of peace, as had always occurred in their participation (sic) (Tribuna de Minas, 25/09/1966).

It can be observed that the press, when publishing the student strikes in the region, took care to unaccountability of the head of the federal government in relation to the increase of repression to the student movement in the capitals. Besides, it tried to format the action of the local students in the scenario of violence against the students.

It is worth highlighting the fact that the mobilization of the university movement directed by the UNE after the civil-military coup was driven by a series of factors related to the educational and economic policy implemented by this government.

The problem of the surplus, the lack of funds, the authoritarian modernization of teaching, waved with the MEC-USAID agreements and with other governmental initiatives, the archaism of the university institutions prior to 1964, the economic crisis generated by the wage squeeze and the narrowing of job opportunities even for the graduates, the so-called "crisis of the bourgeois culture", the repressive policy of the dictatorship against the students and their entities (RIDENTI, 2010, p.125).

Such elements highlighted by Ridenti (2010) contributed to create a great student discontent and to resume the struggle of university students for educational reforms that would enable social ascension via education. In this scenario, the MEC-USAID agreements were seen as a clear distortion of the ideals pursued by these students.

From 1966 onwards, North American domination of Brazilian education intensified through the MEC-USAID Agreements, which aimed to transfer to Brazil the model and university standards of the United States.

At this juncture, the academics mobilized against these agreements throughout the country, so that constant marches and demonstrations began to take place in order to defend the specificities and interests of Brazilian university students. 10

In Uberaba it was no different, the DCE immediately tried to denounce and protest against the influence of North American imperialism in higher education and in all of Brazilian society through the Correio Católico in the June 1st 1967 edition, in the following manifesto, published in a small note inside the newspaper:

Central Students Directory Uberaba

The following points emerge from the discussions:

1) The Agreement with the USA, through USAID, maintains with the University of Brasilia, remembering that the Americans control the whole library and that the books that say anything about the Brazilian reality are being replaced by American books;

2) The repudiation of the students of Brasilia for the Accord and the memory of the beatings they suffered when they protested against the visit of the American Ambassador to the University of Brasilia;

3) The attempt by North American Imperialism to implant, through the Accords, a new form of culture, it was recalled that: "CULTURAL DOMINATION IS THE WORST OF THE DOMINATION THAT A PEOPLE CAN SUFFER" [...]

Uberaba, 31 May 1967

Thank you with cordials

UNIVERSITY GREETINGS

The Commission.

Such protests of the university students of Uberaba presented a critical, politicized and contestatory character, revealing the articulation of interests with the student movement in the capitals of the whole country, in struggle against the North-American domination of Brazilian education and culture. Besides, it showed the repudiation of these students against the violence exercised by the authoritarian government against politicized demonstrations, specifically at the University of Brasília. 11

Thus, we agree with the understanding that young people presented themselves to Brazilian society at various moments in history up to the end of the 1960s, as important agents supporting resistance practices against oppression and unifying projects of nationality (CACCIA-BAVA; COSTA, 2004).

The publication of the manifestos through the newspapers allows us to understand that the press was seen by the students as an important means of communication and dissemination of information in society. However, it is reinforced once more that such themes were published with caution by these newspapers, always occupying small notes in the footnotes and never on the front pages, expressing not only the fear of censorship, but also a way to protect the students, by minimizing their demands in the pages of the periodical.

The issue of surplus vacancies in the universities, as well as at a national level, worried the academics of the Uberaba Medical School. As a result, strikes were organized by the students between 1966 and 1967, demanding more funding and vacancies for the institution.

The article "Strike of medical students brings the Minister of Education to Uberaba" (Lavoura e Comércio, 18/08/1966), indicated the coming of the then minister Raimundo Muniz Aragão to Uberaba in August 1966. On that occasion, the same, according to the article, would have approved the allocation of five hundred million cruzeiros for the following year, which should be paid in several installments, for the Triângulo Mineiro Medical School, as a result of the claims made by the Gaspar Vianna Academic Center of that institution.

In 1967, several strikes occurred again in the Faculty of Medicine, due to the non-compliance of the MEC in relation to the approved funds and the impossibility of opening vacancies for the surplus. Soon the university committee went to Brasilia to deal with Minister Tarso Dutra, receiving the support of the Federation of University Students of Brasilia (FEUB), according to the article "MED strike still continues" (Correio Católico, 19/04/1967).

These occurrences indicated the struggle and unity of Brazilian university students in this period in search of improvements for their institutions, given that the period was marked by university crises:

The student movements of the 1960s, depending on when and where they took place, were diverse expressions and modulations of these crises, through demands such as the politicization of university life, proposals for co-management and self-management, 'ideas of student power' and practices of a critical university. As well as passing through the crisis of hegemony of the university institution, they expressed the desire to expand the right to university life, concomitantly with the denunciation of its functionalization, but then moved on from the defense of its autonomy in the face of political and economic powers to the denunciation of its false isolation, defending a progressive social participation by the university (GROPPO, 2006, p.32).

In this sense it is understood that even though the university movement of Uberaba, in the 1960s, has experienced the so-called "crisis of hegemony" of the university, generating tension points in the relations with the State, its actions were minimized in the pages of local newspapers that served the interests of maintaining the local status quo, linked to the rural and Catholic tradition and that wanted the maintenance of order, keeping away any idea different from the Christian values as the "atheist communism". In the other triangulin newspapers, the form of representation of the student youth actions did not diverge greatly from the model of the Uberaba press.

The national student movement and the reported "subversion

The UNE (National Union of Students) was the main target of the civil-military government and the press played an important role in the disqualification of this body, with the newspapers of the region conveying such derogatory representation with great emphasis after 1964. In this scenario, a true crusade was established in order to dismantle the national student movement, represented by the UNE. The narrative established was that this entity would shelter a great part of the communist youth that would negatively influence the other student bodies.

Many news articles published in the Triângulo Mineiro reproduced articles with such content, as can be read in one of the Ituiutaba newspapers, positioning itself contrary to the actions undertaken by the UNE that would be infiltrated by communists, see the article entitled "Os comunistas e a UNE" (The communists and the UNE):

COMMUNIST INFILTRATION - For years - and notably during the government of Mr João Goulart - the trade unions and student bodies have suffered the effects of communist infiltration. In their eagerness to conquer one more satellite, the members of the Brazilian branch of the international CP have tried to intervene in the classes most susceptible to organization - the workers and students [...] The countries of the iron curtain have also contributed to the demoralization of our youth [...] The political task of the student as such is too similar to that of the worker [...] When the student tries to shake up the society in which he lives, the movement suffers a process of deterioration, becomes corrupted, speaks for itself or leads the country itself to chaos! (Triangle Post Office, 09/08/1964).

It is verified that the student organizations, in general, became linked to the deposed government of João Goulart, demonized by the closeness to the trade unions and to the students, that would have demoralized both, as it had occurred with the "iron curtain countries". It is important to stress that we did not find in this research any journalistic article that demonstrated the explicit apology to communism on the part of the student entities.

Thus, the constructed narrative was simple: when the students started to contest the order, disturbing the flow of society, it was a sign that their leaderships had been corrupted and could lead the country to chaos, which would demand, therefore, firmness in the sanitation process of these bodies, starting with the UNE. The same vigilance that was established in relation to the unions should be extended to these entities, this was the discourse defended by the newspapers of the region.

The XXVIII UNE Congress, promoted in the capital of the State of Minas Gerais on July 28, 1966, yielded several criticisms of Lavoura e Comércio, even before it took place.12 Among these were the articles: "Congresso de Estudante não será realizado" (Student Congress will not take place) (26/07/1966); and "Congresso da UNE visa a dissolução da estrutura social" (UNE Congress seeks to dissolve the social structure) (27/07/1966):

BELO HORIZONTE - 27 (SE) - The Secretary of Public Security of the State of Minas Gerais is still in opposition to the holding of the National Congress of Students of the UNE, a congress which is scheduled, in principle, to take place from the 28th. The authorities affirmed that the congress would be a starting point for a national movement to dissolve the social structure (Lavoura e Comércio, 27/07/1966).

The emphasis on denying the prohibition of such an event indicated the articulation of the newspaper with the political interests of the groups that were in power at the beginning of the authoritarian regime, which feared any manifestation that went against the maintenance of the prevailing social structure.

After the UNE Congress was held, the same newspaper published, in a partial way, the result of such an event, reporting the detention of dozens of university students by DOPS, in the article "Enquadrados na Lei de Segurança 42 estudantes" (Lavoura e Comércio, 09/09/1966). In Belo Horizonte, the Dominican priests were accused of breaking the law, by protecting the students who took part in the movement, being considered to be defying the government, in the article "IPM in the students' congress" (Lavoura e Comércio, 02/08/1966). Such articles divulged by part of the newspapers of the region in relation to the actions of the student movement in the capitals, originated from the great national press, which participated in the consortium that supported the civil-military dictatorship (KUSHNIR, 2004). 13

Thus, Lavoura e Comércio sought at the same time to condemn the national student leaders and to keep the local youth away from subversion and from the "communist danger", reinforcing the Christian values and principles of the local population. As can be highlighted in the article "Castelo does not want student agitation" (Lavoura e Comércio, 13/09/1966), which stated that President Marechal Castelo Branco had met the director of the National Intelligence Service (SNI) and the ministers of Education and Justice, in order to seek "solutions" to the "student crisis".

In 1967, the narrative of Lavoura e Comércio continued to position itself in the criminalization of the national student movement, giving prominence to articles that indicated the scenario of persecution: "Students and union leaders the next cassados" (16/02/1967); "DOPS and SNI arrest students" (27/02/1967); "Student Congress will not be allowed (26/06/1967); "UNE Congress will not be held" (06/07/1967); "Students accused of guerrillas" (18/07/1967); "DOPS arrests student leader" (01/08/1967). All these emphasized the condition of student protesters as one of the main enemies of the established power.

The Correio do Triângulo also circulated in the micro-region of the Pontal do Triângulo Mineiro articles that repudiated the student participation in the political life of the country, severely criticizing the UNE, considered as a subversive entity and above all "demoralizing of youth". In this sense, the text "The UNE and Subversion" stands out:

If anyone of extraordinary good faith still had any doubt about the subversive character of the UNE, dominated by youth intoxicated by exotic ideologies, exploited and guided by foreign headquarters located outside the country, certainly he will now be aware of the true purposes of this clandestine and illegal organization [...] Instead of spending his life repeating slogans fabricated abroad, the Brazilian student should fundamentally fulfill his mission: to study. He should not forget, after all, that public schools are funded by the money of the people, by the money collected in taxes. The student who makes agitation and does not study steals from the people and becomes privileged (sic) (Correio do Triângulo, 14/10/1967).

The article above shows the defense of a conservative society, where the new generation would have to limit itself to the walls of the educational institutions, adapting to the world by means of education; the critical posture should be avoided because it went against the interests of the government then in force. In this sense, the representatives of the UNE were considered real criminals, accused of being alienated to foreign ideologies with a communist bias and of illegally taking advantage of public money. Besides, it was emphasized that the students should have the sole function of studying, and that those who participated in demonstrations would not be fulfilling their duty. In short, such publication ended up inciting the public opinion to rebel against the students who were politicized through their experience in the student movement, especially the public institutions funded by the people, who would not want to see their taxes paying for privileges and social agitation.

It was possible to see that between 1967 and 1968, the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper from Uberaba and the Tribuna de Minas newspaper from Uberlândia assumed a prominent position in the press of the region, for promoting the disparaging representation of the UNE and its leaderships, as it was possible to see due to the large number of articles published in this period that demoralized these students.

In May 1968 the Tribuna de Minas published the note "Estudantes Terroristas Prêsos" (Minas Gerais Tribune), discussing the arrest of one hundred and fifty-four students of the Faculty of Medicine in Belo Horizonte by the military police and the DOPS, under the penalty of tear gas bombs and truncheons. They were accused of having taken twenty-one professors and the director of the institution hostage.14

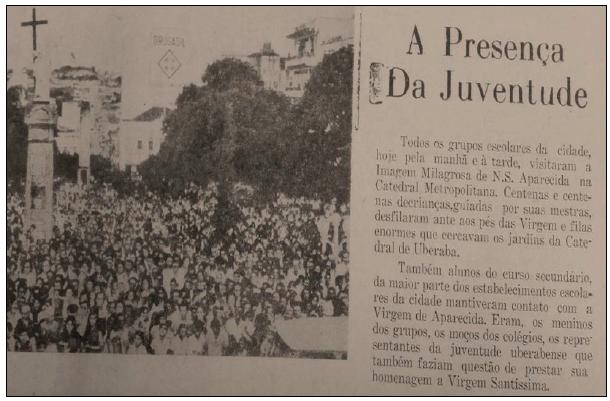

While the dictatorship used the monopoly of force to convince the students to join the regime or at least to shut up, the local newspapers tried to reinforce the representation of the youth as the Christian faithful, as can be seen in the following image, one of the few records that focused on this new movement of masses in which the student youth was constituted during the 1950s and 1960s:

Source: Catholic Post, 14/03/1968.

Figure 3: News about "The Presence of Youth" in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Uberaba

According to the article, the expressive participation of primary and secondary students in the popular catholic celebrations in Uberaba was highlighted. Since it highlighted the involvement of "all" the school groups and most of the local secondary schools. Thus, the Correio Católico was one of the main vehicles of the press to forge the image of the students linked to the Catholic faith, an amorphous mass at the foot of the cross in communion with the "Blessed Virgin", this should be the only possibility of organic action of this social group united by the Catholic Church.

The representations conveyed by the newspapers that debated the youth disappeared from the pages of the press, especially with the decree of AI-5, there was a drop in the number of news published in relation to the national and regional student movement, with the intensification of repression, also in relation to the press organs. After this act, there followed arrests, torture, kidnappings, exile and assassinations of student leaders, trade unions, intellectuals and journalists. Therefore, the discussion on the student demonstrations of political nature contesting the interests of the authoritarian government disappeared from the pages of the triangular newspapers, from 1969 onwards.

Final considerations

In this concluding space, it is necessary to understand that the arrival of the military to power was supported by several sectors of society, especially the economic elites and also intellectuals who largely controlled the narrative present in the written press, so that the well-known "Marches of the Family with God for Freedom'' won the showcase of most Brazilian newspapers, also in the Triângulo Mineiro, as we saw before. The result of that, as of April 1964, was the construction of the idea that the student entities should be "sanitized", silencing the critical spirit of their leaderships, thus, the newspapers disseminated such persecution actions to members of the triangulin student movement, especially those directed to the largest group, which were the high school students represented by the UEI, UESU and UEU, when they were forced to adapt to the requirements imposed by the repressive legislation of the dictatorial regime.

The greatest source of resistance to the authoritarian regime was located in the student bodies linked to higher education, a reflection of the national scenario in the Triângulo Mineiro. When the violence against the students increased, the newspapers started to report such arbitrary acts, such as the denunciations and the protests practiced by the DCE of Uberaba and part of the university students in Uberlândia. Another fact registered by the newspapers was the repudiation of the MEC-USAID agreements, mainly published by the Correio Católico, a press vehicle which distinguished itself from the other newspapers of the region, clearly supporting the students and their demands after almost two years of dictatorship, but even if it did not present the militant student as a subversive, it presented him as a subject that needed to be tutored, a reflection of the approximation between the national management of the UNE and progressive sectors of the Catholic Church, since 1961.

In general, the tension between students and government was quite present in the newspapers' pages, especially after December 1968 (AI-5), when there was the worsening of repression and violence against the young students' demonstrations and consequently the disarticulation of their political claims. Thus, gradually, the newspapers stopped reporting the students' actions as active political agents, prevailing the idea that "students should study".

The negative representation was much more linked to the national student movement (UNE) when compared to the image of the students of the region, since the local students and their families participated actively in the life of the newspapers, either as readers or advertisers. Thus, the media of the region, in their majority, circulated representations that incited the control of the youth in relation to the distancing of communist ideas and at the same time to promote their tutelage by bringing them closer to Christian values, even if these were not a reality present in all the student sectors, and of the scenario of violence experienced by the national movement in the capitals.

Based on the perspective defended by Chartier (2002), that the representations are never neutral discourses, being able to generate adherence and submission, it is generally considered that the representations of the press in the region about the students' political mobilizations during the 1950s and 1960s contributed to the circulation of an imaginary among the local society that valued the young compromised with the interests of the groups that were in power. This is due to the fact that the student movement gained space in the newspapers in this period, so they should be represented as citizens committed to the "order and progress" of the country, and not with the rioting and the threat to the status quo.

REFERENCES

BARBOSA, Marinalva. História Cultural da Imprensa: Brasil, 1900-2000. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad, 2007. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei Nº 4.464, de 9 de Novembro de 1964. Disponível em: www.gedm.ifcs.ufrj.br/upload/legislacao/357.pdf. Acesso em 23 jul. 2019. [ Links ]

CACCIA-BAVA, Augusto; COSTA, Dora Isabel da. O lugar dos jovens na história brasileira. In: CACCIA-BAVA, Augusto, PÀMPOLS, CarlesFeixa e CANGAS, Yanko González (orgs.). Jovens na América Latina. São Paulo: Escrituras Editora, 2004. [ Links ]

CARMO, Paulo Sérgio do. Culturas da rebeldia: a juventude em questão. 3. ed. São Paulo: Editora SENAC, 2010. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A beira da falésia: a história entre incertezas e inquietude. Tradução Patrícia Chittoni Ramos. Porto Alegre: Ed. Universidade/UFRGS, 2002. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A História Cultural: entre práticas e representações. Rio de Janeiro; Lisboa; Bertrand Brasil: Difel, 1990. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. O mundo como representação. Estudos Avançados, vol.5, n.11, São Paulo: USP, jan-abr/1991, p. 171-191. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40141991000100010 [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antônio. A universidade reformanda: o golpe de 1964 e a modernização do ensino superior. 2. ed. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7476/9788539304561 [ Links ]

DAYRELL, Juarez. A música entra em cena: o rap e o funk na socialização da juventude em Belo Horizonte. Tese de doutorado. São Paulo: Faculdade de Educação, 2001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022002000100009 [ Links ]

FICO, Carlos. Além do golpe: versões e controvérsias sobre 1964 e a Ditadura Militar. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-01882004000100003 [ Links ]

FRANCO, Isaura Melo. Estudantes tijucanos em cena: história de suas organizações políticas e culturais (Ituiutaba-MG, 1952-1968). Dissertação de Mestrado. Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 2014, 187 p. [ Links ]

GERMANO, José Willington. Estado Militar e educação no Brasil. 4. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2005. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES NETO, Wenceslau. Imprensa, civilização e educação. In: ARAUJO, José Carlos Souza; e GATTI Jr., Décio (orgs.). Novos temas em história da educação no Brasil. Instituições escolares e educação na imprensa. Uberlândia: EDUFU; Campinas: Autores Associados, 2002. [ Links ]

GROPPO, Luís Antonio. Autogestão, universidade e movimento estudantil. Campinas-SP: Autores Associados, 2006. [ Links ]

GUEDES, Nilson Humberto. Uberlândia - as facetas políticas entre governos militares e poder público local nos dois primeiros anos de pós-1964. Monografia apresentada ao Curso de Graduação em História, do Instituto de História da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 2003,68 p. [ Links ]

HOLLANDA, Heloísa. B. e GONÇALVES, Marcos A. Cultura e participação nos anos 60. (Coleção Tudo é História: 41) 1. ed. (1982), 1ª reimpressão, São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1999. [ Links ]

KUSHNIR, Beatriz. Cães de guarda: entre jornalistas e censores. In: REIS, Daniel Aarão et. al. (orgs).O golpe e a ditadura militar quarenta anos depois (1964-2004). Bauru-SP; Edusc, 2004. [ Links ]

LUCA, Tânia Regina; MARTINS, Ana Luísa. Imprensa e cidade. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7476/9788539303168 [ Links ]

MARTINS FILHO, João Roberto. Os estudantes nas ruas, de Goulart a Collor. In: MARTINS FILHO, João Roberto. 1968 faz trinta anos. Campinas-SP: Editora da Universidade de São Carlos, 1998. [ Links ]

POERNER, Artur José. O poder jovem. História da participação política dos estudantes brasileiros. 24. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1995. [ Links ]

PONTES, Hildebrando de Araújo. Cem anos de imprensa. In: Revista Convergência. Uberaba-MG, 1976, ano VI, nº 7, p. 123-132. [ Links ]

RIDENTI, Marcelo. O fantasma da revolução brasileira. 2º ed. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2010. [ Links ]

SANFELICE, José Luis. Movimento estudantil: a UNE na resistência ao golpe de 64. São Paulo: Cortez: Autores Associados, 1986. [ Links ]

SKIDMORE, Thomas. Brasil: de Getúlio Vargas a Castelo Branco (1930- 1964). 5.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1976. [ Links ]

WIRTH, John. D. O Fiel da Balança: Minas Gerais na Federação Brasileira 1889-1937. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1982. [ Links ]

2The article stems from doctoral research entitled "A Juventude Estudantil pelo Olhar dos Jornais do Triângulo Mineiro: Entre a tutela e a subversão (décadas de 1950 e 1960)" defended under the PPGED-UFU (Line of History and Historiography of Education), in 2020.

3No reliable information was found about the year when the activities of the newspaper Tribuna de Minas ended. However, it is known that it circulated during the period from 1966 to 1969, which is of interest to the present study.

4On the occasion of the last presidential election before the civil-military coup of 1964, a group of secondary and university students from Uberlândia also formed the Nationalist Student Committee Pro Lott-Jango-Tancredo, in support of the candidates of Marechal Henrique Teixeira Lott for the presidency of the Republic, launched by the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the Brazilian Labor Party (PTB), João Goulart for the vice-presidency through the PTB and Tancredo Neves for governor of Minas by the PSD. "Lott exercised an a priori attraction on left-wing nationalists, in the defense of several nationalist causes - the concession of the right to vote to illiterates and the restriction of profit remittances from foreign firms abroad" (SKIDMORE, 1976, p.234).

5On the other hand, the representatives of the Central Students' Directory of Uberaba showed support for the candidacy of Fernando Ferrari for vice-presidency of the Republic, launched by the Christian Democratic Party (PDC) and the Renewing Labour Movement, as indicated in the political mural of the Correio Católico, "Founded the Pro-Ferrari Directory" (06/05/1960). In that 1960 election, Jânio Quadros was elected president by the National Labour Party (PTN) supported by the UDN and João Goulart elected vice-president by the PTB. The interest of the triangulin students for politics at that moment demonstrated a movement of politicization of high school and university students, following the process of engagement of young people in the student movement at the national level.

6This column represented a way for the Correio do Triângulo to disseminate and pass judgment on the actions of the local and national student movement, contributing to the persecution of students who dared to contest the interests of the civil-military political regime.

7On the other hand, it is possible to observe that the political activism of young people reached a relevant level in the 1950s and 1960s, so that the destinies of these bodies came to be controlled more closely. Soon it was important to refute rumors related to these bodies and to local student events.

8After the decree of Institutional Act number 2 (AI-2), in 1965, which suppressed the populist parties and determined that the presidential elections should be indirect, the resistance in Brazil also grew through denunciations of torture and the path that the military regime began to adopt (FICO, 2004).

9Poerner (1995, p. 204) states that: "The dictatorship's thinking regarding the university and the students was summed up in a 'solution': the 'shock treatment' [...] to 'put an end to subversion'. It was a matter [...] of expelling the demon of patriotic rebellion from those young bodies, replacing it by the angel of subordination to anti national interests. For this objective [...] to be achieved [...] everything was worthwhile: suspend, expel, arrest and torture students; fire professors; invade faculties; intervene, by police, in student bodies; forbid any kind of meeting or student assembly; put an end to student participation in the collegiate organs of university administration; decree the illegality of the UNE, of the student nations in the States and of the academic directories; destroy the University of Brasilia; put a stop, in short, to the process of renewal of the student movement and of the university in our country [...]".

10"The movement against the MEC-USAID Agreements reached its climax when the Minister of Education himself, Tarso Dutra, although claiming not to know the texts, committed himself to review them, 'in all the points considered inconvenient to the interests of Brazil'. On April 26, 1967, before the Commission on Education of the Chamber of Deputies, when asked if he had read them, he said: 'No, I have not read, but when I do, if it is harmful to the national interest, I will modify it' (Jornal do Brasil, April 30, 1967 apud POERNER, 1995, p. 228).

11This DCE manifesto also expressed in the highlighted phrase, related to the cultural domination, the anti-Americanism, which ended up losing strength with the counterculture movement coming from the United States, as of 1968. It was a scenario in which many young Brazilians lived the impact marked by a conjuncture of conflicts generated not only in the peripheral societies, receiving influences from the North-American youth that protested against the Vietnam War and gave way to a pacifist resistance movement (HOLLANDA; GONÇALVES, 1999).

12The reasons for holding this Congress were not highlighted by Lavoura e Comércio. Among these was the fight for the revocation of the MEC-USAID agreement, in defense of the federal universities and public schools, for literacy for all, for a quality secondary education and for the revocation of Lacerda's Suplicy Law (SANFELICE, 1986).

13Part of the mainstream press had to fit into the new social order established, so that several printed media began to promote the government's actions in exchange for privileges, establishing an exchange of favours between the power of the press and political power (KUSHNIR, 2004).

14The year 1968 was marked worldwide by youth and student revolts, in which students organised themselves in various countries in demonstrations against the oppression existing in each social reality, distinct in each nation. From May 1968 in Paris, when an important juvenile demonstration took place against capitalism, consumption and alienation present in society, the rebellion of young people branched out in various parts of the world, through various ideologies and rejection of bourgeois conservatism in contestation of a political, existential and psychological order. "The United States experienced in 1968 a student revolt as intense as the French: refusal to go to war in Vietnam, refusal of the consumer society [...] Even Japan suffered a radical student protest, with a kind of 'university militia' clashing with police protected with helmets, bombs and shields. In Spain, the Franco dictatorship (of General Francisco Franco) was being confronted; in Italy, the authoritarianism of the university and the commodified culture were being fought. In all the demonstrations there were people killed, wounded and many beaten. Peace and love then turned into violence. In the decline of the movement, a minority became even more radical, falling into the clandestine terrorist action, such as the Baader-Meinhof in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, the Black Panthers in the United States, and other extremist (radical) organizations that were only dismantled in the 70s and 80s" (CARMO, 2010, p.76-77).

Received: July 15, 2021; Accepted: October 18, 2021

texto en

texto en